Abstract

In this chapter, I made use of PISA 2015’s assessment framework of collaborative problem-solving to analyze students’ discourse and evaluate students’ collaborative problem-solving abilities in both quantitative and qualitative methods. I analyzed the tasks applied in the current study and combined them with PISA 2015’s framework to formulate a detailed framework for the current study. 41 pairs and 21 groups from the project were selected as participants for the current research. Through evaluating the ability by analyzing discourse with the framework, the following results are obtained: Students’ cognition and mastery of dimensionality ability in the process of collaborative problem-solving is insufficient; students’ performance of “collaboration” in the process of collaborative problem-solving is insufficient, and there are problems such as low-level of relevant abilities and disordered discourse; students’ ability of collaborative problem-solving in peer collaboration is higher than that in group collaboration. According to the conclusion of the study, this chapter gives some suggestions and strategies to train the students’ collaborative problem-solving abilities.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

11.1 Introduction

The research on collaborative problem-solving (CPS) in China and abroad is gradually improving. In this process, experts in the education field have shown interest in the performance of Chinese students (Bai & Lin, 2016; Tan, Li, & Wan, 2018). CPS ability contains relatively complicated including cognitive, social, and metacognitive aspects (Krieger et al., 2022).

Discourse analysis, first and foremost as a linguistic study, has its own unique methodological system, with the main research methods containing critical discourse analysis (Oppong, 2017; Wang & Wu, 2017), Foucauldian discourse analysis methods (Yang & Yu, 2018), multimodal discourse analysis, etc. In the field of education, discourse analysis is particularly important in the field of classroom teaching research, and many valuable conclusions have been obtained through discourse analysis (Rogers, 2005). In recent years, the study of classroom discourse has received attention in mathematics education research, and many studies at home and abroad have provided insights into the hot topics of discourse-related research in mathematics classrooms. By studying two primary school mathematics classrooms, Gana E et al. raised the issue of mathematics classroom configuration, arguing that the semantic potential of classroom space design in mathematics teaching needs to be positively facilitated by appropriate management by teachers. Linking the management of space in the classroom (students’ desk arrangement/teacher’s position in the classroom space) to classroom discourse, a concrete dissection is made using authentic discourses from classroom videos, with the main object of study being the teacher's behavior and discursive performance. The semantics of the “perceptual space” created by the particular arrangement of the classroom desks clearly supports the methodological approach, and therefore the mindset of learning through participation in small groups. The significance of this study is that it validates the classroom effectiveness of cooperative group learning through the semantic methodology of discourse analysis, highlighting the feasibility of cooperative learning in the classroom (Gana et al., 2015). By introducing the concept of “Deliberative Dialogue”, the study explores key features of mathematics classroom practice and identifies the importance of teacher discourse in classroom teaching and learning. The study also focuses on identifying the difference between “dialogue” and “communication” from the student’s perspective, in terms of the teacher’s willingness to facilitate the democratic participation of all students. That is, whether it is a teacher–student dialogue or a student–student dialogue, it is crucial to give meaning to the judgments made in the discussion dialogue. Students often use judgment as a neutral act of language, thinking aloud and expressing meaning when understanding and accepting or not accepting their dialogue partner. This identification provides the basis for the definition of discourse in this study (Ana et al., 2015).

In the current study, I selected four Beijing LH middle school classes and collected videos and recordings of CPS in Grade 7 pairs and groups. This research focuses on the embodiment of CPS in students’ classroom discourse, analyzes the content of students’ classroom discourse, and combines the 12 three-level sub-dimension skills in the PISA 2015 CPS evaluation framework, based on quantitative research discourse. The standard for assessing ability level in PISA 2015 is to evaluate and research students’ CPS in math classroom videos. Based on the literature on CPS and discourse analysis and the status quo of collaborative group teaching in domestic mathematics classrooms, this chapter attempts to explore the following issues:

-

(1)

How to evaluate students’ ability to solve collaborative problems through classroom discourse?

-

(2)

What sub-dimensions of CPS abilities are reflected in students’ discourse, and what differences in CPS abilities exist in teams with different numbers of students?

-

(3)

What is the students’ CPS level in the experimental classroom?

High-level abilities such as CPS skills have gradually become the focus of the education field and key abilities required for future talent development. The research of this paper is based on previous research and evaluation and has the following research purposes and significance.

This section of the study expands on previous research and assessments to examine students’ discourse performance in Chinese classrooms and improve students’ CPS skills in a targeted manner, using international assessment framework items. It is hoped that identifying the strengths and weaknesses of students’ CPS processes will provide a basis for subsequent targeted development of students’ CPS skills. This study is aligned with international education and explores the elements of skills for developing international talents.

