Abstract

This paper provides an explanation for the unexpected ban on preposition stranding by wh-R-pronouns under sluicing in Dutch. After showing that previous prosodic and syntactic explanations are untenable, we propose that the observed ban is a by-product of an EPP condition that applies in the PP domain in Dutch. Our analysis revolves around the idea that ellipsis bleeds EPP-driven movement, an idea that already has empirical support from independent patterns of ellipsis found in English and in other structural domains in Dutch. Our claim is that: (1) R-pronominalization involves a pronominal argument of P moving to the periphery of its extended PP domain (PlaceP) in order to satisfy a PP-internal EPP condition, (2) this EPP-driven movement is bled under sluicing, and (3) because SpecPlaceP is the ‘escape hatch’ through which R-pronouns must move in order to exit the PP domain to form preposition stranding configurations, bleeding the EPP-driven movement of R-pronouns to SpecPlaceP therefore precludes R-pronouns from undergoing the wh-movement required to form a sluicing configuration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Sluicing (Ross 1969) refers to the configuration in which all but the wh-phrase of an embedded wh-question appears to go ‘missing’ (1). The prevailing view in mainstream generative circles is that sluicing configurations are generated by clausal ellipsis, which renders unpronounced an otherwise full-fledged TP (2) (Ross 1969; Merchant 2001).

(1) | John laughed at someone, but I don’t know who. |

(2) | John laughed at someone, but I don’t know [CP who1

[ |

According to this analysis, the wh-phrase in sluicing undergoes A′-movement from a position within the ellipsis site. As a result, sluicing is predicted to be sensitive to the syntactic constraints on wh-movement in any given language L. Merchant (2001) demonstrates that this prediction is borne out for at least one constraint that varies across languages; namely, whether or not preposition stranding wh-movement is permitted in L. Merchant observes that languages that ordinarily permit preposition stranding wh-movement (e.g., English, Frisian, Swedish, Norwegian, Danish, Icelandic) also permit such movement under sluicing (see (1)), whereas language that ordinarily disallow preposition stranding wh-movement (e.g., Greek, Yiddish, Russian, Polish, Czech, Bulgarian, Slovene, Persian, Catalan, French, Spanish, Italian, Hebrew, Moroccan Arabic, and Basque) also disallow such movement under sluicing (3).

(3) | P-pied-piping wh-movement | |||||||||||

a. | Me | pjon | milise? | Greek (Merchant 2001, 94) | ||||||||

with | who | she.spoke | ||||||||||

‘Who did she speak with?’ | ||||||||||||

P-stranding wh-movement | ||||||||||||

b. | * | Pjon | milise | me? | ||||||||

who | she.spoke | with | ||||||||||

Sluicing | ||||||||||||

c. | I | Anna | milise | me | kapjon, | alla | dhe | ksero | *(me) | pjon? | ||

the | Anna | spoke | with | someone | but | not | I.know | with | who | |||

‘Anna spoke with someone, but I don’t know with who.’ | ||||||||||||

This observation is encapsulated in the preposition stranding generalization (Merchant 2001, 92):

(4) | A language L will allow preposition stranding under sluicing iff L allows preposition stranding under regular wh-movement. |

Researchers have observed apparent exceptions to this generalization, however. Some languages that disallow P-stranding under regular wh-movement, such as Spanish, Italian and French (Merchant 2001; Vicente 2008), Brazilian Portuguese (Rodrigues et al. 2009), and Polish (Szczegielniak 2008), allow for prepositionless wh-remnants under sluicing (5). In addition, a lexically restricted set of English prepositions that ordinarily resist stranding can indeed be stranded under sluicing (6) (Ross 1969; van Craenenbroeck 2004; Fortin 2007).

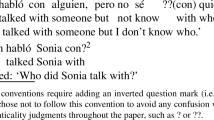

(5) | a. | * | [Qué | chica]1 | ha | habladó | Juan | [PP | con | t1]? | Spanish | |

which | girl | has | talked | Juan | with | |||||||

‘Who has Juan talk with?’ | ||||||||||||

b. | Juan | ha | hablado | con | una | chica | pero | no | sé | cuál. | ||

Juan | has | talked | with | a | girl | but | not | know | which | |||

‘Juan talked with a girl, but I don’t know which.’ | (Rodrigues et al. 2009, ex. 4) | |||||||||||

(6) | a. | * | Whose1 wishes did Terry get married [PP against t1]? | |

b. | Terry got married against someone's wishes, but I don't know whose (wishes). | |||

(Fortin 2007, ex. 405b and 407b) | ||||

On closer inspection, one sees that these data do not constitute true exceptions to the preposition stranding generalization. The abovementioned studies have shown that, in each case, the elliptical clause is not syntactically isomorphic with its antecedent clause but is instead an underlying cleft or simple copular structure, in which no P-stranding occurs (7).Footnote 1

(7) | a. | Juan | hablado | con | una | chica | pero | no | sé | cuál [ |

|

|

|

|

Juan | spoke | with | a | girl | but | not | know | which | is | the | girl | with | ||

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

the | that | has | talked | Juan | ||||||||||

‘Juan talked with a girl, but I don’t know which (is the girl with whom he talked).’ | ||||||||||||||

b. | Terry got married against someone's wishes, but I don't know whose (wishes) [ | |||||||||||||

The opposite type of exception is found in Dutch (Merchant 2001, 95; Zwart 2011, 44; Hoeksema 2014; Kluck 2015). While Dutch wh-R-pronouns can strand their selecting prepositions under regular wh-movement, they cannot do this under sluicing. Kluck (2015) refers to this exception as ‘Merchant’s Wrinkle’. This contrast is shown in the examples in (8), in which the wh-R-pronoun is marked with a subscripted ‘R’.

(8) | He is looking at something, … | Dutch | ||||||||||

a. | maar | ik | weet | niet | waarR1 | hij | [PP | naar | t1 ] | kijkt. | ||

but | I | know | not | where | he | at | looks | |||||

‘but I don’t know what he is looking at.’ | ||||||||||||

b. | maar | ik | weet | niet | {waar / * | waarR }. | ||||||

but | I | know | not | where | where | |||||||

i. | * | ‘He is looking at something, but I don’t know what he is looking at.’ | ||||||||||

ii. | ‘He is looking at something, but I don’t know where he is looking at something.’ | |||||||||||

We have added the subscripted ‘R’ to the wh-R-pronoun to distinguish it from the ‘true’ locative wh-pronoun, with which the wh-R-pronoun is homophonous. Although the wh-R-pronoun cannot appear as the sole remnant of sluicing, the true locative pronoun can, as (8b) shows. In this case, the ‘sprouting-type’ interpretation in (8bii) is obtained, as the locative pronoun is interpreted as an adjunct to VP in the elliptical clause. On this interpretation, no preposition stranding is involved.

It should be mentioned that the same pattern is observed in German (Merchant 2001, 95), another language in which pronominal complements of certain prepositions are obligatorily realized as locative pronouns. Like in Dutch, wh-R-pronouns can also strand their preposition under regular wh-movement in certain varieties of German, yet they only have a locative interpretation when they appear as a ‘bare’ remnant of sluicing (9).Footnote 2

(9) | He counted on something, … | German | ||||||||||

a. | aber | ich | weiß | nicht | woR1 | er | [PP | mit t1 ] | gerechnet | hat. | ||

but | I | know | not | where | he | with | counted | has | ||||

‘but I don’t know what he counted on.’ | ||||||||||||

b. | aber | ich | weiß | nicht | {wo | / * woR}. | ||||||

but | I | know | not | where | where | |||||||

i | * | ‘He counted on something, but I don’t know what he counted on.’ | ||||||||||

ii. | ‘He counted on something, but I don’t know where he counted on something.’ | |||||||||||

The pattern exemplified in (8) and (9) completes the empirical picture for possible combinations of preposition stranding behavior under regular wh-movement and under sluicing, as Table 1 shows. This pattern is significant because the answer offered to explain its converse pattern (i.e., the third column in Table 1)—namely, that the preposition stranding under sluicing is only apparent, and therefore that the preposition stranding generalization is not violated—cannot apply here in the Dutch case, as preposition stranding should be no obstacle for sluicing, and therefore need not be circumvented. Consequently, a new and independent analysis of this pattern is required. The purpose of this paper is to shed light on this pattern and offer an analysis for it, via an extensive case study of Dutch. While we hope that our results will extend without much modification for German, we leave the suitability of our proposal for this language for future research.

The paper is structured as follows. In Sect. 2, we provide background information on preposition stranding in Dutch and its availability under sluicing, considering observations from the literature as well as the results of an acceptability judgment study we have carried out. In Sect. 3, we rule out appealing to prosody to explain ‘Merchant’s Wrinkle’ by showing that, at least from a prosodic perspective, R-pronouns are licit remnants of sluicing. In Sect. 4, we first refute Kluck’s (2015) syntactic explanation of ‘Merchant’s Wrinkle’ before proposing our own account. Our analysis revolves around the idea that sluicing bleeds preposition stranding in Dutch.

