Abstract

We examine whether delays in the expected release of annual earnings have implications for the future auditor-client relationship. Managers have strong incentives to release earnings on schedule, and auditors play an important role in helping their clients avoid costly earnings announcement delays. We find an increased likelihood of subsequent auditor-client realignments after earnings announcement delays. We further find that clients changing auditors realign with audit firms that better meet their earnings announcement timing demands, without finding evidence of a significant compromise in the reliability of the financial statement numbers in the earnings announcement. Our results help inform regulatory concerns about audit market concentration and how audit firm turnover has the potential to impact the auditor-client dynamic. While it is possible that auditor turnover could lead to a power imbalance where clients gain leverage in the relationship, our results suggest otherwise.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The enactment of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act triggered the requirement of an audit of internal controls over financial reporting for accelerated filers and the creation of the PCAOB. The PCAOB has issued numerous auditing standards that have resulted in increased audit effort, such as Auditing Standard (AS) 2 (subsequently superseded by AS 5), which related to internal controls over financial reporting; AS 7, which related to the nature and extent of the engagement quality review; and AS 3 and AS 8–16, which related to risk assessment procedures and the sufficiency and evaluation of audit evidence.

Specifically, the GAO and the Advisory Committee on the Audit Profession (ACAP) highlighted the importance of the Big 4 firms managing risk in their client portfolio and the need for lower-tiered firms to emerge as viable alternatives that provide high-quality audits for public companies.

The bargaining power of larger public companies would potentially be constrained, given the smaller pool of potential audit firm candidates. In GAO surveys of large public companies issued in 2003 and 2008, 82–94% of respondents indicated that they would not consider using a non-Big 4 firm (GAO 2003, 2008). Even changes among the Big 4 firms may be limited, given that large public companies tend to use the larger accounting firms for advisory and other work, which their auditor is prohibited from providing following the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX).

In a supplemental set of exploratory analyses, we also examine the set of companies that choose to retain their auditor following an earnings announcement delay. In the first and second years after appointing the new auditor, we find that audits are more complete at the earnings announcement date and observe no difference in financial reporting/audit quality. This suggests that the earnings announcement delays were shorter and that the new auditors took actions to meet the client’s demand for timely and reliable earnings.

Chambers and Penman (1984) identify a sample of companies that released earnings later than expected. They use the number of days between the fiscal-year end and the earnings announcement date in the previous year to determine the expected earnings announcement date in the current year.

Following accounting-related issues, other cited reasons for delay include business events (approximately 20%) and accounting rule changes (approximately 7%).

Steinhoff, a PwC client, is an anecdote of delaying earnings due to auditing complexities and increased audit work. See https://www.accountingtoday.com/articles/steinhoff-delays-earnings-report-over-audit-complexities.

In our main analyses we remove auditor resignations from our sample to focus on client demands for reporting timeliness and quality. In additional untabulated analyses, we incorporate auditor resignations and examine the influence of EA delays on auditor resignations. We find that short EA delays are positively (marginally) associated with future auditor resignations (whether including or excluding auditor dismissals from the sample). Although auditors are more likely to resign from a client following a short EA delay, they are not more likely to resign following longer delays. We also find that clients are more likely to shift from one Big N auditor to another Big N auditor in response to an auditor resignation.

We use the length of time in days to the expected rather than the actual earnings announcement date to capture clients’ expected release of earnings and to avoid confounding effects with our variable of interest.

Instances where net income is different per the database are then hand-verified by examining the 8-K and 10-K filing to ensure that they are actually EA revisions rather than rounding differences.

Prior research examining EA delays typically uses the prior year’s EA release date as the expectation and classifies delays as cases where the current year EA is later than the previous year’s EA. As a robustness test we redefine EA Delay consistent with this approach. In untabulated analyses, we find results consistent with our primary analyses reported later in the paper.

Verified and tentative earnings announcement date changes include WSH codes DVV, DVT, DTV and DTT.

In untabulated tests, inferences are consistent if we include these observations in the sample.

