Abstract

This paper exploits several reforms of wage subsidies in the framework of the German Minijob program to investigate substitution and complementarity relationships between subsidized and non-subsidized labor demand. We apply an instrumental variables approach and use administrative data on German establishments for the period 1999–2014. Particularly in small establishments (0–9 employees), subsidized Minijob employment comprises large shares of the work force, on average over 40%. For these establishments, robust evidence shows that increasing the subsidization of Minijob employment crowds out non-subsidized employment. Our results imply that Minijob employment in 2014 may have eliminated more than 0.5 million unsubsidized employment relationships just in small establishments. This represents an unintended and harmful consequence of the Minijob subsidy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

One in six German workers takes advantage of subsidized “Minijob” employment (BA (Bundesagentur für Arbeit) 2017). Introduced decades ago, the original purpose of the payroll tax subsidy was to reduce bureaucratic burden and to facilitate flexible minor employment relationships. At the same time, however, subsidized employment might crowd out demand for unsubsidized labor. With more than 7.4 million Minijob employment relationships (as of July 2017), their impact on unsubsidized employment could potentially be substantial. Even though subsidized employment relationships exist in many national labor markets, the relationship between subsidized and unsubsidized employment and the potential crowding out and displacement effects, surprisingly, have hardly been investigated, so far. This study exploits various reforms of subsidized employment to identify the causal effect of payroll tax subsidies on the demand for unsubsidized labor.

Minijobs (geringfügige Beschäftigung) are employment relationships which yield less than a given amount of monthly earnings, currently 450 Euro; this corresponds to about 13% of gross average monthly earnings in unsubsidized employment.Footnote 1 Small establishments and the retail, general service, and restaurant sector use Minijob employment most intensely. More than 60% of Minijob employees are female. The age distribution of Minijobbers peaks below 20 (pupils, students), at 40–50 (often housewives), and above 60 (retirees). One in ten Minijobs is held by an unemployed person (Körner and Meinken 2013; Hohendanner and Stegmaier 2012). The subsidy aims at offering them a stepping stone to return to the labor market. Similar to other active labor market policies, the effectiveness of Minijobs has been evaluated with mixed results (Böheim and Weber 2011; Freier and Steiner 2008; Caliendo et al. 2016). Similar programs exist in Austria and Switzerland.

Unsubsidized employment involves social insurance contributions of about 20% for employer and employee each and income tax obligations of employees. In contrast, Minijob employment is exempt from both employee social insurance contributions and income taxes. Instead, employers pay a fixed share (contribution rate) of Minijob earnings to cover, both, social insurance contributions and income taxes. This contribution rate changed in discrete steps from 22% in 1999 to 30% since 2006. We use these increases in the price of Minijobs for employers, i.e., the declines in subsidization to identify the causal effect of Minijob employment on the demand for unsubsidized labor.Footnote 2

Our study connects to two different lines in the international literature, one discussing displacement effects of active labor market policies and the second discussing the employment effects of payroll taxes and payroll tax subsidies.

In their meta analyses, Card et al. (2010, 2018) pointed out that the impact of active labor market policies (ALMP) on those that do not participate is an important unsettled question and that the relevant literature is scarce. In an earlier contribution, Dahlberg and Forslund (2005) find large displacement effects of Swedish ALMP in particular of subsidized employment. More recently, Crépon et al. (2013) used randomized experiments to determine displacement effects of ALMP in France. They conclude that standard program evaluation would overstate the programs’ effects by not considering the displacement effects.

In the literature on employment effects of payroll taxes, most studies find no employment effects in response to changes in effective payroll taxes. Saez et al. (2019, p.1) argue that payroll tax incidence falls on workers’ net wages as “received wisdom.” In an early study, Gruber (1997) shows that the reduction of payroll taxes levied on Chilean firms from 30 to 8.5% did not affect employment. Instead, it benefited workers via higher wages. Similarly, Anderson and Meyer (2000) evaluate the introduction of experience rating for firms’ unemployment insurance contributions in the state of Washington and find no employment effects of changes in payroll taxes. This confirms earlier findings by Anderson and Meyer (1997). Likewise, Korkeamäki and Uusitalo (2009) do not find statistically significant employment responses to regional reductions in payroll taxes in northern Finland. They conclude that wage increases took up a large share of the potential cost reductions. The same holds for a regional payroll tax reduction in northern Sweden analyzed by Bennmarker et al. (2009). Even though they consider a change in tax rates twice as large as that used in the Finnish study, these authors find solely an increase in firm entry but no employment change for existing firms. Again, employees benefited from wage increases. Huttunen et al. (2013) focus on a payroll tax subsidy in Finland that targeted low skill older workers. The authors do not find a response in the target group’s employment rate. Generally, the lack of employment effects might be explained by wage adjustments in combination with inelastic labor supply or demand (for a discussion see also Hamermesh 1993Footnote 3).

A few contributions do document employment responses to payroll tax subsidies. For example, Kangasharju (2007) investigates a Finnish subsidy which supports firms that hired previously unemployed workers. Based on panel data, the author concludes that employment increased in subsidized firms without effects on the region or competing firms. Garsaa and Levratto (2015) study the effects of reductions in social security contributions on employment growth in French manufacturing firms and also find the expected effects. In both, the Finnish and the French case, the positive employment effect is found for large and successful firms. If such establishments benefit from (short-run) subsidies and differ in their technology from other firms, it is worthwhile to pay attention to effect heterogeneities.Footnote 4 Most recently, Saez et al. (2019) found that a major reduction in payroll taxes for the employment of younger workers in Sweden did not affect wages but increased employment. As this result contradicts most of the literature, the authors argue that it may be related to the impact of fairness norms within firms which render wage discrimination impossible.

We contribute to the literature in several respects: first, we exploit exogenous changes in federal subsidies and apply an instrumental variables approach to identify the causal effects of subsidized employment on non-subsidized employment (i.e., a potential substitution versus complementarity). In particular, our first-stage exploits increases in social security contributions levied on employers for Minijob employment, which should decrease the demand for Minijob workers because they become more expensive. At the same time, the cost of non-subsidized workers remains constant, so that any changes in unsubsidized employment are solely due to the lower demand for Minijobbers. This identification strategy allows us to determine the adjustment in unsubsidized employment in “complier” establishments, i.e., those adjusting their employment in response to changes in subsidization. Compared to, e.g., a difference in differences strategy, our instrumental variables approach explicitly accounts for other policy changes that would otherwise be challenging to control for. As the reforms changed the relative costs of different types of labor input, we address the question of whether the price change for one input generates substitution or complementarity effects at the establishment level.Footnote 5

Second, in contrast to wage subsidies evaluated in the previous literature, the Minijob subsidy is not tied to worker (e.g., age or skill level) or job characteristics (e.g., region or industry). Instead, the subsidy is universally available for all individuals. This renders the subsidy effects independent of specific characteristics of the work force, industry, or region and enhances the external validity of the findings. Third, we consider fixed effects estimation to account for establishment specific time-constant unobservables reflecting, e.g., industry, region, management characteristics, firm-age, or the permanent features of the workforce.

