Abstract

Coherently with the life course perspective that studies individual life trajectories embedded in sociohistorical changes, this chapter offers a synthesis on the long-term dynamics of vulnerabilities in old age that are associated with a deficit of reserves. In a first time, we investigate how economic, social and health reserves have been unevenly constructed across long lives. The impact of social stratification in the early stage of life, the institutionalization of the life courses and the process of accumulating (dis)advantages are confronted. In a second time, we show how the results of those life course dynamics, the unequal distribution of reserves older adults have to cope with aging, changed during the last 40 years. Undeniable progresses also resulted in new inequalities, or the accentuation of older ones. Third, challenging the classical perspectives of political economy of ageing and social gerontology, we show that depletion is not a linear process but that social inequalities and life accidents play a role. Moreover, coping mechanisms are considered since they tend to be based on reserves’ activation while preserving a level of reserves, for further ageing challenges.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

From 2010 onwards, a line of research emerged within the LIVES project (see Spini & Widmer, 2022) that focused on older adults and emphasised the dynamic relationships between progress and inequality. This research was based on the main hypothesis of a growing divide between a majority who benefit from better health and living conditions in old age and a marginalised minority of vulnerable elderly people who do not (Oris et al., 2016). Over the following decade, numerous analyses were added to this line of research that document how, throughout their life courses, individuals construct social and economic reserves that they can use in their old age to maintain a sense of self (Spini & Jopp, 2014) and well-being (Oris, 2020). This newly developed concept of reserves is especially fruitful for the study of old-age vulnerabilities since it refers to resources that are not required for immediate use but that, if accumulated to a sufficient extent, allow individuals to recover from accidents, face stressors, or manage difficult transitions (Cullati et al., 2018), such as growing old.

The foundation for our empirical work is the CIGEV-LIVES Vivre-Leben-Vivere survey (VLV) (Oris et al., 2016). It focuses on the health and living conditions of older adults born between 1911 and 1946 living in Switzerland. The first wave of VLV, conducted in 2011–12, was specifically constructed to promote a fair inclusion of vulnerable individuals—those living in poverty, social isolation, depression or those physically dependent on external care. A total of 3080 individuals without major cognitive impairments aged 65–102 were included in the survey via a two-step procedure. First, they completed a self-administered questionnaire that included a retrospective life calendar covering their family, work and residential trajectories from their birth until the date of the survey (Morselli et al., 2016). Following this, they participated in a computer-assisted personal interview. A total of 555 individuals with neuropsychiatric or major physical impairments were added via a simplified procedure (Oris et al., 2016). All coauthors of this chapter were actively involved in this data collection. A second wave of the VLV survey was carried out in 2016–17 (see Ihle et al., 2020). The chapter by Andreas Ihle and colleagues (this book) addresses a full branch of research on the interdisciplinary understanding of cognitive and relational reserves in old age based on VLV data. This chapter focuses on social and economic reserves. In the first part, we provide a synthesis of how the dynamics of these reserves are constituted across people’s lives. Following the LIVES vulnerability framework (Spini et al., 2017), individual life trajectories are considered in their sociohistorical contexts. Cohort membership bridges micro- and macrohistories. In the second part, the use and depletion of accumulated reserves in old age are discussed.

The Sociohistorical Construction of Older Adults’ Social and Economic Reserves

We studied individuals who have been socialised, roughly, between 1910 and 1965, a period marked by major economic, social and institutional changes, a historical transition from highly prevalent poverty to a middle-class consumer society. Across history and throughout each individual’s life, reserves have been unevenly constructed. The acquisition of a certain level of education is foundational and illustrates the reserve concept well, i.e., a latent capability that can be mobilised when needed (Cullati et al., 2018). In Switzerland, free compulsory primary school and child labour prohibition were established as early as the 1870s. In the twentieth century, the Swiss educational system offered increasing opportunities. In 1930, the landmark institutionalisation of vocational training occurred, with the aim of training skilled workers and ensuring socioeconomic stability in Swiss society. In doing so, Switzerland adopted a system that is largely specific to German-speaking countries, where this type of professional training is highly valued (Allmendinger & Leibfried, 2003). Overall, the Swiss educational system promoted social reproduction until the early 1960s. The expansion of secondary and tertiary degrees is reflected in the changes in the composition of the elderly population. In 1979, 66 percent of those aged 65 and older had completed only the compulsory level of education or less; in 2011, this was the case for only 18 percent of that population. The proportion of the older population with an average level of education (mainly apprenticeship) grew from 23 to 50 percent (Oris et al., 2017).

