Abstract

Purpose of Review

β-Cryptoxanthin is one of the most common carotenoids. With high concentrations in human serum and tissue, it is inversely associated with many life-threatening diseases. This paper presents a brief overview of the chemical properties and occurrence of β-cryptoxanthin and summarizes the recent trend in β-cryptoxanthin research.

Recent Findings

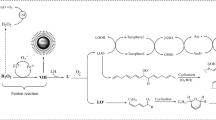

β-Cryptoxanthin is an oxygenated carotenoid common as both free and esterified forms in fruits and vegetables. The distribution of free β-cryptoxanthin and β-cryptoxanthin esters is dependent upon plant types and environmental conditions, such as season, processing techniques, and storage temperatures. The use of β-cryptoxanthin as a nutritional supplement, food additive, and food colorant have stimulated a variety of approaches to identify and quantify free β-cryptoxanthin and β-cryptoxanthin esters. Advances in analytic approaches, including high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with UV and mass spectrometry (MS), have been developed to analyze β-cryptoxanthin, especially the ester forms. In recent years, β-cryptoxanthin has been thought to play an import role in promoting human health, particularly among the population receiving β-cryptoxanthin as a supplement. Some research indicates that the bioavailability of β-cryptoxanthin in typical diets is greater than that of other major carotenoids, suggesting that β-cryptoxanthin-rich foods are probably good sources of carotenoids.

Summary

β-Cryptoxanthin provides various potential benefits for human health. The chemical structure, occurrence, and absorption of β-cryptoxanthin are discussed in this review. This review provides the latest major approaches used to identify and quantify β-cryptoxanthin. Additionally, various benefits, including provitamin A, anti-obesity effects, antioxidant activities, anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer activity, are summarized in this review.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bunea A, Socaciu C, Pintea A. Xanthophyll esters in fruits and vegetables. Not Bot Horti Agrobot Cluj-Napoca. 2014;42:310–24. https://doi.org/10.1583/nbha4229700.

Jaswir I. Carotenoids: sources, medicinal properties and their application in food and nutraceutical industry. J Med Plant Res. 2011;5:7119–31. https://doi.org/10.5897/JMPRX11.011.

Namitha KK, Negi PS. Chemistry and biotechnology of carotenoids. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2010;50:728–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2010.499811.

Kelly EM, Ramkumar S, Sun W, Ortiz CC, Kiser PD, Golczak M, et al. The biochemical basis of vitamin A production from the asymmetric carotenoid β-cryptoxanthin 2018:13:2121–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/acschembio.8b00290.

Mariutti LRB, Mercadante AZ. Carotenoid esters analysis and occurrence: what do we know so far? Arch Biochem Biophys. 2018;648:36–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2018.04.005.

Saini RK, Nile SH, Park SW. Carotenoids from fruits and vegetables: chemistry, analysis, occurrence, bioavailability and biological activities. Food Res Int. 2015;76:735–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2015.07.047.

Zhu CH, Gertz ER, Cai Y, Burri BJ. Consumption of canned citrus fruit meals increases human plasma β-cryptoxanthin concentration, whereas lycopene and β-carotene concentrations did not change in healthy adults. Nutr Res. 2016;36:679–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2016.03.005.

Sugiura M. β-Cryptoxanthin and the risk for lifestyle-related disease: findings from recent nutritional epidemiologic studies. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2015;135:67–76. https://doi.org/10.1248/yakushi.14-00208-5.

Takayanagi K, Mukai K. Beta-cryptoxanthin, a novel carotenoid derived from Satsuma mandarin, prevents abdominal obesity. Nutr Prev Treat Abdom Obes. 2014:381–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407869-7.00034-9.

Burri BJ, La Frano MR, Zhu C. Absorption, metabolism, and functions of β-cryptoxanthin. Nutr Rev. 2016;74:69–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuv064.

Nakamura M, Sugiura M, Ogawa K, Ikoma Y, Yano M. Serum β-cryptoxanthin and β-carotene derived from Satsuma mandarin and brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity: the Mikkabi cohort study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;26:808–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2016.04.001.

