Abstract

This study explored learners’ development and use of Opportunity to Learn (OTL) in the collaborative problem-solving context. We used commognitive approach to analyse interactions within student groups in a collaborative problem-solving math class. Two students who failed to use OTL and two groups they belonged to were selected for an in-depth exploration. We analysed the discourse used by and interaction made among these two groups to investigate how OTL develops from collaborative problem-solving and how students use them. The result shows that students who used less mathematical language and made fewer inter-personal interactions are hard to engage in the group discussion would miss OTL from collaborative problem-solving. Additionally, a mismatch in the discourse style with leader students in the group and a lack of interest in participation could also lead to students’ failure in seizing OTL in collaboration.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

5.1 Introduction

In the 1960s, American educational psychologist Carroll proposed the concept of Opportunity to Learn (OTL) which focuses on whether students can gain sufficient practice experience in their learning (Carroll, 1963). Since then, great efforts were paid to define what counts as OTL and study OTL as the unit of learning. Prior studies mostly concerned the classroom level and believed OTL results from teachers’ behaviour (Elliott & Bartlett, 2016). The assessment of OTL in PISA 2012 was also based on teachers’ instructions and support (OECD, 2014). Analysing OTL benefits teachers by improving their teaching practices (Stevens, 1993). In addition to teachers' support, OTL could appear from interactions among students. Through collaborative learning, students can learn by explaining their thinking, collectively reflecting on the solution, and learning from peers, which could be seen as OTL provided for students (DeJarnette, 2018).

Raising students’ ability to collaboratively solve problems is necessary in the context of the latest curricular reform, which implies the great value in studying how OTL develops and is used by students in this context. Firstly, the new curriculum emphasised that students should be the centre of classroom teaching while teachers provide guidance and support for their learning. Prior studies suggested the complex mechanism of students’ learning in the classroom (Langer-Osuna et al., 2020) and thus it is of great importance to study their classroom learning performance. Understanding how OTL develops and is used by students would maximise students’ self-learning. Secondly, one of the important aims of classroom learning is to gain the knowledge and develop the key competencies necessary to suit their further development in society. This aim has made studying how students gain and use OTL imperative for supporting students’ sustainable development. Finally, collaborative problem solving provides students with an open environment where they discuss the problem with each other to develop a solution on which everyone agrees through different phases (Salminen-Saari et al., 2021). Compared with traditional teacher-centred classroom teaching, collaborative problem-solving teaching allows students to express themselves more and thus would develop more OTL through student interactions.

This study investigated how OTL develops in the context of collaborative problem solving and how students use it. Firstly, we analysed the types of interactions students made and the discourse they used to figure out how OTL develops in collaborative problem-solving context. Two students failed to join in problem-solving tasks and their groups were analysed to figure out how they interacted with other group members how interactions could generate OTL and why they failed to seize the OTL developed from these interactions.

5.2 Literature Review

Since the concept of OTL was first proposed in the 1960s, scholars have tried to define it in different ways. Allwright divided OTL into three categories: opportunities to input, opportunities to exercise, and opportunities to manage (Allwright et al., 1991). This categorisation was accused to be oversimplified and it has been proposed that OTL should be divided into the opportunities to input, opportunities to output, opportunities to interact, opportunities to feedback, opportunities to practice repeatedly, opportunities to understand discourse, and opportunities to understand OTL (Mao, 2016).

Past studies have paid great attention to how students take advantage of OTL, how teachers could provide more OTL for students, and the assessment of OTL. A large proportion of studies of OTL in the classroom focus on OTL in online learning, the inequalities in OTL brought by racial or spatial differences, and the relationship between teachers’ attitudes towards teaching and students’ OTL. Additionally, several studies focus on the macro-level of students’ OTL (e.g., tuition fees, access to education) (Wang, 2018). While these studies have explored how external factors affect students’ OTL, less is known about how students themselves create and use OTL.

Studies evaluating OTL aim to delineate how teachers provide students with important learning resources. Scholars used different ways to assess OTL, such as discourse analysis, questionnaire, interview, classroom observation, and field notes. Reeves and colleagues used text analysis and classroom surveys to analyse African mathematics classroom videos. They evaluated the extent to which students accomplished classroom tasks to compare OTL use in mathematics classrooms in different countries (Reeves et al., 2013). Wang followed the OTL evaluation framework proposed by Stevens and designed a questionnaire that surveyed the content coverage, content exposure, teaching emphasis, and instructional delivery quality. Based on questionnaire results, he further analysed the relationship between students’ achievements and the OTL they received (Wang, 1998). Herman et al. (2000) developed an OTL evaluation framework consisting of four dimensions—classroom content, teaching strategies, teaching resources, and assessment—based on teacher and student questionnaires and interviews. Other domestic scholars evaluated OTL from ten dimensions (including aim, preparation, meaning, etc.) and found that secondary students could feel the opportunities in method and those in difference but found it difficult to feel opportunities in meaning and those in challenges (Yin, 2018). Hao used a questionnaire to study whether OTL appeared in classroom teaching equally (Hao & Hu, 2016).

