Abstract

In HABIT-CHANGE several barriers for the adaptation of conservation management have been identified. Much information and many methods do not fit with planning reality and the decision context at site level. Management authorities as well as land users and stakeholders often lack sufficient expertise and incentives to initiate adaptation activities. At present, learning by doing still plays a fundamental role in the adaptation of conservation management. It is as much a social learning process as it is a science-based procedure. Adaptation to climate change is a cross-sectoral issue. Therefore, stakeholder involvement and guidance of land use-related adaptation activities are of major importance. Available resources and the institutional setting of protected areas have a considerable influence on the capacity and willingness to adapt. Many administrations are not sufficiently equipped to respond to the impacts of climate change. There is an urgent need to build capacity in protected areas to monitor, assess, manage and report the effects of climate change and their interaction with other pressures. More collaboration between science and management will help to develop expertise and identify the most important knowledge gaps.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

Climate is changing and nature is responding at increasing speed. Many protected areas are already noticing the first consequences for biodiversity. The timing of seasonal events like the first flowering date for plants and the breeding dates of birds have advanced as spring is taking place earlier in the year. Species are changing their geographic distribution northwards or to higher altitudes. Consequentially, typical ecological interactions like hatching of offspring and availability of food sources are disrupted in time or in space. In addition, extreme events like floods and heavy rain but also heat waves and dry seasons are changing their pattern and intensity. This has severe impacts on individual species and habitats. Altered water regimes or other abiotic conditions are likely to change the character of habitats and ecosystems. Projected future climate trends will further accelerate changes in distribution and abundance of endangered species and ecosystems, and intensify overall biodiversity loss.

Even though mitigation of climate change is of utmost importance, conservation management must also be adapted to climate change. Otherwise climate change impacts will result in the degradation of habitats, the extinction of species and the loss of ecosystem services that are essential for human well-being.

Adaptation to climate change is defined as the adjustment in ecological, social or economic systems to prevent or reduce harm or benefit from potential opportunities (Smit and Pilifosova 2001). Adaptation of conservation management means adjustments in management practices, decision-making processes and organisational structures (Welch 2005). Although the adaptation process should be started now, it must be planned as a long term process. It will be successful only if as many institutions and stakeholders as possible are actively involved and are willing to support it.

Scientists have an important role to play in the development of adaptation strategies, but to facilitate effective implementation of adaptation actions local communities and decision-makers are essential. Expertise and data provided by research are a basis for a transparent and understandable decision-making process, but scientific results need to be translated and presented in a form that is accessible to professionals and decision-makers and local stakeholders (Welch 2005). The scientific information for local climate adaptation must be relevant for the decision at hand and tailored for the decision context. It should be authorised and trusted by the people affected, and transparent in the process of production. Meeting and addressing the needs, knowledge and language of local communities who have to implement adapted management practices is a major challenge for many scientists in climate impact research.

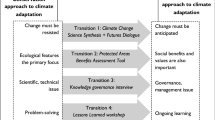

Acknowledging this challenge, the project HABIT-CHANGE initiated a science-management approach to plan jointly for adaptation in protected areas. This kind of collaborative research has already produced beneficial results in other areas (Littell et al. 2012; Lonsdale and Goldthorpe 2012). The science-practice partnership for collaborative research proved to be invaluable for testing useful methods, the identification of applicable solutions and the enhancement of practical conservation management within HABIT-CHANGE. It was built on an intensive dialogue between an interdisciplinary panel of scientists and local management and facilitates the co-production of knowledge. In this process several barriers to the practical implementation of theoretical concepts were identified. Much data and many methods provided by science did not fit with planning reality and the decision context of protected area management. On the other hand, many management practices were lacking a foundation in solid facts and evaluation of their success was often neglected. Furthermore, it seems that much of the available knowledge and guidance on adaptation of conservation management does not reach local management.

From the experience gained in the project we could see that climate change is rarely perceived and accepted as a high priority challenge on site level. There is often too little awareness that climate change is already a main driver of biodiversity loss and that its significance will increase even more in the future. Usually, neither management authorities nor land users and stakeholders have enough information, knowledge or incentives to plan and negotiate necessary adaptations to climate change. The adaptive capacity of local institutions like the administrations of National Parks or Biosphere Reserves is a crucial component too. The lack of expertise, methods and tools for climate adaptation as well as limited resources prevents proper management and adaptation (Fig. 20.1). The institutional setting of protected areas influences capacity and willingness to respond to new challenges and opportunities. This institutional adaptive capacity is at least as important for the conservation of biodiversity at the local level as the biological capacity of species to adapt at the level of individuals (e.g. by changes in phenology), populations (e.g. by migration) or species (e.g. by evolution).

