Abstract

A substantial evidence base supports the use of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2is) in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). This class of medicines has demonstrated important benefits that extend beyond glucose-lowering efficacy to protective mechanisms capable of slowing or preventing the onset of long-term cardiovascular, renal and metabolic (CVRM) complications, making their use highly applicable for organ protection and the maintenance of long-term health outcomes. SGLT2is have shown cost-effectiveness in T2DM management and economic savings over other glucose-lowering therapies due to reduced incidence of cardiovascular and renal events. National and international guidelines advocate SGLT2i use early in the T2DM management pathway, based upon a plethora of supporting data from large-scale cardiovascular outcome trials, renal outcomes trials and real-world studies. While most people with T2DM would benefit from CVRM protection through SGLT2i use, prescribing hesitancy remains, potentially due to confusion concerning their place in the complex therapeutic paradigm, variation in licensed indications or safety perceptions/misunderstandings associated with historical data that have since been superseded by robust clinical evidence and long-term pharmacovigilance reporting. This latest narrative review developed by the Improving Diabetes Steering Committee (IDSC) outlines the place of SGLT2is within current evidence-informed guidelines, examines their potential as the standard of care for the majority of newly diagnosed people with T2DM and sets into context the perceived risks and proven advantages of SGLT2is in terms of sustained health outcomes. The authors discuss the cost-effectiveness case for SGLT2is and provide user-friendly tools to support healthcare professionals in the correct application of these medicines in T2DM management. The previously published IDSC SGLT2i Prescribing Tool for T2DM Management has undergone updates and reformatting and is now available as a Decision Tool in an interactive pdf format as well as an abbreviated printable A4 poster/wall chart.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Evidence shows that early and sustained optimisation of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) management is critical to prevent microvascular and macrovascular complications associated with progressive disease and, therefore, support long-term health outcomes. |

Current guidelines and expert opinion recommend the use of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2is) early in the T2DM treatment pathway based upon their clinical and economic value and proven beneficial effects in reducing and/or preventing diabetes-associated cardiovascular, renal and metabolic (CVRM) complications. |

Considering the wealth of data supporting these medicines, the Improving Diabetes Steering Committee (IDSC) expects SGLT2i therapies to take a more prominent role in future guidelines, potentially as a key component of standard care for newly diagnosed individuals with T2DM. |

The expansive evidence-base indicates that the proven advantages of SGLT2is in slowing or preventing the onset of serious CVRM complications and maintaining durable health outcomes should outweigh (or place into context) manageable issues (e.g. mycotic genital infections) and perceived potential risk of rare adverse events that may have previously delayed or deterred prescribing of these medicines for the right individuals. |

Practical tools have been developed by the IDSC to support healthcare professionals (HCPs) in gaining greater confidence regarding the appropriate use of SGLT2is and key resources are signposted for HCPs and people living with T2DM to assist in addressing common questions or issues relating to SGLT2i use in clinical practice. |

The Role of the Improving Diabetes Steering Committee

The Improving Diabetes Steering Committee (IDSC) is a multi-disciplinary group of healthcare professionals (HCPs) convened to offer evidence-informed practical guidance for the appropriate use of the sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor (SGLT2i) class of medicines in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). The Committee aims to produce materials that provide balanced review of the evidence and guidelines relating to use of SGLT2is in the management of T2DM, including their risk–benefit profile in reducing the risk of cardiovascular, renal and metabolic (CVRM) complications.

This narrative review summarises the key topics that were discussed during a Steering Committee meeting held in July 2023. The article is based upon previously conducted trials and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects. Some authors were involved in studies discussed within the paper that included human subjects, all of which complied with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and used protocols that had received Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee approval, with written informed consent provided by participants.

This paper aims to provide HCPs working in the field of T2DM with a practical understanding of the place, value and advantages of appropriate SGLT2i use in the T2DM treatment pathway. The main objectives for SGLT2i use are discussed alongside information on guideline-directed selection of suitable recipients and the cost–benefit case supporting these agents. As with the previous reviews published by the IDSC in Diabetes Therapy, the Committee has developed a range of pragmatic tools and materials to support HCPs [1,2,3,4]. These are provided within the body of the article as well as in the associated supplementary materials and include key practice points for HCPs prescribing SGLT2is, common frequently asked questions (FAQs) relating to SGLT2is (from the perspective of HCPs and people with T2DM) and a summary of helpful resources that are available for HCPs, people living with T2DM and those who care for them. Finally, the IDSC SGLT2i Prescribing Tool for T2DM Management has undergone an update and format change. It is now available as an SGLT2i Decision Tool, provided in an interactive pdf format, which can be downloaded as a supplementary material associated with this review paper.

Bridging the Gap Between Guidelines and Clinical Practice: Implementing Evidence-Informed, Person-Centred T2DM Management with SGLT2is

T2DM management has become increasingly complex over the past decade, with new medicines gaining regulatory approval and treatment pathways continually evolving to incorporate the latest data, new therapeutic indications and guideline recommendations. HCPs face ongoing challenges in healthcare settings dealing with multiple competing priorities and pressures. Unsurprisingly, such an environment fosters unintentional therapeutic inertia and does not support the prompt action that people living with T2DM need to gain control of their diabetes, lower their risk of cardiovascular (CV) and renal complications and maintain their health in the long term [5,6,7]. The latest guidelines published by the United Kingdom (UK) National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the American Diabetes Association (ADA)/European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) support the use of SGLT2i therapies early in the T2DM treatment paradigm for appropriate individuals and prescribing of SGLT2is has increased in response to the recommendations [7,8,9,10]. However, data indicate that use of these medicines remains suboptimal in clinical practice [7, 10]. There is a need for greater clarity and connection between current guidelines, expert consensus and the wealth of data surrounding SGLT2is in T2DM so that they are initiated at the right time to slow the onset and progression of CVRM complications and ensure the optimisation of overall health outcomes [5,6,7,8,9, 11, 12].

Data from the UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) have emphasised the importance of achieving and maintaining intensive T2DM management, from diagnosis, to prevent long-term microvascular complications [13, 14]. Elsewhere, data suggest that HbA1c may be better sustained with combination therapy, compared with stepwise T2DM treatment, and the debate regarding the advantages of intensive blood-glucose management in reducing adverse CV outcomes continues [15, 16]. The beneficial properties of oral glucose-lowering drugs in avoiding or decelerating progression toward macrovascular complications have been demonstrated in many studies and are well recognised in the literature and in current NICE, ADA/EASD, Primary Care Diabetes Europe and Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines, which advocate early combination therapy incorporating SGLT2is for appropriate individuals [3, 4, 8, 9, 11, 16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Diabetes therapy should aim to provide the maximum protection in the minimum time with the relative risks and side effects considered alongside other chronic diseases/comorbidities. Yet, traditional approaches to disease management encourage steady, phased intensification of treatment for chronic conditions, which can hinder the timely initiation of important therapeutic interventions that prevent the onset of life-altering complications [5, 6, 40]. T2DM medicines that protect the kidney and the heart provide additional clinical advantages beyond glycaemic outcomes. Furthermore, robust economic models have demonstrated the overwhelming value of appropriate SGLT2i prescribing [4, 41,42,43]. In higher-risk groups that include people with long-term diabetes and pre-existing complications, SGLT2is deliver cost savings across health services in as little as 2 years due to reduced CV and renal events, compared with other oral diabetes therapies [41]. Further studies are required to fully understand the economic impact of using SGLT2is during earlier stages of T2DM [44]. HCPs face many practical challenges when implementing guidelines in routine practice, including poor/fragmented attendance for regular T2DM reviews and lack of time and resources for adequate face-to-face consultations to allow opportunity for thorough clinical assessment. The guidelines place emphasis on individualised approaches to care, but better tools and resources are required to help simplify decision-making and address confusion/misconceptions relating to SGLT2i prescribing [8, 9, 32].

