Abstract

Background

The currently used single-monitoring method for drug–blood-level evaluation in cyclosporine A (CsA) treatment for nephrotic syndrome (NS) was established through hourly measurements based on adult organ transplantation. However, the pharmacokinetics may differ due to different concomitant medications, age, and conditions. This study was conducted to determine the measurement timing that best reflects the CsA area under the curve (AUC) in pediatric NS.

Methods

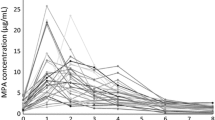

This retrospective study included children aged 2–14 years who were started on CsA treatment for idiopathic NS during 2013–2020. AUC0–4 was calculated from 7 points, before and 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, and 4 h after administration. Mean values at each timing were compared with age-dependent different drug forms. Correlation between AUC0–4 and measurement timing was analyzed.

Results

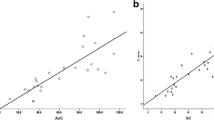

There were 13 patients (11 boys) whose median age during testing was 7.3 years, and the total number of measurements was 94. The highest timing of CsA concentrations was found in C1 59.6%. The content liquid used at younger ages had a faster absorption time to peak value and lower blood concentration than those of capsules. Among the significant correlations observed, AUC0–4 and C1.5 showed the strongest significant correlation coefficient (r = 0.93, P < 0.001).

Conclusion

In pediatric NS, CsA metabolism may be faster than that in previous organ transplantation. Compared with C2, C1.5 monitoring may result in better disease control as it can best reflect the AUC0–4 and peak values associated with side effects, which are indicators of therapeutic efficacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed in the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- CsA:

-

Cyclosporine A

- ECLIA:

-

Electro-chemiluminescence immunoassay

- EMIT:

-

Enzyme-multiplied immunoassay technique

- NS:

-

Nephrotic syndrome

- SRNS:

-

Steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome

References

Srinivas NR. Therapeutic drug monitoring of cyclosporine and area under the curve prediction using a single time point strategy: appraisal using peak concentration data. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2015;36(9):575–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdd.1967.

Oellerich M, Armstrong VW. Two-hour cyclosporine concentration determination: an appropriate tool to monitor neoral therapy? Ther Drug Monit. 2002;24(1):40–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007691-200202000-00008.

Weber LT. Therapeutic drug monitoring in pediatric renal transplantation. Pediatr Nephrol. 2015;30(2):253–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-014-2813-8.

Levy G, Thervet E, Lake J, Uchida K, Consensus on Neoral CERiTG. Patient management by Neoral C(2) monitoring: an international consensus statement. Transplantation. 2002;73(9 Suppl):S12–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007890-200205151-00003.

Kahan BD, Welsh M, Rutzky LP. Challenges in cyclosporine therapy: the role of therapeutic monitoring by area under the curve monitoring. Ther Drug Monit. 1995;17(6):621–4. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007691-199512000-00013.

Keown P, Landsberg D, Halloran P, Shoker A, Rush D, Jeffery J, et al. A randomized, prospective multicenter pharmacoepidemiologic study of cyclosporine microemulsion in stable renal graft recipients. Report of the Canadian Neoral Renal Transplantation Study Group. Transplantation. 1996;62(12):1744–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007890-199612270-00009.

David OJ, Johnston A. Limited sampling strategies for estimating cyclosporin area under the concentration-time curve: review of current algorithms. Ther Drug Monit. 2001;23(2):100–14. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007691-200104000-00003.

International Neoral Renal Transplantation Study G. Cyclosporine microemulsion (Neoral) absorption profiling and sparse-sample predictors during the first 3 months after renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2002;2(2):148–56. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.020206.x.

David-Neto E, Araujo LM, Brito ZM, Alves CF, Lemos FC, Yagyu EM, et al. Sampling strategy to calculate the cyclosporin-A area under the time-concentration curve. Am J Transplant. 2002;2(6):546–50. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.20609.x.