Fourth, we extend prior research that commonly considers labor supply as a homogeneous input and evaluates the effects on total overall employment. Instead, we focus on the impact of changes in subsidized Minijob employment on unsubsidized full-time and part-time employment and apprenticeship positions. From a theoretical perspective, heterogeneous labor inputs to a production function may be complements (e.g., in a high skill–low skill setting) or substitutes (e.g., in a setting where low skill services can be provided by apprentices, part-time workers, and Minijob employees). It is an empirical question, which of the input relationships dominates. So far, potential substitution and complementarity effects between subsidized and unsubsidized labor have not been addressed in the literature on employment effects of wage subsidies. Instead, the literature on heterogeneous labor demand looks at the wage effects on employment using industry-level data.Footnote 6 Our instrumental variables strategy expands on these contributions and studies employment effects with recent data and at the establishment level. This evidence on the crowding out and displacement of unsubsidized employment is of international interest both at the macro- and the micro-level.

We find that the statutory reductions of Minijob subsidization (i.e., increases of employer contribution rates) substantially reduce demand for Minijob employment in small establishments (0–9 employees), which use Minijob employment most intensely. Our findings suggest that unsubsidized employment and subsidized Minijob employment are substitutes in small establishments, i.e., unsubsidized employment increases if Minijob employment declines. The substitution effects seem plausible given that small businesses are mainly service providers and need workers for low skill retail, in restaurants, or delivery and logistics. These tasks can be and are typically performed by different types of employees, i.e., apprentices, low skill part-time workers, or Minijobbers. More specifically, our results suggest that one additional Minijob substitutes about 0.5 unsubsidized jobs. Neglecting general equilibrium effects, this implies that Minijob employment in 2014 and just in the small establishment sector crowded out more than 0.5 million unsubsidized employment relationships. Our results hold up in numerous robustness checks. We also demonstrate that our instrument is plausibly exogenous and the findings are not sensitive to a relaxation of the exclusion restriction by using the approach of Conley et al. (2012). In sum, the crowding out effect of Minijob on regular, unsubsidized employment represents an unintended consequence of the program, which deserves attention.

In the next section, we describe the institutional background and the reforms that we exploit in our analyses. We discuss our empirical approach and describe our data in Section 3. In Section 4, we present our results and robustness tests and Section 5 concludes.

2 Institutional background

The Minijob program is one of the largest labor market programs in Germany. As of 2017, nearly 7.5 million individuals, i.e., one-sixth of the labor force took advantage of this indirect wage subsidy (BA (Bundesagentur für Arbeit) 2017). Legally, individuals performing Minijobs are part-time employees subject to general labor laws. They benefit from sick pay, maternity leave benefits, employment protection, and are entitled to paid vacation days. At the same time, the Minijob program stipulates that individuals working in minor employment relationships are exempt from otherwise mandatory contributions to social insurances and from income taxes. Instead, employers pay a fixed share of a worker’s gross earnings to social insurance and tax authorities. The subsidy is currently available if monthly earnings do not exceed 450 Euro. Labor earnings above that amount are taxable and subject to social insurance contributions by workers and employers (for details see, e.g., Eichhorst et al. 2012; Berthold and Coban 2013). Generally, all Minijobbers avoid social insurance contributions, which amount to about 20% of gross earnings. Nevertheless, the total value of the subsidy varies across individuals because the exemption from income taxes depends on individual circumstances and varies with marginal tax rates that—as of 2007—ranged between 15 and 45%. The overall subsidy for individual workers may well add up to about 40% of gross earnings as long as the earnings limit is not exceeded. While the benefits from the subsidies for individual workers remained constant over time, other elements of the program underwent numerous reforms.

This type of subsidy existed since 1911 (Reichsversicherungsordnung). Over time, the rules were modified with varying objectives, e.g., to reduce bureaucratic burden, to incentivize labor supply, to raise social insurance contributions, or to provide incentives for unsubsidized part-time employment. The changes in rule always affected both incumbent and newly hired workers. In 1999, a reform fixed the upper earnings limit of Minijob employment at 325 Euro and set a limit of at most 15 working hours per week. Employees were exempt from social insurance contributions and income taxes, but employers paid lump-sum contributions of 22% of earnings, which in part contributed to the pension insurance and in part to the health insurance (see Table 1).

A subsequent reform in 2003 aimed at reducing illicit employment and increasing employment opportunities for the unemployed through Minijobs as a stepping stone to the unsubsidized labor market.Footnote 7 The reform also intended to enhance firms’ flexibility and to reduce labor costs. For that purpose, it abolished the limit of 15 working hours per week, allowed to add a Minijob on top of an unsubsidized employment contract (“add-on Minijob”), raised the monthly earnings limit to 400 Euro, and fixed the employer contributions at 25% up from previously 22%.Footnote 8 After this increase in contributions, a small share was channeled to the federal budget in addition to the social insurances that already benefited before the reform. In 2006, employers’ contributions to social insurances and the federal budget rose to 30% and in 2013, the monthly earnings limit increased to 450 Euro.Footnote 9 Table 1 summarizes the relevant institutional changes of the Minijob program between 1999 and 2013. The table also reveals that all reform laws were passed shortly prior to the implementation dates, leaving little room for anticipation. Furthermore, employment adjustments (hiring and layoffs) usually take time and our outcomes are measured annually per June 30, so that it is virtually impossible that our data encompass any anticipatory effects.

In addition to employer contributions for social insurance and income tax obligations of Minijob employment, there exist three expense sharing schemes of lower salience: employers have to share the costs of sick pay (U1), maternity benefits (U2), and insolvency benefits (U3). These schemes exist since 2003 and demand small gross earnings shares between 0.1 (2005–2008) and 1.45 (2015) percent (for details see MZ (Minijob-Zentrale) 2018 and Appendix Table A.3). We disregard expenditures on these schemes in our main analyses and perform robustness tests to evaluate whether our results are sensitive to considering these additional costs.

Due to data availability, our identification strategy exploits contribution rate reforms as of April 1, 2003 and of July 1, 2006. It is important to pay attention to other potential changes in the institutional setting in this period. In 2003, two parallel changes occurred with respect to Minijob employment: the abolition of the hours limit and the introduction of add-on Minijobs. We explicitly control for these specific measures in our empirical model.

Overall, the Minijob reforms were introduced within an extensive package of labor market reforms (Hartz reform) in the early 2000s. The Hartz reform was implemented in four steps: Hartz I and II were passed in December of 2002 and mostly became effective on January 1, 2003. Hartz I deregulated temporary agency employment and introduced vouchers for vocational training. Hartz II modified marginal employment and introduced subsidies for the self-employment of previously unemployed workers. Hartz III and IV were passed in December of 2003. Hartz III (effective January 1, 2004) restructured the unemployment insurance itself. Finally, Hartz IV (effective January 1, 2005) reformed unemployment benefits and their interaction with means-tested social assistance.Footnote 10

It appears plausible that many of the reforms, which occurred at different points in time, are orthogonal to the demand for subsidized Minijob employment (e.g., the internal organization of the unemployment insurance, the introduction of training vouchers, or changes in means-tested benefits). Of particular interests are reforms that might interact with the demand for Minijob employment such as the support of temporary agency work and subsidies of self-employment. Because within a given firm, the use of temporary agency workers or self-employed workers might crowd out unsubsidized employment. If this reduced unsubsidized employment, both institutional changes would downward bias the estimates of the substitution effects of Minijob employment, which became more expensive after its reforms. Overall, the institutional framework should not invalidate our analyses: for most changes, we do not expect direct effects on firms’ production technology and the within-firm relationships between subsidized and unsubsidized employment. Those reforms that may affect labor demand should generate a conservative, downward bias in the expected substitution relationship between Minijobs and unsubsidized employment. Separately, some studies argue that the Hartz IV reform may have reduced the reservation wages of low skill workers and thus affected labor supply (e.g., Burda and Seele 2016). If low skill workers predominantly work in Minijobs, we would again obtain a downward bias in our estimates since rising Minijob contributions may be balanced by lower wage bills. We continue the discussion of identifying assumptions in the next section.