Schools acted as phasing institutions (Levy & Bühlmann, 2016) that facilitated the transition from education to the labour market. Analysis of the VLV life calendars revealed four typical professional trajectories: full employment, quasi full employment, stop and restart, and start and stop. In the aforementioned birth cohorts, men predominantly experienced the first two trajectories, whereas women predominantly experienced the latter (Gabriel et al., 2015). A biographical mixed-methods approach that combined quantitative analysis of VLV data with interviews of a subsample confirmed that women had been socialised to adopt the stereotypical female role of spouse, mother, and housewife (Duvoisin & Oris, 2019). Similarly, a gendered attribution of skills framed school programs, with girls being constrained to studying the domestic economy (Baeriswyl, 2016, p. 106). As will be discussed below, such limitations held tremendous implications for the constitution of women’s reserves and their use later in life.

In the context of improvements in the standard of living after World War II, a postcompulsory diploma offered a stable professional career and the corresponding financial income to sustain a middle-class lifestyle, which also promoted a normative model of the family: a nuclear household with a male breadwinner and a woman acting as mother and housewife (Baeriswyl, 2016). Neither in Switzerland nor in the rest of the Western world has marriage been as frequent, early and long-lasting as among the parents of the baby boomers, parents who now constitute the VLV sample. Analyses that simultaneously consider familial and professional trajectories have, however, shown that not one but several trajectories led to this rise in fertility. Although interviews have confirmed the weight of gendered social norms, real diversity was created by social position, life experiences and agency (Duvoisin, 2020; Duvoisin & Oris, 2019).

Nevertheless, it must be emphasised that many members of the birth cohorts studied in VLV (1911–1946) have experienced standardised life trajectories, which is due largely to the institutionalisation of the life course following WWII, defined in three stages: childhood, adulthood, and old age (Kohli, 2007). After the first stage, the transition to adulthood followed a clear sequence of events (typically, first job, leaving parental home, first marriage, first child) (Duvoisin, 2020). To support the next life stage, Swiss Old Age and Survivors’ Insurance (AVS), which was supposed to guarantee a minimum pension to all Swiss residents, was instituted in 1948, thus fixing retirement and the transition to old age at the age of 63 for women and 65 for men. The AVS was only supplemented by an occupational pension system in 1985 (Gabriel et al., 2015). Both programmes aimed to secure material security in old age through the constitution of a life course financial reserve accumulated across one’s working life. Since women’s professional trajectories were much shorter, interrupted and part-time compared to men, this system made married women highly dependent on their husband’s incomes (Oris et al., 2017).

Globally, such processes created what Levy and Widmer (2013) have rightly called gendered life courses, with a differential accumulation of reserves to face old age. Striking intercohort differences in available income were another result of the aforementioned dynamics. In the wealthy country of Switzerland, income poverty affected 51% of residents aged 65+ in 1979, but this proportion had decreased to 21% by 2011/12 (Gabriel et al., 2015). Although the gender gap declined after 1979, in 2011/12, women were still clearly more often poor, as were members of the older cohorts (born before 1926). A series of analyses revealed that those disadvantages in old age are accounted for by the level of education (Gabriel et al., 2015; Oris et al., 2017). For the elderly who were studied both in 1979 and in 2011, a low level of education multiplied the risk of income-poverty in old age by a factor of 2.5 compared to an average level of education, indicating that most of the social inequalities in early life are transferred into old age. This trait is common in so-called Bismarckian (conservative) welfare states (see Esping-Andersen, 1990; van der Linden et al., 2020). Accordingly, the historical expansion of education was the main driver of the decrease in old age poverty and of upward social mobility, two processes that were crucial for the improved accumulation of economic reserves across cohorts (Oris et al., 2017).