Burri BJ. Beta-cryptoxanthin as a source of vitamin A. J Sci Food Agric. 2015;95:1786–94. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.6942.

Mein JR, Dolnikowski GG, Ernst H, Russell RM, Wang XD. Enzymatic formation of apo-carotenoids from the xanthophyll carotenoids lutein, zeaxanthin and β-cryptoxanthin by ferret carotene-9′, 10′-monooxygenase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;506:109–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2010.11.005.

Iskandar AR, Miao B, Li X, Hu KQ, Liu C, Wang XD. Cancer Prev Res. 2016;9(β-Cryptoxanthin reduced lung tumor multiplicity and inhibited lung cancer cell motility by downregulating nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α7 signaling):875–86. https://doi.org/10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-16-0161.

Montonen J, Knekt P, Järvinen R, Reunanen A. Dietary antioxidant intake and risk of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:362–6. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.27.2.362.

Pattison DJ, Symmons DPM, Lunt M, Welch A, Bingham SA, Day NE, et al. Dietary beta-cryptoxanthin and inflammatory polyarthritis: results from a population-based prospective study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:451–5 doi:82/2/451.

Yilmaz B, Sahin K, Bilen H, Bahcecioglu IH, Bilir B, Ashraf S, et al. Carotenoids and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2015;4:161–71. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2304-3881.2015.01.11.

Sugiura M, Nakamura M, Ogawa K, Ikoma Y, Yano M. High vitamin C intake with high serum β-cryptoxanthin associated with lower risk for osteoporosis in post-menopausal Japanese female subjects: Mikkabi cohort study. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol. 2016;62:185–91. https://doi.org/10.3177/jnsv.62.185.

Park G, Horie T, Iezaki T, Okamoto M, Fukasawa K, Kanayama T, et al. Daily oral intake of β-cryptoxanthin ameliorates neuropathic pain. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2017;81:1014–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/09168451.2017.1280661.

Nishi K, Muranaka A, Nishimoto S, Kadota A, Sugahara T. Immunostimulatory effect of β-cryptoxanthin in vitro and in vivo. J Funct Foods. 2012;4:618–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2012.04.001.

Granado-Lorencio F, Donoso-Navarro E, Sánchez-Siles LM, Blanco-Navarro I, Pérez-Sacristán B. Bioavailability of β-cryptoxanthin in the presence of phytosterols: in vitro and in vivo studies. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:11819–24. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf202628w.

Hornero-Méndez D, Cerrillo I, Ortega Á, Rodríguez-Griñolo MR, Escudero-López B, Martín F, et al. β-Cryptoxanthin is more bioavailable in humans from fermented orange juice than from orange juice. Food Chem. 2018;262:215–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.04.083.

Schlatterer J, Breithaupt DE, Wolters M, Hahn A. Plasma responses in human subjects after ingestions of multiple doses of natural a-cryptoxanthin: a pilot study 2006. 96, 371, https://doi.org/10.1079/BJN20061848.

Schlatterer J, Breithaupt DE. Cryptoxanthin structural isomers in oranges, orange juice, and other fruits. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:6355–61. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf050362w.

Ma G, Zhang L, Iida K, Madono Y, Yungyuen W, Yahata M, et al. Identification and quantitative analysis of β-cryptoxanthin and β-citraurin esters in Satsuma mandarin fruit during the ripening process. Food Chem. 2017;234:356–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.05.015.

Ríos JJ, Xavier AAO, Díaz-Salido E, Arenilla-Vélez I, Jarén-Galán M, Garrido-Fernández J, et al. Xanthophyll esters are found in human colostrum. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2017;61. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201700296.

Fu HF, Xie BJ, Fan G, Ma SJ, Zhu XR, Pan SY. Effect of esterification with fatty acid of β-cryptoxanthin on its thermal stability and antioxidant activity by chemiluminescence method. Food Chem. 2010;122:602–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.03.019.

Thomas N. Pigments from microalgae: a new perspective with emphasis on phycocyanin. 7th Int Congr Pigment Food Realizz a Cura Di Booksystem Srl. 2013:349–52.