The utilization of Minijob employment is described by Hohendanner and Stegmaier (2012) or Bachmann et al. (2017). Recently, out of 7.4 million Minijobs, about 2.6 million are “add-on Minijobs” leaving 4.8 million subsidized, exclusively Minijob employment relationships. Figure 1 shows a slight positive trend in Minijob employment since 2004 that appears to be driven by add-on Minijobs. After the 2003 reform, which abolished the weekly hours limit and allowed add-on Minijobs, the share of add-on Minijobs increased from about 17% in 2003 to above 30% in 2016.Footnote 11 We directly control for these changes in our empirical model.

Total, regular, and add-on Minijob employment (Q1.2000–Q4.2016). Minijob employment covers those employed in “450 Euro” Jobs (excluding short-term employment relationships). Regular Minijob employment counts employment relationships where the individual works only on the Minijob without an additional employment relationship registered at the same time. Since 2003, add-on Minijob are possible; here, Minijob employment is held in addition to other registered employment. The total number of the omitted short-term employment relationships never exceeded 350.000, in Dec. 2016 below 185.000. Source: Data received via personal email from Statistik der Bundesagentur für Arbeit

3 Methods and data

3.1 Empirical strategy

We exploit recent legislative changes to identify the causal effect of the Minijob subsidy on employers’ demand for alternative non-subsidized types of employment. Specifically, we focus on the following outcome equation:

where yit represents the unsubsidized employment of establishment i in year t. We consider various outcome measures: the number of employed individuals, the number of hours worked, and their respective logarithmic values. The vector β0i includes establishment fixed effects, which account for, e.g., industry, region, or firm characteristics such as year of establishment, management characteristics, or permanent features of the workforce. The explanatory variable of interest Miniit measures the incidence of Minijob employment in establishment i in year t. Depending on the outcome measure (y), we use a corresponding specification for Miniit such as the number of individuals, number of hours worked, or their logarithmic values. The polynomial f(trend) flexibly captures the time trend and Xit controls for potentially time-varying (institutional) characteristics. γ, β1, and β2 are the parameters to be estimated, and εit is an error term. We expect a negative estimate for γ if Minijobs substitute unsubsidized employment and a positive one if Minijobbs and unsubsidized employments are complements.

Given the potential endogeneity of Minijob employment, which managers chose simultaneously with unsubsidized employment, we apply an instrumental variable (IV) approach: we use the shifts in contribution rates occurring in reform years 2003 and 2006 as an instrument for Miniit. This identifies the local average treatment effect (LATE) for those establishments responding to an increase in costs of Minijob employment, i.e., the compliers, and permits a clear interpretation of the mechanism driving the response. The corresponding first-stage equation is:

where Contributiont is the employer contribution rate for Minijobs in year t. Again, the parameters δ, α1, and α2 are to be estimated within a fixed effects framework and ϵit is an error term.Footnote 12 To account for the potentially confounding effects of simultaneous law changes, we additionally control for the statutory limits on monthly earnings and working hours in Minijob employment in both equations (cf. Table 1).Footnote 13

The internal validity of our IV approach rests on the assumptions that the instrument is relevant and exogenous, and that its effects are monotonous. The relevance condition requires that changes in contribution rates affect employers’ demand for Minijob employment. We test this condition and discuss the results in Section 4. The exogeneity condition requires that changes in contribution rates have no direct impact on demand for unsubsidized employment. This condition cannot be tested; however, we assume that conditional on Minijob employment the demand for unsubsidized employment does not vary independently with the cost of Minijobs, i.e., that any response in unsubsidized employment to changes in contribution rates occurs in connection with adjustments in Minijob employment. This exogeneity condition is met if employers first determine demand for subsidized labor and then adjust demand for unsubsidized labor. The exogeneity condition also requires that the shift in the contribution rate itself is unrelated to labor demand structures. Such a correlation is implausible as the reforms were politically motivated, followed very different rationales over time, and affected the entire national labor market and all establishments. Nevertheless, in our baseline specification, we define trend as a third order polynomial in calendar years to flexibly control for any time trends in unsubsidized labor demand. In addition, we parametrically control for other changes occurring in 2003 and offer a robustness test of the exogeneity assumption following Conley et al. (2012). Finally, the monotonicity condition assumes that there are no defiers, i.e., establishments that increase Minijob employment in response to its cost increases.

3.2 Data

We use administrative data from the Establishment History Panel (BHP) provided by the Research Data Centre of the German Federal Employment Agency at the Institute for Employment Research (IAB). The data use the population of establishments in Germany with at least one employee subject to social security or in Minijob employment as of 30 June of any given year between 1975 and 2014 (Schmucker et al. 2016). The BHP provides a random 50% sample of these establishments, which comprises between 1.3 and 2.9 million establishments per year. The sample design implies that newly entering and exiting establishments are also included. Besides a large sample size, the BHP offers precise longitudinal information on stocks and flows of different types of employees. We focus on the period 1999–2014 during which the data provide information on Minijob employment.

In our sample, we drop observations on private households offering Minijob employment, which corresponds to approximately 6% of all employers. We use more than 3 million different establishments. Our sample comprises 20,241,824 establishment-year observations for the period 1999–2014. Approximately 79/19/2% of establishment-year observations are in the small (0–9), middle (10–99), and large (100+ employees) establishment size categories, which are defined based on the number of employed individuals (head count) including unsubsidized and Minijob employment. On average, we observe 9.7 unsubsidized and 2.3 Minijob employees per establishment and year.Footnote 14 Minijob employees are unequally distributed across establishment sizes with the highest Minijob employment share in the group of small establishments.Footnote 15

Our dependent variable is an establishment’s unsubsidized employment measured as the number of individuals or the total daily number of hours worked by these employees. Unsubsidized employment combines full-time and part-time workers as well as apprenticeship positions. We consider the head count and the number of hours worked because both dimensions are of interest in their own right: the first describes the number of affected individuals and the latter permits conclusions with respect to the volume of hours worked, e.g., an interpretation of full-time equivalents.Footnote 16

Similarly, our key explanatory variable measures an establishment’s Minijob employment in terms of the number of workers or hours worked per day. As the BHP lacks information on working hours, we draw on survey data from the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP), which is a longitudinal survey of over 11,000 private households conducted annually since 1984 (Wagner et al. 2007). The SOEP asks respondents detailed questions on labor market participation including the usual number of working hours per week and the type of employment. We use this information with cross-sectional weights to calculate annual averages of daily working hours by employment type (see Appendix Table A.1). To assure comparability with the BHP, we exclude employees in private households and those not being subject to social security contributions (civil servants and self-employed) from the SOEP when calculating the annual means. Appendix Table A.1 reveals that average daily working hours remained relatively constant over time with nearly 9 h in full-time, 5 h in part-time, and around 2.5 h in Minijob employment. Given that apprentices spend some of their time in school, we use average part-time employment hours to approximate the labor input of this group. We then combine the annual averages with BHP data to calculate the volume of hours worked in unsubsidized and Minijob employment: for each establishment, we multiply its number of employees in a given employment type by the respective average working time in a particular year as gathered from Appendix Table A.1.Footnote 17 We acknowledge that our measure of working hours is relatively crude. Nevertheless, its value added is that we can interpret the estimates in terms of full-time equivalents instead of just studying the number of employed individuals at the extensive margin.