Matching those empirical results with theoretical explanations, the long-term influence of early life conditions on old age reserves is clear. Our results strengthen the international consensus regarding this point (Oris et al., 2021). According to the theory of cumulative (dis)advantage, early interindividual differences should increase over time, at least until old age (Spini et al., 2017; Spini & Widmer, 2022). Nonetheless, while according to Dale Dannefer (2020, p. 1), ‘Over recent decades, evidence supporting cumulative dis/advantage (CDA) as a cohort-based process that produces inequalities on a range of life-course outcomes has steadily increased’, we join Glen Elder and his colleagues (2015, p. 23) in being more sceptical about CDA. Our research on Switzerland has suggested that the accumulation of disadvantages and the accumulation of advantages are not symmetric. Indeed, the welfare regime has limited the triggering processes associated with low education (Oris et al., 2021). A modest safety net prevented the elderly from falling into precarity and instead resulted in a low-level ‘cumulative continuity’ (Elder et al., 2015, p. 23). Conversely, those with a middle or high education level had much better life chances later on. Such results support the approach of scholars who have investigated ‘how welfare states shape age-graded life courses and, next to social classes, generate “welfare classes” of life-stage specific benefit recipients, including retirees, children or widowed’ (Fasang & Mayer, 2020, p. 23). From that perspective, the Swiss welfare regime combines elements of the conservative model—especially for occupational insurance, which has been built on the male breadwinner model—and of the liberal model, particularly in the central role of individual responsibility and the prioritisation of private initiatives over state interventions (Baeriswyl et al., 2021). Such a structure is why older adults’ personal networks of support are crucial reserves for dealing with ageing in the Swiss context.

Such networks include groups of kin, of which the size and composition naturally depend on past family life (Widmer, 2016). As a result of the dynamics previously discussed and of the spectacular rise of longevity, the verticalisation of structures of kinship observed everywhere in Europe is reflected in the personal networks of people aged 65+ living in Switzerland; this is especially demonstrated by the increase, from 1979 until 2011, of those who have children and grandchildren as well as a living partner (Baeriswyl, 2016, p. 114). However, these structural changes do not tell us much about how people actually pursue relationships. In a series of VLV papers, ‘family’ was defined by older adults who identified themselves their most relevant connections. Six types of family networks were identified, with an unequal emphasis on partners, children, siblings, blood relatives, and friends, indicating that older adults develop a diversity of family networks beyond spouses and children. Approximately one in five respondents appeared to have no or very few significant family members (Girardin & Widmer, 2015).

While the discourse on postmodern societies has frequently assumed a decline in ascribed family ties and a growth of elective ties, it appears that among older adults, having a close friend represents a relational reserve that grew between 1979 and 2011 while not competing with family relationships (Baeriswyl & Oris, 2021). The increasing presence of close friends in the personal networks of the elderly from 1979 to 2011 was part of a broader lifestyle change observable after retirement that involved increasing social engagement (see below). Such change particularly benefited educated older adults (Baeriswyl, 2016). These results on both family networks and friendship supported our initial hypothesis that intercohort progress drastically changes the composition of the retiree population, with a majority of active, healthy older adults contrasting with a minority of vulnerable individuals who accumulate penalties (Oris, 2020).

Uses of Accumulated Reserves and Their Depletion in Old Age

This uneven distribution of a variety of reserves is crucial to understanding how older adults face the many challenges of life after retirement, a period of life that has been greatly extended in all wealthy countries in recent decades; in Switzerland in 2018/19, life expectancy at 65 reached 20 years for males and 22.7 for females (Oris, 2020). The growing gap between biological ageing and the institutional threshold defining old age explains the development, from the 1980s onwards, of influential international models that associated successful ageing with active ageing, viewing activity as a source of health and well-being (Bülow & Söderqvist, 2014). These discourses resonated with the rise of social participation (broadly defined as an individual’s activities involving interaction with others) and with the emergence of a lifestyle oriented towards social life beyond the household (Ang, 2019). In Switzerland, the number of social participations of home-dwelling older adults rose from 3.4 in 1979 to 4.3 in 2011. Only a small minority developed no social participation at all and appeared truly excluded from social life (5% in 1979, 3% in 2011) (Baeriswyl, 2017). Although the difference between women and men shrank between 1979 and 2011, gendered life courses continued to be reflected in men’s tendency to be more present in the public sphere compared to women’s higher involvement in private relations. Moreover, women need higher educational reserves than men to access similar levels of public engagement and even more to reach positions of power (Baeriswyl, 2018). In regard to life satisfaction, there is evidence for the importance of multiple types of participation, with some types being particularly meaningful: involvement in an association, visiting family or friends and church attendance. Multiple types of participation, associative involvement and friendship are more frequent among the upper social strata. In contrast, family and religious participation—which may be regarded as traditional modes of integration—have emerged as important practices for those with greater exposure to risks and stresses because they have fewer reserves, for instance, in terms of health and income. This is especially the case for less-educated older adults and for very old women (Baeriswyl, 2018; Oris et al., 2017).