2 Dutch R-pronouns

In this section, we first provide some background information on the form, distribution, and meaning of R-pronouns and related phenomena in Dutch, before elaborating on how R-pronominalization interacts with sluicing in Dutch. Because only the basic information needs to be conveyed for now, we gloss over many technical syntactic details in this section. A deeper and more technical picture of the Dutch locative PP is presented in Sect. 4, in which we outline our analysis.

2.1 Dutch PPs, R-pronouns, P-stranding, and P-pied-piping

Dutch R-pronouns are non-human, pronominal complements of spatial prepositions that are realized as locative pronouns but display the syntactic hallmarks of nominal expressions. They are called R-pronouns because all Dutch locative pronouns contain the phoneme r (e.g., waar ‘where’, daar ‘there’, ergens ‘somewhere’, hier ‘here’) (van Riemsdijk 1978). In addition to being realized in a locative form, an R-pronoun must linearly precede its preposition (10). The prevailing view is that the observed ‘R-pronoun > P’ word order arises from A′-movement of the R-pronoun. Thus, an R-pronoun necessarily strands its preposition. When stranding occurs PP-internally, the R-pronoun A′-moves to the specifier a functional projection within the PP domain (11) (Van Riemsdijk 1978; Koopman 2000; Den Dikken 2010; for alternative views, see Bennis and Hoekstra 1984; Müller 2000; Abels 2003; and Noonan 2017).

(10) | a. | Ik | heb | de | bal | daarRop | gelegd. | ||

I | have | the | ball | there.on | put | ||||

b. | * | Ik | heb | de | bal | op | daarR | gelegd. | |

I | have | the | ball | on | there | put | |||

‘I have put the ball on it.’ | |||||||||

(11) | For (10a): | … |

the locative PP domain in Dutch |

When stranding occurs PP-externally [see (12) and (13)], the R-pronoun escapes the PP via the specifier of the functional projection represented in (11), which is characterized as the ‘escape hatch’ from the PP domain by Koopman (2000) and Den Dikken (2010).

(12) | WaarR1 | kijkt | hij [FP t1 … [PP | naar t1]]? |

where | looks | he | at | |

‘What is he looking at?’ | ||||

(13) | De | oorlog, | daar R1 | heeft | hij | een | boek | [FP t1 … [PP | over t1]] | geschreven. |

the | war | there | has | he | a | book | about | written | ||

‘The war: that’s what he’s written a book about.’ | ||||||||||

In Dutch, PP-pied-piping involves A′-movement of the entire PP domain (Koopman 2000; Den Dikken 2010). This results in configurations such as (14) and (15) for PP domains that contain R-pronouns.

(14) | a. | WaarRnaar | kijkt | hij? |

where.at | looks | he | ||

‘What is he looking at?’ | ||||

b. | [FP WaarR1 … [PP naar t1]]2 kijkt hij t2? | |||

(15) | a. | De | oorlog, | daarRover | heeft | hij | een | boek | t2 | geschreven. |

the | war | there.over | has | he | a | book | written | |||

‘The war: that’s what he’s written a book about.’ | ||||||||||

b. | … [FP daarR1 … [PP over t1]]2 heeft hij een boek geschreven. | |||||||||

It is important to stress that R-pronominalization, and therefore preposition stranding, is confined to inanimate pronominal complements of prepositions in Dutch. Animate pronouns and non-pronominal complements cannot strand their selecting prepositions:Footnote 3

(16) | a. | Naar | wie | kijkt | hij? | /* | Wie | kijkt | hij | naar? | ||

at | who | looks | he | who | looks | he | at | |||||

‘Who is he looking at?’ | ||||||||||||

b. | Naar | welk | plaatje | kijkt | hij? | /* | Welk | plaatje | kijkt | hij | naar? | |

at | which | picture | looks | he | which | picture | looks | he | at | |||

'Which picture is he looking at?' | ||||||||||||

As mentioned in Sect. 1, despite being realized in a locative pronominal form, R-pronouns are nominal expressions, not prepositional phrases. In addition to the observation that R-pronouns are interpreted as binding the argument of a preposition (as already shown in many of the examples presented so far), support for this comes from licensing parasitic gaps: like standard A′-moved DPs, A′-moved R-pronouns can license parasitic gaps. Conversely, an A′-moved PP containing an R-pronoun cannot (17) (Zwart 2011, 217).

(17) | a. | WaarR1 | is | Tasman | zonder | [e]PG | naar | op | zoek | te | zijn t1 | naar | toe | |

where | is | Tasman | without | to | up | search | to | be | to | towards | ||||

gezeild? | ||||||||||||||

sailed | ||||||||||||||

‘What did Tasman sail towards without being on the lookout for?’ | ||||||||||||||

b. | * | WaarRnaar1 | is | Tasman | zonder | [e]PG | op | zoek | te | zijn | t1 | toe | gezeild? | |

where.to | is | Tasman | without | up | search | to | be | towards | sailed | |||||

Intended: ‘In the direction of which (land) did Tasman sail without being on the lookout for?’ | ||||||||||||||

(Zwart 2011, 217, ex. 7.245a, b) | ||||||||||||||

Another clear indication that R-pronouns and true locative pronouns are different comes from word order. Although an R-pronoun must obligatorily precede its selecting preposition (recall (10)), a true locative pronoun, if selected by a preposition, must follow it (18).

(18) | De | bus | vertrekt | van | hier. |

the | bus | departs | from | here |

R-pronominalization therefore instantiates a form-function mismatch: although an R-pronoun has the morphological form of locative expression, it shows the syntactic and semantic hallmarks of a nominal.

2.2 Dutch R-pronouns and ellipsis

As already mentioned in Sect. 1, ‘bare’ R-pronouns in Dutch cannot be remnants of sluicing. The example in (8b) (repeated in (19b)), lacks the reading that is available in its non-elliptical counterpart in (14b). In other words, the wh-remnant in sluicing cannot refer to the complement of the elided preposition naar.

(19) | He is looking at something, … | Dutch | ||||||||||

a. | maar | ik | weet | niet | waarR1 | hij | [PP | naar | t1 ] | kijkt. | ||

but | I | know | not | where | he | at | looks | |||||

‘but I don’t know what he is looking at.’ | ||||||||||||

b. | maar | ik | weet | niet | { | waar / * | waarR }. | |||||

but | I | know | not | where | where | |||||||

i. | * | ‘He is looking at something, but I don’t know what he is looking at.’ | ||||||||||

ii. | ‘He is looking at something, but I don’t know where he is looking at something.’ | |||||||||||

The availability of reading (ii) in (19b) indicates that the problem is not due to a general ban on wh-extraction of ‘locative-looking’ proforms under ellipsis. Nor is the problem due to a general ban on interpreting locative-looking proforms within remnants of sluicing as arguments: the example in (20) is acceptable and has the argumental interpretation in (19bi).

(20) | Hij | kijkt | ergens | naar, | maar | ik | weet | niet | waarRnaar. |

he | looks | somewhere | at | but | I | know | not | where.at | |

‘He is looking at something, but I don’t know what (he is looking at).’ | |||||||||

As Kluck (2015) points out, the ban on preposition stranding under sluicing extends to other types of elliptical constructions, including fragment questions (21), fragment answers (22), stripping (23), and gapping (24).

(21) | A: | Ik | ga | ergensR | een | boek | over | schrijven. | |

I | go | somewhere | a | book | about | write.inf | |||

‘I will write a book about something.’ | (Kluck 2015, ex. 12) | ||||||||

B: | Oh | ja? | WaarR*(over) | dan? | |||||

oh | yes | where.about | then | ||||||

‘Really? About what?’ | |||||||||

(22) | A: | WaarR | heb | jij | een | boek | over | geschreven? | |

where | have | you | a | book | about | written | |||

‘What have you written a book about?’ | (Kluck 2015, ex.11) | ||||||||

B: | Je | weet | wel, | daarR*(over). | |||||

you | know | aff | that.about | ||||||

‘You know, about that!’ | |||||||||

(23) | Ik | schrijf | hier r | een | boek | over | en | niet | daarr*(over). | |

I | write | this | a | book | about | and | not | that.about | ||

‘I'll write a book about this, and not that.’ | (Kluck 2015, ex.14) | |||||||||

(24) | Ik | schrijf | hierr | een | boek | over | en | jij | daarr | een | essay | *(over). |

I | write | this | a | book | about | and | you | that | an | essay | about | |

‘I'll write a book about this, and you an essay about that.’ | (Kluck 2015, ex.13) | |||||||||||

As these examples show, the argumental reading of the R-pronoun is unavailable without its selecting preposition, leading to the generalization in (25) (Kluck 2015).

