Abstract

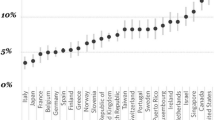

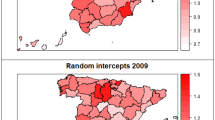

The recent economic crisis has thrown many European economies into a period of slow growth and high unemployment. While previous research looked at the impact of the crisis on aggregate indicators of entrepreneurship, not much is known about whether and how it affected individual motivations and efforts to become self-employed. This study aims to fill this gap by looking at the impact of the crisis on latent and early entrepreneurship, as well as on the link between the two. We combine individual and country-level data from 25 EU member states from 2006 to 2012. Results of multilevel logistic regressions show that the decrease in entrepreneurial activity in the post-crisis period has been stronger in countries where access to finance for SMEs has been more difficult. Moreover, we show that the high level unemployment generated by the economic crisis has produced a “refugee effect” by pushing into entrepreneurship only those individuals who are not interested in such a career choice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Those concerned with conceptual purity may note that this specification puts together nascent and young entrepreneurship, two stages that are conceptually not identical. We believe that this is the most appropriate way to proceed for several reasons. First, we find that looking at nascent entrepreneurship alone would be less substantively interesting, as nascent entrepreneurs can abandon their efforts even before their business is born. As one of the goals of this study is to capture the short-term implications of the crisis for the rise of new entrepreneurs, we find that this is better reflected by looking both at those taking the first steps to start a business, and at those who are in a slightly more advanced stage. Similarly, we do not just look at people who are “self-employed” as current working status, as many of them could be running their business for years, hence the short-term nature of the construct would be lost. Finally, we find the wording “taking steps to start a new business”, used in many surveys to observe nascent entrepreneurship, to be rather ambiguous and prone to be interpreted in different ways by different respondents, some more and some less involved in actual entrepreneurial activities, with the potential consequence to produce unreliable results.

Two specifications need to be made. First, while we focus on two different stages of the entrepreneurial process, we do not model the process itself. Our perspective is genuinely cross-sectional, as the goal is to take a snapshot at latent and early entrepreneurship, as well as their correlation, in specific places and points in time. Second, we remain agnostic about the causal direction between latent and early entrepreneurship. While it is plausible to expect latent entrepreneurship to be causally prior to early entrepreneurship, people may also be forced into self-employment by external reasons and later develop a positive attitude towards it in order to maintain consistency. While cognitive dissonance is not likely to be a strong factor in this case (as the relatively large amount of paid employees who wish to be self-employed suggests), our data do not allow us to identify clear causal paths.

The first wave of the data was collected in January 2007 (hence we assume that the data refer to 2006), the second between December 2009 and January 2010, and the third between June and August 2012. Regarding the country selection, we focus on EU25: Bulgaria and Romania have been excluded from the analyses in order to have a consistent sample between pre and post-crisis period, as the two countries joined the EU in 2007 and were not part of the Eurobarometer survey prior to that year. This is a cautious strategy to avoid the suspicion that observing those two countries only in the post-crisis period may bias the results. Note, however, that replicating the analyses using all 27 member states (with Bulgaria and Romania missing in 2006) produces nearly identical results. In total the data include 75 country/year units. Survey samples range from a minimum of 500 respondents to a maximum of 1029. The median number of respondents per survey is 511 in 2006, 520 in 2009, and 1001 in 2012. For further details, see European Commission (2008, 2011, 2013).

Since both variables are dichotomous, we used polychoric correlations instead of the more common Pearson product-moment correlations. Polychoric correlations assume a linear latent trait that is observed with ordinal items. Values are interpreted in the same way as linear correlation coefficients.

We exclude these two variables from the models for early entrepreneurship because being a student or being unemployed excludes a priori that a person is an early entrepreneur. Moreover, we exclude students from the sample in the models for early entrepreneurship, but we keep unemployed people. We do so because the exclusion from the labor market of these two groups are likely to be generated by two different processes, the former exogenous (e.g. still going to school) while the latter endogenous to the market itself (i.e. not finding a job and/or not setting up an own business). In other words, the zero-outcomes observed on students can be regarded as structural, while the zero-outcomes observed on unemployed people can be regarded as random–and thus, potentially affected by the predictors in the model.

Two important remarks regarding the indicator are necessary. First, the time series provided for the index starts in 2007, i.e. slightly after the EB data were collected. We believe that this is not a problem for the purposes of our analysis since, first, our data were too collected in January 2007, and second, there is no reason to expect such a great change within 1 year in the pre-crisis period. Moreover, in the original data the values of the index are normalized with respect to the EU average in 2007, which takes value 100.

All models have been estimated with Restricted Maximum Likelihood, using the package lme4 version 1.1-12 for R version 3.3.2. To simplify the comparability of the effects of the different variables, all the continuous indicators in the model have been centered around the grand mean and standardized, so the coefficients indicate the change in the linear predictor associated to a shift of one standard deviation away from the mean.

References

Acs, Z. (2006). How is entrepreneurship good for economic growth?. Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization, 1(1), 97–107.

Agarwal, R., Audretsch, D., & Sarkar, M. B. (2007). The process of creative construction: knowledge spillovers, entrepreneurship, and economic growth. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 1(3-4), 263–286.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (2005) In Albarracín, D., Johnson, B. T., & Zanna, M. P. (Eds.), The influence of attitudes on behavior, (pp. 173–221). Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Arenius, P., & Minniti, M. (2005). Perceptual variables and nascent entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 233–247.

Audretsch, D. B., & Acs, Z. J. (1994). New-firm startups, technology, and macroeconomic fluctuations. Small Business Economics, 6(6), 439–449.

Baliamoune-Lutz, M. (2015). Taxes and entrepreneurship in OECD countries. Contemporary Economic Policy, 33(2), 369–380.

Baron, R. A. (2014). Entrepreneurship: a process perspective. In Baum, J. R., Frese, M., & Baron, R. A. (Eds.) The Psychology of Entrepreneurship.Psychology Press.

Bassetto, M., Cagetti, M., & De Nardi, M. (2015). Credit crunches and credit allocation in a model of entrepreneurship. Review of Economic Dynamics, 18 (1), 53–76.

Baumol, W. J., & Strom, R. J. (2007). Entrepreneurship and economic growth. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 1(3-4), 233–237.

Black, S. E., & Strahan, P. E. (2002). Entrepreneurship and bank credit availability. The Journal of Finance, 57(6), 2807–2833.

Blanchflower, D. G. (2000). Self-employment in OECD countries. Labour Economics, 7, 471–505.

Blanchflower, D. G., Oswald, A., & Stutzer, A. (2001). Latent entrepreneurship across nations. European Economic Review, 45(4), 680–691.

Brixy, U., Sternberg, R., & Stüber, H. (2012). The selectiveness of the entrepreneurial process. Journal of Small Business Management, 50(1), 105–131.

Carbo-Valverde, S., Rodriguez-Fernandez, F., & Udell, G. F. (2016). Trade credit, the financial crisis, and SME access to finance. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 48(1), 113–143.

Carmo Farinha, L. M., Fereira, J. J., Lawton Smith, H., & Bagchi-Sen, S. (2015). Handbook of Research on Global Competitive Advantage through Innovation and Entrepreneurship, IGI Global.

Constant, A. F., & Zimmermann, K. F. (2004). Self-employment dynamics across the business cycle: migrants versus natives. IZA Discussion paper series.

Davidsson, P. (2006). Nascent entrepreneurship: empirical studies and developments. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 2(1), 1–76.

Deli, F. (2011). Opportunity and necessity entrepreneurship: local unemployment and the small firm effect. Journal of Management Policy and Practice, 12(4), 38–57.

DG Taxation and Customs Union (2016). Taxation trends in the European Union, Technical report, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. http://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/business/economic-analysis-taxation/data-taxation_en.

ECB (2012). Euro area labour markets and the crisis. Occasional Paper Series (138).

European Commission (2008). Flash Eurobarometer 192 (Entrepeneurship). doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.4232/1.4726.

European Commission (2011). Flash Eurobarometer 283 (Entrepreneurship in the EU and Beyond). doi:10.4232/1.10210.

European Commission (2012). SME Access to Finance Index (SMAF). http://lexicon-software.co.uk/enterprise/policies/finance/data/enterprise-finance-index/sme-access-to-finance-index/index_en.htm.

European Commission (2013). Flash Eurobarometer 354 (Entrepreneurship in the EU and Beyond). doi:10.4232/1.11590.

Faggio, G., & Silva, O. (2014). Self-employment and entrepreneurship in urban and rural labour markets. Journal of Urban Economics, 84, 67–85.

Fairlie, R. W. (2013). Entrepreneurship, economic conditions, and the great recession. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 22(2), 207–231.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

Gilad, B., & Levine, P. (1986). A behavioral model of entrepreneurial supply. Journal of Small Business Management, 24, 45.

Gohmann, S. F. (2012). Institutions, latent entrepreneurship, and self-employment: an international comparison. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(2), 295–321.

Grilo, I., & Irigoyen, J.-M. (2006). Entrepreneurship in the EU: to wish and not to be. Small Business Economics, 26(4), 305–318.

Grilo, I., & Thurik, R. (2005). Latent and actual entrepreneurship in Europe and the US: some recent developments. The International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 1(4), 441–459.

IMF (2015). World economic outlook database. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2015/01/weodata/index.aspx.

Jiménez, A., Palmero-Cámara, C., González-Santos, M. J., González-Bernal, J., & Jiménez-Eguizábal, J. A. (2015). The impact of educational levels on formal and informal entrepreneurship. Business Research Quarterly, 18, 204–212.

Klapper, L., & Love, I. (2011). The impact of the financial crisis on new firm registration. Economics Letters, 113(1), 1–4.

Klapper, L., Love, I., & Randall, D. (2015). New firm registration and the business cycle. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(2), 287–306.

Koellinger, P. D., & Thurik, A. R. (2011). Entrepreneurship and the business cycle. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 94(4), 1143–1156.

Leibenstein, H. (1968). Entrepreneurship and development. The American Economic Review, 58(2), 72–83.

Lévesque, M., & Minniti, M. (2006). The effect of aging on entrepreneurial behavior. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(2), 177–194.

Lindquist, M. J., Sol, J., & Van Praag, M. (2015). Why do entrepreneurial parents have entrepreneurial children. Journal of Labor Economics, 33(2), 269–296.

Matsusaka, J. G., & Sbordone, A. M. (1995). Consumer confidence and economic fluctuations. Economic Inquiry, 33(2), 296–318.

Minniti, M., & Naudé, W. (2010). What do we know about the patterns and determinants of female entrepreneurship across countries?. European Journal of Development Research, 22(3), 277–293.

OECD (2009). The impact of the global crisis on SME and entrepreneurship financing and policy responses.

Paniagua, J., & Sapena, J. (2015). The effect of systemic banking crises on entrepreneurship. In Peris-Ortiz, M., & Sahut, J.-M. (Eds.) New Challenges in Entrepreneurship and Finance, (pp. 195–207). Springer.

Payne, J.E. (2015). The US entrepreneurship-unemployment nexus. In Cebula, R.J., Hall, C., Mixon, F.G.J., & Payne, J.E. (Eds.), Economic Behavior, Economic Freedom, and Entrepreneurship (pp. 260–271): Edward Elgar Publishing.

Peris-Ortiz, M., Fuster-Estruch, V., & Devece-Carañana, C. (2014). Entrepreneurship and Innovation in a Context of Crisis. In Rüdiger, K., Ortiz, M. P., & González, A. B. (Eds.) Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Economic Crisis (pp. 1–10). Springer International Publishing.

Reynolds, P., & White, S. B. (1997). The Entrepreneurial Process: Economic Growth, Men, Women, and Minorities. Praeger: Conn.

Reynolds, P., Bosma, N., Autio, E., Hunt, S., Bono, N. D., Servais, I., Lopez-Garcia, P., & Chin, N. (2005). Global entrepreneurship monitor: data collection design and implementation 1998–2003. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 205–231.

Sannajust, A. (2014). Impact of the world financial crisis to SMEs: the determinants of bank loan rejection in Europe and USA, Working Paper 2014-327, Department of Research, Ipag Business School. http://econpapers.repec.org/paper/ipgwpaper/2014-327.htm.

Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. The Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 217–226.

Starr, M. A. (2012). Consumption, sentiment, and economic news. Economic Inquiry, 50(4), 1097–1111.

van der Zwan, P., Thurik, R., Verheul, I., & Hessels, J. (2016). Factors influencing the entrepreneurial engagement of opportunity and necessity entrepreneurs. Eurasian Business Review, 6(3), 273–295.

van Stel, A., Storey, D. J., & Thurik, A. R. (2007). The effect of business regulations on nascent and young business entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 28(2-3), 171–186.

Wagner, J. (2006). The life cycle Of entrepreneurial ventures In Parker, S. (Ed.), Nascent Entrepreneurs. New York: Springer.

Wennekers, S., & Thurik, R. (1999). Linking entrepreneurship and economic growth. Small Business Economics, 13(1), 27–56.

Wennekers, S., van Stel, A., Thurik, R., & Reynolds, P. (2005). Nascent entrepreneurship and the level of economic development. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 293–309.

Wood, B. D., Owens, C. T., & Durham, B. M. (2005). Presidential rhetoric and the economy. Journal of Politics, 67(3), 627–645.

World Bank (2013). World development indicators |Data. http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The work of Federico Vegetti was financially supported by the “CUPESSE” project, European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement 613257.

The work of Dragoş Adăscăliţei was financially supported by the “Cohesify” project (www.cohesify.eu), which received funding from European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement 693427.

Appendices

Appendix A: Variables Description

SMAF Index

According to the description by European Commission (2012) the SMAF index is composed by two sub-indexes, one called “Debt finance sub-index” and the other “Equity finance sub-index”. In total, the two components of the index capture 14 indicators, divided as follows:

-

1.

Debt finance sub-index

-

% of firms using bank loans

-

Interest rates on loans up to 250,000 €

-

Interest rates for overdrafts

-

% of firms using bank overdraft, credit line or credit card overdrafts

-

% of firms using leasing or hire purchase or factoring

-

% of companies not applying for bank loans because of possible rejection

-

% of firms “applied but did not get everything requested”

-

Rejected loan applications and unacceptable loan offers

-

Willingness of banks to provide a loan (% of respondents who indicated a deterioration)

-

-

2.

Equity finance sub-index

-

Total venture capital investment in thousands of €(% of GDP)

-

Number of venture capital beneficiary SMEs (scaled by GDP)

-

Total volumes invested by business angels in thousands of €(% of GDP)

-

Number of deals where business angels invested (% of GDP)

-

% of firms feeling confident to talk about financing with equity investors or venture capital firms

-

The sources reported are European Central Bank (ECB) for debt; European Venture Capital Association (EVCA) and European Business Angel Network (EBAN) for equity; EC and ECB’s Survey on the Access to Finance of SMEs (SAFE).

Question Wording Eurobarometer

We report here the question wordings of the variables utilized here coming from the 2012 Eurobarometer questionnaire on entrepreneurship. The goal of this section is to provide an example of how the individual-level constructs of interest were measured. For more details, see European commission (2008, 2011, 2013).

Preference for self-employment (Latent entrepreneurship)

- Q1: :

-

If you could choose between different kinds of jobs, would you prefer to be...

-

1)

An employee

-

2)

Self-employed

-

3)

None (DO NOT READ OUT)

-

4)

DK (DO NOT READ OUT)

-

1)

Starting a business (Early entrepreneurship)

- Q13: :

-

Have you ever started a business, taken over one or are you taking steps to start one?

-

1)

Yes, you started/took over a business

-

2)

Yes, you are taking steps to start/take over a business

-

3)

No

-

4)

DK (DO NOT READ OUT)

-

1)

- Q14b: :

-

How would you describe your situation?

-

1)

You are currently taking steps to start a new business

-

2)

You have started or taken over a business in the last three years which is still operating today

-

3)

You started or took over a business more than three years ago and it?s still operating

-

4)

You once started a business, but currently you are no longer an entrepreneur since that business has failed

-

5)

You once started a business, but currently you are no longer an entrepreneur since that business was sold, transferred or closed

-

6)

DK (DO NOT READ OUT)

-

1)

Controls

- D2: :

-

Gender (“Gender (Female)”)

-

1)

Male

-

2)

Female

-

1)

- D1: :

-

How old are you? (“Age”)

- D4: :

-

How old were you when you stopped full-time education? (“Education”)

- D5a: :

-

As far as your current occupation is concerned, would you say you are self-employed, an employee, a manual worker or would you say that you are without a professional activity? (“Unemployed”)

-

1)

Self-employed

-

2)

Employee

-

3)

Manual worker

-

4)

Without a professional activity

-

5)

Refusal (DO NOT READ OUT)

-

1)

- D7: :

-

Could you tell me the occupations of your parents? Are or were they self-employed, white- collar employees in the private sector, blue-collar employees in the private sector, civil servants or not in paid employment? (“Parents Self-Employed” – asked for both mother and father)

-

1)

Self employed

-

2)

White collar employee in the private sector

-

3)

Blue collar employee in the private sector

-

4)

Civil servants

-

5)

Not in paid employment

-

6)

Other

-

7)

DK (DO NOT READ OUT)

-

1)

Appendix B: Descriptive Statistics

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vegetti, F., Adăscăliţei, D. The impact of the economic crisis on latent and early entrepreneurship in Europe. Int Entrep Manag J 13, 1289–1314 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-017-0456-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-017-0456-5