Abstract

Gastrointestinal involvement is a rare manifestation of systemic amyloidosis, and few reports have been published on localized amyloidosis of the colon. Only one case report has been published on the long-term prognosis of localized colorectal amyloidosis, and there are no previous reports on localized colorectal ATTR amyloidosis. Here, we report an 80-year-old male with localized colorectal wild-type ATTR amyloidosis who presented with edematous mucosa with vascular changes throughout the colon. He did not exhibit any symptoms or endoscopic exacerbation for 8 years after diagnosis. However, after 8 years, he developed early stage colorectal cancer and cytomegalovirus-associated ulcer. He was treated with endoscopic submucosal dissection, which was relatively challenging due to his hemorrhagic condition and poor elevation of the submucosa caused by amyloid deposits. Since the tumor was completely resected, he will undergo regular follow-up. Our review of 20 previous cases of localized colorectal amyloidosis revealed its clinical features and long-term prognosis. Specifically, ours is the second case of a diffuse pan-colon type of colorectal localized amyloidosis, which may lead to various complications, such as colorectal cancer, over a long period of time, and thus, regular follow-up is necessary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Amyloidosis is characterized by extracellular deposition of abnormal fibrillar proteins, which disrupt tissue structure and function [1]. AL amyloidosis (immunoglobulin light chain), ATTR amyloidosis (transthyretin), AA amyloidosis (serum amyloid A), and hemodialysis-associated amyloidosis (Aβ2 amyloid) are well-known types of amyloidosis [1]. Gastrointestinal involvement is a rare manifestation of amyloidosis, which commonly affects the heart and kidneys [1]. Gastrointestinal amyloidosis has various clinical presentations, including weight loss, chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, intestinal bleeding, and pseudo-obstruction [1, 2]. After the small intestine, the colorectum is the second most common site of gastrointestinal amyloidosis [1], but only a few studies of localized colorectal amyloidosis have been published thus far.

Although the prognosis of localized gastrointestinal amyloidosis without systemic involvement has been reported to be good [3], only one case report on the long-term prognosis of localized colorectal amyloidosis has been published [4]. Moreover, no previous reports of colorectal localized ATTR amyloidosis or endoscopic treatment of early stage colorectal cancer with a background of colorectal amyloidosis have been published.

In this study, we report the long-term, 8-year course of a case of localized colorectal wild-type ATTR amyloidosis. In this case, the patient developed localized cytomegalovirus-associated ulcer and early stage colorectal cancer, which was successfully resected endoscopically. We also aimed to review and evaluate the clinical features and long-term prognosis of localized colorectal amyloidosis.

Case presentation

An 80-year-old male with a history of hematochezia was diagnosed with localized colorectal amyloidosis by endoscopy 8 years ago. Endoscopy revealed a continuous edematous mucosa with vascular hyperplasia and vasodilatation throughout the colon (Fig. 1A–D). Histological analysis revealed submucosal amyloid deposits throughout the colon. He had a history of hyperlipidemia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and enteroscopy were performed at another hospital, but no amyloid deposits were observed histologically. Since hematochezia improved spontaneously without any treatment, only a follow-up colonoscopy was performed once a year thereafter. Endoscopic images showed that blood vessels became more irregularly dilated over time, which suggests progression of amyloidosis (Fig. 1D–F).

Endoscopic findings of colorectal amyloidosis at the time of diagnosis showing edematous mucosa with vascular changes throughout the colon and endoscopic images of colorectal localized amyloidosis over 8 years. A–D Endoscopy at the time of diagnosis showed continuous edematous mucosa with vascular hyperplasia and vasodilatation throughout the entire colon. A Ascending colon. B Transverse colon. C Sigmoid colon. D Rectum. E–F Endoscopic images of the rectum over time. Endoscopic image obtained E 4 years ago and F recently. Blood vessels became more irregularly dilated over time, which suggests progression of amyloidosis

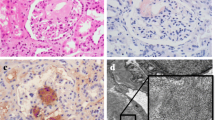

Eight years later, routine colonoscopy revealed a single punched-out ulcer in the sigmoid colon (Fig. 2A) and a 4-cm laterally spreading tumor of the non-granular type (LST-NG, flat elevated type) in the rectum (Fig. 2B–D). Simultaneously, the distribution and type of amyloid deposition were further examined. Histological analysis revealed an active cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection in the ulcer in the sigmoid colon (Supplementary Fig. 1), but no signs of CMV reactivation were observed according to blood tests (CMV-IgM, CMV-IgG, and CMV-antigenemia; Table 1). Submucosal amyloid deposits were found throughout the colon (Fig. 3A–C), and immunohistochemistry revealed that the amyloid deposits were ATTR-positive and AL- and AA-negative (Fig. 3D). The effects of amyloid on internal organs, such as the liver, heart, and kidneys, were negative according to blood tests as well as electrophoresis, urinalysis (Table 1), electrocardiogram, and echocardiogram. Computed tomography (CT) also revealed no evidence of systemic amyloidosis, such as organomegaly, including in the liver. Genetic analysis revealed no mutations in the TTR gene. Based on these results, localized, colorectal, wild-type ATTR amyloidosis was diagnosed.

