Abstract

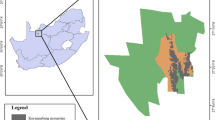

Amur Falcons Falco amurensis undergo one of the most extreme migrations of any raptor, crossing the Indian Ocean between their Asian breeding grounds and non-breeding areas in southern Africa. Adults are thought to replace all their flight feathers on the wintering grounds, but juveniles only replace some tail feathers before migrating. We compare the extent and symmetry of flight feather moult in a large sample of Amur Falcons killed at communal roosts during two hailstorms in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa in March 2019, shortly before their northward migration. Most adults had completed replacing their remiges, with only a few still growing 1–3 feathers (mainly secondaries), but most were still growing their tail feathers. Juveniles only replaced tail feathers. Moult typically was distal from the central rectrices, but 25% of adults and 1% of juveniles replaced the outer tail first, and a few individuals exhibited other moult patterns (simultaneous moult across the tail, or among the inner and outer feathers). These different moult strategies were independent of sex. Adults that replaced the outer tail first typically had replaced a greater proportion of the rectrices (mean ± SD; 0.81 ± 0.19) than adults starting from the central tail (0.17 ± 0.08). Proportionally fewer distal moulting adults were killed on 9 March than 21 March, resulting in the average proportion of rectrices replaced by adults decreasing between the two storm events from 0.52 ± 0.26 to 0.43 ± 0.23. By comparison, juvenile tail moult increased from 9 March (0.34 ± 0.18) to 21 March (0.40 ± 0.15). Overall, the probability of replacement for T1 was similar for adults (0.82) and juveniles (0.83), but adults were more likely to have replaced T2–6 (0.40–0.45) than juveniles (0.18 for T2 and 0.04–0.07 for T3–6). Asymmetry in tail moult was greater at T1 for adults (15%) than juveniles (10%), but asymmetry for T2 to T6 was greater in juveniles (3–10%) than adults (1–4%), especially given the greater probability of feather replacement in adults. Despite these differences, the degree of asymmetry was less than expected by random replacement across all rectrices in both age classes. Interestingly, moult tended to be more advanced on the left than right side of the tail. The extent of tail moult was correlated with body condition in adults and juveniles, suggesting that moult pattern might be used as an indicator of fitness in falcons.