11.2 Research Method

11.2.1 Subject and Methodology

11.2.1.1 Participants

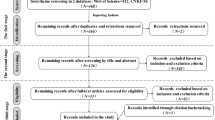

Based on the specific research process, the author selected student pairs and groups from the project that meet the following screening criteria. First, the selected classes must use the same set of collaborative problems. At the same time, the teacher must rarely interfere with the students’ collaborative process, limiting themselves to issuing and explaining tasks, patrolling, and solving students’ problems not related to the collaborative problems in the classroom. Second, the names in the student pairs and groups must correspond with those of the students in the video, and the recordings of their conversations must be clear and legible. Third, the composition of the pairs and small groups must meet the project design requirements. Specifically, two pairs formed one group, the collected pair and group student task sheets had to be fully completed, and the pair group names and numbers had to be clear.

Based on the above screening criteria, videos and recordings of six classes were screened to select appropriate classes with pairs and groups. After screening, the selected classes for the study were 1a, 1b, 3a, and 3b, which included 41 pairs and 21 groups. The specific number of pairs and groups in each class is described in the subsequent data analysis section, as shown in Table 11.1.

11.2.1.2 Research Methodology

A combination of qualitative and quantitative research methods was used to study the CPS processes of students’ pairs and groups in the experimental classroom videos.

-

1.

Qualitative research methods

This study used the PISA 2015 CPS framework (Fig. 11.1) to briefly analyze the CPS of the students who participated in the experiment. We evaluated student performance in each dimension of the CPS process based on the levels of each ability dimension given in PISA 2015. This is also the main body of this study.

This was done by textual transcription of the video and recording samples. First, we analyzed specific questions from the pair and group collaborations in the video. We set specific discourse criteria for each level of the 12 three-level dimensions of competence in the PISA 2015 framework, classified students’ discourse competence and level based on the criteria, and then conducted statistical analysis to conclude the study. The findings of the study are also summarized and analyzed.

-

2.

Quantitative research methods

Based on the students’ discourse in each group during the collaboration, the specific number of words and discourse rounds in the students’ pairs and groups were counted to obtain relevant statistical results, which were combined with the results of the qualitative analysis to draw relevant research conclusions.

11.2.1.3 Data Collection Methods

Since this experiment focuses on students’ discourse, the main data sources were recordings of students’ actual collaborative processes. Using the project team’s recording equipment, the video recorder and audio channel parameters were adjusted before recording to facilitate subsequent transcription of each student’s discourse. At the same time, students’ pair and group work produced paper results. The paper results from the pairs and groups needed to be accurately collected to evaluate the CPS level. To match the paper results with the experimental pairs and groups, the project team contacted the classroom instructor in advance and asked them to assist in pre-grouping the pairs and groups on the printed pair and group problem-solving task sheets. In this way, the groups were tailored to the actual classroom situation and met the experimental requirements.

Following experimental design and data collection principles, the project team experimented smoothly and collected several experimental groups with better effects, including 41 pairs and 21 groups. Among them, the experimental groups with better effects had the following characteristics: the names and genders of group members were identified, two pairs corresponded with one group, the recorded discourse was clear and legible, and the task sheets were collected completely.

11.2.1.4 Discourse Analysis and CPS Evaluation

The main body of this study is an analysis of student discourse in the CPS process, so student pair and group recordings were the original data used and analyzed. Based on the research questions, the analysis of student discourse data was conducted based on the following analysis steps.

First, recordings were transcribed to obtain the actual conversation of each student participating in the discussion. The transcription must match the words with the students’ names to ensure the study’s authenticity, and so must be done against the video.

After obtaining the transcripts, each student’s discourse was analyzed in combination with CPS levels. The discourse that showed CPS was marked and the levels classified based on the PISA 2015 framework. After level delineation, the approximate level of CPS ability demonstrated by each student in the experimental situation could be obtained and the relevant research conclusions reached by analyzing and briefly comparing the differences in students’ abilities in conjunction with the specific CPS process.

After getting each student’s score, a comprehensive evaluation of students’ CPS ability within the same group was conducted to obtain the comprehensive ability level of group cooperation. Then, the experimental groups’ differences in CPS ability were analyzed to obtain relevant research conclusions.

Since each student was involved in two collaborations (pair and group), depending on the different collaborative problems, it was possible to obtain the same student’s performance twice in two collaborative problem situations and analyze it based on the level of competence dimensions demonstrated in both collaborative processes, enabling the researcher to make relevant research conclusions.