Regular colonoscopy revealed a CMV-associated ulcer in the sigmoid colon and LST-NG in the rectum. A A punched-out ulcer in the sigmoid colon. B–D 4-cm laterally spreading tumor of the non-granular type (LST-NG, flat elevated type) in the rectum. B white light, C chromoendoscopy with indigo carmine, D magnifying endoscopy with narrow band imaging

Histological analysis revealed widespread amyloid deposits (ATTR) in the submucosa. A Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining revealed widespread acidophilic deposits in the submucosa. B Congo red staining revealed widespread amyloid deposits in the submucosa. C The deposits exhibit a characteristic apple-green birefringence under polarized light (Congo red under polarized light at high magnification). D Immunohistochemistry revealed ATTR-positive amyloid deposits, which suggests ATTR amyloidosis. Scale bar: A, B 2000 μm, C, D 500 μm

Endoscopic submucosal dissetion was performed for the rectal LST-NG, which was relatively challenging due to the patient’s hemorrhagic condition and poor elevation of the submucosa caused by submucosal yellowish amyloid deposits (Fig. 4A–C). The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged. The histological diagnosis was Ra, 0-IIa, 35 × 40 mm, adenocarcinoma, tub1, pTis (M), Ly0, V0, HMX, VM0 with amyloid deposits in the submucosa (Figs. 4D, 5). The cause of HMX was considered to be the partially fragmented sample at the time of collection (Fig. 4D). Therefore, the tumor was considered to be completely resected. Since the patient experienced no subjective symptoms or signs of systemic amyloidosis, we plan to perform regular follow-up of this patient.

Images of the endoscopic submucosal dissection procedure for early stage colorectal cancer in an amyloidosis background. A Distant view of the tumor after marking. B This area bled easily with a local injection and poor lifting of the submucosal layer. C The normal submucosal layer was barely visible due to yellow amyloid deposits in some areas. D Image of the excised specimen

Histological analysis of the excised specimen revealed well-differentiated intramucosal adenocarcinoma with submucosal amyloid deposits. A H&E staining at low magnification shows well-differentiated adenocarcinoma confined to the mucosa and widespread submucosal amyloid deposits. B Congo red staining revealed widespread amyloid deposits in the submucosa. C H&E staining at high magnification. D, E Immunohistochemistry for (D) Ki67 and (E) P53 suggests well-differentiated, early stage adenocarcinoma without any characteristics of colitis-associated dysplasia or cancer. Scale bar: A, B 2000 μm, C–E 500 μm

Discussion

Gastrointestinal involvement in systemic amyloidosis is rarer than heart and kidney involvement, and localized amyloidosis in the gastrointestinal tract is even less common [1]. Moreover, few reports have been published thus far on localized colorectal amyloidosis.

To assess the characteristics and prognosis of localized colorectal amyloidosis, the literature was reviewed by searching the Pubmed electronic database using the key terms “localized colon amyloidosis” or “amyloidosis” and the following words: “colon” or “rectum.” Our search yielded 589 previous studies on colorectal amyloidosis, including 20 localized colorectal amyloidosis cases (Table 2) [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. These 20 cases were histologically diagnosed as colorectal amyloidosis, and no findings suggestive of secondary amyloidosis, systemic amyloidosis, or hematological disorders, such as multiple myeloma, were reported. All cases were diagnosed with localized colorectal amyloidosis without involvement of internal organs according to blood tests and other type of tests, including electrophoresis, bone marrow examination, urinalysis, electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, and CT.

