Abstract

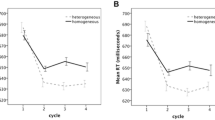

In three experiments, we examined whether similar principles apply to written and spoken production. Using a blocked cyclic written picture naming paradigm, we replicated the semantic interference effects previously reported in spoken production (Experiment 1). Using a written spelling-to-dictation blocked cyclic naming task, we also demonstrated that these interference effects disappear when the task does not require semantically-mediated lexical selection (Experiment 2). Results are parallel to those reported for the analogous spoken production task of reading aloud. Similar results were observed in written spelling to dictation regardless of whether stimuli consisted of words with high or low probability phoneme-to-grapheme correspondences (Experiment 3) revealing the important role of non-semantically-mediated spelling routes in written word production. Overall, our results support the view that similar mechanisms underlie written and spoken production. This includes an incremental learning mechanism underlying semantically-mediated lexical selection that produces long-lived interference effects when multiple semantically similar items are repeatedly named.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Some authors have also drawn a parallel to the memory literature concerning retrieval-induced forgetting, whereby participants show reduced recall of previously studied items if they are forced to “actively” retrieve other semantically related items in response to cues between the study and test phases but not if they simply read related words (e.g., Anderson, 2003). According to such an account, it is “active” retrieval that leads to interference. Extending this explanation to the language domain, semantic interference may be seen in picture naming but not in reading aloud because picture naming requires “active” lexical retrieval but reading aloud does not (e.g., Navarrete et al., 2010, 2014, 2016; Oppenheim et al., 2010). Under this explanation, one could consider “active” retrieval to mean semantically-mediated lexical selection.

Note that the concepts of regularity and consistency are not exactly the same (e.g., Bonin et al., 2001; Jared, 2002; Lee, Tsai, Su, Tzeng, & Hung, 2005). Regularity is defined in terms of grapheme-to-phoneme correspondences (e.g., Coltheart et al., 2001). Words that have highly probable correspondences are considered regular (e.g., CAT), while those that do not are considered irregular/exception words whose spellings must be retrieved from long-term memory (e.g., YACHT). Regularity is sometimes treated as a categorical concept: if even one of the correspondences in a word is low probability, the word is irregular. On the other hand, consistency refers to broader orthography–phonology mappings (e.g., Peereman & Content, 1999; Seidenberg & McClelland, 1989). The patterns of letters in consistent words are always pronounced the same way (e.g., -UST in DUST), whereas the patterns of letters in inconsistent words have multiple possible pronunciations (e.g., -INT in MINT and PINT). Consistency is sometimes treated as a more graded measure. Overall, it is difficult to disentangle regularity and consistency in alphabetic languages. In the current work, we will manipulate phoneme-to-grapheme correspondences and refer to this as a manipulation of regularity.

As in reading aloud, one could consider semantically-mediated lexical selection to be “active” retrieval. In accordance with the parallels between the memory and language literatures drawn previously, one would again expect to see semantic interference for written picture naming but not written spelling to dictation since written picture naming requires “active” retrieval but written spelling to dictation does not.

Across the studies reported here, similar results were obtained for models including raw and log-transformed response times.

Note that similar results were obtained in Experiments 2 and 3 when response time was measured from the beginning of each recording (including the added silence) regardless of whether the real acoustic duration of the word was taken into account.

References

Afonso, O., & Álvarez, C. J. (2011). Phonological effects in handwriting production: Evidence from the implicit priming paradigm. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 37, 1474–1483. doi:10.1037/a0024515.

Alario, F.-X., De Cara, B., & Ziegler, J. C. (2007). Automatic activation of phonology in silent reading is parallel: Evidence from beginning and skilled readers. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 97, 205–219. doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2007.02.001.

Anderson, M. C. (2003). Rethinking interference theory: Executive control and the mechanisms of forgetting. Journal of Memory and Language. doi:10.1016/j.jml.2003.08.006.

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67, 1–48. doi:10.18637/jss.v067.i01.

Belke, E. (2008). Effects of working memory load on lexical–semantic encoding in language production. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 15, 357–363. doi:10.3758/PBR.15.2.357.

Belke, E. (2013). Long-lasting inhibitory semantic context effects on object naming are necessarily conceptually mediated: Implications for models of lexical–semantic encoding. Journal of Memory and Language, 69, 228–256. doi:10.1016/j.jml.2013.05.008.

Belke, E., Brysbaert, M., Meyer, A. S., & Ghyselinck, M. (2005a). Age of acquisition effects in picture naming: Evidence for a lexical–semantic competition hypothesis. Cognition, 96, 45–54. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2004.11.006.