In untabulated tests, inferences are consistent if we include auditor resignations (976 company-year observations) in the sample and examine auditor changes (dismissals and resignations) holistically. In Subsection 4.3.3, we incorporate auditor resignations back into our sample and examine the implications of earnings announcement delays on auditor resignations.

We note that certain variables exhibit the influence of outliers despite our procedure to winsorize continuous variables at the 1/99% levels (based on standard deviations, means, and interquartile ranges). To determine the extent to which potential outliers influence our results, in additional untabulated analyses we reperform our tests after further winsorizing certain variables at the 5/95% level within the respective sample distributions (Leverage and ΔAudit Fees in our sample to test H1, and OCF, σCASHREV, and σCFO in our sample to test H2). After further winsorization of these variables, sample distributions appear more reasonable, in that the sample mean for these variables now falls within the first and third quartiles of the sample distribution and all results are consistent with those in our main analyses. This suggests that outliers are not unduly influencing our results.

Variance inflation factors for tests of H1 are 3.9 or lower suggesting no multicollinearity concerns.

In untabulated analyses, we find similar results if we remove 37 auditor dismissal observations that were included in the ‘auditor company disagreement’ or ‘auditor letter disagreement’ categories from Table 4 Panel A.

We examined the actual 8-K disclosures for all auditor dismissals in the ‘other’ category and found one dismissal where the disclosure stated that communication and coordination inefficiencies related to the auditor not being located close to the client was the reason for the auditor change.

The odds ratio for EA Delay > 7 days in column (1) is 1.313 (untabulated). Thus, holding other predictor variables fixed, the odds of auditor dismissal for firms with an earnings announcement delay of at least seven days is 31.3% higher than the odds of auditor dismissal for firms without an earnings announcement delay.

We identify these predicted probabilities of Dismissal when EA Delay equals one/zero using the ‘mtable’ command in Stata.

Variance inflation factors for tests of H2 are six or lower, suggesting no multicollinearity concerns.

We find similar inferences if we expand the sample to include company-year observations that did not experience an EA delay in the previous three years.

We find that the results for models (2) and (3) are robust to specifying all control variables as levels and incorporating first-differences of the continuous control variables (SIZE, ROA, LEVERAGE, MTB, and ARINV). We also find that the results are robust to a levels specification of all discrete control variables, removing the levels continuous control variables and incorporating first-difference changes of the continuous control variables (SIZE, ROA, LEVERAGE, MTB, and ARINV). In these alternative specifications, the only difference we note relates to firms that retain their auditor following a delay. For these firms, we only find evidence of a more complete audit at the earnings announcement date in the first year following the delay.

In untabulated analyses, we decompose our earnings announcement quality variable into its two components—earnings revisions and restatements of subsequently issued financial statements containing the earnings announcement information. We find similar insignificant results across both aspects of quality.

To mitigate the potential concern that our non-result on reporting reliability is attributable to low power, we use the power one mean function in Stata to estimate the required sample size needed to detect a change of 0.5% or less in the dependent variable (EA Revision or Restate). This procedure suggests that our sample size is more than sufficient to detect this small difference in our dependent variable. While this could suggest that the insignificant results we report are attributable to the absence of a detectable signal rather than insufficient test power, we recognize that there is no perfect statistical test to demonstrate sufficient power to reject a null hypothesis. Prior research recommends considering the breadth of the confidence interval (Hoenig and Heisey 2001; Cunningham, Li, Stein, and Wright 2019). In our EA quality test, the 95% confidence interval for the variable of interest, Dismiss After EA Delay, ranges from −0.498 to 0.559. The standard deviation of EA Revision or Restate for the same sample is 0.212. This comparison suggests that the potential effect size ranges from a 2.352 standard deviation decrease to a 2.643 standard deviation increase in EA Revision or Restate. Given the breadth of the confidence interval, we recommend caution in interpreting this to mean that no effect exists.

