Abstract

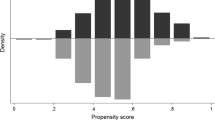

The need for and role of highly skilled immigrant workers in the U.S. economy is fiercely debated. Proponents and opponents agree that temporary foreign workers are paid a lower wage than are natives. This lower wage partly originates from the restricted mobility of workers while on a temporary visa. In this article, we estimate the wage gain to employment-based immigrants from acquiring permanent U.S. residency. We use data from the New Immigrant Survey (2003) and implement a difference-in-difference propensity score matching estimator. We find that for employer-sponsored immigrants, the acquisition of a green card leads to an annual wage gain of about $11,860.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We use the terms “green card,” “legal permanent residency (LPR),” and “permanent residency” interchangeably in this article.

Extensions on pending green card applications can alter the six-year time interval.

In our analysis, we do not distinguish between H-1B and L-1 temporary workers. Although the use of L-1 visa has increased since the late 1990s, the number of L-1 visas issued is still small compared with the number of H-1B visas even though the number of L-1 visas is not capped (Kirkegaard 2005). Given the time frame of our sample, we do not expect the share of L-1 immigrants to be particularly large in our sample. We discuss this issue further in the Data section.

Green cards may have a high nonmonetary value (e.g., utility from having relatives close-by, or peace of mind from persecution), but we do not address those issues here.

Another level of selection relates to the question of who immigrates in the first place. That selection, although important for other purposes, may not be very important here because our universe consists of only immigrants and not the whole population of the source countries.

We also implemented a cross-sectional matching on a larger sample of 863 immigrants. The summary statistics for this group are in the last four columns of Table 2.

Alternatively, we could have matched of the year of birth, which would not require this adjustment. But interpretations of coefficients of higher-order terms (like age squared) are problematic. Using year of birth yields the same results.

We did not use years of education in our baseline specification because that variable did not satisfy the balancing criterion in the cross-sectional matching sample (discussed later in this section). However, years of education does satisfy the balancing criterion in this sample, and including it in the propensity score specification does not change our estimates.

The summary statistics for this sample are presented in the last four columns of Table 2.

References

Abadie, A., & Imbens, G. (2008). On the failure of the bootstrap for matching estimators. Econometrica, 76, 1537–1557.

Becker, S. O., & Ichino, A. (2002). Estimation of average treatment effects based on propensity scores. The Stata Journal, 2, 358–377.

Borjas, G. J. (1987). Self-selection and the earnings of immigrants. American Economic Review, 77, 531–553.

Chiswick, B. R. (1980). An analysis of the economic progress and impact of immigrants (Report prepared for the Employment and Training Administration). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor.

Constant, A., & Massey, D. S. (2003). Self-selection, earnings, and out-migration: A longitudinal study of immigrants to Germany. Journal of Population Economics, 16, 631–653.

Dehejia, R., & Wabha, S. (2002). Propensity score matching methods for non-experimental causal studies. Review of Economics and Statistics, 84, 151–161.

Gass-Kandilov, A. (2007). The value of a green card: Immigrant wage increases following adjustment to U.S. permanent residence. Unpublished paper, Department of Economics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Hafner, K., & Preysman, D. (2003, May 30). Special visa’s use for tech workers is challenged. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2003/05/30/technology/30VISA.html?pagewanted=all

Hamm, S., & Herbst, M. (2009, October 12). America’s high-tech sweatshops. Businessweek. Retrieved from http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/09_41/b4150034732629.htm

Heckman, J., Ichimura, H., Smith, J., & Todd, P. (1996). Sources of selection bias in evaluating social programs: An interpretation of conventional measures and evidence on the effectiveness of matching as a program evaluation method. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 93, 13416–13420.

Heckman, J., Ichimura, H., Smith, J., & Todd, P. (1998a). Characterizing selection bias using experimental data. Econometrica, 66, 1017–1098.

Heckman, J., Ichimura, H., & Todd, P. (1997). Matching as an econometric estimator: Evidence from evaluating a job training programme. Review of Economic Studies, 64, 605–654.

Heckman, J., Ichimura, H., & Todd, P. (1998b). Matching as an econometric evaluation estimator. Review of Economic Studies, 65, 261–294.

