Abstract

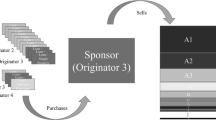

There is considerable heterogeneity in the organizational structures of CMBS loan originators that may influence originators’ underwriting incentives. We examine data on over 30,000 commercial mortgages securitized into CMBS since 1999, and find significant differences in the propensity to become delinquent depending upon whether a loan was originated by a commercial bank, investment bank, insurance company, finance company, conduit lender, or foreign-owned entity. These differences hold both before and after controlling for key loan characteristics. We then explore possible explanations for these results. Reliance on external financing during a loan’s warehousing period—the period between origination and securitization—could explain the relatively poor performance of loans originated by conduit lenders. Also, despite the potential for engaging in adverse selection, balance-sheet lenders—commercial banks, insurance companies and finance companies—actually underwrote higher-quality loans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Federal Reserve Board’s Flow of Funds Tables L.219 and L.220.

Federal Reserve Board’s Flow of Funds Tables F.219 and F.220.

The average term for loans collateralized by rent-generating commercial properties, based on the CRE portfolios of 14 large banks participating in a joint OCC-FRB data collection project, was 5.7 years with a standard deviation of 3.9. The average term in our sample of CMBS loans was 9.4 years with a standard deviation of 1.8.

In our initial sample of CMBS loans from Realpoint, 96 percent were fixed rate and 93 percent had balloon payments due at the end of the term, which averaged 120 months.

The share of loans with full or partial interest-only periods in our sample increased from 24.7 percent in 2004 to 64.3 percent in 2007. Floating-rate loans comprised a small portion of the CMBS market and we do not include them in our empirical analysis.

Investment banks have significant advantages over commercial banks in issuing complex securities due to differences in regulatory treatment and corporate culture (Kaufman 1988).

Commonly known as the CRE Finance Council Investor Reporting Package (IRP).

The B-piece investor typically has access to all the information that the mortgage originator used during the loan underwriting process (Duggins 2011).

Subordination is the only form of credit support in CMBS. Cash flows are paid out in order of seniority, only the most senior tranches receive principal payments at any given time, and the holders of the first-loss tranche exercise control over the resolution of any delinquent or defaulted loans. Control rights are typically transferred to the next lowest tranche once losses have exceeded the first-loss tranche.

The capitalization rate on a property is defined as \(\frac{NOI}{Market\;value }\), where the numerator (NOI) is the annual net operating income and the denominator is the property value assigned by the loan underwriter.

Moody’s re-underwritten loan-to-value rose from 85 percent in 2004 to 107 percent in 2007.

An et al. refer to the multiple-originator pools as “conduit” deals, as distinct from single-originator, or “portfolio,” deals. Their use of the word “conduit”in describing a deal differs from our use of the word in referring to a specific type of originator.

We interpolated rates for maturities not offered by the U.S. Treasury.

It is not possible to draw strong conclusions about how risk was priced based solely on the summary statistics on coupon spreads. While coupon spreads depend in large part on the perceived credit quality of the borrower, they also vary according to the overall loan portfolio of the borrower, time-varying risk premia, and other cost considerations.

We also consider an alternative definition that defines a loan to be delinquent at the point in time at which it enters Realpoint’s “watchlist,” a special category reserved by the rating agency for loans in danger of defaulting. The alternative definition produces a larger number of delinquencies (15.8 percent as opposed to 3.9 percent). However, the two definitions produce qualitatively similar findings, so in our results, we only report findings for the definition based on loans being 60 days late or in special servicing.

For our purposes, the incidence of delinquency refers to the share of loans that ever experience a delinquency episode, as distinct from the proportion of delinquent loans at any point in time.

As a robustness check, we estimated a binary logit specification in which the dependent variable is equal to one if a loan is ever delinquent during the sample period and equal to zero otherwise. In addition, we estimated a multinomial logit specification in which we distinguish between two types of non-delinquent loans: loans that prepay at some point in time and loans that neither become delinquent nor prepay but simply pay on time throughout the sample period. The results using both of these specifications are qualitatively similar to the hazard model (see Black et al. 2011).