Barama A, Sepandj F, Gough J, McKenna R. Correlation between Neoral 2 hours post-dose levels and histologic findings on surveillance biopsies. Transplant Proc. 2004;36(2 Suppl):465S-S467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transproceed.2003.12.039.

Citterio F. Evolution of the therapeutic drug monitoring of cyclosporine. Transplant Proc. 2004;36(2 Suppl):420S-S425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.01.054.

Iijima K, Sako M, Oba MS, Ito S, Hataya H, Tanaka R, et al. Cyclosporine C2 monitoring for the treatment of frequently relapsing nephrotic syndrome in children: a multicenter randomized phase II trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(2):271–8. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.13071212.

Griveas I, Visvardis G, Papadopoulou D, Nakopolou L, Karanikas E, Gogos K, et al. Effect of cyclosporine therapy with low doses of corticosteroids on idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Artif Organs. 2010;34(3):234–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1594.2009.00838.x.

Kuroyanagi Y, Gotoh Y, Kasahara K, Nagano C, Fujita N, Yamakawa S, et al. Effectiveness and nephrotoxicity of a 2-year medium dose of cyclosporine in pediatric patients with steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome: determination of the need for follow-up kidney biopsy. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2018;22(2):413–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-017-1444-3.

Henriques Ldos S, Matos Fde M, Vaisbich MH. Pharmacokinetics of cyclosporin-a microemulsion in children with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2012;67(10):1197–202. https://doi.org/10.6061/clinics/2012(10)12.

Filler G. How should microemulsified Cyclosporine A (Neoral) therapy in patients with nephrotic syndrome be monitored? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20(6):1032–4. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfh803.

Naito M, Takei T, Eguchi A, Uchida K, Tsuchiya K, Nitta K. Monitoring of blood cyclosporine concentration in steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Intern Med. 2008;47(18):1567–72. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.47.1088.

Nozu K, Iijima K, Sakaeda T, Okumura K, Nakanishi K, Yoshikawa N, et al. Cyclosporin A absorption profiles in children with nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20(7):910–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-005-1844-6.

Kusaba T, Konno Y, Hatta S, Fujino T, Yasuda T, Miura H, et al. More stable and reliable pharmacokinetics with preprandial administration of cyclosporine compared with postprandial administration in patients with refractory nephrotic syndrome. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25(1):52–8. https://doi.org/10.1592/phco.25.1.52.55617.

Shirai S, Yasuda T, Tsuchida H, Kuboshima S, Konno Y, Shima Y, et al. Preprandial microemulsion cyclosporine administration is effective for patients with refractory nephrotic syndrome. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2009;13(2):123–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-008-0112-z.

Ushijima K, Uemura O, Yamada T. Age effect on whole blood cyclosporine concentrations following oral administration in children with nephrotic syndrome. Eur J Pediatr. 2012;171(4):663–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-011-1633-0.

Takeda A, Horike K, Onoda H, Ohtsuka Y, Yoshida A, Uchida K, et al. Benefits of cyclosporine absorption profiling in nephrotic syndrome: preprandial once-daily administration of cyclosporine microemulsion improves slow absorption and can standardize the absorption profile. Nephrology (Carlton). 2007;12(2):197–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1797.2007.00773.x.

Ahlmen J, Sundberg A, Gustavsson A, Strombom U. Decreased nephrotoxicity after the use of a microemulsion formulation of cyclosporine A compared to conventional solution. Transplant Proc. 1995;27(6):3432–3.

Halloran PF, Helms LM, Kung L, Noujaim J. The temporal profile of calcineurin inhibition by cyclosporine in vivo. Transplantation. 1999;68(9):1356–61. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007890-199911150-00023.

Melter M, Rodeck B, Kardorff R, Hoyer PF, Brodehl J. Pharmacokinetics of cyclosporine in pediatric long-term liver transplant recipients converted from Sandimmun to Neoral. Transpl Int. 1997;10(6):419–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001470050080.

Medeiros M, Perez-Urizar J, Mejia-Gaviria N, Ramirez-Lopez E, Castaneda-Hernandez G, Munoz R. Decreased cyclosporine exposure during the remission of nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22(1):84–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-006-0300-6.