Pintea A, Ă DŃR, Bunea A, Andrei S. Impact of esterification on the antioxidant capacity of β-cryptoxanthin. Bull UASVM Anim Sci Biotechnol 2013:70:79–85.

Sugiura M, Ogawa K, Yano M. Comparison of bioavailability between β-cryptoxanthin and β-carotene and tissue distribution in its intact form in rats. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2014;78:307–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/09168451.2014.878220.

Mapelli-Brahm P, Corte-Real J, Meléndez-Martínez AJ, Bohn T. Bioaccessibility of phytoene and phytofluene is superior to other carotenoids from selected fruit and vegetable juices. Food Chem. 2017;229:304–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.02.074.

Burri BJ, Chang JST, Neidlinger TR. β-Cryptoxanthin- and α-carotene-rich foods have greater apparent bioavailability than β-carotene-rich foods in Western diets. Br J Nutr. 2011;105:212–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114510003260.

Schweiggert RM, Vargas E, Conrad J, Hempel J, Gras CC, Ziegler JU, et al. Carotenoids, carotenoid esters, and anthocyanins of yellow-, orange-, and red-peeled cashew apples (Anacardium occidentale L.). Food Chem. 2016;200:274–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.01.038.

Breithaupt DE, Bamedi A. Carotenoid esters in vegetables and fruits: a screening with emphasis on β-cryptoxanthin esters. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:2064–70. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf001276t.

Sumiasih IH, Poerwanto R, Efendi D, Agusta A, Yuliani S. The analysis of β-cryptoxanthin and zeaxanthin using HPLC in the accumulation of orange color on lowland citrus. Int J Appl Biol. 2017;1:37–45. https://doi.org/10.30597/IJAB.V1I2.3066.

Sarungallo ZL, Hariyadi P, Andarwulan N, Purnomo EH, Wada M. Analysis of α-cryptoxanthin, β-cryptoxanthin, α-carotene, and β-carotene of pandanus conoideus oil by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Procedia Food Sci. 2015;3:231–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profoo.2015.01.026.

Mercadante AZ, Rodrigues DB, Petry FC, Mariutti LRB. Carotenoid esters in foods—a review and practical directions on analysis and occurrence. Food Res Int. 2017;99:830–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2016.12.018.

Collera-Zúñiga O, Garcı́a Jiménez F, Meléndez Gordillo R. Comparative study of carotenoid composition in three mexican varieties of Capsicum annuum L. Food Chem 2005:90:109–114. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FOODCHEM.2004.03.032.

Donato P, Giuffrida D, Oteri M, Inferrera V, Dugo P, Mondello L. Supercritical fluid chromatography × ultra-high pressure liquid chromatography for red chilli pepper fingerprinting by photodiode array, quadrupole-time-of-flight and ion mobility mass spectrometry (SFC × RP-UHPLC-PDA-Q-ToF MS-IMS). Food Anal Methods. 2018;11:3331–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12161-018-1307-x.

Panfili G, Alessandra Fratianni A, Irano M. Improved normal-phase high-performance liquid chromatography procedure for the determination of carotenoids in cereals 2004; 52:6373, 6377. https://doi.org/10.1021/JF0402025.

Hao Z, Parker B, Knapp M, Yu L (Lucy). Simultaneous quantification of α-tocopherol and four major carotenoids in botanical materials by normal phase liquid chromatography–atmospheric pressure chemical ionization-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A 2005:1094:83–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHROMA.2005.07.097.

Rivera SM, Canela-Garayoa R. Analytical tools for the analysis of carotenoids in diverse materials. J Chromatogr A. 2012;1224:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2011.12.025.

Giuffrida D, Donato P, Dugo P, Mondello L. Recent analytical techniques advances in the carotenoids and their derivatives determination in various matrixes. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66:3302–7. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.8b00309.

Petry FC, Mercadante AZ. Composition by LC-MS/MS of new carotenoid esters in mango and citrus. J Agric Food Chem. 2016;64:8207–24. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.6b03226.

