Abstract

Objective and design

A cross-sectional single-center study was conducted to assess cytokine levels in aqueous humor (AH) and plasma of three different uveitis entities: definite ocular sarcoidosis (OS), definite OS associated with QuantiFERON®-TB Gold test positivity (Q + OS) and presumed tubercular uveitis (TBU).

Subjects

Thirty-two patients (15 OS, 5 Q + OS, 12 TBU) were included.

Methods

Quantification of selected cytokines was performed on blood and AH samples collected before starting any treatment. Statistical analysis was conducted using the Kruskal–Wallis test, the Mann–Whitney or Fisher test and the Principal Component Analysis (PCA).

Results

IL-6, IL-8 and IP-10 levels were higher in AH samples than in peripheral blood. In AH samples, BLC, IL-8 and IP-10 were significantly higher in definite OS than in presumptive TBU. There were no statistically significant differences in terms of cytokine levels between Q + OS and presumptive TBU. PCA showed a similar cytokine pattern in the latter two groups (IFNγ, IL-15, IL-2, IP-10, MIG), while the prevalent expression of BLC, IL-10 and MIP-3 α was seen in definite OS.

Conclusions

The different AH and plasma cytokine profiles observed in OS compared to Q + OS and TBU may help to differentiate OS from TBU in overlapping clinical phenotypes of granulomatous uveitis (Q + OS).

Similar content being viewed by others

References

World Health Organization (2020) Global tuberculosis report 2020.

Kee AR, et al. Anti-tubercular therapy for intraocular tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2016;61(5):628–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2016.03.001.

Alvarez S, McCabe WR. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis revisited: a review of experience at Boston City and other hospitals. Med (Baltim). 1984;63(1):25–55.

Ishihara M, Ohno S. Ocular tuberculosis. Nihon Rinsho. 1998;56(12):3157–61.

Gupta V, Gupta A, Rao NA. Intraocular tuberculosis—an update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52(6):561–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2007.08.015.

Cutrufello NJ, Karakousis PC, Fishler J, Albini TA. Intraocular tuberculosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2010;18(4):281–91. https://doi.org/10.3109/09273948.2010.489729.

Ang M, Chee SP. Controversies in ocular tuberculosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017;101(1):6–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-309531.

Cimino L, et al. Changes in patterns of uveitis at a tertiary referral center in Northern Italy: analysis of 990 consecutive cases. Int Ophthalmol. 2018;38(1):133–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10792-016-0434-x.

Agrawal R, et al. Standardization of nomenclature for ocular tuberculosis-results of collaborative ocular tuberculosis study (cots) workshop. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1080/09273948.2019.1653933.

Newman LS, Rose CS, Maier LA. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(17):1224–34. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199704243361706.

Rybicki BA, Major M, Popovich J, Maliank MJ, Lannuzzi MC. Racial differences in sarcoidosis incidence: a 5-year study in a health maintenance organization. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145(3):234–41. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009096.

Acharya NR, Browne EN, Rao N, Mochizuki M. Distinguishing features of ocular sarcoidosis in an international cohort of uveitis patients. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(1):119–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.07.006.

Rothova A, Alberts C, Glasius E, Kijlstra A, Buitenhuis HJ, Breebaart AC. Risk factors for ocular sarcoidosis. Doc Ophthalmol. 1989;72(3–4):287–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00153496.

Jabs DA, Johns CJ. Ocular involvement in chronic sarcoidosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1986;102(3):297–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9394(86)90001-2.

Herbort CP, Rao NA, Mochizuki M. International criteria for the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis: results of the first international workshop on ocular sarcoidosis (IWOS). Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009;17(3):160–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09273940902818861.

Mochizuki M, Smith JR, Takase H, Kaburaki T, Acharya NR, Rao NA. Revised criteria of international workshop on ocular sarcoidosis (IWOS) for the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2019;103(10):1418–22. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-313356.

Perez RL, Rivera-Marrero CA, Roman J. Pulmonary granulomatous inflammation: from sarcoidosis to tuberculosis. Semin Respir Infect. 2003;18(1):26–32. https://doi.org/10.1053/srin.2003.50005.

Drake WP, Newman LS. Mycobacterial antigens may be important in sarcoidosis pathogenesis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2006;12(5):359–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mcp.0000239554.01068.94.

Oswald-Richter K, Drake W. The etiologic role of infectious antigens in sarcoidosis pathogenesis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;31(04):375–9. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1262205.

Gupta D, Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, Jindal SK. Sarcoidosis and tuberculosis: the same disease with different manifestations or similar manifestations of different disorders. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2012;18(5):506–16. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCP.0b013e3283560809.