From the work documented in this book and the project implementation further insights have been gained for more specific topics. What we consider to be the most important lessons learned are summarised in the following subchapters.

2 Lessons Learned from Modelling, Impact Assessment and Monitoring

Climate change is often associated with melting glaciers, melting pole caps and rising sea levels; however, most impacts are more subtle and hidden and thus not as easy to identify. Several methods can help to generate knowledge about potential climate change impacts as well as the effectiveness of adaptation measures. In HABIT-CHANGE modelling of exposure, impact assessment and monitoring methods have been applied.

Regional climate modelling (see Chap. 2) estimates changes for a possible future climate. The project results reinforce the expectation that Central and Eastern Europe is a sensitive region in terms of climate change (Auer et al. 2007). A distinct trend for temperature rise is projected while a shift of precipitation from summer to winter becomes visible. Due to considerable regional climate variability a high spatial resolution of future climate scenarios seems advisable to support local decision-making. This may increase uncertainty of the extent of expected future changes, but this information is also important as it provides a bandwidth of the potential changes.

Based on climate scenarios it is possible to calculate the impacts on further parameters of the natural balance, like water balance (see Chap. 3), flooding, soil-moisture, or species distribution. Modelling water balance is a key issue concerning future habitat development since most habitats are affected by changing hydrological conditions (see Chap. 4). Yet incomplete knowledge on ecological responses means that conservation management will inevitably experience surprising impacts in the future and needs to prepare for unexpected effects.

The issue of uncertainty also arises in the case of parameter-related modelling, since models are only simplifications of reality (see Chap. 5). Errors cannot be avoided since a model output strongly relies on the understanding and reproduction of real natural processes (Maslin and Austin 2012) and on the quality of its input data. Thus, modelling results should be used with care in the decision-making process (Millner 2012). On the other hand, models allow for an illustration of potential future developments, especially when using different scenarios, and thus support action and adaptation to impacts.

Impact assessment in HABIT-CHANGE followed the framework of IPCC (2001), consisting of the sensitivity and the exposure which defined the potential impacts (see Chap. 8). The aim was to apply a simple and transferable approach that is understandable for conservation managers. The framework requires only a minimum of local data and results in sensitivity maps and potential impact maps per season. The approach does not incorporate adaptive capacity; however, it can be a valuable assessment tool for climate-induced impacts on habitats. Identifying sensitivity of species and habitats is a good way of producing relevant information on the local level, especially when downscaled climate projections are not available. First of all, it supports the identification of habitats that are very susceptible to climatic changes. Furthermore, it helps to focus measures and activities as well as setting priorities. The sensitivity assessment allows for ‘what if’ scenarios. It can be used to exemplify the potential direction of habitat dynamics for different temperature changes (e.g. 2 °C).

Monitoring with all its facets is a crucial aspect of documenting and understanding the effects of changes in the landscape, biodiversity or specific parameters caused by human or natural impacts. A wide variety of appropriate methods for monitoring already exist, but they often lack the capacity for continuous long-term application.

In HABIT-CHANGE different monitoring methods have been applied. The objective was to provide indicators of potential climate change impacts (see Chap. 6) by the application of in-situ or Earth observation (see Chap. 7) methods. In-situ methods (like meteorological observations, soil moisture or water level sensor measurements, monitoring animal and plant populations) were applied to monitor specific aspects in the diverse investigation areas. Remote sensing approaches require a highly site and context specific design to fit data, methods and indicators and derive useful results. Short-term indicators can be used, e.g. to monitor the percentage of natural tree types at Natura 2000 sites, and long-term indicators can be utilised, for instance, to monitor the immigration of beech in a spruce dominated region. Also retrospective analysis can be an interesting source to analyse historical developments e.g. using remote sensing data from the last decades or historical maps from the last centuries. For continuous remote sensing monitoring comparable data sources with a high revisit rate and an appropriate spatial and spectral resolution are required.

