Abstract

Cholinergic neurotransmission plays a critical role in neuronal plasticity and cell survival in the central nervous system (CNS). Two types of acetylcholine receptors (AChRs), muscarinic AChRs (mAChRs) and nicotinic AChRs (nAChRs), trigger intracellular signaling through G protein activity and ion influx, respectively. To assess mechanisms underlying neuroprotection through nAChRs, we developed SAK3, a novel modulator of nAChR activity. Recently, we found that SAK3 enhances T-type calcium channel activity, promoting ACh release in the hippocampal CA1 region of olfactory-bulbectomized mice. Here, we observed potent SAK3 neuroprotective activity in mice with 20-min bilateral common carotid artery occlusion (BCCAO) or hypothyroidism. Treatment of mice with the α7 nAChR-selective inhibitor methyllycaconitine (0.5 mg/kg/day, p.o.) antagonized SAK3-mediated neuroprotection and memory improvement in BCCAO mice. Single administration of the anti-Graves’ disease therapeutic methimazole (MMI) to female mice disrupted olfactory bulb (OB) glomerular structure, and cholinergic neurons largely disappeared in the medial septum followed by memory loss. Chronic SAK3 (0.5–1 mg/kg, p.o.) administration significantly rescued the number of cholinergic medial septum neurons in MMI-treated mice and improved cognitive deficits seen in those mice. Overall, our study suggests that, in mice, the novel nAChR modulator SAK3 can rescue neurons impaired by transient ischemia and hypothyroidism. We also address mechanisms common to SAK3-induced neuroprotection in both conditions.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- T-type calcium channel

- Neuroprotection

- Ischemia

- Hypothyroidism

- Methimazole

- Memory

- Alzheimer’s disease

9.1 Introduction

Acetylcholine (ACh) is a major neurotransmitter in the central nervous system (CNS) and transduces signals via two types of ACh receptors (AChRs): muscarinic (mAChRs) and nicotinic (nAChRs). While mAChRs are G-protein-coupled, nAChRs are ligand-gated cation channels consisting of five subunits (Zdanowski et al. 2015). Both AChR pathways function in learning and memory (Melancon et al. 2013; Pandya and Yakel 2013) and play a critical role in cell survival in in vitro and in vivo models (Akaike et al. 2010; Tan et al. 2014; Zdanowski et al. 2015). Drugs that enhance ACh concentration in the CNS, including the acetylcholine esterase (AChE) inhibitors donepezil, galantamine and rivastigmine, are among widely used therapeutics used to treat early stage Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). However, it remains unclear whether the effects of AChE inhibitors are mediated by nAChRs or mAChRs in human brain. We recently developed the lead compound of the AD therapeutic SAK3 (ethyl 8′-methyl-2′,4-dioxo-2-(piperidin-1-yl)-2′H-spiro[cyclopentane-1,3′-imidazo[1,2 a]pyridin] -2-ene-3-carboxylate) (Yabuki et al. 2017a, b). SAK3 primarily stimulates T-type voltage gated Ca2+ channels in brain, and importantly it enhances ACh release in hippocampus, thereby improving memory in olfactory-bulbectomized (OBX) mice. We found that SAK3 effects on ACh release and memory improvement were antagonized by nAChR inhibitors, suggesting that SAK3 modulates nAChR. This review focuses primarily on SAK3 neuroprotective activity mediated by nicotinic cholinergic pathways.

9.2 Neuroprotection Mediated by mAChRs

Subchronic treatment with the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor galantamine (3.5 mg/kg, i.p.) prevents cell death and axonal injury after ocular hypertension surgery in rat retinal ganglion cells (RGCs), an effect blocked by the non-selective mAChR antagonist scopolamine, the M1-type mAChR antagonist pirenzepine, or the M4-type mAChR antagonist tropicamide, but not by nAChR inhibitors (Almasieh et al. 2010). In agreement with these results, the M1-type mAChR agonist pilocarpine protects RGCs from glutamate-induced neurotoxicity and ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat primary retinal cultures and in rat retina (Tan et al. 2014). M1-type mAChR activation in PC12 cells promotes protein kinase C (PKC) activity and inhibits glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) activity, thereby increasing levels of NF-E2-related factor-2 (Nrf2) protein, which regulates transcription of the gene encoding the anti-oxidant protein hemeoxygenase I (HO-1) (Espada et al. 2009; Ma et al. 2013). Therefore, activation of that anti-oxidant pathway through Nrf2 stimulation likely underlies mAChR-dependent neuroprotection. Likewise, the M1-type mAChR-selective agonist AF267B rescues rat primary hippocampal neurons exposed to amyloid-β (Aβ) from cell death by inhibiting increases in GSK-3β (Farías et al. 2004). On the other hand, the mAChR antagonist scopolamine does not block neuroprotection by acetylcholinesterase inhibitors on glutamate (1 mM) toxicity in primary rat cortical neurons (Takada-Takatori et al. 2009). Thus, how mAChRs promote neuroprotection is not entirely clear.

