Abstract

Hiring subsidies are among the most widely used policies to support employment growth for certain groups of workers or disadvantaged geographic areas. In this article, we analyze the medium-run consequences of a generous, non-targeted permanent hiring subsidy implemented throughout Italy in 2015, which was widely used by firms. The results indicate that firms benefiting from the subsidy increased in size. However, compared to other firms, the growth rate of capital–labour ratio and value added per worker were lower after the subsidy. We conclude that policies to stimulate hiring must be accompanied by other interventions to support capital accumulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The non-restricted data are available from the authors.

Notes

It would be interesting to check if and how the estimated effects change over a longer horizon. However, the Covid-19 pandemic might have changed the data generating process. For this reason, we did not attempt to include years between 2020 and 2022.

Available for the period 2010–2018 thanks to a research project with ANPAL, the Italian agency for active employment policies.

By merging INPS with CO we lose about 28% of the INPS firms. The two dataset do not fully overlap because of the administrative nature of the two samples. For instance in INPS two firms of the same parent group (with different fiscal identifiers) are recorded as a unique firm if one of the two firms pays social security contributions also for the other company. They instead are separately recorded in CO.

The subsidy was introduced also to foster the adoption of a new type of permanent contract characterised by lower firing costs for firms with at least 15 employees (introduced in March 2015 by the so-called Jobs Act reform). See Sestito and Viviano (2018) for an evaluation of the overall impact of the hiring subsidy and the Jobs Act.

We experimented other cutoff dates, reaching the same results.

Results are qualitatively similar if we apply weights based on wages.

On the contrary, our choice implies that the analysis considers only continuing firms from 2013 or before. Firms starting after the introduction of the policy need to hire individuals, by definition. This would mechanically increase the hiring rate. Therefore, their hiring would not be the effect of the policy alone. For this reason, we exclude these firms from the sample. Similar considerations, in the opposite direction, hold for firms exiting the market after the policy.

One approach to purge from the higher propensity to hire on a permanent basis in 2011 and 2012 is to deflate the estimated effect of 2015 by 0.1, i.e. the size of the coefficients in 2011 and 2012 (Conley et al. 2012). Given the small size of the coefficients, the results do not change.

References

Abadie A, Athey S, Imbens GW, Wooldridge JM (2022) When should you adjust standard errors for clustering? Q J Econ 24003:1–71

Adamopoulou E, De Philippis M, Sette E, Viviano E (2021) The long-term earnings’ effects of a credit market disruption. Bank of Italy, Mimeo

Boeri T, Garibaldi P (2019) A tale of comprehensive labor market reforms: evidence from the Italian Jobs Act. Labour Econ 59(1):33–48

Boeri T, Ichino A, Moretti E, Posch J (2021) Wage equalization and regional misallocation: evidence from Italian and German provinces. J Eur Econ Assoc 19(6):3249–3292. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvab019

Brown A (2015) Can hiring subsidies benefit the unemployed? IZA World of Labor

Cahuc P, Carcillo S, Le Barbanchon T (2019) The effectiveness of hiring credits. Rev Econ Stud 86(2):593–626

Ciani E, de Blasio G (2015) Getting stable: an evaluation of the incentives for permanent contracts in Italy. IZA J Eur Labor Stud. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40174-015-0030-5

Ciani E, Grompone A, Olivieri E (2019) Long-term unemployment and subsidies for permanent employment. Temi di discussione (Economic working papers) 1249, Bank of Italy, Economic Research and International Relations Area

Conley TG, Hansen C, Rossi PE (2012) Plausibly exogenous. Rev Econ Stat 94(1):260–272

Daruich D, Addario SD, Saggio R (2022) The effects of partial employment protection reforms: evidence from Italy. Temi di discussione (Economic working papers) 1390, Bank of Italy

Desiere S, Cockx B (2022) How effective are hiring subsidies in reducing long-term unemployment among prime-aged jobseekers? Evidence from Belgium. IZA J Labor Policy 12(1). https://doi.org/10.2478/izajolp-2022-0003

Garibaldi P, Taddei F (2013) Italy: a dual labour market in transition. Country case studies on labour market segmentation, Technical report

Heckman JJ (1979) Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica 47(1):153–161

Imbens GW (2015) Matching methods in practice: three examples. J Human Resour 50(2):373–419

Lazear EP (2009) Firm specific human capital: a skill weights approach. J Political Econ 117(5):914–940

Neumark D (2013) Spurring job creation in response to severe recessions: reconsidering hiring credits. J Policy Anal Manag 32(1):142–171

Pasquini A, Centra M, Pellegrini G (2019) Fighting long-term unemployment: do we have the whole picture? Labour Econ 61:101764

Rubolino E (2022) Taxing the gender gap: labor market effects of a payroll tax cut for women in Italy. CESifo Working Paper Series 9671, CESifo

Saez E, Schoefer B, Seim D (2019) Payroll taxes, firm behavior, and rent sharing: evidence from a young workers’ tax cut in Sweden. Am Econ Rev 109(5):1717–1763

Saez E, Schoefer B, Seim D (2021) Hysteresis from employer subsidies. J Public Econ 200:104459

Santoro S, Viviano E (2021) Optimal trend inflation, misallocation and the pass-through of labour costs to prices. Mimeo, Bank of Italy, Economic Research and International Relations Area

Sestito P, Viviano E (2018) Firing costs and firm hiring: evidence from an Italian reform. Econ Policy 33(93):101–130

Vella F (1998) Estimating models with sample selection bias: a survey. J Human Resour 33(1):127–169

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose. We would like to thank the Guest Editor, Roberto Torrini, and the reviewer for the constructive comments. We also thank Antonio Accetturo, Giuseppe Albanese, and the seminar participants at the Bank of Italy. Replication files and additional results will be available at the webpage: http://sites.google.com/site/domdepalo/. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not imply any responsibility of the Bank of Italy.

Appendix

Appendix

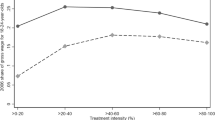

Hiring rate as a function of IV (sum of hires and conversions divided by firm size in 2013)—excluding the zeros. Note: Interactions of IV with year dummies. Vertical bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Standard errors clustered at the firm level. Additional controls: firm and year fixed effects

Hiring rate as a function of IV (sum of hires and conversions divided by firm size in 2013)—IV at the 50th percentile. Note: Interactions of IV with year dummies. Vertical bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Standard errors clustered at the firm level. Additional controls: firm and year fixed effects

Hiring rate as a function of IV (sum of hires and conversions divided by firm size in 2013)—IV at the 90th percentile. Note: Interactions of IV with year dummies. Vertical bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Standard errors clustered at the firm level. Additional controls: firm and year fixed effects

Share of hiring rates of the permanent vs temporary workers as a function of IV (sum of hires and conversions divided by firm size in 2013). Note: Interactions of IV with year dummies. Vertical bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Standard errors clustered at the firm level. Additional controls: firm and year fixed effects

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Depalo, D., Viviano, E. Hiring Subsidies and Firm Growth: Some New Evidence from Italy. Ital Econ J (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-023-00261-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-023-00261-3