Abstract

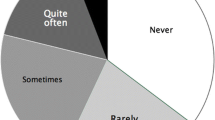

The ambivalence of human-animal-relationships culminates in our eating habits; most people disapprove of factory farming, but most animal products that are consumed come from factory farming. While psychology and sociology offer several theoretical explanations for this phenomenon our study presents an experimental approach: an attempt to challenge people’s attitude by confronting them with the animals’ perspective of the consumption process. We confronted our participants with a fictional scenario that could result in them being turned into an animal. In the scenario, a wicked fairy forces them to choose a ticket. Depending on their choice of ticket they have equal chances of becoming a human being with a certain consumption behaviour (meat eater, organic eater, vegetarian, vegan) or, correspondingly, becoming a certain kind of animal (factory farmed meat animal, organically farmed meat animal, animal for dairy/egg production, free living animal). Our results indicate a strong discrepancy between people’s actual consumption habits (mostly regular meat eaters) and their choices in the experiment (strong preferences for the organic or vegan life style). The data reveal a broad spectrum of explanations for people’s decisions in the experiment. We investigated the influence of four different factors on the participant’s choices in addition to reasons they gave as open-ended answers. Correspondingly, different coping strategies to overcome the tension (cognitive dissonance) between real-life consumption choices and attitudes towards nonhuman animals could be detected. Furthermore, many participants indicated a lack of knowledge concerning living conditions in farming but also concerning capacities and properties of nonhuman animals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The payment was recommended by the clickworker guidelines: http://www.clickworker.com/pdf/de_survey.pdf, access: 11.03.2016

There is a well-known German song by the Comedian Harmonists called “Ich wollt’ ich wär ein Huhn” (I wish I was a hen) from which our participant quotes the line “Ich legte täglich nur ein Ei und sonntags auch mal zwei.” (I would just lay one egg a day and on Sundays, sometimes, two). In the ludicrous song, the first-person narrator describes his whish to live the simple but happy life as a hen having nothing to do and nothing to worry about.

Whether the calculation is that simple or could be modified by additional factors could be tested in a separate thought experiment. What if e.g. the animals’ species was known? The image used in this thought experiment suggests a mouse which is an animal of prey. Many participants thought about a dangerous life in fear. If the image had been e.g. a fox, a snail or a sprout the participants’ associations might have been different.

It is highly unlikely that those participants quoted above all thought of lobsters, oysters and snails when thinking about their „meat consumption“. Our focus on the groups of animals that are most commonly “used” in farming was supported by the images of pigs and chicken that illustrated the thought experiment, see attachment.

References

Berndsen, Mariëtte, and Joop van der Pligt. 2004. Ambivalence towards meat. Appetite 42 (1): 71–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0195-6663(03)00119-3.

Berndsen, Mariëtte, and Joop van der Pligt. 2005. Risks of meat: The relative impact of cognitive, affective and moral concerns. Appetite 44 (2): 195–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2004.10.003.

Bratanova, Boyka, Steve Loughnan, and Brock Bastian. 2011. The effect of categorization as food on the perceived moral standing of animals. Appetite 57 (1): 193–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2011.04.020.

Cochrane, Alasdair. 2009. Do animals have an interest in liberty? Political Studies 57 (3): 660–679.

Festinger, Leon. 1962. A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford university press.

Gentle, Michael J. 1992. Pain in birds. Animal Welfare 1 (4): 235–247.

Gettier, Edmund L. 1963. Is justified true belief knowledge? analysis 23 (6): 121–123.

Gutjahr, Julia. 2013. The reintegration of animals and slaughter into discourses of meat eating. In The ethics of consumption, 379–385. Springer.

Hayley, Alexa, Lucy Zinkiewicz, and Kate Hardiman. 2015. Values, attitudes, and frequency of meat consumption. Predicting meat-reduced diet in Australians. Marketing to Children - Implications for Eating Behaviour and Obesity: A special issue with the UK Association for the Study of Obesity (ASO) 84: 98–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.10.002.

Joy, M. 2003. Psychic numbing and meat consumption: The psychology of Carnism.

Knobe, Joshua, and Shaun Nichols (eds.). 2007. Experimental philosophy: Oxford University Press.

Leahy E, Lyons S, and Tol Richard S. J. 2010. An estimate of the number of vegetarians in the world. ESRI working paper no. 340. The Economic and Social Research Institute, Dublin.

