Abstract

Background

Inclisiran inhibits hepatic synthesis of proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9 (PCSK9). The comparison of inclisiran with statin versus statin alone in the ORION-10 trial demonstrated significant reductions in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C). Our study explored whether the use of inclisiran with statin versus statin alone for secondary prevention of cardiovascular events is cost effective from the Australian healthcare perspective, based on the price of currently available PCSK9 inhibitors.

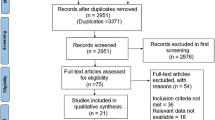

Methods

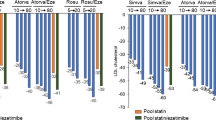

A Markov model was developed based on the ORION-10 trial to model outcomes and costs incurred by patients over a lifetime analysis. The three health states were ‘alive with cardiovascular disease (CVD)’, ‘alive with recurrent CVD’, and ‘dead’. Cost and utilities were estimated from published sources. The cost of inclisiran was estimated from the annual cost of evolocumab, a PCSK9 inhibitor currently available in Australia (AU$6334, based on 2020 data). Outcomes of interest were incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) in terms of cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) and cost per year of life saved (YoLS). All costs, QALYs and YoLS were discounted at 5% per annum in line with Australian standards.

Results

Among 1000 subjects followed-up over a lifetime analysis, inclisiran with statin compared with statin alone prevented 235 non-fatal myocardial infarctions (NFMIs; 151 NFMI and 84 repeat NFMI cases) and 114 coronary revascularisation cases, and increased years of life by 0.549 (discounted) and QALYs by 0.468 (discounted). At an annual price of AU$6334, the net marginal cost was AU$58,965 per person. The above values equated to ICERs of AU$107,402 per YoLS and AU$125,732 per QALY gained. Assuming a willingness-to-pay threshold of AU$50,000, inclisiran would have to be priced 60% lower than other available PCSK9 inhibitors to be considered cost effective.

Conclusions

As an adjunct therapy to statin treatment in those who have persistently elevated LDL-C despite optimal statin therapy, inclisiran is effective in reducing cardiovascular events in patients with atherosclerotic CVD. Inclisiran is not cost effective from the Australian healthcare perspective, assuming acquisition costs of current PCSK9 inhibitors. The cost of inclisiran would have to be 60% lower than that of evolocumab.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ference BA, Ginsberg HN, Graham I, Ray KK, Packard CJ, Bruckert E, et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(32):2459–72. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx144.

Cholesterol Treatment Trialists Collaboration, Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, Holland LE, Reith C, et al. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376(9753):1670–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61350-5.

Koskinas KC, Siontis GCM, Piccolo R, Mavridis D, Raber L, Mach F, et al. Effect of statins and non-statin LDL-lowering medications on cardiovascular outcomes in secondary prevention: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(14):1172–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx566.

Zhang H, Plutzky J, Skentzos S, Morrison F, Mar P, Shubina M, et al. Discontinuation of statins in routine care settings: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(7):526–34. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-7-201304020-00004.

Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, Honarpour N, Wiviott SD, Murphy SA, et al. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(18):1713–22. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1615664.

Evolocumab [database on the internet]. Department of Health Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. https://www.pbs.gov.au/medicine/item/10958R. Accessed 11 June 2020.

Ray KK, Landmesser U, Leiter LA, Kallend D, Dufour R, Karakas M, et al. Inclisiran in patients at high cardiovascular risk with elevated LDL cholesterol. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(15):1430–40. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1615758.

Srivastava K, Arora A, Kataria A, Cappelleri JC, Sadosky A, Peterson AM. Impact of reducing dosing frequency on adherence to oral therapies: a literature review and meta-analysis. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:419–34. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S44646.

von Treskow A, O’Donnell M. Novartis successfully completes acquisition of The Medicines Company, adding a potentially first-in-class, investigational cholesterol-lowering therapy inclisiran. Basel: Novartis; 2020.

Ray KK, Wright RS, Kallend D, Koenig W, Leiter LA, Raal FJ, et al. Two phase 3 trials of inclisiran in patients with elevated LDL cholesterol. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(16):1507–19. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1912387.