Hersch, J. (2008). Profiling the new immigrant worker: The effects of skin color and height. Journal of Labor Economics, 26, 345–386.

Hira, R. (2007). Outsourcing America’s technology and knowledge jobs (EPI Briefing Paper No. 187). Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute. Retrieved from http://www.sharedprosperity.org/bp187.html

Jasso, G., & Rosenzweig, M. R. (1988). How well do U.S. immigrants do? Vintage effects, emigration selectivity, and occupational mobility of immigrants. In T. P. Schultz (Ed.), Research of population economics (Vol. 6, pp. 229–253). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Jasso, G., Massey, D., Rosenzweig, M. R., & Smith, J. (2000). The New Immigrant Survey Pilot: Overview and new findings about legal immigrants at admission. Demography, 37, 127–138.

Kirkegaard, J. (2005). Outsourcing and skill imports: Foreign high-skilled workers on H-1B and L-1 Visas in the United States (IIE Working Paper No. 05–15). Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics. Retrieved from http://www.iie.com/

Leuven, E., & Sianesi, B. (2003). PSMATCH2: Stata module to perform full Mahalanobis and propensity score matching, common support graphing, and covariate imbalance testing (version 3.0.0). Boston, MA: Department of Economics, Boston University. Retrieved from http://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s432001.html

Lowell, L. B. (2001). Skilled temporary and permanent immigrants in the United States. Population Research and Policy Review, 20, 33–58.

Massey, D. S. (1987). Understanding Mexican migration to the United States. American Journal of Sociology, 92, 1332–1403.

Matloff, N. (2004). Needed reform for the H-1B and L-1 work visas (and relation to offshoring) (Proposal). Davis: University of California.

Miano, J. (2007). Low salaries for low skills wages and skill levels for H-1B computer workers, 2005 (Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder 4–07). Washington, DC: Center for Immigration Studies. Retrieved from http://www.cis.org/articles/2007/back407.html

Miano, J. (2008). H-1B visa numbers: No relationship to economic need (Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder 7–08). Retrieved from http://www.cis.org/H1bVisaNumbers

National Foundation for American Policy (NFAP). (2006). H-1B professionals and wages: Setting the record straight (NFAP Policy Brief). Arlington, VA: NFAP. Retrieved from http://www.nfap.com/

National Foundation for American Policy (NFAP). (2009). H-1B visas by the numbers (NFAP Policy Brief). Arlington, VA: NFAP. Retrieved from http://www.nfap.com/

National Research Council. (2001). Building a workforce for the information economy. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Reagan, P. B., & Olsen, R. J. (2000). You can go home again: Evidence from longitudinal data. Demography, 37, 339–350.

Rosenbaum, P., & Rubin, D. (1983). The central role of the propensity score in the observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 70, 41–55.

Silverman, B. W. (1986). Density estimation for statistics and data analysis (Monographs on Statistics and Applied Probability). London, UK: Chapman and Hall.

Smith, J., & Todd, P. (2005). Does matching overcome LaLonde’s critique of non-experimental estimators? Journal of Econometrics, 125, 305–353.

Summers, R., & Heston, A. (1991). The Penn World Table (Mark 5): An expanded set of international comparisons, 1950–1988. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106, 327–368.

Todd, P. (2008). Matching estimators. In S. N. Durlauf & L. E. Blume (Eds.), The new Palgrave dictionary of economics. Palgrave Macmillan. Retrieved from http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com

U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). (2010). Yearbook of immigration statistics. Washington, DC: DHS. Retrieved from http://www.dhs.gov/

U.S. General Accounting Office. (2003). Better tracking needed to help determine H-1B program’s effects on the U.S. workforce (Report). Retrieved from http://www.gao.gov/

Wayne, L. (2001, April 29). Workers, and bosses, in a visa maze. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2001/04/29/business/workers-and-bosses-in-a-visa-maze.html?src=pm

Zavodny, M. (2003). The H-1B program and its effects on information technology workers. Economic Review, Q3, 33–43.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank two anonymous referees and the editor for many helpful comments. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mukhopadhyay, S., Oxborrow, D. The Value of an Employment-Based Green Card. Demography 49, 219–237 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-011-0079-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-011-0079-3