Belke, E., Meyer, A. S., & Damian, M. F. (2005b). Refractory effects in picture naming as assessed in a semantic blocking paradigm. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section A, 58, 667–692. doi:10.1080/02724980443000142.

Belke, E., & Stielow, A. (2013). Cumulative and non-cumulative semantic interference in object naming: Evidence from blocked and continuous manipulations of semantic context. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 66, 2135–2160. doi:10.1080/17470218.2013.775318.

Bonin, P., Chalard, M., Méot, A., & Fayol, M. (2002). The determinants of spoken and written picture naming latencies. British Journal of Psychology, 93, 89–114. doi:10.1348/000712602162463.

Bonin, P., Collay, S., Fayol, M., & Méot, A. (2005). Attentional strategic control over nonlexical and lexical processing in written spelling to dictation in adults. Memory & Cognition, 33, 59–75. doi:10.3758/BF03195297.

Bonin, P., & Fayol, M. (2000). Writing words from pictures: What representations are activated, and when? Memory & Cognition, 28, 677–689. doi:10.3758/BF03201257.

Bonin, P., Fayol, M., & Peereman, R. (1998). Masked form priming in writing words from pictures: Evidence for direct retrieval of orthographic codes. Acta Psychologica, 99, 311–328. doi:10.1016/S0001-6918(98)00017-1.

Bonin, P., Méot, A., Lagarrigue, A., & Roux, S. (2015). Written object naming, spelling to dictation, and immediate copying: Different tasks, different pathways? Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 68, 1268–1294. doi:10.1080/17470218.2014.978877.

Bonin, P., Méot, A., Millotte, S., & Barry, C. (2013). Individual differences in adult handwritten spelling-to-dictation. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 1–11. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00402.

Bonin, P., Peereman, R., & Fayol, M. (2001). Do phonological codes constrain the selection of orthographic codes in written picture naming? Journal of Memory and Language, 45, 688–720.

Bonin, P., Roux, S., Barry, C., & Canell, L. (2012). Evidence for a limited-cascading account of written word naming. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 38, 1741–1758. doi:10.1037/a0028471.

Breining, B. L., Nozari, N., & Rapp, B. C. (2016). Does segmental overlap help or hurt? Evidence from blocked cyclic naming in spoken and written production. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 23, 500–506. doi:10.3758/s13423-015-0900-x.

Brown, A. S. (1981). Inhibition in cued retrieval. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning & Memory, 7, 204–215. doi:10.1037//0278-7393.7.3.204.

Buchwald, A., & Rapp, B. C. (2009). Distinctions between orthographic long-term memory and working memory. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 26, 724–751. doi:10.1080/02643291003707332.

Caramazza, A., & Hillis, A. E. (1990). Where do semantic errors come from? Cortex, 26, 95–122.

Coltheart, M. (1981). The MRC Psycholinguistic Database. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 33A, 497–505.

Coltheart, M., Rastle, K., Perry, C., Langdon, R., & Ziegler, J. C. (2001). DRC: A dual route cascaded model of visual word recognition and reading aloud. Psychological Review, 108, 204–256. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.108.1.204.

Cousineau, D. (2005). Confidence intervals in within-subject designs: A simpler solution to Loftus and Masson’s method. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 1, 42–45. doi:10.20982/tqmp.01.1.p042.

Crowther, J. E., & Martin, R. C. (2014). Lexical selection in the semantically blocked cyclic naming task: The role of cognitive control and learning. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 1–20. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00009.

Damian, M. F., & Als, L. C. (2005). Long-lasting semantic context effects in the spoken production of object names. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 31, 1372–1384. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.31.6.1372.

Damian, M. F., Vigliocco, G., & Levelt, W. J. M. (2001). Effects of semantic context in the naming of pictures and words. Cognition, 81, B77–B86. doi:10.1016/S0010-0277(01)00135-4.

Delattre, M., Bonin, P., & Barry, C. (2006). Written spelling to dictation: Sound-to-spelling regularity affects both writing latencies and durations. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 32, 1330–1340. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.32.6.1330.

Ellis, A. W., & Young, A. W. (1988). Human Cognitive Neuropsychology. Hove, UK: Erlbaum.

Fischer-Baum, S., Dickson, D. S., & Federmeier, K. D. (2014). Frequency and regularity effects in reading are task dependent: Evidence from ERPs. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 29, 1–14. doi:10.1080/23273798.2014.927067.