(25) | Dutch R-pronouns cannot strand a preposition in an ellipsis site. |

In this paper we concern ourselves with the puzzle described in this section as formulated in (25).Footnote 4

Note that the generalization in (25) applies only to R-pronouns: it does not extend to remnants of sluicing that are non-pronominal, such as lexical DPs. It transpires that such phrases can appear as remnants of ellipsis with or without their selecting preposition, with identical acceptability, as the examples in (26) illustrate. Because lexical DPs cannot strand their selecting prepositions under regular wh-movement in Dutch (as already mentioned in the previous subsection), cases such as (26B') violate the preposition stranding generalization. This type of violation fits the description given in the third column in Table 1, and therefore instantiates the same type of violation reported in Spanish, Brazilian Portuguese, Polish, and so on (see Sect. 1): they do not instantiate a case of ‘Merchant’s Wrinkle’.

(26) | A: | WaarR | gooide | je | mee? |

where | threw | you | with | ||

lit. ‘What have you thrown with?’ (What have you thrown?) | |||||

B: | Met | een | softbal. | ||

with | a | softball | |||

B': | Een | softbal. | |||

a | softball | ||||

‘With a softball.' / ‘A softball.’ | |||||

Nevertheless, because violations of this type seen in other languages have been analyzed as involving elliptical clefts and are therefore only apparent violations, it must be determined whether Dutch cases such as (26B') also involve an elliptical clause. The acceptability judgment task reported in the next subsection does precisely this.

2.3 The results of an acceptability judgment task

To test the validity of the generalization in (25), we carried out an online acceptability judgment task targeting sluicing and fragments, using native Dutch-speaking participants. This section describes the experiment and its results.

Method. The questionnaire was an ordinal response task on a 7-point Likert scale (1 for unacceptable, 7 for acceptable). Participants were asked to rate the acceptability of elliptical and non-elliptical clauses with R-pronoun extraction. To exclude the unwanted interpretation in which an elliptical remnant corresponds to an optional sprouted locative adjunct, all stimuli were preceded by a context-setting sentence in which the location of the referent under discussion was specified (see examples (27) to (30) for illustrations). The questionnaire used a Latin-square design and contained six sub-experiments, four of which are relevant for the current study (see the list of stimuli in the Appendix). Two sub-experiments were unrelated to the current study (they contained non-elliptical sentences in which a preposition is doubled, and ellipsis with prepositions as sole items). Our filler stimuli were elliptical sentences with a missing predicate after a finite, non-modal auxiliary verb.

The experiment was run in Qualtrics. Each test stimulus was presented on a separate page, and the order of the target and filler items was randomized across all sub-experiments and participants. The questionnaire was completed by 91 native speakers, 9 of whom self-identified as bilingual (Dutch-Frisian/English/French/Mandarin/Serbian). The informants did not receive any remuneration for filling in the questionnaire, nor was any personal data retained other than their status as monolingual or bilingual speakers.

The results of the experiment were statistically analyzed in Excel (descriptive statistics) and via the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (the non-parametric equivalent of the dependent t test) in R.

Results. In Sub-experiment 1, preposition stranding in standard (i.e., embedded) sluicing was tested. This sub-experiment contained a 2 × 2 factorial design, where the factors were the presence of preposition stranding by a wh-R-pronoun (P-stranding vs. pied-piping) and the presence of ellipsis (±elliptic). There were four lexicalizations for each condition. Each token contained a different verb and preposition: kijken naar ‘look at something’, staan op ‘stand on something’, trekken aan ‘pull on something’ and gooien met ‘throw with something’.

The results of this experiment show that the generalization in (25) is valid. The [+ellipsis, P-stranding] condition [see (27a)] was judged as unacceptable, with an average of 2.5 across all lexicalizations, whereas the [+ellipsis, P-pied-piping] condition [see (27b)] was judged as acceptable, with an average of 6.6 across all lexicalizations.Footnote 5

(27) | a. | ellipsis, P-stranding: unacceptable | |||||||||||

Dirk | zit | in | de | woonkamer. | Hij | kijkt | ergens | naar, | maar | ik | weet | ||

Dirk | sits | in | the | living.room | he | looks | something | at | but | I | know | ||

niet | waarR. | ||||||||||||

not | where | ||||||||||||

b. | ellipsis, P-pied-piping: acceptable | ||||||||||||

Dirk | zit | in | de | woonkamer. | Hij | kijkt | ergens | naar, | maar | ik | weet | ||

Dirk | sits | in | the | living.room | he | looks | something | at | but | I | know | ||

niet | waarRnaar. | ||||||||||||

not | where.at | ||||||||||||

‘Dirk sits in the living room. He looks at something, but I don’t know (at) what.’ | |||||||||||||

Furthermore, the non-elliptical counterparts of these sentences, which are exemplified in (28), were judged as fully acceptable, with an average of 6.6 and 6.5 respectively.

(28) | a. | non-ellipsis, P-stranding: acceptable | |||||||||||

Dirk | zit | in | de | woonkamer. | Hij | kijkt | ergens | naar, | maar | ik | weet | ||

Dirk | sits | in | the | living.room | he | looks | something | at | but | I | know | ||

niet | waarR | hij | naar | kijkt. | |||||||||

not | where | he | at | looks | |||||||||

b. | non-ellipsis, P-pied-piping: acceptable | ||||||||||||

Dirk | zit | in | de | woonkamer. | Hij | kijkt | ergens | naar, | maar | ik | weet | ||

Dirk | sits | in | the | living.room | he | looks | something | at | but | I | know | ||

niet | waarRnaar | hij | kijkt. | ||||||||||

not | where.at | he | looks | ||||||||||

‘Dirk is sitting in the living room. He is looking at something, but I don't know <at> what he is looking <at>.’ | |||||||||||||

The average mean scores of the four conditions are presented in Fig. 1, with the elliptical conditions in blue and the non-elliptical ones in red. Applying the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test indicated that the P-pied-piping ranks (Mdn = 7) are significantly higher than the P-stranding ranks (Mdn = 2) in the ellipsis condition; V = 20.5, p < .001. The same test also indicated that the P-stranding (Mdn = 7) and the P-pied-piping (Mdn = 7) conditions did not significantly differ in the non-ellipsis condition; V = 276.5, p = .252. This confirms that Dutch speakers cannot strand a preposition in the ellipsis site under standard embedded sluicing.

In a separate sub-experiment (namely, Sub-experiment 2), each elliptical example in Sub-experiment 1 was compared to its non-elliptical cleft counterpart [see, e.g., (29)], in a 2 × 2 factorial manner, where the factors were the presence of P-stranding and the sentence type (elliptical vs. non-elliptical cleft). Just like in Sub-experiment 1, there were four lexicalizations for each condition. The purpose of this experiment was to discover whether the elliptical clauses from Sub-experiment 1 could be clefts. Our informants reported that clefting is degraded but not fully unacceptable both in the P-stranding and pied-piping conditions, as examples in (29) show. Note that cleft continuation without a preposition (i.e., … maar ik weet niet waar het is ‘I know not where it is’) is fully ungrammatical, and was therefore not tested.

(29) | a. | non-ellipsis/cleft, P-stranding: degraded acceptability | ||||||||||||

Dirk | zit | in | de | woonkamer. | Hij | kijkt | ergens | naar, | maar | ik | weet | niet | ||

Dirk | sits | in | the | living.room | he | looks | something | at | but | I | know | not | ||

waarR | het | naar | is. | (average = 3.4) | ||||||||||

where | it | at | is | |||||||||||

b. | non-ellipsis/cleft, P-pied-piped: somewhat degraded acceptability | |||||||||||||

Dirk | zit | in | de | woonkamer. | Hij | kijkt | ergens | naar, | maar | ik | weet | niet | ||

Dirk | sits | in | the | living.room | he | looks | something | at | but | I | know | not | ||

waarRnaar | het | is. | (average = 4.7) | |||||||||||

where.at | it | is | ||||||||||||

Figure 2 shows that the elliptical condition in (27) is judged as less acceptable than the cleft in the P-stranding condition, but as more acceptable than the cleft in the P-pied-piping condition. These differences are significant in both cases. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test indicated that the −ellipsis (cleft) ranks (Mdn = 3) are significantly higher than the +ellipsis ranks (Mdn = 2) in the P-stranding condition; V = 581, p < .001. The same test also indicated that the +ellipsis ranks (Mdn = 7) are significantly higher than the –ellipsis (cleft) ranks (Mdn= 5) in the P-pied-piping condition; V = 2814, p < .001. Importantly, our informants’ judgments differ also with respect to the two cleft conditions: clefts involving P-pied-piping are significantly better than those with P-stranding. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test shows that the P-pied-piping ranks (Mdn = 5) are significantly higher than the P-stranding ranks (Mdn = 3) in the non-elliptical (cleft) condition; V = 832, p < .05.

From these results we can conclude that the elided clause in configurations such as (27b) is not a cleft. Rather, the configuration in (28b), which was judged as perfectly natural, underlies (27b). This once again emphasizes the puzzle at the heart of ‘Merchant’s Wrinkle’: if sluicing with a run-of-the-mill, isomorphic elliptical clause is perfectly acceptable with pied-piped PP remnant, why isn’t the same run-of-the-mill configuration available for the P-stranding configuration in (27a)?

