Abstract

Background

Understanding Black women’s Papanicolaou (Pap) screening experiences can inform efforts to reduce cancer disparities. This study examined experiences among both US-born US Black women and Sub-Saharan African immigrant women.

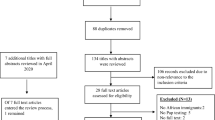

Method

Using a convergent parallel mixed methods design, Black women born in the USA and in Sub-Saharan Africa age 21–65 years were recruited to participate in focus groups and complete a 25-item survey about patient-centered communication and perceived racial discrimination. Qualitative and quantitative data were integrated to provide a fuller understanding of results.

Results

Of the 37 participants, 14 were US-born and 23 were Sub-Saharan African-born Black women. The mean age was 40.0 ± 11.0, and 83.8% had received at least one Pap test. Five themes regarding factors that impact screening uptake emerged from the focus groups: (1) positive and negative experiences with providers; (2) provider communication and interaction; (3) individual barriers to screening uptake, (4) implicit bias, discrimination, and stereotypical views among providers, and (5) language barrier. Survey and focus group findings diverged on several points. While focus group themes captured both positive and negative experiences with provider communication, survey results indicated that most of both US-born and Sub-Saharan African-born women experienced positive patient-centered communication with health care providers. Additionally, during focus group sessions many participants described experiences of discrimination in health care settings, but less than a third reported this in the survey.

Conclusion

Black women’s health care experiences affect Pap screening uptake. Poor communication and perceived discrimination during health care encounters highlight areas for needed service improvement to reduce cervical cancer disparities.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Giaquinto AN, Miller KD, Tossas KY, Winn RA, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African American/Black People 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(3):202–29. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21718.

Adunlin G, Cyrus JW, Asare M, Sabik LM. Barriers and facilitators to breast and cervical cancer screening among immigrants in the United States. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019;21(3):606–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-018-0794-6.

Adegboyega A, Hatcher J. Factors influencing pap screening use among African immigrant women. J Transcult Nurs. 2017;28(5):479–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659616661612.

Harcourt N, Ghebre RG, Whembolua GL, Zhang Y, Warfa Osman S, Okuyemi KS. Factors associated with breast and cervical cancer screening behavior among African immigrant women in Minnesota. J Immigr Minor Health. 2014;16(3):450–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-012-9766-4.

Nolan J, Renderos TB, Hynson J, Dai X, Chow W, Christie A, Mangione TW. Barriers to cervical cancer screening and follow-up care among black women in Massachusetts. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2014;43(5):580–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/1552-6909.12488.

Christy K, Kandasamy S, Majid U, Farrah K, Vanstone M. Understanding Black women’s perspectives and experiences of cervical cancer screening: a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2021;32(4):1675–97. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2021.0159.

Wearn A, Shepherd L. Determinants of routine cervical screening participation in underserved women: a qualitative systematic review. Psychol Health. 2022:1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2022.2050230.

Mouton CP, Carter-Nolan PL, Makambi KH, Taylor TR, Palmer JR, Rosenberg L, Adams-Campbell LL. Impact of perceived racial discrimination on health screening in black women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(1):287–300. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.0.0273.

Logan RG, Daley EM, Vamos CA, Louis-Jacques A, Marhefka SL. “When is health care actually going to be care?” The lived experience of family planning care among young Black women. Qual Health Res. 2021;31(6):1169–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732321993094.

Gary F, Still C, Mickels P, Hassan M, Evans E. Muddling through the health system: experiences of three groups of black women in three regions. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc: JNBNA. 2015;26(1):22–8.

Sutton AL, Hagiwara N, Perera RA, Sheppard VB. Assessing perceived discrimination as reported by Black and White women diagnosed with breast cancer. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;8(3):589–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00817-4.

Chinn JJ, Martin IK, Redmond N. Health equity among Black women in the United States. J Womens Health. 2021;30(2):212–9. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2020.8868.

Adegboyega AO, Hatcher J. Unequal access: African immigrants and American health care. Ky Nurse. 2016;64(1):10–2.

McRoy L, Epané J, Ramamonjiarivelo Z, Zengul F, Weech-Maldonado R, Rust G. Examining the relationship between self-reported lifetime cancer diagnosis and nativity: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011–2018. Cancer Causes Control. 2022;33(2):321–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-021-01514-1.