Several LIVES empirical studies have demonstrated that models of active ageing are implicitly class-driven and gender-blind (Oris, 2020). Social class and gender are crucial since they impact not only economic and social reserves but also how family reserves are used to preserve intergenerational relationships. Older parents use their own financial reserves to help their children during the transition to adulthood (which has become more challenging than their own experience) or when their children face life accidents (which, again, is more frequent than in previous generations) (Widmer & Ritschard, 2009). Older parents’ propensity to provide financial support primarily depends on their wealth, thus leading to increasing social inequalities. Monetary transfers are also associated with relational reserves, particularly regarding the frequency of exchange of practical help within the family for men and for women with the position and the role they play within their family configuration (Baeriswyl et al., 2021). Distinct family configurations are associated with a variety of relational reserves with various issues for individuals. Relational reserves featuring a large density of interactions increase the family protection of older adults in need (Girardin & Widmer, 2015). As long as they can, and within the limits of their various and unequal economic and health reserves, older adults actively shape their relational reserves in ways that help them avoid conflict and stress to increase their positive interactions with others (Girardin et al., 2018; Widmer et al., 2018).

While socioeconomic inequalities differentiate individual positions in social circles and personal networks, old age does not appear to level out social inequality (Fasang & Mayer, 2020, p. 25). Instead, the accumulation of disadvantages, which, as we have seen above, was not obvious during their adulthood, emerged in our sample of older adults and exacerbated the long-term impact of early-life conditions and intergenerational reproduction. The follow-up of the VLV survey in 2017, six years after the first wave, showed considerable volatility in old-age poverty. In 2011, blue-collar workers were at greater risk of being income-poor and of feeling poor (subjective assessment), but they were also more prone to falling into poverty while ageing (becoming income-poor and beginning to have difficulties in making ends meet) (Gabriel et al., 2021). Blue-collar life after retirement appeared to be marked by the depletion of their limited financial reserves, with limited capacities to rebuild them. Such economic inequalities translate into life expectancy differentials. Drawing on a national database that links population censuses, death certificates, and Swiss Health Surveys, (Remund et al., 2019) showed that in Switzerland, a country that competes with Japan for the highest life expectancy in the world, life expectancy in good health of those with low educational attainment has been stagnating since 2000, resulting in an expansion of their morbidity.

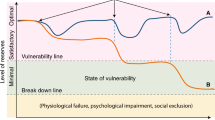

The concept of frailty, however, bridges the perspectives of social and medical sciences on ageing more fruitfully than morbidity. As a phenotype, frailty expresses a decrease in functional ability that makes it difficult to manage daily activities and social interactions, threatening but not abolishing autonomy. With the expansion of longevity, the prevalence of frailty has grown during recent decades and has become part of a large majority of the oldest people’s ageing trajectories (Spini et al., 2007). In Switzerland, the VLV survey showed that among those aged 80+, 28% of the women were independent, 48% were frail, and 24% were dependent; among men, those figures were 42%, 41% and 17%, respectively (Tholomier, 2017). Frailty is an illustration of ‘the lack of reserves [which] is synonymous of vulnerability, when decreasing reserves meet a threshold, which may be defined as individuals being unable to restore a normal state of agency in the pursuit of their life’ (Cullati et al., 2018).