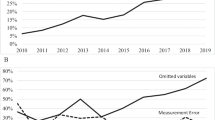

To determine if other events affecting audit report lags are influencing the results of our tests, we re-estimate our test of H1 and H2 splitting the sample into three periods: 2005–2007, 2008–2010, and 2011–2015. For the test of H1, we find similar results to our main analysis across all three sample periods. For the test of change in EA lag, the results are statically negative in the 2005–2007 and 2011–2015 periods and directionally consistent (although not statistical at conventional levels) in the 2008–2010 period. For the test of change in audit completeness at the EA date, the results are statically negative in the 2005–2007 period and insignificant in the 2008–2010 (although we recognize that this sample period only comprises firm-years ending prior to June 2009 and as such likely lacks power given the small sample size). For the likelihood of an EA delay test, the result is negative and significant in the 2011–2015 sample period but insignificant in the earlier subsample periods. The EA quality tests are insignificant across all three periods. Taken together, the results do not suggest that other events occurring during the sample period are unduly affecting our inferences.

Current non-Big N partners that formerly worked at Big N firms “perceive that Big 4 firms tend to have greater administration [and] bureaucracy,” and that non-Big N structures are “more nimble, easier to do business with when it comes to client acceptance and engagement administration” (Hux and Zimmerman 2020, 25–26).

Although we find some limited evidence of a negative reaction to the auditor change disclosure for the short delay group (in the 0, +2 window), the market does not appear to react to the missed EA or the actual EA following the short delay.

In untabulated analyses we decompose our EA quality variable into its two components—earnings revisions and restatements of subsequently issued financial statements containing the EA information. For delayed EAs, we find that the higher quality is driven primarily by a lower likelihood of subsequent restatements.

Results are similar if we limit the sample to fiscal years ending on or before June 2009 when the convention for dating the audit report changed to the 10-K filing date.

We use the propensity scores from the first-stage regression to match, without replacement, each company-year observation that has an EA delay with the company-year observation that does not have an EA delay from the same industry and year with the closest predicted value (using a maximum distance of 0.1%). We perform a similar procedure to obtain a PSM sample for our second hypothesis, where our first stage model includes all control variables in equations (2) and (3) with the exception of ΔExpected EA Lag.

For the PSM sample used to test H1, we only find a significant difference in one of the 14 matched covariates (the average change in audit fees). We find differences in the median values in four of the 14 matched covariates (i.e., Expected EA Lag, BTM, Tenure, and ΔAudit Fees), and these differences appear to be economically small. For the PSM sample used to test H2, we only find significant differences in mean change in audit fees, and this difference appears to be economically small. We find differences in the median values of Size, ROA, and OCF, and these differences appear to be economically small. Differences in medians are based on two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann-Whitney) tests.

References

Abbott, L.J., S. Parker, and G.F. Peters. 2004. Audit committee characteristics and restatements. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 23 (1): 69–87.

Abernathy, J.L., B. Beyer, A. Masli, and C. Stefaniak. 2014. The association between characteristics of audit committee accounting experts, audit committee chairs, and financial reporting timeliness. Advances in Accounting, incorporating Advances in International Accounting 30: 283–297.

Advisory Committee on the Auditing Profession (ACAP). (2008). Final report of the advisory committee on the auditing profession to the U.S. Department of the Treasury. Available at: https://www.treasury.gov/about/organizational-structure/offices/documents/final-report.pdf

Armstrong, C.S., A.D. Jagolinzer, and D.F. Larcker. 2010. Chief executive officer equity incentives and accounting irregularities. Journal of Accounting Research 48 (2): 225–271.

Ashbaugh, H., R. LaFond, and B.W. Mayhew. 2003. Do nonaudit services compromise auditor independence? Further evidence. The Accounting Review 78 (3): 611–639.

Ayers, D. R., T. L. Neal, L. C. Reid, and J. E. Shipman. (2018). Auditing goodwill in the post-amortization era: Challenges for auditors. Forthcoming, Contemporary Accounting Research.

Bagnoli, M., W. Kross, and S. Watts. 2002. The information in management's expected earnings report date: A day late, a penny short. Journal of Accounting Research 40 (5): 1275–1296.

Balachandran, B.V., and R.T.S. Ramakrishnan. 1987. A theory of audit partnerships: Audit firm size and fees. Journal of Accounting Research 25 (1): 111–126.