Notice that the clefts in (29) are truncated, insofar as their accompanying relative clause is not present. Including the relative clause in the cleft yields similar results. In a post-hoc questionnaire study with 14 native speakers, we found that the preposition cannot be stranded inside the relative clause, with waar as the pivot of the cleft (see (30a), whose average rating was 2.8). A prepositional phrase pivot fares better, but is nevertheless degraded (see (30b), whose average rating was 5.1). We must leave investigation of this intriguing observation for future research.

(30) | P-stranding in cleft with relative clause: unacceptable | (N = 14) | ||||||||||||

a. | Dirk | zit | in | de | woonkamer. | Hij | kijkt | ergens | naar, | maar | ik | weet | niet | |

Dirk | sits | in | the | living room | he | looks | something | at | but | I | know | not | ||

waar | het | is | dat | hij | naar | kijkt. | ||||||||

where | it | is | that | he | at | looks | ||||||||

‘He is looking at something, but I don’t know what it is that he is looking at.’ | ||||||||||||||

P-pied-piped in cleft with relative clause: somewhat degraded | (N = 14) | |||||||||||||

b. | Dirk | zit | in | de | woonkamer. | Hij | kijkt | ergens | naar, | maar | ik | weet | ||

Dirk | sits | in | the | living room | he | looks | something | at | but | I | know | |||

niet | waarnaar | het | is | dat | hij | kijkt. | ||||||||

not | where.at | it | is | that | he | looks | ||||||||

‘He is looking at something, but I don’t know what it is that he is looking at.’ | ||||||||||||||

Finally, in Sub-experiment 3, we tested the acceptability of lexical phrases in fragmentary elliptical clauses. This experiment employed a 2 × 2 factorial design, where the factors were the presence of P-stranding by a wh-R-pronoun (P-stranding versus P-pied-piping) and the sentence type (elliptical versus non-elliptical cleft). There were four lexicalizations for each condition. We found that the elliptical conditions are fully acceptable (see (31B) and (31B′), whose average ratings were 6.8 and 6.2 respectively) whereas the non-elliptical cleft conditions are unacceptable in both cases (see (32B) and (32B′), whose average ratings were 1.6 and 2.3 respectively).

(31) | A: | WaarR | kijkt | hij | naar? |

where | looks | he | at | ||

‘What is he looking at?’ | |||||

P-pied-piped, ellipsis: acceptable | |||||

B: | Naar | mijn | favoriete | film. | |

at | my | favorite | film | ||

P-stranding, ellipsis: acceptable | |||||

B′: | Mijn | favoriete | film. | ||

my | favorite | film | |||

(32) | A: | WaarR | kijkt | hij | naar? | ||

where | looks | he | at | ||||

‘What is he looking at?’ | |||||||

P-pied-piped, non-ellipsis/cleft : unacceptable | |||||||

B: | Naar | mijn | favoriete | film | is | het. | |

at | my | favorite | film | is | it | ||

‘It is at my favorite film.’ | |||||||

P-stranding, non-ellipsis/cleft : unacceptable | |||||||

B′: | Mijn | favoriete | film | is | het. | ||

my | favorite | film | is | it | |||

‘It is my favorite film.’ | |||||||

The average results for this experiment are presented in Fig. 3. Notice that the results are significant for both the P-stranding and the P-pied-piping conditions. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test indicated that the +ellipsis ranks (Mdn = 7) are significantly higher than the −ellipsis (cleft) ranks (Mdn = 2) in the P-stranding condition; V = 3474.5, p < .001. Similarly, the +ellipsis ranks (Mdn = 7) are significantly higher than the −ellipsis (cleft) ranks (Mdn = 1) in the P-pied-piping condition; V = 4005, p < .001.

Based on these results, we conclude that P-less lexical remnants in Dutch do not originate as pivots of a cleft. We propose that these remnants are left-peripheral dislocated constituents that are resumed by an R-pronoun, with clausal ellipsis applying to the resumptive element and whatever follows it (33). This proposal is motivated by the fact that clausal ellipsis in (contrastive) left-dislocation is already known to be available in mainland Germanic languages in some contexts (Den Dikken and Surányi 2017; Abels 2018), and by the fact that there are independent reasons to assume that the non-elliptical counterpart of (31B′) involves (contrastive) left-dislocation with ellipsis of the demonstrative pronoun, as in (34).Footnote 6

(33) | Mijn | favoriete | film, | [ |

|

|

|

my | favorite | film | there | looks | he | at | |

‘My favorite film, (that’s) what he’s looking at.’ | |||||||

(34) | Mijn | favoriete | film, |

| kijkt | hij | naar. |

my | favorite | film | there | looks | he | at | |

‘My favorite film, (that’s) what he’s looking at.’ | |||||||

To summarize: in addition to confirming the claims made in the prior literature about preposition stranding under sluicing in Dutch, the results of our acceptability judgment experiments show that neither pied-piped PP remnants of sluicing nor ‘bare’ lexical DP remnants (i.e., DPs that are interpreted as complements of prepositions) are extracted from elliptical truncated or full clefts. From this, one may infer that any explanation for why bare R-pronoun remnants are disallowed under sluicing that appeals to non-isomorphic elliptical clefts is likely to be on the wrong track. In the case of ‘bare’ lexical DP remnants, we proposed that these are left-dislocated phrases in elliptical clauses that contain preposition stranding A′-movement, and which therefore do not violate Merchant’s preposition stranding generalization.

In short, our experiments confirm the generalization that Dutch R-pronouns cannot strand a preposition in an ellipsis site. In the next section, we refute the extant explanations for why this generalization holds.

3 Previous analyses

3.1 Merchant (2001): accentuating the R-pronoun remnant

Merchant (2001, 95) offers a prosodic explanation for the unavailability of preposition stranding under sluicing in R-pronoun contexts. He proposes that remnants of sluicing must be able to bear both non-contrastive and contrastive focal accents and that R-pronouns make for unsuitable remnants because they can bear only a contrastive focal accent (compare (35a) and (36); see also examples in Hoeksema 2014, 33). Thus, the unavailability of bare R-pronoun remnants in sluicing arises from a clash in the prosodic requirements of R-pronouns, which reject a non-contrastive accent, and sluicing, which induces such an accent (35b).Footnote 7

(35) | Non-contrastive (nuclear) accent on R-pronoun | |||||||||

a. | * | Ik | weet | niet | waarR | hij | op | rekent. | ||

I | know | not | where | he | on | counts | ||||

‘I don't know what he counts on.’ | (judgment from Merchant 2001, 95) | |||||||||

b. | * | Ik | weet | niet | waarR |

|

|

| ||

I | know | not | where | he | on | counts | ||||

‘I don't know what.’ | ||||||||||

(36) | Contrastive (nuclear) accent on R-pronoun | ||||||||||||||

Het | maakt | me | niet | uit | waarR | je | naar | kijkt, | als | je | maar | ergensR | naar | kijkt. | |

it | makes | me | not | out | where | you | at | look | if | you | but | somewhere | at | look | |

‘I don’t care what you look at, as long as you look at something.’ | |||||||||||||||

Merchant’s explanation only works if it is indeed true that R-pronouns cannot bear non-contrastive stress. Problematically, this assumption is false. The pitch contours of some of the pilot recordings we elicited from 3 Dutch native speakers show that R-pronouns can receive both contrastive and non-contrastive (i.e., nuclear/sentence-level) accent. This is shown on the pitch track in Fig. 4, which we generated from one of our pilot recordings.

(37) | Example used in Fig. 4 | |||||||||||

Hij | trekt | ergensR | aan, | maar | ik | weet | niet | waarR | hij | aan | trekt. | |

he | pull | somewhere | to, | but | I | know | not | where | he | to | pull | |

‘He is pulling something, but I don’t know what he is pulling.’ | ||||||||||||

As the arrow indicates, the F0 contour on the area where the second R-pronoun (waar) is positioned exhibits a peak, which is the marker of an accent in Dutch. The area that follows this peak bears a low level flat F0, indicating that this area (i.e., the string hij aan trekt) is deaccented and that the accent on the R-pronoun is the last accent in the sentence. The contrast between the accented R-pronoun and the succeeding deaccented area is also reflected in the mean F0. The mean F0 of waar is 210 Hz, whereas the mean F0 of the deaccented area that follows waar is 165 Hz. Since the final accent in Dutch is interpreted as the most prominent one, it is analyzed as bearing the nuclear/sentence-level accent (Gussenhoven 1984). From this pitch track, we can therefore conclude that the R-pronoun does bear a non-contrastive accent, and this accent is a sentence-level nuclear accent.

Considering that R-pronouns may indeed bear (non-)contrastive accents, Merchant’s analysis cannot be correct: there must be another reason for why R-pronouns that bear a non-contrastive accent (such as (35b)) or a contrastive one (such as (38), which is the elliptical counterpart of (36)), cannot be remnants of sluicing.