Back to Basics in T2DM Management: Improving Quantity and Quality of Life

HCPs working in primary care have the greatest impact on the health and well-being of individuals living with T2DM during the early years, after diagnosis [12, 45]. With progressive disease, the burden on primary care rises as CVRM complications and associated comorbidities require greater resource and time to manage, and patient quality of life (QoL) diminishes [12, 45,46,47]. Treatment must aim to improve and maintain enduring health while maximising the durability of any medicines prescribed [8, 9]. With swift and effective intervention following T2DM diagnosis, the course of disease can be altered to impede or prevent gradual progression toward chronic kidney disease (CKD)/diabetic kidney disease (DKD) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) [8, 9, 12, 37]. While the UKPDS trial was focused on intervention with metformin, sulphonylureas (SUs)/insulin or conventional diet approaches, the results from the 44-year follow-up revealed the important legacy effect of early intensive blood-glucose management in the reduction of microvascular complications and the improvement in clinical outcomes [13, 14]. Recently published registry data from Italy examining the associated risk of CVD in 251,339 people with T2DM and no CVD at baseline showed poor glycaemic outcomes (> 64 mmol/mol or HbA1c > 8%) during the first 3 years after diabetes diagnosis to be predictive of increased subsequent CVD risk, compared with having HbA1c < 53 mmol/mol (< 7%) [48]. Introduction of SGLT2i therapy during the initial 2 years appeared to remove the association between glycaemic management and CVD risk and early intervention seemed to be critical in achieving those outcomes [48]. The CVD-REAL study also demonstrated improvements in CV outcomes with SGLT2is, compared with other oral glucose-lowering treatments, in a real-world setting (in the United States, Norway, Denmark, Sweden, and the UK) [49, 50]. In the initial CVD-REAL analysis, the majority of participants (87%) did not have CVD at baseline and significant relative risk reductions regarding hospitalisation for heart failure (HHF; p < 0.001) and all-cause mortality (p < 0.001) were reported across the study population [49]. The CVD-REAL 3 study provided further real-world evidence concerning the impact of SGLT2is in decelerating kidney function decline (p < 0.0001) and the risk of major kidney events (p < 0.0001), compared with other oral glucose-lowering therapies [51]. Moreover, recent real-world data showed that increasing canagliflozin dosage to the highest approved level in individuals with T2DM and less-than-optimal metabolic results led to notable enhancements in key factors including fasting plasma glucose, HbA1c, body weight and blood pressure, complementing the existing cardiorenal protection offered by lower-dose therapy [52]. Real-world studies reaffirmed well-established data from large randomised controlled cardiovascular outcomes trials (CVOTs; EMPA-REG Outcome, CANVAS, DECLARE-TIMI 58), which have provided an ever-expanding body of evidence regarding SGLT2i-related reductions in CV events, including composite endpoints that encompass major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), heart failure (HF) and CV death, HHF and worsening HF events [17, 18, 53]. Renal outcomes trials, post hoc analysis from CVOTs and real-world studies have provided unequivocal evidence of the effectiveness of SGLT2is in reducing kidney disease and associated adverse outcomes [3, 21,22,23, 26, 28, 31, 36, 51, 54,55,56]. The CREDENCE trial focused on kidney outcomes in individuals with T2DM and albuminuric CKD [21]. It found that treatment with canagliflozin reduced the risk of the primary outcome, which comprised of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), doubling of serum creatinine, or death from renal or cardiovascular causes, by 30% in this high-risk population [21]. The EMPA-KIDNEY (empagliflozin) and DAPA-CKD (dapagliflozin) trials showed similar results in individuals with CKD, whether or not they had T2DM [21, 28, 31]. SGLT2i use has also been typically associated with the lowering of other CV risk factors, such as blood pressure, and recipients often experience weight loss [2, 12, 17, 18, 34, 35, 49, 52, 53, 57,58,59,60]. Organ protection remains the cornerstone objective for long-term management of T2DM and the wider implementation of SGLT2is early in the therapeutic pathway would support better outcomes through the lowering of both macrovascular risk and complication severity [1,2,3,4, 12, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23, 28, 31, 35, 52, 53, 56, 61].

Current Guidelines for SGLT2i Use in T2DM

While the NICE NG28 recommendations are used by the majority of UK HCPs to guide T2DM treatment decisions, there are some gaps in the current NICE guidelines that are considered in the ADA/EASD and KDIGO guidance [8, 9, 32]. The NG28 guideline recommends initiation of SGLT2i therapy in combination with metformin (once metformin tolerability has been confirmed) for individuals with high CV risk, established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), comorbid HF and comorbid CKD [8]. SGLT2i monotherapy is also advocated for use in high-risk individuals with T2DM who are unable to tolerate metformin [8]. NICE recommends the use of the QRISK2® tool (QRISK®3 is also available as an updated version to use online but is currently less widely integrated in primary care systems) to assess a person’s risk of CVD [8]. People with T2DM who are under the age of 40 years and therefore unsuitable for QRISK assessment should be considered at high risk if they have one or more CV risk factor, defined as hypertension, dyslipidaemia, smoking, obesity, and family history (in a first-degree relative) of premature CVD [8]. According to ADA/EASD guidelines, SGLT2is may be used as a first-line treatment in combination with other glucose-lowering therapies (or alone) where the treatment goal is to achieve and maintain glycaemic and weight management targets, with early combination therapy endorsed to optimise outcomes and extend the time to therapeutic failure [9]. Under the same guidelines, SGLT2is are the recommended first-line therapy (in addition to comprehensive CV risk-management strategies) when the goal of treatment is cardiorenal risk reduction in high-risk people with T2DM, comprising those with known cardiorenal disease (established CVD/HF/CKD) or indicators of high ASCVD risk [9]. The Primary Care Diabetes Europe position statement recommends combining SGLT2i therapy with metformin for individuals with T2DM and HF or CKD, ensuring both glycaemic control and cardiorenal protection [33]. The KDIGO 2022 recommendations include SGLT2is within their comprehensive care strategy to reduce the risk of kidney disease progression and CVD in people with diabetes [32]. KDIGO supports combination therapy with metformin and an SGLT2i and advises that SGLT2is may be initiated when estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is ≥ 20 ml/min/1.73 m2 and continued (as tolerated), until dialysis or transplantation is initiated [32]. Likewise, the UK Kidney Association (UKKA) recommends SGLT2is for people with T2DM and eGFR ≥ 25 ml/min/1.73 m2 attributed to diabetic nephropathy and in people with T2DM and coronary disease or stable symptomatic HF (irrespective of ejection fraction) [62,63,64,65,66].

An update to the NG28 recommendations is due to be published toward the end of 2024, but it remains unclear whether NICE will take a similar approach to that of the ADA/EASD or KDIGO in supporting the upfront use of SGLT2is following diagnosis and CVRM risk assessment [8]. The European Society for Cardiology (ESC) currently supports the use of SGLT2i in people with HF and T2DM at risk of CV events to reduce HHF, major CV events, end-stage renal dysfunction and CV death and these guidelines are also due to be updated in 2024 [67, 68]. Current guidelines do not specifically mention fixed-dose SGLT2i-metformin combinations, but there may be scope for such treatments in people with T2DM, once they are stable on individual treatments.

Future direction for guidelines should account for the additional value offered by SGLT2is in relation to weight management, blood pressure lowering, CVRM risk reduction and economic benefit. The IDSC would expect more prominent positioning of SGLT2i therapy among first-line treatment options for a wider range of people with T2DM in upcoming guidelines, due to their protective properties. Key caveats regarding the prescribing of SGLT2i agents in a wider population would include people living with frailty and women of childbearing age. Any recommendations regarding SGLT2i use in older people should include frailty assessments and the potential for postural hypotension, which may be more common in this group due to factors including comorbidities, concomitant medications and changes in water/sodium balance with SGLT2is [63,64,65,66, 69]. Rising prevalence of T2DM in younger people has major implications regarding long-term management of disease and risk. Evidence from the TODAY study suggests that younger people with T2DM have high lifetime CVD risk and rapidly progressing complications tend to appear early in this group making the need for prompt intensive treatment all the more important [8, 70, 71]. SGLT2is are not licensed for use during pregnancy and data are lacking regarding potential fertility implications [63,64,65,66]. Although women under 40 years of age with T2DM can benefit from SGLT2is, it is important to prescribe these medications only when they are using reliable contraception. The QRISK®3-Lifetime tool may be more appropriate for assessment of people aged 18–40 years since QRISK®2 estimates a 10-year risk and may underestimate lifetime CV risk, resulting in eligible people with young onset T2DM being overlooked for SGLT2i treatment [8, 72, 73]. People aged < 40 years with at least one CV risk factor are considered appropriate to begin SGLT2i treatment, which should not then be stopped when they reach 40 years of age (even if their QRISK score is < 10%) as individuals will continue to gain protection against CV, renal and metabolic complications of T2DM [8, 71].