Zusammenfassung

Ausmaß und Symmetrie der Schwanzmauser bei Amurfalken Unter allen Greifvögeln absolvieren die Amurfalken (Falco amurensis) eine der extremsten Wanderungen, auf der sie den Indischen Ozean zwischen ihren asiatischen Brutgebieten und den Nicht-Brutgebieten im südlichen Afrika überqueren. Die adulten Vögel ersetzen vermutlich im Winterquartier alle ihre Federn, wohingegen die Jungtiere vor dem Zug nur einige Schwanzfedern ersetzen. Wir vergleichen das Ausmaß und die Symmetrie der Flugfedermauser bei einer großen Stichprobe von Amurfalken, die an ihren gemeinsamen Schlafplätzen während zweier Hagelstürme in KwaZulu-Natal, Südafrika, im März 2019 kurz vor ihrem Zug nach Norden getötet wurden. Die meisten der adulten Tiere hatten den Austausch ihrer Flügelfedern abgeschlossen, nur bei einigen wenigen wuchsen noch 1–3 Federn (vor allem Handschwingen), bei den meisten aber noch die Schwanzfedern. Die Jungtiere ersetzten nur die Schwanzfedern. Die Mauser verlief typischerweise distal von den zentralen äußeren Schwanzfedern, aber 25% der adulten Tiere und 1% der Jungtiere ersetzten zuerst die äußeren Schwanzfedern, und ein paar Einzeltiere zeigten andere Mausermuster (eine gleichzeitige Mauser entweder quer über den Schwanz oder zwischen den inneren und äußeren Federn). Die unterschiedlichen Strategien in der Mauser waren unabhängig vom Geschlecht. Erwachsene Tiere, die zuerst die äußeren Schwanzfedern ersetzten, hatten in der Regel bereits den größeren Teil der Schwanzfedern ersetzt (Mittelwert ± SD; 0,81 ± 0,19), im Gegensatz zu den Adulten, deren Mauser in der Mitte des Schwanzes begann (0,17 ± 0,08). Am 9. März wurden verhältnismäßig weniger mausernde Adulte getötet als am 21. März, was dazu führte, dass bei den Adulten der durchschnittliche Anteil der ersetzten äußeren Schwanzfedern zwischen den beiden Hagelstürmen von 0,52 ± 0,26 auf 0,43 ± 0,23 abnahm. Im Vergleich dazu nahm die Schwanzmauser bei den Jungtieren vom 9. März (0,34 ± 0,18) bis zum 21. März (0,40 ± 0,15) zu. Insgesamt war die Wahrscheinlichkeit des Austauschs der T1 (T1 = Schwanzfeder 1) bei Adulten (0,82) und Jungtieren (0,83) ähnlich, aber die Adulten zeigten eine höhere Wahrscheinlichkeit, die T2-6 auszutauschen (0,40–0,45) als Jungtiere (0,18 für T2 und 0,04–0,07 für T3-6). Die Asymmetrie der Schwanzmauser war für T1 bei den Adulten größer (15%) als bei den Jungtieren (10%), aber die Asymmetrie bei T2 bis T6 war bei Jungtieren (3–10%) größer als bei Erwachsenen (1–4%), insbesondere angesichts der größeren Wahrscheinlichkeit einer kompletten Mauser bei den Adulten. Trotz dieser Unterschiede war der Grad der Asymmetrie geringer als bei einer zufälligen Mauser über alle äußeren Schwanzfedern in beiden Altersklassen zu erwarten wäre. Interessanterweise war die Mauser auf der linken Seite des Schwanzes tendenziell weiter fortgeschritten als auf der rechten. Das Ausmaß der Schwanzmauser korrelierte mit der Körperverfassung der Adulten und Jungvögeln, was darauf hindeutet, dass das Muster des Mauserverlaufs als Indikator für die Fitness von Falken verwendet werden könnte.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Alexander J, Symes CT (2016) Temporal and spatial dietary variation of Amur Falcons Falco amurensis in their South African nonbreeding range. J Raptor Res 50:276–288

Allan D (2019) Annihilation. Afr Birdl 7:22–25

Arroyo BE, King JR (1996) Age and sex differences in molt of the Montagu’s Harrier Circus pygargus. J Raptor Res 30:161–184

Arroyo B, Mínguez E, Palomares L, Pinilla J (2004) The timing and pattern of moult of flight feathers of European Storm-petrel Hydrobates pelagicus in Atlantic and Mediterranean breeding areas. Ardeola 51:365–373

Barshep Y, Mínton C, Underhill LG, Remisiewicz M (2011) The primary moult of Curlew Sandpipers Calidris ferruginea in North-western Australia shifts according to breeding success. Ardea 99:43–51

Barshep Y, Mínton C, Underhill LG, Erni B, Tomkovich P (2013) Flexibility and constraints in the molt schedule of long-distance migratory shorebirds: causes and consequences. Ecol Evol 3:1967–1976

Barta Z, Houston AI, McNamara JM, Welham RK (2006) Annual routines of non-migratory birds: Optimal moult strategies. Oikos 112:580–593

Beltran RS, Burns JM, Breed GA (2018) Convergence of biannual moulting strategies across birds and mammals. Proc Biol Sci 285:20180318

Bernitz Z (2006) Mass die-off of migrating kestrels: Ventersdorp. Gabar 17:2–4

Berthold P (1975) Migration: control and metabolic physiology. In: Farner DS, King JR (eds) Avian biology, vol 5. Academic, pp 77–128

Bojarinova JG, Lehikoinen E, Eeva T (1999) Dependence of postjuvenile moult on hatching date, condition and sex in the Great Tit. J Avian Biol 30:437–446

Brommer JE, Pihlajamäki O, Kolunen H, Pietiäinen H (2003) Life-history consequences of partial-moult asymmetry. J Anim Ecol 72:1057–1063

Brown L, Amadon D (1968) Eagles, Hawks and Falcons of the world, vol 2. Country Life Books, London, p 945

