Abstract

Purpose

To assess the influence of physician-selectable equipment variables on the potential radiation dose reductions during cardiac catheterization examinations using modern imaging equipment.

Materials

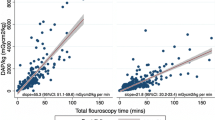

A modern bi-plane angiography unit with flat-panel image receptors was used. Patients were simulated with 15–30 cm of acrylic plastic. The variables studied were: patient thickness, fluoroscopy pulse rates, record mode frame rates, image receptor field-of-view (FoV), automatic dose control (ADC) mode, SID/SSD geometry setting, automatic collimation, automatic positioning, and others.

Results

Patient radiation doses double for every additional 3.5–4.5 cm of soft tissue. The dose is directly related to the imaging frame rate; a decrease from 30 pps to 15 pps reduces the dose by about 50%. The dose is related to [(FoV)−N] where 2.0 < N < 3.0. Suboptimal positioning of the patient can nearly double the dose. The ADC system provides three selections that can vary the radiation level by 50%. For pediatric studies (2–5 years old), the selection of equipment variables can result in entrance radiation doses that range between 6 and 60 cGy for diagnostic cases and between 15 and 140 cGy for interventional cases. For adult studies, the equipment variables can produce entrance radiation doses that range between 13 and 130 cGy for diagnostic cases and between 30 and 400 cGy for interventional cases.

Conclusions

Overall dose reductions of 70–90% can be achieved with pediatric patients and about 90% with adult patients solely through optimal selection of equipment variables.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Betsou S, Efstathopoulos EP, Katritsis D, et al. (1998) Patient radiation doses during cardiac catheterization procedures. Br J Radiol 71:634–639

Vano E, Gonzalez L, Ten JI, et al. (2001) Skin dose and dose-area product values for interventional cardiology procedures. Br J Radiol 74:48–55

Wagner LK, Archer BR, Cohen AM (2000) Management of patient skin dose in fluoroscopically guided interventional procedures. J Vasc Interv Radiol 11:25–33

Spahn M (2005) Flat detectors and their clinical applications. Eur Radiol 15:1934–1947

Holmes DR Jr, Laskey WK, Wondrow MA, et al. (2004) Flat-panel detectors in the cardiac catheterization laboratory: Revolution or evolution—what are the issues? Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 63:324–330

Hall EJ (2002) Lessons we have learned from our children: Cancer risks from diagnostic radiology. Pediatr Radiol 32:700–706

Bacher K, Bogaert E, Lapere R, et al. (2005) Patient-specific dose and radiation risk estimation in pediatric cardiac catheterization. Circulation 111:83–89

Shope TB (1996) Radiation-induced skin injuries from fluoroscopy. Radiographics 16:1195–1199

Koenig TR, Wolff D, Mettler FA, et al. (2001) Skin injuries from fluoroscopically guided procedures: Parts 1 and 2. AJR Am J Roentgenol 177:3–20

Lee CI, Haims AH, Monico EP, et al. (2004) Diagnostic CT scans: Assessment of patient, physician, and radiologist awareness of radiation dose and possible risks. Radiology 231:393–398

Gray JE, Swee RG (1982) The elimination of grids during intensified fluoroscopy and photofluoro spot imaging. Radiology 144:426–429

Drury P, Robinson A (1980) Fluoroscopy without the grid: A method of reducing the radiation dose. Br J Radiol 53:93–99

Onnasch DG, Schemm A, Kramer HH (2004) Optimization of radiographic parameters for paediatric cardiac angiography. Br J Radiol 77:479–487

Balter S, Gagney R (1998) A review of the influence of fluoroscopic geometry on patient dose. Scientific presentation at the 40th annual meeting of the American Association of Physicists in Medicine, San Antonio, Texas

Ogden K, Huda W, Scalzetti EM, et al. (2004) Patient size and X-ray transmission in body CT. Health Phys 86:397–405

Cusma JT, Bell MR, Wondrow MA, et al. (1999) Real-time measurement of radiation exposure to patients during diagnostic coronary angiography and percutaneous interventional procedures. J Am Coll Cardiol 33:427–435

Neofotistou V, Vano E, Padovani R, et al. (2003) Preliminary reference levels in interventional cardiology. Eur Radiol 13:2259–2263

Stern SH, Rosenstein M, Renaud L, et al. (1995) Handbook of selected tissue doses for fluoroscopic and cineangiographic examination of the coronary arteries. HHS Publication FDA 95-8288, Washington DC

McCollough CH, Schueler BA (2000) Calculation of effective dose. Med Phys 27:828–837

Leung KC, Martin CJ (1996) Effective doses for coronary angiography. Br J Radiol 69:426–431

Holmes DR Jr, Bove AA, Wondrow MA, et al. (1986) Video X-ray progressive scanning: New technique for decreasing X-ray exposure without decreasing image quality during cardiac catheterization. Mayo Clin Proc 61:321–326

Pooley RA, McKinney JM, Miller DA (2001) The AAPM/RSNA physics tutorial for residents: Digital fluoroscopy. Radiographics 21:521–534

Tsapaki V, Kottou S, Kollaros N, et al. (2004) Comparison of a conventional and a flat-panel digital system in interventional cardiology procedures. Br J Radiol 77:562–567

Rassow J, Schmaltz AA, Hentrich F, et al. (2000) Effective doses to patients from paediatric cardiac catheterization. Br J Radiol 73:172–183

Meier B (1997) Radiation exposure in the cardiac catheterization laboratory: An issue or a non-issue? Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 40:352

Schmidt PW, Dance DR, Skinner CL, et al. (2000) Conversion factors for the estimation of effective dose in paediatric cardiac angiography. Phys Med Biol 45:3095–3107

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nickoloff, E.L., Lu, Z.F., Dutta, A. et al. Influence of Flat-Panel Fluoroscopic Equipment Variables on Cardiac Radiation Doses. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 30, 169–176 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-006-0096-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-006-0096-6