11.2.2 Scientific Justification of Evaluation Criteria

The PISA 2015 discourse framework was the main evaluation criteria used in this study. The scientific validity of this evaluation criterion is demonstrated to ensure the rationality, rigor, and validity of the ensuing analysis and demonstrate its real value.

11.2.2.1 Rationality of the Theoretical Level

The evaluation criteria in this study used the PISA 2015 framework to assess CPS and were modified and improved based thereon to make the evaluation criteria more suitable for the complete assessment of students’ CPS skills in real classrooms.

At the theoretical level, the PISA 2015 framework is relatively well developed. It has been administered to 9,800 15-year-old students in China, and the corresponding results have been obtained. Some educational researchers have evaluated the rationality of this framework, arguing that PISA 2105 focuses more on the collaborative dimension in defining skills for CPS. The four problem-solving skills dimensions intersect with the three collaborative skills dimensions, implying that the collaborative and problem-solving dimensions are interwoven in evaluating students’ skills in each sub-dimension. The 12 skill sub-dimensions contain information on both the collaborative and problem-solving dimensions (OECD, 2017a). That is, this framework decomposes the CPS process into 12 sub-processes where collaboration and problem-solving intersect, and the skills embodied in each process are evaluated separately. In this framework, 12 sub-dimensional CPS skills form an organic whole and do not cross over and work together.

The PISA 2015 framework was selected for refinement in this study, taking into account students’ cognitive characteristics and how CPS skills are reflected in students’ discourse. The PISA 2015 test questions on CPS show that students’ responses to items reflect their cognition in specific problems. Therefore, in this study, the essence of the evaluation was to concretize students’ “responses” in the CPS process, analyze their discourse, and evaluate the concrete expression of their CPS from their discourse, in line with the Item Response Theory used in the PISA 2015 assessment of students.

11.2.2.2 Rigor of the Development Process

As the evaluation criteria are important for this study’s authenticity and reliability, their development process is described and its rigor demonstrated.

After analyzing and sorting the PISA 2015 and ACT21S frameworks, we selected the PISA 2015 framework as it is more suitable for our students and has been used in their assessment. The researcher provided experts and teachers with evaluation examples, invited their comments and suggestions for improvement, and made modifications and improvements based on their opinions.

In the above process, the contact between the researcher and the experts and teachers was one-way. The experts and teachers did not interact. The researcher summarized their opinions and synthesized them for revision to ensure they were objective and rational. Furthermore, the experts and teachers focused on the evaluation criteria differently: the education research experts paid more attention to differences in ability levels and the match between student discourse and ability; the secondary school mathematics teachers focused on student performance and discourse content and evaluating students’ discourse performance. Combining the two perspectives resulted in a more refined version.

11.2.2.3 Practice-Level Validity

To verify the PISA 2015 framework’s validity in this application, three project group members were invited to evaluate the same student's discourse in a CPS process about the discourse evaluation criteria; the researcher then analyzed and compared the abilities and levels based on the three members’ evaluations.

Analysis of the same discourse fragment, conducted after the project team members had become familiar with the evaluation criteria, revealed a concentration of sub-dimensional competence items and subtle differences in level delineation. After the discourse evaluation, project team members were invited to analyze this fragment briefly. The project team members centered their analysis on the skills reflected in the students’ discourse, described the main skill characteristics of two students in the peer group, and analyzed why their abilities were at a certain level.

In summary, the discourse evaluation criteria for CPS skills in this study were valid and helped the researcher grasp students’ CPS skills and corresponding levels efficiently.

11.2.2.4 Realistic Value

Evaluation studies of group collaboration have been the focus of many educational researchers and front-line teachers and are important for evaluating the learning effects of group collaboration and students’ collaboration levels. In many studies, the evaluation of group collaboration focuses on students’ collaborative outcomes, usually using paperwork, group reporting, or developing a series of process evaluation forms for students to self-evaluate (Cao & Bai, 2018). Such an evaluation approach is biased toward evaluating students’ competence or skills in the problem-solving dimension and is weaker in evaluating the level of students’ competence in the collaboration dimension.

The CPS sub-dimensional ability level classification and discourse evaluation criteria in this study were based on students’ classroom discourse, which provides a specific and detailed evaluation of each student involved in the cooperative, fully taking into account students’ equal participation in the cooperative, the organic integration of the collaborative and problem-solving dimensions, and avoiding situations where collaborative results or group reports are done by fixed members alone.

CPS is a student-led process, and the teacher cannot intervene in each student group’s collaboration. However, in guiding their collaboration, teachers can capture students’ discourse in the collaboration process and make timely evaluations in conjunction with this discourse evaluation standard to grasp students’ performance of related abilities, which can help teachers deeply grasp students’ learning, thinking, and ability development.

