Abstract

Background

Migrants experience disparities in healthcare quality, in particular women migrants. Despite international calls to improve healthcare quality for migrants, little research has addressed this problem. Patient-centred care (PCC) is a proven approach for improving patient experiences and outcomes. This study reviewed published research on PCC for migrants.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review by searching MEDLINE, CINAHL, SCOPUS, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library for English-language qualitative or quantitative studies published from 2010 to June 2019 for studies that assessed PCC for adult immigrants or refugees. We tabulated study characteristics and findings, and mapped findings to a 6-domain PCC framework.

Results

We identified 581 unique studies, excluded 538 titles/abstracts, and included 16 of 43 full-text articles reviewed. Most (87.5%) studies were qualitative involving a median of 22 participants (range 10–60). Eight (50.0%) studies involved clinicians only, 6 (37.5%) patients only, and 2 (12.5%) both patients and clinicians. Studies pertained to migrants from 19 countries of origin. No studies evaluated strategies or interventions aimed at either migrants or clinicians to improve PCC. Eleven (68.8%) studies reported barriers of PCC at the patient (i.e. language), clinician (i.e. lack of training) and organization/system level (i.e. lack of interpreters). Ten (62.5%) studies reported facilitators, largely at the clinician level (i.e. establish rapport, take extra time to communicate). Five (31.3%) studies focused on women, thus we identified few barriers (i.e. clinicians dismissed their concerns) and facilitators (i.e. women clinicians) specific to PCC for migrant women. Mapping of facilitators to the PCC framework revealed that most pertained to 2 domains: fostering a healing relationship and exchanging information. Few facilitators mapped to the remaining 4 domains: address emotions/concerns, manage uncertainty, make decisions, and enable self-management.

Conclusions

While few studies were included, they revealed numerous barriers of PCC at the patient, clinician and organization/system level for immigrants and refugees from a wide range of countries of origin. The few facilitators identified pertained largely to 2 PCC domains, thereby identifying gaps in knowledge of how to achieve PCC in 4 domains, and an overall paucity of knowledge on how to achieve PCC for migrant women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The rate of both voluntary (immigrants move for better opportunities in another country) and involuntary (refugees move to escape dangerous conditions in their home country) migration has been steadily rising [1]. From 2000 to 2017, the total number of international migrants rose from 173 million to 258 million, an increase of 49% [2]. Research shows that migrants are less likely than the general population to experience high-quality health care [3]. For example, a systematic review (67 studies, 1996–2009) of population-based studies involving immigrants in the United States found they were less likely to have medical insurance, or access to a regular healthcare provider, preventive care, tests or services; and were more likely to report insufficient time with clinicians and not being engaged by clinicians [4]. Interviews with immigrants of various ethnic origins in the Netherlands [5], and with Asian immigrants in the United States [6] revealed they had experienced negative health care events, described as abusive or discriminatory and potentially dangerous, due to language barriers and cultural differences. Similarly, a scoping review (27 studies, 1993–2014) of studies based in Canada involving immigrants from various ethnic origins found that access to and quality of primary care was influenced by communication and cultural factors [7].

Several organizations have advocated for action to improve the health of immigrants and refugees. For example, the University of Edinburgh, the European Public Health Association and NHS Health Scotland hosted the First World Congress on Migration, Ethnicity, Race and Health in May 2018 to explore how to improve the quality of care for migrants [8]. A scoping review (83 studies, 1990–2015) of interventions used to improve the health of migrants conducted by The Worldwide Universities Network’s Health Outcomes of Migration Events research group revealed that all interventions aimed to educate migrants to prevent or self-manage conditions such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease [9]. The authors concluded that more research was needed to fully investigate factors influencing quality of care for a broader range of conditions as the first step in developing interventions to improve the organization, delivery and outcomes of health services for migrants. The World Health Organization (WHO), in collaboration with the United Nations and the International Organization for Migration, generated a framework of priorities to promote the health of immigrants and refugees [2]. The WHO Global Action Plan emphasizes the need to improve the quality, acceptability, availability and accessibility of health care services for migrants.

The WHO Global Action Plan makes special mention of improving the health and well-being of women given considerable evidence of persistent gendered inequities in health care quality in both lower- and higher-resourced countries [10,11,12]. For example, immigrant women have experienced poor access to breast and cervical cancer screening [13], dissatisfaction with health care experiences for maternity [14], contraceptive counseling [15], and menopause [16], and may be uncomfortable with physical exams even when performed by a woman physician [7]. A scoping review (29 studies, 1995–2016) of interventions to reduce adverse health outcomes resulting from gender bias among immigrant populations revealed that most studies focused on counseling or education on domestic violence among Latino populations in the United States [17]. Clearly, more research is needed on how to improve quality of care for migrant women for the range of health issues and populations.

