Abstract

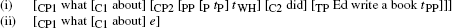

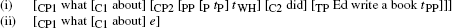

This paper examines the syntax of clauses in which prepositions undergo Swiping/Sluice-Stranding in elliptical questions like Who with? (e.g. in response to ‘She’s having an affair’). We begin by outlining characteristic properties of Swiping, noting that this involves an interrogative wh-constituent positioned in front of a focused preposition, and that the clause remnant following the preposition obligatorily undergoes a type of ellipsis traditionally termed Sluicing. We outline the recent CP shell analysis of Swiping developed by van Craenenbroeck (2010), under which a PP containing a wh-word is moved into the specifier position of an inner CP, the wh-word is moved into the specifier position of an outer CP (stranding the preposition on the edge of the inner CP), and the residual TP is deleted at PF. We discuss a range of problems with his analysis, and argue that it can be substantially improved if we adopt a more richly articulated cartographic structure for the clause periphery under which Swiped clauses contain ForceP, FocP, and FinP projections. More specifically, we argue that the wh-PP moves to the edge of FinP (with the auxiliary moving to Fino in structures involving auxiliary inversion), the preposition moves into Foco to mark it as focused, and the wh-constituent moves into Spec-ForceP to type the clause as interrogative. We claim that the obligatory Sluicing component of Swiping involves ellipsis of FinP in the PF component, and that this is required in order to repair violations of PF constraints which would otherwise arise. We show how our analysis accounts for a range of phenomena not captured under van Craenenbroeck’s original analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Throughout, we simplify representations in various ways, including by showing only those minimal and maximal projections relevant to the discussion at hand, by showing trace copies of moved constituents as t, and by not showing wh-movement transiting through Spec-vP.

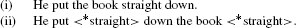

The editor observes that the robustness of the Criterial Freezing Condition is potentially undermined by examples provided by Lasnik and Saito (1992) of “subextraction out of constituents in what would now be called Criterial Freezing positions which yield relatively acceptable results,” including;

-

(i)

??Who do you wonder [which picture of] is on sale? (Lasnik and Saito 1992:102)

However, Lasnik and Saito treat such sentences as doubly degraded (??), so it is clear that some constraint is being violated here, and Criterial Freezing is a likely candidate. Violation of a single constraint on its own sometimes leads to degradation rather than downright ungrammaticality: for discussion, see Haegeman et al. (2014).

-

(i)

Although (as pointed out by the editor) there is some overlap between the Criterial Freezing and Freezing constraints, the overlap is only partial in that (for instance) Criterial Freezing blocks extraction from an in situ constituent in a criterial position, and Freezing blocks extraction from a moved constituent in a non-criterial position. Hence we treat then as potentially distinct constraints throughout.

See (28a) for an example of licit extraction out of a PP containing straight. An anonymous reviewer points out that the ungrammaticality of (15b) could be accounted for under van Craenenbroek’s analysis by supposing that straight is stranded in Spec-CP and thereby interpreted as being focused. It would then follow that straight could not be focused in the context in which it occurs in (15b) because (15b) is a response to (15a), and straight is given in (15a). However, even in a more felicitous context, independent principles would arguably rule out the possibility of a discontinuous string like straight…from being focused.

However, as anonymous reviewers point out, the relevant observations could be accommodated under van Craenenbroek’s analysis if parenthetical adjuncts are associated with comma intonation, and if the specifier of CP2 is interpreted as focused but not a parenthetical adjunct adjoined to it. We note in passing that sentences like (16) pose a severe problem for Merchant’s (2002) analysis of Swiping as involving adjunction of a wh-word to a preposition—as do sentences like (11) and (13) which involve Swiping of a wh-phrase rather than of a wh-word.

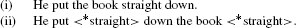

The auxiliary inversion problem also arises in other analyses which take Swiping to involve Sluicing of TP (e.g. Merchant 2002; Nakao 2009; Aelbrecht 2010), and a number of (more or less ad hoc) ways have been suggested for dealing with the problem (see e.g. Lasnik 1999, 2001, 2013; Boeckx and Stjepanovic 2001; Merchant 2001, 2008). One is to suppose that Subject-Auxiliary Inversion/SAI takes place after Sluicing: TP-deletion would then remove the auxiliary to be inverted. Another is to posit that SAI is triggered by a feature on the auxiliary rather than by a feature on C, with the consequence that the feature on the auxiliary requiring it to be inverted is deleted when the auxiliary is deleted. A third is to take SAI to involve movement of a feature on T to C. An anonymous reviewer suggests a fourth possibility, whereby P adjoins to the empty Co in CP1 to derive (i), and Sluicing then deletes CP2, deriving (ii)

However, this solution is problematic for two reasons. Firstly, van Craenenbroeck argues that the locus of Focus is CP2, so an analysis like (i,ii) would fail to account for how the preposition comes to be focused when Swiped. Secondly, CP1 is taken to be the locus of Force by van Craenenbroeck, so it is not obvious what would drive movement of the preposition to the edge of an interrogative Force projection, since the preposition is not interrogative.