OTL has been studied as a key variable predicting learning results. Goodlad proposed that it is necessary to consider OTL as an important variable if one links learning results and the OTL gained by them (Goodlad et al., 1979). Freud thought that differences in academic achievement could be seen as differences in OTL. Studies suggest that students’ academic achievement relates to OTL after controlling for students’ learning ability and socioeconomic status (Vernon, 1971). Similar studies suggest that OTL predicts students’ academic achievement more than teachers’ skills, teaching efficiency, and expectations.

Few domestic studies have studied OTL in Chinese classroom settings. Most studies, using data from large-scale international surveys like PISA, conclude that OTL may lead to differences in students’ learning achievement in different contexts. PISA surveyed students’ OTL in three dimensions: (1) learning formal mathematics; (2) learning textual mathematics problems; and (3) learning applied mathematics. A re-analysis of PISA 2021 data suggested that Chinese students’ mathematics performance is closely related to OTL, and that they had more opportunities to learn formal mathematics but fewer to learn applied and textual mathematics (Teng, 2014). Several researchers have analysed teacher-student interactions to study students’ OTL (Bai & Lin, 2016).

Other studies have found a weak association between OTL and secondary students’ academic performance but a stronger association between OTL and their non-academic achievements. They point out that self-learning plays an important role in learning, but students find it hard to get used to OTL provided by others. To sum up, the use of OTL is a possible learning result; thus, OTL is unequal to learning results. Additionally, while OTL use is closely related to students, it is also influenced by other factors like economics, resources, etc.

In the context of collaborative problem solving, OTL can influence students’ learning. Students can respond to others in the collaborative learning process, but whether they can understand each other is uncertain. However, most studies have focused on how teachers’ intervention can influence students’ OTL. This gap implies the necessity of understanding how students interact to attain and use OTL.

5.3 Theoretical Framework and Method

5.3.1 Commognitive Approach to Study Mathematics Learning

Commognitive approach was originated from a learning science stance that conceptualize learning as participationist rather than acquisitionist (Sfard, 2007). This approach conceptualise learning as a form of communication and thus suggests that learning can be achieved by revising and expanding one's discourse. In the commognitive approach, learning mathematics means “to individualise the historically established discourse known as mathematical” (Chan & Sfard, 2020). Here, “Individualise” refers to being the agentive participant of this discourse. Specifically, students can not only follow its rules but also transform it flexibly according to their will and use it to inform the next step. Highly individualised discourse would become the primary media for one's thinking. In this case, learning is conceptualised as one’s interactions with oneself. When it comes to case with more than one individual, learning is tantamount to conversations which have multiple channels and models not limited to verbal discussion. When two students are in a discussion, the discussion flow has three different channels (as shown in Fig. 5.1). There existed inter-personal channels where two individuals are interacting with each other. Intra-personal channels, however, allows interactions with oneself to promote both individuals' learning. Among these channels, only the inter-personal channel is observable, while the intra-personal is hidden from observers. This commognitive approach has been widely used in empirical studies examining collaborative learning because of its emphasis on the dynamic interactions in learning. In this study, we believe that OTL is developed from these two forms of interactions and three different channels among group members in the four-student groups’ discussions.

5.3.2 Opportunity to Learn (OTL)

Chan and Sfard (2020) generalised what kinds of interactions could count as OTL and in what circumstances OTL will develop. They suggested that there are two types of OTL, one of which is generated from a change in the initiative of students’ discourse. This change can give learners more opportunities to participate in interactions with mathematical discourse. This interaction, where learners talking about mathematical objects, could be called mathematizing. OTL will develop when learners interact and talk about mathematical objects or subjectify these objects. Here, subjectifying means students articultating their dispositions about mathematics. The development of the other type of OTL needs a change in the type of discourse itself rather than in the initiative of discourse. These OTL may appear in object-level or meta-level discourse or when learners meet problems that need to be verified. Additionally, to use these OTL, students must actively participate in group discussions by expressing themselves or listening to others’ explanations. These OTL could also be developed when students get in touch with language at different levels and have conflicts with others. The Table 5.1 generalises the two types of OTL and their characteristics.

5.3.3 Sampling and Data Collection

We used videos of collaborative problem solving in a secondary mathematics class in Beijing from the Social Essential of Learning (SEL) project. In this class, the collaborative problem-solving task was Taks A, “Xiaoming’s Apartment” (see Appendix for more details). A detailed investigation of interactions within the group is critical to understand how students can take advantage of OTL in collaborative learning activities. Rather than focusing on the successful learning cases, this study focused on students who failed to use OTL to reveal why students learn little in collaborative problem-solving. After carefully reviewing numerous collaborative problem-solving videos, two students and their groups were selected for further analysis to explore how OTL develops and benefits students through their interactions. Specifically, we found that some students got involved successfully initially but gradually got lost in the group discussion and further identified these groups for in-depth investigation. Each group included four students (two boys and two girls), coded separately as S1, S2, S3, and S4. Two characteristics were identified in these two groups:

-

(1)

Each student in the group spoke, so we could decide the role each played based on their discourse types.