Cacciola F, Giuffrida D, Utczas M, Mangraviti D, Dugo P, Menchaca D, et al. Application of comprehensive two-dimensional liquid chromatography for carotenoid analysis in red Mamey (Pouteria sapote) fruit. Food Anal Methods. 2016;9:2335–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12161-016-0416-7.

Dugo P, Herrero M, Giuffrida D, Kumm T, Dugo G, Mondello L. Application of comprehensive two-dimensional liquid chromatography to elucidate the native carotenoid composition in red orange essential oil. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:3478–85. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf800144v.

Cacciola F, Donato P, Giuffrida D, Torre G, Dugo P, Mondello L. Ultra high pressure in the second dimension of a comprehensive two-dimensional liquid chromatographic system for carotenoid separation in red chili peppers. J Chromatogr A. 2012;1255:244–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2012.06.076.

Kurz C, Carle R, Schieber A. HPLC-DAD-MSn characterisation of carotenoids from apricots and pumpkins for the evaluation of fruit product authenticity. Food Chem. 2008;110:522–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.02.022.

Schweiggert RM, Steingass CB, Esquivel P, Carle R. Chemical and morphological characterization of Costa Rican papaya (Carica papaya L.) hybrids and lines with particular focus on their genuine carotenoid profiles. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:2577–85. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf2045069.

Giuffrida D, La Torre L, Manuela S, Pellicanò TM, Dugo G. Application of HPLC-APCI-MS with a C-30 reversed phase column for the characterization of carotenoid esters in mandarin essential oil. Flavour Fragr J. 2006;21:319–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/ffj.1601.

Giuffrida D, Dugo P, Salvo A, Saitta M, Dugo G. Free carotenoid and carotenoid ester composition in native orange juices of different varieties. Fruits. 2010;65:277–84. https://doi.org/10.1051/fruits/2010023.

Giuffrida D, Torre G, Dugo P, Dugo G. Determination of the carotenoid profile in peach fruits, juice and jam. Fruits. 2013;68:39–44. https://doi.org/10.1051/fruits/2012049.

Pop RM, Weesepoel Y, Socaciu C, Pintea A, Vincken J-P, Gruppen H. Carotenoid composition of berries and leaves from six Romanian sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) varieties. Food Chem. 2014;147:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.09.083.

Giuffrida D, Dugo P, Torre G, Bignardi C, Cavazza A, Corradini C, et al. Characterization of 12 Capsicum varieties by evaluation of their carotenoid profile and pungency determination. Food Chem. 2013;140:794–802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.09.060.

Murillo E, Giuffrida D, Menchaca D, Dugo P, Torre G, Meléndez-Martinez AJ, et al. Native carotenoids composition of some tropical fruits. Food Chem. 2013;140:825–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.11.014.

Mertz C, Brat P, Caris-Veyrat C, Gunata Z. Characterization and thermal lability of carotenoids and vitamin C of tamarillo fruit (Solanum betaceum Cav.). Food Chem. 2010;119:653–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.07.009.

Inbaraj BS, Lu H, Hung CF, Wu WB, Lin CL, Chen BH. Determination of carotenoids and their esters in fruits of Lycium barbarum Linnaeus by HPLC-DAD-APCI-MS. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2008;47:812–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2008.04.001.

Yoo KM, Moon BK. Comparative carotenoid compositions during maturation and their antioxidative capacities of three citrus varieties. Food Chem. 2016;196:544–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.09.079.

Delgado-Pelayo R, Hornero-Méndez D. Identification and quantitative analysis of carotenoids and their esters from sarsaparilla (Smilax aspera L.) berries. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:8225–32. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf302719g.

Wada Y, Matsubara A, Uchikata T, Iwasaki Y, Morimoto S, Kan K, et al. Investigation of β-cryptoxanthin fatty acid ester compositions in citrus fruits cultivated in Japan. Food Nutr Sci. 2013;04:98–104. https://doi.org/10.4236/fns.2013.49A1016.

Breithaupt DE, Yahia EM, Valdés Velázquez FJ. Comparison of the absorption efficiency of a-and β-cryptoxanthin in female Wistar rats 2007; , 97: 329. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114507336751.