Huddleston (1994) argues that (illocutionary) force is a pragmatic rather than a syntactic notion, and that its syntactic counterpart is clause type (see also Cheng 1991); this would argue in favor of replacing ForceP by TypP. However, we continue to use the label ForceP here because it is widely adopted in the cartographic literature.

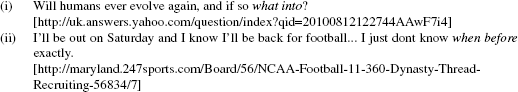

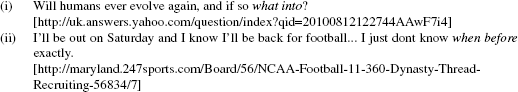

We employ the term ‘complex preposition’ here to denote a phrasal expression comprising more than one independent word (e.g. because of, in spite of, instead of, on top of). Our use of this term thus differs from that of Merchant (2002; fn. 5), since he analyses some single-word prepositions like above, before, between, despite, during, into, regarding, and underneath as complex prepositions (although he does not say what the criteria for this classification are). There seems to be no ban on the single-word prepositions which Merchant classifies as complex undergoing Swiping, as the following internet-sourced examples illustrate:

See also further counterexamples to Merchant’s story about single-word complex prepositions in Beecher (2007). By contrast, we are not aware of any examples of Swiping with phrasal prepositions.

The editor notes that the idea that straight cannot be stranded by head movement gains independent empirical support from the observation that straight cannot occur in verb-particle constructions in which the particle is to the left of the object, regardless of whether straight is placed to the left of the particle or to the right of the object:

See den Dikken (1995) on the idea that straight prevents particle incorporation.

It may be that structures such as the following provide further motivation for heads being focused by adjoining to Foco:

-

(i)

John has a job, but he won’t tell me what doing. (Hartman 2007:48)

Sentences like (i) can be treated as instances of head focusing, if the VP doing what moves to the edge of FinP, then doing adjoins to Foco, and what moves to Spec-ForceP. However, see Larson (2013) for an alternative analysis.

-

(i)

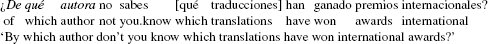

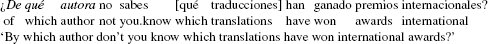

An anonymous reviewer suggests that the robustness of the Edge Condition and the Freezing Constraint is undermined by potential counterexamples like the Spanish sentence below, attributed to Esther Torrego in Chomsky (1986:26):

-

(i)

At first sight, it might appear that the italicised wh-phrase has been extracted from within the bracketed fronted wh-phrase located on the edge of a CP phase, in apparent violation of the Edge and Freezing conditions. However, Gallego (2007:340) argues that in such sentences, “The alleged sub-extracted PP is actually base generated outside the embedded wh-phrase, as a PP dependent of the matrix verb: an aboutness phrase.” He amasses a considerable body of evidence in defence of this view (Gallego 2007:335–354) and additional support is provided by Boeckx (2012:131–132).

-

(i)

An alternative account of the repair function of Sluicing in cases of Swiping may be achievable within the phase-based account of linearization developed in Fox and Pesetsky (2003, 2005) and Drummond et al. (2010). One story along these lines would be that by the end of the FinP phase, the preposition is linearized as preceding its wh-complement, but subsequent movement operations result in the complement preceding the preposition, leading to contradictory linearization statements. Sluicing of FinP (and of the linearization statements relating to it) eliminate this ordering contradiction. See Sect. 5.2 for related discussion.

The contrast between (34) and (35a) could in principle be accounted for in selectional terms, e.g. by positing that Forceo in a Swiped clause can have a ModP complement but not a TopP complement. However (as noted by an anonymous referee) it would be preferable to follow Abels (2012:251) in positing that the relative ordering of peripheral projections is predictable from locality constraints on movement, and that peripheral projections “do not need to be ordered by selectional requirements but can be merged freely. Derivations where the heads are merged in the wrong order will be filtered out because the heads will then not be able to attract their appropriate specifiers without violating locality” (Abels, ibid.). An anonymous reviewer suggests that the contrast between (34) and (35) could alternatively be handled by positing that the intervening (underlined) material in (35a) is adjoined to FocP. Another anonymous referee asks what bars Sluicing in a clause like that italicised below:

-

(i)

∗He says he is going to give away all his possessions, but I’m not sure when his Rolls Royce.