9.3 Neuroprotective Action Mediated by nAChRs

Nine different nAChR subunits (α2-7 and β2-4) are expressed in mammalian brain, and in mouse brain major nAChRs are comprised of homomeric α7 AChR and heteromeric α4β2 complexes (Dani and Bertrand 2007; Dineley et al. 2015; Yakel 2013). Many studies in cultured neurons support the idea that nAChRs have neuroprotective effects. For example, nicotine (10 μM) treatment protects cultured rat primary cortical neurons from cell death by glutamate (1 mM) exposure by activating α4β2 and α7 nAChRs (Kaneko et al. 1997). In addition, the α4β2 inhibitor dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE) and α7 inhibitor methyllycaconitine (MLA) both block neuroprotective effects of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors on glutamate (1 mM)-induced excitotoxicity in cultured neurons, an effect not seen following treatment of cells with the mAChR antagonist scopolamine (Takada-Takatori et al. 2009). In vivo, galantamine treatment prevents death of gerbil hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons following transient bilateral common carotid artery occlusion (BCCAO), an effect blocked by the non-selective nAChR inhibitor mecamylamine (MEC) (Lorrio et al. 2007). Combined neostigmine and anisodamine treatment are neuroprotective against middle cerebral artery occlusion in wild type- but not in α7 nAChR knock-out mice (Qian et al. 2015). We recently observed that the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor donepezil antagonizes loss of cholinergic neurons in the medial septum (MS) of OBX mice through nAChR stimulation (Yamamoto and Fuknaga 2013). In addition, Hijioka et al. (2012) reported that the α7-specific agonist PNU-282987 but not the α4-specific agonist RJR-2403 blocks neuronal loss following intracerebral hemorrhage in mouse striatum. Since MEC, DHβE and MLA do not block neuroprotective effects of galantamine following ocular hypertension surgery in rat RGCs, neuroprotection mediated by nAChRs may play a more predominant role in CNS than in peripheral neurons. We previously reported that galantamine stimulates glutamatergic and GABAnergic synaptic transmission via nAChR stimulation in rat cortical neurons (Moriguchi et al. 2009). Interestingly, galantamine increases hippocampal insulin-like growth factor 2 expression via the α7 nAChR in mice (Kita et al. 2013). Similarly, stimulation of α7 by the selective agonist PHA-543613 or galantamine treatment enhances α7 channel activity and improves Aβ-induced cognitive deficits in mice (Sadigh-Eteghad et al. 2015). In addition, galantamine treatment promotes survival of newborn neurons in the hippocampal dentate gyrus (DG) viaα7 nAChR but not via M1 mAChR activity (Kita et al. 2014). Taken together, the neuroprotective effect of galantamine is mediated both by mAChRs and nAChRs in the CNS.

9.4 Development of the Novel nAChR Modulator SAK3

T-type calcium channels, which are encoded by the CACNA1G (Cav3.1), CACNA1H (Cav3.2) and CACNA1I (Cav3.3), are voltage-gated calcium channels that give rise to low-threshold calcium spikes, which in turn trigger burst firing mediated by sodium channels in many neurons (Huguenard 1996; Perez-Reyes 2003). Recently, we found that a novel AD therapeutic candidate, ST101 (spiro[imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine-3,2-indan]-2(3H)-one), increases Cav3.1 T-type calcium channel currents (Moriguchi et al. 2012). ST101 accelerated ACh release in the hippocampus of OBX mice, an effect inhibited by the T-type calcium channel blocker mibefradil and by nAChR inhibitors (Yamamoto et al. 2013). Moreover, intraventricular injection of mecamylamine inhibited ST101-elicited neurogenesis in the hippocampal DG of OBX mice (Shioda et al. 2010), suggesting that ST101 may activate nAChR and promote ACh release. However, clinical trials showed that administration of ST101 alone was not sufficient to improve memory deficits in AD patients (Gauthier et al. 2015). Therefore, we sought a more potent Cav3.1 and Cav3.3 T-type calcium channel enhancer, resulting in development of SAK3 (Yabuki et al. 2017b). We found that SAK3 promoted more potent ACh release in mouse hippocampal CA1 than did ST101 (Yabuki et al. 2017b).