Farr DE, Cofie LE, Brenner AT, Bell RA, Reuland DS. Sociodemographic correlates of colorectal cancer screening completion among women adherent to mammography screening guidelines by place of birth. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01694-1.

Creswell JW, Clark VLP. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Los Angeles: Sage publications; 2017.

Leech NL, Onwuegbuzie AJ. Guidelines for conducting and reporting mixed research in the field of counseling and beyond. J Couns Dev. 2010;88(1):61–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00151.x.

US preventive Services Task Force. Cervical Cancer Screening. 2018. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/cervical-cancer-screening.

Singhal A, Jackson JW. Perceived racial discrimination partially mediates racial-ethnic disparities in dental utilization and oral health. J Public Health Dent. 2022;82:63–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/jphd.12515.

Hausmann LR, Jeong K, Bost JE, Ibrahim SA. Perceived discrimination in health care and use of preventive health services. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1679–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0730-x.

Finney Rutten LJ, Augustson E, Wanke K. Factors associated with patients’ perceptions of health care providers’ communication behavior. J Health Commun. 2006;11(S1):135–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730600639596.

Otter. ai. 2019. https://otter.ai

Tekeste M, Hull S, Dovidio JF, Safon CB, Blackstock O, Taggart T, et al. Differences in medical mistrust between black and white women: implications for patient–provider communication about PrEP. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(7):1737–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2283-2.

Filler T, Jameel B, Gagliardi AR. Barriers and facilitators of patient centered care for immigrant and refugee women: a scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09159-6.

Cuevas AG, O'Brien K, Saha S. African American experiences in healthcare:“I always feel like I’m getting skipped over”. Health Psychol. 2016;35(9):987–95. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000368.

Anderson JN, Graff JC, Krukowski RA, Schwartzberg L, Vidal GA, Waters TM, et al. “Nobody will tell you. You’ve got to ask!”: an examination of patient-provider communication needs and preferences among Black and White women with early-stage breast cancer. Health Commun. 2021;36(11):1331–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2020.1751383.

Chawla N, Blanch-Hartigan D, Virgo KS, Ekwueme DU, Han X, Forsythe L, et al. Quality of patient-provider communication among cancer survivors: findings from a nationally representative sample. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(12):e964–73.

Jain N. Survey versus interviews: comparing data collection tools for exploratory research. Qual Rep. 2021;26(2):541–54. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2021.4492.

Oei TI, Zwart FM. The assessment of life events: self-administered questionnaire versus interview. J Affect Disord. 1986;10(3):185–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-0327(86)90003-0.

Glackin EB, Forbes D, Heberle AE, Carter AS, Gray SA. Caregiver self-reports and reporting of their preschoolers’ trauma exposure: discordance across assessment methods. Traumatology. 2019;25(3):172–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000179.

Blair IV, Steiner JF, Fairclough DL, Hanratty R, Price DW, Hirsh HK, et al. Clinicians’ implicit ethnic/racial bias and perceptions of care among Black and Latino patients. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(1):43–52. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1442.

Cooper LA, Roter DL, Carson KA, Beach MC, Sabin JA, Greenwald AG, Inui TS. The associations of clinicians’ implicit attitudes about race with medical visit communication and patient ratings of interpersonal care. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):979–87. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300558.

Beach MC, Saha S, Korthuis PT, Sharp V, Cohn J, Wilson IB, et al. Patient–provider communication differs for black compared to white HIV-infected patients. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(4):805–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-009-9664-5.

Johnson RL, Roter D, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Patient race/ethnicity and quality of patient–physician communication during medical visits. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(12):2084–90. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.94.12.2084.

Shen MJ, Peterson EB, Costas-Muñiz R, Hernandez MH, Jewell ST, Matsoukas K, Bylund CL. The effects of race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication: a systematic review of the literature. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018;5(1):117–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-017-0350-4.

Benjamins MR, Middleton M. Perceived discrimination in medical settings and perceived quality of care: a population-based study in Chicago. PloS One. 2019;14(4):e0215976. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215976.

Borrell LN, Kiefe CI, Williams DR, Diez-Roux AV, Gordon-Larsen P. Self-reported health, perceived racial discrimination, and skin color in African Americans in the CARDIA study. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(6):1415–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.008.