One possible answer is that FinP in (ii) is the complement of a Top head whose specifier is the fronted topic his Rolls Royce, and Top heads (unlike Focus heads) do not trigger Sluicing. However, this cannot be the whole story, since even an unsluiced structure like (iii) is ungrammatical:

-

(i)

∗I’m not sure when his Rolls Royce he’s going to give away.

If the italicised clause in (ii) derives from a structure loosely paraphraseable as He is going to give away his Rolls Royce when, it may be that there is an intervention violation incurred by the fronted wh-constituent moving across the fronted tropicalized argument his Rolls Royce.

-

(i)

The editor points out that the evidence for non-adjacent inversion provided by sentences like (36) and (37) is weakened by two factors. Firstly, the bold-printed and italicized strings in some cases may form a single constituent (e.g. at no point the evening before in (37e))—and indeed Costa (2004) and Haegeman (2012) treat some such cases in this way. Secondly, in other cases the bold-printed constituents may be parenthetical adjuncts which are not syntactically integrated into the structure containing them (e.g. in your view in (36d)). However, some of the examples in (36), (37) are not amenable to either analysis: e.g. the bold-printed constituent is a fronted argument of divulge in (36f), witness in (36g) and conclude in (37a); and in (36d) the bold-printed constituent is an adverbial nominal adjunct which originates within the embedded clause and moves to the periphery of the matrix clause.

Recall from Sect. 4.1 that we are following Rizzi (1997:332; fn. 28) in assuming that force and finiteness are expressed as a single head wherever possible. Consequently, the matrix ForceP constituent in (40) will in effect be a syncretised ForceP/FinP projection. An anonymous reviewer asks why how much does not remain in situ and type the complement clause as interrogative when it moves to the embedded Spec-ForceP in (40). The answer is that the embedded clause in (40) is declarative, as we see from the possibility of having a that-clause paraphrase for it in:

-

(i)

I’m not sure how much it is predicting [that the Socialists will win by]

An interrogative phrase like how much can thus only transit through a declarative Spec-ForceP position, not remain there (because the specifier position in a declarative CP is not a criterial position for an interrogative constituent). Hence, in a sentence like:

-

(ii)

What did you say [it cost]?

the interrogative operator what transits through Spec-CP in the bracketed embedded clause but does not type the (declarative) embedded clause as interrogative, because only the final derived position of an interrogative operator is relevant to clause typing. In a different use, predict can have an interrogative complement and permit Swiping, as in:

-

(iii)

The polls correctly predicted that the Socialists would win, but they didn’t predict how much by.

-

(i)

Since Hartman argues that Swiping only occurs with interrogative wh-constituents, it is clear that by wh-feature he means what (in Sect. 5.2) we term a whQ-feature—i.e. a feature attracting a questioned wh-constituent.

The editor notes that constituents that are non-D-linked can sometimes be focused. For instance, the negative polarity item any can readily be focused, both prosodically and informationally, in a context such as the following:

-

(i)

speaker a: What have you done all day? speaker b: I haven’t done anything all day.

-

(i)

However, it seems to us that the preposition can receive contrastive as well as information focus in an appropriate context, e.g.

-

(i)

We know Bond sent the package and we know where from, but we don’t know where to.

-

(i)

We use the term multiple Sluicing/Swiping to denote a sluiced/swiped clause containing multiple wh-remnants. Richards (1997:167) treats sentences like (46c) as grammatical. Merchant (2002:315; fn. 13) takes them to be ungrammatical. van Craenenbroeck (2004:27; fn. 31) reports in relation to four native speakers who judged a similar sentence that “two found it perfect, one gave it one question mark, one gave it two question marks.” Lasnik (2013) reports that an anonymous reviewer who ran a small acceptability experiment on multiple Sluicing found the mean rating to be 3.2 on a 5-point scale where 1 denotes ‘completely well formed’ and 5 ‘completely ill formed’. Lasnik himself ran a parallel experiment on multiple Sluicing using the same scale and found that the mean rating for his subjects was 2.3.

As an anonymous reviewer points out, there are potential parallels between the Extraposition analysis and earlier work claiming that in cases of Swiping even the first wh-PP undergoes rightward PP-movement followed by leftward movement of the complement of the preposition. See Kim (1997), Hasegawa (2006), Nakao et al. (2006), Nakao and Yoshida (2007) and Nakao (2009) for analyses of this ilk.