Weber LT, Armstrong VW, Shipkova M, Feneberg R, Wiesel M, Mehls O, et al. Cyclosporin A absorption profiles in pediatric renal transplant recipients predict the risk of acute rejection. Ther Drug Monit. 2004;26(4):415–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007691-200408000-00012.

Ishikura K, Matsumoto S, Sako M, Tsuruga K, Nakanishi K, Kamei K, et al. Clinical practice guideline for pediatric idiopathic nephrotic syndrome 2013: medical therapy. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2015;19(1):6–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-014-1030-x.

Stein CM, Murray JJ, Wood AJ. Inhibition of stimulated interleukin-2 production in whole blood: a practical measure of cyclosporine effect. Clin Chem. 1999;45(9):1477–84.

Falck P, Vethe NT, Asberg A, Midtvedt K, Bergan S, Reubsaet JL, et al. Cinacalcet’s effect on the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus, cyclosporine and mycophenolate in renal transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(3):1048–53. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfm632.

Zotta F, Vivarelli M, Emma F. Update on the treatment of steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-021-04983-3.

Mahalati K, Belitsky P, Sketris I, West K, Panek R. Neoral monitoring by simplified sparse sampling area under the concentration-time curve: its relationship to acute rejection and cyclosporine nephrotoxicity early after kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 1999;68(1):55–62. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007890-199907150-00011.

Rinaldi S, Sesto A, Barsotti P, Faraggiana T, Sera F, Rizzoni G. Cyclosporine therapy monitored with abbreviated area under curve in nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20(1):25–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-004-1618-6.

Nashan B, Bock A, Bosmans JL, Budde K, Fijter H, Jaques B, et al. Use of neoral C monitoring: a European consensus. Transpl Int. 2005;18(7):768–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1432-2277.2005.00151.x.

Wu CY, Benet LZ. Disposition of tacrolimus in isolated perfused rat liver: influence of troleandomycin, cyclosporine, and gg918. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31(11):1292–5. https://doi.org/10.1124/dmd.31.11.1292.

Ray JE, Keogh AM, McLachlan AJ, Akhlaghi F. Cyclosporin C(2) and C(0) concentration monitoring in stable, long-term heart transplant recipients receiving metabolic inhibitors. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2003;22(7):715–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1053-2498(02)00649-6.

Yantorno SE, Varela EB, Raffa SR, Descalzi VI, Gomez Carretero ML, Pirola DA, et al. How common is delayed cyclosporine absorption following liver transplantation? Liver Transpl. 2005;11(2):167–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.20341.

Morgan ET. Regulation of cytochromes P450 during inflammation and infection. Drug Metab Rev. 1997;29(4):1129–88. https://doi.org/10.3109/03602539709002246.

Iber H, Sewer MB, Barclay TB, Mitchell SR, Li T, Morgan ET. Modulation of drug metabolism in infectious and inflammatory diseases. Drug Metab Rev. 1999;31(1):29–41. https://doi.org/10.1081/dmr-100101906.

Trompeter R, Fitzpatrick M, Hutchinson C, Johnston A. Longitudinal evaluation of the pharmacokinetics of cyclosporin microemulsion (Neoral) in pediatric renal transplant recipients and assessment of C2 level as a marker for absorption. Pediatr Transplant. 2003;7(4):282–8. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1399-3046.2003.00077.x.

Christians U, Strom T, Zhang YL, Steudel W, Schmitz V, Trump S, et al. Active drug transport of immunosuppressants: new insights for pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Ther Drug Monit. 2006;28(1):39–44. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ftd.0000183385.27394.e7.

Grant D, Kneteman N, Tchervenkov J, Roy A, Murphy G, Tan A, et al. Peak cyclosporine levels (Cmax) correlate with freedom from liver graft rejection: results of a prospective, randomized comparison of neoral and sandimmune for liver transplantation (NOF-8). Transplantation. 1999;67(8):1133–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007890-199904270-00008.