Bamber, E.M., L.S. Bamber, and M.P. Schoderbek. 1993. Audit structure and other determinants of audit report lag: An empirical analysis. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 12 (Spring): 1–23.

Becker, C., M. DeFond, J. Jiambalvo, and K. Subramanyam. 1998. The effect of audit quality on earnings management. Contemporary Accounting Research 15 (1): 1–24.

Beneish, M.D., P.E. Hopkins, I.P. Jansen, and R.D. Martin. 2005. Do auditor resignations reduce uncertainty about the quality of firms’ financial reporting? Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 24 (5): 357–390.

Beyer, A., D.A. Cohen, T.Z. Lys, and B.R. Walther. 2010. The financial reporting environment: Review of the recent literature. Journal of Accounting and Economics 50 (2–3): 296–343.

Bhaskar, L. S., P. E. Hopkins, and J. H. Schroeder. (2019). An investigation of auditors’ judgments when companies release earnings before audit completion. Journal of Accounting Research, Forthcoming.

Blankley, A.I., D.N. Hurtt, and J.E. MacGregor. 2012. Abnormal audit fees and restatements. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 31 (1): 79–96.

Boone, J.P., I.K. Khurana, and K.K. Raman. 2010. Do the big 4 and the second-tier firms provide audits of similar quality? Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 29 (4): 330–352.

Bronson, S.N., J.V. Carcello, C.W. Hollingsworth, and T.L. Neal. 2009. Are fully independent audit committees really necessary? Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 28 (4): 265–280.

Bronson, S.N., C.E. Hogan, M.F. Johnson, and K. Ramesh. 2011. The unintended consequences of PCAOB auditing standard Nos. 2 and 3 on the reliability of preliminary earnings releases. Journal of Accounting and Economics 51 (1–2): 95–114.

Bronson, S.N., A. Masli, and J.H. Schroeder. 2021. Releasing earnings when the audit is less complete: Implications for audit quality and the auditor/client relationship. Accounting Horizons. 35 (2): 27–55.

Cao, Y., L.A. Myers, and T.C. Omer. 2012. Does company reputation matter for financial reporting quality? Evidence from restatements. Contemporary Accounting Research 29 (3): 956–990.

Carcello, J.V., and A. Nagy. 2004. Audit firm tenure and fraudulent financial reporting. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 23 (2): 55–69.

Carcello, J.V., and T.L. Neal. 2003. Audit committee characteristics and auditor dismissals following “new” going-concern reports. The Accounting Review 78 (1): 95–117.

Cassell, C. A., J. Hansen, L. A. Myers, and T. A. Seidel. (2017). Does the timing of auditor changes affect audit quality? Evidence from the initial year of the audit engagement. Forthcoming, Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance.

Chambers, A., and S. Penman. 1984. Timeliness of reporting and the stock price reaction to earnings announcements. Journal of Accounting Research 22 (1): 21–47.

Chapman, K. 2018. Earnings notifications, investor attention, and the earnings announcement premium. Journal of Accounting and Economics 66 (1): 222–243.

Christensen, B.E., S.M. Glover, T.C. Omer, and M.K. Shelley. 2016. Understanding audit quality: Insights from audit professionals and investors. Contemporary Accounting Research 33 (4): 1648–1684.

Cunningham, L.M., C. Li, S.E. Stein, and N.S. Wright. 2019. What’s in a name? Initial evidence of U.S. audit partner identification using difference-in-differences analyses. The Accounting Review 94 (5): 139–163.

Dechow, P.M., R.G. Sloan, and A.P. Sweeney. 1996. Causes and consequences of earnings manipulation: An analysis of firms subject to enforcement actions by the SEC. Contemporary Accounting Research 13 (1): 1–36.

DeFond, M., and J. Jiambalvo. 1994. Debt covenant violation and manipulation of accruals. Journal of Accounting and Economics 17 (1–2): 145–176.

DeFond, M., and K.R. Subramanyam. 1998. Auditor changes and discretionary accruals. Journal of Accounting and Economics 25 (1): 35–67.

Dichev, I.D., J.R. Graham, C.R. Harvey, and S. Rajgopal. 2013. Earnings quality: Evidence from the field. Journal of Accounting and Economics 56 (2–3): 1–33.