We draw the traditional distinction between yes-no questions and wh-questions, and suppose that a Force head with a whQ feature licenses only a wh-question operator (and not a yes-no question operator) as its specifier. There are clear semantic differences between the two types of question: a yes-no question asks for the truth-value of a proposition, whereas a wh-question asks for the identity of some entity. We leave open the possibility that the wh-Q feature may be reducible to two distinct features, a wh-feature and a Q-feature: see Cable (2010) on the Q-feature.

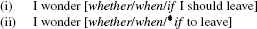

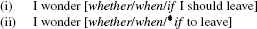

The editor suggests that contrasts like that between (i) and (ii) suggest that although if can plausibly be analyzed as a complementiser which can head a finite (but not an infinitival) CP, whether is more plausibly taken to be a wh-word which (like when) can occur as the specifier of a finite or infinitival CP:

However, we Googled dozens of authentic examples of if used in infinitival yes-no questions, including:

And the Spanish counterpart of English si ‘if’ likewise occurs not only in finite clauses but also in infinitives like:

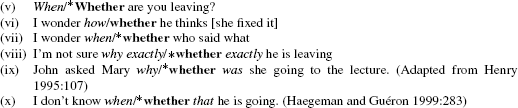

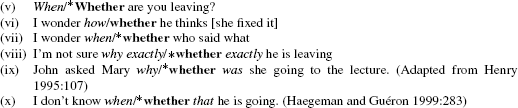

We conclude from examples like (iii, iv) that some complementisers are able to head both finite and infinitival CPs, and that whether is one of these. Moreover, there are independent reasons for treating whether as a complementiser, including the following. Unlike wh-words (but like the complementiser if), whether does not occur in root questions like (v), it cannot undergo wh-movement and so cannot be interpreted as extracted out of the bracketed embedded clause in sentences like (vi), it cannot occur in multiple wh-questions like (vii), it cannot be post-modified by exactly in sentences like (viii), it does not allow auxiliary inversion in Belfast English sentences like (ix), nor can it be followed by the complementiser that in Belfast English sentences like (x):

It should be noted, however, that wh-unconditionals (or exhaustive conditionals as they term them) are treated as a subtype of interrogative by Huddleston and Pullum (2002:14.6), and by Borsley (2011:fn. 1). It should also be noted that Abels (2007) highlights important similarities between exclamatives and interrogatives.

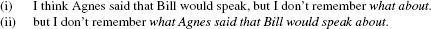

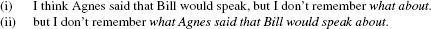

However, Chung et al. (1995:279) make the very different claim that a Sprouting/Swiping structure like the but-clause in (i) permits a long-distance reading paraphraseable as (ii):

Similarly, Sprouting in (iii) allows a long-distance reading whereby the parenthesised material is elided:

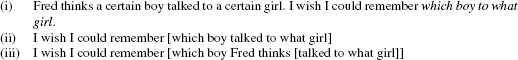

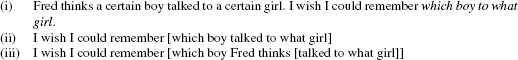

Although we lack space to discuss this issue here, we note that some researchers (e.g. Merchant 2001; Nakao 2009; Lasnik 2013) have attempted to derive cases of long-distance Sluicing from a monoclausal source. For example, Lasnik (2013) proposes that the sluiced clause italicised in (i) has the monoclausal source bracketed in (ii) rather than the biclausal source bracketed in (iii):

However, Lasnik (2013:12) concedes that the monoclausal analysis in (ii) poses the interpretive problem that “It was never actually asserted that a boy talked to a girl, merely that Fred thinks that it happened.” He suggests (ibid.) that this can be handled in terms of “a sort of accommodation” but offers no clarification of what kind of interpretive mechanism accommodation might be.

There was only one fronted wh+p structure not involving where, involving an instance of whifor in the PPCME, perhaps the result of scribal confusion with wherefor (which could have much the same sense).

Recall from Sect. 4.1 that Force and Finiteness are expressed as a single head, except where some other projection intervenes, or where FinP undergoes Sluicing. Consequently, Force and Fin will be syncretised in the embedded clause in (73), but not in the matrix clause.

References

Abels, Klaus. 2003. Successive cyclicity, antilocality and adposition stranding. PhD diss., University of Connecticut.

Abels, Klaus. 2007. Deriving selectional properties of ‘exclamative’ predicates. In Interfaces and interface conditions, language, context and cognition, ed. Andreas Späth, 115–140. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Abels, Klaus. 2012. The Italian left periphery: a view from locality. Linguistic Inquiry 43: 229–254.

Aelbrecht, Lobke. 2009. You have the right to remain silent. The syntactic licensing of ellipsis. PhD diss., HUBrussel.