The concept of cultural competence has emerged in response to widespread disparities in care by culture, race, ethnicity, religion, gender and sexual orientation, and refers to care that respects patients’ health beliefs about their illness and its causes, interprets health issues from a biopsychosocial rather than biomedical context, involves communication in language accessible to patients, and engages patients in developing a mutually agreeable treatment plan [18]. Models or frameworks of cultural competence emphasize the need for clinicians to be culturally competent, referring to understanding and respecting cultural differences, but otherwise provide limited guidance on approaches or processes to practice cultural competence at the point of care [19]. Culturally competent care and patient-centred care (PCC) share many of the same principles and both aim to tailor care to individual patients, yet considerably more research has explored determinants and impacts of PCC [18]. PCC is a multi-dimensional approach whereby clinicians foster a healing relationship, exchange information, respond to emotions, manage uncertainty, engage patients in decisions, and enable self-management, and in so-doing, tailor care to an individual’s clinical needs, life circumstances, and personal values and preferences, all of which may be influenced by culture, race, ethnicity, religion, gender and sexual orientation [20]. Moreover, PCC has been associated with a range of beneficial patient-important and clinical outcomes [21]. PCC is one way to reduce gendered disparities in health care quality among immigrant and refugee women [17]. The purpose of this study was to review published research on determinants (barriers, facilitators) or approaches of PCC specifically for immigrant and refugee women. This knowledge could be used to design and evaluate strategies or interventions that improve migrant women’s health care experiences and outcomes.

Methods

Approach

We conducted a scoping review [22, 23], and complied with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis criteria for scoping reviews (PRISMA-Scr) [24]. While similar in rigour to traditional systematic reviews, scoping reviews include studies with a range of research designs; focus on characterizing the literature to describe the nature of existing knowledge and identify issues for which further primary research is needed; and do not assess the methodological quality of included studies [22, 23]. A scoping review is comprised of five steps: scoping, searching, screening, data extraction and data analysis [22, 23]. We did not require research ethics board approval as data were publicly available, and we did not register a protocol.

Scoping

The scoping step involved becoming familiar with the literature on this topic. We conducted a preliminary search in MEDLINE using Medical Subject Headings: “emigrants and immigrants” or “refugees” and “patient-centered care”. Two research assistants, TF and BJ, with guidance from ARG, screened titles and abstracts of the search results to identify examples of relevant studies. We used this insight to develop eligibility criteria and generate a more detailed search strategy.

Eligibility criteria

We drafted eligibility criteria according to the Population, Issues, Comparisons and Outcomes (PICO) framework. Population referred to immigrant or refugee adults aged 18 or older with any health issue in any setting of care (i.e. primary, hospital) or country. We did not restrict eligible studies to women only participants, as studies with both women and men might report sub-analyses by sex or gender. As many authors do not distinguish sex (female/male biological attributes) and gender (socially-constructed roles, behaviours and identities), we reported results for women, and defined women as individuals who self-identified as women or were identified as such by authors. We also included studies where participants were clinicians (physicians, nurses), as such research might aim to reveal determinants or approaches of PCC for migrant women. The intervention of interest included barriers, facilitators, approaches, strategies, programs or tools used to promote or support PCC by influencing patient and/or clinician awareness, knowledge, self-efficacy, attitude, adoption or implementation of PCC for immigrants or refugees. We defined PCC as partnership between clinicians and patients (also family, care partners) to discuss and tailor care according to individual needs and characteristics [20]. To be eligible, the article had to employ the term “patient-centred” or a synonymous term (i.e. person-centred, client-centred) or variant spelling of these terms, or be indexed with the Medical Subject Heading “patient-centered care”. Comparisons referred to studies that explored or compared patient and/or clinician views about what constitutes PCC or experiences of PCC, described approaches desired or employed to achieve PCC (evaluated alone, before-after the intervention, or in comparison with another intervention), identified determinants (facilitators, barriers) of PCC, or evaluated the impact of interventions designed to promote or support PCC. Outcomes included any reported by eligible studies including but not limited to: awareness, understanding, experiences or impacts of PCC; elements of PCC; patient engagement in or satisfaction with care; relationship between the patient and clinicians; or the influence on health outcomes as a result of the above factors. Eligible study designs included qualitative (interviews, focus groups, qualitative case studies), quantitative (questionnaires, randomized controlled trials, time series, before/after studies, prospective or retrospective cohort studies, case control studies) or mixed-methods studies published in English-language in peer-reviewed journals. We included studies published from 2010, when the concepts of cultural competency and patient-centred care became prominent [18], to current.