-

(2)

In each group, one member was identified as a “focus student” who failed to participate in the group discussion actively. These focus students were marginalised because they did not pay sufficient attention to what other group members said or because other group members always reject their opinions.

5.3.4 Data Analysis

Videos were transcribed for further analysis. Firstly, to explore the discourse used in collaborative problem solving, we divided students’ discourse into two categories: mathematizing and subjectifying. There were two levels within the mathematical category: meta-level and object-level. The object-level concerns students' talking about mathematical objects while the meta-level concerns students' reflection on their talking about mathematical objects. Table 5.2 presents the coding scheme of students' discourse. We used different coloured circles with arrows to represent the type of discourse and direction of students’ interactions. As shown in Fig. 5.2, black circles refer to students’ discourse at the object level, meaning their discussions about mathematics itself. Grey circles refer to students’ discourse at the meta level, meaning their thoughts or comments on some mathematical objects. White circles refer to students’ discourse at the subject level, meaning their discussion about the learners themselves. Arrows show the types of interaction. Circles with arrows pointing to the bottom-left represent inter-person proactive interactions (students’ initiatively discussing with others), while those with arrows pointing to the upper-left represent inter-personal reactive interactions (students’ responding to others), and those with arrows pointing to the bottom represent intra-personal interactions (students’ talking to themselves). After trial coding and a refinement of the coding scheme, two researchers independently coded the data, attaining an 86% consistency rate.

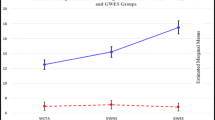

Additionally, we calculated the proportion of different types of discourse (Fig. 5.3) and the proportion of different types of interactions (Fig. 5.4). Considering there are four students within each group, we identified two different roles students are playing: leaders and followers. Leaders are charactersied with more mathematising discourse and more inter-personal interactions (e.g., S3 in the example). In this study, we focus on the interactions between focus students and leader students as such interactions could generate more OTL by getting focus students involved in collaborative learning. Although OTL appears in interactions indifferent forms and contents, we followed the definition by Chan and Sfard (2020) that captured OTL based on how discourse was developed and changed through students’ interactions.

After coding the discourse and determining each student’s role, we conducted a detailed analysis of the focus students’ discourse to determine how they interacted with other students and caught the OTL created from these interactions. The next section introduces each group’s collaborative problem-solving process and discusses the development of OTL. Figure 5.5 outlines the data analysis process in this study.

5.4 Results

5.4.1 Group 1

Group 1 had two boys and two girls. S2 was the focus student and participated less actively through the collaborative problem-solving process. At the beginning of the discussion, S2 interacted with others very well. As the discussion continued, however, S2’s opinions began to differ from other group members’, leading to conflicts. As a result, S2 missed several OTL generated from interactions among other group members, making it harder for him to follow later parts of the discussion.

5.4.1.1 The Stages of Discussion

We divided the collaborative problem-solving process into three stages based on S2’s performance and the group discussion content.

Stage 1: At this stage, group members mainly discussed the structure of the apartment and what one square metre looks like. However, S2 had vastly different opinions, and conflicts continually emerged. For example, when S4 proposed that the bathroom should be two square metres, S2 questioned her idea immediately, saying it was “impossible.” When S4 amended her idea and said, “five square metres should be enough,” S2 continued to reject it, declaring, “five square metres could never be enough.” From what S2 said, it was apparent that he wanted to join the group discussion by rejecting others’ views and gaining their attention. However, other students chose to ignore his rejections and went on with their original discussion. Finally, S2 stopped rejecting others (under the teacher’s guidance), and the group entered the next stage of discussion.

Stage 2: At this stage, group members discussed the overall arrangement of the apartment, including what rooms the apartment had and how to furnish them. S2 did not keep pace with the others in. While the group discussed how to divide the apartment into different rooms, S2 considered how to draw the apartment or proposed irrelevant requests. For example, when S2 wanted more pieces of white paper to draw on, S3 refused his request, saying, “You do not have to draw all the time.” Whenever S2 tried to start a topic, the others ignored or rejected him, leading to his failure to get involved in the group discussion.

Stage 3: At this stage, group members finished most of their prior discussions and started drawing the apartment’s arrangement on paper. S2 barely had any chance to participate in the discussion and instead just talked to himself. When other students decided to use a scale of 1:100, S2 said “it is irrational to use a scale of 1:1,” showing he had not paid attention to what the others had said. Later, when the group discussion focused on how to draw the kitchen, bathroom, and living room, S2 did not express an opinion; however, when the other members had almost finished the drawing, S2 began to question the result, again saying something like “this is impossible in real life.”

Overall, the focus student’s performance followed some patterns at different stages of the group discussion. The group discussion went on in an organised way. The group firstly focused on what an apartment should have (e.g., a kitchen, bathroom, and living room) and how large one square metre was, which was necessary preparation work for drawing the apartment’s floor plan. Then they moved to the overall arrangement of the apartment, the size of each room, and finally finished the task. At the beginning of the group discussion, the focus student kept questioning and explaining his ideas. But as the discussion continued, the focus student did not keep pace with others; instead, he thought about drawing (a task that should be done later) while his peers are discussing the arrangement. It is apparent that he wanted to take the initiative in the discussion but failed due to a mismatch between his ideas and those shared by the group. Finally, he lost interests and missed many of the ongoing discussion’s details, leading to a situation where he could only speak to himself.