In addition, coordination and standardisation for monitoring changes in biodiversity and impacts of climate change are necessary on a larger scale. Monitoring programmes should cover regional and national levels and provide for centralised data management, so that biodiversity status and its responses to climate change can be identified. Monitoring programmes for protected areas should focus on impacts and effectiveness of management activities within the areas. Only harmonised monitoring methods allow for an exchange of results between areas and provide a network of data to identify regional or continental trends. Furthermore, monitoring is an integrative part of the Adaptive Management cycle. Results can be used to review the performance of measures and for awareness raising activities.

In summary, it can be said that a lot of effort is needed to generate this kind of scientific-based knowledge. On the other hand much specific local expertise exists that should be captured (e.g. within a stakeholder involvement process) and used.

The most important finding was that science-based results need to be broken down to locally applicable knowledge for conservation management. There are several techniques available, like visualisations and maps, story-telling or experimental games that can illustrate the regional effects of climate change and its impacts on everyday activities.

3 Lessons Learned from the Process of Adapting Conservation Management

During recent years guidelines and concepts for the adaptation of conservation management have mushroomed (e.g. Baron et al. 2009; Cross et al. 2012; European Commission 2012; Glick et al. 2011a; Hansen and Hoffmann 2011; Lawler 2009; Welch 2005). Building on this wealth of literature and intensive discussions a framework for the adaptation of conservation management in protected areas of Central and Eastern Europe was drafted. The framework aimed at the development of Climate Change-Adapted Management Plans (CAMPs).

The application of this framework in six protected areas showed that the framework needed to be adapted to the site-specific conditions and management tasks. Sometimes additional steps were necessary and some required extra efforts. Particularly the definition of objectives and scope of the adaptation process needs special attention, and a clear definition of the area to be analysed, the problems and sectors to be included (e.g. agriculture, tourism) and target groups to be addressed is required. These decisions are essential to identify adequate methods for the assessment and to streamline stakeholder involvement.

In HABIT-CHANGE the development of a conceptual impact model that helps to identify drivers and pressures as well as their interaction was an integrated part of the assessment. However, there are also good reasons to include it as an individual step (e.g. Cross et al. 2012; Rannow 2011).

Based on the experience gained in the project, we consider the framework as a basic structure. Protected area managers may select and add elements from the plethora of frameworks that they consider useful for their specific situation. The willingness to adapt is more important than the strict application of any framework, guideline or handbook. At present, experimenting as well as learning by doing still plays a fundamental role in the adaptation of conservation management. Climate adaptation is as much a social learning process as it is a science-based procedure. It has to be considered a continuous process as knowledge about climate change, its impacts and the effectiveness of management will grow. In this context, Adaptive Management is a promising concept for gaining new knowledge and adjusting conservation efforts to changing conditions on the local level.

However, the time to initiate the adaptation process is now. Several areas have learned that climate impacts are already evident on the local level and management strategies and measures need to be adapted. Some management activities might even become superfluous with changing climate conditions. Especially when it comes to large restoration projects, the consideration of climate impacts is crucial for their long term success and changes might be necessary to ensure their effectiveness.

Early adaptation can help to reduce financial loss and preparedness can help to save money otherwise necessary for expensive emergency actions. In addition, there is a great wealth of local knowledge and a plethora of readily available research results, so that adaptation processes can be initiated without extensive investments or modelling efforts. Nevertheless, adaptation to climate change does not come free of charge. Adaptation of protected area management to climate change requires financial and methodological assistance. Many elements of the adaptation process cannot be implemented by protected area management alone. Support needs to be provided by scientific, regional or national partners. Management of protected areas faces the challenge of establishing new coalitions and strong cooperations in order to make adaptation work.

4 Lessons Learned from Stakeholder Involvement and Awareness Raising

The conservation status of many habitats is influenced by current land use practices like agriculture, forestry or tourism and their intensity. Most protected habitats can only be maintained through cooperation between protected area management and land users. Especially in the context of the cultural landscapes of Europe, only a few core zones in strictly protected areas like National Parks are solely dedicated to the conservation of natural habitats and exclusively managed by protected area administrations. In addition, it is already obvious that uncoordinated adaptation strategies by different land users will lead to new and severe conflicts, especially concerning water resources. Therefore in times of climate change the active involvement of stakeholders in the setup and implementation of management and conservation policies is essential for their success (Forshay et al. 2005; Harris et al. 2006; Maltby 1991; Walker et al. 2002). Sustainable land use requires an integrated approach involving conservation goals, economic growth, social welfare and climate change adaptation. Both nature and society will benefit from highly resilient biodiversity protection structures. Planned adaptation measures will affect land use practices, and their implementation will only be possible with the support of local stakeholders. However, adaptation to climate change is not only a challenge; it offers a chance to reshape the future of land use and conservation strategies for the benefit of all.