Aelbrecht, Lobke. 2010. The syntactic licensing of ellipsis. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Baltin, Mark. 2010. The nonreality of doubly filled Comps. Linguistic Inquiry 41: 331–335.

Beecher, Henry. 2007. Pragmatic inference in the interpretation of sluiced prepositional phrases. CamLing 2007: 9–16.

Boeckx, Cedric. 2007. Understanding minimalist syntax. Oxford: Blackwell.

Boeckx, Cedric. 2012. Syntactic islands. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Boeckx, Cedric, and Howard Lasnik. 2006. Intervention and repair. Linguistic Inquiry 37: 150–155.

Boeckx, Cedric, and Sandra Stjepanovic. 2001. Head-ing towards PF. Linguistic Inquiry 32: 345–355.

Borsley, Robert. 2011. Constructions, functional heads and comparative correlatives. Empirical Issues in Syntax and Semantics 8: 7–20.

Bošković, Željko. 2011. Rescue by PF deletion, traces as (non)interveners, and the that-trace effect. Linguistic Inquiry 42: 1–44.

Branigan, Phil. 2005. The phase-theoretic basis for Subject-Aux Inversion. Ms. Memoral University.

Cable, Seth. 2010. Against the existence of pied-piping: evidence from Tlingit. Linguistic Inquiry 41: 367–386.

Chaves, Rui. 2012. On the grammar of extraction and coordination. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 30: 465–512.

Cheng, Lisa. 1991. On the typology of wh questions. PhD diss., MIT.

Chomsky, Noam. 1964. Current issues in linguistic theory. The Hague: Mouton.

Chomsky, Noam. 1972. Some empirical issues in the theory of transformational grammar. In Goals of linguistic theory, ed. Paul Stanley Peters, 63–130. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Chomsky, Noam. 1986. Barriers. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The minimalist program. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by phase. In Ken Hale: a life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 1–52. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2005. Three factors in language design. Linguistic Inquiry 36: 1–22.

Chomsky, Noam. 2008. On phases. In Foundational issues in linguistic theory. Essays in honor of Jean-Roger Vergnaud, eds. Robert Freidin, Carlos P. Otero, and Maria Luisa Zubizarreta, 133–166. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2013. Problems of projection. Lingua 130: 33–49.

Chomsky, Noam, and Howard Lasnik. 1977. Filters and control. Linguistic Inquiry 8: 425–504.

Chung, Sandra, William A. Ladusaw, and James McCloskey. 1995. Sluicing and logical form. Natural Language Semantics 3: 239–282.

Chung, Sandra, William Ladusaw, and James McCloskey. 2011. Sluicing: between structure and inference. In Representing language: essays in honor of Judith Aissen, eds. Rodrigo Gutiérrez-Bravo, Line Mikkelsen, and Eric Potsdam, 31–50. California Digital Library eScholarship Repository. University of California, Santa Cruz: Linguistic Research Center.

Collins, Chris. 2007. Home, sweet home. NYU Working Papers in Linguistics 1: 1–34.

Collins, Chris, and Paul M. Postal. 2012. Imposters: a study of pronominal agreement. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Collins, Chris, and Andrew Radford. 2013. Gaps, ghosts and gapless relatives in spoken English. http://ling.auf.net/lingbuzz/001699?_s=XKX5vnJ5rPoMkCix&_k=l-QQKtRZXbktNQKA.

Costa, João. 2004. A multifactorial approach to adverb placement: assumptions, facts and problems. Lingua 114: 711–753.

van Craenenbroeck, Jeroen. 2004. Ellipsis in Dutch dialects. PhD diss., Leiden University.

van Craenenbroeck, Jeroen. 2010. The syntax of ellipsis: evidence from Dutch dialects. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

van Craenenbroeck, Jeroen, and Marcel den Dikken. 2006. Ellipsis and EPP repair. Linguistic Inquiry 37: 653–664.

van Craenenbroeck, Jeroen, and Anikó Lipták. 2006. The cross-linguistic syntax of sluicing: evidence from Hungarian relatives. Syntax 9: 248–274.

Culicover, Peter. 1999. Syntactic nuts: hard cases, syntactic theory, and language acquisition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Culicover, Peter W., and Ray Jackendoff. 2005. Simpler syntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

den Dikken, Marcel. 1995. Particles: on the syntax of verb-particle, triadic and causative constructions. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

den Dikken, Marcel, and Anastasia Giannakidou. 2002. From hell to polarity: aggressively non-D-linked wh-phrases as polarity items. Linguistic Inquiry 33: 31–61.

Drummond, Alex, Norbert Hornstein, and Howard Lasnik. 2010. A puzzle about P-stranding and a possible solution. Linguistic Inquiry 41(4): 689–692.