Duarte-Silva, T., C.F. Noe, and K. Ramesh. 2013. How do investors interpret announcements of earnings delays? Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 25 (1): 64–71.

Einhorn, E., and A. Ziv. 2008. Intertemporal dynamics of corporate voluntary disclosures. Journal of Accounting Research 46 (3): 567–589.

Ettredge, M., J. Heintz, C. Li, and S. Scholz. 2011. Auditor realignments accompanying implementation of SOX 404 ICFR reporting requirements. Accounting Horizons 25 (1): 17–39.

Ettredge, M., C. Li, and S. Scholz. 2007. Audit fees and auditor dismissals in the Sarbanes-Oxleyera. Accounting Horizons 21 (4): 371–386.

Glover, S., J. Hansen, and T. Seidel. (2020). How has the change in the way auditors determine the audit report date changed the meaning of the audit report date? Implications for academic research. Working paper, Brigham Young University and Weber State University.

Haislip, J.Z., L.A. Myers, S. Scholz, and T.A. Seidel. 2017. The consequences of audit-related earnings revisions. Contemporary Accounting Research 34 (4): 1880–1914.

Hennes, K.M., A.J. Leone, and B.P. Miller. 2014. Determinants and market consequences of auditor dismissals after accounting restatements. The Accounting Review 89 (3): 1051–1082.

Hoag, M., M. Myring, and J. Schroeder. 2017. Has Sarbanes-Oxley standardized audit quality? American Journal of Business. 32 (1): 2–23.

Hoenig, J. M., and D. M. Heisey. (2001). The abuse of power. The pervasive fallacy of power calculations for data analysis. American statistician 55 (1): 19.24.

Hogan, C.E., and R.D. Martin. 2009. Risk shifts in the market for audits: An examination of changes in risk for “second tier” audit firms. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 28 (2): 93–118.

Hoitash, R., and U. Hoitash. 2009. The role of audit committees in managing relationships with external auditors after SOX: Evidence from the USA. Managerial Auditing Journal 24 (4): 368–397.

Hollie, D., J. Livnat, and B. Segal. 2005. Oops, our earnings were indeed preliminary. The Journal of Portfolio Management 31 (2): 94–104.

Hollie, D., J. Livnat, and B. Segal. 2012. Earnings revisions in SEC filings from prior preliminary announcements. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance 27 (1): 3–31.

Hux, C. T., and A. B. Zimmerman. (2020). Organizational climates in non-big 4 Vis-à-Vis big 4 accounting firms. Working paper, Northern Illinois University and Florida State University.

Johnson, E., I. Khurana, and K.J. Reynolds. 2002. Audit-firm tenure and the quality of financial reports. Contemporary Accounting Research 19 (4): 637–660.

Johnson, T.L., and E.C. So. 2018. Time will tell: Information in the timing of scheduled earnings news. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 53 (6): 2431–2464.

Johnson, W.B., and T. Lys. 1990. The market for audit services: Evidence from voluntary auditor changes. Journal of Accounting and Economics 12 (1–3): 281–308.

Kanodia, C., and A. Mukherji. 1994. Auditing pricing, lowballing and auditor turnover: A dynamic analysis. The Accounting Review 69 (4): 593–615.

Kinney, W.R., Jr., Z.V. Palmrose, and S. Scholz. 2004. Auditor independence, non-audit services, and restatements: Was the U.S. government right? Journal of Accounting Research 42 (3): 561–588.

Krishnan, J., and J.S. Yang. 2009. Recent trends in audit report and earnings announcement lags. Accounting Horizons 23 (3): 265–288.

Landsman, W.R., K.K. Nelson, and B.R. Rountree. 2009. Auditor switches in the pre- and post-Enron eras: Risk or realignment? The Accounting Review 84 (2): 531–558.

Lennox, C. 2000. Do companies successfully engage in opinion-shopping? Evidence from the UK. Journal of Accounting and Economics 29 (3): 321–337.

Li, E.X., and K. Ramesh. 2009. Market reaction surrounding the filing of periodic SEC reports. The Accounting Review 84 (4): 1171–1208.