Moreover, due to the rapid development of information technology, more tools and techniques can be added to classroom teaching to assist teaching and learning and evaluate teaching effectiveness. It is believed that the popularization of related technology facilities will make collecting and transcribing students’ classroom discourse simpler and enable teachers to obtain and evaluate students’ discourse easily and quickly. The PISA 2015 framework will provide teachers with powerful guidelines for assessing students’ CPS.

11.3 Study Results

11.3.1 Results of Quantitative Statistics and Qualitative Analysis of Students’ Collaborative Discourse

11.3.1.1 Description of the Experimental Object Number

The data selected for this study were drawn from four classes and included 41 pairs and 21 groups. Two classes were experimented on each time, numbered 1a and 1b, and 3a and 3b.

After transcribing the pair and group recordings from the four selected CPS classrooms, 41 pair collaborative discourse texts and 21 group collaborative discourse texts were obtained. These transcribed discourses were first counted to obtain visual statistics on the number of words and conversation rounds.

Based on existing research, quantitative classroom discourse analysis provides strong evidence for researching and improving teacher–student relationships. In CPS research, the number of words and conversation rounds can complement qualitative research and provide valuable results and conclusions.

The pairs and groups were numbered as follows: “class - group number - pair number”; thus, 1a-3–2 means the second pair in the third group of study class 1a, with students in 1a-3–1 and 1a-3–2 forming the third group. Four data groups from each studied class were used for data comparison clarity.

11.3.1.2 Discourse Volume Statistics

The number of words between students’ pairs and groups was counted, and the results for each studied class are as follows (Tables 11.2, 11.3, 11.4, 11.5).

11.3.1.3 Statistics of the Number of Conversation Rounds of Conversation

The number of conversation rounds in the words of the collaborative process between students’ pairs and groups was counted for each studied class, as follows (Tables 11.6, 11.7, 11.8, 11.9).

As can be seen, the number of words and conversation rounds varied widely among pairs and groups. It is impossible to tell students’ CPS process and related ability level from the data, and in-depth qualitative discourse analysis is needed.

11.3.2 Results of Discourse Analysis in Student Pair and Group CPS

After determining the sub-dimensional ability and level classification of the 41 pair and 21 group collaboration discourses, the comprehensive data were processed to obtain the analytic results.

The 12 three-level sub-dimensional skills in the PISA 2015 assessment framework were numbered to facilitate the subsequent description of the specific levels of collaboration problems. The four second-level dimensions of the problem-solving competency dimension corresponded to A, B, C, and D, and the three second-level dimensions of the collaboration competency dimension to 1, 2, and 3, respectively; as such, the 12 third-level dimensions corresponded to A1-A3, B1-B3, C1-C3, and D1- D3, as follows:

Discovering team members’ perspectives and abilities (A1); Discovering the type of collaborative interactions and goals used to solve the problem (A2); Understanding students’ roles in solving the problem (A3); Building a shared representation and negotiating the meaning of the problem (common ground) (B1); Identifying and describing tasks to be completed (B2); Describing roles and team organization (communication protocol/rules of engagement) (B3); Communicating with team members about the actions to be/being performed (C1); Enacting plans (C2); Following the rules of engagement (e.g., prompting other team members to perform their tasks) (C3); Monitoring and repairing shared understanding (D1); Monitoring results of actions and evaluating success in solving the problem (D2); Monitoring, providing feedback, and adapting the team’s organization and roles (D3).

These 12 three-level dimensions are expressed in four, letter grade levels running from high to low: E (Excellent), G (Good), F (Fair), and P (Poor).

The frequencies of the demonstrated CPS three-level competence dimensions for all participating students are shown in Table 10, with separate statistics for different groups.

As can be seen from Table 11.10, the sub-dimensional skills appearing with high frequency (frequency ≥ 10%) in pair collaboration were B1 and D1; the sub-dimensional skills appearing with high frequency (frequency ≥ 10%) in group collaboration were A1, B1, B3, C1, C3, and D1. At the same time, it can be seen that the frequency of sub-dimensional skills’ occurrence in pair and group collaboration differed significantly (|difference in frequency| ≥ 4%): A2, B3, and D1.

Based on the above ideas, the same can be derived for each pair and group level in Table 11.11.

More than half of the students in both pair and group collaboration (56.89% and 66.86%, respectively) were “Good,” while 29.64% and 31.41%, respectively, were “Fair.” More students (12.60%) were “Excellent” in pair collaborations than in group collaborations (0.43%), while slightly more were “Poor” in group collaborations (1.30%) than in pair collaborations (0.87%). Table 11.12 shows the level of each competency dimension demonstrated by the students, based on the above statistics.