Pérez-Gálvez A, Mínguez-Mosquera MI. Esterification of xanthophylls and its effect on chemical behavior and bioavailability of carotenoids in the human. Nutr Res. 2005;25:631–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NUTRES.2005.07.002.

Wei X, Chen C, Yu Q, Gady A, Yu Y, Liang G, et al. Comparison of carotenoid accumulation and biosynthetic gene expression between Valencia and Rohde Red Valencia sweet oranges. Plant Sci. 2014;227:28–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2014.06.016.

Ma G, Zhang L, Kato M, Yamawaki K, Kiriiwa Y, Yahata M, et al. Effect of blue and red LED light irradiation on β-cryptoxanthin accumulation in the flavedo of citrus fruits. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:197–201. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf203364m.

Venado RE, Owens BF, Ortiz D, Lawson T, Mateos-Hernandez M, Ferruzzi MG, et al. Genetic analysis of provitamin A carotenoid β-cryptoxanthin concentration and relationship with other carotenoids in maize grain (Zea mays L.). Mol Breed. 2017;37:127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11032-017-0723-8.

Ma G, Zhang L, Matsuta A, Matsutani K, Yamawaki K, Yahata M, et al. Enzymatic formation of β-citraurin from β-cryptoxanthin and zeaxanthin by carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase4 in the flavedo of citrus fruit. Plant Physiol. 2013;163:682–95. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.113.223297.

Sumiasih IH, Poerwanto R, Efendi D, Agusta A, Yuliani S. β-cryptoxanthin and zeaxanthin pigments accumulation to induce orange color on citrus fruits. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2018;299:012074. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/299/1/012074.

Khoo HE, Prasad KN, Kong KW, Jiang Y, Ismail A. Carotenoids and their isomers: color pigments in fruits and vegetables. Molecules. 2011;16:1710–38. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules16021710.

Dhuique-Mayer C, Borel P, Reboul E, Caporiccio B, Besancon P, Amiot MJ. β-Cryptoxanthin from citrus juices: assessment of bioaccessibility using an in vitro digestion/Caco-2 cell culture model. Br J Nutr. 2007;97:883–90. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114507670822.

Takayanagi K, Morimoto SI, Shirakura Y, Mukai K, Sugiyama T, Tokuji Y, et al. Mechanism of visceral fat reduction in Tsumura Suzuki obese, diabetes (TSOD) mice orally administered β-cryptoxanthin from Satsuma mandarin oranges (Citrus unshiu Marc). J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:12342–51. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf202821u.

Zheng YF, Bae SH, Kwon MJ, Park JB, Choi HD, Shin WG, et al. Inhibitory effects of astaxanthin, β-cryptoxanthin, canthaxanthin, lutein, and zeaxanthin on cytochrome P450 enzyme activities. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;59:78–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2013.04.053.

Heying EK, Tanumihardjo JP, Vasic V, Cook M, Palacios-Rojas N, Tanumihardjo SA. Biofortified orange maize enhances β-Cryptoxanthin concentrations in egg yolks of laying hens better than tangerine peel fortificant. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62:11892–900. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf5037195.

Breithaupt DE, Weller P, Wolters M, Hahn A. Plasma response to a single dose of dietary β-cryptoxanthin esters from papaya (Carica papaya L.) or non-esterified β-cryptoxanthin in adult human subjects: a comparative study. Br J Nutr. 2003;90:795. https://doi.org/10.1079/BJN2003962.

Wingerath T, Stahl W, Sies H. β-Cryptoxanthin selectively increases in human chylomicrons upon ingestion of tangerine concentrate rich in β-cryptoxanthin esters. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;324:385–90. https://doi.org/10.1006/abbi.1995.0052.

Kotake-Nara E, Nagao A, Kotake-Nara E, Nagao A. Absorption and metabolism of xanthophylls. Mar Drugs. 2011;9:1024–37. https://doi.org/10.3390/md9061024.

La Frano MR, Zhu C, Burri BJ. Assessment of tissue distribution and concentration of b-cryptoxanthin in response to varying amounts of dietary b-cryptoxanthin in the Mongolian gerbil. Br J Nutr. 2014;111:968–78. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114513003371.