Our review revealed that the mean age at presentation was 63.3 ± 13.2 years and that most cases were male (19 cases, 90%). Common symptoms included hematochezia (15 cases, 71%), abdominal pain (6 cases, 29%), and diarrhea (2 cases, 10%), while one in five patients was asymptomatic (4 cases, 19%). The sites of amyloidosis were the sigmoid colon (11 cases, 52%), entire colorectum (4 cases, 19%), and transverse colon (2 cases, 10%). In other words, 80% of localized colorectal amyloidosis was segmental, and the pan colorectal type, especially the “diffuse pan-colon type,” as in our case, was extremely rare (2 cases). Endoscopic findings of intestinal amyloidosis generally include fine granular appearance, erosions, ulcerations, mucosal friability, hematoma, and protrusions [1, 23]. We then summarized the endoscopic findings of each case according to the general findings mentioned above. Common endoscopic findings were protrusions, including submucosal tumors (12 cases, 57%), ulcerations (6 cases, 29%), and mucosal friability (3 cases, 14%). In our case, amyloid deposits were observed in multiple areas of the submucosa, including the peri-vascular area; therefore, endoscopic findings showed edematous mucosa with mucosal friability. We could not compare endoscopic findings of localized colorectal amyloidosis with colorectal manifestations of systemic cases, since no previous report that focused on the endoscopic findings of colorectal amyloidosis, including systemic amyloidosis cases, was available. However, our review suggested no specific endoscopic characteristics of localized colorectal amyloidosis. Therefore, data on a large number of cases of colorectal amyloidosis should be collected to clarify the endoscopic difference between localized and systemic cases.

AL amyloid was the most common type of localized colorectal amyloidosis (12 cases, 58%), although information about the amyloid type was unavailable in some cases (8 cases, 38%). Interestingly, no previous report of colorectal, localized, ATTR amyloidosis was found. ATTR amyloidosis, which is a less common type of amyloidosis, is a hereditary disease caused by a transthyretin gene mutation, but it may also develop as an amyloid disease in the elderly [24]. In our case, no TTR gene mutation was present, and the patient was diagnosed with localized, wild-type, ATTR amyloidosis. Regarding treatment, 50% of patients did not require any treatment (11 cases, 52%), whereas five patients required surgical intervention (23%).

A prognosis of more than one and more than 3 years was available for only six and three cases, respectively. These cases were reported to have no exacerbation of symptoms. Localized gastrointestinal amyloidosis was reported to have a good prognosis, and it can be managed with symptomatic treatment [3]. However, the long-term prognosis of colorectal localized amyloidosis is not well established, as shown in this review. Therefore, data on a large number of cases of colorectal localized amyloidosis with long-term prognosis should be collected.

Moreover, patients with the “diffuse pan-colon type” of colorectal amyloidosis might have an increased risk of developing incidental complications over time due to its widespread nature. This is the first “diffuse pan-colon type” amyloidosis case with a long history, and colorectal cancer and CMV-associated ulcers developed in the background of amyloidosis. No previous report on the relationship between localized gastrointestinal amyloidosis and gastrointestinal cancer or CMV infection has been published. Although CMV infection and disease usually develop in immunosuppressed individuals including patients with inflammatory bowel disease [25], several CMV enteritis cases were also reported in healthy individuals [26]. Therefore, the CMV-associated ulcers in our case may have occurred coincidentally, although we need to follow-up the patient and accumulate more of the same cases. We also retrospectively evaluated images of the site, where early stage colorectal cancer was detected (Supplementary Fig. 2A, B). Although it seems that the adenoma was already present 2 years ago (Supplementary Fig. 2B), it was difficult to detect the tumor in the background of amyloidosis at that time due to the edematous mucosa with vascular hyperplasia and vasodilatation. Moreover, endoscopic procedures in these cases are sometimes difficult compared with those in healthy individuals. Therefore, it would be better to differentiate the “segmental type” from the “diffuse pan-colon type” because of the difference in the risk of long-term complications.

In conclusion, this is the first reported case of localized, colorectal, wild-type ATTR amyloidosis with a long-term course. The patient showed a “diffused pan-colon type” of amyloidosis and developed a CMV-associated ulcer and colorectal cancer with colorectal amyloidosis in the background. This review revealed that the long-term prognosis of localized colorectal amyloidosis is likely to be good, although the number of cases is limited, and the distribution of this disease may be important because of the difference in the risk of long-term complications.

Abbreviations

- Ra:

-

Rectum above the peritoneal reflection

- tub1:

-

Well differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma

- pTis (M):

-

Pathologically intramucosal tumor

- Ly:

-

Lymphatic invasion

- V:

-

Venous invasion

- HM:

-

Horizontal margin

- VM:

-

Vertical margin

References

Talar-Wojnarowska R, Jamroziak K. Intestinal amyloidosis: clinical manifestations and diagnostic challenge. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2021;30:563–70.

Alshehri SA, Hussein MRA. Primary localized amyloidosis of the intestine: a pathologist viewpoint. Gastroenterol Res. 2020;13:129–37.