9.5 SAK3-Induced Neuroprotection in Brain Ischemia

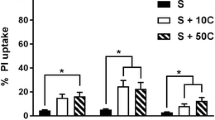

We confirmed SAK3 neuroprotection using a 20-min BCCAO mouse model. To do so, we administered SAK3 (at 0.1, 0.5 or 1.0 mg/kg, p.o.) orally to mice 24 h after BCCAO ischemia. SAK3 administration at 0.5 or 1.0 mg/kg/day significantly blocked loss of hippocampal CA1 neurons and memory deficits seen in BCCAO mice. Treatment with the α7 nAChR-selective inhibitor methyllycaconitine (MLA: 6.0 mg/kg/day, i.p.) antagonized both neuroprotection and memory improvement seen in SAK3 (0.5 mg/kg/day, p.o.)-treated mice (Fig. 9.1). Since excess calcium influx enhances excitotoxic and proapoptotic pathways to induce ischemic neuronal death (Berliocchi et al. 2005; Bano and Nicotera 2007), the impact of T-type channel regulators on neuroprotection is unclear. For example, intraventricular injection of mibefradil and pimozide 6 h before 10-min BCCAO ischemia antagonizes hippocampal injury in rats (Bancila et al. 2011). Other T-type calcium channel blockers, such as U-92032 and flunarizine, administered 1 h prior to BCCAO inhibit delayed neuronal death in the gerbil hippocampal CA1 region (Ito et al. 1994). Such varied effects of T-type calcium channel blockers may be due to differences in timing of drug administration. We administered SAK3 to animals 24 h after BCCAO, whereas others have administered T-type calcium channel blockers before brain ischemia (Bancila et al. 2011; Ito et al. 1994). Moreover, some T-type calcium channel inhibitors, such as mibefradil and flunarizine have affinities to other channel types such as L-type calcium, sodium or potassium channels (Liu et al. 1999; Bloc et al. 2000; McNulty and Hanck 2004). Therefore, SAK3 is neuroprotective against brain ischemia by a mechanism that differs from that of other drugs.

Oral SAK3 administration antagonizes loss of CA1 neurons after BCCAO through α7 nAChR stimulation. (a) Representative histological sections of hippocampus in control, vehicle-administered BCCAO, SAK3 (0.1, 0.5 or 1.0 mg/kg, p.o.)-administered BCCAO mice or SAK3 (0.5 mg/kg, p.o.)-administered BCCAO mice treated with MLA. Mice were sacrificed 11 days after BCCAO for histopathological analysis. Scale bars: low magnification, 500 μm; high magnification, 100 μm. (b) Cell viability is expressed as a percent of the average number of viable hippocampal CA1 cells from control mice (n = 12–23 per group). Error bars represent SEM. ** p < 0.01 vs. control mice. ## p < 0.01 vs. vehicle-administered BCCAO mice. †† p < 0.01 vs. SAK3 (0.5 mg/kg, p.o.)-administered BCCAO mice. MLA, methllycaconitine (6.0 mg/kg, i.p.) treatment; SAK3 (0.1), SAK3 (0.1 mg/kg, p.o.) administration; SAK3 (0.5), SAK3 (0.5 mg/kg, p.o.) administration; SAK3 (1.0), SAK3 (1.0 mg/kg, p.o.) administration; and Veh, vehicle administration. (Modified from Yabuki et al. 2017a)