The main objectives of stakeholder involvement for climate-adapted conservation management are:

-

to identify the range of stakeholders and land users (and those who are assessed as being especially affected by climate change),

-

to enhance knowledge on climate change and land use-related problems,

-

to include local knowledge on climate-related changes and their impacts,

-

to identify and anticipate conflicts between planned and autonomous adaptation.

Effective stakeholder involvement should be based on a stakeholder analysis. This includes three steps:

-

Identification and classification of target groups including characteristics of target groups and their interrelationships,

-

Analyses of expectations of target groups and scope of involvement,

-

Development of a participation concept for stakeholder involvement.

The stakeholder involvement must be context specific, because target groups have different levels of knowledge, different social dynamics and different forms of communication. Consequently, there will be no general recipe for organising stakeholder dialogue that can be beneficially applied to all places or participants.

The target groups for the stakeholder involvement should be identified to enable specific communication concepts to be tailored. Following Reed et al. (2009) stakeholders can be classified into four groups based on their importance for and influence on the decision at hand. Key players are essential to make decisions and guarantee their implementation. Context setters (e.g. local authorities, ministries, business/trade unions) are stakeholders with much power but little interest in the problem. Subjects are those who are very interested in participating, but have little effect on the implementation (e.g. scientists, recreational users). Finally, the “Crowd” is defined as those stakeholders that have neither influence nor interest.

There are different forms of stakeholder involvement. This can range from passive forms of involvement like information or consultation, to active participation like collaboration, cooperation or delegation in the decision-making process (Muro et al. 2006). In the adaptation process, all stakeholders should be included in information and consultation activities. However, collaboration and cooperation might be restricted to key players and context setters.

The development of local adaptation strategies should be supported by scientific information and expertise. This structured communication of scientific results and processes can be termed science-based stakeholder dialogue (Welp et al. 2006). It is a social learning process based on communication and interaction in small groups. The science-based dialogue is not only targeted at stakeholders outside management. Sometimes communication of scientific background information on climate change and its impacts is also needed within administrations and between different conservation experts.

The science-based stakeholder dialogue should use several principles to ensure effective communication of climate knowledge on the local level. They can be summarised as follows (see CRED 2009; Futerra 2009; ICLEI 2009):

-

Build your message on local solutions and action instead of threats and warnings.

-

Reflect on the aims of your target audience and then show how your vision/project will make them happen.

-

Translate scientific data into concrete experience and make it visual and vivid.

-

Provide information focused on local problems and people’s everyday lives.

-

Present information in manageable chunks and use a reasonable timeframe (e.g. a strong and simple five-year plan).

-

Use spokespeople and allow stakeholders to take part in the conversation so that people have agency to act.

Stakeholder involvement should facilitate information exchange among participants and might help in finding win-win-solutions to climate change-related problems. It might also improve the public support of local adaptation actions and anticipate as well as manage related conflicts.

5 Summary of Support Needed and Actions to Be Taken

Conservation managers do not yet consider climate change adaptation in their day-to-day management. They will need further support to identify the relevant impacts of climate change, develop adaptation strategies and implement relevant measures. Scientific projects and programmes targeted at knowledge transfer can help to provide information and data. However, there is also a need to strengthen the adaptive capacity of protected areas. This capacity building should focus on:

-

The capacity to monitor, assess, manage and report the effects of climate change and their interaction with other pressures: Adequate investments for implementation have to be warranted, especially for long-term monitoring. Training for site managers and administration is essential to be prepared for changes resulting from climate change. Capacity building should also include technical and advisory services for financing and realising projects related to climate adaptation and biodiversity conservation.

-

Transnational cooperation and exchanges of experience with adaptation processes: Knowledge transfer across national borders and between managers of individual sites must be improved.