Endo, Yoshio. 2007. Locality and information structure. A cartographic approach to Japanese. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Fábregas, Antonio, and Ángel L. Jiménez-Fernández. 2012. Extraction from fake adjuncts and the nature of secondary predicates. Ms. Universities of Tromsø and Sevilla.

Fox, Danny, and Howard Lasnik. 2003. Successive-cyclic movement and island repair: the difference between sluicing and VP-ellipsis. Linguistic Inquiry 34: 143–154.

Fox, Danny, and David Pesetsky. 2003. Cyclic linearization and the typology of movement. Ms., MIT.

Fox, Danny, and David Pesetsky. 2005. Cyclic linearization of syntactic structure. Theoretical Linguistics 31: 1–45.

Friedmann, Naama, Adriana Belletti, and Luigi Rizzi. 2009. Relativized minimality: types of intervention in the acquisition of A-bar dependencies. Lingua 119: 67–88.

Gallego, Ángel. 2007. Phase theory and parametric variation. PhD diss., Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

Gengel, Kirsten. 2006. Contrastivity and ellipsis. In LingO, University of Oxford postgraduate conference in linguistics, Oxford, England, eds. Lisa Mackie and Anna McNay.

Grohmann, Kleanthes. 2003. Prolific domains. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Haegeman, Liliane. 1996. Verb second, the split CP and null subjects in early Dutch finite clauses. GenGenP 2: 133–175. Available at http://ling.auf.net/lingBuzz/001059..

Haegeman, Liliane. 2003. Notes on long adverbial fronting in English and the left periphery. Linguistic Inquiry 34: 640–649.

Haegeman, Liliane. 2006. Conditionals, factives and the left periphery. Lingua 116: 1651–1669.

Haegeman, Liliane. 2012. Main clause phenomena and the left periphery. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Haegeman, Liliane, and Jacqueline Guéron. 1999. English grammar. Oxford: Blackwell.

Haegeman, Liliane, Ángel Jiménez-Fernández, and Andrew Radford. 2014. Deconstructing the subject condition in terms of cumulative constraint violation. The Linguistic Review 31: 73–150.

Hartman, Jeremy. 2007. Focus, deletion, and identity: investigations of ellipsis in English. B.A. thesis, Harvard University.

Hartman, Jeremy, and Ruixi Ressi Ai. 2009. A focus account of Swiping. In Selected papers from the 2006 Cyprus Syntaxfest, eds. Kleanthes K. Grohmann and Phoevos Panagiotidis, 92–122. Accessed from http://web.mit.edu/hartmanj/www/Swiping.pdf..

Hasegawa, Hiroshi. 2006. On Swiping. English Linguistics 23: 433–445.

Henry, Alison. 1995. Belfast English and Standard English: dialect variation and parameter setting. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hiraiwa, Ken, and Shinichiro Ishihara. 2012. Syntactic metamorphosis: clefts, sluicing and in-situ focus in Japanese. Syntax 15: 142–180.

Hofmeister, Philip. 2012. Effects of processing on the acceptability of ‘frozen’ extraposed constituents. Ms., University of Essex.

Hornstein, Norbert, Howard Lasnik, and Juan Uriagereka. 2003. The dynamics of islands: speculations on the locality of movement. Linguistic Analysis 33: 149–175.

Huang, Cheng-Teh James. 1982. Logical relations in Chinese and the theory of grammar. PhD diss., MIT.

Huddleston, Rodney. 1994. The contrast between interrogatives and questions. Journal of Linguistics 30: 411–439.

Huddleston, Rodney, and Geoffrey K. Pullum. 2002. The Cambridge grammar of the English language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hudson, Richard. 2003. Trouble on the left periphery. Lingua 113: 607–642.

İnce, Atakan. 2012. Fragment answers and islands. Syntax 15: 181–214.

Johnson, Kyle. 2001. What VP ellipsis can do, and what it can’t, but not why. In The handbook of contemporary syntactic theory, eds. Mark Baltin and Chris Collins, 439–479. Oxford: Blackwell.

Jurka, Johannes, Chizuru Nakao, and Akira Omaki. 2011. It’s not the end of the CED as we know it: revisiting German and Japanese subject islands. In Proceedings of the 28th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics, eds. Mary Byram Washburn et al., 124–132. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

Kennedy, Christopher, and Jason Merchant. 2000. Attributive comparative deletion. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 18: 89–146.

Kim, Jeong-Seok. 1997. Syntactic focus movement and ellipsis: a minimalist approach. PhD diss., University of Connecticut, Storrs.

Koopman, Hilda. 2000. The syntax of specifiers and heads. London: Routledge.