Simons LA. An updated review of lipid-modifying therapy. Med J Aust. 2019;211(2):87–92. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.50142.

Briggs A, Sculpher M. An introduction to Markov modelling for economic evaluation. Pharmacoeconomics. 1998;13(4):397–409. https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-199813040-00003.

Caro JJ, Briggs AH, Siebert U, Kuntz KM. Force I-SMGRPT. Modeling good research practices—overview: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force-1. Value Health. 2012;15(6):796–803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2012.06.012.

Guidelines for preparing submissions to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC). Department of Health. https://pbac.pbs.gov.au/. Accessed 17 Mar 2020.

Taylor C, Jan S. Economic evaluation of medicines. Aust Prescr. 2017;40(2):76–8. https://doi.org/10.18773/austprescr.2017.014.

Briggs A, Claxton B, Sculpher M. Decision modelling for health economic evaluation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006.

Thune JJ, Signorovitch JE, Kober L, McMurray JJ, Swedberg K, Rouleau J, et al. Predictors and prognostic impact of recurrent myocardial infarction in patients with left ventricular dysfunction, heart failure, or both following a first myocardial infarction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13(2):148–53. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjhf/hfq194.

Wilson PW, D’Agostino R Sr, Bhatt DL, Eagle K, Pencina MJ, Smith SC, et al. An international model to predict recurrent cardiovascular disease. Am J Med. 2012;125(7):695–703.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.01.014.

Yudi MB, Clark DJ, Farouque O, Andrianopoulos N, Ajani AE, Brennan A, et al. Trends and predictors of recurrent acute coronary syndrome hospitalizations and unplanned revascularization after index acute myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J. 2019;212:134–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2019.02.013.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. General Record of Incidence of Mortality (GRIM) data. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2019.

Ademi Z, Ofori-Asenso R, Zomer E, Owen A, Liew D. The cost-effectiveness of icosapent ethyl in combination with statin therapy compared with statin alone for cardiovascular risk reduction. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487319896648.

National Hospital Cost Data Collection Report; Public Sector, Round 22 (Financial Year 2017–18). Independent Hospital Pricing Authority; 2020.

Perera K, Ademi Z, Liew D, Zomer E. Sacubitril-valsartan versus enalapril for acute decompensated heart failure: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487319878953.

Zomer E, Liew D, Tonkin A, Trauer JM, Ademi Z. The cost-effectiveness of canakinumab for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: the Australian healthcare perspective. Int J Cardiol. 2019;285:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.01.037.

Health expenditure Australia 2017–18. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2019.

Cobiac LJ, Magnus A, Barendregt JJ, Carter R, Vos T. Improving the cost-effectiveness of cardiovascular disease prevention in Australia: a modelling study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:398. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-398.

PBS Expenditure and Prescriptions Report 1 July 2018 to 30 June 2019. PBS; 2019. https://www.pbs.gov.au/info/statistics/expenditure-prescriptions/pbs-expenditure-and-prescriptions-report.

Lewis EF, Li Y, Pfeffer MA, Solomon SD, Weinfurt KP, Velazquez EJ, et al. Impact of cardiovascular events on change in quality of life and utilities in patients after myocardial infarction: a VALIANT study (valsartan in acute myocardial infarction). JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2(2):159–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2013.12.003.

Lindgren P, Kahan T, Poulter N, Buxton M, Svarvar P, Dahlof B, et al. Utility loss and indirect costs following cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients: the ASCOT health economic substudy. Eur J Health Econ. 2007;8(1):25–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-006-0002-9.

van Stel HF, Busschbach JJ, Hunink MG, Buskens E. Impact of secondary cardiovascular events on health status. Value Health. 2012;15(1):175–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2011.09.004.

Guide to the Methods of Technology Appraisal Report. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2013.

Wijeysundera HC, Farshchi-Zarabi S, Witteman W, Bennell MC. Conversion of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire into EQ-5D utilities for ischemic heart disease: a systematic review and catalog of the literature. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2014;6:253–68. https://doi.org/10.2147/CEOR.S63187.

Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, Carswell C, Moher D, Greenberg D, et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement. Pharmacoeconomics. 2013;31(5):361–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-013-0032-y.