-

Awareness raising: Dedicated action should be taken to raise awareness of the local effects of climate change and the need for adaptation. The benefits of ecosystem-based adaptation through climate-adapted management in protected areas should be explored and illustrated in this regard. The potential of adaptation activities in protected areas to provide win-win situations for strengthening environmental, economic and societal resilience on the local level must be capitalised.

-

Guidance for land use-related adaptation activities: Cooperative processes based on stakeholder involvement should be strengthened to guide autonomous or unplanned adaptation of other sectors (e.g. farming, forestry or water management). Existing provisions for the protection of natural resources need to be enforced and economic instruments (e.g. subsidies and rural development programmes) must be harmonised to prevent maladaptation. Climate change policies of other sectors must not become an additional threat to biodiversity.

6 Priorities for Future Work and Open Questions

6.1 Adaptation as a Cross-Sectoral Issue

Biodiversity protection is an important component of sustainable economic growth and the protection of societal systems. Climate change adaptation cannot be planned and implemented separately for biodiversity protection. Climate change adaptation will involve changes in land and natural asset use. All sectors and policies have to plan adaptation strategies and often these sectors will need additional areas to mitigate the impacts of climate change, for adaptation measures and for nature disaster protection. As long as the adaptation of different sectors is not coordinated, conflicts will arise and the objectives of biodiversity and nature conservation will be harder to achieve, causing ecological and ultimately economic damage. Therefore, climate change adaptation needs to be understood as a coherent cross-sector task with common aims but specific measures.

6.2 Adaptation as a Long-Term Process

Adaptation processes are focused on the regional and local level. Climate change is starting to affect protected areas on the local level. This trend will continue and many regions will have to handle the intensifying impacts for a long time. Hence, adaptation is a long-term concern. Project-based activities like research or INTERREG projects are not able to provide long-term support. Projects like HABIT-CHANGE can only start processes and initiate actions that need local institutions as drivers of change. Adaptation planning is a first step in initiating a long-term adaptation process. It should help to improve understanding of the current and potential future impacts of climate change, raise awareness and acceptance for adaptation actions, start development of inclusive planning approaches that guarantee adequate stakeholder involvement and initiate Adaptive Management. However, without local-based and long-term-oriented support the implementation of climate adaptation will fail. Short-term oriented projects might even cause harm if they raise expectations in regard to results and participation in decision-making at the local level that cannot be fulfilled. This can result in participants becoming demotivated and valuable resources being used in an ineffective way.

6.3 Definition of Acceptable Change

In the long run, climate change will change distributions of species as well as the composition of habitats (Lindenmayer et al. 2008). It is unlikely that all specific conservation goals can be achieved with such grave environmental changes. In the future, we might be confronted with the need to balance near-term goals for the protection of species and habitats with more long-term goals for sustaining ecological systems and functions that are more likely to persist under changed climate conditions (Glick et al. 2011b). However, we might also find that not every change in species distribution or habitat composition is a reason for concern. In HABIT-CHANGE we have seen many changes that just accelerate natural succession. More research and open discussions will be necessary to answer the question as to which changes in habitats can be tolerated and which habitats should be preserved in their current state. It would be useful to define the limits for acceptable changes for each habitat type.

Nevertheless, some species and systems may only be conserved through intensive interventions (Heller and Zavaletta 2009). If no actions are capable of achieving the stated objective, it may even be necessary to adapt and revise objectives (Cross et al. 2012). Letting go of existing objectives and negotiating new aims will be a painful process for many conservationists. Furthermore, there is the risk that arguments involving climatic changes and reformulation of goals might be used to compromise years of protection efforts and achievements. Climate change must not be used as an excuse to limit conservation efforts or inefficient protection. To be prepared for this discussion a proactive conservation management should have answers ready on when, how much, and in what ways conservation management must be adapted (Glick et al. 2011b). Limits on acceptable change might help to identify thresholds related to when and where strategies could change from conserving the current state, to accommodating changes, to initiating transformation of habitats (Morecroft et al. 2012).

6.4 Further Need for (Transdisciplinary) Research

Climate change issues have become a high priority for research activities over the years. Nonetheless, many knowledge gaps still exist. Future research on the impacts of climate change on biodiversity should focus more on cooperation between science and practice. Our experience is that transdisciplinary projects provide a suitable setting for the identification of knowledge and data gaps, the formulation of relevant research questions, the understanding of climate-related problems, and the transfer of results into adaptation action. Many research activities are primarily focused on the production of information (e.g. about impacts and vulnerabilities) without much guidance on how this data should be used within the decision-making process. Consequently, there has not been a great deal of uptake into management and actions. Transdisciplinary research can help a shift towards a more action-oriented production of knowledge. In addition, the exchange of experience and good practice examples can be a strong motivation for action, whilst sharing unsuccessful experiences is important for understanding problems and identifying barriers to adaptation.