Koopman, Hilda, and Anna Szabolsci. 2000. Verbal complexes. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kroch, Anthony, and Ann Taylor, eds. 2000. The Penn-Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Middle English, 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Department of Linguistics, University of Pennsylvania.

Larson, Bradley. 2013. Generalized Swiping. http://ling.umd.edu/~bradl/publications/generalizedSwiping.pdf.

Lasnik, Howard. 1995. A note on pseudogapping. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 27: 143–163.

Lasnik, Howard. 1999. Pseudogapping puzzles. In Fragments: studies in ellipsis and gapping, eds. Elias Benmamoun and Shalom Lappin, 141–174. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lasnik, Howard. 2001. When can you save a structure by destroying it? In Proceedings of the 31st Annual Meeting of the North East Linguistic Society, eds. Minjoo Kim and Uri Strauss, 301–320. Amherst: GLSA publications.

Lasnik, Howard. 2002. Long distance interpretations of Sluicing? Lecture handout, Leiden University, May 2002 (cited in Nakao 2009:71).

Lasnik, Howard. 2013. Multiple sluicing in English? Syntax 17(1): 1–20.

Lasnik, Howard, and Mamoru Saito. 1992. Move α: conditions on its application and output. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Lobeck, Anne. 1995. Ellipsis: functional heads, licensing, and identification. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Merchant, Jason. 1999. The syntax of silence—sluicing, islands, and identity of ellipsis. PhD diss., UCSC.

Merchant, Jason. 2001. The syntax of silence: sluicing, islands, and the theory of ellipsis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Merchant, Jason. 2002. Swiping in Germanic. In Studies in comparative Germanic syntax, eds. Werner Abraham and Jan-Wouter Zwart, 295–321. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Merchant, Jason. 2003. Subject-auxiliary inversion in comparatives and PF output constraints. In The interfaces: deriving and interpreting omitted structures, eds. Kerstin Schwabe and Susanne Winkler, 55–77. Amsterdam: Benjamin.

Merchant, Jason. 2004. Fragments and ellipsis. Linguistics and Philosophy 27: 661–738.

Merchant, Jason. 2006. Sluicing. In The Syntax companion, eds. Martin Everaert and Henk van Riemsdijk, 269–289. London: Blackwell.

Merchant, Jason. 2008. Variable island repair under ellipsis. In Topics in ellipsis, ed. Kyle Johnson, 132–153. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Müller, Gereon. 2010. On deriving CED effects from the PIC. Linguistic Inquiry 41: 35–82.

Nakao, Chizuru. 2009. Island repair and non-repair by PF strategies. PhD diss., University of Maryland.

Nakao, Chizuru, Hajime Ono, and Masaya Yoshida. 2006. When a complement PP goes missing: a study on the licensing of Swiping. West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 25: 297–305.

Nakao, Chizuru, and Masaya Yoshida. 2007. Not-so-propositional islands and their implications for Swiping. In Western Conference on Linguistics (WECOL), 2006, eds. Erin Bainbridge and Brian Agbayani, 322–333. University of California, Fresno.

Nunes, Jairo, and Juan Uriagereka. 2000. Cyclicity and extraction domains. Syntax 3: 20–43.

Park, Bum-Sik. 2005. Focus, parallelism, and identity in ellipsis. PhD diss., University of Connecticut, Storrs.

Pesetsky, David. 1987. Wh-in-situ: movement and unselective binding. In The representation of (in)definiteness, eds. Eric J. Reuland and Alice G. B. ter Meulen, 98–129. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Rackowski, Andrea, and Norvin Richards. 2005. Phase edge and extraction: a Tagalog case study. Linguistic Inquiry 36: 565–599.

Radford, Andrew. 1993. Head-hunting: on the trail of the nominal Janus. In Heads in grammatical theory, eds. Greville G. Corbett, Norman C. Fraser, and Scott McGlashan, 73–111. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rawlins, Kyle. 2008. (Un)conditionals: an investigation in the syntax and semantics of conditional structures. PhD diss., UCSC.

Richards, Norvin. 1997. What moves where when in which language? PhD diss., MIT.