The Cost–Benefit Case for SGLT2is

Understanding value in healthcare is important in the context of rapidly expanding populations, widespread ill health and greater use of health technologies. However, increasingly, prospective cost analyses do not represent the true value and economic impact of treatments/technologies from a holistic, multisystem, multistakeholder perspective. Stakeholders in the healthcare setting include not only people living with diabetes, but also payers, healthcare systems, carers, social care and the wider society. While evaluating healthcare value through cost-effectiveness analyses, it is crucial to recognise that medical interventions yield social returns on investments beyond utility. Integrated Care Boards in England often review prescriptions as spending exceeds a threshold, prompting healthcare providers to assess whether drug treatments align with clinical and economic rationale. This is particularly relevant for SGLT2is, which may (by conservative estimates) be appropriate for the treatment of approximately 1.7 million people with T2DM in England alone, if prescribed according to the current NICE NG28 guideline [74].

SGLT2is can offer value across the natural history and continuum of T2DM. Early in the treatment pathway, value is offered through health gain associated with better metabolic outcomes, weight loss, reduced blood pressure and low risk of hypoglycaemia [1, 35, 37, 57,58,59,60]. Progressing through the course of T2DM, SGLT2is are associated with reduced CVD, renal disease and HF, delivering health gain as well as cost savings via reduced resource utilisation and effective management of complications and releasing capacity within the system [3, 4, 17,18,19,20,21,22, 28, 29, 31, 41, 44, 53, 55, 56, 75,76,77]. Systematic review data examining the results of 24 studies revealed SGLT2i therapy to be cost-effective in T2DM management when compared against treatment with dipeptidyl-peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4is), SUs, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) and other glucose-lowering therapies that included thiazolidinediones, alpha-glucosidase inhibitors and insulin [43]. A recent study by McEwan et al. (2023) demonstrated cost-effectiveness and cost-savings with SGLT2is alongside improvements in health outcomes (e.g. HHF, CKD) when implemented in eligible populations (high CV risk, established ASCVD, comorbid HF and comorbid CKD), according to NICE NG28 guidelines [41]. Analyses examined relative spending, treatment effects (changes in HbA1c, weight, and rates of hypoglycaemia) and cardiorenal complications in terms of predicted lifetime costs, quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and total life-years, comparing outcomes for SGLT2is with those of SU treatment and DPP-4is [41]. An overall cost-saving was associated with SGLT2i use, versus SU or DPP-4i treatment, for each of the populations specified as appropriate for SGLT2i therapy in the NG28 guidelines [41]. All spending increases associated with additional prescribing were substantially offset by the lowering of management costs for expected complications of T2DM [41]. The time to cost saving status is a critical consideration when establishing the value of a medicine or healthcare technology. Compared with SUs or DPP-4is, the analysis by McEwan et al. [41] showed SGLT2is to be cost-effective from initiation (over a 25-year projection) and costs savings were predicted against DPP-4is within 2 years for comorbid HF and CKD populations, and within 9–11 years for ASCVD and high CVD risk groups [41]. In comparison with SUs, the time to cost savings with SGLT2i treatment ranged between 5 years for the comorbid CKD population and 16 years for people with high CVD risk [41]. Published studies examining the cost-effectiveness of first-line SGLT2i use in people living with T2DM are limited and do not evaluate the value of SGLT2is within the whole healthcare system, beyond simple cost-effectiveness analyses, in view of their multiple indications and reported outcomes (e.g. delaying the onset and progression of DKD) [21, 28, 31, 44, 55, 78]. However, in the UK, NICE approved SGLT2is as first-line treatment in cases where metformin is not indicated or tolerated (when SU or pioglitazone is not appropriate) in 2016, before many of the CVOT and renal outcomes trials were published [79]. This recommendation was based on a detailed network meta-analysis and systematic review of cost-effectiveness data [79].

When implemented appropriately, SGLT2is could offer cost savings in those high-risk populations defined by the NICE NG28 recommendations and they should be highly cost-effective in the rest of the T2DM population [41, 43, 74]. A clear whole system value gain would be seen with outcomes set in the context of reduced expenditure and resource usage due to slower progression of disease, fewer complications and CVD or ESKD events. Reduced bed day occupancy for CVD and ESKD events would release greater capacity within the healthcare system and result in less waste and enhanced efficiency. Maintaining health and well-being for longer would enable people living with T2DM to continue working and actively contributing to society. The greatest value should be obtained from initiating SGLT2i treatment before complications have begun as incident HF, ESKD events and other events should be reduced. Based on the clinical and health economic gains associated with SGLT2is, the IDSC would support earlier and increased use of these medicines in appropriate individuals with T2DM.

A Step-Change in T2DM Management: Bridging the Gap Between Guidelines and Routine Clinical Practice

The NICE resource impact report for T2DM in adults suggested that around 1.7 million people with T2DM in England (approximately 50% of the T2DM population) should be eligible for SGLT2i treatment and the cost savings relating to their implementation have been recognized by NICE [74]. However, current data indicate that prescribing practices are in the region of 27% for this population [10]. This raises the question as to why there might be such disparity between current guidelines and clinical practice. Given the existing weight of evidence and growing expert opinion/support in this area, the IDSC estimates that the proportion of people with T2DM who would benefit from SGLT2i treatment could be closer to 80%. Guideline fatigue, confusion and misconceptions regarding safety risks have represented a barrier to SGLT2i uptake in primary care since these agents first became available [7, 12, 80]. These aspects must be addressed to help colleagues understand how optimised use of SGLT2is may assist in releasing capacity and avoiding the occurrence of future complications that will only increase pressure on already over-stretched systems.

The wide-ranging advantages associated with SGLT2is in maintaining overall health and enduring CVRM outcomes far outweigh the observed incidence of potential adverse events (AEs). Figure 1 is adapted from the results reported by a meta-analysis of randomised data on kidney outcomes conducted by the Nuffield Department of Population Health Renal Studies Group (2022) [36]. The figure shows that, in people with T2DM and ASCVD, stable HF or CKD, the incidence of CVRM events (per 1000 patient-years) was substantially reduced with SGLT2i use while the incidence of AEs (e.g. ketoacidosis) was slightly raised in these high-risk T2DM subgroups [36]. The overwhelming weight of evidence indicates that SGLT2i treatment provides an overall advantage in improving long-term T2DM outcomes and avoiding CVRM events when compared against the risk of drug-related AEs (Fig. 2) [2,3,4, 8, 9, 11, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31, 41, 49, 51, 56, 81, 82].

Adapted from Nuffield Department of Population Health Renal Studies Group, SGLT2 inhibitor Meta-Analysis Cardio-Renal Trialists’ Consortium. Impact of diabetes on the effects of sodium glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors on kidney outcomes: collaborative meta-analysis of large placebo-controlled trials. Lancet. 2022;400:1788–801 [36]. The figure shows the specific absolute effects on adverse events associated with SGLT2i use in people with T2DM, based on large-scale randomised trials. The absolute effects were estimated by applying the specific relative risk of an event in the active treatment arm to the average event rate in the placebo arms (first event only). Negative numbers indicate events avoided by SGLT2 inhibition per 1000 patient-years. Mean eGFR values are given for combined trial populations. ASCVD atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, CKD chronic kidney disease, CV cardiovascular, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, LLA lower limb amputation, SGLT2i sodium glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor, T2DM type 2 diabetes mellitus

Change in risk of adverse events with SGLT2is for people with T2DM [36].

Schematic representation of the relative risk and benefit profile for SGLT2i therapies based upon RCT and real-world data [2,3,4, 8, 9, 11, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31, 41, 49, 51, 56, 81, 82]. CKD chronic kidney disease, CV cardiovascular, CVD cardiovascular disease, DKA diabetic ketoacidosis, DKD diabetic kidney disease, ESKD end-stage kidney disease, LLAs lower limb amputations, RCT randomised controlled trial

Variation and changes in individual licence indications in people with reduced eGFR have fuelled misunderstandings about the appropriate circumstances for initiation and continuation of these agents when kidney function is impaired [63,64,65,66]. Each of the currently available SGLT2i agents are licensed for initiation in people with eGFR < 45 ml/min/1.73 m2, with product-specific caveats concerning initiation and continuation of treatment at eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2 and dosing (although dapagliflozin may be used in people with eGFR 15 ml/min/1.73 m2) [63,64,65,66, 83]. SGLT2i mechanism of action results in significantly reduced glucose-lowering effect when eGFR is < 45 ml/min/1.73 m2 and additional T2DM therapy will be needed if HbA1c is above target, although individuals will still benefit from the CVRM protection and slowing of further decline in kidney function offered by SGLT2is [8, 9, 32, 62, 83].