In theory, we could also model the process of recovery from delinquency as well as subsequent episodes of delinquency following the initial one. However, this is not possible, as we only have data on the timing of the initial delinquency.

The vintage dummies help to control for the fact that older loans have more time to become delinquent.

By not including contemporaneous variables, our approach contrasts with that of certain other work, including Seslen and Wheaton (2010).

Treating mortgages as having a competing prepayment and default option is a long-standing approach (see Hendershott and Van Order 1987 for an early survey). However, given the similarity of the delinquency parameters in the binary and multinomial logit models (see footnote 15), we have chosen not to estimate a competing hazard model. We did estimate an alternative specification in which we treat the prepayment date as the censoring date. This specification has a somewhat different interpretation, but in practice produces very similar results.

As a robustness check, we estimated additional specifications which include dummy variables for the type of property securing the loan and the geographic region of the property. Although it is possible that the effects of geography and property type are fully captured by the core underwriting variables such as the coupon rate, DSCR, and LTV, we nonetheless included them to address the potential concern that particular types of originators may have been exogenously concentrated in certain property types or geographic regions that may have experienced distress that the originator could not have anticipated at the time of origination. The results from this robustness check are qualitatively similar to those reported in the paper, and are available from the authors upon request.

Industry sources have confirmed that commercial banks, insurance companies, investment banks, and finance companies warehoused loans internally. Foreign entities are a possible exception. Many of the foreign firms in the sample are subsidiaries of large European financial firms and may thus have access to internal sources of warehouse funding. However, it is difficult to generalize because we could not identify the parents of all of the foreign firms.

For discussions of the role of warehouse financing for CMBS conduit lenders, see pages 10 and 18 of the “Report to Congress on Risk Retention”as well as Section 1.24 of California Real Estate Finance Practice: Strategies and Forms (2011). Interesting background about the entry of investment banks into originating loans for CMBS and how investment banks fund loans prior to securitization with conduit warehouse financing is provided in O’Sullivan (1997). In addition, the Federal Reserve’s Senior Credit Officer Opinion Survey on Dealer Financing Terms (SCOOS) periodically asks specific questions about warehouse financing offered to originators of loans slated for CMBS (see, for example, the September 2010 survey). For further background, see chapter 7 of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission Final Report, which provides a detailed description of the role of warehouse financing obtained by independent mortgage originators for residential mortgages that were slated for securitization into RMBS; these firms are analogous to what we call “conduit”CMBS originators.

A report in February 1, 2008 estimated that roughly $19 billion in loans, almost all with floating rates, were trapped in the pipeline once the market ceased functioning (Commercial Mortgage Alert 2008a).

Naturally the relative power a B-piece buy has to negotiate for the exclusion of weak loans is a function of the relative strength of the market. In early 2008, as the last few CMBS deals came to market, B-piece buyers had sufficient strength to reject a sufficiently large number of loans in specific deals to force issuers to combine loans from multiple deals into new pools (Commercial Mortgage Alert 2008b).

The average time between origination and securitization in our data fell from 192 days for loans originated in 2000 to 67 days by 2007.

We note that one might consider conduit lenders to be exclusively in the CRE business. We consider them to be different in the sense that they do not hold CRE (either directly through loans or indirectly through CMBS or other holdings) on their balance sheets.

These numbers are based on data from the 2008 Flow of Funds. The bank share cited here excluded construction, land, and owner-occupied CRE loans, as they are fundamentally different from those held in CMBS and by insurance companies.

Preliminary analysis of insurance company holdings indicates that they held 55 percent of securities backed by pools containing loans originated by insurance companies, and only 49 percent of the securities backed by pools with no loans from insurance companies. Life insurance companies tended to hold senior tranches that were considered extremely unlikely to experience a principal loss. As a result, this argument may be overstated.

In particular, diversification is relatively more important at the top of the CMBS capital structure because those bonds only experience a principal loss when there are large-scale defaults. Tranches in the lower part of the CMBS capital structure typically have more varied payoff structures including interest-only, principal-only, and variable-interest notes that effectively capture any excess spread.