If vulnerability of the frail elderly is obvious when their survival is threatened during heat waves or the COVID-19 pandemic (Oris et al., 2020), in normal times, their mastery of life is shaped—either favoured or hindered—by institutional and social support systems and by a complex network of actors within a policy framework that encourages the elderly to stay at home (Masotti, 2018). Staying at home is important for many older adults since the ability to preserve one’s personal identity and personal networks in old age can be challenging. Even when professional caregivers step into their private sphere, older adults use all their remaining reserves. They struggle to preserve a sense of control over their lives, bargain their care trajectories, cope with constraints to preserve acceptable living conditions, and contest situations when they do not obtain what they believe is right (Masotti, 2018). Other modes of coping with low and/or decreasing reserves and managing downward adaptations have been identified in research on the subjective experience of economic vulnerability in old age. Julia Henke’s results have supported the idea that ‘older adults increasingly see finances as a means to an end rather that an end in itself and that their judgement of financial adequacy may be more strongly influenced by questions of adequacy and a fair and just treatment than by objective resources’ (Henke, 2020, p. 305). Wisdom and stoicism are further reserves that have been built up throughout a life course marked by sociohistorical experiences shared across the same birth cohorts: those who faced economic crises in the 1920s and the 1930s and WWII. The memory of past is the basis for an intrabiographical referencing (Henke, 2020, p. 313) that Masotti (2018, p. 92) also observed in her interviews of care receivers, who did not want ‘to let themselves go’. As expected, these values are clearly more present among the oldest cohorts than among the younger cohorts.

This desire to maintain a sense of mastery over their lives plays a decisive role in the ability of the oldest old people to cope with declining reserves while maintaining their level of well-being. Among the 3080 individuals who were cognitively able to respond themselves to the VLV questionnaires, life satisfaction was high on average (between 26 and 28 on the Diener et al. (1985) scale, which has a maximum score of 35) and was similar for the young old and the oldest old (until age 90+). However, when also considering those VLV participants suffering from cognitive impairments, the picture is less rosy: Among the oldest old, there was an increase in difficulty with age, for example, in the ability to follow a conversation or in personal care (31% of women and 22% of men aged 80+), as well as a high prevalence of physical disorders and multimorbidity. As the norm of the autonomous individual largely dominates in Swiss society, when illnesses no longer allow people to control their lives or to take care of themselves, it is not surprising that depression arises (Tholomier, 2017). Some individuals then reach ‘thresholds [of reserves] below which functioning becomes highly challenging’ (Cullati et al., 2018, p. 551). Such results highlight the importance of data collection, such as VLV, that meets the challenge of including the most vulnerable.

Conclusion

The story of the Swiss birth cohorts 1911–1946 is largely similar to that of other Western Europeans from the same generations. The development of reserves and their use and depletion were embedded in multidimensional lives in which family, social relations and participations and professional careers interacted to create relatively standardised and clearly gendered life courses. Switzerland’s uniqueness is the result of a mixture of a conservative and a liberal ethos that has structured the historical developments of education and the welfare regime. Both have strongly impacted the individual life courses of men and women, leading to predominantly stable social trajectories from childhood to old age. The influence of the school system has been decisive, since inequalities early in life are still clearly present half a century later in postretirement life. Such inequalities have affected both the availability of reserves and their preservation, with older adults with low education being more often poor and more at risk of becoming poor while ageing. Alternatively, in a context of economic growth, the extension of the available education has impressively transformed cohort composition, individual life chances and the sociohistorical development of reserves. Health and living conditions have improved, and gender inequalities have decreased. Such progress has supported the growth of social participation, a more active citizen life, and an increase in relational reserves, although within the context of diversification of the family configurations. Nevertheless, in Switzerland, one of the wealthiest countries in the world, one in five older adults are still affected by poverty; the same proportion has no personal network; and frailty, multimorbidity or depression are highly prevalent among the oldest old. Old-age vulnerabilities remain a crucial issue for social cohesion and citizenship.

References

Allmendinger, J., & Leibfried, S. (2003). Education and the welfare state: The four worlds of competence production. Journal of European Social Policy, 13(1), 63–81.

Ang, S. (2019). Life course social connectedness: Age-cohort trends in social participation. Advances in Life Course Research, 39, 13–22.

Baeriswyl, M. (2016). Participations et rôles sociaux à l’âge de la retraite: Une analyse des évolutions et enjeux autour de la participation sociale et des rapports sociaux de sexe, PhD, University of Geneva.