Figures 2 and 3 describe the share of employees in Minijobs and share of hours worked by Minijob employees over time and by establishment size. Both figures show the uptake in Minijob employment around the 2003 reform and suggest a small decline after the 2006 reform. In addition, we see vast differences in the relevance of subsidized Minijob employment across establishment sizes. In small establishments, on average, two in five employees are on Minijobs and Minijob employees account for almost 20% of the hours worked. If small firms predominantly sell individualized services as opposed to running larger operations as in manufacturing companies, this may explain their enhanced need for flexible employment structures and thus Minijob employment.

To provide internally valid analyses, we focus on small establishments with between 0 and 9 employees. Figures 2 and 3 show vast differences in employment patterns across establishment sizes. Unfortunately, we cannot exploit the potential heterogeneities in how firms respond to changes in the subsidy along the firm size distribution in more detail because the first-stage IV-regressions do not confirm the relevance of the instrument in the sample of large establishments (results not presented).Footnote 18 Our subsample of small establishments yields a strong first stage, as we show in the next section, and accounts for most observations providing 16.1 of overall 20.4 million establishment-year observations on about 2.6 million different establishments.Footnote 19,Footnote 20

Our instrument corresponds to the sum of statutory contributions for Minijob employment paid by the employer (see last column of Table 1) and is expressed in percent of gross earnings. As our outcomes are measured per June 30 of each year, we also consider the contributions as of this date. The second reform per July 1, 2006 thus might only affect the outcomes measured in 2007 and later.Footnote 21

Further, we construct a dummy variable that indicates the period before April 1, 2003 to reflect the working hour limit of 15 h. Another institutional variable is the monthly earnings limit for Minijobs measured in Euro and the average social insurance contribution rate paid for unsubsidized employees (DRV (Deutsche Rentenversicherung Bund) 2016a). Table 2 shows descriptive statistics for the dependent and independent variables in our sample.

4 Results

4.1 Baseline results

Table 3 presents the fixed effects estimation results for our main sample. Each column represents a different dependent variable describing the number of individuals in unsubsidized employment, its log value, the number of daily hours worked by unsubsidized workers, and its log value. Row 1 presents the estimate of γ without accounting for the potential endogeneity of labor demand shifts, whereas row 2 shows the IV estimate. For the first stage, we show the estimated coefficient δ from Eq. 2 in row 3. Row 4 displays the corresponding reduced-form effects of the instrument on the outcomes.

The linear regression estimates of Eq. (1) in row 1 yield that Minijob employment is significantly and negatively correlated with unsubsidized employment in small establishments. The first-stage estimates of δ in row 3 as well as the F test statistics presented in the bottom row of Table 3 confirm that the instrument is relevant as the values of the F-statistics are far beyond the critical values: as expected, higher contribution rates are negatively correlated with Minijob employment despite the generally increasing trend (see Figs. 2 and 3).

The key results of interest are the 2SLS estimates of the causal effect of Minijob on unsubsidized employment presented in row 2 of Table 3. For all four outcomes, the point estimates are negative and highly statistically significant. This suggests that in small establishments, an increase in Minijob employment (due to reduced contribution rates) substitutes unsubsidized employment, i.e., the sum of full-time, part-time, and apprenticeship employment. The patterns are similar across all dependent variables and indicate that each Minijob employee and each hour worked by a Minijob worker substitutes about half an unsubsidized employee (column 1) and half an hour worked by an unsubsidized employee (column 3). Accordingly, based on our specification, on average, two Minijob workers replace one non-subsidized employee. The coefficient estimates in columns 2 and 4 suggest that the number of unsubsidized employees and their hours worked decline by about 0.35% if the respective Minijob employment increases by 1%. The similarity in effect sizes for the head count and hours outcomes is surprising and most likely due to the skewed outcome distributionFootnote 22: about 40% of the firms in our sample have zero full-time employees, 70% have zero part-time employees, and almost 90% have no apprentices (for the distribution see Appendix Table A.4). As the causal effect estimates are estimated in this discontinuous setting, we prefer to avoid a cardinal interpretation and instead focus on sign and precision of the estimates.

We derive these IV estimates assuming that the legislative changes in the Minijob contribution rates do not have direct effects on the employers’ hiring behavior with respect to unsubsidized workers (except via the demand for Minijob employment). Specifically, this exclusion restriction assumes that in

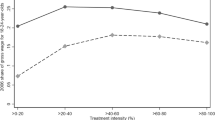

π is valued zero. The methods developed by Conley et al. (2012) allow us to test the sensitivity of our results to violations of this exogeneity assumption. For this purpose, we estimate the second stage coefficient (γ) and its confidence interval if the exclusion restriction is not exactly valid and π deviates from zero (for prior applications see, e.g., Wang 2013, Dimico 2017, Ager et al. 2018, or Nybom 2017). We apply the “union of confidence intervals” approach and assume that the coefficient of the instrument (π) in Eq. (3) is drawn from an asymmetric, positive support. The four panels in Fig. 4 depict the coefficient estimate of interest (γ) and its 95% confidence interval depending on the value of π, which under the exclusion restriction is zero. The x-axes depict π as a share of the reduced form estimate of the contribution rate (see row 4 of Table 3). All four panels of Fig. 4 show that the estimates of γ remain statistically significant until π reaches about 80 or 90% of the reduced form estimate. Thus, a potential omitted variable in our second stage regression, which is correlated with the contribution rate, would have to account for about 80% of the reduced form effect to render the 2SLS estimate insignificant, which is unlikely. Therefore, our main conclusions hold even if we relax the exogeneity assumption.

Sensitivity of the IV estimates of the Minijob effect (γ) to violations of the exclusion restriction for four outcomes. The bold line represents the 2-SLS estimate of the Minijob effect (i.e., coefficient γ in Eq. 1); the dashed lines show the boundaries of its 95% confidence intervals. The “Bias relative to the reduced-form estimate” on the x-axis reflects the deviation of the value of the instrument’s coefficient in the second stage regression as a fraction of the reduced form coefficient estimate (see row 4 of Table 3). At 0% bias, the estimate of the Minijob effect corresponds to row 2 of Table 3. The confidence intervals were determined following the “union of confidence intervals” approach as introduced by Conley et al. (2012). Source: BHP (1999–2014)

4.2 Robustness tests

In order to gauge the reliability of our results, we offer a broad set of robustness checks and describe the heterogeneity of effects. Specifically, we consider (i) changes in the specification of the time trend, (ii) changes in the definition of dependent variables and the instrument, (iii) heterogeneity checks, and (iv) changes in the sample composition.Footnote 23 Table 4 shows the alternative 2SLS results. For comparability, the first row repeats our baseline 2SLS estimates (see Table 3, row 2).