In pair collaboration, the highest percentage of students showing an “Excellent” level were in A1 (32.53%), followed by C1 (24.39%). B3 performed poorly in pair collaboration compared to other sub-dimensions, with a “Poor” percentage of 2.41%. There were almost no “Excellent” sub-dimension levels in group collaborations, except for B3, which had an “Excellent” level of 3.19%. This competency also showed more “Poor” levels (3.19%), while the remaining sub-dimensions had a higher percentage of “Good” levels.

11.3.3 Level of Students’ CPS Skills

The weights assigned to each sub-dimension of CPS by the PISA 2015 framework are shown in Fig. 11.2. The weights of the sub-dimensional skills were calculated based on this criterion.

The weights for the”Exploring and understanding (A)” and “Representing and formulating (B)” secondary sub-dimensions equalled 40% when combined as the “AB dimension,” reducing the 12 sub-dimensions to nine. The weights of dimensions 1, 2, 3, and dimensions AB, C, and D Were calculated as follows: the weight vector of secondary dimensions AB, C, and D was \(\alpha = \left( {{\text{40\% }},30\% ,30\% } \right)^{T}\), and the weight vector of secondary dimensions 1, 2, and 3 was \(\beta = \left( {{\text{45\% }},{25}\% ,3{0}\% } \right)^{T}\), , based on which the following 3*3 weight matrix can be formed:

The four levels were scored from 4 to 1 (highest to lowest) based on the above matrix. The level scores for each sub-dimensional competency were obtained by multiplying the percentage of each level in Table 11.12. The weight matrix P was then multiplied by each ability level score to obtain the overall pair and group CPS.

As can be seen from Table 11.13, only A1 in pair collaboration scored more than 3; A3 in pair collaboration and C2 in group collaboration scored 3.00. The level score of C2 in pair collaboration was 3.00. The remaining sub-dimensions scored below 3, with the lowest scores being 2.52 and 2.55 for pair and group collaboration in A2.

Based on the scores in Table 11.13 and the calculation method shown above, the overall competence scores for all subjects in pair and group problem-solving were calculated to be 2.85 and 2.69, respectively, which is at the “Fair” level.

11.3.4 Description of Discourse Analysis Results

11.3.5 Results of the Qualitative Study Analysis

Based on the PISA 2015 assessment framework and data from previous calculations, more detailed sub-dimensional level results were obtained, and the experimental groups reflected some more common results. The more prominent results are now described in preparation for the subsequent conclusion analysis.

-

1.

Students’ discourse performance was more prominent and occurred more frequently in certain sub-dimensions.

Table 11.10 shows that the sub-dimensions D1 and B1 were more prominent in both pair and group collaboration; the sub-dimensional skills that emerged were richer. The sub-dimensional skills that emerged in group work were richer, with more CPS sub-dimensions represented in student discourse than in pair collaboration.

-

2.

Students performed better in “establishing and maintaining shared understanding (1)” during the CPS process.

As can be seen in Table 11.11, students’ performance in sub-dimensions A1 and C1 under the “Establishing and maintaining shared understanding(1)” secondary sub-dimension in the pair collaboration showed an “Excellent” level of discourse performance. C1 showed outstanding discourse performance at the “Excellent” level and the two sub-dimensions also performed better in group collaboration, indicating that students’ inquiry in and understanding of the problem-solving perspective were better than in the other sub-dimensions.

-

3.

Students’ discourse in pair and group showed slight differences in sub-dimensions, but the differences were not significant.

In comparing the sub-dimensions of the same students’ discourse in the two cooperative groups, the main differences were that some students showed more ability in team management and role adaptation with a larger number of collaborators. In contrast, some students showed less discourse in describing and analyzing problems, and more passive discourse in monitoring, refining, and giving feedback. As can be seen, in addition to their differences in discourse content, students also showed slight differences in dimensions. From the data, B3 was higher in group collaboration than in pair collaboration, while D1 was lower.

-

4.

Students’ CPS skills were at a “Fair” level.

Students’ CPS level scores generally ranged from 2.50 to 3.00 (i.e., from middle- to upper-level “Fair” to “Good”), with the highest score being only “Good.” The overall pair and group problem-solving ability scores were between “Fair” and “Good,” but still belonged to the “Fair” level.

11.3.6 Quantitative Analysis Results

-

1.

The number of words reflected students’ general CPS level from the side.