Fear of increased diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) risk represents a significant barrier to SGLT2i use. Risk factors for this rare but serious condition include pronounced insulin resistance, low beta-cell function including those with T2DM and low C-peptide levels (particularly in people with latent autoimmune diabetes in adults [LADA]/slowly evolving immune-related diabetes or a history of pancreatitis), restricted food intake (very low calorie or carbohydrate diets) or severe dehydration, sudden reduction in insulin or increased insulin requirements due to rising counter-regulatory hormones (e.g. during acute illness), major surgery and alcohol abuse [84, 85]. Two recently reported cases of severe ketoacidosis triggered by reduced oral nutrition intake in people taking SGLT2i therapy for HF show that ketoacidosis can occur in people without T2DM and risk factors, such as dietary intake, should be considered for all indications [86]. As highlighted in the ADA/EASD guidelines, incidence of DKA is low in general and SGLT2is are associated with a small incremental increase in absolute risk [9]. Published CVOTs reported DKA rates ranging between 0.1 and 0.6% in the SGLT2i treatment arm and < 0.1 and 0.3% in the placebo arm across studies [9, 17, 18, 29, 53]. Ketoacidosis was not observed in non-diabetes subgroups participating in the DAPA-CKD trial and one case was reported in an individual without T2DM at baseline in the empagliflozin EMPA-KIDNEY study, indicating that such events are generally associated with the presence of T2DM itself [28, 31]. Clear written and verbal education regarding sick day guidance and the signs of DKA can help to manage and place the risk of this rare adverse event into context [84, 87]. The main signs include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, shortness of breath (Kussmaul breathing), drowsiness, confusion and sweet-smelling (pear drop) breath [84]. DKA can occur with euglycaemia (relatively normal glucose levels) during SGLT2i use and HCPs should be aware of this and check ketone levels in individuals who are unwell, even in the setting of relatively normal blood glucose levels [84]. Individuals should be advised to seek medical guidance if they are feeling unwell, even if their blood glucose does not appear elevated [84]. SGLT2i treatment will need to be temporarily paused if symptoms develop, with the decision to restart (where a clear contributing factor has been identified) taken in discussion with the individual and clinical team when it has been established that the benefits of reintroducing an SGLT2i outweigh the risks [84, 87]. Where a person has paused SGLT2i treatment in line with specialist care instructions (e.g. fasting in preparation for surgery), instructions for restarting SGLT2i therapy should be clearly given. Current recommendations vary widely according to country and suggest that SGLT2is must be stopped 3–7 days prior to planned surgery or a procedure requiring nil by mouth [88, 89]. However, the IDSC would advise ceasing SGLT2i therapy the day before surgery and then restarting once normal oral intake has been established and the person’s condition has stabilised.

Genital mycotic infections (vulvovaginitis and balanitis) can occur during SGLT2i treatment, with infections being more common in women than men and usually arising early in treatment [63,64,65,66, 87]. Severe bacterial urinary tract infections (such as pyelonephritis and urosepsis) are rare, and analysis of trial data and real-world evidence does not support a causal link with SGLT2i treatment [90, 91]. Standard topical or oral antifungal or antibiotic treatments are generally sufficient to manage minor genital infections and most people can continue taking their SGLT2i medication [87]. Glucosuria may cause urinary symptoms, including more frequent voiding, and people with diabetes should receive education regarding the importance of post-micturition genital hygiene and hydration [63,64,65,66, 87].

Over the past decade, clinical experience, data from randomised controlled trials (RCTs), and real-world evidence have helped to enhance understanding of the risks associated with SGLT2is, particularly the rare but severe AEs such as Fournier's gangrene (FG), a perineal tissue infection, and lower limb amputations (LLAs) [92,93,94,95]. Yet, there is still uncertainty surrounding these potential side effects. Continued placement of historical warnings regarding FG and LLAs on the UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA)/Department of Health (DoH) website as well as those in the British National Formulary (BNF) add further uncertainty for HCPs concerning actual risk levels for people who might otherwise be suitable for treatment [81, 82]. The MHRA, DoH and BNF statements are based upon outdated data, which have since been superseded by reassuring clinical outcomes from large scale CVOT and kidney disease trials conducted in high-risk populations [17, 18, 21, 53]. These studies showed that the incidence of FG was low and not confined to the active treatment arm, with higher incidence in the placebo arm in some trials (DAPA-CKD; DECLARE) [17, 18, 21, 28, 53]. Recent combined post hoc analysis from RCTs conducted in people with T2DM and high CV risk and/or CKD, the CANVAS Program and CREDENCE, showed that canagliflozin treatment did not affect the risk of non-genital skin and soft tissue infections compared with placebo [92]. People living with diabetes are inherently at elevated risk for LLA events [87, 96, 97]. Excess amputations were reported in one CVOT and were not replicated across subsequent trials [17, 18, 21, 28, 53, 98, 99]. Everyone with T2DM should be educated regarding the importance of preventative foot care and regular comprehensive assessment of lower limbs must be included in clinical reviews [8, 87, 96, 100]. Risk factors for LLAs include prior amputation, peripheral vascular disease and peripheral neuropathy, although these groups may gain advantage through the lowering of CVD risk associated with SGLT2is [87, 96, 100]. The Nuffield Department of Population Health Renal Studies Group meta-analysis stressed that the disease-modifying effects and absolute benefits of SGLT2i treatment outweighed any serious hazards of ketoacidosis or limb amputation [36]. Awareness of the key signs and symptoms is critical so that prompt and appropriate action can be taken when required for all people with T2DM. In addition, the osmotic diuretic effects of SGLT2i therapies may be advantageous for people who have limb-dependent oedema, even with active ulceration. Discussion with the local diabetes foot multidisciplinary team (MDT) is warranted if SGLT2is are considered suitable in this situation. Experts across the field are currently working to develop a Delphi consensus statement regarding the diabetic foot, which will help in guiding appropriate use of medicines in high-risk individuals. It is hoped that the consensus will be available during the early part of 2024.

The risk factors discussed above are of particular relevance when considering the use of any glucose-lowering medicines in older people or those living with frailty [101]. Assessment of frailty level should be conducted regularly, as it is a dynamic parameter that changes over time, according to an individual’s current circumstances [101]. Routine assessment of risk concerning urinary continence (due to potential urine infection), falls and perineal cutaneous infection must be conducted for older people with T2DM who are currently prescribed an SGLT2i. The decision to use an SGLT2i should consider the possibility of volume depletion and postural hypotension, which may increase the likelihood of falls, particularly in people who are also treated with diuretics or antihypertensives [17, 18, 53, 63,64,65,66, 101]. Older participants (aged > 65 years) included in the CVOT studies typically demonstrated higher rates of volume depletion, compared with younger subgroups, although the overall rates were similar across the treatment and placebo arms in the DECLARE-TIMI (dapagliflozin) and EMPA-REG (empagliflozin) trials [18, 53, 102]. On the other hand, the CREDENCE and DAPA-CKD studies did not encounter any issues relating to concomitant use of SGLT2is and loop diuretics and some participants in the T2DM subgroups for HF trials (DAPA-HF and EMPEROR-reduced) were taking high-dose diuretics, and no dose reduction was necessary [20, 21, 28, 75, 103,104,105].

SGLT2i agents appear to offer electrolyte sparing advantages, although the pathophysiological mechanisms remain poorly understood [104, 106,107,108,109,110]. In general, potassium, magnesium and sodium, levels seem to be unaffected by SGLT2i treatment [104, 106,107,108,109,110]. Meta-analysis from CVOT and renal outcomes trials including 50,000 people with T2DM and high CV risk or CKD reported a 16% reduction of incident hyperkalaemia with SGLT2i treatment compared with placebo (p < 0.001) and no increase in hypokalaemia [108]. These properties may provide greater flexibility regarding dose optimisation for renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitor (RAASi) drugs and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs), which can be limited by hyperkalaemia, particularly with kidney function decline [108]. SGLT2i renal outcomes and HF trials have shown that the CVRM benefits associated with SGLT2i use occur independently of MRA use in high-risk patients, many of whom will be receiving polypharmacy (with RAASi and/or MRA agents) in clinical practice [20, 76, 111, 112]. Systematic review and network meta-analysis data have identified that SGLT2is or nonsteroidal MRAs, combined with RAASi drugs, resulted in a reduction in kidney-specific composite events and HHF in people with T2DM and CKD, compared with placebo [112]. The NICE NG28 guideline does not provide advice on whether a person should be taking SGLT2i therapy before or after initiating MRA therapy and this lack of clarity also extends to the use of other glucose-lowering medicines in the treatment pathway (e.g. GLP-1 RAs) [8, 113]. However, the NICE technology appraisal guidance for finerenone states that people with T2DM and CKD can be prescribed finerenone in addition to angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs), if they are not working well enough, and could be offered before, after, or with an SGLT2i [114]. KDIGO recommendations also state that nonsteroidal MRA agents can be added to first-line therapy (including SGLT2is) for people with T2DM and high residual risk of kidney disease progression and CV events, as evidenced by persistent albuminuria [32].