9.6 SAK3 Ameliorates Methimazole-Induced Cholinergic Neuronal Damage

The drug methimazole (MMI) is widely used to antagonize hyperthyroidism and manage Graves’ disease, an autoimmune condition promoting hyperthyroidism (Cano-Europa et al. 2011; Wu et al. 2013). Biochemically, MMI acts by preventing iodine incorporation into the thyroid hormone precursor, thyroglobulin, and thus interferes with conversion of thyroxine (T4) to triiodothyronine (T3) (Cooper 1984; Amara et al. 2012; Parisa and Fahimeh 2015). Importantly, treatment with moderate doses of MMI reportedly impairs olfactory function in rats, while high doses cause complete destruction of the olfactory epithelium (OE) (Genter et al. 1995). The OE is a critical site of regeneration of physically- or chemically-injured olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs) (Schwob et al. 1992; Suzukawa et al. 2011). Thyroid hormone deficiency also causes significantly reduced levels of choline acetyltransferase (ChAT), a marker of cholinergic neurons, in various brain regions (Kojima et al. 1981; Oh et al. 1991; Sawin et al. 1998). Since cholinergic neurons in the MS innervate the olfactory bulb and hippocampus (Mesulam et al. 1983a), olfactory bulbectomy leads to anterograde degeneration of MS cholinergic neurons and concomitant loss of hippocampal cholinergic nerve terminals (Han et al. 2008). Loss of MS cholinergic neurons is also associated with cognitive deficits seen in Alzheimer’s disease (Robinson et al. 2011). Indeed, single administration of MMI (75 mg/kg, i.p.) promotes hypothyroidism in mice, and SAK3 treatment prevents hypothyroidism-induced loss of MS cholinergic neurons, thereby improving memory deficits seen in MMI-treated mice (Noreen et al. 2017). In humans, adult onset hypothyroidism is associated with impaired spatial memory performance and cognitive function (Tong et al. 2007; Artis et al. 2012), although mechanisms underlying these impairments remain unclear.

Our recent analysis of MMI-treated mice showed that SAK3 may be neuroprotective and antagonize these cognitive deficits (Fig. 9.2). We found that perturbation of OSN maturation by a single dose of MMI is accompanied by a decrease in the number of MS cholinergic neurons (Fig. 9.3), a loss that likely causes memory and cognitive deficits seen in these mice. Importantly, SAK3 administration to MMI-treated mice rescued degeneration of MS cholinergic neurons and improved deficits in spatial reference memory and cognition.

MMI-induced decreases in OMP expression in olfactory bulb glomeruli are antagonized by SAK3 administration. (a) Coronal sections of olfactory bulb from indicated control (c), MMI-treated, or MMI-treated and SAK3-treated (0.1, 0.5 and 1 mg/kg) mice were incubated with OMP antibody. (b) SAK3 treatment significantly restored OMP staining intensity (b) and increased glomerulus size (c) in the OB glomerular layer. Scale bar, 50 μm. Error bars represent S.E.M. (**p < 0.01 vs control, #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs MMI). n = 7 per group. (Modified from Noreen et al. 2017)

SAK3 administration rescues MMI-induced decreases in the number of ChAT-positive cells in the medial septum. Photomicrographs showing anti-ChAT staining in the medial septum (MS) area. (b) ChAT-positive cells were counted in the MS of control or MMI-treated mice with or without SAK3 administration (0.1, 0.5 and 1 mg/kg). Scale bar, 100 μm. Error bars represent S.E.M. (**p < 0.01 vs control, #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs MMI). n = 7 per group. (Modified from Noreen et al. 2017)

9.7 SAK3 Is Neuroprotective Via nAChRs

Several reports indicate that nAChR neuroprotective activity requires activation of protein kinase B (Akt) signaling, a critical cell survival pathway (Davis and Pennypacker 2016; Fan et al. 2017). The α7 but not the α4 nAChR subunit interacts with the non-receptor-type tyrosine kinase Fyn and janus-activated kinase 2 (JAK2) (Kihara et al. 2001; Shaw et al. 2002), and α7 nAChR stimulation triggers activation of both kinases and subsequently upregulates phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K) (Kihara et al. 2001; Shaw et al. 2002). Activated PI3K in turn promotes Akt activity and downstream survival signaling, including Nrf2/HO-1 signaling in neurons (Franke et al. 1997; Kihara et al. 2001; Navarro et al. 2015; Niture and Jaiswal 2012; Shaw et al. 2002). By contrast, α7 nAChR activation in microglia and/or astrocytes is neuroprotective by promoting release of anti-inflammatory cytokines and blocking release of inflammatory cytokines (Di Cesare et al. 2015; Shin and Dixon 2015). The observation that both SAK3-induced ACh release and SAK3-induced neuroprotection are blocked by α7 nAChR inhibitors supports the idea that SAK3 effects are in large part mediated by nAChRs. SAK3-induced neuroprotection is closely associated with enhanced Akt rather than ERK activities (Yabuki et al. 2017a, b) (Fig. 9.4). In this context, α7 nAChR activation by SAK3 administration is critical for neuroprotection.