Scientific support can strengthen conservation, but more research into assessment tools and methods is necessary. It should be focused on:

-

The potential climate-induced reactions of specific habitats and species. Individual species will respond differently according to their tolerances to climatic changes, their ability to migrate to new locations, their potential to alter phenology (e.g. breeding date) or their dependence on shifting food sources.

-

A framework for the identification of adequate responses to climate-induced changes and succession of habitats. It should include evaluation criteria and thresholds for adequate reactions by conservation management.

-

Methods to handle results from multiple scenarios for future development and to harmonise climate projections for adaptation on the local level without prescribing data.

-

Useful and applicable indicators for evaluating possible local impacts of climate change on biodiversity at site level.

-

The potential effects of climate change on the competitiveness of alien invasive species.

References

Auer, I., Böhm, R., Jurkovic, A., Lipa, W., Orlik, A., Potzmann, R., Schöner, W., Ungersböck, M., Matulla, C., Briffa, K., Jones, P., Efthymiadis, D., Brunetti, M., Nanni, T., Maugeri, M., Mercalli, L., Mestre, O., Moisseline, J. M., Begert, M., Müller-Westermeier, G., Kveton, V., Bochnicek, O., Stastny, P., Lapin, M., Szalai, S., Szentimrey, T., Cegnar, T., Dolinar, M., Gajic-Capka, M., Zaninovic, K., Majstorovic, Z., & Nieplova, E. (2007). HISTALP – Historical instrumental climatological surface time series of the Greater Alpine Region. International Journal of Climatology, 27, 17–46.

Baron, J., Gunderson, L., Allen, C. D., Fleishman, E., McKenzie, D., Meyerson, L. A., Oropeza, J., & Stephenson, N. (2009). Options for National Parks and Reserves for adapting to climate change. Environmental Management, 44(6), 1033–1042. doi:10.1007/s00267-009-9296-6.

CRED – Center for Research on Environmental Decisions. (2009). The psychology of climate change communication: A guide for scientists, journalists, educators, political aides, and the interested public. New York: Center for Research on Environmental Decisions.

Cross, M. S., Zavaleta, E. S., Bachelet, D., Brooks, M. L., Enquist, C. A. F., Fleishman, E., Graumlich, L. J., Groves, C. R., Hannah, L., Hansen, L., Hayward, G., Koopman, M., Lawler, J. J., Malcom, J., Nordgren, J., Petersen, B., Rowland, E. L., Scott, D., Shafer, S. L., Shaw, M. R., & Tabor, G. M. (2012). The Adaptation for Conservation Targets (ACT) Framework: A tool for incorporating climate change into natural resource management. Environmental Management, 50, 341–351.

European Commission. (2012). Draft guidelines on climate change and natura 2000 – Dealing with the impact of climate change on the management of the Natura 2000 network. Luxembourg.

Forshay, K., Morzaria-Luna, H. N., Hale, B., & Predick, K. (2005). Landowner satisfaction with the Wetlands Reserve Program in Wisconsin. Environmental Management, 36, 248–257. doi:10.1007/s00267-004-0093-y.

Futerra. (2009). Sizzle – The new climate message. London

Glick, P., Stein, B. A., & Edelson, N. A. (Eds.). (2011a). Scanning the conservation horizon: A guide to climate change vulnerability assessment. Washington, DC: National Wildlife Federation.

Glick, P., Chmura, H. & Stein, B.A. (2011b). Moving the conservation goalpost: A review of climate change adaptation literature. Washington, DC: National Wildlife Federation. Retrieved from http://www.nwf.org/News-and-Magazines/Media-Center/Reports/Archive/2011/Moving-the-Conservation-Goalposts.aspx

Hansen, L., & Hoffmann, J. (2011). Climate Savvy – Adapting conservation and resource management to a changing world. Washington: Island Press.