Post hoc analyses of CVOT data and real-world studies have revealed that the use of SGLT2i therapy is associated with lower serum urate levels and reduced incidence of gout [115,116,117,118,119]. In addition, a recent cohort study indicated that people T2DM and gout were at lower risk of recurrent gout flares and mortality if they were treated with an SGLT2i, compared with other oral glucose-lowering therapies [120].

Practical Tools to Support Better Management of T2DM

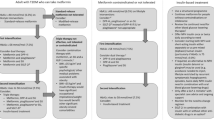

Figure 3 provides a traffic light summary of the clinical situations in which the IDSC believes that SGLT2i therapy should be offered to people with T2DM (green), SGLT2is should be considered (amber) or SGLT2i treatment should not be prescribed (red). To provide support in navigating each of these clinical situations and the topics discussed throughout this review in clinical practice, further information and practical advice are provided in the revised IDSC SGLT2i Decision Tool, which can be downloaded in an interactive pdf format as a supplementary material associated with this article alongside a printable one-page A4 poster/wall chart summary.

SGLT2i decision tool—abbreviated summary [8, 9, 12, 17, 18, 21, 28, 31, 32, 41, 43, 51, 53,54,55, 62,63,64,65,66, 71, 74, 82,83,84, 87, 101, 110, 121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129]. The full SGLT2i Decision Tool can be viewed and downloaded in an interactive pdf format from the supplementary materials associated with this narrative review paper. ASCVD atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, BMI body mass index, CKD chronic kidney disease, CVD cardiovascular disease, DKD diabetic kidney disease, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, GLP-1 RA glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, HbA1c glycated haemoglobin A1c, LADA latent autoimmune diabetes in adult, PAD peripheral arterial disease, PEI pancreatic exocrine insufficiency, QRISK cardiovascular risk score, SGLT2i sodium glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor, SmPC summary of product characteristics, T2DM type 2 diabetes mellitus, UACR urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio, UTIs urinary tract infections

Putting the evidence in to practice, the IDSC supports the implementation of a rapid sequential approach to T2DM management comprising early combination therapy with metformin and an SGLT2i agent for most people with T2DM, rather than gradual stepwise intensification of treatment over an extended period. Using this method, metformin should be initiated and titrated to an appropriate dose during the first month, with the SGLT2i agent added (unless contraindicated) after 4 weeks (supported by a telephone appointment, where possible) or by a review after 12 weeks (at latest). For high-risk individuals (high CV risk, CVD or kidney disease), an SGLT2i should be started at diagnosis, with or without other diabetes therapies, in line with ADA/EASD and KDIGO guidelines [9, 32].

It is important to discuss the relative risks and benefits with the person being prescribed an SGLT2i to ensure that they broadly understand how these treatments work and have an opportunity to ask questions. To minimise the chances of experiencing an AE that will discourage an individual from persisting with newly initiated SGLT2i medication, advice should be given regarding the importance of maintaining good daily hydration and genital hygiene. Information about genital infections and the signs and symptoms of DKA should be communicated with an emphasis on the fact that ketoacidosis and FG are very rare events in usual practice. Counselling the individual about the importance of avoiding very low carbohydrate or ketogenic diets and ensuring continued hydration while taking an SGLT2i will help to reduce the risk of rare but serious events [84, 87]. Sick day guidance should be given, with clear instructions on pausing SGLT2i therapy while the person is unwell and they must be encouraged to contact their HCP if they need assistance in restarting treatment once they have recovered [121]. Box 1 provides a summary of key practice points to guide a T2DM consultation in which an SGLT2i agent is initiated. The answers to common FAQs are also provided in Box 2 to support HCPs in answering their own questions about SGLT2is. Box 3 provides responses to queries that a person with T2DM may have when they are prescribed an SGLT2i. Finally, Box 4 contains links to key resources for HCPs and people with T2DM relating to SGLT2i treatment. Variation in approved SGLT2i product licences continues to be a cause for confusion among prescribers, particularly relating to eGFR, and the IDSC advocates the use of recently published summaries, such as those provided in ‘Prescribing SGLT2i therapy’ section in Box 4, which give a useful and practical overview. Other areas covered by the links in Box 4 include current guidelines and information relating to DKA, genital infections and sick day guidance. Links to many of these materials are also provided via the SGLT2i Decision Tool (supplementary materials).

References

Wilding J, Fernando K, Milne N, Evans M, Ali A, Bain S, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes management: key evidence and implications for clinical practice. Diabetes Ther. 2018;9:1757–73.

Ali A, Bain S, Hicks D, Newland Jones P, Patel DC, Evans M, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors: cardiovascular benefits beyond HbA1c-translating evidence into practice. Diabetes Ther. 2019;10:1595–622.

Wheeler DC, James J, Patel D, Viljoen A, Ali A, Evans M, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors: slowing of chronic kidney disease progression in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2020;11:2757–74.

Wilding JPH, Evans M, Fernando K, Gorriz JL, Cebrian A, Diggle J, et al. The place and value of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors in the evolving treatment paradigm for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a narrative review. Diabetes Ther. 2022;13:847–72.

Reach G, Pechtner V, Gentilella R, Corcos A, Ceriello A. Clinical inertia and its impact on treatment intensification in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. 2017;43:501–11.

Almigbal TH, Alzarah SA, Aljanoubi FA, Alhafez NA, Aldawsari MR, Alghadeer ZY, et al. Clinical inertia in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59:182.

Schernthaner G, Shehadeh N, Ametov AS, Bazarova AV, Ebrahimi F, Fasching P, et al. Worldwide inertia to the use of cardiorenal protective glucose-lowering drugs (SGLT2i and GLP-1 RA) in high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19:185.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Type 2 diabetes in adults: management. NICE guideline. NG28. 2022.

Davies MJ, Aroda VR, Collins BS, Gabbay RA, Green J, Maruthur NM, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2022, a consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia. 2022;65:1925–66.

IQVIA. Longitudinal prescription data: SGLT2 inhibitor prescribing data for England. 2023.

Thomas MC, Neuen BL, Twigg SM, Cooper ME, Badve SV. SGLT2 inhibitors for patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD: a narrative review. Endocr Connect. 2023;12: e230005.

Evans M, Morgan AR, Bain SC, Davies S, Dashora U, Sinha S, et al. Defining the role of SGLT2 inhibitors in primary care: time to think differently. Diabetes Ther. 2022;13:889–911.

Alder A. United Kingdom Prospective Study (UKPDS) 44-year follow-up symposium. UKPDS perspective, legacy effects and 44-year follow-up data [Internet]. Hybrid 58th EASD Annual Meeting. 2022 [cited 2023 Dec 19]. https://www.easd.org/media-centre/#!resources/ukpds-perspective-legacy-effects-and-44-year-follow-up-data. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

Holman RR. United Kingdom Prospective Study (UKPDS) 44-year follow-up symposium. Clinical outcomes at 44 years: do the legacy effects persist? [Internet]. Hybrid 58th EASD Annual Meeting. 2022 [cited 2023 Dec 19]. https://www.easd.org/media-centre/#!resources/clinical-outcomes-at-44-years-do-the-legacy-effects-persist. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

Matthews D, Del Prato S, Mohan V, Mathieu C, Vencio S, Chan JCN, et al. Insights from VERIFY: early combination therapy provides better glycaemic durability than a stepwise approach in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2020;11:2465–76.

Giugliano D, Maiorino MI, Bellastella G, Chiodini P, Esposito K. Glycemic control, preexisting cardiovascular disease, and risk of major cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review with meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials and intensive glucose control trials. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8: e012356.

Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, de Zeeuw D, Fulcher G, Erondu N, et al. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:644–57.

Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, Mosenzon O, Kato ET, Cahn A, et al. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:347–57.

Packer M, Butler J, Zannad F, Filippatos G, Ferreira JP, Pocock SJ, et al. Effect of empagliflozin on worsening heart failure events in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: EMPEROR-preserved trial. Circulation. 2021;144:1284–94.

Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Ferreira JP, Pocock SJ, et al. Effect of empagliflozin on the clinical stability of patients with heart failure and a reduced ejection fraction. Circulation. 2021;143:326–36.

Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, Bompoint S, Heerspink HJL, Charytan DM, et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2295–306.

Heerspink HJL, Desai M, Jardine M, Balis D, Meininger G, Perkovic V. Canagliflozin slows progression of renal function decline independently of glycemic effects. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:368–75.

Barraclough JY, Yu J, Figtree GA, Perkovic V, Heerspink HJL, Neuen BL, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with canagliflozin in patients with peripheral arterial disease: data from the CANVAS Program and CREDENCE trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2022;24:1072–83.

Gonzalez Perez A, Vizcaya D, Sáez ME, Lind M, Garcia Rodriguez LA. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes among patients with type 2 diabetes using SGLT2 inhibitors added to metformin: a population-based cohort study from the UK. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2023;11: e003072.

Salvatore T, Galiero R, Caturano A, Rinaldi L, Di Martino A, Albanese G, et al. An overview of the cardiorenal protective mechanisms of SGLT2 inhibitors. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:3651.

Forbes AK, Suckling RJ, Hinton W, Feher MD, Banerjee D, Cole NI, et al. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors and kidney outcomes in real-world type 2 diabetes populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2023;25:2310–30.

Lo KB, Gul F, Ram P, Kluger AY, Tecson KM, McCullough PA, et al. The effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on cardiovascular and renal outcomes in diabetic patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiorenal Med. 2020;10:1–10.

Heerspink HJL, Stefánsson BV, Correa-Rotter R, Chertow GM, Greene T, Hou F-F, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1436–46.

Cannon CP, Pratley R, Dagogo-Jack S, Mancuso J, Huyck S, Masiukiewicz U, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes with ertugliflozin in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1425–35.

Zelniker TA, Wiviott SD, Raz I, Im K, Goodrich EL, Bonaca MP, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. Lancet. 2019;393:31–9.

The EMPA-KIDNEY Collaborative Group. Empagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:117–27.

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Diabetes Work Group. KDIGO. clinical practice guideline for diabetes management in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2022;2022(102):S1-127.

Seidu S, Cos X, Brunton S, Harris SB, Jansson SPO, Mata-Cases M, et al. 2022 update to the position statement by Primary Care Diabetes Europe: a disease state approach to the pharmacological management of type 2 diabetes in primary care. Prim Care Diabetes. 2022;16:223–44.

Shyangdan DS, Uthman OA, Waugh N. SGLT-2 receptor inhibitors for treating patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6: e009417.

Zaccardi F, Webb DR, Htike ZZ, Youssef D, Khunti K, Davies MJ. Efficacy and safety of sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18:783–94.

Nuffield Department of Population Health Renal Studies Group, SGLT2 inhibitor Meta-Analysis Cardio-Renal Trialists’ Consortium. Impact of diabetes on the effects of sodium glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors on kidney outcomes: collaborative meta-analysis of large placebo-controlled trials. Lancet. 2022;400:1788–801.

Marassi M, Fadini GP. The cardio-renal-metabolic connection: a review of the evidence. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22:195.

Scheen AJ. The current role of SGLT2 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes and beyond: a narrative review. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2023;18:271–82.

Chipayo-Gonzales D, Shabbir A, Vergara-Uzcategui C, Nombela-Franco L, Jimenez-Quevedo P, Gonzalo N, et al. Treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with diabetes mellitus and extensive coronary artery disease: mortality and cardiovascular outcomes. Diabetes Ther. 2023;14:1853–65.

Strain WD, Cos X, Hirst M, Vencio S, Mohan V, Vokó Z, et al. Time to do more: addressing clinical inertia in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;105:302–12.

McEwan P, Foos V, Martin B, Chen J, Evans M. Estimating the value of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors within the context of contemporary guidelines and the totality of evidence. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2023;25:1830–8.

Morton JI, Marquina C, Shaw JE, Liew D, Polkinghorne KR, Ademi Z, et al. Projecting the incidence and costs of major cardiovascular and kidney complications of type 2 diabetes with widespread SGLT2i and GLP-1 RA use: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Diabetologia. 2023;66:642–56.

Yoshida Y, Cheng X, Shao H, Fonseca VA, Shi L. A systematic review of cost-effectiveness of sodium-glucose cotransporter inhibitors for type 2 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2020;20:12.

Chin KL, Ofori-Asenso R, Si S, Hird TR, Magliano DJ, Zoungas S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of first-line versus delayed use of combination dapagliflozin and metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes. Sci Rep. 2019;9:3256.

Hodgson S, Morgan-Harrisskitt J, Hounkpatin H, Stuart B, Dambha-Miller H. Primary care service utilisation and outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a longitudinal cohort analysis. BMJ Open. 2022;12: e054654.

Nowakowska M, Zghebi SS, Ashcroft DM, Buchan I, Chew-Graham C, Holt T, et al. The comorbidity burden of type 2 diabetes mellitus: patterns, clusters and predictions from a large English primary care cohort. BMC Med. 2019;17:145.

Zghebi SS, Steinke DT, Rutter MK, Ashcroft DM. Eleven-year multimorbidity burden among 637 255 people with and without type 2 diabetes: a population-based study using primary care and linked hospitalisation data. BMJ Open. 2020;10: e033866.

Ceriello A, Lucisano G, Prattichizzo F, La Grotta R, Frigé C, De Cosmo S, et al. The legacy effect of hyperglycemia and early use of SGLT-2 inhibitors: a cohort study with newly-diagnosed people with type 2 diabetes. Lancet Region Health Eur. 2023;31: 100666.

Kosiborod M, Cavender MA, Fu AZ, Wilding JP, Khunti K, Holl RW, et al. Lower risk of heart failure and death in patients initiated on sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors versus other glucose-lowering drugs: the CVD-REAL study (comparative effectiveness of cardiovascular outcomes in new users of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors). Circulation. 2017;136:249–59.

Khunti K, Kosiborod M, Kim DJ, Kohsaka S, Lam CSP, Goh S-Y, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes with sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors vs other glucose-lowering drugs in 13 countries across three continents: analysis of CVD-REAL data. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2021;20:159.

Heerspink HJL, Karasik A, Thuresson M, Melzer-Cohen C, Chodick G, Khunti K, et al. Kidney outcomes associated with use of SGLT2 inhibitors in real-world clinical practice (CVD-REAL 3): a multinational observational cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:27–35.

Gorgojo-Martinez JJ, Ferreira-Ocampo PJ, Galdón Sanz-Pastor A, Cárdenas-Salas J, Antón-Bravo T, Brito-Sanfiel M, et al. Effectiveness and tolerability of the intensification of canagliflozin dose from 100 mg to 300 mg daily in patients with type 2 diabetes in real life: the INTENSIFY study. J Clin Med. 2023;12:4248.

Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, Fitchett D, Bluhmki E, Hantel S, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2117–28.

Yu J, Arnott C, Neuen BL, Heersprink HL, Mahaffey KW, Cannon CP, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with canagliflozin according to baseline diuretic use: a post hoc analysis from the CANVAS Program. ESC Heart Fail. 2021;8:1482–93.

Wanner C, Inzucchi SE, Lachin JM, Fitchett D, von Eynatten M, Mattheus M, et al. Empagliflozin and progression of kidney disease in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:323–34.

Mosenzon O, Wiviott SD, Cahn A, Rozenberg A, Yanuv I, Goodrich EL, et al. Effects of dapagliflozin on development and progression of kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes: an analysis from the DECLARE–TIMI 58 randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7:606–17.

Blonde L, Stenlöf K, Fung A, Xie J, Canovatchel W, Meininger G. Effects of canagliflozin on body weight and body composition in patients with type 2 diabetes over 104 weeks. Postgrad Med. 2016;128:371–80.