We excluded studies in which the setting was long-term care or the patient-centred medical home; the population was family or care partners only, or allied healthcare professionals; or the intervention pertained to the illness experience rather than the care experience, views about the treatment modality rather than the care experience; or patient engagement in research or health system planning. Protocols, editorials, commentaries, letters, news items, or meeting abstracts or proceedings were not eligible. We did not include systematic reviews, but screened references for eligible primary studies.

Searching

The search strategy (Additional File 1) was developed by ARG, trained as a medical librarian, and complied with the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategy reporting guidelines [25]. We searched MEDLINE, CINAHL, SCOPUS, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library on June 5, 2019. We did not include the term “woma(e)n” or “female” in the search strategy, choosing instead to to search for all studies of any migrant and PCC, as this might have reduced the number of studies retrieved by eliminating studies involving both men and women that were not also indexed by “woma(e)n” or “female”.

Screening

To pilot test screening, TF, BJ and ARG independently screened titles and abstracts for the first 25 search results against eligibility criteria, and discussed discrepancies, and how to interpret and apply the eligibility criteria. Thereafter, TF and BJ independently screened all remaining titles and abstracts, and ARG resolved discrepancies or uncertainties. TF and BJ retrieved full-text items, which they screened concurrent with data extraction.

Data extraction

We developed a data extraction form to collect information on author, publication year, country, study objective, research design including participant characteristics (immigrant or refugee, country of origin, clinician specialty), clinical topic, intervention or aspect of PCC studied, and results. To pilot test data extraction, TF, BJ and ARG independently extracted data from two articles, and compared and discussed findings to refine the data extraction form and the approach to data extraction. Thereafter, TF and BJ independently extracted data from all articles, and ARG resolved discrepancies or uncertainties, and independently checked completed data tables. We did not assess study quality as this is not required in a scoping review [22, 23].

Data analysis

We used summary statistics to report study characteristics (date published, country, research design, number and type of participants, type of migrant, country of origin, and whether findings were specific to women), and clinical topic. We summarized facilitators and barriers of PCC in tabular format and text by level (patient, clinician, organization/system), type of study participant (patients, clinicians) and those that pertained specifically to care for women. To further characterize facilitators that emerged from included studies, we mapped them to an established framework of PCC, chosen because it was rigorously developed and comprehensive, comprised of 31 elements organized in 6 domains: foster a healing relationship, exchange information, respond to emotions, manage uncertainty, make decisions, and enable self-management [20]. We then summarized the number and type of PCC domains addressed by included studies for migrants in general, and for women migrants.

Results

Search results

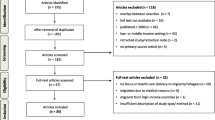

A total of 581 unique articles were identified, and 538 were excluded upon screening of titles and abstracts. Among 43 full-text articles that were screened, 27 were excluded because they were not an eligible publication type (13), not focused on PCC (9) or not focused on immigrants or refugees (5). We did not identify additional items in the references of eligible studies. A total of 16 studies were eligible for review (Fig. 1). Data extracted from included studies are available in Additional File 2 [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41].

Study characteristics

Study characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Studies were published between 2010 and 2019 (50.0% in last 3 years). Studies were conducted in the United States (6), Australia (3), Canada (2), Netherlands (2), Sweden (2) and Norway (1). Most (14, 87.5%) studies were qualitative (interviews, focus groups), and 2 (12.5%) employed a questionnaire. Qualitative studies involved a median of 22 participants (range 10 to 60). One survey included 107 participants, and the other survey included 598 participants. Eight (50.0%) studies involved clinicians only, 6 (37.5%) patients only, and 2 (12.5%) both patients and clinicians.

A total of 9 (56.3%) studies pertained to care in general, while others focused on family planning or maternity care (4, 25.0%), mental health care (2, 12.5%), and medication management (1, 6.3%). All studies explored facilitators or barriers of care for immigrants or refugees. No studies developed or evaluated strategies, interventions or tools aimed at either migrants or clinicians to improve quality of care.