-

(i)

Our data cover the period 1999–2014 on an annual basis. With such a relatively short period, estimation results might be sensitive to the representation of the time trend. As a robustness check, we use second- or fourth-order polynomials of the time trend instead of the third-order polynomial in our baseline specification. The results in rows 1 and 2 confirm prior findings. The estimated causal effects remain very close to the baseline values and confirm significant substitution effects.Footnote 24 In order to capture potentially different time trends across various industries and regions, we also provide alternative specifications which interact the cubic time trend with industry indicators (see row 3) and federal state indicators (see row 4). The estimation results are robust to these additional controls.

-

(ii)

Next, we modify the dependent variables in two ways. First, we omit the group of apprentices from the count of unsubsidized workers because their development might be affected by alternative trends such as demographic shifts and changes in the educational system. Row 5 presents estimation results without this group. The effects are similar to those of the baseline estimation, with the exception of column 3 where the effect of Minijob employment increases in magnitude from − 0.559 to − 0.660. This might suggest that apprentice employment dampens the effect of adjustments in Minijob employment.

Second, we modify the definition of the logarithmic values. In our baseline estimations, we added a constant of 0.001 prior to taking logarithms in columns 2 and 4 in order to be able to include the establishments with zero outcome values. Given that the sample contains a large share of zero values for the dependent variables (25%), we investigate whether the choice of the added constant affects results. Row 6 in Table 4 shows the estimates for columns 2 and 4 when, we alternatively add a value of 0.1 prior to calculating the logarithms. The estimates change slightly, but the difference is moderate and overall, the results are robust.

Third, we modify our instrument. So far, we only considered the salient changes in contribution rates consisting of tax and social insurance contributions (see Table 1, last column). In addition, employers have to contribute to expense sharing systems (U1–U3). As these payments varied over time as well (see Table 7), we investigate whether our estimates change when these expenses are additionally included in the instrument.Footnote 25 The baseline results are generally robust to this modification though the 2SLS estimates in row 7 increase slightly for both head count outcomes and decrease for the hours outcomes compared to the baseline estimates. The results in columns 1 and 2 would suggest that employers do respond to the full cost and not just to the contribution rate considered so far; however, this interpretation is not confirmed by the results in columns 3 and 4.

-

iii

In row 8, we restrict the sample to the services sector only, which is the major user of the Minijobs employment. The sample size declines to 12.8 million observations. The effects are slightly smaller in magnitude than for the full sample, but overall the same patterns obtain.

-

iij

Next, we address sampling issues. First, we show estimation results after omitting the data gathered in the first periods after the two reforms were implemented. Given that the 2003 reform was implemented in April and employment adjustments usually take time, it is likely that the establishments did not yet (fully) react to the new set-up as of June 30, when the measurement is taken. In row 9, we show results after omitting data gathered in 2003. As the results hold up, we find no support for relevant postponement effects. In the second test, we omit data gathered in 2007 because this is the first period after the second reform was implemented. Not surprisingly, the estimates are now somewhat weaker (see row 10), but still underpin our main conclusions.

Second, 25% of the establishment-year observations in our sample do not have unsubsidized employees. In their vast majority, these establishments employ only Minijob workers. As these establishments may respond most strongly to changes in the cost of Minijob employment, we include them in our baseline sample. In order to test the sensitivity of our findings with respect to the composition of small establishments, we reestimate our models after omitting two groups of establishments from the sample. Specifically, we drop (i) establishments which had no unsubsidized employment over a period of three consecutive years and (ii) establishments which were observed only once or twice in the sample and at that time had no unsubsidized employment. The remaining 11.7 million observations have unsubsidized employment at least once, which reduces the share of observations with a zero valued outcome from 25 to 6% of the overall sample. Row 11 in Table 4 shows that our estimation results respond differently to this modification. The significant substitution effects are maintained throughout though with slightly increased effects in columns 1 and 3 (level outcomes) and reduced effects in columns 2 and 4 (log-value outcomes), both compared to the baseline. Nevertheless, this allows us to conclude that our main results are not entirely driven by establishments created only for the employment of Minijob workers.

Third, in row 12, we omit observations collected after 2010 as the last change in the value of the instrument occurred in 2006, this reform may not determine labor demand structures for as long as 8 years afterwards. The reduced sample of 12.0 million observations yields slightly attenuated point estimates, but still shows strong substitution effects.

Fourth, our sample considers all establishment-year observations with 0–9 employees. As the establishment size might be a response to the analyzed policy reforms, the sample composition might be endogenous. Therefore, in row 13, we consider only those firms which had 0–9 employees in at least one year between 1999 and 2002, i.e., prior to the 2003 reform. We lose one-quarter of the original sample but the point estimates continue to be significantly negative and in the same range.Footnote 26

Finally, we tested the sensitivity of our results to the definition of “small” establishments. In row 1, we widen the definition to establishments with up to 20 employees: the extended sample confirms the significant substitution effects.Footnote 27

5 Conclusions

We investigate the causal effect of subsidized employment on unsubsidized employment from a firm perspective. Minijobs in Germany are employment relationships with reduced payroll taxes. This implicit subsidy has been modified several times since 1999. Our identification strategy exploits these legal law changes as exogenous shocks to the cost of subsidized Minijob employment. Specifically, we apply an instrumental variables (IV) approach within a panel data framework. We use vast administrative establishment level data for the years 1999–2014, which covers a 50% random sample of all establishments registered with the unemployment insurance.

We carefully describe the utilization of subsidized Minijob employment by establishments. Currently, one in six employment relationships in the German labor market fall into this category (BA (Bundesagentur für Arbeit) 2017). We find that Minijob employment is predominantly used by small establishments, which make up about 80% of all establishments and fill up to 40% of their positions and about 18% of their hours of work by Minijobs employment. Thus, our main analysis focuses on small establishments.

Our first-stage estimates yield that the instrumental variable, i.e., the rate at which employers contribute to social insurance and income taxes for Minijob employment, significantly affects the demand for Minijob employment. The main IV results suggest that Minijob employment crowds out unsubsidized employment. We find this pattern of substitution for both the number of employees and of hours worked. Using their logarithmic transformations leads to similar conclusions. We demonstrate that our results are not driven by a specific sample selection, the definition of the outcomes and instrumental variables, and the considered time trend specifications. Our estimates are also robust with regard to deviations from the exclusion restrictions based on tests suggested by Conley et al. (2012). The effects are mainly identified for continuing firms and therefore, do not capture possible direct reform effects on firm entry or exit.

The estimated effect sizes imply that for small establishments, with currently about 1.2 million Minijob employment relationships, for every additional Minijob employment about 0.5 unsubsidized jobs are lost. Thus, already among small establishments, more than half a million unsubsidized employment relationships are crowded out by subsidized Minijobs. This represents a negative side effect or unintended consequence of a subsidy program, which was meant as a stepping stone into regular employment for the unemployed or those re-entering the labor market. It is important to note that there is also little support for the effectiveness of Minijobs in this intended role (cf. Freier and Steiner 2008; Caliendo et al. 2016).

In addition, the subsidy generates fiscal costs. Minijob employment generates average monthly earnings of 300 Euro (DRV 2016b). The difference between the employer contribution rate for Minijobs and the social insurance contribution rates for unsubsidized employed amounts to about 12 percentage points of gross earnings.Footnote 28 Thus, the social insurance subsidy for average Minijob employment amounts to 36 Euro per month and 432 Euro per year. With about 7 million Minijob employees, this adds up to 3.02 billion Euro per year. If two Minijobs were substituted by one unsubsidized full-time, part-time, or apprenticeship job, unsubsidized employment would generate higher earnings (see DRV (Deutsche Rentenversicherung Bund) 2016a) and would contribute to social insurances at higher rates. Social insurances were to gain substantially. Additionally, revenues from income tax payments would be collected from workers. One might argue that abolishing the subsidy would shift Minijob employment to the informal sector. However, this does not agree with our finding of a substitution relationship between Minijob and unsubsidized employment, which instead suggests that demand for unsubsidized employment increases if Minijob subsidies decline.