Bolinder J, Ljunggren Ö, Kullberg J, Johansson L, Wilding J, Langkilde AM, et al. Effects of dapagliflozin on body weight, total fat mass, and regional adipose tissue distribution in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with inadequate glycemic control on metformin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1020–31.

Neeland IJ, McGuire DK, Chilton R, Crowe S, Lund SS, Woerle HJ, et al. Empagliflozin reduces body weight and indices of adipose distribution in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2016;13:119–26.

Pratama K. Weight loss effect of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors in patients with obesity without diabetes: a systematic review. Acta Endocrinol (Bucharest). 2022;18:216–24.

Weingold R, Zinman B, Mattheus M, Ofstad AP, Steubl D, Wanner C, et al. Shifts in KDIGO CKD risk groups with empagliflozin: kidney-protection from SGLT2 inhibition across the spectrum of risk. J Diabetes Complic. 2023;37: 108628.

UK Kidney Association. UK Kidney Association clinical practice guideline: Sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibition in adults with kidney disease [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2023 Dec 19]. https://ukkidney.org/health-professionals/guidelines/ukka-clinical-practice-guideline-sodium-glucose-co-transporter-2. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

A. Menarini Farmaceutica Internazionale SRL. Invokana 300 mg film-coated tablets. Summary of product characteristics [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2023 Dec 19]. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/11409. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

Boehringer Ingelheim Limited. Jardiance 25 mg film-coated tablets. Summary of product characteristics [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 19]. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/7703/smpc. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

AstraZeneca UK Limited. Forxiga 10 mg film-coated tablets. Summary of product characteristics [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Dec 19]. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/7607/smpc. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

Merck Sharp & Dohme (UK) Limited. Steglatro 15 mg film-coated tablets. Summary of product characteristics [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Dec 19]. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/10099/smpc. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:3599–726.

Cosentino F, Grant PJ, Aboyans V, Bailey CJ, Ceriello A, Delgado V, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:255–323.

Evans M, Morgan AR, Davies S, Beba H, Strain WD. The role of sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors in frail older adults with or without type 2 diabetes mellitus. Age Ageing. 2022;51:afac201.

NHS Digital. National Diabetes Audit. Young people with Type 2 diabetes, 2019–20 [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2023 Jul 26]. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/national-diabetes-audit/young-people-with-type-2-diabetes-2019--20#top. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

TODAY Study Group, Bjornstad P, Drews KL, Caprio S, Gubitosi-Klug R, Nathan DM, et al. Long-term complications in youth-onset type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:416–26.

ClinRisk Ltd. QRISK®3-lifetime cardiovascular risk calculator [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Jul 26]. https://qrisk.org/lifetime. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

ClinRisk Ltd. Welcome to the QRISK®3-2018 risk calculator [Internet]. [cited 2023 Aug 29]. https://www.qrisk.org/. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Putting NICE guidance in to Practice. Resource impact report: type 2 diabetes in adults: management (update) [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Aug 4]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28/resources/resource-impact-report-type-2-diabetes-and-cardiovascular-risk-update-pdf-10958006557. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

Butler J, Usman MS, Filippatos G, Ferreira JP, Böhm M, Brueckmann M, et al. Safety and efficacy of empagliflozin and diuretic use in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2023;8:640.

Shen L, Kristensen SL, Bengtsson O, Böhm M, de Boer RA, Docherty KF, et al. Dapagliflozin in HFrEF patients treated with mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists: an analysis of DAPA-HF. JACC Heart Fail. 2021;9:254–64.

Peasah SK, Huang Y, Palli SR, Swart EC, Donato BM, Pimple P, et al. Real-world impact of empagliflozin on total cost of care in adults with type 2 diabetes: Results from an outcomes-based agreement. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2023;29:152–60.

Choi JG, Winn AN, Skandari MR, Franco MI, Staab EM, Alexander J, et al. First-line therapy for type 2 diabetes with sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists: a cost-effectiveness study. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175:1392–400.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Canagliflozin, dapagliflozin and empagliflozin as monotherapies for treating type 2 diabetes. Technology appraisal guidance [TA390] [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2024 Jan 17]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta390. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

Kanumilli N, Brunton S, Cos X, Deed G, Kushner P, Lin P, et al. Global survey investigating causes of treatment inertia in type 2 diabetes cardiorenal risk management. J Diabetes Complic. 2021;35: 107813.

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. SGLT2 inhibitors: updated advice on increased risk of lower-limb amputation (mainly toes) [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2023 Dec 19]. https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/sglt2-inhibitors-updated-advice-on-increased-risk-of-lower-limb-amputation-mainly-toes#:~:text=Drug%20Safety%20Update-,SGLT2%20inhibitors%3A%20updated%20advice%20on%20increased%20risk%20of%20lower%2Dlimb,may%20be%20a%20class%20effect. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. SGLT2 inhibitors: reports of Fournier’s gangrene (necrotising fasciitis of the genitalia or perineum) [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2023 Aug 7]. https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/sglt2-inhibitors-reports-of-fournier-s-gangrene-necrotising-fasciitis-of-the-genitalia-or-perineum. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

Brown P. Need to know guide: SGLT2 inhibitor indications, doses and licences (updated 2023). Diabetes Prim Care. 2023;25:9–10.

Diggle J. Ketones and diabetes. Diabetes Prim Care. 2020;22:49–50.

Wang KM, Isom RT. SGLT2 inhibitor-induced euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis: a case report. Kidney Med. 2020;2:218–21.

Umapathysivam MM, Gunton J, Stranks SN, Jesudason D. Euglycemic ketoacidosis in two patients without diabetes after introduction of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Diabetes Care. 2023;47:1–4.

Brown P. How to use SGLT2 inhibitors safely and effectively. Diabetes Prim Care. 2023;25:113–5.

Vadi S, Lad V, Kapoor D. Perioperative implication of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor in a patient following major surgery. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2021;25:958–9.

Kumar S, Bhavnani SP, Goyal P, Rich MW, Krishnaswami A. Preoperative cessation of SGLT2i [Internet]. American College of Cardiology. 2022 [cited 2023 Aug 14]. https://www.acc.org/Latest-in-Cardiology/Articles/2022/10/07/17/21/Preoperative-Cessation-of-SGLT2i. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

Dave CV, Schneeweiss S, Kim D, Fralick M, Tong A, Patorno E. Sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors and the risk for severe urinary tract infections. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:248–56.

Wilding J. SGLT2 inhibitors and urinary tract infections. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15:687–8.

Kang A, Smyth B, Neuen BL, Heerspink HJL, Di Tanna GL, Zhang H, et al. The sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor canagliflozin does not increase risk of non-genital skin and soft tissue infections in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a pooled post hoc analysis from the CANVAS Program and CREDENCE randomized double-blind trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2023;25:2151–62.

Dass AS, Immaculate G, Bhattacharyya A. Fournier’s gangrene and sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors: our experience. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2019;23:165–6.

Yang JY, Wang T, Pate V, Buse JB, Stürmer T. Real-world evidence on sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor use and risk of Fournier’s gangrene. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2020;8: e000985.

Chowdhury T, Gousy N, Bellamkonda A, Dutta J, Zaman CF, Zakia UB, et al. Fournier’s Gangrene: a coexistence or consanguinity of SGLT-2 inhibitor therapy. Cureus. 2022;14: e27773.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summary—diabetes type 2 [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 19]. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/diabetes-type-2/. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

Schaper NC, Netten JJ, Apelqvist J, Bus SA, Hinchliffe RJ, Lipsky BA. Practical Guidelines on the prevention and management of diabetic foot disease (IWGDF 2019 update). Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020;36: e3266.

See RM, Teo YN, Teo YH, Syn NL, Yip ASY, Leong S, et al. Effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 on amputation events: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Pharmacology. 2022;107:123–30.

Scheen AJ. Lower-limb amputations in patients treated with SGLT2 inhibitors versus DPP-4 inhibitors: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Diabetes Epidemiol Manag. 2022;6: 100054.

Baker N. Diabetic foot care: a guide for non-specialists. J Diabetes Nurs. 2020;24:JDN144.

Strain WD, Down S, Brown P, Puttanna A, Sinclair A. Diabetes and frailty: an expert consensus statement on the management of older adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2021;12:1227–47.

Rong X, Li X, Gou Q, Liu K, Chen X. Risk of orthostatic hypotension associated with sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor treatment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2020;17:147916412095362.