(38) | * | Hij | trekt | ergensR | aan, | maar | ik | weet | niet | waarR |

|

|

|

he | pulls | somewhere | to, | but | I | know | not | where | he | to | pulls | ||

‘He is pulling something, but I don't know what.’ | |||||||||||||

3.2 Accenting the elided preposition

Another potential prosodic solution rests on the assumption—which we will adopt in this subsection for the sake of argument—that ellipsis involves radical deaccentuation (Tancredi 1992). This refers to the idea that only material that is already given (in Schwarzschild’s 1999 sense) and therefore prosodically deaccented can be rendered unpronounced:

(39) | Radical deaccentuation cannot target items that must be accented. |

Equipped with (39), one may propose that preposition stranding under sluicing is banned in Dutch because the preposition that is left behind in the ellipsis site must bear an accent, which precludes radical deaccentuation (i.e., ellipsis).

At first glance, this explanation seems plausible, as prepositions do indeed receive an accent in most R-pronominalization configurations (see (40), and also Merchant 2001; Gussenhoven 1984, 178−179).

(40) | a. | Waarvan | heb | je | genoeg? | |

where.of | have | you | enough | |||

‘What have you had enough of?’ | ||||||

b. | Waar | krabde | je | het | vanaf? | |

where | scratch | you | it | of.from | ||

‘What did you scratch it off from?’ | ||||||

For this analysis to work, prepositions in R-pronominalization configurations must always bear an accent. Problematically, this is not true. The example in (41) and its accompanying pitch track in Fig. 5 show that such prepositions can indeed be deaccented.

(41) | Bob | schrijft | ergens | over, | maar | ik | weet | niet | waar | hij | over | schrijft. |

Bob | writes | somewhere | about | but | I | know | not | where | he | about | writes | |

‘Bob is writing about something, but I don’t know what he is writing about.’ | ||||||||||||

Like the contour in Fig. 4, the F0 contour in Fig. 5 exhibits a peak on the area where the R-pronoun waar is positioned in the second clause. This marks the nuclear, sentence-level accent. The area that follows this peak bears a low level flat F0, indicating that this area (i.e., the string hij over schrijft) is deaccented and that the accent on the R-pronoun is the last high pitch accent in this sentence. Just like in Fig. 4, the mean F0 of the accented R-pronoun is higher than the mean F0 of the succeeding deaccented string. The mean F0 of waar in Fig. 5 is 235 Hz, whereas the mean F0 of the deaccented area that follows waar is 172 Hz. As the contour below the arrow indicates, the preposition over is deaccented, bearing a mean F0 of 158 Hz.

Furthermore, there are R-prominalization contexts in which prepositions clearly cannot be accented. This is seen in the examples in (42), in which the item that precedes the preposition, rather than the preposition itself, must be accented (see Gussenhoven 1984, 178 for discussion of related facts).

(42) | a. | Waar | heb | je | {genoeg | van / * | genoeg | van}? |

where | have | you | enough | of | enough | of | ||

‘What have you had enough of?’ | ||||||||

b. | Hier | is | ze | {blij | mee / * | blij | mee}. | |

here | is | she | happy | with | happy | with | ||

‘She is happy about this.’ | ||||||||

The fact that the prepositions in non-elliptical R-pronominalization configurations may be deaccented means that they can also undergo radical deaccentuation in elliptical contexts. Therefore, the unacceptability of a sluicing construction such as (43), which is the elliptical version of (41), cannot be related to the unavailability of radical deaccentuation on such prepositions.

(43) | * Bob | schrijft | ergens | over, | maar | ik | weet | niet | waar |

| ||

Bob | writes | somewhere | about | but | I | know | not | where | he | about | writes | |

‘Bob is writing about something, but I don’t know what he is writing about.’ | ||||||||||||

In summary, we conclude that neither the R-pronoun nor the preposition exhibit prosodic properties that prevent sluicing from occurring. Therefore, the ban on preposition stranding under sluicing in Dutch cannot be explained by appealing to the accentuation profile of either the preposition with the ellipsis site or the R-pronoun remnant.

3.3 Kluck (2015): overtness of P as a syntactic requirement

Recall the generalization on preposition stranding under sluicing presented in Sect. 2 [repeated below in (44)].

(44) | Dutch R-pronouns cannot strand a preposition in an ellipsis site. |

Kluck (2015) views ‘Merchant’s Wrinkle’ being related to prepositions rather than to preposition stranding. As a result, she recasts the generalization in (44) as follows:

(45) | Prepositions that select R-pronoun arguments must be overt in sluicing. |

Kluck suggests that R-pronouns are inherently semantically underspecified and interpreted as either a true locative or as an argument of a preposition only through a syntactic licensing process. She claims that a ‘locative-looking’ expression such as waar can only be interpreted as an argument of a preposition if its selecting preposition is overt. When there is no selecting preposition in the syntactic phrase marker, or when the selecting preposition is not overt, then only the locative interpretation is licensable, and therefore only the locative interpretation is obtained. The licensing conditions for both interpretations are schematized in (46). In the examples below, dotted arrows mark syntactic licensing.

(46) | a. |

| → | incompatible with the ellipsis of POVERT |

b. |

| → | compatible with the ellipsis of PNULL |

Kluck’s syntactic licensing mechanism correctly predicts that a sluicing remnant such as waar cannot be interpreted as the argument of a stranded preposition because the stranded preposition, having been rendered null by ellipsis, cannot license its R-pronoun argument. Thus, in a sentence such as (47), the copy of waar in the ellipsis site cannot be licensed by the elided preposition (assuming that the presence of an overt argument licensing preposition in the antecedent clause cannot serve as a licensor itself, via structural parallelism of some sort).

(47) | Pnull: | ✗ argumental licensing | ||||||||

* Hij | rekent | ergens | op, | maar | ik | weet | niet | |||

he | counts | somewhere | on | but | I | know | not | |||

[CP waarR |

| |||||||||

where | ||||||||||

‘He counts on something, but I don’t know what (he counts on).’ | ||||||||||

The only licensing configuration that suits sluicing contexts is (46b), in which the locative interpretation is licensed. Precisely how a null/elided preposition licenses the locative interpretation in Kluck’s account is illustrated in (48), in which the context allows for a (sprouted) true locative interpretation of waar.

Although the syntactic licensing conditions in (46) account for the ban on preposition stranding under sluicing in Dutch R-pronominalization contexts, this analysis exhibits several shortcomings.

First, the postulation of a syntactic licensing relation based on the phonological properties of its licensing head (i.e., overt or null) is ad-hoc, unattested elsewhere in the grammar of Dutch and involves ‘look-ahead’, as the syntactic licensing of the R-pronoun should take place earlier in the derivational procedure than ellipsis (according to every account that treats the process of deletion as a PF phenomenon). This holds for the licensing of argumental R-pronouns and locative R-pronouns alike.

Second, Kluck’s proposal wrongly predicts that whenever the licensor preposition is not overt (e.g., whenever it is elided), the argument meaning of the R-pronoun cannot be licensed, regardless of whether the R-pronoun itself is elided. This prediction is not borne out. In (49), for example, the elided R-pronoun ergens can receive an argumental interpretation despite its licensor preposition being null.

Third, since the licensing conditions in (46) are syntactic/semantic in nature, one expects to see similar effects in other languages that strand argument-licensing prepositions. English is a language in which such configurations can be found and in which, in some contexts, the extracted complement of a preposition can take the form of a locative adjunct. Consider the examples in (50) and (51), in which the remnant of sluicing where is in principle ambiguous between a locative and an argumental interpretation (see Caponigro and Pearl 2009 for an account of this ambiguity). Nevertheless, for both British English and American English speakers, the argumental reading is available for where the elliptical questions, and this reading is preferred over the locative reading. The fact that the argumental interpretation is available under ellipsis, even when the licensor preposition is null, shows that the licensing conditions in (46) do not apply in a closely-related language, which in turn casts doubt on their reality in Dutch.

(50) | A: You have to fly through a lot of places on your way to Vancouver. | |

B: Where exactly? | ✓argumental = Wherei exactly | |

(51) | A: I have taken ideas from a lot of articles. | |

B: Where exactly? | ✓argumental = Wherei exactly | |

Because of these shortcomings in Kluck’s proposal, we believe the explanation for ‘Merchant’s Wrinkle’ should be sought elsewhere. We present our own proposal in the next section.

4 A novel analysis: ‘Merchant’s Wrinkle’ as EPP repair

4.1 An informal overview

Several researchers have argued that ellipsis bleeds overt A-movement of the subject to SpecTP. Merchant’s (2001) evidence for this comes from the observation that the Subject Condition (Chomsky 1973) seemingly ceases to apply under sluicing in English [compare the examples in (52)]. Assuming that subjects are islands in non-elliptical contexts because they occupy a derived position (i.e., they are A-moved phrases) (53a), Merchant proposes that subjects inside ellipsis sites are not islands because they do not occupy a derived position. Instead, their movement to SpecTP is bled, meaning that they occupy their base position (53b). Put differently, Merchant proposes that the Subject Condition still applies under sluicing but is circumvented by A-movement being bled.