5.4.1.2 Analysis of OTL

OTL developed in all three stages mentioned above through different types of discourse and interactions (see Table 5.3 for more details).

OTL in Stage 1: The first OTL appeared when the group was discussing the area of the bathroom. When S4 proposed that the bathroom could be two square metres, the focus student of this group (S2) questioned this idea, responding that it was “impossible.” In this interaction, their type of discourse transformed from the object level to the meta level with S2’s detailed explanation (“Because you need enough space to take a shower”). This explanation contributed to the development of the second OTL.

The third OTL was also developed while discussing the area of the bathroom. When S4 tried to adjust the bathroom to five square metres (“Actually, five square metres are enough”), S2 still rejected this new idea (“five square metres could never be enough”), which caused conflict between S2 and S4 again. In this conflicted interaction, the type of discourse transformed from the subject level to the meta level. The OTL did not work because S2 did not explain why he thought five square metres are not enough or suggest how many square metre should be enough.

The fourth OTL appeared from the discussion of the area of four bricks. When S3 suggested the area to be 36 square decimetres, S2 objected again, much as in the first OTL. The fifth OTL happened when the group was discussing the area of the bathroom under the teacher’s guidance. When the teacher checked on how Group 1 was progressing, S3 mentioned that they could not confirm the area of the bathroom. S2 followed S3’s question and asked, “How many square metres does a bathroom generally have?”, which produced OTL through questions.

It is noticeable that the conflicts between S2 and the other students were partly caused by the difference in the type of their discourse. More specifically, S2’s discourse was mostly at the meta level (e.g., “impossible”), while the students interacting with him turned the direction back to the object level. This could be seen as a latent conflict in the discourse structure.

OTL in Stage 2: The sixth OTL appeared when the group discussed the apartment's overall structure. S2 thought it better to draw their ideas on the paper first, while S3 disagreed (“We can discuss first and then draw on the paper…. You do not have to draw now”). At this time, conflicts appeared, and the discourse turned from the object level to the subjectifying level.

The seventh OTL appeared when discussing whether a bathroom should have a washing machine, as S3 suggested. S2 rejected this idea and sought to regain the interaction initiative (“Could you please listen to me first?”), moving the content of their interaction from the object level to the subjectifying level.

The eighth OTL happened when the group discussed the kitchen area. When the group discussed whether the kitchen area could be eight square metres, S2 did not pay full attention but questioned whether it should be smaller, directing the discussion content from the object level to the meta level.

The ninth OTL appeared while discussing the area of the bedroom, which S2 thought should be less than ten square metres, while others disagreed.

At this stage, S2’s discourse mainly aimed at returning to the group discussion by gaining the discourse initiative. However, his attempts did not always keep pace with the other members, leading them to ignore or disapprove of his ideas and causing his failure to participate in the group discussion. For example, when S2 said, “Could you please listen to me first?” S3 choose instead to discuss whether a bathroom should have a washing machine.

OTL in Stage 3: The tenth OTL appeared when choosing the scale. When S4 decided to use the scale of 1:100 (“We can use 1 cm to represent 1 m.”), S2 misheard the scale to be 1:1 and rejected S4’s idea again (“1:1 is impossible.”). It is apparent that S2 did not pay full attention to the others, leading to conflicts and turning the discourse type from the object level to the meta level.

The eleventh OTL emerged at the end of the discussion. When the group finished drawing, the focus student almost gave up on joining the discussion. S2 still made several criticisms (“This design is impossible”), but his ideas were again ignored.

Generally, the group’s discussion followed an organised order, proceeding from discussing the apartment’s overall structure to allocating the rooms and drawing the floor plan. However, the focus student consistently failed to follow the pace taken by the group. For example, the focus student wanted to draw when others discussed each room’s area. Additionally, the focus student’s ideas were always rejected or ignored, making him miss OTL.

5.4.2 Group 2

5.4.2.1 The Stages of Discussion

Based on the performance of S2 and the group discussion content, we divide the collaborative problem-solving process into three stages.

Stage 1: At this stage, the group focused on the general arrangement of the apartment and details about the kitchen and bedroom. In this process, S2 took a very active part in group discussion and tried to express his own ideas (e.g., “I think the living room should be here, and there should be three bedrooms next to the living room,” “I know what questions you have”). However, S2 did not get an active response from other students. For example, when S2 proposed the idea of three bedrooms, S3 rejected it immediately (“It is insane to have three bedrooms in 60-square-metres”).

The group spent a relatively long time discussing the area of the living room and the bedroom. When S2 proposed that he knew the key to solving the question, other students refused to give him the discourse initiative (“Could you stop talking?”). In the later discussion, S2 tried to express himself and actively join the discussion, but the other students seldom actively responded to him.

Stage 2: At this stage, the group had a general discussion on the area of each room. After repeatedly receiving negative feedback from other members, the focus student gradually lost enthusiasm for joining the group discussion. When the group had a heated debate about the area of specific rooms, S2 just echoed what others said and did not express his own ideas.