The typical case study of CPS in pair and group from the previous chapter showed that the fewer words students spoke, the fewer their possible competency dimensions and the weaker their CPS level. Therefore, frequency statistics on student discourse can provide evidence of students’ CPS level in pairs and groups: students with fewer words have fewer types and numbers of CPS competence sub-dimensions in pairs and groups and vice versa. However, there are still exceptional cases. For example, students who engaged in discussions about unrelated topics during the collaborative process showed a lot of discourse, but their CPS sub-dimensions were less diverse and lower.

-

2.

The number of rounds students spoke also reflected their approximate level of CPS in mathematics.

In two different CPS processes, students with a significantly lower number of discourse rounds than other team members showed a more homogeneous dimension of competence in their discourse. Students with more discourse rounds communicated more with other team members, monitored and provided more feedback to other team members in their discourse, and showed more sub-dimensions of competence, with each competence at the “Good” level.

11.3.7 General Discussion

Some conclusions can be drawn by combining the two perspectives, as described below.

An overall analysis of the participating students’ discourse revealed that among the 12 dimensions, students generally excelled in the secondary sub-dimension of the collaborative competency dimension (“Establishing and maintaining team organisation”) and its four tertiary competency dimensions, which intersect with all secondary sub-dimensions under the problem-solving dimension and reflected the highest percentage of student discourse (i.e., A1, B1, C1, and D1 of the framework).

The experimental students’ approximate CPS level can be obtained based on the CPS sub-dimensions reflected in their discourse.

Table 11.12 shows that students showed more of the highest levels for each ability dimension in pair collaboration but almost none at the highest levels in group collaboration; the frequency of the lowest levels of ability was also low, mainly in the “Good” and “Fair” levels, consistent with the PISA 2015 test results.

11.4 Conclusion and Implications

11.4.1 Discussion

The results and conclusions from the previous section showed the approximate level of CPS exhibited by some students in the experimental setting. This study provides an experimental basis for teachers to organize collaboration and develop students’ higher-order abilities in authentic classrooms and offers implementation suggestions and strategies.

From the PISA 2015 CPS assessment results, it appears that the 9800 15-year-old students from four provinces and cities (Beijing, Shanghai, Guangdong, and Jiangsu) who participated in the test did not perform well (26th globally, the international average) and performed poorly compared to test rankings in mathematics and science subjects (OECD, 2017b).

PISA 2015 assessed students’ CPS abilities through conversational agents (OECD, 2017a), while the current research is situated in a face-to-face context. Detailed analysis of the PISA 2015 test results indicates that the dimensions in which participating students’ performance differed significantly from that of top-ranked Singaporean students were similar to the results of this experiment: the students participating in this study performed worse in the “Enacting plans” (C2) and “Identifying and describing tasks to be completed” (B2) CPS sub-dimensions, consistent with Chinese students’ performance in PISA 2015.

It can be seen that Chinese students’ CPS in mathematics is still somewhat different from that of the international leaders and that their performance in some important skills still needs to be improved and depends on teachers’ guidance and development. Therefore, based on the PISA 2015 and this study’s findings, some strategies can be offered for implementation in real classrooms.

11.4.2 Conclusion

-

1.

Students’ awareness and mastery of the sub-dimensional skills in CPS was inadequate.

Some dimensions were not reflected or rarely reflected in the student discourse, such as: “Discovering the type of collaborative interaction to solve the problem, along with goals (A2),” “Understanding roles in solving the problem (A3),” and “Enacting plans (C2),” all of which occurred less than 10% of the time, indicating that students’ awareness and mastery of these competency dimensions was low.

-

2.

Students’ collaboration in the CPS process was inadequate, with low levels of relevant skills and disorganized discourse.

Of the two dimensions of discourse performance, the “problem-solving” dimension performed better, and students’ inquiry and understanding of the problem was the most frequent part of the CPS process. The collaboration dimension’s discourse performance was less frequent and at a lower level. Previous research found student attitude toward collaboration may have an influence on their CPS skill performance (Wang & Ning, 2019), while in current research through analysis of students’ dialogue revealed that, with minimal teacher guidance and intervention, students’ CPS process was chaotic and progressed in a slightly disorganized manner, and they analyzed problems in a continuous cycle, always with unclear goals. The skill and level evaluation revealed that when students could not reach an agreement within a group, they usually sought help from the teacher rather than solving the problem through collaborative inquiry, indicating they paid insufficient attention to CPS skills and were not conscious of using collaborative inquiry to solve problems.

-

3.

Students had slightly higher levels of CPS skills in pair collaboration than in group collaboration, and team organization, management, and monitoring discourse were more likely to be reflected in group collaboration.