Most studies were specific to immigrants (9, 56.3%), while 4 (25.0%) were specific to refugees, 2 (12.5%) referred to “non-natives”, and 1 (12.5%) study involved both immigrants and refugees. Among the 8 studies involving patients or patients and clinicians, all noted the country of origin (Afghanistan, Bhutan, Brazil, Burma, Cambodia, Cape Verde, China, Indonesia, Iraq, Ireland, Mexico, Morocco, Portugal, Russia, Somalia, South America, Surinam, Syria, Turkey, United States) or ethnicity/culture (Portuguese, Muslim) of patients. Of the remaining 8 studies involving clinicians only, 4 (50.0%) pertained to immigrants or refugees in general, and 4 (50.0%) pertained to specific groups (Afghanistan, Asia, Australia, Belgium, Burma, Eritrea, Europe, Democratic Republic of Congo, Hungary, Iraq, Morocco, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Pakistan, South America, Sudan, Syria, Turkey).

Barriers of caring for migrants

Eleven (68.8%) studies reported barriers of caring for immigrants/refugees [26,27,28, 31, 32, 34, 35, 37,38,39,40]. Table 2 summarizes barriers by level (patient, clinician, organization or system) and who articulated the barrier (patient, clinician, both). At the patient level, both patients and clinicians viewed language as a patient-level barrier. Clinicians thought that culture influenced patient views about health and illness, expectations of clinicians or the healthcare system, and acceptance of or adherence to procedures or treatment. Patients identified few patient-level barriers of care.

At the clinician level, patients and clinicians agreed that language, culture and knowledge barriers resulted in longer consultations. Clinicians noted they lacked training in cultural competency. They also said it was challenging to be culturally competent without stereotyping, and to deliver medical care while accommodating culture. Patients said that clinicians were busy and rushed, leaving little time for communication, resulting in delayed diagnoses.

At the organization or system level, clinicians felt that remuneration was insufficient for the additional time required to care for immigrants or refugees. They also noted a lack of language services, or that interpreters were inaccurate and using them was time-consuming. Instead, they relied on family members to interpret, but recognized privacy and ethical issues of doing so. Patients identified few barriers at the organization or system level.

Facilitators of caring for migrants

Ten (62.5%) studies reported facilitators of caring for immigrants/refugees [27,28,29,30,31, 33, 36, 38,39,40]. Table 3 summarizes facilitators by level (patient, clinician, organization or system) and who articulated the barrier (patient, clinician, both). Neither patients nor clinicians identified patient-level facilitators.

At the clinician level, both patients and clinicians identified numerous facilitators. Most frequently, they recommended establishing rapport by greeting and welcoming the patient, taking time to chat informally, and adopting a friendly, caring and respectful manner. Other facilitators suggested by both patients and clinicians included clear communication (speak slowly, use short sentences, explain topics in various ways, avoid medical jargon, employ audiovisual rather than print information), take extra time to check comprehension, become familiar with the individual patient’s culture and migration journey, accommodate and respect cultural differences. Some patients and clinicians preferred skilled interpreters while others preferred family members to assist with communication. Patients and clinicians also viewed doctors of the same culture or gender as a facilitator. Clinician-level facilitators proposed by clinicians included booking longer consultations or dividing tasks into multiple consultations, coordinating internal and external appointments, and personal desire or dedication to help immigrants and refugees. Clinician-level facilitators suggested by patients included listening to patients, asking questions, acknowledging concerns, and treating the patient as a person and not a disease.

At the organization or system level, study participants identified few facilitators. Both patients and clinicians recommended orientation sessions or tours of health care facilities or systems, and multidisciplinary teamwork. Clinicians recommended access to language services and partnerships with community agencies. No patients identified organizational or system level facilitators.

Barriers and facilitators of caring for women migrants

Five (31.3%) of 16 included studies focused on women. Of those, 2 (40.0%), involved women as participants [32, 36], 2 (40.0%) involved clinicians as participants [27, 34], and 1 (20.0%) study included both [40]. Among the 5 women-focused studies, 4 (80.0%) pertained to family planning or maternity care [27, 32, 34, 36], and 1 (25.0%) focused on the general care of Muslim women [40]. Other studies did not explore issues specific to women or report sub-analyses by gender. Barriers and facilitators of caring for women immigrants/refugees are summarized in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Barriers noted by both women and clinicians at the patient-level included decision-making by the family rather than the individual woman, economic constraints limiting access to care, and lack of trust in the healthcare system. Clinicians noted that patient-level barriers among women included little knowledge about disease processes, female anatomy, reproduction or contraceptives; the influence of culture or religion on contraceptive decisions leading to unplanned pregnancy and abortion; and that women feared family violence if contraceptive use, pregnancy or abortion were discovered. No women identified patient-level barriers. Both women and clinicians noted that lack of knowledge about culture or religion was a clinician-level barrier. Clinicians did not identify clinician-level barriers. Women said that clinicians ignored or dismissed their concerns, provided little information about potential complications or the reason for adverse outcomes, and behaved disrespectfully or made disparaging remarks. At the organization or system level, only clinicians identified a barrier: lack of guidelines to help them care for immigrant or refugee women.