Bugoni L, Naves LC, Furness RW (2014) Moult of three Tristan da Cunha seabird species sampled at sea. Antarct Sci 27:240–251

Corso A (2001) Notes on the moult and plumages of Lesser Kestrel. Br Birds 94:409–418

Cramp S, Simmons KEL (eds) (1977) Handbook of the birds of the Western Palearctic. Oxford University Press

Dale S (2001) Female-biased dispersal, low female recruitment, unpaired males, and the extinction of small and isolated bird populations. Oikos 92:344–356

Dawson A (2006) Control of molt in birds: association with prolactin and gonadal regression in starlings. Gen Comp Endocrinol 147:314–322

Dawson A, Hinsley SA, Ferns PN, Bonser RHC, Eccleston L (2000) Rate of moult affects feather quality: A mechanism linking current reproductive effort to future survival. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 267:2093–2098

Delhey K, Guallar S, Rueda-Hernandez R, Valcu M, Wang D, Kempenaers B (2020) Partial or complete? The evolution of post-juvenile moult strategies in passerine birds. J Anim Ecol 00:1–13

Dement'ev GP, Gladkov NA eds (1951) Ptitsy Sovetskogo Soyuza (Birds of the Soviet Union, vol. 1). Gosudarstvennoe Izdatel'stvo., "Sovetskaya Nauka," Moscow. 704

Donald PF (2007) Adult sex ratios in wild bird populations. Ibis 149:671–692

Donazar JA, Feijoo JE (2002) Social structure of Andean Condor roosts: Influence of sex, age, and season. Condor 104:832–837

Ellis DH, Rohwer VG, Rohwer S (2016) Experimental evidence that a large raptor can detect and replace heavily damaged flight feathers long before their scheduled moult dates. Ibis 159:217–220

Ferguson-Lees J, Christie DA (2001) Raptors of the world. Houghton Mifflin Company

Flinks H, Helm B, Rothery P (2008) Plasticity of moult and breeding schedules in migratory European Stonechats Saxicola rubicola. Ibis 150:687–697

Fretwell SD, Calver JS (1969) On territorial behavior and other factors influencing habitat distribution in birds. Acta Biotheor 19:37–44

Ginn HB, Melville DS (1983) Moult in birds. BTO Guide 19. Bristish Trust for Ornithology, Tring, UK

Gosler AG (1991) On the use of greater covert moult and pectoral muscle as measures of condition in passerines with data for the Great Tit Parus major. Bird Study 38:1–9

Hedlund J (2019) Ecosystem in the sky - species interaction during migration over the Indian Ocean. In: The 2019 International Congress of Odonatology

Hemborg C (1999) Sexual differences in moult-breeding overlap and female reproductive costs in pied flycatchers Ficedula hypoleuca. J Anim Ecol 68:429–436

Henny CJ, Olson RA, Fleming TL (1985) Breeding chronology, molt, and measurments of Accipiter Hawks in northeastern Oregon. J Field Ornithol 56:97–112

Izhaki I, Maitav A (2008) Blackcaps Sylvia atricapilla stopping over at the desert edge; inter- and intra-sexual differences in spring and autumn migration. Ibis 140:234–243

Jenkins AR (1995) Morphometrics and flight performance of Southern African Peregrine and Lanner Falcons. J Avian Biol 26:49–58

Jenni L (1993) Structure of a Brambling Fringilla montifringilla roost according to sex, age and body-mass. Ibis 135:85–90

Jenni L, Winkler R (1996) Moult and ageing of European Passerines. Oxford University Press

Junda J, Crary AL, Pyle P (2012) An age-specific, bivariate pattern to replacement of primaries during the prebasic molt in Rufous Fantail Rhipdura rufifrons. J Ornithol 124:680–685

Kemp AC (1995) Aspects of the breeding biology and behaviour of the Secretary Bird Sagittarius serpentarius near Pretoria, South Africa. Ostrich 66:61–68

Kiat Y, Sapir N (2018) Life-history trade-offs result in evolutionary optimization of feather quality. Biol J Lin Soc 125:613–624

Kiat Y, Vortman Y, Sapir N (2019) Feather moult and bird appearance are correlated with global warming over the last 200 years. Nat Commun 10:2540