Acute SAK3 administration rescues Akt phosphorylation in CA1 pyramidal neurons of BCCAO mice through α7 nAChR stimulation. (a) Representative images showing fluorescent immunostaining with phospho-Akt (Ser-473: green) and NeuN (red) antibodies. Phosphorylated Akt immunoreactivity decreased in CA1 NeuN-positive neurons 24 h after BCCAO. Treatment with MLA (6.0 mg/kg, i.p.) blocked SAK3-dependent increases in Akt phosphorylation in NeuN-positive neurons. Scale bars: 20 μm. (b) Fluorescence intensity of Akt phosphorylation was measured in the hippocampal CA1 region. Immunofluorescence intensity of phosphorylated Akt significantly decreased in CA1 pyramidal cells (n = 4–5 per group). Error bars represent SEM. ** p < 0.01 vs. control mice. # P < 0.05 vs. vehicle-administered BCCAO mice. † p < 0.05 vs. SAK3 (0.5 mg/kg, p.o.)-administered BCCAO mice. MLA, methllycaconitine (6.0 mg/kg, i.p.) treatment; SAK3 (0.5), SAK3 (0.5 mg/kg, p.o.) administration; and Veh, vehicle administration. (Modified from Yabuki et al. 2017a)

9.8 Conclusion

Here, we have discussed neuroprotective activity of AChR signaling based on analysis of the novel modulator SAK3. SAK3 enhances activity of T-type calcium channels, promoting ACh release and activating hippocampal nAChRs, which are critical for memory formation. However, off-target analysis is required to determine whether SAK3 modulates nAChRs directly or indirectly. Since SAK3 activity in the CNS differs from that of cholinesterase inhibitors and from the nAChR modulator memantine, SAK3 is an attractive candidate to antagonize CNS neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s or Lewy body Diseases.

Disclosure/Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- Aβ:

-

Amyloid-β

- ACh:

-

Acetylcholine

- Akt:

-

Protein kinase B

- BCCAO:

-

Bilateral common carotid artery occlusion

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- DhβE:

-

Dihydro-β-erythroidine

- ERK:

-

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- HO-1:

-

Heme-oxygenase 1

- JAK2:

-

Janus-activated kinase 2

- MEC:

-

Mecamylamine

- MMI:

-

Methimazole

- MLA:

-

Methyllycaconitine

- mAChR:

-

Muscarinic ACh receptor

- nAChR:

-

Nicotinic ACh receptor

- OBX:

-

Olfactory-bulbectomized

- PI3K:

-

Phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase

- PKC:

-

Protein kinase C

- RGC:

-

Retinal ganglion cell

- SAK3:

-

Ethyl 8’-methyl-2’,4-dioxo-2- (piperidin-1-yl)-2’H-spiro[cyclopentane-1,3’-imidazo[1,2-a]pyridin]-2-ene-3-carboxylate

- ST101:

-

Spiro[imidazo[1,2-a] pyridine-3,2-indan]-2(3H)-one

References

Akaike A, Takada-Takatori Y, Kume T, Izumi Y (2010) Mechanisms of neuroprotective effects of nicotine and acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: role of alpha4 and alpha7 receptors in neuroprotection. J Mol Neurosci 40(1–2):211–216

Almasieh M, Zhou Y, Kelly ME, Casanova C, Di Polo A (2010) Structural and functional neuroprotection in glaucoma: role of galantamine-mediated activation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Cell Death Dis 1:e27

Amara IB, Troudi A, Soudani N, Guermazi F, Zeghal N (2012) Toxicity of methimazole on femoral bone in suckling rats: alleviation by selenium. Exp Toxicol Pathol 64:187–195

Artis AS, Bitiktas S, Taşkın E, Dolu N, Liman N, Suer C (2012) Experimental hypothyroidism delays field excitatory post-synaptic potentials and disrupts hippocampal long-term potentiation in the dentate gyrus of hippocampal formation and Y-maze performance in adult rats. J Neuroendocrinol 24:422–433

Bancila M, Copin JC, Daali Y, Schatlo B, Gasche Y, Bijlenga P (2011) Two structurally different T-type Ca2+ channel inhibitors, mibefradil and pimozide, protect CA1 neurons from delayed death after global ischemia in rats. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 25(4):469–478

Bano D, Nicotera P (2007) Ca2+ signals and neuronal death in brain ischemia. Stroke 38(2 Suppl):674–676