Agrawal R, et al. Tuberculosis or sarcoidosis: opposite ends of the same disease spectrum? Tuberculosis. 2016;98(January):21–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tube.2016.01.003.

Ang M, et al. Aqueous cytokine and chemokine analysis in uveitis associated with tuberculosis. Mol Vis. 2012;18:565–73.

Abu El-Asrar AM, et al. Cytokine and CXC chemokine expression patterns in aqueous humor of patients with presumed tuberculous uveitis. Cytokine. 2012;59(2):377–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2012.04.030.

Abu El-Asrar AM, et al. The cytokine interleukin-6 and the chemokines CCL20 and CXCL13 are novel biomarkers of specific endogenous uveitic entities. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(11):4606–13. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.16-19758.

Bolletta E, et al. Clinical relevance of subcentimetric lymph node biopsy in the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2020;00(00):1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/09273948.2020.1817503.

Govender P, Berman JS. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36(4):585–602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccm.2015.08.003.

Delgado BJ, Bajaj T. Ghon Complex. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022

Gupta D, Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, Jindal SK. Molecular evidence for the role of mycobacteria in sarcoidosis: a meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2007;30(3):508–16. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00002607.

Cimino L, et al. Searching for viral antibodies and genome in intraocular fluids of patients with Fuchs uveitis and non-infectious uveitis. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251(6):1607–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-013-2287-6.

Bonacini M, et al. Cytokine profiling in aqueous humor samples from patients with non-infectious uveitis associated with systemic inflammatory diseases. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.00358.

Balamurugan S, et al. Interleukins and cytokine biomarkers in uveitis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68(9):1750. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijo.IJO_564_20.

El-Asrar AMA, et al. Cytokine profiles in aqueous humor of patients with different clinical entities of endogenous uveitis. Clin Immunol. 2011;139(2):177–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2011.01.014.

Agrawal R, Iyer J, Connolly J, Iwata D, Teoh S. Cytokines and biologics in non-infectious autoimmune uveitis: bench to bedside. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014;62(1):74–81. https://doi.org/10.4103/0301-4738.126187.

Kim TW, Chung H, Yu HG. Chemokine expression of intraocular lymphocytes in patients with behçet uveitis. Ophthalmic Res. 2011;45(1):5–14. https://doi.org/10.1159/000313546.

Simsek M, et al. Aqueous humor IL-8, IL-10, and VEGF levels in Fuchs’ uveitis syndrome and Behçet’s uveitis. Int Ophthalmol. 2019;39(11):2629–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10792-019-01112-w.

Bae JH, Lee SC. Effect of intravitreal methotrexate and aqueous humor cytokine levels in refractory retinal vasculitis in Behcet disease. Retina. 2012;32(7):1395–402. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0b013e31823496a3.

Lacomba MS. Aqueous and serum interferon γ, interleukin (il) 2, il-4, and il-10 in patients with uveitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118(6):768. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.118.6.768.

Ahn JK, Yu HG, Chung H, Park YG. Intraocular cytokine environment in active Behçet uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142(3):429-434.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2006.04.016.

Curnow SJ, et al. Multiplex bead immunoassay analysis of aqueous humor reveals distinct cytokine profiles in uveitis. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(11):4251–9. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.05-0444.

El-Asrar AMA, et al. Differential CXC and CX3C chemokine expression profiles in aqueous humor of patients with specific endogenous uveitic entities. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59(6):2222–8. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.17-23225.

Takase H, et al. Cytokine profile in aqueous humor and sera of patients with infectious or noninfectious uveitis. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(4):1557–61. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.05-0836.

Abu El-Asrar AM, et al. Expression of interleukin (IL)-10 family cytokines in aqueous humour of patients with specific endogenous uveitic entities: elevated levels of IL-19 in human leucocyte antigen-B27-associated uveitis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2019;97(5):e780–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.14039.

Abu El-Asrar AM, et al. Local cytokine expression profiling in patients with specific autoimmune uveitic entities. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2020;28(3):453–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/09273948.2019.1604974.

Belkhou A, Younsi R, El Bouchti I, El Hassani S. Rituximab as a treatment alternative in sarcoidosis. Jt Bone Spine. 2008;75(4):511–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2008.01.025.

Bomprezzi R, Pati S, Chansakul C, Vollmer T. A case of neurosarcoidosis successfully treated with rituximab. Neurology. 2010;75(6):568–70. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ec7ff9.

Ramstein J, et al. IFN-γ–producing T-helper 17.1 cells are increased in sarcoidosis and are more prevalent than T-helper type 1 cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(11):1281–91. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201507-1499OC.