Kjellen N (1992) Differential timing of autumn migration between sex and age groups in raptors at Falsterbo, Sweden. Ornis Scand 23:420–434

Labocha MK, Hayes JP (2012) Morphometric indices of body condition in birds: A review. J Ornithol 153:1–22

Leamy LJ, Klingenberg CP (2005) The genetics and evolution of fluctuating asymmetry. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 36:1–21

Lehikoinen A, Santaharju J, Moller AP (2017) Sex-specific timing of autumn migration in birds: the role of sexual size dimorphism, migration distance and differences in breeding investment. Ornis Fennica 94:53–65

López G, Figuerola J, Varo N, Soriguer R (2005) White Wagtails Motacilla alba showing extensive post-juvenile moult are more stressed. Ardea 93:237–244

Louette M (2007) Moult patterns in the Long-tailed Hawk Urotriorchis macrourus. Ostrich 78:577–582

Meyburg BU, Howey P, Meyburg C, Pretorius R (2017) Year-round satellite tracking of Amur Falcon Falco amurensis reveals the longest migration of any raptor species across the open sea. In: Poster: From Avian Tracking to Population Processes, British Ornithologists’ Union Annual Conference, University of Warwick

Minias P, Iciek T (2013) Extent and symmetry of post-juvenile moult as predictors of future performance in Greenfinch Carduelis chloris. J Ornithol 154:465–468

Morbey YE, Guglielmo CG, Taylor PD, Maggini I, Deakin J, Mackenzie SA, Brown JM, Zhao L (2017) Evaluation of sex differences in the stopover behavior and postdeparture movements of wood-warblers. Behav Ecol 29:117–127

Morrison CA, Robinson RA, Clark JA, Gill JA (2016) Causes and consequences of spatial variation in sex ratios in a declining bird species. J Anim Ecol 85:1298–1306

Neto JM, Gosler AG (2006) Post-juvenile and post-breeding moult of Savi’s Warblers Locustella luscinioides in Portugal. Ibis 148:39–49

Newton I (2011) Migration within the annual cycle: species, sex and age differences. J Ornithol 152:169–185

Newton I, Marquiss M (1982) Moult in the Sparrowhawk. Ardea 70:163–172

Nilsson JA, Svenssonn E (1996) The cost of reproduction: a new link between current reproductive effort and future reproductive success. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 263:711–714

Payne RB (1972) Mechanisms and control of molt. In: Farner DS, King JR (eds) Avian biology, vol 2. Academic, pp 103–105

Peig J, Green AJ (2009) New perspectives for estimating body condition from mass/length data: The scaled mass index as an alternative method. Oikos 118:1883–1891

Pietersen DW, Symes CT (2010) Assessing the diet of Amur Falcon Falco amurensis and Lesser Kestrel Falco naumanni using stomach content analysis. Ostrich 81:39–44

Pietiainen H, Saurola P, Kolunen H (1984) The reproductive constraints on moult in the Ural owl Strix uralensis. Ann Zool Fenn 21:277–281

Pyle P (1995) Incomplete flight feather molt and age in certain North American non-passerines. N Am Bird Bander 20:15–26

Pyle P (2005) Remigial molt patterns in north American falconiformes as related to age, sex, breeding status, and life-history strategies. Condor 107:823–834

Pyle P (2013) Evolutionary implications of synapomorphic wing-molt sequences among falcons (Falconiformes) and parrots (Psittaciformes). Condor 115:593–602

R Core Team (2019) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing

Ramirez J, Panuccio M (2019) Flight feather moult in Western Marsh Harriers during autumn migration. Avian Research 10:1–6

Rohwer VG, Rohwer S (2013) How do birds adjust the time required to replace their flight feathers? Auk 130:699–707

Rohwer S, Rohwer VG (2018) Primary molt in Gruiforms and simpler molt summary tables. PeerJ 6:e5499

Rohwer S, Viggiano A, Marzluff JM (2011) Reciprocal tradeoffs between molt and breeding in albatrosses. Condor 113:61–70

Schafer S (2003) Study on a Mongolian breeding population of the Amur Falcon Falco amurensis. PhD Thesis, Martin Luther University, Halle-Wittenberg