With respect to facilitators, both women and clinicians noted that patient communication skills or style was a facilitator. No other patient-level facilitators were identified by women or clinicians. At the clinician level, both women and clinicians said that clinician communication skills, gender and ethnicity or religion were facilitators. No clinicians identified clinician-level facilitators. Women recommended that clinicians take time to ask questions, assume a non-judgmental tone or manner, and provide information so that women could participate in decisions. No women or clinicians identified organization or system level facilitators.

Other comparisons

We compared barriers and facilitators articulated by patients based on type of care (Additional File 2). Views and experiences pertaining to mental health care and inpatient care were similar to those of general/primary care. With respect to maternity care, women expressed barriers and facilitators similar to general/primary care, but also noted that family influence on decisions was a barrier, and women physicians was a facilitator. We compared barriers and facilitators based on research design (Additional File 2). The majority of included studies collected data using qualitative methods. Studies that employed survey methods generated similar barriers (language and culture differences, lack of clinician training and time) and facilitators (clinician communication skills, longer appointments for discussion/questions) as did qualitative studies. We also compared barriers and facilitators articulated by patients based on migrant status (Additional File 3). There were no clear differences in barriers and facilitators described by refugees versus immigrants. In the only study of immigrant patients to explore barriers, language differences emerged as a challenge. This was confirmed by refugees, who also said that differences in culture, and lack of clinician training and time were barriers. With respect to facilitators, both refugees and immigrants recommended that clinicians establish rapport, and take the time to communicate clearly and address questions.

Patient-centred care for migrants

Table 4 shows facilitators of PCC for migrants mapped to an established PCC framework [20]. In total, 33 facilitators were relevant to immigrants or refugees in general. While these general facilitators spanned all PCC domains, most (23, 69.7%) pertained to the 2 domains of fostering a healing relationship and exchanging information. Few pertained to the remaining 4 domains: address emotions/concerns, manage uncertainty, make decisions, and enable self-management. Only 6 facilitators were specific to women, and these mapped to 3 PCC domains: foster a healing relationship, exchange information, and make decisions.

Discussion

This scoping review of PCC for immigrants and refugees identified few studies overall and even fewer that focused on PCC for women. Most studies focused on care in general rather than specific diseases or healthcare issues, thus PCC for migrants with specific conditions remains unknown. All studies explored barriers and/or facilitators of PCC; none evaluated interventions to improve PCC. While few studies were included, they revealed numerous barriers of PCC at the patient, clinician and organization/system level for immigrants and refugees from a wide range of countries of origin. Studies also reported facilitators of PCC, though largely at the clinician level; thus, patient and organization/system level facilitators of PCC for immigrants and refugees are not fully known. Barriers are facilitators were similar by type of migrant (refugees versus immigrants), care (general/primary, mental health, maternity), and research design (qualitative versus quantitative). Only 5 studies pertained to women, and addressed family planning or maternal care. No additional studies reported results by sex/gender. Thus few barriers or facilitators specific to PCC for immigrant or refugee women emerged. Mapping of facilitators to a PCC framework identified specific PCC domains for which knowledge of strategies to achieve PCC for migrants is lacking, particularly women migrants.

This study confirms prior research on factors that influence PCC for migrants. A scoping review (27 studies, 1993–2014) of studies based in Canada involving immigrants from various ethnic origins found that quality of primary care was influenced by patient-specific factors including culture (i.e. social stigma of disease, disrespectful to address elders by first name), communication (i.e. language skills, print information not regarded as reliable) and socioeconomic (i.e. unable to attend appointments due to multiple jobs or shift work) factors [7]. An integrative literature review (35 studies, 1997–2015) on cultural competence in cancer management identified clinician-specific factors such as skills, awareness, knowledge, and personal characteristics influenced patient-provider communication [42]. Our findings are unique from other research because we identified a greater number of determinants of high quality care for migrants; by categorizing them, we distinguished patient, clinician and organization/system level determinants, which enables targeted quality improvement efforts; by employing gender sub-analyses, we revealed aspects of care important to women migrants; and by employing a PCC lens using a framework of elements considered ideal by patients and clinicians [20], we revealed a range of approaches and processes that can be employed to improve PCC for migrants, and in particular, women migrants. Thus our study contributes many novel findings to the existing literature.