Richards, Norvin. 2001. Movement in language: interactions and architectures. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

van Riemsdijk, Henk. 1982. A case study in syntactic markedness: the binding nature of prepositional phrases. Dordrecht: Foris.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1996. Residual verb second and the wh-criterion. In Parameters and functional heads, eds. Adriana Belletti and Luigi Rizzi, 63–90. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The fine structure of the left periphery. In Elements of grammar, ed. Liliane Haegeman, 281–337. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Rizzi, Luigi. 2001. On the position Int(errogative) in the left periphery of the clause. In Current studies in Italian syntax: essays offered to Lorenzo Renzi, eds. Guglielmo Cinque and Giampolo Salvi, 286–296. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Rizzi, Luigi. 2004. Locality and left periphery. In Structures and beyond, ed. Adriana Belletti, 223–251. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rizzi, Luigi. 2010. On some properties of criterial freezing. In The complementizer phase: subjects and operators, ed. E. Phoevos Panagiotidis, 17–32. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rizzi, Luigi, and Ur Shlonsky. 2007. Strategies of subject extraction. In Interfaces + recursion = language? Chomsky’s minimalism and the view from syntax-semantics, eds. Hans-Martin Gartner and Uli Sauerland, 115–160. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Roberts, Ian. 1991. Excorporation and minimality. Linguistic Inquiry 22: 209–218.

Roberts, Ian. 2010. Agreement and head movement: clitics, incorporation, and defective goals. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Rosen, Carol. 1976. Guess what about? In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the North East Linguistic Society, Vol. 6, 205–211.

Ross, John R. 1969. Guess who? In Papers from the Regional Meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society, Vol. 5, 252–286.

Ross, John R. 1986. Infinite syntax. Norwood: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Sheehan, Michelle. 2010. The resuscitation of CED. NELS 40.

Sheehan, Michelle. 2013. Some implications of a copy theory of labelling. Syntax 16(4): 362–396.

Sabel, Joachim. 2002. A minimalist analysis of syntactic islands. The Linguistic Review 19: 271–315.

Sobin, Nicolas. 2003. Negative inversion as nonmovement. Syntax 6: 183–222.

Starke, Michal. 2001. Move dissolves into Merge: a theory of locality. PhD diss., University of Geneva. http://theoling.auf.net/papers/starke_michal/.

Stepanov, Arthur. 2007. The end of CED? Minimalism and extraction domains. Syntax 10: 80–126.

Takahashi, Daiko. 1994. Sluicing in Japanese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 3: 265–300.

Taylor, Ann, Anthony Warner, Susan Pintzuk, and Frank Beths. 2003. The York-Toronto-Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Old English Prose. University of York. Distributed through the Oxford Text Archive.

Taylor, Ann, Arja Nurmi, Anthony Warner, Susan Pintzuk, and Terttu Nevalainen. 2006. The Parsed Corpus of Early English Correspondence. Annotated by Ann Taylor, Arja Nurmi, Anthony Warner, Susan Pintzuk, and Terttu Nevalainen. Compiled by the CEEC Project Team. York: University of York and Helsinki: University of Helsinki. Distributed through the Oxford Text Archive.

Travis, Lisa. 1984. Parameters and effects of word order variation. PhD diss., MIT.

Truswell, Robert. 2007. Extraction from adjuncts and the structure of events. Lingua 117: 1355–1377.

Truswell, Robert. 2009. Preposition stranding, passivisation, and extraction from adjuncts in Germanic. Linguistic Variation Yearbook 8: 131–177.

Truswell, Robert. 2011. Events, phrases, and questions. London: Oxford University Press.

Uriagereka, Juan. 1999. Multiple spell-out. In Working minimalism, eds. Samuel Epstein and Norbert Hornstein, 251–282. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Wexler, Ken, and Peter W. Culicover. 1980. Formal principles of language acquisition. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Yoshimoto, Keisuke. 2012. The left periphery of CP phases in Japanese. Acta Linguistica Hungarica 59: 339–384.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for help from Peter Culicover, Chris Cummins, Liliane Haegeman, Jeremy Hartman, Ángel Jiménez-Fernández, Howard Lasnik, Jim McCloskey, Jason Merchant, Peter Sells, anonymous NLLT reviewers and the editors (especially Marcel den Dikken). We would also like to thank David Adger, Doug Arnold, Martin Atkinson, Bob Borsley, Chris Collins, Peter Culicover, Nigel Harwood, Roger Hawkins, Alison Henry, Caroline Heycock, Philip Hofmeister, Mike Jones, Richard Larson, Adam Ledgeway, Jason Merchant, Louisa Sadler, Carson Schütze, Neil Smith, Andy Spencer and Tom Roeper for giving us their judgments on the acceptability of the examples of Pseudoswiping in (62) in the main text, and Alison Henry for her judgment of the Belfast English sentences in (25) as well. Special thanks are due to Philip Hofmeister for collecting Mechanical Turk data for us, and to Susan Pintzuk for researching fronted wh+p structures in earlier varieties of English. Andrew Radford is grateful to the University of Essex for a period of leave which supported his contribution to the research reported here. Eiichi Iwasaki is grateful to Akira Morita for making research facilities at Waseda University available to him.