The analysis implicitly assumes that there are no substantial shifts in labor supply over the considered period; clearly, our interpretation that changes in employment reflect changes in labor demand strictly holds only to the extent that the nature and quantity of labor supply remained constant. The literature on causal employment effects of payroll tax subsidies generally maintains this assumption. With respect to the reform studied here, Caliendo and Wrohlich (2010) investigate the short-run labor supply responses to the 2003 Minijob reform; they find no significant effect on participation in marginal employment which corroborates our interpretation. Given that over time the payroll tax subsidies were reduced, it is not plausible to expect an increasing inflow from the shadow economy into marginal employment.

Our findings suggest that employers respond rationally and replace subsidized by unsubsidized employment if the cost of subsidized employment increases. This pattern matches the recent evidence on the impact of minimum wages in Germany introduced in 2015. With the introduction of binding minimum wages, Minijob employment became more costly for employers because it frequently relies on unexperienced low skill workers whose wages rose due to the minimum wage introduction. The existing analyses on the effects of German minimum wages indicate that demand for Minijob employment declined in response. About half of the related job losses were filled by unsubsidized employment (vom Berge et al. 2016, Caliendo et al. 2018). This confirms our finding of a substitution relationship between subsidized Minijob employment and unsubsidized regular employment. Despite the introduction of minimum wages, which rendered some Minijob employment less attractive, more than 7.4 million such jobs still exist and at least partly crowd out unsubsidized employment relationships.

Notes

STBA (2017, p.4) reports that gross average monthly earnings in unsubsidized full- and part-time employment amount to 3415 Euro as of March 2017. Minijobs additionally comprise short-term employment relationships (kurzfristige Beschäftigung), which do not extend beyond (currently) 70 days per year, independent of earnings. We disregard this second category of Minijob employment, which is less prevalent and follows a strong seasonal pattern: BA (Bundesagentur für Arbeit) (2010) reports between 270,000 employees in winter and about 450,000 in summer months. This compares to more than 7 million employment relationships under the 450 Euro limit.

Hamermesh (1993, p.169) shows that in a situation dominated by the low labor supply elasticity of adult male workers increases in payroll taxes should reduce wages. Increases in payroll tax subsidies should generate at best small rises in equilibrium employment. As labor supply for Minijob employment differs and may be characterized by much higher labor supply elasticities, employment effects are plausible in our case.

Crépon and Desplatz (2002) find positive employment effects of payroll tax reductions for French low wage workers in the 1990s. Cahuc et al. (2019) offer causal evaluations of temporary hiring subsidies for small French firms in 2008/09 and find positive employment effects. A separate literature evaluates the effect of subsidies on outcomes at the individual level, see, e.g., Murphy (2007), or Bingley and Lanot (2002).

As our instrument appears to be relevant only for small firms, we focus on establishments with fewer than ten employees.

Two studies investigate the price elasticities of heterogeneous labor inputs specifically including marginal employment for Germany. Jacobi and Schaffner (2008) find a high own-wage elasticity of marginal employment and modest effects of changes in the wages of marginal employment on demand for alternative types of labor. In simulation exercises, Freier and Steiner (2007) suggest that an increase in the contribution rate for marginal employment would have a modest negative effect on overall labor demand.

Freier and Steiner (2008) and Caliendo et al. (2016) evaluate the effectiveness of the Minijob program in facilitating re-entry to the labor market. Both teams focus on unemployed males and find, both, positive and negative effects of Minijob employment. Böheim and Weber (2011) evaluate a similar program in Austria and find negative effects of working in marginal employment when unemployed. About 10% of Minijob holders are registered as unemployed which allows up to 15 hours of paid employment (Körner et al. 2011; RWI 2012).

The 2003 reform also introduced Midijobs for monthly earnings between 400 and 800 Euro. Midijob employees pay regular income taxes. Their social insurance contributions increase on a sliding scale and reach the unsubsidized level at monthly earnings of 800 Euro.

For comparison, in 2016, unsubsidized employment was subject to total contribution rates close to 40% of earnings (DRV (Deutsche Rentenversicherung Bund) 2016a) about 20% for employers and employees, each.

Causal evidence on the effectiveness of the Hartz reforms in their entirety is hard to come by. For a discussion and additional references see, e.g., Akyol et al. (2013).

As of 2016, Minijob employment accounted for about 8% of hours worked in regular employment, i.e., part-time, full-time, and Minijob employment (we consider the average number of hours worked using SOEP data as in Appendix Table A.1 and the number of employees based on BA (Bundesagentur für Arbeit) (2018)).

The instrumental variables fixed effects estimator (we use Stata 14) applies the standard 2-stage-least squares estimator to within transformed variables; i.e., for each observation (i,t) on each variable (x), we use xi,t* = xi,t - mean (xi,•).

The table shows that we have enough variation to identify these effects separately. While the 2003 reform changed the contribution rates and the limits on earnings and hours worked, the 2006 reform affected only contribution rates, and the most recent 2013 reform affected only the earnings limit, leaving the contribution rates and hours limit unchanged. Alternatively, we used the indicators for earnings and hours limits as additional instruments. This specification strongly confirms our main results. However, it extends the group of compliers to establishments who also react to the earnings and hours limit, which unnecessarily complicates the interpretation.

In small establishments, we observe on average 1.1 and 1.8, in medium-sized establishments 4.9 and 18.8, and in large establishments 29.2 and 254.7 employees in the Minijob and unsubsidized employment categories, respectively.

About 36/41/23% of all Minijob employees are employed in small/middle/large establishments, respectively. This differs from the distribution of unsubsidized employment where about 15/37/48% of all unsubsidized employees are employed in small/middle/large establishments. Thus, Minijob employment is concentrated in small establishments, which account for 15% of unsubsidized and 36% of subsidized employment relationships.

We tested and rejected heterogeneous responses of the number of employees by gender.

One might be concerned about whether these averages accurately depict the working hours of individual establishments and offer sufficient variation in the dependent variable. To mitigate these concerns, we also used the predicted average number of working hours based on survey year, establishment’s size, industry, and location (federal state). We applied regression coefficients estimated separately by employment type using the SOEP data. This alternative approach yielded very similar results. Also, we confirmed that the number and development of hours worked in small establishments is similar to what we show in Appendix Table A.1. For simplicity, we use the volume indicators as in Appendix Table A.1 throughout our analyses.

We observe heterogeneous employment compositions across establishment sizes: linear regressions show a positive correlation between Minijob and unsubsidized employment in middle and large establishments confirming the findings of Hohendanner and Stegmaier (2012).

We investigated a potential correlation between the rate at which establishments drop out from the sample and the value of our instrument. We do not find such a correlation: the propensity to drop out from one year to the next slightly decreased between 2002 and 2003 and slightly increased between 2006 and 2007.