The findings, including barriers, facilitators and identified gaps in knowledge, give rise to several implications. For example, although immigrants and refugees may have differing healthcare issues and access to health services [2], this study found that immigrants and refugees articulated similar facilitators and barriers of PCC. This may suggest that strategies to implement PCC may be equally beneficial to both groups; however, given that only one study of immigrants explored barriers, further research is needed to more thoroughly compare facilitators and barriers of PCC experienced by immigrants and refugees, and whether those differ by healthcare issue, and warrant different strategies to implement PCC. Language emerged in this review as a key barrier of PCC for immigrants and refugees, and access to or the use of interpreters was the corresponding facilitator. However, the participants of included studies, both patients and clinicians, differed in preference for trained interpreters versus family interpreters, revealing pros and cons to each. As a key barrier, further research must assess strategies or interventions for overcoming language-based challenges, and likely both options are needed. In the case where trained interpreters are not available or not preferred by patients, family interpreters must be used, and research should explore how to prepare family members for this role. In the case where trained interpreters are available, but not used either because clinicians perceive them to be time-consuming or inaccurate, or because clinicians lack knowledge or skill in how to use trained interpreters, research should explore the skills and processes essential needed by interpreters to facilitate discussions with migrants, and how to train clinicians to use trained interpreters. The views and experiences of medical interpreters should also be considered [43].

This review also revealed tension or challenges in respecting and accommodating culture without stereotyping patients according to ethnicity, religion or country of origin, and without compromising medical care. A key clinician-level barrier in this study was lack of training or professional development on how to deliver culturally competent care. A Cochrane systematic review on cultural competence education for healthcare professionals (5 randomized controlled trials involving 337 clinicians and 8400 patients reflecting a variety of cultures/languages published from 1991 to 2010) found no effect on patient satisfaction with consultations, patient scores of physician cultural competency, or treatment outcomes, but patient adherence to prevention or treatment improved in the intervention group [44]. Given few studies and mixed results of the Cochrane review [44], further research is needed on how to equip clinicians to achieve PCC for immigrants or refugees, and by specific condition, as PCC may vary across health care issues.

Few studies focused on women, thus few barriers or facilitators of PCC specific to immigrant or refugee women emerged. Those that did pertained to family planning or maternity care. However, women in general experience disparities in quality of care for many health care issues across the lifespan including depression and cardiovascular disease [45, 46]. To address the WHO Global Action Plan’s call to improve the health and well-being of migrant women, further research is needed on determinants of, and interventions to support PCC for immigrant and refugee women [2]. Such research could inform the development of clinical practice guidelines, noted in this review as an organization/system level strategy that could help clinicians tailor care for immigrant and refugee women. In prior reviews, we also found a lack of conceptual guidance and research on what constitutes PCC for women in general [47, 48], and that guidelines lacked information on PCC or women’s health [49].

The strengths of this study included use of rigorous scoping review methods [22, 23], compliance with standards for the conduct and reporting of reviews [24] and use of a framework PCC to characterize facilitators and barriers [20]. Several issues may limit the interpretation and application of the findings. Despite having conducted a comprehensive search of multiple databases that complied with standards for search strategies [25] it was limited to English language studies. We did not search the grey literature given the methodological challenges that have been identified by others [50, 51]. The search strategy may not have identified all relevant studies or our screening criteria may have been too stringent. Few studies were eligible and those studies provided few specific details about PCC strategies or interventions. Risk of bias of included studies was not assessed as this is not customary for a scoping review [22, 23]. Although scoping reviews often include consultation with stakeholders to interpret the findings [22, 23], this step was not done because studies were few, and this study was one part of a larger investigation that has yet to be completed. Most studies addressed migrants in general and addressed multiple cultures from 24+ countries, so the findings appear to be transferrable. However, studies did not report findings by culture and the variety of cultures differed by study, so we lack insight on whether and how barriers and facilitators differ across groups that differ by culture, country of origin or religion.