Livnat, J., and L. Zhang. 2015. Is there news in the timing of earnings announcements? Journal of Investing 24 (4): 17–26.

Magee, R.P., and M.-C. Tseng. 1990. Audit pricing and independence. The Accounting Review 65 (2): 315–336.

Marshall, N.T., J.H. Schroeder, and T.L. Yohn. 2019. An incomplete audit at the earnings announcement: Implications for financial reporting quality and the market’s response to earnings. Contemporary Accounting Research 36 (4): 2035–2068.

Matsumura, E.M., K.R. Subramanyam, and R.R. Tucker. 1997. Strategic auditor behavior and going-concern decisions. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 24 (6): 727–758.

Myers, J.N., L. Myers, and T. Omer. 2003. Exploring the term of the auditor-client relationship and the quality of earnings: A case for mandatory auditor rotation? The Accounting Review 78 (3): 779–799.

Newton, N.J., D. Wang, and M.S. Wilkins. 2013. Does a lack of choice lead to lower quality? Evidence from auditor competition and client restatements. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 32 (3): 31–67.

Newton, N.J., J.S. Perselin, D. Wang, and M.S. Wilkins. 2015. Internal control opinion shopping and audit market concentration. The Accounting Review 91 (2): 603–623.

Reichelt, K.J., and D. Wang. 2010. National and office-specific measures of auditor industry expertise and effects on audit quality. Journal of Accounting Research 48 (3): 647–686.

Schroeder, J.H. 2016. The impact of audit completeness and quality on earnings announcement GAAP disclosures. The Accounting Review 91 (2): 677–705.

Schroeder, J.H., and C.E. Hogan. 2013. The impact of PCAOB AS5 and the economic recession on client portfolio characteristics of the big 4 audit firms. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 32 (4): 95–127.

Schwartz, K.B., and B.S. Soo. 1996. The association between auditor changes and reporting lags. Contemporary Accounting Research 13 (1): 353–370.

Seidel, T.A. 2017. Auditors’ response to assessments of high control risk: Further insights. Contemporary Accounting Research 34 (3): 1340–1377.

Sengupta, P. 2004. Disclosure timing: Determinants of quarterly earnings release dates. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 23 (6): 457–482.

Shipman, J.E., Q.T. Swanquist, and R.L. Whited. 2017. Propensity score matching in accounting research. The Accounting Review 92 (1): 213–244.

Shu, S.Z. 2000. Auditor resignations: Clientele effects and legal liability. Journal of Accounting and Economics 29 (2): 173–205.

Simunic, D.A., and M.T. Stein. 1990. Audit risk in a client portfolio context. Contemporary Accounting Research 6 (2): 329–343.

U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO). (2003). Public accounting firms: Mandated study on consolidation and competition. Available at: http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d03864.pdf.

U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO). (2008). Continued concentration in audit market for large public companies does not call for immediate action. Available at: http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d08163.pdf

Whisenant, J. S. (2006). An analysis of the information content of auditor change announcements: Grant Thornton LLP engagements. The Grant Thornton Commentary Series – Investor Perceptions of Audit Firm Parity 1 (1).

Whisenant, S., S. Sankaraguruswamy, and K. Raghunandan. 2003. Evidence on the joint determination of audit and non-audit fees. Journal of Accounting Research 41 (4): 721–744.

Windsor, C.A., and N.M. Ashkanasy. 1995. The effect of client management bargaining power, moral reasoning development, and belief in a just world on auditor independence. Accounting, Organizations and Society 20 (7/8): 701–720.