Jackson AM, Dewan P, Anand IS, Bělohlávek J, Bengtsson O, de Boer RA, et al. Dapagliflozin and diuretic use in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction in DAPA-HF. Circulation. 2020;142:1040–54.

van Ruiten CC, Hesp AC, van Raalte DH. Sodium glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors protect the cardiorenal axis: update on recent mechanistic insights related to kidney physiology. Eur J Intern Med. 2022;100:13–20.

Lam D, Shaikh A. Real-life prescribing of SGLT2 inhibitors: how to handle the other medications, including glucose-lowering drugs and diuretics. Kidney360. 2021;2:742–6.

Sawaf H, Qaz M, Ismail J, Mehdi A. The renal effects of SGLT2 inhibitors. EMJ Nephrol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.33590/emjnephrol/22-00080.

Yavin Y, Mansfield TA, Ptaszynska A, Johnsson K, Parikh S, Johnsson E. Effect of the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin on potassium levels in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a pooled analysis. Diabetes Ther. 2016;7:125–37.

Neuen BL, Oshima M, Agarwal R, Arnott C, Cherney DZ, Edwards R, et al. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and risk of hyperkalemia in people with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomized, controlled trials. Circulation. 2022;145:1460–70.

Tang J, Ye L, Yan Q, Zhang X, Wang L. Effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors on water and sodium metabolism. Front Pharmacol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.800490. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

Neuen BL, Oshima M, Perkovic V, Agarwal R, Arnott C, Bakris G, et al. Effects of canagliflozin on serum potassium in people with diabetes and chronic kidney disease: the CREDENCE trial. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:4891–901.

Zannad F, Rossignol P. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists and SGLT2 inhibitor therapy: the best of both worlds in HFrEF. JACC Heart Fail. 2021;9:265–7.

Yang S, Zhao L, Mi Y, He W. Effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors and aldosterone antagonists, in addition to renin-angiotensin system antagonists, on major adverse kidney outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2022;24:2159–68.

Mosenzon O, Alguwaihes A, Leon JLA, Bayram F, Darmon P, Davis TME, et al. CAPTURE: a multinational, cross-sectional study of cardiovascular disease prevalence in adults with type 2 diabetes across 13 countries. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2021;20:154.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Finerenone for treating chronic kidney disease in type 2 diabetes. Technology appraisal guidance. TA877 [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 19]. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta877. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

Ferreira JP, Inzucchi SE, Mattheus M, Meinicke T, Steubl D, Wanner C, et al. Empagliflozin and uric acid metabolism in diabetes: a post hoc analysis of the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2022;24:135–41.

Li J, Badve SV, Zhou Z, Rodgers A, Day R, Oh R, et al. The effects of canagliflozin on gout in type 2 diabetes: A post-hoc analysis of the CANVAS Program. Lancet Rheumatol. 2019;1:e220–8.

Lund LC, Højlund M, Henriksen DP, Hallas J, Kristensen KB. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors and the risk of gout: a Danish population-based cohort study and symmetry analysis. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2021;30:1391–5.

Zhou J, Liu X, Chou OH-I, Li L, Lee S, Wong WT, et al. Lower risk of gout in sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors versus dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) inhibitors in type-2 diabetes. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2023;62:1501–10.

Fralick M, Chen SK, Patorno E, Kim SC. Assessing the risk for gout with sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes: a population-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:186–94.

Wei J, Choi HK, Dalbeth N, Li X, Li C, Zeng C, et al. Gout flares and mortality after sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor treatment for gout and type 2 diabetes. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6: e2330885.

Down S. How to advise on sick day rules. Diabetes Prim Care. 2020;22:47–8.

Fernando K. Comparison of ADA/EASD and NICE Recommendations on the Pharmacological Management of Type 2 Diabetes In Adults [Internet]. Medscape. 2022 [cited 2023 Dec 19]. https://www.medscape.co.uk/viewarticle/primary-care-hacks-comparison-ada-easd-and-nice-2022a10024zc. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

Dashora U, Gregory R, Winocour P, Dhatariya K, Rowles S, Macklin A, et al. Association of British Clinical Diabetologists (ABCD) and Diabetes UK joint position statement and recommendations for non-diabetes specialists on the use of sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors in people with type 2 diabetes (January 2021). Clin Med (Lond). 2021;21:204–10.

Diabetes UK. Diabetes when you’re unwell [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 19]. https://www.diabetes.org.uk/guide-to-diabetes/life-with-diabetes/illness. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

International Diabetes Federation, Diabetes and Ramadan (DAR) International Alliance. Diabetes and Ramadan: Practical guidelines [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2023 Dec 19]. https://dar-safa-storage-bahrain.s3.me-south-1.amazonaws.com/IDF_Da_R_Practical_Guidelines_2021_web_166f7cbf4f.pdf. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

Hanif W, Patel V, Ali S, Karamat A, Hassanein M, Syed A, et al. The South Asian Health Foundation (UK) Guidelines for managing diabetes during Ramadan: 2020 Update [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2023 Dec 19]. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5944e54ab3db2b94bb077ceb/t/5e847ebf2c6ec1680158c373/1585741505374/Ramadan+Guidelines+Update.pdf. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

Pellicori P, Fitchett D, Kosiborod MN, Ofstad AP, Seman L, Zinman B, et al. Use of diuretics and outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes: findings from the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23:1085–93.

Lunati ME, Cimino V, Gandolfi A, Trevisan M, Montefusco L, Pastore I, et al. SGLT2-inhibitors are effective and safe in the elderly: the SOLD study. Pharmacol Res. 2022;183: 106396.

Butt JH, Jhund PS, Belohlávek J, de Boer RA, Chiang C-E, Desai AS, et al. Efficacy and safety of dapagliflozin according to frailty in patients with heart failure: a prespecified analysis of the DELIVER trial. Circulation. 2022;146:1210–24.

Goldman A, Fishman B, Twig G, Raschi E, Cukierman-Yaffe T, Moshkovits Y, et al. The real-world safety profile of sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors among older adults (≥ 75 years): a retrospective, pharmacovigilance study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22:16.

TREND Diabetes. Something you need to know: how to reduce your risk of genital fungal infection [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 19]. https://trenddiabetes.online/portfolio/something-you-need-to-know-how-to-reduce-you-risk-of-genital-fungal-infection/. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

Diabetes UK. What is DKA (diabetic ketoacidosis)? [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 19]. https://www.diabetes.org.uk/guide-to-diabetes/complications/diabetic_ketoacidosis. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

TREND Diabetes. Type 2 diabetes and ketoacidosis [Internet]. [cited 2023 Aug 10]. https://trenddiabetes.online/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/A5_DKA_TREND.pdf. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

TREND Diabetes. What to do when you are ill [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Dec 19]. https://trenddiabetes.online/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/A5_T2Illness_TREND_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

TREND Diabetes. Looking after your feet when you have diabetes [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 19]. https://trenddiabetes.online/portfolio/looking-after-your-feet-when-you-have-diabetes/. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

Centre for Perioperative Care. Guideline for perioperative care for people with diabetes mellitus undergoing elective and emergency surgery [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Dec 19]. https://cpoc.org.uk/sites/cpoc/files/documents/2022-12/CPOC-Diabetes-Guideline-Updated2022.pdf. Accessed 14 Mar 2024

Medical Writing/Editorial Assistance.

This publication has been independently developed by the Improving Diabetes Steering Committee. Medical writing services were provided on behalf of the authors by Rebecca Down at Copperfox Communications Limited and project management support was provided by Lisa Kelly at LKOTT Consulting Limited – Medical Communications. Funding for medical writing and project management support services was provided by A. Menarini Farmaceutica Internazionale SRL.

Authorship.

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Funding

A. Menarini Farmaceutica Internazionale SRL has fully funded the creation of this manuscript and has reviewed and certified it for technical accuracy (Dec 2023 | PP-NP-UK-0015). A. Menarini Farmaceutica Internazionale SRL also provided funding for the journal’s Rapid Service Fee. All authors had full access to all of the data discussed in the paper and take responsibility for the integrity of the information presented.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Samuel Seidu, Vicki Alabraba, Sarah Davies, Philip Newland-Jones, Kevin Fernando, Stephen Bain, Jane Diggle, Marc Evans, June James, Naresh Kanumilli, Nicola Milne, Adie Viljoen, David C Wheeler, and John PH Wilding devised and shaped the content for the narrative review paper. Each of the named authors reviewed and critically appraised the manuscript during development and approved the final version for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest