Abstract

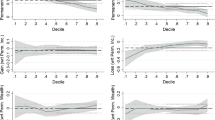

Since cell phones were introduced commercially in 1983, virtually all consumers have adopted cell phones. In this paper, we examine the effect of this new product on telephony demand and its evolution in the market using the Consumer Expenditure Survey from 1994 to 2012. This represents a period much longer than previous studies and over which most cell phone adoptions took place. We develop and estimate a model of household choice of telephony options using a mixed logit as a function of consumer characteristics, unobserved alternative-specific attributes, and prices over time. Unlike previous research, our focus is on the evolution of demand and choices made by households. To illustrate the evolution, we construct market segments and track adoptions over time by market segment, allowing for an assessment of whether cell phones are substitutes or complements for landlines. The evidence suggests that the move to cellular telephone services is driven by young households and by households with larger families. We then develop and apply a decomposition of substitutability and find significant evidence that substitutability differs through time and by market segment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Further discussion of this regulatory change through the 1980s can be found in Crandall (1988).

We considered other options for a price measure; however, the alternatives would not allow the entirety of the 19-year sample-period to be used. We did, however, compare our measures of price with other measures during overlapping time-periods, and found that our prices trend in the same direction and are highly correlated with other measures we found.

In addition to the included specifications, we estimated a binary logit for landline using cell phone price as a right-hand-side variable and found that these two services appear to be complementary. Of course, this and previous literature, e.g. Rodini et al. (2003), further motivate our specifications that consider the evolution of the industry.

Our results are consistent with Macher et al. (2013) in how non-price household characteristics matter.

The car phone was not a cellular device; instead it was a combination of radio and telephone.

The Motorola DynaTAC 8000X and Ameritech Mobile Communications (Ameritech), respectively.

2G cell phones used digital waves, and allowed for greater sharing of frequencies.

The first text message was sent in 1992 (HistoryOfCellPhones.net. 2008).

This included seamless global roaming with at least 40 times higher signal transmission rates than 2G systems.

Miravete (2002) shows that welfare effects are unchanged under different rate implementations in the demand for local telephone service in the presence of asymmetric information. Economides et al. (2008) find that firms entering the landline market have positive welfare effects through differentiation rather than through price. In Bajari et al. (2008), the authors find that “coverage is strongly valued by consumers, providing an efficiency justification for across-market mergers” in the cell phone service industry.

In addition to estimating the three specifications with the full dataset, we estimated them year-by-year. Most of the coefficients are quite stable through time except the alternative-specific dummy variables, which have considerable drift with time. For this reason, we include the year trend variable.

Multiple price variables are constructed from the expenditure data as discussed in “Constructed price variables” section of Appendix. Our results are robust to the price construction used; estimates presented here use the algorithmic approach discussed in Appendix.

The IIA assumption imposes that, when one option is taken away, there will be proportionate substitution to the other alternatives, e.g., if the no phone option is removed, IIA holds that the proportion of those individuals who did choose no-phone but now choose both among those who initially chose no-phone is equal to the proportion of individuals choosing both among those initially not choosing no-phone. In this context, we have a classic red bus/blue bus problem (Train 2009). Those initially choosing no-phone would be unlikely to choose both, but would instead be more likely to choose either cell phone or landline in greater proportion than those who did not originally choose no-phone.

The stratification of the CES is intended to create representative estimates about consumer spending at the country-level. For a more detailed explanation of the stratification procedure, see BLS (2008).

The expenditure information recorded is asked to households in terms of services included in the bill and is itemized, which allows for individual items on the same bill to be recorded separately. This abates problems with inappropriately recorded category expenditures that might otherwise be caused by bundled service offerings.

The unit of observation is a CU-quarter, although it is possible for a CU to skip an interview quarter. In addition to estimating the models with all of the observations, we estimated each using only the first observation of each household. Doing so, we get qualitatively identical and numerically similar results.

Note that for these and all estimation herein, weights are applied to observations to account for the stratification of the sample.

We note that, through time, there are modest changes in the format of the questions asked in the survey. In our particular case, there were no significant changes to the definitions for the variables used.

For the years 2004 and 2005, our measure of income (FINCBTAX) was not available in the CES. We used an alternative for those years (FINCBTXM) as, for years when both were available, these were highly correlated. In both cases, the nominal income variable is defined as total before-tax income over the previous 12 months for the CU including but not limited to salaries, unemployment benefits, business profits and losses, and retirement.

For the years for which the data overlap, the correlation coefficient for our constructed price proxies and the Consumer Price Index categories of landline telephone services and wireless telephone services are 0.8681 and 0.7746, respectively. This supports the constructed prices as effective proxies for price in the choice models. Further, we have estimated our models for the years possible using CPI rather than our price proxies and get similar results.

During the time spanned by the data, cell phones and the features available have changed dramatically creating a heterogeneous product category through time. In addition to the specifications presented here, we also estimated specifications that include indicators identifying regulatory changes and cell phone features available in the marketplace. Specifically, we include indicators for the Telecommunications Act of 1996 and availability of text messaging between carriers, 3G and 4G services, Skype, the iPhone, and third-party smartphone applications. In general, these are not statistically different from zero. In fact, none are statistically different from zero at the 5 % significance level. Additionally, none of these change the remaining results qualitatively or numerically.

Again, these point to the reference person of a household where these reference groups are households.

The income percentile refers to percentile in the entire sample of CUs.

The results here use the algorithmic approach to construct a price variable, but similar results are found using the alternative approach, which is also discussed in “Constructed price variables” section of Appendix.

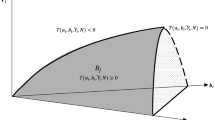

Of course the conditional logit model may suffer from independence of irrelevant alternatives assumptions. However the mixed logit does not place this a priori restriction on substitution (Train 2009).

We note Macher et al. (2013) make use of this measure as well, but do not extend or decompose it to examine heterogeneity in substitutability through time.

For a formal proof of the following statements, see Gentzkow (2007).

This is true for the first two specifications where the mixed logit suggests otherwise.

Another approach to calculating substitutability is to estimate elasticities. We have simulated changes in prices and predicted changes in consumption. Doing so points to elasticities, and incrementing a given variable can simulate the equivalent of \(\beta _\Gamma \). Doing so provides results qualitatively consistent with those presented here. Simulated elasticities are available from the authors upon request, but are not included here for length.

We also supplement the interview data with diary data for CUs that do not have expenditures in the interview data. In this case, we use variables TELRESD, UTLPROPI coded 96, and TELCELL for appropriate years.

The UCC for landline service is 270101 while the UCC for cell service is 270102.

References

Alleman, J., Rappoport, P., & Banerjee, A. (2010). Universal service: A new definition? Telecommunications Policy, 34(1), 86–91.

Bajari, P., Fox, J. T., & Ryan, S. P. (2008). Evaluating wireless carrier consolidation using semiparametric demand estimation. Quantitative Marketing and Economics, 6(4), 299–338.

BLS. (2008). Consumer expenditure survey user’s documentation. Computer software manual.

Crandall, R. W. (1988). Surprises from telephone deregulation and the AT&T divestiture. American Economic Review, 78(2), 323–327.

Department of Justice. (2008, November). Voice video and broadband: The changing competitive landscape and its impact on consumers. Computer software manual.

Economides, N., Seim, K., & Viard, V. B. (2008). Quantifying the benefits of entry into local phone service. The RAND Journal of Economics, 39(3), 699–730.

Garbacz, C., & Thompson, H. G, Jr. (2003). Estimating telephone demand with state decennial census data from 1970–1990: Update with 2000 data. Journal of Regulatory Economics, 24(3), 373–378.

Gentzkow, M. (2007). Valuing new goods in a model with complementarity: Online newspapers. American Economic Review, 97(3), 713–744.

Gentzoglanis, A., & Henten, A. (2010). Regulation and the evolution of the global telecommunications industry. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Gruber, H. (2005). The economics of mobile telecommunications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hanson, J. (2007). 24/7: How cell phones and the internet change the way we live, work, and play. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group.

HistoryOfCellPhones.net. (2008). History of cell phones. Retrieved online from http://www.HistoryOfCellPhones.net.

Klemens, G. (2010). The cellphone: The history and technology of the gadget that changed the world. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

Macher, J. T., Mayo, J. W., Ukhaneva, O., & Woroch, G. (2013). Demand in a portfoliochoice environment: The evolution of telecommunications. Washington, DC: Georgetown Center for Business and Public Policy, Georgetown University.

Miravete, E. J. (2002). Estimating demand for local telephone service with asymmetric information and optional calling plans. The Review of Economic Studies, 69(4), 943–971.

Rodini, M., Ward, M. R., & Woroch, G. A. (2003). Going mobile: Substitutability between fixed and mobile access. Telecommunications Policy, 27(5), 457–476.

Taylor, W. E., & Ware, H. (2008, December). The effectiveness of mobile wireless service as a competitive constrain on landline pricing: Was the doj wrong. Computer software manual.

Train, K. E. (2009). Discrete choice methods with simulation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Train, K. E., McFadden, D. L., & Ben-Akiva, M. (1987). The demand for local telephone service: A fully discrete model of residential calling patterns and service choices. The RAND Journal of Economics, 18(1), 109–123.

US Wireless Connections Surpass Population. (2013). CTIA—The Wireless Association. http://www.ctia.org.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge discussions with and comments of Jeremy Piger, Glen Waddell, Mark Burton, John Mayo, James Alleman and three anonymous referees as well as participants from the Transportation and Public Utilities Group meetings at the Western Economic Association Meetings and the Allied Social Science Assocation as well as participants in the University of Oregon Microeconomics Graduate Association. This work originally emanated from a group of undergraduate students who provided a lot of the background material and initial data work. We are very grateful for the contributions of Johnathan Thomas, Jon Akashi, Jason Stieber, and Ryan Churchill.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendices

1.1 Details of a household choice

As discussed in Sect. 3, the telephony service alternatives for households are (1) no phone, (2) just landline, (3) just cell phone, or (4) both. The data contain expenditures for a household from the quarter prior to the interview in many different categories defined by a universal classification code (UCC).Footnote 30 There is a unique UCC for cell phone expenditures and another unique UCC for landline expenditures. For a household with strictly-positive expenditure on the UCC of landline or cell service,Footnote 31 we record this expenditure as a choice between alternatives. That is, for an expenditure greater than zero, the household is recorded as choosing that category but recorded as not choosing that category otherwise. Choosing no phone is defined as zero expenditure in both categories while choosing both is defined as positive expenditure in both categories. The data are available dating to before the introduction of cell phone services, but all records of cell phone expenses are zero-valued in this dataset prior to 1994 even though cell phones were available about a decade earlier. For this reason, the usable data range from 1994 to 2012, a 19-year period during which the data contain more than 296,000 household choices between the defined alternatives.

1.2 Constructed price variables

In this section, we present two approaches to constructing prices from the expenditure data. The main goal of these approaches is to construct a measure of the price of a single phone. The first approach assumes all family sizes face the same prices. The second approach allows for different family sizes to face different prices with the idea being that families can get “family plans”, which offer discounts on multiple lines.

The first approach is to calculate the median expenditure by UCC for both cell and landline among CUs with family size equal to one who have nonzero expenditure in that category in a given year. This estimate assumes that CUs with family size of one only purchase one landline or one cell phone service given they choose that option. This is a reasonable assumption given that most individuals living alone do not have any reason to purchase more than one of each service and the median will certainly avoid any outliers.

The second approach allows for a different price for each option, family-size, region, year tuple. This approach is as follows:

-

1.

Take the median expenditure on an option by single-person households with positive expenditure in a category. Define this as the base price for the category, region, year triple and do this for each of these triples.

-

2.

For each family with family size greater than 1 and positive expenditure in a given category, divide the expenditure by one and calculate the absolute difference between this and the base price from step 1.

-

3.

Repeat step 2 for each integer from 1 through the family size. That is, first divide the expenditure by one, then divide it by two, and so forth.

-

4.

From these multiple prices (there are the same number of possible prices as there are individuals in the family), select the one with the smallest absolute difference between it and the base price for the option, region, year triple and call this the “temporary price”.

-

5.

For each observed family size, define the price for the option as the median of this “temporary price” among households of that family size with positive expenditure in that category. Again, this step is done once for each option, region, year triple.

-

6.

For some family sizes, there are no observations for an option. In this case, set the price equal to the price for the next family size down.

In either case, the time-series obtained through this process is less than ideal, likely due to changes in cell phone capabilities that require more extensive service plans indicating higher prices even though comparable service plans are generally decreasing in price through time. Nonetheless, our price proxies are highly correlated with the CPI categories for landline and cell phone prices, with correlation coefficients of 0.8681 and 0.7746, respectively.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thacker, M.J., Wilson, W.W. Telephony choices and the evolution of cell phones. J Regul Econ 48, 1–25 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11149-015-9274-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11149-015-9274-2