Harris, J. A., Hobbs, R. J., Higgs, E., & Aronson, J. (2006). Ecological restoration and global climate change. Restoration Ecology, 14, 170–176. doi:10.1111/j.1526-100X.2006.00136.x.

Heller, N. E., & Zavaleta, S. (2009). Biodiversity management in the face of climate change: A review of 22 years of recommendations. Biological Conservation, 142, 14–32.

ICCP – Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Working Group II. (2001). Climate change 2001: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability: Contribution of Working Group II to the third assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge/ New York: Cambridge University Press.

ICLEI. (2009). Climate change outreach and communication guide. Boston.

Lawler, J. (2009). Climate change adaptation strategies for resource management and conservation planning. Annals of the New Yorker Academy of Science, 1162, 79–98.

Lindenmayer, D. B., Fischer, J., Felton, A., Crane, M., Michael, D., Macgregor, C., Montague-Drake, R., Manning, A., & Hobbs, R. J. (2008). Novel ecosystems resulting from landscape transformation create dilemmas for modern conservation practice. Conservation Letters, 1, 129–135.

Littell, J. S., Peterson, D. L., Millar, C. I., & O’Halloran, K. A. (2012). U.S. National Forest adapt to climate change through Science-Management partnership. Climatic Change, 110, 269–296.

Lonsdale, K. & Goldthorpe, M. (2012). Collaborative research for a changing climate: Learning from researchers and stakeholders in the ARCC programme. Adaptation and resilience in a changing climate coordination network. Oxford: UKCIP. Retrieved from www.arcc-cn.org.uk/wp-content/pdfs/ACN-collaborative-research.pdf

Maltby, E. (1991). Wetland management goals: Wise use and conservation. Landscape and Urban Planning, 20, 9–18.

Maslin, M., & Austin, P. (2012). Uncertainty: Climate models at their limit? Nature, 486, 183–184. doi:10.1038/486183a.

Millner, A. (2012). Climate prediction for adaptation: Who needs what? Climatic Change, 110, 143–167.

Morecroft, M. D., Crick, H. Q. P., Duffield, S. D., & Macgregor, N. A. (2012). Resilience to climate change: Translating principles into practice. Journal of Applied Ecology, 49, 547–555.

Muro, M., Hartje, V., Klaphake, A. & Scheumann, W. (2006). Pilot study in identifying and analysing stakeholders for the information and consultation according to Art. 14 of the EU Water Framework Directive in a River Basin. Umweltbundesamt Texte 27-06.

Rannow, S. (2011). Naturschutzmanagement in Zeiten des Klimawandels – Probleme und Lösungsansätze am Beispiel des Nationalparks Hardangervidda. Dissertation, Technische Universität Dortmund. Available at http://hdl.handle.net/2003/29142

Reed, M. S., Graves, A., Dandy, N., Posthumus, H., Hubacek, K., Morris, J., Prell, C., Quinn, C. H., & Stringer, L. C. (2009). Who’s in and why? A typology of stakeholder analysis methods for natural resource management. Journal of Environmental Management, 90, 1933–1949.

Smit, B. & Pilifosova, O. (2001). Adaptation to climate change in the context of sustainable development and equity. Contribution of the working group to the third assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (879–912). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Walker, B., Carpenter, S., Anderies, J., Abel, N., Cumming, G., Janssen, M., Lebel, L., Norberg, J., Peterson, G. D. & Pritchard, R. (2002). Resilience management in social-ecological systems: a working hypothesis for a participatory approach. Conservation Ecology 6(14). Retrieved from http://www.consecol.org/vol6/iss1/art14

Welch, D. (2005). What should protected areas managers do in the face of climate change? The George Wright Forum, 22(1), 75–93.

Welp, M., de la Vega-Leinert, A., Stoll-Kleemann, S., & Jaeger, C. C. (2006). Science-based stakeholder dialogues: Theories and tools. Global Environmental Change, 16, 170–181.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License, which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Copyright information

© 2014 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Rannow, S., Wilke, C., Gies, M., Neubert, M. (2014). Conclusions and Recommendations for Adapting Conservation Management in the Face of Climate Change. In: Rannow, S., Neubert, M. (eds) Managing Protected Areas in Central and Eastern Europe Under Climate Change. Advances in Global Change Research, vol 58. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7960-0_20

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7960-0_20

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-007-7959-4

Online ISBN: 978-94-007-7960-0

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)