Berliocchi L, Bano D, Nicotera P (2005) Ca2+ signals and death programmes in neurons. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 360(1464):2255–2258

Bloc A, Cens T, Cruz H, Dunant Y (2000) Zinc-induced changes in ionic currents of clonal rat pancreatic -cells: activation of ATP-sensitive K+ channels. J Physiol 529(Pt 3):723–734

Cano-Europa E, Blas-Valdivia V, Franco-Colin M, Gallardo-Casa CA, Ortiz-Butron R (2011) Methimazole-induced hypothyroidism causes cellular damage in the spleen, heart, liver, lung and kidney. Acta Histochem 113:1–5

Cooper DS (1984) Antithyroid drugs. N Engl J Med 311:1353–1362

Dani JA, Bertrand D (2007) Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and nicotinic cholinergic mechanisms of the central nervous system. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 47:699–729

Davis SM, Pennypacker KR (2016) Targeting antioxidant enzyme expression as a therapeutic strategy for ischemic stroke. Neurochem Int 107:3–32. In press

Di Cesare Mannelli L, Tenci B, Zanardelli M, Failli P, Ghelardini C (2015) α7 nicotinic receptor promotes the neuroprotective functions of astrocytes against oxaliplatin neurotoxicity. Neural Plast 2015:396908

Dineley KT, Pandya AA, Yakel JL (2015) Nicotinic ACh receptors as therapeutic targets in CNS disorders. Trends Pharmacol Sci 36(2):96–108

Espada S, Rojo AI, Salinas M, Cuadrado A (2009) The muscarinic M1 receptor activates Nrf2 through a signaling cascade that involves protein kinase C and inhibition of GSK-3beta: connecting neurotransmission with neuroprotection. J Neurochem 110(3):1107–1119

Fan YY, Hu WW, Nan F, Chen Z (2017) Postconditioning-induced neuroprotection, mechanisms and applications in cerebral ischemia. Neurochem Int 107:43–56. In press

Farías GG, Godoy JA, Hernández F, Avila J, Fisher A, Inestrosa NC (2004) M1 muscarinic receptor activation protects neurons from beta-amyloid toxicity. A role for Wnt signaling pathway. Neurobiol Dis 17(2):337–348

Franke TF, Kaplan DR, Cantley LC (1997) PI3K: downstream AKTion blocks apoptosis. Cell 88:435–437

Gauthier S, Rountree S, Finn B, LaPlante B, Weber E, Oltersdorf T (2015) Effects of the acetylcholine release agents ST101 with donepezil in Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized phase 2 study. J Alzhemiers Dis 48(2):473–481

Genter MB, Deamer NJ, Blake BL, Wesley DS, Levi PE (1995) Olfactory toxicity of methimazole: dose–response and structure–activity studies and characterization of flavincontaining monooxygenase activity in the Long-Evans rat olfactory mucosa. Toxicol Pathol 23:477–486

Han F, Shioda N, Moriguchi S, Qin ZH, Fukunaga K (2008) The vanadium (IV) compound rescues septohippocampal cholinergic neurons from neurodegeneration in olfactory bulbectomized mice. Neuroscience 151:671–679

Hijioka M, Matsushita H, Ishibashi H, Hisatsune A, Isohama Y, Katsuki H (2012) α7 Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist attenuates neuropathological changes associated with intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. Neuroscience 222:10–19

Huguenard JR (1996) Low-threshold calcium currents in central nervous system neurons. Annu Rev Physiol 58:329–348

Ito C, Im WB, Takagi H, Takahashi M, Tsuzuki K, Liou SY, Kunihara M (1994) U-92032, a T-type Ca2+ channel blocker and antioxidant, reduces neuronal ischemic injuries. Eur J Pharmacol 257(3):203–210

Kaneko S, Maeda T, Kume T, Kochiyama H, Akaike A, Shimohama S, Kimura J (1997) Nicotine protects cultured cortical neurons against glutamate-induced cytotoxicity via alpha7-neuronal receptors and neuronal CNS receptors. Brain Res 765(1):135–140

Kihara T, Shimohama S, Sawada H, Honda K, Nakamizo T, Shibasaki H, Kume T, Akaike A (2001) Alpha 7 nicotinic receptor transduces signals to phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase to block A beta-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity. J Biol Chem 276(17):13541–13546

Kita Y, Ago Y, Takano E, Fukuda A, Takuma K, Narsuda T (2013) Galantamine increases hippocampal insulin-like growth factor 2 expression via a7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in mice. Psychopharmacologia 225(3):543–551