Kengne-Wafo S, Massella L, Diomedi-Camassei F, Gianviti A, Vivarelli M, Greco M, et al. Risk factors for cyclosporin A nephrotoxicity in children with steroid-dependant nephrotic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(9):1409–16. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.01520209.

del Mar Fernandez De Gatta M, Santos-Buelga D, Dominguez-Gil A, Garcia MJ. Immunosuppressive therapy for paediatric transplant patients: pharmacokinetic considerations. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2002;41(2):115–35. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-200241020-00004.

Oellerich M, Armstrong VW, Streit F, Weber L, Tonshoff B. Immunosuppressive drug monitoring of sirolimus and cyclosporine in pediatric patients. Clin Biochem. 2004;37(6):424–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2004.04.001.

Ptachcinski RJ, Venkataramanan R, Burckart GJ. Clinical pharmacokinetics of cyclosporin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1986;11(2):107–32. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-198611020-00002.

Hoyer PF. Therapeutic drug monitoring of cyclosporin A: should we use the area under the concentration-time curve and forget trough levels? Pediatr Transplant. 2000;4(1):2–5. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1399-3046.2000.00093.x.

Cooney GF, Habucky K, Hoppu K. Cyclosporin pharmacokinetics in paediatric transplant recipients. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;32(6):481–95. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-199732060-00004.

May DG, Porter J, Wilkinson GR, Branch RA. Frequency distribution of dapsone N-hydroxylase, a putative probe for P4503A4 activity, in a white population. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;55(5):492–500. https://doi.org/10.1038/clpt.1994.62.

Machado CG, Calado RT, Garcia AB, Falcao RP. Age-related changes of the multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein function in normal human peripheral blood T lymphocytes. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2003;36(12):1653–7. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0100-879x2003001200006.

Fujinaga S, Kaneko K, Muto T, Ohtomo Y, Murakami H, Yamashiro Y. Independent risk factors for chronic cyclosporine induced nephropathy in children with nephrotic syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91(8):666–70. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2005.080960.

Toole B, Gechtman C, Dreier J, Kuhn J, Gutierrez MR, Barrett A, et al. Evaluation of the new cyclosporine and tacrolimus automated electrochemiluminescence immunoassays under field conditions. Clin Lab. 2015;61(9):1303–15. https://doi.org/10.7754/clin.lab.2015.150225.

Haufroid V, Mourad M, Van Kerckhove V, Wawrzyniak J, De Meyer M, Eddour DC, et al. The effect of CYP3A5 and MDR1 (ABCB1) polymorphisms on cyclosporine and tacrolimus dose requirements and trough blood levels in stable renal transplant patients. Pharmacogenetics. 2004;14(3):147–54. https://doi.org/10.1097/00008571-200403000-00002.

Naesens M, Kuypers DR, Sarwal M. Calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(2):481–508. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.04800908.

Funding

This study received no specific grants from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. The authors TN and KT contributed equally to this work. TN mainly drafted the manuscript, data collection and performed the statistical analysis; TN, KT and ST contributed to the material preparation and data collection; KT and SO critically reviewed the manuscript; MM supervised the whole study process. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Teikyo University Ethical Review Board for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects (approval number 20-195-2). All procedures in studies involving human participants were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to participate/Consent for publication

The study plan outline was presented on the Teikyo University website, where patients and their guardians could ask questions about the study and opt out from the use of their data. Informed consent to participate and publication was obtained on the before blood sampling. The study was explained to all patients and their parents/guardians in plain language with explanatory documents, and written consent for participation in research and publication was obtained from the parents/guardians of all subjects. At the same time, it was clarified that the parents/guardians had the right to refuse participation and withdraw consent at will.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

About this article

Cite this article

Nishino, T., Takahashi, K., Tomori, S. et al. Cyclosporine A C1.5 monitoring reflects the area under the curve in children with nephrotic syndrome: a single-center experience. Clin Exp Nephrol 26, 154–161 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-021-02139-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-021-02139-z