Student pairs’ problem-solving skills levels were slightly higher than their group problem-solving levels. Students’ discourse ability and content showed that pair collaborations were slightly more efficient in problem-solving than group collaborations, with students reaching agreement through dialogue more efficiently, thus completing the requirements of the problem. In contrast, group collaboration discourse performance revealed the weakness of students’ ability to collaborate. Given more open-ended questions and more time for collaboration, group collaboration progressed significantly less than pair collaboration. Organization, management, and monitoring during solving problems are critical for successful teams to transfer discussion to an executable plan (Chang et al., 2017). While in the current research, the sub-dimensions of team organization, management, and monitoring, such as B3 and D3, were more likely to emerge in groups with larger numbers of collaborators, suggesting that the number of students involved in the collaboration affected CPS effectiveness.

-

4.

The diversity of sub-dimensional skills reflected in individual student discourse was low, and the CPS skills level was “Fair.”

Setting aside the dimensions that rarely appeared in the collaborative process, the remaining dimensions were unevenly represented in the student discourse. Students’ discourses contained a fixed number of dimensions, indicating that the diversity of the skill dimensions reflected therein was low. Students’ CPS skills scores were low, with both pair and group CPS skills being scored “Fair,” below higher-level requirements and indicating a need for additional training.

11.4.3 Insights

-

1.

Teacher-Targeted Development Recommendations and Strategies

Students already have some experience with and understanding of group work. They do not need instruction in the areas where they have a better grasp of the skills, but should learn more in those areas where they perform less well (Hao & He, 2019). Based on this study’s findings, teachers should target the following aspects through developmental education.

This study’s findings clearly show some sub-dimensional skills should be focused on when instructing students, beginning with the most basic. “Discovering the type of collaborative interaction to solve the problem and setting goals (A2)” and “Enacting plans (C2)” are skills that reflect students’ ability to take appropriate actions to solve problems; however, most students do not demonstrate them, indicating that they are weak in this area. Teachers should make a conscious effort to develop students’ skills in these two areas in their daily teaching.

Increasing students’ awareness of types of interactions is one strategy that can be implemented. Since students are unaware of the interactions needed to solve problems, they may have never heard of a given type, similar to a machine facing an interacting object. Therefore, before engaging in CPS, teachers need to introduce students to interaction, a key element in the social networking domain, by simply and easily introducing students to one-to-one, one-to-many, many-to-one, and many-to-many types of interaction and their meanings (Cao & He, 2009). This will give students a basic understanding of how computers and networks work and provide some insight into how to conduct CPS, prompting them to discover and select the type of interaction needed to solve problems in a collaborative process, increasing their awareness of this competency dimension, and improving their level of competence.

Strengthening students’ planning skills and developing their plan-making habits is another strategy. Planning ability rarely appeared in previous cooperative learning instruction and improvement strategies, because teachers’ guidance often accompanies students’ cooperative learning process. It is rare for students to carry out complete problem-solving on their own in domestic classrooms. To develop students’ planning skills, teachers need to give them more freedom to think independently and design their problem-solving steps, thereby improving their planning skills.

-

2.

Suggestions and Strategies for Systematic Teacher Development

CPS is a higher-order ability with high complexity, involving the compounding of many dimensional abilities (Yuan & Liu, 2016). Targeted cultivation is significant for improving students’ sub-dimensional ability, with the ultimate goal of enhancing students’ CPS ability. Therefore, once students’ sub-dimensional abilities have been improved, teachers should systematically guide students’ CPS to strengthen their cooperative awareness and collaboration ability.

Organizing CPS at the right time helps train students’ CPS skills in real situations. Students’ ability to improve must be trained in real-life situations, using appropriate methods to improve their overall quality, ability, and knowledge. Therefore, teachers should design problems that fit the teaching schedule and are suitable for cooperative learning, while completing their normal teaching. Let students experience the CPS process completely, then evaluate and self-evaluate to improve their CPS ability in a continuous improvement process.

Teachers should provide timely guidance in student collaboration to strengthen students’ mastery of the CPS process. Their leadership is integral to students’ learning process and their collaborative process guidance helps students collaborate more efficiently, gradually find the rhythm of and methods for collaborative learning, and improve their CPS skills.

This study has some limitations. The samples selected for this study were four classes from two schools in the same area. Through analyzing data in PISA 2015, it was found that CPS skills varied between different schools in China mainland (Tang, Liu & Wen, 2021). Due to the small sample size, more samples are needed to obtain more generalizable findings. Moreover, the classroom video used in the study captured an experimental scenario, which is somewhat different from a normal teaching schedule and a real classroom situation.