References

Ambrose B, Sanders AB (2003) Commercial mortgage (CMBS) default and prepayment analysis. J Real Estate Finance Econ 26(2–3):179–196

An X, Deng Y, Gabriel S (2010) Is conduit lending to blame? Asymmetric information, adverse selection, and the pricing of CMBS. Working Paper

Archer WR, Elmer PJ, Harrison DM, Ling DC (2002) Determinants of multifamily mortgage default. Real Estate Econ 30(3):445–473

Black L, Chu CS, Cohen A, Nichols JB (2011) Differences across originators in CMBS loan underwriting. Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2011-05 Federal Reserve Board of Governors, Working Paper

Ciochetti B, Deng Y, Lee G, Shilling JD, Yao R (2003) A proportional hazard model of commercial mortgage default with origination bias. J Real Estate Finance Econ 27(1):5–23

Coleman ADF, Esho N, Sharpe IG (2006) Does bank monitoring influence loan contract terms? J Financ Serv Res 30(2):177–198

Commercial Mortgage Alert (2008a) Pipeline in limbo as spreads gyrate. Commercial Mortgage Alert, 1 February 2008:3

Commercial Mortgage Alert (2008b) Credit suisse, ‘IQ’ team merge CMBS deals. Commercial Mortgage Alert, 7 March 2008:1

Cox DR (1972) Regression models and life tables. J R Stat Soc 34(2):187–220

Deng Y, Quigley JM, Sanders AB (2004) Commercial mortgage terminations: evidence from CMBS. USC Working Paper

Duggins L (2011) Investing in B-piece CMBS. Chapter five, part four of the CMBS E-Primer published by the CRE Finance Council. http://www.crefc.org/eprimer/

Esaki H, L’Heureux S, Snyderman MP (1999) Commercial mortgage defaults: an update. Real Estate Finance, Spring

Furfine C (2010) Deal complexity, loan performance, and the pricing of commercial mortgage backed securities. Kellogg School of Management Working Paper

Hendershott PH, Van Order, R (1987) Pricing mortgages: an interpretation of the models and results. J Financ Serv Res 1(1):19–55

Kaufman GG (1988) Securities activities of commercial banks: recent changes in the economic and legal environments. J Financ Serv Res 1(2):183–199

Keys BJ, Mukherjee T, Seru A, Vig V (2009) Financial regulation and securitization: evidence from subprime loans. J Monet Econ 56(5):700–720

Minton BA, Stulz R, Williamson R (2009) How much do banks use credit derivatives to hedge loans? J Financ Serv Res 35(1):1–31

Nomura Fixed Income (2005) CMBS is no exception—positive credit performance and abundance of capital lead to easing of credit protection and structural standards. Nomura Fixed Income, 15 March 2005

O’Sullivan O (1997) Cutting out the conduits. ABA Bank J 89(4):62

Puranandam A (2011) Originate- to-distribute model and the subprime mortgage crisis. Rev Financ Stud 24(6):1881–1915

Seslen T, Wheaton W (2010) Contemporaneous loan stress and termination risk in the CMBS pool. How “ruthless” is default? MIT Center of Real Estate Working Paper. Published in Real Estate Econ 38(2):225–255

Snyderman MP (1991) Commercial mortgages: default occurrence and estimated yield impact. J Portf Manage 18(1):82–87

Titman S, Tsyplakov S (2010) Originator performance, CMBS structures, and the risk of commercial mortgages. Rev Financ Stud 23(9):3558–3594

Vandell KD, Barnes W, Hartzell D, Kraft D, Wendt W (1993) Commercial mortgage defaults: proportional hazards estimation using individual loan histories. J Am Real Estate Urban Econ Assoc 21(4):451–480

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The views expressed are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve System or the Board of Governors. The authors thank participants at the Federal Reserve System Conference and the FDIC/JFSR Annual Banking Conference. Special thanks to Sarah Reynolds and Melissa Hamilton for excellent research assistance. All errors are our own.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Black, L.K., Chu, C.S., Cohen, A. et al. Differences Across Originators in CMBS Loan Underwriting. J Financ Serv Res 42, 115–134 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-011-0120-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-011-0120-0