Saini RK, Keum YS. Significance of genetic, environmental, and pre- and postharvest factors affecting carotenoid contents in crops: a review. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66:5310–25. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.8b01613.

Gence L, Servent A, Poucheret P, Hiol A, Dhuique-Mayer C. Pectin structure and particle size modify carotenoid bioaccessibility and uptake by Caco-2 cells in citrus juices: vs. concentrates. Food Funct. 2018;9:3523–31. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8fo00111a.

Rodriguez-Amaya D, Kimura M. Harvest plus handbook for carotenoid analysis. Harvest Tech Monogr. 2004;59.

Goto T, Kim YI, Takahashi N, Kawada T. Natural compounds regulate energy metabolism by the modulating the activity of lipid-sensing nuclear receptors. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2013;57:20–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201200522.

Ohshima M, Sugiura M, Ueda K. Effects of β-cryptoxanthin-fortified Satsuma mandarin (Citrus unshiu Marc.) juice on liver function and the serum lipid profile. Nippon Shokuhin Kagaku Kogaku Kaishi. 2010;57:114–20. https://doi.org/10.3136/nskkk.57.114.

Iwata A, Matsubara S, Miyazaki K. Beneficial effects of a beta-cryptoxanthin-containing beverage on body mass index and visceral fat in pre-obese men: double-blind, placebo-controlled parallel trials. J Funct Foods. 2018;41:250–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2017.12.040.

Tsuchida T, Mukai K, Mizuno Y, Masuko K, Minagawa K. The comparative study of beta-cryptoxanthin derived from Satsuma mandarin for fat of human body. Jpn Parmacol Ther. 2008;36:247–53.

Sugiura M, Matsumoto H, Kato M, Ikoma Y, Yano M, Nagao A. Seasonal changes in the relationship between serum concentration of β-cryptoxanthin and serum lipid levels. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2004;50:410–5. https://doi.org/10.3177/jnsv.50.410.

Hirose A, Terauchi M, Hirano M, Akiyoshi M, Owa Y, Kato K, et al. Higher intake of cryptoxanthin is related to low body mass index and body fat in Japanese middle-aged women. Maturitas. 2017;96:89–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.11.008.

Sahin K, Orhan C, Akdemir F, Tuzcu M, Sahin N, Yılmaz I, et al. β-Cryptoxanthin ameliorates metabolic risk factors by regulating NF-κB and Nrf2 pathways in insulin resistance induced by high-fat diet in rodents. Food Chem Toxicol. 2017;107:270–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2017.07.008.

Iwamoto M, Imai K, Ohta H, Shirouchi B, Sato M. Supplementation of highly concentrated β-cryptoxanthin in a Satsuma mandarin beverage improves adipocytokine profiles in obese Japanese women. Lipids Health Dis. 2012;11:52. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-511X-11-52.

Shifakura Y, Takayanagi K, Mukai K, Tanabe H, Inoue M. β-Cryptoxanthin suppresses the adipogenesis of 3T3-L1 cells via RAR activation. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2011;57:426–31. https://doi.org/10.3177/jnsv.57.426.

Hung W-L, Suh JH, Wang Y. Chemistry and health effects of furanocoumarins in grapefruit. J Food Drug Anal. 2017;25:71–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JFDA.2016.11.008.

Yamaguchi M, Uchiyama S. Beta-cryptoxanthin stimulates bone formation and inhibits bone resorption in tissue culture in vitro. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;258:137–44. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:MCBI.0000012848.50541.19.

Granado-Lorencio F, Olmedilla-Alonso B, Herrero-Barbudo C, Blanco-Navarro I, Pérez-Sacristán B. Seasonal variation of serum α- and β-cryptoxanthin and 25-OH-vitamin D3 in women with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:717–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-007-0470-5.

Sugiura M, Nakamura M, Ogawa K, Ikoma Y, Ando F, Shimokata H, et al. Dietary patterns of antioxidant vitamin and carotenoid intake associated with bone mineral density: findings from post-menopausal Japanese female subjects. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:143–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-010-1239-9.