Stage 3: The main task in this stage was diagramming the apartment they had designed. S2 tried to rejoin the group discussion by initiating more interactions. When the group was discussing how to draw the graph, S2 proposed his ideas (“I think we can…,” “Listen to me, there is a simpler way that…”). However, the other students ignored him and discussed whether the bathroom and the toilet should be separate. When S2 asked, “Why do you split the bathroom and the toilet? They could be put together,” other members did not explain their thoughts and passed over this question (“He splits the two rooms, not me.”).

Although the focus student joined the group discussion more actively at this stage, he did not contribute any constructive ideas. In effect, the other students formed a “smaller sub-team” to continue their discussion, leading to S2’s missing many OTL that emerged from their interactions.

The focus students in the two groups had similar characteristics in the extent to which they actively participated in their group’s discussion. At the beginning of the group discussion, the focus student of Group 2 did not actively participate. It was apparent that he wanted to join the group learning at the second stage of discussion, but failed because he had paid little attention to other students’ ideas, leading them to ignore his. Even in the last stage, other students paid no attention to what the focus student said, which led to his missing many OTL.

5.4.2.2 Analysis of OTL

OTL developed in all of the above-mentioned three stages through different types of discourse and interactions (see Table 5.4 for more details).

OTL in Stage 1: OTL appeared four times in the first stage. The first OTL appeared during the discussion of the position of the living room and the bedroom. When the focus student proposed his idea (“I think the living room should be here and there are three bedrooms around the living room, you can put it”), other members rejected it, believing it was impossible to accommodate three bedrooms in a 60-square-metre apartment. Although he later tried to explain why there should be three bedrooms, the other students did not give him the chance, which made him lose this OTL. In this OTL, the type of discourse stayed at the object level.

The second OTL appeared in the discussion of the area of the apartment. The focus student suggested that he had found the key to solving the problem, but the others chose to ignore him. This negative response made it difficult for S2 to seize OTL. The type of discourse in this OTL moved from the object level to the subjectifying level.

The third OTL appeared when they were discussing the number of bedrooms. When S3 stated it was impossible to have three bedrooms in the apartment, the focus student questioned this (“Having three bedrooms could be possible.”); the other students did not follow their discussion. At this time, the type of discourse changed from the object level to the meta level.

The fourth OTL was in their discussion of how many floors an apartment should have. While the other students thought an apartment should have one or two floors, S2 thought one should have three or four. However, S2’s questioning was still ignored by the other members (“Could you stop talking for now?”), which led to his failure to seize this OTL.

OTL in Stage 2: The next three OTL emerged in the second stage. The fifth OTL appeared when the group discussed “whether a kitchen should have a door?” The focus student believed a kitchen does not need a door (“Why does a kitchen have to have a door?”), but the other group members said the “door” was simply the room’s exit (on the picture), not a real one. The type of discourse stayed at the object level in this discussion.

The sixth OTL appeared when the group discussed each room's area to calculate the apartment’s overall area. S4 thought the bathroom was similar to a half-circle and thus proposed calculating the area of a half-circle first. However, the focus student diverged from others and urged calculating the overall area based on the apartment structure rather than the area of each room. He refuted S4’s idea (“We could calculate the overall area by looking at the one enclosed by the edge. Why do we have to calculate each one?”). This mismatch led to the other students’ ignoring the focus student’s idea, following their shared one, and continuing to discuss the area of the bathroom. The type of discourse turned from the object level to the meta level.

The seventh OTL appeared when the focus student proposed an idea as the group discussed the area of the main bedroom (“The main bedroom should be at most half of the one you drew.”). This led the other group members to end this part of the discussion and start discussing the other four rooms. Their discourse type stayed at the object level.

OTL in Stage 3: The eighth OTL appeared while the group worked on the apartment floor plan. When the focus student tried to share his thoughts to initiate the discussion (“I had a simpler way to draw it that…”), the other members paid no attention and focused on discussing whether the bathroom and toilet should be placed together. The discourse type in this discussion turned from the object level to the subjectifying level.

The ninth OTL appeared when the group calculated the area of the bathroom. The focus student proposed his own calculation method (“We can directly calculate the area of this”) but was rejected by the other members (“It will not work”). The discourse type of this short discussion changed from the object level to the subjectifying level. Due to repeated negative feedback, the focus student gradually stopped sharing his ideas.

The focus student in this group had some specific characteristics. In the first stage, the focus student did not participate actively but still tried to join the others. However, the focus student failed to integrate into the group due to negative feedback, leading to an inactive participation. Although the focus student tried to rejoin the group in the third stage, he did not succeed until the end of the discussion.

5.5 Discussion

5.5.1 Type of Discourse

In the collaborative problem-solving process, the proportion of mathematizing discourse used by the focus student in Group 1 first increased then decreased later, while the proportion of his subjectifying language remained at a relatively high level. For the focus student of Group 2, the proportion of mathematizing discourse was low at first but increased later, while the proportion of his subjectifying discourse increased at first but decreased later.