Generally, the distribution of small establishments across industries does not differ appreciably from that of larger establishments (see Appendix Table A.2). However, the share of small establishments in agriculture is more than twice as high as that among larger establishments. In contrast, there are fewer small establishments in manufacturing, particularly in food production, basic metal, and machinery. Not surprisingly, the vast majority of about three quarters of all establishments is in the tertiary sector with clearly a higher share of small than large establishments.

We found that this coding choice does not change the nature of our results. In addition, we offer a robustness test where we omit the 2003 and 2007 calendar years from the estimations.

As employers might respond to the reform by reconfiguring the composition of their work force in terms of full-time, part-time, apprentice, and Minijob employees, in principle the number of hours might respond differently than the number of employees to the reform.

In our setting, it is not possible to perform a valid placebo test. First, the period of observation does not contain enough years without changes in the instrument, which would allow us to evaluate placebo effects without covering periods affected by the actual reforms. In addition, as the reforms affected all firms and all Minijobs there are no placebo treatment groups.

Additionally, we estimated the model without time trend controls. The results remain statistically significant and negative with larger point estimates (results available upon request).

Note that we consider only average values as presented in Table A.3. The U1 contributions actually work like an insurance and the rates depend on the chosen coverage. Employers in the public sector do not have to contribute to the U3 system because they are not at risk of insolvency. Information on the contribution rates for the period prior to 2003 is unavailable. While we use zero values for the pre 2003 years in the estimations, the results are robust to fixing the value at that observed for 2003, i.e., at 1.3%.

In addition, we considered samples of establishments with 0–9 employees in the first year in which they appear in the data, and only establishments with 0–9 employees in 1999. In both cases, we find confirmation of significant substitution effects. In order to account for potential effects of endogenous establishment mortality, we also used a balanced panel of firms with 0–9 employees in 1999. Our results hold up in this setting as well.

We also estimated the models for the full sample. The results yield highly significant negative effects confirming the general patterns presented in Table 3. However, the effects’ magnitudes are implausibly large, which is mainly driven by a weak first-stage in the subsample of large establishments.

References

Adam, S., Phillips, D., & Roantree, B. (2019). 35 years of reforms: a panel analysis of the incidence of, and employee and employer responses to, social security contributions. Journal of Public Economics, 171, 29–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2018.05.010.

Ager, P., Hansen, C. W., & Jensen, P. S. (2018). Fertility and early-life mortality: evidence from smallpox vaccination in Sweden. Journal of the European Economic Association, 16(2), 487–521. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvx014.

Akyol, M., Neugart, M., & Pichler, S. (2013). Were the Hartz reforms responsible for the improved performance of the German labour market? Economic Affairs (Institute of Economic Affairs), 33(1), 34–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecaf.12002.

Anderson, P. A., & Meyer, B. D. (1997). The effects of firm specific taxes and government mandates with an application to the U.S. unemployment insurance program. Journal of Public Economics, 65, 119–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2727(96)01624-6.

Anderson, P. A., & Meyer, B. D. (2000). The effects of the unemployment insurance payroll tax on wages, employment, claims and denials. Journal of Public Economics, 78, 81–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2727(99)00112-7.

BA (Bundesagentur für Arbeit) (2010). Methodenbericht - Kurzfristige Beschäftigung, Bundesagentur für Arbeit, Nürnberg. https://statistik.arbeitsagentur.de/Statischer-Content/Grundlagen/Methodenberichte/Beschaeftigungsstatistik/Generische-Publikationen/Methodenbericht-Kurzfristige-Beschaeftigung.pdf [last access: 14 Mar, 2019].

BA (Bundesagentur für Arbeit) (2017). Arbeitsmarkt in Zahlen - Beschäftigungsstatistik Juni 2017. Nürnberg.

BA (Bundesagentur für Arbeit) (2018). Revision der Beschäftigungsstatistik 2017. Nürnberg. Statistik der Bundesagentur für Arbeit, Nürnberg.

Bachmann, R., Dürig, W., Frings, H., Höckel, L. S., & Flores, F. M. (2017). Minijobs nach Einführung des Mindestlohns - Eine Bestandsaufnahme, RWI Materialien Heft 114. Essen. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfwp-2017-0014.

Bennmarker, H., Mellander, E., & Öckert, B. (2009). Do regional payroll tax reductions boost employment? Labour Economics, 16, 480–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2009.04.003.

vom Berge, Philipp, Mario Bossler, and Joachim Möller (2016). Erkenntnisse aus der Mindestlohnforschung des IAB, IAB Stellungnahme 3/2016, IAB, Nürnberg. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/156267/1/857726226.pdf [last access: 18 Jan, 2020].

Berthold, Norbert and Mustafa Coban (2013). Mini- und Midijobs in Deutschland: Lohnsubventionierung ohne Beschäftigungseffekte?. Wirtschaftswissensch. Beiträge des Lehrstuhls für VWL, insb. Wirtschaftsordnung und Sozialpolitik, Nr. 119, Würzburg. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/ordo-2013-0115

Bingley, P., & Lanot, G. (2002). The incidence of income tax on wages and labour supply. Journal of Public Economics, 83, 173–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2727(01)00080-9.

Böheim, R., & Weber, A. (2011). The effects of marginal employment on subsequent labour market outcomes. German Economic Review, 12(2), 165–181.

Burda, Michael C. and Stefanie Seele (2016). No Role for the Hartz Reforms? Demand and Supply Factors in the German Labor Market 1993–2014, SFB 649 Discussion Paper 2016–010, Berlin. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/146179/1/849716004.pdf [last access: 18 Jan, 2020].

Cahuc, P., Carcillo, S., & Le Barbanchon, T. (2019). The effectiveness of hiring credits. Review of Economic Studies, 86(2), 593–626. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdy011.

Caliendo, M., & Wrohlich, K. (2010). Evaluating the German 'Mini-Job' reform using a natural experiment. Applied Economics, 42, 2475–2489. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840701858125.

Caliendo, M., Künn, S., & Uhlendorff, A. (2016). Earnings exemptions for unemployed workers: The relationship between marginal employment, unemployment duration and job quality. Labour Economics, 42, 177–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2016.07.003.

Caliendo, M., Fedorets, A., Preuss, M., Schroder, C., & Wittbrodt, L. (2018). The short-run employment effects of the German minimum wage reform. Labour Economics, 53, 46–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2018.07.002.

Card, D., Kluve, J., & Weber, A. (2010). Active labour market policy evaluations: A Meta-analysis. Economic Journal, 120(548), F452–F477. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2010.02387.x.

Card, D., Kluve, J., & Weber, A. (2018). What works? A meta analysis of recent active labor market program evaluations. Journal of the European Economic Association, 16(3), 894–931. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvx028.

Conley, T. G., Hansen, C. B., & Rossi, P. E. (2012). Plausibly exogenous. Review of Economics and Statistics, 94(1), 260–272. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00139.

Crépon, Bruno and Rozenn Desplatz (2002). The effects of payroll tax subsidies for low wage workers on firms level decisions, mimeo, CREST, France. ftp://193.146.129.230/pdf/papers/pew/Crepon.pdf [last access: 18 Jan, 2020].

Crépon, B., Duflo, E., Gurgand, M., Rathelot, R., & Zamora, P. (2013). Do labor market policies have displacement effects? Evidence from a clustered randomized experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(2), 531–580. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjt001.

Dahlberg, M., & Forslund, A. (2005). Direct displacement effects of labour market Programmes. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 107(3), 475–494. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9442.2005.00419.x.