Loughnan, Steve, Nick Haslam, and Brock Bastian. 2010. The role of meat consumption in the denial of moral status and mind to meat animals. Appetite 55 (1): 156–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2010.05.043.

MacDiarmid, Jennie I., Flora Douglas, and Jonina Campbell. 2016. Eating like there’s no tomorrow: Public awareness of the environmental impact of food and reluctance to eat less meat as part of a sustainable diet. Appetite 96: 487–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.10.011.

Nagel, Thomas. 1974. What is it like to be a bat? The philosophical review 83 (4): 435–450.

Piazza, Jared, Matthew B. Ruby, Steve Loughnan, Mischel Luong, Juliana Kulik, Hanne M. Watkins, and Mirra Seigerman. 2015. Rationalizing meat consumption. The 4Ns. Appetite 91: 114–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.04.011.

Rothgerber, Hank. 2014a. A comparison of attitudes toward meat and animals among strict and semi-vegetarians. Appetite 72: 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2013.10.002.

Rothgerber, Hank. 2014b. Efforts to overcome vegetarian-induced dissonance among meat eaters. Appetite 79: 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.04.003.

Segner, Helmut. 2012. Fish: Nociception and Pain: a Biological Perspective: Federal Office for Buildings and Logistics (FOBL).

Thomson, Judith Jarvis. 1985. The trolley problem. The Yale Law Journal 94 (6): 1395–1415.

Veilleux, Sophie. 2014. Coping with dissonance: Psychological mechanisms that enable ambivalent attitudes toward animals. Honors Thesis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

German version of the scenario:

„Während eines Waldspaziergangs treffen Sie auf eine fiese Fee, die Ihnen ein Angebot macht. In ihrem Feenhut befinden sich Tickets mit vier verschiedenen Buchstaben (A, B, C, D). Sie müssen sich für ein Ticket entscheiden, es öffnen und die Aufschrift lesen. Daraufhin werden Sie sich sofort in das Wesen verwandeln, das auf dem Ticket beschrieben ist. Von nun an werden Sie als dieses Wesen weiterleben. Die Fee erklärt ihnen die unterschiedlichen Tickets (A, B, C, D):

Auf der Hälfte der A-Tickets steht “Fleisch essender Mensch” und auf der anderen Hälfte “Tier in konventioneller Tierhaltung”.

Auf der Hälfte der B-Tickets steht “vegetarisch lebender Mensch” und auf der anderen Hälfte “Tier, das zur Milch- oder Eiproduktion gehalten wird”.

Auf der Hälfte der C-Tickets steht “Mensch, der nur ökologisch erzeugte Tierprodukte isst” und auf der anderen Hälfte “Tier in ökologischer Tierhaltung”.

Auf der Hälfte der D-Tickets steht “vegan lebender Mensch” und auf der anderen Hälfte “frei lebendes Tier”.

Wenn Sie sich entscheiden, gar kein Ticket zu ziehen, wird die fiese Fee Sie augenblicklich in ein Tier verwandeln und zwar.

- in ein Tier in Massentierhaltung, wenn Sie zur Zeit ein Fleisch essender Mensch sind.

- in ein Tier, das zur Milch- und Eiproduktion gehalten wird, wenn Sie Vegetarier*in sind.

- in ein Tier in ökologischer Haltung, wenn Sie zur Zeit nur ökologisch erzeugte Tierprodukte konsumieren.

- in ein frei lebendes Tier, wenn Sie Veganer*in sind.

Würden Sie ein Ticket ziehen? Und wenn ja, welches?

Warum haben Sie sich für dieses Ticket entschieden?

Welche der folgenden Faktoren waren ausschlaggebend für Ihre Entscheidung (keine Nennung oder Mehrfachnennungen möglich)?

die Perspektive, als Tier zu leben

Ich habe auf den bestmöglichen Ausgang für mich geschaut.

Ich habe darüber nachgedacht, dass ich bereit sein muss, als Tier eines bestimmten Typs zu leben, wenn ich entsprechende Tierprodukte konsumiere..

meine derzeitigen Essgewohnheiten

die Art, wie ich in Zukunft als Mensch leben möchte.

Ich habe auf den schlechtestmöglichen Ausgang für mich geschaut.

Ich habe über Fairness nachgedacht.”

Illustrations:

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Persson, K., Appel, R. & Shaw, D. A Wicked Fairy in the Woods - how would People alter their Animal Product Consumption if they were affected by the Consequences of their Choices?. Food ethics 4, 1–20 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41055-019-00042-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41055-019-00042-8