Senar JC, Copete JL, Martin AJ (2008) Behavioural and morphological correlates of variation in the extent of postjuvenile moult in the Siskin Carduelis spinus. Ibis 140:661–669

Serra L, Whitelaw DA, Tree AJ, Underhill LG (1999) Moult, mass and migration of Grey Plovers Pluvialis squatarola wintering in South Africa. Ardea 87:71–81

Serra L, Griggio M, Licheri D, Pilastro A (2007) Moult speed constrains the expression of a carotenoid-based sexual ornament. Eur Soc Evol Biol 20:2028–2034

Stiles FG (1995) Intraspecific and interspecific variation in molt patterns of some tropical hummingbirds. Auk 112:118–132

Stresemann E, Stresemann V (1968) The moult of Tawny Pipit Anthus campestris and Richard’s Pipit Anthus richardi. J Ornithol 109:17–21

Studer-Thiersch A (2000) What 19 years of observation on captive Greater Flamingos suggests about adaptations to breeding under irregular conditions. Waterbirds 23:150–159

Svensson E, Nilsson JÅ (1997) The trade-off between molt and parental care: A sexual conflict in the blue tit? Behav Ecol 8:92–98

Symes CT, Woodborne S (2010) Migratory connectivity and conservation of the Amur Falcon Falco amurensis: a stable isotope perspective. Bird Conserv Int 20:134–148

Thomas ALR (1993) The aerodynamic costs of asymmetry in the wings and tail of birds: asymmetric birds can’t fly round tight corners. Philos Trans R Soc B Biological Sci 254:181–189

Thomas ALR (1997) On the Tails of Birds. Bioscience 47:215–225

Verhulst S (1998) Multiple breeding in the Great Tit, II. The costs of rearing a second clutch. Funct Ecol 12:132–140

Verhulst S, Nilsson JÅ (2008) The timing of birds’ breeding seasons: a review of experiments that manipulated timing of breeding. Philos Trans R Soc B Biological Sci 363:399–410

Weimerskirch H (1991) Sex-specific differences in molt strategy in relation to breeding in the wandering albatross. Condor 93:731–737

Wetmore S (1915) A Peculiarity in the growth of the tail feathers of the Giant Hornbill Rhinoplax vigil. Auk 32:113–114

Woolfenden BE, Gibbs HL, Sealy SG (2001) Demography of Brown-headed Cowbirds at Delta Marsh, Manitoba. Auk 118:156–166

Zanette L (2001) Indicators of habitat quality and the reproductive output of a forest songbird in small and large fragments. J Avian Biol 32:38–46

Zuberogoitia I, Gil JA, Martínez JE, Erni B, Aniz B, López-López P (2016) The flight feather moult pattern of the Bearded Vulture Gypaetus barbatus. J Ornithol 157:209–217

Zuberogoitia I, Zabala J, Martínez JE (2018) Moult in birds of prey: A review of current knowledge and future challenges for research. Ardeola 65:183–207

Acknowledgements

We thank management, staff, interns and volunteers of Durban Natural Science Museum, Durban, South Africa for help and logistics. The staff of FreeMe KwaZulu-Natal Wildlife Rehabilitation Centre, especially Wade Whitehead and Tammy Caine, as well as Ben Hoffman of Raptor Research and Meyrick Bowker are thanked for assistance in making the falcon carcasses available. OEA’s study was funded by the South African National Research Foundation (Grant no. 110950), the DST-NRF Centre of Excellence at the FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology and a UCT International/Refugee Scholarship for Postgraduate Students. We also thank Peter Pyle, Sievert Rohwer and an anonymous reviewer for helpful suggestions on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OEA: manuscript writing, statistical analysis, and data collection; DGA: manuscript revisions and data collection; BZ: manuscript revisions and data collection; WD: data collection; PGR: manuscript writing and revisions, data collection and analysis, supervision. OEA, DGA, BZ, and PGR discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Communicated by O. Krüger.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Adekola, O.E., Allan, D.G., Bernitz, Z. et al. Extent and symmetry of tail moult in Amur Falcons. J Ornithol 162, 655–667 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-021-01874-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-021-01874-0