Sze SF, Lam P, Lam YS, et al. Gastrointestinal: a rare cause of bloody diarrhea-gastrointestinal amyloidosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:1913.

Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Lacy MQ, et al. Localized AL amyloidosis of the colon: an unrecognized entity. Amyloid. 2003;10:36–41.

Nakazawa K, Saito Y, Yoshinaga S, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for localized amyloidosis of the sigmoid colon. Endoscopy. 2022;54:E5-e6.

Picardo S, Koro K, Seow CH. Localized gastrointestinal amyloidosis, manifesting as an isolated colonic ulcer, is a rare cause of hematochezia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:A25.

Zhao J, Zhang X, Li S. Variable endoscopic appearance of localized colorectal amyloidosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:e131–2.

Kwon YH, Kim JY, Kim JH, et al. A case of primary colon amyloidosis presenting as hematochezia. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2012;59:44–7.

Antonini F, Goteri G, Macarri G. Bleeding localized amyloidosis of the colon. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46:e13.

Ogasawara N, Kitagawa W, Obayashi K, et al. Solitary amyloidosis of the sigmoid colon featuring submucosal tumor caused hematochezia. Intern Med. 2013;52:2523–7.

Makazu M, Nakajima T. A case of localized AL amyloidosis of the sigmoid colon with lymphocytes exhibiting a premalignant status. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2013;43:767.

Tsiouris A, Neale J, Stefanou A, et al. Primary amyloid of the colon mimicking ischemic colitis. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:e12-13.

Parks RW, O’Rourke D, Bharucha H, et al. Perforation of the sigmoid colon secondary to localised amyloidosis. Ulster Med J. 2002;71:144–6.

Chen JH, Lai SJ, Tsai PP, et al. Localized amyloidosis mimicking carcinoma of the colon. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:536–7.

Matsui H, Kato T, Inoue G, et al. Amyloidosis localized in the sigmoid colon. J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:607–11.

Watanabe T, Kato K, Sugitani M, et al. A case of solitary amyloidosis localized within the transverse colon presenting as a submucosal tumor. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:644–7.

Deans GT, Hale RJ, McMahon RF, et al. Amyloid tumour of the colon. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:592–3.

Díaz Del Arco C, Fernández Aceñero MJ. Globular amyloidosis of the colon. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2018;19:96–9.

Tokoro C, Inamori M, Sekino Y, et al. Localized primary AL amyloidosis of the colon without other GI involvement. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:925–6 (discussion 927).

Hirata K, Sasaguri T, Kunoh M, et al. Solitary “amyloid ulcer” localized in the sigmoid colon without evidence of systemic amyloidosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:356–7.

Martín-Arranz E, Pascual-Turrión JM, Martín-Arranz MD, et al. Focal globular amyloidosis of the colon. An exceptional diagnosis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2010;102:555–6.

Threlkeld C, Nguyen TH. Isolated amyloidosis of the colon. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1996;96:188–90.

Hokama A, Kishimoto K, Nakamoto M, et al. Endoscopic and histopathological features of gastrointestinal amyloidosis. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;3:157–61.

Sekijima Y. Transthyretin (ATTR) amyloidosis: clinical spectrum, molecular pathogenesis and disease-modifying treatments. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86:1036–43.

Kandiel A, Lashner B. Cytomegalovirus colitis complicating inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2857–65.

Cha JM, Lee JI, Choe JW, et al. Cytomegalovirus enteritis causing ileal perforation in an elderly immunocompetent individual. Yonsei Med J. 2010;51:279–83.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Enago (www.enago.jp) for the English language review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors state that they have no conflict of interest.

Consent and confidentiality

Written informed consent was given by the patient for the publication of this manuscript. Identifying information, aside from age and sex, was removed and the images provided were anonymized to protect patient confidentiality.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

12328_2022_1628_MOESM1_ESM.jpg

Supplementary Fig. 1. Histological analysis of the punched-out ulcer revealed an active cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. (A) Low and (B) high magnification. (A, B) Scale bar: 500 μm

12328_2022_1628_MOESM2_ESM.jpg

Supplementary Fig. 2. Endoscopic changes over time at the site where early stage colorectal cancer was detected. Endoscopic images of the site where early stage colorectal cancer was detected. Endoscopic images (A) 4 years ago and (B) 2 years ago

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Watanabe, S., Uchida, H., Nanke, I. et al. A case of localized colorectal wild-type ATTR amyloidosis complicated by early stage colorectal cancer and a CMV-associated ulcer during the long-term follow-up. Clin J Gastroenterol 15, 603–610 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-022-01628-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-022-01628-2