Kita Y, Ago Y, Higashino K, Asada K, Takano E, Takuma K, Matsuda T (2014) Galantamine promotes adult hippocampal neurogenesis via M1 muscarinic and α7 nicotinic receptors in mice. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 17(12):1957–1968

Kojima M, Kim JS, Uchimurea H, Hirano M, Nakahara T, Matsumoto T (1981) Effect of thyroidectomy on choline acetyltransferase in rat hypothalamic nuclei. Brain Res 209:227–230

Liu JH, Bijlenga P, Occhiodoro T, Fischer-Lougheed J, Bader CR, Bernheim L (1999) Mibefradil (Ro 40-5967) inhibits several Ca2+ and K+ currents in human fusion-competent myoblasts. Br J Pharmacol 126(1):245–250

Lorrio S, Sobrado M, Arias E, Roda JM, García AG, López MG (2007) Galantamine postischemia provides neuroprotection and memory recovery against transient global cerebral ischemia in gerbils. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 322(2):591–599

Ma K, Yang LM, Chen HZ, Lu Y (2013) Activation of muscarinic receptors inhibits glutamate-induced GSK-3β overactivation in PC12 cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin 34(7):886–892

McNulty MM, Hanck DA (2004) State-dependent mibefradil block of Na+ channels. Mol Pharmacol 66(6):1652–1661

Melancon BJ, Tarr JC, Panarese JD, Wood MR, Lindsley CW (2013) Allosteric modulation of the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor: improving cognition and a potential treatment for schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease. Drug Discov Today 18(23–24):1185–1199

Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ, Wainer BH, Levey AI (1983) Central cholinergic pathway in the rat: an overview based on an alternative nomenclature (Ch1-Ch6). Neuroscience 10:1185–1201

Moriguchi S, Zhao X, Marszalec W, Yeh JZ, Fukunaga K, Narahashi T (2009) Nefiracetam and galantamine modulation of excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission via stimulation of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat cortical neurons. Neuroscience 160(2):484–491

Moriguchi S, Shioda N, Yamamoto Y, Tagashira H, Fukunaga K (2012) The T-type voltage-gated calcium channel as a molecular target of the novel cognitive enhancer ST101: enhancement of long-term potentiation and CaMKII autophosphorylation in rat cortical slices. J Neurochem 121:44–53

Navarro E, Buendia I, Parada E, León R, Jansen-Duerr P, Pircher H, Egea J, Lopez MG (2015) Alpha7 nicotinic receptor activation protects against oxidative stress via heme-oxygenase I induction. Biochem Pharmacol 97(4):473–481

Niture SK, Jaiswal AK (2012) Nrf2 protein up-regulates antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 and prevents cellular apoptosis. J Biol Chem 287(13):9873–9886

Noreen H, Yabuki Y, Fukunaga K (2017) Novel spiroimidazopyridine derivative SAK3 improves methimazole-induced cognitive deficits in mice. Neurochem Int 108:91–99. In press

Oh JD, Butcher LL, Woolf NJ (1991) Thyroid hormone modulates the development of cholinergic terminal fields in the rat forebrain relation to nerve growth factor receptor. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 59:133–142

Pandya AA, Yakel JL (2013) Effects of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor allosteric modulators in animal behavior studies. Biochem Pharmacol 86(8):1054–1062

Parisa SD, Fahimeh J (2015) Sensitive amperometric determination of methimazole based on the electrocatalytic effect of rutin/multi-walled carbon nanotube film. Bioelectrochemistry 101:66–74

Perez-Reyes E (2003) Molecular physiology of low-voltage-activated t-type calcium channels. Physiol Rev 83(1):117–161

Qian J, Zhang JM, Lin LL, Dong WZ, Cheng YQ, Su DF, Liu AJ (2015) A combination of neostigmine and anisodamine protects against ischemic stroke by activating α7nAChR. Int J Stroke 10(5):737–744

Robinson L, Platt B, Riedel G (2011) Involvement of the cholinergic system in conditioning and perceptual memory. Behav Brain Res 221:443–465

Sadigh-Eteghad S, Talebi M, Mahnoudi J, Babri S, Shanehbandi D (2015) Selective activation of a7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor by PHA-543613 improves Aβ25-35-mediated cognitive deficits in mice. Neuroscience 298:81–93