The focus student of Group 1 actively participated in the group discussion in the first stage and constantly tried to initiate discussion in the second stage to get back to the group discussion. However, the other members rejected or ignored his ideas as he is not at the same page, leading to his decreased participation in the third stage. Therefore, while the focus student’s involvement was first active, this activeness decreased later, making him miss many OTL. We also found that the focus student in group 1 used mathematizing discourse more at the beginning of each discussion stage and subjectifying discourse more at the end of each satge.

The focus student of Group 2 was similar to the one of Group 1. Both actively participated in the group discussion in the some stages and tried to initiate the discussion, while the other students rejected their ideas. The difference lies in that Group 2 focus student did not actively join the discussion at the first beginning but tried to rejoin in later stages. The negative feedback from others in Group 2 made focus student failed to get involved in the second stage. In the third stage, the focus student tried to rejoin the group discussion and became more active. His inactive involvement in the first stage and failure to re-involve in later stages in the group discussion made him miss more OTL. Like his counterpart in Group 1, Group 2’s focus student used mathematizing discourse more at the beginning of each discussion stage and subjectifying discourse more at the end.

A detailed analysis of the discourse type suggests that the proportion of different types of discourses may influence students’ involvement in collaborative problem solving and further their use of OTL. More specifically, the more mathematizing discourse and less subjectifying discourse students used, the more active they were in the group discussion and the more OTL they could gain. On the contrary, if students use more subjectifying discourse and less mathematizing discourse, they might find it hard to join the group discussion and miss several OTL.

Table 5.6 and Table 5.7 compare the proportion of different types of discourse used by the leader student and focus student (who played the follower role) in each group. For Group 1, S2 was the focus student and follower, while S3 led the collaborative problem-solving process, using the largest proportion of mathematizing discourse in the group. As shown in Table 5.6, the follower student and leader student influenced the proportion of the two types of discourse each other used: when the leader student used less mathematizing discourse, the follower student may use more. The same pattern appeared in their use of subjectifying discourse. This pattern may suggest that a mismatch in the discourse types could contribute to a failure in getting involved in collaborative problem-solving.

For Group 2, S2 was the focus student and follower, while S4 was the leader of the collaborative problem-solving process. Table 5.6 shows that in the first two stages, the discourse used by the leader student and follower student also influenced each other. As the third stage lasted a rather long time, both used a large portion of mathematizing and subjectifying discourse; however, the leader student still used less subjectifying discourse. Since the goal of group collaboration is to solve a mathematics problem, a extremely large proportion of subjectifying discourse could distract the flow of group discussion.

Figure 5.6 shows the relationship between the students’ different roles in collaborative problem-solving and their use of discourse in different types. The research results suggest the following two conclusions:

-

(1)

The proportion of different types of discourse used by students may influence their involvement in the group discussion. Especially, students who used more mathematizing discourse could more actively collaborative with others in the solving math problems.

-

(2)

The leader student and follower student could influence the proportion of different types of discourse that each other used. When the leader student used more mathematizing (or subjectifying) discourse, the follower student may use less.

Several reasons for students’ failure in participation were recognised from this perspective. Firstly, rather than trying to use more mathematizing discourse, the focus student used more subjectifying discourse to express himself, making it harder for him to communicate with others. Secondly, the focus student did not pay sufficient attention to the discourse used by the leader student or other students but tried to distract them, which prevented him from seizing and using OTL.

5.5.2 Type of Interactions

The type of interactions also changed in different stages (for details, see Group 1 in Table 5.7 and Group 2 in Table 5.8). For the focus student in Group 1, the proportion of intra-personal interactions decreased first and increased later, while the proportion of inter-personal interactions increased first and decreased later. In the first stage, the focus student interacted with other group members less and with himself more. In the second and third stages, these intra-personal interactions became less frequent and inter-personal interactions more frequent.

For the focus student in Group 2, the proportion of intra-personal interactions increased first and decreased later, while the proportion of inter-personal decreased first and increased later. In the first and the last stages, the proportions of these two types of interaction were essentially the same, while the focus student interacted with himself more and with others less in the second stage.

These changes suggest that the type of interaction may influence how students become involved in collaborative problem solving and whether they can use OTL. More specifically, the more students interacted with others, the more active they were in the group discussion, and the more OTL they took advantage of. In contrast, the more students interacted with themselves, the less active they were in the group discussion and the more OTL they missed.

Tables 5.7 and 5.8 also compare the types of interactions by the leader student and focus student (a follower student) in Group 1 and Group 2. For Group 1, the proportion of proactive interactions S3 (the leader student) made continually increased, while S2 (the focus student and follower student) made more such interactions and less later. The frequency of S2’s and S3’s intra-personal interactions first increased and then decreased. Generally, the leader student made more inter-personal interactions (whether proactive or inactive), while the focus student made more intra-personal interactions. This could suggest that the leader student tended to interact with others, while the focus student (as the follower) tended to interact with himself.