Korman MJ, Retterstol K, Kristiansen IS, Wisloff T. Are PCSK9 inhibitors cost effective? Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(9):1031–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-018-0671-0.

Edney LC, Haji Ali Afzali H, Cheng TC, Karnon J. Estimating the reference incremental cost-effectiveness ratio for the australian health system. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(2):239–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-017-0585-2.

ClinicalTrials.gov. Trial to Assess the effect of long term dosing of inclisiran in subjects with high CV risk and elevated LDL-C (ORION-8). Bethesda. ClinicalTrials.gov 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03814187. Accessed 19 May 2020.

Coleman CI, Limone B, Sobieraj DM, Lee S, Roberts MS, Kaur R, et al. Dosing frequency and medication adherence in chronic disease. J Manag Care Pharm. 2012;18(7):527–39. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2012.18.7.527.

Choudhry NK, Fischer MA, Avorn J, Liberman JN, Schneeweiss S, Pakes J, et al. The implications of therapeutic complexity on adherence to cardiovascular medications. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(9):814–22. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2010.495.

Kosmas CE, Silverio D, Ovalle J, Montan PD, Guzman E. Patient adherence, compliance, and perspectives on evolocumab for the management of resistant hypercholesterolemia. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:2263–6. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S149423.

Cutler RL, Fernandez-Llimos F, Frommer M, Benrimoj C, Garcia-Cardenas V. Economic impact of medication non-adherence by disease groups: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2018;8(1):e016982. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016982.

Sheridan C. PCSK9-gene-silencing, cholesterol-lowering drug impresses. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37(12):1385–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0351-4.

Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, McCagg A, White JA, Theroux P, et al. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(25):2387–97. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1410489.

Murphy SA, Pedersen TR, Gaciong ZA, Ceska R, Ezhov MV, Connolly DL, et al. Effect of the PCSK9 inhibitor evolocumab on total cardiovascular events in patients with cardiovascular disease: a prespecified analysis from the FOURIER trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(7):613–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2019.0886.

Deedwania PC, Pedersen TR, DeMicco DA, Breazna A, Betteridge DJ, Hitman GA, et al. Differing predictive relationships between baseline LDL-C, systolic blood pressure, and cardiovascular outcomes. Int J Cardiol. 2016;222:548–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.07.201.

Nassief A, Marsh JD. Statin therapy for stroke prevention. Stroke. 2008;39(3):1042–8. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.501361.

Pradhan A, Bhandari M, Vishwakarma P, Sethi R. Triglycerides and cardiovascular outcomes—can we REDUCE-IT? Int J Angiol. 2020;29(1):2–11. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1701639.

Heneghan C, Goldacre B, Mahtani KR. Why clinical trial outcomes fail to translate into benefits for patients. Trials. 2017;18(1):122. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-1870-2.

Stevanović J, Pechlivanoglou P, Kampinga MA, Krabbe PF, Postma MJ. Multivariate meta-analysis of preference-based quality of life values in coronary heart disease. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0152030. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152030.

Shiroiwa T, Sung YK, Fukuda T, Lang HC, Bae SC, Tsutani K. International survey on willingness-to-pay (WTP) for one additional QALY gained: what is the threshold of cost effectiveness? Health Econ. 2010;19(4):422–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1481.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

Ning Kam, Kanila Perera and Zanfina Ademi have no conflicts of interest to declare. Ella Zomer has received grants from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Pfizer and Shire, outside the submitted work. Danny Liew declares grant support from Abbvie, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CSL-Behring, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi and Shire, and past participation in advisory boards at Abbvie, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pfizer and Sanofi, outside the submitted work.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Code availability

Custom code is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

ZA conceived the idea and NK, KP, EZ and DL contributed to the design of the work. All authors contributed to the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work. NK drafted the manuscript. ZA, EZ and DL critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work ensuring integrity and accuracy.

Ethical standards

Ethics approval was not required as this study relied on published and publicly available data.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kam, N., Perera, K., Zomer, E. et al. Inclisiran as Adjunct Lipid-Lowering Therapy for Patients with Cardiovascular Disease: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. PharmacoEconomics 38, 1007–1020 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-020-00948-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-020-00948-w