Yamaguchi M. β-Cryptoxanthin and bone metabolism: the preventive role in osteoporosis. J Health Sci. 2008;54:356–69. https://doi.org/10.1248/jhs.54.356.

Uchiyama S, Sumida T, Yamaguchi M. Oral administration of β-cryptoxanthin induces anabolic effects on bone components in the femoral tissues of rats in vivo. Biol Pharm Bull. 2004;27:232–5. https://doi.org/10.1248/bpb.27.232.

Ozaki K, Okamoto M, Fukasawa K, Iezaki T, Onishi Y, Yoneda Y, et al. Daily intake of β-cryptoxanthin prevents bone loss by preferential disturbance of osteoclastic activation in ovariectomized mice. J Pharmacol Sci. 2015;129:72–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphs.2015.08.003.

Sugiura M, Nakamura M, Ogawa K, Ikoma Y, Yano M. High serum carotenoids associated with lower risk for bone loss and osteoporosis in post-menopausal Japanese female subjects: prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52643. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052643.

Yamaguchi M, Igarashi A, Uchiyama S, Sugawara K, Sumida T, Morita S, et al. Effect of beta-crytoxanthin on circulating bone metabolic markers: intake of juice (Citrus unshiu) supplemented with beta-cryptoxanthin has an effect in menopausal women. J Health Sci. 2006;52:758–68. https://doi.org/10.1248/jhs.52.758.

Yamaguchi M. Role of carotenoid β-cryptoxanthin in bone homeostasis. J Biomed Sci. 2012;19:36. https://doi.org/10.1186/1423-0127-19-36.

Yamaguchi M, Igarashi A, Morita S, Sumida T, Sugawara K. Relationship between serum β-cryptoxanthin and circulating bone metabolic markers in healthy individuals with the intake of juice (Citrus unshiu) containing β-Cryptoxanthin. J Health Sci. 2005;51:738–43. https://doi.org/10.1248/jhs.51.738.

Ouchi A, Aizawa K, Iwasaki Y, Inakuma T, Terao J, Nagaoka SI, et al. Kinetic study of the quenching reaction of singlet oxygen by carotenoids and food extracts in solution. Development of a singlet oxygen absorption capacity (SOAC) assay method. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:9967–78. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf101947a.

Pongkan W, Takatori O, Ni Y, Xu L, Nagata N, Chattipakorn SC, et al. β-Cryptoxanthin exerts greater cardioprotective effects on cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury than astaxanthin by attenuating mitochondrial dysfunction in mice. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2017;61:1601077. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201601077.

Park YG, Lee SE, Son YJ, Jeong SG, Shin MY, Kim WJ, et al. Antioxidant β-cryptoxanthin enhances porcine oocyte maturation and subsequent embryo development in vitro. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2018;30:1204–13. https://doi.org/10.1071/RD17444.

Lorenzo Y, Azqueta A, Luna L, Bonilla F, Domínguez G, Collins AR. The carotenoid β-cryptoxanthin stimulates the repair of DNA oxidation damage in addition to acting as an antioxidant in human cells. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:308–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/bgn270.

Haegele AD, Gillette C, O’Neill C, Wolfe P, Heimendinger J, Sedlacek S, et al. Plasma xanthophyll carotenoids correlate inversely with indices of oxidative DNA damage and lipid peroxidation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2000;9:421–5.

Gammone MA, Riccioni G, D’Orazio N. Carotenoids: potential allies of cardiovascular health? Food Nutr Res. 2015;59:26762. https://doi.org/10.3402/fnr.v59.26762.

Ni Y, Nagashimada M, Zhan L, Nagata N, Kobori M, Sugiura M, et al. Prevention and reversal of lipotoxicity-induced hepatic insulin resistance and steatohepatitis in mice by an antioxidant carotenoid, β-cryptoxanthin. Endocrinology. 2015;156:987–99. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2014-1776.

Kobori M, Ni Y, Takahashi Y, Watanabe N, Sugiura M, Ogawa K, et al. β-Cryptoxanthin alleviates diet-induced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis by suppressing inflammatory gene expression in mice. PLoS One, 2014. 9:e98294. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0098294.