Sawin S, Brodish P, Carter CS, Stanton ME, Lau C (1998) Development of cholinergic neurons in rat brain regions: dose-dependent effects of propylthiouracil-induced hypothyroidism. Neurotoxicol Teratol 20:627–635

Schwob JE, Szumowski KEM, Stasky AA (1992) Olfactory sensory neurons are trophically dependent on the olfactory bulb for their prolonged survival. J Neurosci 12:3896–3919

Shaw S, Bencherif M, Marrero MB (2002) Janus kinase 2, an early target of alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-mediated neuroprotection against Abeta-(1-42) amyloid. J Biol Chem 277(47):44920–44924

Shin SS, Dixon CE (2015) Targeting α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: a future potential for neuroprotection from traumatic brain injury. Neural Regen Res 10(10):1552–1554

Shioda N, Yamamoto Y, Han F, Moriguchi S, Yamaguchi Y, Hino M, Fukunaga K (2010) A novel cognitive enhancer, ZSET1446/ST101, promotes hippocampal neurogenesis and ameliorates depressive behavior in olfactory bulbectomized mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 333(1):43–50

Suzukawa K, Kondo K, Kanaya K, Sakamoto T, Watanabe K, Ushio M, Kaga K, Yamasoba T (2011) Age-related changes of the regeneration mode in the mouse peripheral olfactory system following olfactotoxic drug methimazole-induced damage. J Comp Neurol 519:2154–2174

Takada-Takatori Y, Kume T, Izumi Y, Ohgi Y, Niidome T, Fujii T, Sugimoto H, Akaike A (2009) Roles of nicotinic receptors in acetylcholinesterase inhibitor-induced neuroprotection and nicotinic receptor up-regulation. Biol Pharm Bull 32(3):318–324

Tan PP, Yuan HH, Zhu X, Cui YY, Li H, Feng XM, Qiu Y, Chen HZ, Zhou W (2014) Activation of muscarinic receptors protects against retinal neurons damage and optic nerve degeneration in vitro and in vivo models. CNS Neurosci Ther 20(3):227–236

Tong H, Chen GH, Liu RY, Zhou JN (2007) Age-related learning and memory impairments in adult-onset hypothyroidism in Kunming mice. Physiol Behav 91:290–298

Wu X, Liu H, Zhu X, Shen J, Shi Y, Liu Z, Gu M, Song Z (2013) Efficacy and safety of methimazole ointment for patients with hyperthyroidism. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 36:1109–1112

Yabuki Y, Jing X, Fukunaga K (2017a) The T-type calcium channel enhancer SAK3 inhibits neuronal death following transient brain ischemia via nicotinic acetylcholine receptor stimulation. Neurochem Int 108:272–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2017.04.015

Yabuki Y, Matsuo K, Izumi H, Haga H, Yoshida T, Wakamori M, Kakehi A, Sakimura K, Fukuda T, Fukunaga K (2017b) Pharmacological properties of SAK3, a novel T-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channel enhancer. Neuropharmacology 117:1–13

Yakel JL (2013) Cholinergic receptors: functional role of nicotinic ACh receptors in brain circuits and disease. Pflugers Arch 465(4):441–450

Yamamoto Y, Fuknaga K (2013) Donepezil rescues the medial septum cholinergic neurons via nicotinic ACh receptor stimulation in olfactory bulbectomized mice. Adv Alzheimer’s Dis 2(4):161–170

Yamamoto Y, Shioda N, Han F, Moriguchi S, Fukunaga K (2013) Novel cognitive enhancer ST101 enhances acetylcholine release in mouse dorsal hippocampus through T-type voltage-gated calcium channel stimulation. J Pharmacol Sci 121:212–226

Zdanowski R, Krzyżowska M, Ujazdowska D, Lewicka A, Lewicki S (2015) Role of α7 nicotinic receptor in the immune system and intracellular signaling pathways. Cent Eur J Immunol 40(3):373–379

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants-in-aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan (Kakenhi 25293124 and 26102704 to K.F., and 15H06036 to Y.Y.), a Project of Translational and Clinical Research Core Centers from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (to K.F.), and the Smoking Research Foundation (to K.F.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

This chapter is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Fukunaga, K., Yabuki, Y. (2018). SAK3-Induced Neuroprotection Is Mediated by Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. In: Akaike, A., Shimohama, S., Misu, Y. (eds) Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Signaling in Neuroprotection. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-8488-1_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-8488-1_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-10-8487-4

Online ISBN: 978-981-10-8488-1

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)