Conclusion

While few studies were included, we identified numerous determinants of high quality care for migrants; distinguished patient, clinician and organization/system level determinants; revealed aspects of care important to women migrants; and outlined a range of approaches and processes that can be employed to improve PCC for migrants from 24+ countries of origin, and in particular, women migrants. Barriers are facilitators were similar by type of migrant (refugees versus immigrants), care (general/primary, mental health, maternity), and research design (qualitative versus quantitative). Still, the few facilitators identified pertained largely to 2 PCC domains, thereby identifying gaps in knowledge of how to achieve PCC in 4 domains. As only 5 studies focused on migrant women, and no other studies reported sub-analyses by gender, we revealed a paucity of knowledge on how to achieve PCC for migrant women. Also, studies did not report findings by culture. Thus, further research is needed on determinants of, and interventions to support PCC for migrants that differ by culture, country of origin or religion, and particularly for migrant women.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Abbreviations

- PCC:

-

Patient-centred care

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- PRISMA-Scr:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis criteria for scoping reviews

- PICO:

-

Population, Issues, Comparisons and Outcomes framework

References

Segal UA. Globalization, migration, and ethnicity. Public Health. 2019;172:135–42.

World Health Organization. Global action plan, 2019-2023: Promoting the health of refugees and migrants, vol. 2019. New York: WHO Press. https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA72/A72_25-en.pdf. Accessed January 2, 2019.

Wylie L, Van Meyel R, Harder H, et al. Assessing trauma in a transcultural context: challenges in mental health care with immigrants and refugees. Public Health Rev. 2018;39:22.

Pitkin Derose K, Bahney BW, Escarce JJ. Immigrants and health care access, quality, and cost. Med Care. 2009;66:355–408.

Suurmond J, Uiters E, De Bruijne MC, et al. Negative health care experiences of immigrants: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:10.

Clough J, Lee S, Chae DH. Barriers to health care among Asian immigrants in the United States: a traditional review. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24:384–403.

Ahmed S, Shommu NS, Rumana N, et al. Barriers to access of primary healthcare by immigrant populations in Canada: a literature review. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016;18:1522–40.

Hiam L, Gionakis N, Holmes SM, et al. Overcoming the barriers migrants face in accessing health care. Public Health. 2019;172:89–92.

Diaz E, Ortiz-Barreda G, Ben-Schlomo Y, et al. Interventions to improve immigrant health. A scoping review. Eur J Pub Health. 2017;27:433–9.

World Health Organization. Fourth World Conference on Women. Geneva: WHO Press; 1995.

World Health Organization. Women and Health. Geneva: WHO Press; 2009.

United Nations. Gender equality in the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York: UN Women; 2018.

Adunlin G, Cyrus JW, Asare M, et al. Barriers and facilitators to breast and cervical cancer screening among immigrants in the United States. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019;21:606–58.

Higginbottom GM, Morgan M, Alexandre M, et al. Immigrant women’s experiences of maternity-care services in Canada: a systematic review using a narrative synthesis. Syst Rev. 2015;4:13.

Coleman-Minahan K, Potter JE. Quality of postpartum contraceptive counseling and changes in contraceptive method preferences. Contraception. 2019;100:492–7.

Stanzel KA, Hammarberg K, Fisher J. Experiences of menopause, self-management strategies for menopausal symptoms and perceptions of health care among immigrant women: a systematic review. Climacteric. 2018;21:101–10.

Januwalla A, Pulver A, Wanigaratne S, et al. Interventions to reduce adverse health outcomes resulting from manifestations of gender bias amongst immigrant populations: a scoping review. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18:104.

Saha S, Beach MC, Cooper LA. Patient centeredness, cultural competence and healthcare quality. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(11):1275–85.

Shen Z. Cultural competence models and cultural competence assessment instruments in nursing: a literature review. J Transcult Nurs. 2015;62:308–21.

McCormack LA, Treiman K, Rupert D, et al. Measuring patient-centered communication in cancer care: a literature review and the development of a systematic approach. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:1085–9.

Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3:1–18.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32.

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18:143.

Tricco A, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73.

McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, et al. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–6.

Harding C, Seal A, Duncan G, et al. General practitioner and registrar involvement in refugee health: exploring needs and perceptions. Aust Health Rev. 2019;43:92–7.

Winn A, Hetherington E, Tough S. Caring for pregnant refugee women in a turbulent policy landscape: perspectives of health care professionals in Calgary, Alberta. Int J Equity Health. 2018;17:91.

Mollah TN, Antoniades J, Lafeer FI, et al. How do mental health practitioners operationalise cultural competency in everyday practice? A qualitative analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):480.