Van Houtven CH, Voils CI, Oddone EZ, Weinfurt KP, Friedman JY, Schulman KA, Bosworth HB. Perceived discrimination and reported delay of pharmacy prescriptions and medical tests. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(7):578–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-005-0104-6.

Ben J, Cormack D, Harris R, Paradies Y. Racism and health service utilisation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2017;12(12):e0189900. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189900.

Arif SA, Schlotfeldt J. Gaps in measuring and mitigating implicit bias in healthcare. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:633565. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.633565.

Fuzzell LN, Perkins RB, Christy SM, Lake PW, Vadaparampil ST. Cervical cancer screening in the United States: challenges and potential solutions for underscreened groups. Prev Med. 2021;144:106400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106400.

Genoff MC, Zaballa A, Gany F, Gonzalez J, Ramirez J, Jewell ST, Diamond LC. Navigating language barriers: a systematic review of patient navigators’ impact on cancer screening for limited English proficient patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(4):426–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3572-3.

Karliner LS, Jacobs EA, Chen AH, Mutha S. Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(2):727–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00629.x.

Cudjoe J, Nkimbeng M, Turkson-Ocran RA, Commodore-Mensah Y, Han HR. Understanding the Pap testing behaviors of African immigrant women in developed countries: a systematic review. J Immigr Minor Health. 2021;23(4):840–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-020-01119-x.

Vu N. Essential and exposed: a novel solution to improve healthcare access for undocumented Mexican immigrants in the United States. Houston J Health Law Policy. 2023:1–37.

Van Der Heide I, Uiters E, Jantine Schuit A, Rademakers J, Fransen M. Health literacy and informed decision making regarding colorectal cancer screening: a systematic review. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(4):575–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckv005.

Peterson EB, Ostroff JS, DuHamel KN, D’Agostino TA, Hernández M, Canzona MR, Bylund CL. Impact of provider-patient communication on cancer screening adherence: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2016;93:96–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.09.034.

Friedman AM, Hemler JR, Rossetti E, Clemow LP, Ferrante JM. Obese women’s barriers to mammography and pap smear: the possible role of personality. Obesity. 2012;20(8):1611–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2012.50.

Poorolajal J, Jenabi E. The association between BMI and cervical cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2016;25(3):232–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000164.

Clarke MA, Fetterman B, Cheung LC, Wentzensen N, Gage JC, Katki HA, Schiffman M. Epidemiologic evidence that excess body weight increases risk of cervical cancer by decreased detection of precancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(12):1184. 1184–1191. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.75.3442.

Gnade CM, Hill EK, Botkin HE, Hefel AR, Hansen HE, Sheets KA, et al. Effect of obesity on cervical cancer screening and outcomes. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2020;24(4):358–62. https://doi.org/10.1097/LGT.0000000000000570.

Aleshire ME, Adegboyega A, Escontrías OA, Edward J, Hatcher J. Access to care as a barrier to mammography for Black women. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2021;22(1):28–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527154420965537.

Fang CY, Ragin CC. Addressing disparities in cancer screening among US immigrants: progress and opportunities. Cancer Prev Res. 2020;13(3):253–60. https://doi.org/10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-19-0249.

Zhang X, Li P, Zhang C, Guo P, Wang J, Liu N, et al. Breast cancer screening practices and satisfaction with healthcare providers in Chinese women: a cross-sectional study. Cancer Nurs. 2022;45(2):E573–81. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000942.

Funding

Research reported was supported by a National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute grant (K01CA251487: Adegboyega). Support for the use of REDCap was provided by the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences through grant number UL1TR001998. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AA and GMM conceptualized the paper. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by AA, AA, AD, and GMM. AA and LW were responsible for interpreting the results. The first draft of the manuscript was written by AA and AA, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics approval was obtained from the Office of Research Integrity at the University of Kentucky (Jan 10/2021/protocol#: 60704).

Consent to Participate

All participants provided written informed consented prior to participation in the study.

Consent for Publication

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Adebola, A., Adaeze, A., Adeyimika, D. et al. Experiences and Challenges of African American and Sub-Saharan African Immigrant Black Women in Completing Pap Screening: a Mixed Methods Study. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 11, 1405–1417 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01617-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01617-2