Baeriswyl, M. (2017). Participations sociales au temps de la retraite. Une approche des inégalités et évolutions dans la vieillesse. In N. Burnay & C. Hummel (Eds.), L’impensé des classes sociales dans le processus de vieillissement (pp. 141–170). Peter Lang.

Baeriswyl, M. (2018). L’engagement collectif des aînés au prisme du genre: Evolutions et enjeux. Gérontologie et société, 40/157(3), 53–78.

Baeriswyl, M., Girardin, M., & Oris, M. (2021). Financial support given by older adults to family members. A configurational perspective. Journal of Demographic Economics. https://doi.org/10.1017/dem.2021.21

Baeriswyl, M., & Oris, M. (2021). Social participation and life satisfaction among older adults: Diversity of practices and social inequality in Switzerland. Ageing & Society, 1–25.

Bülow, M. H., & Söderqvist, T. (2014). Successful ageing: A historical overview and critical analysis of a successful concept. Journal of Aging Studies, 31, 139–149.

Cullati, S., Kliegel, M., & Widmer, E. D. (2018). Development of reserves over the life course and onset of vulnerability in later life. Nature Human Behaviour, 2, 551–558.

Dannefer, D. (2020). Systemic and reflexive: Foundations of cumulative dis/advantage and life-course processes. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 75(6), 1249–1263.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75.

Duvoisin, A. (2020). Les origines du baby-boom en Suisse au prisme des parcours féminins. Peter Lang.

Duvoisin, A., & Oris, M. (2019). Une approche biographique mixte pour renouveler l’étude du baby-boom. Cahiers québécois de Démographie, 48(1), 83–106.

Elder, G. H., Shanahan, M. J., & Jennings, J. A. (2015). Human development in time and place. In R. M. Lerhner (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science (pp. 6–54). Wiley.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton University Press.

Fasang, A., & Mayer, K. U. (2020). Lifecourse and social inequality. In J. Falkingham, M. Evandrou, & A. Vlachantoni (Eds.), Handbook on demographic change and the lifecourse (pp. 22–39). Elgar.

Gabriel, R., Oris, M., Kubat, S., Adili, K., & Götzö, M. (2021). Between social stratification and critical life events: The role of work before and after retirement on poverty dynamics in old age. In C. Suter, J. Cuvi, P. Balsiger, & M. Nedelcu (Eds.), The Future of Work (pp. 171–198). Zurich.

Gabriel, R., Oris, M., Studer, M., & Baeriswyl, M. (2015). The persistence of social stratification? A life course perspective on old-age poverty in Switzerland, Swiss. Journal of Sociology, 41(3), 465–487.

Girardin, M., & Widmer, E. (2015). Lay definitions of family and social capital in later life. Personal Relationships, 22, 712–737.

Girardin, M., Widmer, E. D., Connidis, I. A., Castrén, A.-M., Gouveia, R., & Masotti, B. (2018). Ambivalence in later-life family networks: Beyond intergenerational dyads. Journal of Marriage and Family, 80, 768–784.

Henke, J. (2020). Revisiting economic vulnerability in old age. Low income and subjective experiences among Swiss pensioners. Springer.

Ihle, A., Rimmele, U., Oris, M., Maurer, J., & Kliegel, M. (2020). The longitudinal relationship of perceived stress predicting subsequent decline in executive functioning in old age is attenuated in individuals with greater cognitive reserve. Gerontology, 66(1), 65–73.

Kohli, M. (2007). The institutionalization of the life course: Looking back to look ahead. Research in Human Development, 4, 253–271.

Levy, R., & Bühlmann, F. (2016). Towards a socio-structural framework for life course analysis. Advances in Life Course Research, 30, 30–42.

Levy, R., & Widmer, E. D. (Eds.). (2013). Gendered life courses between standardization and individualization. A European approach applied to Switzerland. Lit Verlag.

Masotti, B. (2018). Demander (ou pas) l’aide à domicile au grand âge. L’agency des personnes âgées. Gérontologie et société, 40, 79–95.