Fischer-Baum, S., & Rapp, B. (2012). Underlying cause(s) of letter perseveration errors. Neuropsychologia, 50, 305–318. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.12.001.

Folk, J. R., Rapp, B., & Goldrick, M. (2002). The interaction of lexical and sublexical information in spelling: What’s the point? Cognitive Neuropsychology, 19, 653–671. doi:10.1080/02643290244000184.

Fry, E. (2004). Phonics: A large phoneme–grapheme frequency count revised. Journal of Literacy Research, 36, 85–98.

Goldrick, M., Folk, J. R., & Rapp, B. C. (2010). Mrs. Malaprop’s neighborhood: Using word errors to reveal neighborhood structure. Journal of Memory and Language, 62, 113–134. doi:10.1016/j.jml.2009.11.008.

Goodman, R. A., & Caramazza, A. (1986). Aspects of the spelling process: Evidence from a case of acquired dysgraphia. Language and Cognitive Processes, 1, 236–296.

Goodman-Schulman, R. (1988). Orthographic ambiguity: Comments on Baxter and Warington. Cortex, 24, 129–135.

Hanna, P. R., Hanna, J. S., Hodges, R. E., & Rudorf, E. H. (1966). Phoneme–grapheme correspondences as cues to spelling improvement. Washington, DC: US Department of Health, Education and Welfare.

Hillis, A. E., & Caramazza, A. (1991). Mechanisms for accessing lexical representations for output: Evidence from a category-specific semantic deficit. Brain and Language, 40, 106–144. doi:10.1016/0093-934X(91)90119-L.

Howard, D., Nickels, L., Coltheart, M., & Cole-Virtue, J. (2006). Cumulative semantic inhibition in picture naming: Experimental and computational studies. Cognition, 100, 464–482. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2005.02.006.

Humphreys, G. W., Evett, L., & Taylor, D. (1982). Automatic phonological priming in visual word recognition. Memory & Cognition, 10, 576–590. doi:10.3758/BF03202440.

Janssen, N., Carreiras, M., & Barber, H. A. (2011). Electrophysiological effects of semantic context in picture and word naming. NeuroImage, 57, 1243–1250. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.05.015.

Jared, D. (2002). Spelling-sound consistency and regularity effects in word naming. Journal of Memory and Language, 46, 723–750. doi:10.1006/jmla.2001.2827.

Kroll, J. F., & Stewart, E. (1994). Categorical interference in translation and picture naming: Evidence for asymmetric connections between bilingual memory representations. Journal of Memory and Language, 33, 149–174.

Kucera, H., & Francis, W. N. (1967). Computational analysis of present-day American English. Providence: Brown University Press.

Landauer, T. K., Foltz, P., & Laham, D. (1998). An introduction to latent semantic analysis. Discourse Processes, 25, 259–284. doi:10.1080/01638539809545028.

McCloskey, M., Macaruso, P., & Rapp, B. (2006). Graphemeto-lexeme feedback in the spelling system: Evidence from a dysgraphic patient. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 23, 278–307. doi:10.1080/02643290442000518.

Miceli, G., & Capasso, R. (1997). Semantic errors as neuropsychological evidence for the independence and the interaction of orthographic and phonological word forms. Language and Cognitive Processes, 12, 733–764. doi:10.1080/016909697386673.

Mirman, D. (2014). Growth curve analysis and visualization using R. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC Press.

Mulatti, C., Peressotti, F., Job, R., Saunders, S., & Coltheart, M. (2012). Reading aloud: The cumulative lexical interference effect. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 19, 662–667. doi:10.3758/s13423-012-0269-z.

Navarrete, E., Del Prato, P., Peressotti, F., & Mahon, B. Z. (2014). Lexical retrieval is not by competition: Evidence from the Blocked Naming Paradigm. Journal of Memory and Language, 76, 253–272. doi:10.1016/j.jml.2014.05.003.

Navarrete, E., Mahon, B. Z., & Caramazza, A. (2010). The cumulative semantic cost does not reflect lexical selection by competition. Acta Psychologica, 134, 279–289. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2010.02.009.

Navarrete, E., Mahon, B. Z., Lorenzoni, A., & Peressotti, F. (2016). What can written-words tell us about lexical retrieval in speech production? Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1–12. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01982.

Nickels, L. (2001). Spoken word production. In B. Rapp (Ed.), The handbook of cognitive neuropsychology: What deficits reveal about the human mind (pp. 291–320). Philadelphia: Psychology Press.

Nozari, N., Freund, M., Breining, B. L., Rapp, B. C., & Gordon, B. (2016). Cognitive control during selection and repair in word production. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 31, 886–903. doi:10.1080/23273798.2016.1157194.