(52) | a. | * | [Which Marx brother]1 is [a biography of t1] going to be published this year? |

b. | A biography of a Marx brother is going to be published this year, guess which one! |

(53) | a. | For (52a): [which MB]1 … [TP [a biography of t1]2 [vP t2 … ]] |

b. | For the ellipsis site in (52b): [which one]1

[ |

Van Craenenbroeck and Den Dikken (2006, 658) use the same reasoning to explain why the elliptical clause in (54b) is acceptable whereas its non-elliptical counterpart in (54a) is not, following a proposal in Den Dikken et al. (2000). In (54a), the NPI subject cannot be licensed because negation does not c-command it, whereas in (54b) the NPI subject is licensed because it remains in its base position, from which negation c-commands it, as (54c) shows. Note that the representation in (54c) reflects the so-called in-situ view of ellipsis, an operation that does not utilize movement of the remnant to allow unselective deletion of a syntactic constituent.

(54) | a. | * | Any of the printing equipment didn’t work. | |

b. | A: | What didn’t work? | ||

B: | Any of the printing equipment. | |||

c. | For the ellipsis site in (54a):

[ | |||

Van Craenenbroeck and Den Dikken (2006, 658−663) also argue that movement to SpecTP is bled in Dutch elliptical constructions. Their evidence comes from how complementizer agreement and sluicing interact in Dutch dialects. First, they observe that complementizer agreement is possible in certain varieties of Dutch, but only when the subject has moved to SpecTP (i.e., above the adverb allichte ‘probably’):

(55) | a. | … | darr-e | wiej | allichte | de | wedstrijd | winne | zölt. | Hellendoorn Dutch |

that-agr | we | probably | the | game | win | will | ||||

b. | … | darr(*-e) | allichte | wiej | de | wedstrijd | winne | zölt. | ||

that-agr | probably | we | the | game | win | will | ||||

‘… that we will probably win the game.’ | ||||||||||

Second, they observe that complementizer agreement is not permitted under sluicing (compare the examples in (56)). This, they claim, is expected if subject-movement to SpecTP is bled under ellipsis: the ellipsis site will always pattern with (56b), in which the absence of subject-movement blocks complementizer agreement.

(56) | a. | Jan | weet | niet | wie | darr-e | wiej | gezien | hebt. | Hellendoorn Dutch | |

Jan | knows | not | who | that-agr | we | seen | have | ||||

‘Jan doesn’t know who we have seen.’ | |||||||||||

b. | Wiej | hebt | ’r | ene | ezeen, | en | Jan | weet | niet | wie(*-e). | |

we | have | there | someone | seen | and | Jan | knows | not | who-agr | ||

As is well known, subject-movement to SpecTP in English occurs to satisfy the Extended Projection Principle (the EPP; Chomsky 1981), which states that the structural subject position—i.e., SpecTP—must be filled. The EPP is a formal syntactic requirement, insofar as it has no intrinsic semantic motivation. Chomsky (1995) recasts the EPP as the description of a syntactic feature, namely the uninterpretable D feature that resides on T. This feature is strong, which means that, when it Agrees with the closest phrase that satisfies it, it triggers overt movement to T’s specifier (ibid.). This movement can therefore be viewed as EPP-driven movement. Adopting these ideas, Merchant (2001) characterizes the bleeding of subject-movement to SpecTP under ellipsis as the bleeding of EPP-driven movement. Exactly how ellipsis bleeds EPP-driven movement is currently unknown, as no adequate formal analysis has yet been developed that avoids the ‘look-ahead’ problem that afflicts Merchant’s (2001) original account (though see Den Dikken 2013 for possible workarounds). We do not attempt to develop such an analysis here: we instead assume that such an analysis can in principle be developed (i.e., the task might be difficult, but not impossible). What is important for our current purpose is not how ellipsis bleeds EPP-driven movement but simply that ellipsis does bleed it, and that there is robust empirical evidence for this fact. Consequently, the generalization presented in (57) will suffice for our purposes.Footnote 8

(57) | Bleeding EPP-driven movement under sluicing |

Let F be a feature borne by a strong head. If F is a purely formal feature (i.e., it has no semantic import), then F is never present in a TP-ellipsis site.Footnote 9 |

In more recent research, the term ‘EPP-feature’ has been applied to other features that, like the uninterpretable D feature on T, are strong and which make no discernible semantic contribution. For instance, Cable (2010) characterizes the uninterpretable Q feature on C as an EPP-feature.

Our analysis of ‘Merchant’s Wrinkle’ capitalizes on the fact that EPP-features have been identified in additional syntactic domains. Extending the analysis in Koopman (2000), we propose that the head of the highest functional projection in the Dutch locative PP, namely PlaceP (which was referred to simply as ‘FP’ in Sect. 2), bears an EPP-feature, and it is this feature which, when checked by an R-pronoun, triggers movement of the R-pronoun to SpecPlaceP. If ellipsis bleeds EPP-features, then this feature should therefore be bled under sluicing. We propose that this is precisely what happens. Because SpecPlaceP is the ‘escape hatch’ through which R-pronouns must move in order to exit the PP domain to form P-stranding configurations such as P-stranding wh-clauses (see Sect. 4.2), bleeding EPP-driven movement of R-pronouns to SpecPlaceP therefore precludes R-pronouns from undergoing the wh-movement required to form wh-clauses. Put differently and more succinctly, we claim that:

(58) | A bleeding analysis of ‘Merchant’s Wrinkle’ |

P-stranding under sluicing in Dutch is impossible because ellipsis bleeds P-stranding wh-movement.Footnote 10 |

The rest of this section is devoted to positioning the proposal encapsulated in (58) within a formal syntactic theory of Dutch locative PPs, R-pronouns, and EPP-features (Sect. 4.2.1−4.2.2). Although we do this primarily to show that (58) is compatible with contemporary views on the syntax of Dutch PPs, we hope that presenting an explicit formalism for (58) will prove beneficial for researchers who are working on these or closely related phenomena in the mainland Germanic languages. We should mention at this point that we view the following analysis as only one possible treatment of the facts, and as such we are not especially wedded to the technical apparatus (e.g., systems of feature-checking, particular feature values, etc.) that we employ, despite the ease with which it captures the data at hand.

In addition to introducing such a formal theory, in Sect. 4.2.3. we will also show that our proposal of EPP satisfaction by R-pronouns finds parallels in the clausal domain as well, when considering recent work by Wesseling (2018) showing that both true pleonastics (er) and contentful locative phrases (such as hier ‘here’ and daar ‘there’) can satisfy T’s EPP feature.

4.2 The formal implementation

4.2.1 The technical apparatus: Pesetsky and Torrego’s (2007) feature system

We adopt the feature-sharing Agree system outlined by Pesetsky and Torrego (2007), who distinguish between the interpretability and valuation of features. This yields the fourfold typology presented in (59). Here, the symbols i and u stand for ‘interpretable’ and ‘uninterpretable’. The term that precedes the colon, which is represented here by the placeholder F, is the feature’s attribute, and the term that follows the colon, which is represented here by the placeholder val, is the feature’s value. An underscore denotes an unvalued feature. (When the interpretability and/or value of a feature is irrelevant to our analysis, we will not represent it in our phrase marker diagrams.)

(59) | iF: val | = | interpretable and valued |

iF: _ | = | interpretable and unvalued | |

uF: val | = | uninterpretable and valued | |

uF: _ | = | uninterpretable and unvalued |

In this system, the operation Agree (Chomsky 2000, 2001) works as follows:

(60) | Agree (simplified from Pesetsky and Torrego 2007) | |

a. | An unvalued feature Fα (a Probe) on a head H scans its c-command domain for another instance of Fβ (a Goal) with which to agree. | |

b. | Replace Fα with Fβ, so that the same feature is present in both locations. | |

We also assume that atomic features form feature-sets. For instance, the atomic features plural, gender, animate, etc., form the φ-feature feature-set (Harley and Ritter 2002).

We must make one extension to this otherwise well-established system of feature-checking. We will allow that feature attributes can, under well-defined conditions, be repurposed as values (61). This notion of repurposing feature attributes as values will play a pivotal role in the analysis presented below.

(61) | Feature repurposing |

If an Agree relationship has been established between Fα (the Probe) on head H1 and Fβ (the Goal) on head H2, then an independent feature attribute G on H1 can be repurposed as a value for Fβ (provided that G could independently serve as a value for Fβ). |

To provide an example of how (60) and (61) work together, consider the abstract scenario presented in (62). Because the φ-feature on H is unvalued, it probes its c-command domain for another occurrence of itself. It establishes an Agree relationship with the φ-feature bundle on X, and therefore receives val1 and val2 from its Goal. Problematically, one of the atomic φ-features on X (namely, F3) remains unvalued. When this happens, feature repurposing occurs, and G on H is repurposed as a value for F3.Footnote 11

In Sect. 4.2.2, we will present our assumptions regarding the internal syntax of R-pronouns. Afterwards, we will show how the internal syntax we assume interacts with the PP domain in which such pronouns are observed. Following a detailed formalization of how R-pronouns are derived in the domain of PP, we will revisit the elliptical cases. In line with (58), we show how the syntax we suggest for R-pronoun containing PPs are not fit for deriving whR (without an overt P) in the context of ellipsis.