Murray L, Elmer S, Elkhair J. Perceived barriers to managing medications and solutions to barriers suggested by Bhutanese former refugees and service providers. J Transcult Nurs. 2018;29:570–7.

Hjörleifsson S, Hammer E, Díaz E. General practitioners’ strategies in consultations with immigrants in Norway – practice-based shared reflections among participants in focus groups. Fam Pract. 2018;35:216–21.

Jones SM. Trust development with the Spanish-speaking Mexican American patient: a grounded theory study. West J Nurs Res. 2018;40:799–814.

Mohammadi S, Carlbom A, Taheripanah R, et al. Experiences of inequitable care among afghan mothers surviving near-miss morbidity in Tehran, Iran: a qualitative interview study. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16:121.

Paternotte E, van Dulmen S, L B, et al. Intercultural communication through the eyes of patients: experiences and preferences. Int J Med Educ. 2017;16:170–5.

Larsson EC, Fried S, Essén B, et al. Equitable abortion care - a challenge for health care providers. Experiences from abortion care encounters with immigrant women in Stockholm, Sweden. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2016;10:14–8.

Paternotte E, Scheele F, van Rossum TR, et al. How do medical specialists value their own intercultural communication behaviour? A reflective practice study. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:222.

Phillippi JC, Holley SL, Payne K, et al. Facilitators of prenatal care in an exemplar urban clinic. Women Birth. 2016;29:160–7.

Clochesy JM, Gittner LS, Hickman RL, et al. Wait, Won’t! Want: barriers to health care as perceived by medically and socially disenfranchised communities. J Health Hum Serv Adm. 2015;38:174–214.

De Jesus M, Earl TR. Perspectives on quality mental health care from Brazilian and cape Verdean outpatients: implications for effective patient-centered policies and models of care. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2014;21:9.

Papic O, Malak Z, Rosenberg E. Survey of family physicians’ perspectives on management of immigrant patients: attitudes, barriers, strategies, and training needs. Pat Educ Counsel. 2012;86:205–9.

Hasnain M, Connell KJ, Menon U, et al. Patient-centered care for Muslim women: provider and patient perspectives. J Women's Health. 2011;20:73–83.

Lo MC. Cultural brokerage: creating linkages between voices of lifeworld and medicine in cross-cultural clinical settings. Health (London). 2010;14:484–504.

Brown O, Ham-Baloyi WT, van Rooyen DRM, et al. Culturally competent provider communication in the management of cancer: an integrative literature review. Glob Health Action. 2016;9:33208.

Hudelson P. Improving patient-provider communication: insights from interpreters. Fam Pract. 2005;22:311–6.

Horvat L, Horey D, Romiso P, Kis-Rigo J. Cultural competence education for health professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;5:CD009405.

Gagné S, Vasiliadis HM, Préville M. Gender differences in general and specialty outpatient mental health service use for depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:135.

O’Brien C, Valsdottir L, Wasfy JH, et al. Comparison of 30-day readmission rates after hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction in men versus women. Am J Cardiol. 2017;120:1070–6.

Ramlakhan JU, Foster AM, Grace SL, et al. What constitutes patient-centred care for women: a theoretical rapid review. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18:182.

Gagliardi AR, Nyhof BB, Dunn S, et al. How is patient-centred care conceptualized in women's health: a scoping review. BMC Womens Health. 2019;19:156.

Gagliardi AR, Green C, Dunn S, et al. How do and could clinical guidelines support patient-centred care for women: content analysis of guidelines. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0224507.

Benzies KM, Premji S, Hayden KA, et al. State-of-the-evidence reviews: advantages and challenges of including grey literature. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2006;3:55–61.

Adams J, Hillier-Brown FC, Moore HJ, et al. Searching and synthesising ‘grey literature’ and ‘grey information’ in public health: critical reflections on three case studies. Syst Rev. 2016;5:164.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (grant 251). The funder had no role in design of the study; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; or in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ARG conceptualized the research, acquired funding, coordinated the study, analyzed data, and edited the manuscript. TF and BJ collected and analyzed data, and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Data were publicly available and not acquired from human subjects so ethics approval was not required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Search strategy. Strategy used to search databases for relevant studies.

Additional file 2.

Data extracted from included studies. Table of data on study characteristics and findings.

Additional file 3.

Comparison of facilitators and barriers by migrant status, type of care and study design.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Filler, T., Jameel, B. & Gagliardi, A.R. Barriers and facilitators of patient centered care for immigrant and refugee women: a scoping review. BMC Public Health 20, 1013 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09159-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09159-6