For Group 2, the proportion of proactive interactions that S4 (the leader student) and S2 (the focus student and the follower student) made decreased first and increased later, while their proportions of inactive ones kept decreasing. S4 made more and more intra-personal interactions, while the frequency of these interactions S2 made increased first and decreased later. Similar to Group 1, the leader student interacted more with others while the focus student interacted more with himself.

Figure 5.7 shows the relationship between different roles in the group problem solving and the interaction type made by these students. The research results suggest the following two conclusions:

-

(1)

The interaction type can influence the extent to which students participate in the group discussion and further their success in seizing OTL. Although intra-personal interactions can help students think independently, more inter-personal interactions can help involve them in collaborative problem solving.

-

(2)

Students in different roles had different interaction type preferences. Leader students preferred interacting with others, while follower students preferred interacting with themselves.

Several reasons for students’ failure in participation were recognised from this perspective. Firstly, the focus students made less interactions with others but always communicated with themselves. This excluded them from the group discussions and prevented them from integrating themselves into the group discussion. Secondly, the focus students did not follow the type of interactions made by the leader student as well as other members. When the leader students discussed ideas with other members, the focus students interacted with themselves. When the leader students and other members thought independently and interacted with themselves, the focus students tried to interact with others. However, by this time, the inter-personal interactions had nearly ended, leading to the focus students’ keeping missing OTL.

5.5.3 OTL and the Role of Student

We identified the leader student, follower student (focus student), and other members in each collaborative problem-solving group. It is suggested that OTL development is closely related to leader students. In the collaborative work process, the follower students conflicted with the leader students by explaining, questioning, and taking the discussion initiative. While these conflicts can create OTL, the focus students missed the emerging OTL by being ignored and failed to participate in the group discussions. Figure 5.8 shows a more systematic representation of how students in different roles interacted to develop OTL. The analysis of discourse types and interaction types in the previous two sections suggests that the transformation between different discourse types and the new conversation contexts generated by the leader students could be the foundation for developing OTL. The follower students’ explanations, questions, initiations, and conflicts further developed OTL. Several mismatches between focus students and leader students were summarised below from the perspective of OTL:

-

(1)

The types of discourse used by the leader and focus students were always different. Specifically, when the leader students used mathematical language, the focus students used subject language.

-

(2)

The focus students did not have a strong enthusiasm to join the group discussions. The conflicts they had with the leader students were not due to a mismatch in discourse type; they were a result of their blind refusal to participate. No matter what the leader students said, the focus students tended to focus on their own ideas rather than understanding the ideas the group has arrived upon.

-

(3)

The focus students could not closely follow the pace of group discussion, which is usually controlled by leader students. For example, in Group 1, the group first discussed what an apartment should have and what one square metre was, then the overall structure of the apartment and the size of each room. Finally, they drew the plan of the apartment on paper. However, the follower student did not follow this shared.

5.5.4 A Summary of Factors that Influence the Development of OTL

This chapter presents a detailed discussion of the different discourse and interaction types among students in different group roles. Qualitative analysis suggests that students’ discourse and interactions are related to OTL in a complex way, not a simple linear manner. More specifically, using mathematizing discourse and making inter-personal interactions promoted the extent to which students participated in the group discussion.

The discourse and interactions were also closely related to the leader students, focus students (usually a follower student who failed to engage in collaborative work), and other group members. This complex interactive relationship suggests that many factors influence OTL development. In the collaborative work on solving mathematics problem, discourse and interaction types differentiate students’ roles in group discussions. Students who used more mathematizing discourse and made more proactive interactions were identified the leader students. We assume that these leader students are talking more about mathematics and communicating with others to promote the problem-solving. A change in the leader students’ discourse type could facilitate OTL development. However, the alignment between leader students and focus students decided whether this OTL could be created successfully and further influenced whether the focus students could benefit from it.

In other words, the leader students provided OTL by changing the discourse type or initiating new discourse. Later, the followers could question or challenge leader students to create conflicts, which could further develop OTL. The followers could also develop OTL alone by explaining their ideas to others or initiating a discussion. Therefore, overuse of subjectifying discourse and frequently interacting with themselves were two main reasons the focus students (follower students) failed to participate in the group discussion. Figure 5.9 shows how different factors can influence OTL in collaborative problem solving.

5.6 Conclusion and Implications

This study has explored the development of OTL in collaborative problem solving in a secondary mathematics class. Instead of paying a close attention to successful cases, we focused on two groups where there is a focus students who failed to engage in group work and further to seize the OTL. By analysing students’ discourse and interactions, we identified different roles students played and closely examined the interactions between leader students and focus students to study how OTL can be developed, seized, and used. We further conceptualised how these factors could influence the development and use of OTL as a supplement to the current theoretical conceptualisation of the mechanism of collaborative learning.

Results suggest that students’ discourse and interactions are closely related to OTL development, as they can influence the extent to which students actively participate in group discussions and further their learning results. This is aligned with the nature of collaborative learning as social interactions that are highlighted by past studies (Palincsar & Herrenkohl, 2002). Specially, we found that students with less mathematizing discourse, more subjectifying discourse, and more intra-personal interactions are hard to participate in collaboration and thus fail to take advantage of OTL. According to Smith and MacGregor (1992), peer discussion and peer tutoring are the most common forms of collaborative learning, which requires an in-depth involvement in interactions. Despite the social nature of collaborative learning, Laal and Ghodsi (2012) also emphasised the academic nature of collaborative learning. This aligns with our findings that students used less mathematizing discourse would fail in get involved in group discussion to learn from their peers.