4.2.2 The formal analysis

As already discussed in Sects. 2 and 3, Dutch has two types of locative pronouns: ‘true’ locative pronouns, which linearly follow their selecting preposition and which are interpreted as denoting a location, and R-pronouns, which linearly precede their selecting preposition and which, despite appearances, exhibit the syntactic and semantic hallmarks of standard, non-human personal pronouns (it, what, etc.). Kayne (2004) accounts for these differences by proposing that the pronounced item in each case (i.e., er, waar, daar, etc.) is not actually a pronoun but rather a demonstrative that selects for a null noun, either place (in the case of true locatives) or thing (in the case of R-pronouns) (63).Footnote 12/Footnote 13

(63) | True locative pronoun | R-pronoun |

|

|

For reasons discussed later in this subsection, we believe that Kayne’s core insight is better served by adopting a decompositional, Distributed Morphology approach, in which waar, er, daar etc. is the phonological realization of a complex syntactic head comprising an underspecified n head and a D head that can be specified for definiteness and wh-features. In the ‘true locative’ case, n bears an interpretable loc feature, which captures the fact that true locatives arise with an inherently locative meaning (64). Although n in the R-pronoun case also bears loc, it does so only as a formal φ-feature value (65). A first-blush approximation of the Vocabulary Insertion rules for waar, er, daar, and hier are presented in (66). (Note that D and n must Fuse (Halle and Marantz 1993) before these Vocabulary Insertion rules apply.)

(66) | [+wh, +loc] | ⇔ | waar |

[+def, +prox, +loc] | ⇔ | daar/er | |

[+def, −prox, +loc] | ⇔ | hier |

Let us focus on the n head in (65). Following the standard assumption that n heads are subcategorized for certain inherent inflectional morphological values (i.e., they ordinarily bear φ-features for gender and animacy) (Don 2004; Aquaviva 2009; Kalin 2019), we propose that the inanimate feature value on n in Dutch is defective, insofar as it arises from the lexicon without a prespecified value. This feature must therefore be valued via an Agree relationship with a suitable c-commanding Probe (Chomsky 2000, 2001). Problematically, those prepositions with which R-pronouns appear do not bear suitable Probes for n’s defective feature, and, as a consequence, an uninterpretable φ-feature that can enter into an Agree relationship with n must be inserted on a higher functional head in the PP domain to ensure that the syntactic derivation can proceed without crashing. Put in Kalin’s (2019) terms, a functional head must, as a last resort, be converted into ‘φ-probe’ for n’s defective feature.

The functional head that establishes an agreement relationship with the R-pronoun is Place in Dutch (Koopman 2000; Den Dikken 2010), which c-commands the PP. We follow Koopman (2000) in analyzing Place as an attribute of those locative phrases that allow for R-pronominalization, but we do not adopt Koopman’s view that Place is the syntactic locus of locative meaning.Footnote 14 Due to its inherent relationship with location, we assume that Place has an unvalued uloc feature and it must establish an Agree relationship with the PP. In addition, Place is a strong head, which means that Agreeing with the PP will ordinarily trigger the overt movement of the PP to SpecPlaceP (67) (Koopman 2000). The fact that the PP moves to SpecPlaceP explains why a non-R-pronominal DP cannot strand its preposition in Dutch: P-stranding subextraction induces an island violation, as PP occupies a derived position.

As mentioned above, Place becomes a φ-probe in R-pronoun configurations. This means that Place will bear (at least) two features that will probe:

As (68) illustrates, Place must establish two distinct Agree relationships in R-pronoun configurations: one with the PP and one with the R-pronoun. Because Place is a strong head, one of these Agree relationships triggers overt movement of the Goal to SpecPlaceP. The word order of Dutch R-pronominalization, wherein an R-pronoun always precedes its selecting preposition (see Sect. 2), informs us that the R-pronoun, rather than the PP, always moves to SpecPlaceP (69).Footnote 15 Because Dutch does not permit multiply-filled specifiers (for instance, only one phrase can occupy the voorveld, which is usually analyzed as SpecCP; see the Taalportaal, section 11.1.III; Landsbergen et al. 2014), this entails that movement of the R-pronoun bleeds movement of the PP (Koopman 2000).

Because the φ-feature on Place is unvalued (by definition), it does not itself provide the defective−human feature on n with its much-needed value. Instead, an independent feature on Place is co-opted for this purpose, utilizing the operation of Feature Repurposing defined in (61) from Sect. 4.2.1. This feature will then be transferred to n via the established Agree relationship, where it will serve as the value for n’s defective−human feature. Because Place independently bears an uninterpretable loc feature, the value transferred to n is therefore loc, as (69) already shows. This is how R-pronouns receive their +loc specification and are consequently exponed in a locative form.

As the highest specifier in the functional sequence that comprises the PP domain, SpecPlaceP is the escape hatch from which an R-pronoun may escape the PP domain altogether, thus stranding its preposition inside the PP (Koopman 2000; Den Dikken 2010, following van Riemsdijk 1978) (70). Because SpecPlaceP is an escape hatch only for phrases that can independently stop and be spelled-out in its specifier (i.e., if movement to SpecPlaceP is triggered for reasons other than escaping the PP domain), PP-pied-piping configurations involve movement of the entire PP domain (ibid.), as already mentioned in Sect. 2, and as shown in (71) and (72).Footnote 16

(70) | R-pronoun leaves the PP domain; P is stranded | ||||

WaarR1 | kijkt | hij [PlaceP t1 … [PP | naar t1]]? | (repeated from (12)) | |

where | looks | he | at | ||

‘What is he looking at?’ | |||||

(71) | Standard PP-pied-piping | |||||||

[PlaceP | [PP | Naar | welk | boek]]1 | kijkt | hij | t1? | |

at | which | book | looks | he | ||||

‘Which book is he looking at?’ | ||||||||

(72) | P-pied-piping in R-pronominalization context | ||||

a. | WaarRnaar | kijkt | hij? | (repeated from (14)) | |

where.at | looks | he | |||

‘What is he looking at?’ | |||||

b. | [PlaceP WaarR1 … [PP naar t1]]2 kijkt hij t2? | ||||

Before returning to ellipsis, let us summarize the formal analysis of R-pronominalization that we have outlined so far. While we have adopted Kayne’s (2004) suggestion that the syntactic and semantic differences between true locative pronouns and R-pronouns can be attributed to them exhibiting distinct nominal cores, we have departed from Kayne’s analysis by couching this distinction in a ‘decompositional’ framework. We did this for two reasons. First, such an approach naturally explains why Dutch R-pronominalization is obligatory. If the phonological exponence of a non-human pronoun is determined by its syntactic environment (as we claim), then every such pronoun that is merged in the ‘R-pronoun’ position—i.e., a position from which it will receive the value loc under Agree with Place—will necessarily be realized in the locative form. In other words, it is impossible to expone the standard pronoun het/wat in this position, as the Vocabulary Insertion rule(s) for het/wat do(es) not include +loc. In contrast, Kayne’s account requires additional stipulations to capture the fact that R-pronominalization is mandatory, which Kayne himself neglects to provide.

Second, it explains why only pronouns, and not non-human lexical DPs, undergo movement to SpecPlaceP. This is because the n head that nominalizes a lexical root need not be specified for ±human features, as the (non-)humanness of roots is conventional knowledge and therefore not encoded in the grammatical system in Dutch. Because pronouns are functional items (and are therefore rootless by definition), their (non-)humanness does need to be expressed via a grammatical means, namely via φ-features on n.

We have also adopted Koopman’s (2000) claim that Place is a strong head and that the PP and R-pronoun compete to fill Place’s specifier (with the R-pronoun always winning). By adopting Koopman’s analysis, we inherit from her an explanation for why Dutch is ordinarily a non-P-stranding language (namely, PP occupies a derived position and is therefore an island for subextraction).

Let us now return to ellipsis, recalling from Sect. 4.1 the following generalization:

(73) | Bleeding EPP-driven movement under sluicing |

Let F be a feature borne by a strong head. If F is a purely formal feature (i.e., it has no semantic import), then F is never present in a TP-ellipsis site. |

In this subsection, we have seen that Place, a strong head, bears two features. Both of these features are uninterpretable: the uloc feature lacks semantic import (see footnote 14 above), and the φ-feature that is inserted purely as a last resort (to ensure that the R-pronoun’s −human feature is valued and therefore that a derivational ‘crash’ is avoided) is similarly uninterpretable. For this reason, both of these features fit the description in (73) of an EPP-feature, and therefore are never present in a TP-ellipsis site. As already mentioned in Sect. 4.1, the repercussion of this is that wh-R-pronouns do not undergo movement to SpecPlaceP under sluicing, and therefore cannot escape via this position to SpecCP (in addition to this, they fail to get a loc value for their defective i−human feature; see (74)). This bleeds preposition stranding wh-R-movement under sluicing. (Note that R-pronominalization is still available in the configuration exemplified in (75) because the entire PP domain escapes ellipsis, and therefore Place is not contained within the TP-ellipsis site.) Consequently, Dutch still conforms to the preposition stranding generalization, and therefore ‘Merchant’s Wrinkle’ is successfully ironed out.