Yu, F. 2008. Analyst coverage and earnings management. Journal of Financial Economics 88 (2): 245–271.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 72 kb)

Appendix: Variable definitions

Appendix: Variable definitions

Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

ΔAccelerated | The change in whether the firm is an accelerated filer under SEC rules in the current year, relative to the prior year |

ΔAnalyst Following | The change in the number of analysts that follow the firm (from I/B/E/S) from the prior year |

ΔARINV | The change in the sum of accounts receivable and inventory scaled by total assets from the prior year |

ΔAudit Fees | The percentage change in audit fees relative to the prior year |

ΔBigN | The change in whether the firm is audited by a Big N audit firm in the current year relative to the prior year |

ΔBusy | The change in whether the firm’s fiscal year ends in December or January in the current compared to the prior year |

ΔEA Audit Completeness | The change in the degree of audit completeness at the EA date; EA Audit Completeness is set equal to zero when the EA is released on or after the audit report date and equals the number of days between the EA date and the audit report date when the EA is released before the audit report date |

ΔEA Lag | The difference in annual EA lag (i.e., the number of days between the client’s fiscal year end and the EA date) relative to the prior year |

ΔExpected EA Lag | The difference in expected annual EA lag (i.e., the number of days between the client’s fiscal year end and the expected EA date based on Wall Street Horizon data) relative to the prior year EA lag |

ΔGC | The change in whether the firm received a going-concern audit report modification relative to the prior year |

ΔICMW | The change in whether the firm received an adverse internal controls audit opinion (or disclosed a material weakness) in the current year compared to the prior year |

ΔLARGE ACCEL | The change in whether firm is a large accelerated filer under SEC rules in the current year, relative to the prior year |

ΔLeverage | The change in leverage compared to the prior year |

ΔLIT | The change in whether the firm is in a high litigation-risk industry relative to the prior year |

ΔLoss | The change in whether the firm reported a loss in the current year compared to the prior year |

ΔM&A | The change in whether the firm reported merger or acquisition activity in the current year compared to the prior year |

ΔMTB | The change in the market-to-book ratio from the prior year |

ΔOCF | The change in operating cash flows from the prior year |

ΔROA | The change in return on assets from the prior year |

ΔSize | The change in the natural log of total assets from the prior year |

ΔUE NEG | The change in unexpected earnings relative to the prior year |

σCASHREV | Standard deviation of cash-based revenues (revenues - ∆ accounts receivable) divided by lagged total assets computed over the period t-5 to t |

σCFO | Standard deviation of cash flows divided by lagged total assets computed over the period t-5 to t |

Industry | Industry fixed effects using SIC codes to define industries as follows (Ashbaugh et al. 2003): agriculture (0100–0999), mining and construction (1000–1999, excluding 1300–1399), food (2000–2111), textiles and printing/publishing (2200–2799), chemicals (2800–2824; 2840–2899), pharmaceuticals (2830–2836), extractive (1300–1399; 2900–2999), durable manufacturers (3000–3999, excluding 3570–3579 and 3670–3679), transportation (4000–4899), retail (5000–5999), services (7000–8999, excluding 7370–7379), computers (3570–3579; 3670–3679; 7370–7379), and utilities (4900–4999) |

Year | Year fixed effects |

2 Yr Avg % EA Delay (Audit Firm) | The average proportion of clients within an audit firm over the two previous years that experience an EA delay |

2 Yr Avg % EA Delay (Audit Firm MSA) | The average proportion of clients within an audit firm-MSA over the two previous years that experience an EA delay |

Accelerated | An indicator variable set equal to one if the firm is an accelerated filer under SEC rules, and zero otherwise |

ACCEL LARGE | An indicator variable set equal to one if the firm is a large accelerated filer under SEC rules, and zero otherwise |

Analyst Following | An indicator variable equal to one if analysts follow the firm (from I/B/E/S), and zero otherwise |

ARINV | The sum of accounts receivable and inventory scaled by total assets |

BigN | An indicator variable set equal to one if the firm is audited by one of the Big N audit firms, and zero otherwise |

BTM | The ratio of the book value of common equity to the market value of common equity |

Busy | An indicator variable set equal to one if the firm’s fiscal year ends in December or January, and zero otherwise |

CAR | Cumulative abnormal (market-adjusted) returns |

Dismiss | An indicator variable set equal to one if the auditor is dismissed in the year following the filing of the 10-K but before the filing of the subsequent year 10-K, and zero otherwise |

Dismiss Following Delay | An indicator variable set equal to one if 1 if the auditor was dismissed in the year following an EA Delay that occurred in year t-1, t-2, or t-3, and to zero otherwise |