Oppenheim, G. M., Dell, G. S., & Schwartz, M. F. (2010). The dark side of incremental learning: A model of cumulative semantic interference during lexical access in speech production. Cognition, 114, 227–252. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2009.09.007.

Paap, K. R., & Noel, R. W. (1991). Dual-route models of print to sound: Still a good horse race. Psychological Research, 53, 13–24. doi:10.1007/BF00867328.

Patterson, K. (1986). Lexical but nonsemantic spelling? Cognitive Neuropsychology, 3, 341–367.

Peereman, R., & Content, A. (1999). LEXOP: A lexical database providing orthography–phonology statistics for French monosyllabic words. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 31, 376–379. doi:10.3758/BF03207735.

Lee, C. Y., Tsai, J. L., Su, E. C. I., Tzeng, O. J. L., & Hung, D. L. (2005). Consistency, regularity, and frequency effects in naming chinese characters. Language and Linguistics, 6, 75–107. www.ling.sinica.edu.tw/files/publication/j2005_1_03_9113.pdf.

R Core Team. (2016). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org/.

Rapp, B. C., Benzing, L., & Caramazza, A. (1997). The autonomy of lexical orthography. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 14, 71–104. doi:10.1080/026432997381628.

Rapp, B. C., & Caramazza, A. (1997). The modality-specific organization of grammatical categories: Evidence from impaired spoken and written sentence production. Brain and Language, 286, 248–286. doi:10.1006/brln.1997.1735.

Rapp, B. C., Epstein, C., & Tainturier, M.-J. (2002). The integration of information across lexical and sublexical processes in spelling. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 19, 1–29. doi:10.1080/0264329014300060.

Rastle, K., & Brysbaert, M. (2006). Masked phonological priming effects in English: Are they real? Do they matter? Cognitive Psychology, 53, 97–145. doi:10.1016/j.cogpsych.2006.01.002.

Roeltgen, D. P., Rothi, L. J. G., & Heilman, K. M. (1986). Linguistic semantic agraphia: A dissociation of the lexical spelling system from semantics. Brain and Language, 27, 257–280. doi:10.1016/0093-934X(86)90020-9.

Schnur, T. T. (2014). The persistence of cumulative semantic interference during naming. Journal of Memory and Language, 75, 27–44. doi:10.1016/j.jml.2014.04.006.

Schnur, T. T., Schwartz, M. F., Brecher, A., & Hodgson, C. (2006). Semantic interference during blocked-cyclic naming: Evidence from aphasia. Journal of Memory and Language, 54, 199–227. doi:10.1016/j.jml.2005.10.002.

Seidenberg, M. S., & McClelland, J. L. (1989). A distributed, developmental model of word recognition and naming. Psychological Review, 96, 523–568. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.96.4.523.

Shen, X. R., Damian, M. F., & Stadthagen-Gonzalez, H. (2013). Abstract graphemic representations support preparation of handwritten responses. Journal of Memory and Language, 68, 69–84. doi:10.1016/j.jml.2012.10.003.

Snodgrass, J. G., & Vanderwart, M. (1980). A standardized set of 260 pictures: Norms for name agreement, image agreement, familiarity, and visual complexity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning & Memory, 6, 174–215. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.6.2.174.

Tainturier, M.-J., Moreaud, O., David, D., Leek, E. C., & Pellat, J. (2001). Superior written over spoken picture naming in a case of frontotemporal dementia. Neurocase, 7, 89–96. doi:10.1093/neucas/7.1.89.

Tainturier, M.-J., & Rapp, B. C. (2001). The spelling process. In B. C. Rapp (Ed.), The handbook of cognitive neuropsychology: What deficits reveal about the human mind (pp. 263–290). Philadelphia: Psychology Press.

Wheeldon, L., & Monsell, S. (1994). Inhibition of spoken word production by priming a semantic competitor. Journal of Memory and Language, 33, 332–356. doi:10.1006/jmla.1994.1016.

Zhang, Q., & Damian, M. F. (2010). Impact of phonology on the generation of handwritten responses: Evidence from picture-word interference tasks. Memory & Cognition, 38, 519–528. doi:10.3758/MC.38.4.519.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the support provided by NIH Grant DC006740 for the investigation of the neural and cognitive bases of post-stroke recovery in dysgraphia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Breining, B., Rapp, B. Investigating the mechanisms of written word production: insights from the written blocked cyclic naming paradigm. Read Writ 32, 65–94 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-017-9742-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-017-9742-4