Facco M, et al. Sarcoidosis is a Th1/Th17 multisystem disorder. Thorax. 2011;66(2):144–50. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2010.140319.

Dienz O, Rincon M. The effects of IL-6 on CD4 T cell responses. Clin Immunol. 2009;130(1):27–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2008.08.018.

Sharp M, Donnelly SC, Moller DR. Tocilizumab in sarcoidosis patients failing steroid sparing therapies and anti-TNF agents. Respir Med X. 2019;1: 100004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrmex.2019.100004.

Saussine A, et al. Active chronic sarcoidosis is characterized by increased transitional blood B cells, increased IL-10-producing regulatory B cells and high BAFF levels. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(8): e43588. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0043588.

Lee N-S, Barber L, Akula SM, Sigounas G, Kataria YP, Arce S. Disturbed homeostasis and multiple signaling defects in the peripheral blood B-Cell compartment of patients with severe chronic sarcoidosis. Clin Vaccin Immunol. 2011;18(8):1306–16. https://doi.org/10.1128/CVI.05118-11.

Liu CH, Liu H, Ge B. Innate immunity in tuberculosis: host defense vs pathogen evasion. Cell Mol Immunol. 2017;14(12):963–75. https://doi.org/10.1038/cmi.2017.88.

Mitchell D, Rees RJ. A transmissible agent from sarcoid tissue. Lancet. 1969;294(7611):81–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(69)92392-7.

Kon OM, du Bois RM. Mycobacteria and sarcoidosis. Thorax. 1997;52:S47–51. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.52.2008.S47.

Mitchell D. Transmissible agents from human sarcoid and Crohn’s disease tissues. Lancet. 1976;308(7989):761–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(76)90599-7.

Smith-Rohrberg D, Sharma SK. Tuberculin skin test among pulmonary sarcoidosis patients with and without tuberculosis: its utility for the screening of the two conditions in tuberculosis-endemic regions. Sarcoidosis, Vasc Diffus lung Dis Off J WASOG. 2006;23(2):130–4.

Dobler CC. Biologic agents and tuberculosis. Microbiol Spectr. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.tnmi7-0026-2016.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Jacqueline M. Costa for the English language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LDS, EB, FG, and LC recruited the patients. MB and SC performed cytokine and immune cell profiling. LDS, MB, VM, FG, EB, CA, SC and LC contributed to the writing of the protocol and researched data. RA performed the statistical analysis. LDS, MB, RA, FA, SC and LC drafted the manuscript. LDS, MB, RA, FA, FG, EB, AZ, LF, CS, SC and LC interpreted the data and critically revised the manuscript. LC is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible Editor: John Di Battista.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

11_2022_1601_MOESM1_ESM.tif

Fig. Supplementary 1 FACS gating strategy. Gating strategy used to quantify lymphocytes, monocytes and neutrophils and CD4 + , CD8 + T cells, NK cells, NKT cells and B lymphocytes. (TIF 15113 KB)

11_2022_1601_MOESM2_ESM.tif

Fig. Supplementary 2 Leukocyte subsets in AH samples. A Leucocyte concentrations evaluated by manual counting with a Neubauer hemocytometer; B) Percentages of NK (CD56 + CD3neg), NKT (CD56 + CD3 +), B (CD19 + CD3neg), T (CD56negCD3 +), CD4T (CD56negCD3 + CD4 +) and CD8T (CD56negCD3 + CD8 +) cells; C) Ratio between the percentages of CD4 + and CD8 + T cells in AH samples from patients classified as OS (red dots), Q + OS (blue dots) and TBU (green dots). Horizontal lines show the median ± interquartile range (IQR). Data were analysed by Mann–Whitney test. (TIF 110 KB)

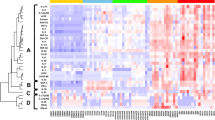

11_2022_1601_MOESM3_ESM.tif

Fig. Supplementary 3 Cytokine concentration in plasma samples. Heatmap of cytokine levels in plasma samples from each patient obtained with ClustVis software. B) Cytokine concentrations (pg/ml) detected in plasma samples from patients classified as OS (red dots), Q + OS (blue dots) and TBU (green dots). Plasma samples from control subjects (CTR) were used as reference. Horizontal lines show the median ± interquartile range (IQR). Data were analysed by Mann–Whitney test. No comparisons reached statistical significance, set ts p < 0.05. Dashed line shows the detection limit for each cytokine. (TIF 146 KB)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

De Simone, L., Bonacini, M., Aldigeri, R. et al. Could different aqueous humor and plasma cytokine profiles help differentiate between ocular sarcoidosis and ocular tuberculosis?. Inflamm. Res. 71, 949–961 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00011-022-01601-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00011-022-01601-2