EA Delay | An indicator variable set equal to one if there is a delay in the expected annual EA date, and zero otherwise |

EA Delay < 7 days | An indicator variable set equal to one if there is a delay of seven days or less in the expected annual EA date, and zero otherwise |

EA Delay > 7 days | An indicator variable set equal to one if there is a delay of seven or more days in the expected annual EA date, and zero otherwise |

EA Delay (Q1 through Q3) | An indicator variable set equal to one if there is a delay in the expected EA date during any of the interim quarters but not the annual EA, and zero otherwise |

EA Revision or Restate | An indicator variable set equal to one if the EA is revised prior to the filing of the annual financial statements or if the financial statements in the annual filing are subsequently restated (as revealed through a subsequent Item 4.02 non-reliance restatement), and zero otherwise |

Expected EA Lag | The number of days between the firm’s fiscal year-end and the expected EA date |

GC | An indicator variable set equal to one if the firm receives a going-concern modification in the audit report, and zero otherwise |

ICMW | An indicator variable set equal to one if the firm reports a material weakness in internal controls over financial reporting, and zero otherwise |

Issue | An indicator variable set equal to one if the firm issued debt and/or equity during the year, and zero otherwise |

Lag EA Audit Completeness | The completeness of the audit at the EA date in the previous year. Following Schroeder (2016), audit completeness at the EA date is captured as zero if the EA is released on or after the audit report date (i.e., complete audits). If the EA is released prior to the audit report date, then audit completeness equals the number of days between the EA date and the audit report date, which results in negative values. |

Length Prior EA Delay | The number of days of the EA delay in the previous year |

Leverage | Long-term debt plus the current portion of long-term debt scaled by total assets |

LIT | An indicator variable set equal to one if the firm is in a high litigation-risk industry, where high litigation-risk industries are defined as companies with SIC codes in the following industries: 2833–2836, 3570–3577, 7370–7374, 3600–3674, and 5200–5961, and zero otherwise |

Log Audit Fees | The natural log of audit fees |

Loss | An indicator variable set equal to one if net income is less than zero, and zero otherwise |

M&A | An indicator variable set equal to one if there was a merger or acquisition in the year, and zero otherwise |

MTB | The ratio of the market value of common equity to the book value of common equity |

NR Restate | An indicator variable set equal to one if an Item 4.02 non-reliance restatement is announced during the year, and zero otherwise |

OCF | Cash flows from operations scaled by total assets |

Post Dismiss | An indicator variable set equal to one capturing years with the successor auditor following an auditor dismissal, and zero otherwise |

Predecessor-to-Successor Auditor | One of nine indicator variables capturing the change from a Big N auditor to either another Big N auditor, a second tier auditor, or another auditor; the change from a second tier auditor to a Big N auditor, another second tier auditor, or another auditor; or the change from another auditor to a Big N auditor, a second tier auditor, or another auditor; and zero otherwise |

Restate Prior 2 yrs | An indicator variable set equal to one if the client announces a restatement during the current year under audit or during the previous year, and zero otherwise |

Restructure | An indicator variable set equal to one if the firm incurred restructuring charges during the year, and zero otherwise |

ROA | Return on assets measured as income before extraordinary items divided by total assets |

Second Tier | An indicator variable set equal to one if the firm is audited by one of the second tier audit firms (GT, BDO, McGladrey, Crowe Chizek), and zero otherwise |

Size | The natural log of total assets |

Special | An indicator variable equal to one if the firm reported special items, and zero otherwise |

Specialist | An indicator variable equal to one if the auditor is an industry specialist, defined following Reichelt and Wang (2010) as an auditor whose audit fee market share in the 2-digit SIC code exceeds 30% at the national level, and zero otherwise |

Tenure | The number of consecutive years to date of the auditor-client relationship |

UE NEG | An indicator variable set equal to one if income before extraordinary items for the current year is less than income before extraordinary items during the previous year, and zero otherwise |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chapman, K., Drake, M., Schroeder, J.H. et al. Earnings announcement delays and implications for the auditor-client relationship. Rev Account Stud 28, 45–90 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-021-09635-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-021-09635-3