Dimico, A. (2017). Size matters: the effect of the size of ethnic groups on development. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 79(3), 291–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/obes.12145.

DRV (Deutsche Rentenversicherung Knappschaft - Bahn - See / Minijob Zentrale) (2016). Aktuelle Entwicklungen im Bereich der geringfügigen Beschäftigung, IV. Quartal 2016, https://www.minijob-zentrale.de/DE/02_fuer_journalisten/02_berichte_trendreporte /quartalsberichte_archiv/2016/4_2016.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=1 [last access: Mar 14, 2019].

DRV (Deutsche Rentenversicherung Bund) (2016). Rentenversicherung in Zeitreihen, Ausgabe 13.10.2016. 22. Auflage, Berlin.

Eichhorst, Werner, Tina Hinz, Paul Marx, Andreas Peichl, Nico Pestel, Sebastian Siegloch, Erich Thode, and Verena Tobsch (2012). Geringfügige Beschäftigung: Situation und Gestaltungsoptionen. IZA Research Report No. 47, IZA Bonn. http://www.schiering.org/arhilfen/gfb/gfb-gestaltungsoptionen.pdf [last access: Jan 18, 2020].

Freier, Ronny and Viktor Steiner (2007). 'Marginal employment' and the demand for heterogeneous labour- empirical evidence from a multi-factor labour demand model for Germany, DIW Discussion Paper No. 662, Berlin. https://ssrn.com/abstract=961853 [last access: 18 Jan, 2020].

Freier, Ronny and Viktor Steiner (2008). 'Marginal employment': stepping stone or dead end? Evaluating the German experience, Zeitschrift für Arbeitsmarktforschung 41(2/3), 223–243. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1039521 [last access: 18 Jan, 2020].

Garsaa, A., & Levratto, N. (2015). Do labor tax rebates facilitate firm growth? An empirical study on French establishments in the manufacturing industry, 2004-2011. Small Business Economics, 45, 613–641. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-015-9653-1.

Gruber, J. (1997). The incidence of payroll taxation: evidence from Chile. Journal of Labor Economics, 15(3, pt.2), S72–S101. https://doi.org/10.1086/209877.

Hamermesh, D. S. (1993). Labor demand. Princeton: Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/2234647.

Hohendanner, Christian and Jens Stegmaier (2012). Geringfügige Beschäftigung in deutschen Betrieben - Umstrittene Minijobs. IAB-Kurzbericht 24/2012, Nürnberg. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/158393/1/kb2012-24.pdf [last access: 20 January, 2020].

Huttunen, K., Pirttilä, J., & Uusitalo, R. (2013). The employment effects of low-wage subsidies. Journal of Public Economics, 97, 49–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2012.09.007.

Jacobi, Lena and Sandra Schaffner (2008). Does marginal employment substitute regular employment?—a heterogeneous dynamic labor demand approach for Germany, Ruhr Economic Papers No. 56, RWI Essen. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1244507

Kangasharju, A. (2007). Do wage subsidies increase employment in subsidized firms? Economica, 74, 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0335.2006.00525.x.

Korkeamäki, O., & Uusitalo, R. (2009). Employment and wage effects of a payroll-tax cut—evidence from a regional experiment. International Tax and Public Finance, 16, 753–772. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-008-9088-6.

Körner, T., Puch, K., Frank, T., & Meinken, H. (2011). Geringfügige Beschäftigung in Mikrozensus und Beschäftigungsstatistik, Wirtschaft und Statistik, 1065-1085.

Körner, Thomas, Holger Meinken, and Katharina Puch (2013). Wer sind die ausschließlich geringfügig Beschäftigten? Eine Analyse nach sozialer Lebenslage, Wirtschaft und Statistik (Jan. 2013), 42–61. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Methoden/WISTA-Wirtschaft-und-Statistik/2013/01/geringfuegig-beschaeftigte-012013.pdf;jsessionid=E22C4541FC6A8267993B1654FD50A506.internet741?__blob=publicationFile [last access: 20 Jan, 2020].

Murphy, K. J. (2007). The impact of unemployment insurance taxes on wages. Labour Economics, 14, 457–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2006.02.002.

MZ (Minijob-Zentrale) (2018). Die Entwicklung der Abgaben an die Minijob-Zentrale, see https://www.minijob-zentrale.de/DE/02_fuer_journalisten/03_entwicklung/node.html [last access Mar 14, 2019].

Nybom, M. (2017). The distribution of lifetime earnings returns to college. Journal of Labor Economics, 35(4), 903–952. https://doi.org/10.1086/692475.

RWI (Rheinisch-Westfälisches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung) (2012). Studie zur Analyse der geringfügigen Beschäftigungsverhältnisse, Dezember 2012, Projektbericht, Essen. http://www.rwiessen.de/media/content/pages/publikationen/rwiprojektberichte/PB_Analyse-der-Minijobs.pdf [last access: 20 Jan, 2020].

Saez, E., Slemrod, J., & Gierts, S. H. (2012). The elasticity of taxable income with respect to marginal tax rates: a critical review. Journal of Economic Literature, 50(1), 1–50. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.50.1.3.

Saez, E., Schoefer, B., & Seim, D. (2019). Payroll taxes, firm behavior, and rent sharing: evidence from a young workers' tax cut in Sweden. American Economic Review, 109(5), 1717–1763. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20171937.

Schmucker, Alexandra, Stefan Seth, Johannes Ludsteck, Johanna Eberle, and Andreas Ganzer (2016). Establishment History Panel 1975–2014. FDZ-Datenreport, 03/2016 (en), Nürnberg. http://doku.iab.de/fdz/reporte/2016/DR_03-16.pdf [last access: 18 Jan, 2020].

STBA (Statistisches Bundesamt) (2017). Verdienste und Arbeitskosten. Arbeitnehmerverdienste. Fachserie 16 Reihe 2.1, 1. Vierteljahr 2017, Wiesbaden. https://www.destatis.de/GPStatistik/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/DEHeft_derivate_00035297/2160210173214_korr12012018.pdf [last access: 20 Jan, 2020].

Wagner, G. G., Frick, J. R., & Schupp, J. (2007). The German socio-economic panel study (SOEP)—scope, evolution and enhancements. Schmollers Jahrbuch, 127(1), 139–169. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1028709.

Wang, L. (2013). How does education affect the earnings distribution in urban China? Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 75(3), 435–454. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0084.2012.00697.x.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gesine Stephan, Ragnhild Camilla Schreiner, and participants of the annual meeting of the Employment and Social Protection Group at cesifo Munich, of the social policy group of the German Economic Association, of section 25 of the German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina, the 10th Norwegian-German Seminar on Public Economics at cesifo Munich, the EEA 2018, EALE 2018,Verein für Socialpolitik 2018, and IIPF 2018 meetings as well as of seminars at FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg, Louvain-la-Neuve, and IOS Regensburg for helpful comments.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL. We gratefully acknowledge funding by grant CY82/1-1 of the German Research Foundation

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Collischon, M., Cygan-Rehm, K. & Riphahn, R.T. Employment effects of payroll tax subsidies. Small Bus Econ 57, 1201–1219 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00344-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00344-w

Keywords

- Wage subsidy

- Minijob

- Labor demand

- Substitution effect

- Crowding out effect

- Displacement effect

- Employment

- Payroll tax