CPS skills are receiving attention in various countries due to international talent development needs. As a large-scale assessment linking countries, the PISA test is a powerful tool and model for research in this area. In future research, education field research in China could conduct a series of localized studies based on students’ performance in the PISA test to assess and study their intellectual and cultural characteristics and provide more rigorous and accurate ways of cultivating talents with higher-order abilities.

References

Bai, Y., & Lin, P. (2016). 合作问题解决的概念建构——基于PISA2015 CPS的研究[The Construction of CPS concept: Based on PISA2015 CPS Studies]. Primary & Secondary Schooling Abroad, 3, 52–56.

Cao, M., & Bai, L. (2018). 面向数学问题解决的合作学习过程模型及应用[Cooperative Learning process model for mathematical problem-solving and its application]. e-Education Research, (11), 85–91.

Cao, Y., & He, C. (2009). 初中数学课堂师生互动行为主体类型研究——基于LPS项目课堂录像资料[Research of the type of teacher-student interaction behavior subject in junior middle school mathematics classroom on the LPS video date]. Journal of Mathematics Education, 05, 38–41.

Chang, C. J., Chang, M. H., Chiu, B. C., Liu, C. C., Chiang, S. H. F., Wen, C. T., ... & Chen, W. (2017). An analysis of student collaborative problem solving activities mediated by collaborative simulations. Computers & Education, 114, 222-235.

Gana, E., Stathopoulou, C., & Chaviaris, P. (2015). Considering the classroom space: Towards a multimodal analysis of the pedagogical discourse. Educational paths to mathematics: A CIEAEM sourcebook, pp. 225–236.

Hao, J., & He Q. (2019). [Collaborative problem-solving ability and its assessment practice]. China Examinations, (09),11–21+31.

Krieger, F., Azevedo, R., Graesser, A. C., et al. (2022). Introduction to the special issue: The role of metacognition in complex skills - spotlights on problem solving, collaboration, and self-regulated learning. Metacognition Learning, 17, 683–690. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-022-09327-6

Liang, Y., Zhao, C., Ruan, Y., Liu, L., & Liu, D. (2016). 网络学习空间中交互行为的实证研究——基于社会网络分析的视角[An empirical study of learners’ interaction in the online learning space: Under the perspective of SNA]. China Educational Technology, 07, 22–28.

OECD. (2017a). PISA 2015 assessment and analytical framework: Science, reading, mathematic, financial literacy and collaborative problem solving, revised edition, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264281820-en.

OECD. (2017b). PISA 2015 results (Volume V): Collaborative problem solving. PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264285521-en

Oppong, Yaw N. (2017). Evaluation of a management development programme: a critical discourse analysis[J]. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal, 12(1), 68–86.

Tan, H., Li W., & Wan, X. (2018). 国际教育评价项目合作问题解决能力测评:指标框架、评价标准及技术分析 [Assessment of collaborative problem-solving ability in international education assessment programme: Index framework, assessment standard and technical analysis]. e-Education Research, (09), 123–128.

Tang, P., Liu, H., & Wen, H. (2021). Factors predicting collaborative problem solving: Based on the data from PISA 2015. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 6, p. 619450). Frontiers Media SA.

Wang, L., & Ning, B. (2019). 协作态度对协作式问题解决能力的影响: 学生幸福感的中介作用—基于中日两国PISA2015数据的比较研究 [Cooperative attitude and collaborative problem-solving : The mediating effect of student’s happiness—based on a comparative study of PISA2015 Data Between Japan and China]. Primary & Secondary Schooling Abroad., 12, 2–10.

Wang, S. & Wu, Y. (2017).论学生课堂教学参与中教师的话语能力—基于费尔克拉夫批判话语分析理论的探析[teachers’discourse competence in classroom which student engaged —A theoretical exploration from the perspective of critical discourse analysis]. Teacher Education Research, 29(06), 29–34.

Yang, X., & Yu L. (2018). 兰开斯特的预言与iSchool的抱负:跨时代的话语分析 [Lancaster’s prophecy and iSchool’s aspiration: A cross-time discourse analysis]. Journal of Library Science in China, 44(235)(03), 6–22.

Yuan, J., & Liu, H. (2016). 合作问题解决能力的测评: PISA2015和ATC21S的测量原理透视 [The measurement of collaborative problem-solving: Analyzing of the measuring principle of PISA2015 and ATC21S]. Studies in Foreign Education, 12, 45–56.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Du, B. (2024). Research on the Evaluation of Students’ Collaborative Problem-Solving. In: Cao, Y. (eds) Students’ Collaborative Problem Solving in Mathematics Classrooms. Perspectives on Rethinking and Reforming Education. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-7386-6_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-7386-6_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-99-7385-9

Online ISBN: 978-981-99-7386-6

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)