Morselli, D., Dasoki, N., Gabriel, R., Gauthier, J.-A., Henke, J., & Le Goff, J.-M. (2016). Using life history calendars to survey vulnerability. In M. Oris, C. Roberts, D. Joye, & M. Ernst-Stähli (Eds.), Surveying human vulnerabilities across the life course (pp. 179–201). Springer.

Oris, M., Baeriswyl, M., & Ihle, A. (2021). The life course construction of inequalities in health and wealth in old age. In F. Rojo-Perez & G. Fernandez-Mayoralas (Eds.), Handbook of active ageing and quality of life. From concepts to applications (pp. 97–109). Springer.

Oris, M., Gabriel, R., Ritschard, G., & Kliegel, M. (2017). Long lives and old age poverty. Social stratification and life Course institutionalization in Switzerland. Research in Human Development, 14(1), 68–87.

Oris, M., Guichard, E., Nicolet, M., Gabriel, R., Tholomier, A., Monnot, C., Fagot, D., & Joye, D. (2016). Representation of vulnerability and the elderly. A Total Survey Error perspective on the VLV survey. In M. Oris, C. Roberts, D. Joye, & M. Ernst-Stähli (Eds.), Surveying human vulnerabilities across the life course (pp. 27–64). Springer.

Oris, M., Ramiro Farinas, D., Pujol Rodriguez, R. & Abellán García, A. (2020). La crise comme révélateur de la position sociale des personnes âgées – la Suisse et l’Espagne, In F. Gamba, M. Nardone, T. Ricciardi, S. Cattacin (éds.), COVID-19. Le regard des sciences sociales, Seismo, 179–191.

Oris, M. (2020). Vieillissement démographique et bien-être des aînés. Progrès et inégalités. Bulletin de l’Académie Suisse des Sciences Humaines et Sociales, 2, 32–35.

Remund, A., Cullati, S., Sieber, S., Burton-Jeangros, C., & Oris, M. (2019). Longer and healthier lives for all? Successes and failures of a universal consumer-driven health care system. International Journal of Public Health, 64(8), 1173–1181.

Spini, D., Bernardi, L., & Oris, M. (2017). Towards a life course framework for studying vulnerability. Research in Human Development, 14, 5–24.

Spini, D., Ghisletta, P., Guilley, E., & Lalive d’Epinay, C. (2007). Frail Elderly. In J. E. Birren (Ed.), Encyclopedia of gerontology (pp. 572–579). Elsevier.

Spini, D., & Jopp, D. (2014). Old age and its challenges to identity. In R. Jaspal & G. Breakwell (Eds.), Identity process theory: Identity, social action and social change (pp. 295–315). Cambridge University Press.

Spini, D., & Widmer, E. (2022). Inhabiting vulnerability throughout the life course. In this volume.

Tholomier, A. (2017). Vivre et survivre au grand âge: enjeux des inégalités sociales et de santé au sein des générations qui ont traversé le 20ème siècle. PhD, University of Geneva.

van der Linden, B. W., Sieber, S., Cheval, B., Orsholits, D., Guessous, I., Gabriel, R., von Arx, M., Kelly-Irving, M., Aartsen, M., Blane, D., Boisgontier, M. P., Courvoisier, D., Oris, M., Kliegel, M., & Cullati, S. (2020). Life-course circumstances and frailty in old age within different European welfare regimes: A longitudinal study with SHARE. The Journals of Gerontology Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 75(6), 1312–1325.

Widmer, E. D. (2016). Family configurations: A structural approach to family diversity. Routledge.

Widmer, E. D., Girardin, M., & Ludwig, C. (2018). Conflict structures in family networks of older adults and their relationship with health-related quality of life. Journal of Family Issues, 39(6), 1573–1597.

Widmer, E. D., & Ritschard, G. (2009). The de-standardization of the life course: Are men and women equal? Advances in Life Course Research, 14(1–2), 28–39.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Oris, M. et al. (2023). On the Sociohistorical Construction of Social and Economic Reserves Across the Life Course and on Their Use in Old Age. In: Spini, D., Widmer, E. (eds) Withstanding Vulnerability throughout Adult Life. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-4567-0_17

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-4567-0_17

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-19-4566-3

Online ISBN: 978-981-19-4567-0

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)