This study has several practical implications for teachers in the teaching of collaborative problem solving. Collaborative problem-solving teaching provides an open atmosphere for students’ learning, one that allows them to communicate with each other freely and elaborate on their advantages. Recent studies have revealed multiple factors that may influence such socialization culture (Dong & Kang, 2022), for example. Students are the agents of this sociocultural learning, while teachers are facilitators who provide guidance for students' learning. However, as teachers do not assign each student a discussion role but let them take on different roles naturally, leader students may not realise their responsibility and thus may make other group members miss many OTL. Therefore, teachers could assign different group discussion roles to students so that they can discuss ideas in a more organised way and effectively use more OTL.

References

Allwright, R., Allwright, D., & Bailey, K. M. (1991). Focus on the language classroom: An introduction to classroom research for language teachers. Cambridge University Press.

Bai, Y., & Lin, Y. (2016). Conceptual construction of cooperative problem solving: Research based on PISA 2015. Journal of Comparative Education, 2016(3), 5.

Carroll, J. (1963). A model of school learning. Teachers College Record, 64(8), 723.

Chan, M. C. E., & Sfard, A. (2020). On learning that could have happened: The same tale in two cities. The Journal of Mathematical Behavior, 60, 100815.

DeJarnette, A. F. (2018). Using student positioning to identify collaboration during pair work at the computer in mathematics. Linguistics and Education, 46, 43–55.

Dong, L., & Kang, Y. (2022). Cultural differences in mindset beliefs regarding mathematics learning. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 46, 101159.

Elliott, S. N., & Bartlett, B. J. (2016). Opportunity to learn.

Goodlad, J. I., Klein, M. F., & Tye, K. A. (1979). The domains of curriculum and their study. Curriculum Inquiry: The Study of Curriculum Practice, 43–76.

Hao, Y., & Hu, H. (2016). Looking at the fairness of learning opportunities from classroom questions - a survey and analysis based on junior high school students in Z city. Educational Development Research, 2016(2), 7.

Laal, M., & Ghodsi, S. M. (2012). Benefits of collaborative learning. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 31, 486–490.

Langer-Osuna, J., Munson, J., Gargroetzi, E., Williams, I., & Chavez, R. (2020). “So what are we working on?”: How student authority relations shift during collaborative mathematics activity. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 104(3), 333–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-020-09962-3

Mao, Y. (2016). A qualitative study on the allocation of learning opportunities in the classroom [Doctoral dissertation, East Normal University].

OECD. (2014). PISA 2012 technical report. OECD publishing Paris.

Palincsar, A. S., & Herrenkohl, L. R. (2002). Designing collaborative learning contexts. Theory into Practice, 41(1), 26–32.

Reeves, C., Carnoy, M., & Addy, N. (2013). Comparing opportunity to learn and student achievement gains in southern African primary schools: A new approach. International Journal of Educational Development, 33(5), 426–435.

Salminen-Saari, J. F. A., Garcia Moreno-Esteva, E., Haataja, E., Toivanen, M., Hannula, M. S., & Laine, A. (2021). Phases of collaborative mathematical problem solving and joint attention: A case study utilizing mobile gaze tracking. ZDM - Mathematics Education, 53(4), 771–784. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-021-01280-z

Sfard, A. (2007). When the rules of discourse change, but nobody tells you: Making sense of mathematics learning from a commognitive standpoint. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 16(4), 565–613.

Smith, B. L., & MacGregor, J. T. (1992). What is collaborative learning.

Stevens, F. I. (1993). Applying an opportunity-to-learn conceptual framework to the investigation of the effects of teaching practices via secondary analyses of multiple-case-study summary data. The Journal of Negro Education, 62(3), 232–248.

Teng, Y. (2014). Analysis based on PISA: Which type of learning opportunities are more related to academic performance. Primary and Secondary School Management, 2014(008), 24–27.

Vernon, P. E. (1971). International Study of Achievement in Mathematics, a Comparison of Twelve Countries. JSTOR.

Wang, J. (1998). Opportunity to learn: The impacts and policy implications. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 20(3), 137–156.

Wang, D. (2018). Research on the impact of learning opportunities on domestic large-scale mathematics test results—based on the perspective of PISA mathematics test. Educational Measurement and Evaluation, 2017(04), 48–54.

Yin, Y. (2018). Equity in learning opportunities research [Doctoral dissertation, East Normal University].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Sun, Y., Yu, B. (2024). The Development and Use of Opportunity to Learn (OTL) in the Collaborative Problem Solving: Evidence from Chinese Secondary Mathematics Classroom. In: Cao, Y. (eds) Students’ Collaborative Problem Solving in Mathematics Classrooms. Perspectives on Rethinking and Reforming Education. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-7386-6_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-7386-6_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-99-7385-9

Online ISBN: 978-981-99-7386-6

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)