Before closing this section, we must add that the core of our proposal, namely that ellipsis bleeds EPP-features in the manner defined in (57/73), should not be extended to the edge features that are needed to derive successive-cyclic movement in Chomsky’s (2008) system. We believe edge features should be excluded from the group of EPP-features proper (i.e., strong features) for the following reasons. First, there are weak counterparts of the strong features, with the variant observed being subject to cross-linguistic variation. The presence/absence of edge-features is not subject to cross-linguistic variation, however. Second, the movement driven by strong features is encapsulated: the moved item need not necessarily move further. Conversely, items moved by edge-features always move further, as edge-features attract items into intermediate positions in an A′-chain. Third, while EPP features proper satisfy a PF-demand, edge-features satisfy computational demands: they are only present in a derivation when needed to enforce successive-cyclic movement, unlike the strong features we are dealing with. For these reasons, we believe that strong features and edge-features do not form a natural class, and consequently there is no expectation that they should behave similarly under ellipsis.Footnote 17

4.2.3 A parallel in the clausal domain: EPP checking by er and true locative pronouns

Having introduced our analysis in the previous two subsections, we turn now to the broader picture, with the hope to convince the reader that the EPP-driven movement observed in the PP domain in Dutch (i.e., movement to SpecPlaceP) can be related to satisfying the EPP in the inflectional domain (i.e., filling SpecTP).

Recent research from Wesseling (2018) suggests that the two phenomena share important commonalities, namely that both Place and T come prespecified with a loc feature and both can be φ-probes. According to Wesseling, T also exhibits the property of requiring only one of its two features—either the loc or φ feature—to be checked under Agree (whether Place exhibits the same property is beyond the scope of this paper). This commonality explains why true pleonastic subjects in Dutch, such as those found in impersonal passive configurations (76), arise in the same locative form that some R-pronouns do, and for why semantically contentful locative phrases (such as hier ‘here’ and daar ‘there’) can satisfy the EPP. In the case where the EPP is satisfied by a semantically contentful locative pronoun, such pronouns are probed by T’s loc feature, rather than by its φ-probing feature (77). In the expletive case, the defective −human feature on n receives the loc value from the φ-probe on T [see (78)], and therefore the expletive is exponed as a locative, according to the Vocabulary Insertion rules listed in (66). Note that exponence of non-human pronouns as locatives is restricted to R-pronouns and pleonastic subjects because it is only in the structural configurations that these pronouns are observed that n’s defective feature will fail to procure a value from another φ-probe already in present in the syntax [such as under sisterhood with v, in the case of Agentive subjects (79)].

(76) | Ik | denk | dat | {er/ | daar/ | hier} | waarschijnlijk | wordt | gezongen. |

I | think | that | expl/ | there/ | here | probably | is | sung | |

‘I think that there is probably singing (there/here).’ | (modified from Wesseling 2018, 4) | ||||||||

The fact that locative features have been implicated in satisfying the classic EPP in Dutch provides indirect but independent support for our claim that movement of R-pronouns to SpecPlaceP is EPP-driven movement, which, like other EPP-driven movement investigated in the literature, is subject to bleeding under sluicing.

5 Extensions

In the previous section, we argued that ellipsis itself—rather than, e.g., the prosody requirements of the R-pronoun—is responsible for bleeding preposition stranding under sluicing in Dutch. If this is true, then preposition stranding is bled in all configurations that involve clausal ellipsis, not just sluicing. This can therefore be utilized as diagnostic for clausal ellipsis in more ‘exotic’ syntactic structures.

Let us first apply this diagnostic to right node raising, a configuration whose syntactic structure remains hotly debated (see Barros and Vicente 2011 for pertinent discussion and references). For advocates of ellipsis-based analyses of right node raising, an English right node raising utterance such as (80a) is derived via the application of clausal ellipsis in the initial coordinand (80b). If ellipsis-based analyses are correct, then stranding a preposition in the alleged ellipsis site in the initial coordinand should be impossible in Dutch R-pronominalization contexts, leading to the prediction that an R-pronoun should not arise unaccompanied by its preposition in the initial coordinand. The examples in (81) demonstrate that this prediction is not borne out: the relevant R-pronouns (daar in each case) can arise unaccompanied by their prepositions (over and naar, respectively). This suggests that, at least in cases such as these, right node raising is not derived via ellipsis—a conclusion that dovetails with the conclusions drawn by McCawley (1982), Wilder (1999), de Vos and Vicente (2005), Bachrach and Katzir (2009), and others.

(80) | a. | I think Bill, but John probably thinks Mary, is the best candidate for the job. |

b. | [&P [I think Bill |

(81) | a. | Ik | zal | misschien | daarR, | maar | in | elk | geval | niet | hierR, | over | willen | praten. |

I | will | perhaps | there | but | in | every | case | not | here | about | want. inf | talk. inf | ||

‘Perhaps that, but at any rate not this, I would like to talk about.’ | ||||||||||||||

b. | Ik | zal | misschien | daarR, | maar | in | elk | geval | niet | hierR, | naar | willen | kijken. | |

I | will | perhaps | there | but | in | every | case | not | here | about | want. inf | talk. inf | ||

‘Perhaps that, but at any rate not this, I would like to talk about.’ | ||||||||||||||

We can also apply our diagnostic to so-called reformulative appositions. These are appositions that function to provide an additional referent for their anchor (see (82a), where the apposition and its discourse markers are italicized, and anchor is boldfaced). The syntactic structure of (seemingly) subclausal reformulative appositions is debated: some researchers claim that they are derived by clausal ellipsis (82b) (Döring 2014; Ott 2016) whereas others argue that they are not (82c) (Griffiths 2015a, b). In the Dutch cases, one observes that reformulative appositional R-pronouns—daar in each example in (83)—can arise unaccompanied by a preposition. This would be impossible if the appositional R-pronoun was the remnant of clausal ellipsis, as ellipsis bleeds preposition stranding. This therefore suggests that reformulative appositions are not derived by clausal ellipsis, which aligns with Griffiths’ conclusions. More specifically, Griffiths argues that reformulative appositions are coordinated with their anchors, which yields the prediction that a reformulative apposition must have the same syntactic/semantic type as its anchor (as coordination must be balanced). The Dutch R-pronoun data provide support for this aspect of Griffiths’ analysis, too: a DP anchor cannot be followed by a PP apposition, and vice versa (84).

(82) | a. | The Big Apple, i.e. New York, is a huge city. |

b. | The Big Apple, i.e. New York | |

c. | [&P [DP The Big Apple], i.e. [DP New York]], is a big city. |

(83) | a. | ? | Hij | zit | ergensR, | misschien | wel | daarR, | naar | te | kijken. | |

he | sits | something | perhaps | aff | there | at | to | look. inf | ||||

‘He is looking at something, perhaps that.’ | ||||||||||||

b. | Hij | zit | ergensR | naar, | misschien | wel | daar R | naar, | te | kijken. | ||

he | sits | something | at | perhaps | aff | there | at | to | look. inf | |||

‘He is looking at something, perhaps at that.’ | ||||||||||||

(84) | a. | ?* | Hij | zit | ergensR, | misschien | wel | daar R | naar, | naar | te | kijken. |

he | sits | something | perhaps | aff | there | at | at | to | look. inf | |||

‘He is looking at something, perhaps at that.’ | ||||||||||||

b. | * | Hij | zit | ergensR | naar, | misschien | wel | daarR, | te | kijken. | ||

he | sits | something | at | perhaps | aff | there | to | look. inf | ||||

‘He is looking at something, perhaps that.’ | ||||||||||||

6 Conclusion

This paper offered an explanation for the observation that preposition stranding is bled under sluicing in Dutch R-pronominalization configurations—an observation that, at first glance, appears to contradict Merchant’s (2001) preposition stranding generalization. Having demonstrated that R-pronouns make for suitable remnants of sluicing (contra Merchant 2001) and that prepositions that select R-pronouns are elidable (contra Kluck 2015), we offered an analysis according to which ellipsis itself is responsible for preposition stranding being bled under ellipsis in R-pronominalization configurations. In particular, we adopted Koopman’s (2000) and Den Dikken’s (2010) claim that the initial step of syntactic movement that generates preposition stranding configurations in Dutch is EPP-driven and proposed that features that trigger EPP-driven movement are obligatorily absent in clausal ellipsis sites, which therefore precludes the preposition stranding under sluicing (following similar earlier proposals by Merchant 2001; Den Dikken and Van Craenenbroeck 2006; Den Dikken 2013). We presented a formal implementation of this idea, utilizing contemporary notions from Distributed Morphology and from Pesetsky and Torrego’s (2007) system of syntactic feature checking. The resulting analysis dovetails with recent research on the nature of the ‘classic’ EPP condition in Dutch from Wesseling (2018) and generates a diagnostic test that we utilized for diagnosing (the absence of) clausal ellipsis in right node raising and appositional configurations in Dutch.