Liu C, Bronson RT, Russell RM, Wang XD. β-Cryptoxanthin supplementation prevents cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation, oxidative damage, and squamous metaplasia in ferrets. Cancer Prev Res. 2011;4:1255–66. https://doi.org/10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0384.

Tanaka T, Shnimizu M, Moriwaki H. Cancer chemoprevention by carotenoids. Molecules. 2012;17:3202–42. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules17033202.

Tsushima M, Maoka T, Katsuyama M, Kozuka M, Takao M, Tokuda H, et al. Inhibitory effect of natural carotenoids on Epstein-Barr virus activation activity of a tumor promoter in Raji cells. A screening study for anti-tumor promoters. Biol Pharm Bull. 1995;18:227–33. https://doi.org/10.1248/bpb.18.227.

Bock CH, Ruterbusch JJ, Holowatyj AN, Steck SE, Van Dyke AL, Ho WJ, et al. Renal cell carcinoma risk associated with lower intake of micronutrients. Cancer Med. 2018;7:4087–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.1639.

Bae J-M. Reinterpretation of the results of a pooled analysis of dietary carotenoid intake and breast cancer risk by using the interval collapsing method. Epidemiol Health. 2016;38:e2016024. https://doi.org/10.4178/epih.e2016024.

Leoncini E, Nedovic D, Panic N, Pastorino R, Edefonti V, Boccia S. Carotenoid intake from natural sources and head and neck Cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2015;24:1003–11. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0053.

Tanaka T, Tanaka T, Tanaka M, Kuno T. Cancer chemoprevention by citrus pulp and juices containing high amounts of β-cryptoxanthin and hesperidin. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2012:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/516981.

Tanaka T, Kohno H, Murakami M, Shimada R, Kagami S, Sumida T, et al. Suppression of azoxymethane-induced colon carcinogenesis in male F344 rats by mandarin juices rich in β-cryptoxanthin and hesperidin. Int J Cancer. 2000;88:146–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0215(20001001)88:1<146::AID-IJC23>3.0.CO;2-I.

Millán CS, Soldevilla B, Martín P, Gil-Calderón B, Compte M, Pérez-Sacristán B, et al. β-Cryptoxanthin synergistically enhances the antitumoral activity of oxaliplatin through ΔNP73 negative regulation in colon cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:4398–409. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2027.

Wu C, Han L, Riaz H, Wang S, Cai K, Yang L. The chemopreventive effect of β-cryptoxanthin from mandarin on human stomach cells (BGC-823). Food Chem. 2013;136:1122–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.09.073.

Min K, Min J. Serum carotenoid levels and risk of lung cancer death in US adults. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:736–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.12405.

Yuan JM, Ross RK, Chu XD, Gao YT, Yu MC. Prediagnostic levels of serum beta-cryptoxanthin and retinol predict smoking-related lung cancer risk in Shanghai. China Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:767–73.

Yuan JM, Stram DO, Arakawa K, Lee HP, Yu MC. Dietary cryptoxanthin and reduced risk of lung cancer: the Singapore Chinese health study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2003;12:890–8.

Kohno H, Taima M, Sumida T, Azuma Y, Ogawa H, Tanaka T. Inhibitory effect of mandarin juice rich in β-cryptoxanthin and hesperidin on 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone-induced pulmonary tumorigenesis in mice. Cancer Lett. 2001;174:141–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3835(01)00713-3.

Iskandar AR, Liu C, Smith DE, Hu KQ, Choi SW, Ausman LM, et al. β-cryptoxanthin restores nicotine-reduced lung SIRT1 to normal levels and inhibits nicotine-promoted lung tumorigenesis and emphysema in A/J mice. Cancer Prev Res. 2013;6:309–20. https://doi.org/10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-12-0368.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Natural Products: From Chemistry to Pharmacology

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jiao, Y., Reuss, L. & Wang, Y. β-Cryptoxanthin: Chemistry, Occurrence, and Potential Health Benefits. Curr Pharmacol Rep 5, 20–34 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40495-019-00168-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40495-019-00168-7