Abstract

After March 2020, Corona virus containment measures significantly impaired the social relationships of many people. Against this background, this chapter examines how the perception of loneliness of people aged 46 to 90 changed during the first lockdown. The results are compared with those of 2014 and 2017.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Key messages

In the first wave of the pandemic, more people in the second half of life were lonely than in previous years. In 2020, the loneliness rate for people aged 46 to 90 was about 14 per cent, 1.5 times higher than in previous years. In 2014 and 2017, about 9 per cent of people in this age group felt lonely in both years.

The increase in the risk of loneliness in the first wave of the pandemic affected different population groups to the same extent. Loneliness increased to a similar extent for all age groups, for women and men, and for different educational groups.

Close social relationships did not protect people against increases in the risk of loneliness in the first wave of the pandemic. Close social relationships generally reduced the risk of loneliness: people in partnerships and people living in multi-person households were less likely to be lonely than people without partnerships and those living alone. However, the risk of loneliness increased at the same rate in both groups (people with and without close social relationships) between 2014/2017 and 2020.

Even having good contact with neighbours did not protect against increases in the risk of loneliness in the first wave of the pandemic. Good contact with neighbours was generally helpful: people in the second half of life who had good contact with their neighbours had a significantly lower risk of loneliness than people without good neighbourly contact. However, the risk of loneliness increased equally in both groups (people with and without good neighbourly contact) between 2014/2017 and 2020.

2 Introduction

To combat the Covid-19 pandemic, governments had to introduce pandemic-containment measures that significantly interfered with social relationships. For example, people had to wear masks and keep a distance of at least one and a half metres, preferably even more. They were asked to only maintain personal contact with a small group of people in order to avoid chain infections. Most contact with other people could therefore only take place via telephone and internet video conferencing services. Community activities—such as attending theatres, cinemas and museums, taking part in team sports and dance events and going to restaurants and pubs—were not possible. The measures reduced personal social contact predominantly to people who lived in the same household or neighbourhood and limited social support services, such as help with errands. In view of these social restrictions, the question of whether the Covid-19 pandemic was associated with an increase in loneliness, especially for people in older adulthood, has been repeatedly raised in the public debate.

The general risk of loneliness

This study of the experience of loneliness before and during the pandemic included people in the second half of life, aged between 46 and 90. The analysis compares loneliness rates in the summer of 2020 to loneliness rates at two points before the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, namely in 2014 and 2017. This comparison enables us to examine the influence of the pandemic on the risk of feeling lonely in the second half of life. Due to social distancing rules and the accompanying reductions in social interactions and social support, we should expect to find that there was an increase in loneliness in the first months of the Covid-19 pandemic (June/July 2020) compared to the period before the pandemic.

Risks of loneliness in different population groups

However, not all population groups may have been equally affected by the pandemic’s impact on loneliness risks. We therefore also investigated whether the increase in loneliness in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic differed for people of different ages, for women and men, and for people with different educational levels.

Age: The increase in loneliness might have varied depending on age, hitting some age groups harder than others. For example, the health effects of Covid-19 are often more serious in older people than in younger people (Robert Koch Institute 2020). Because older people may have been particularly cautious and isolated themselves more than younger people due to their greater risk of contracting severe Covid-19, older people may have been at greater risk of experiencing increases in loneliness due to the Covid-19 pandemic with increasing age (Luchetti et al. 2020). On the other hand, many older people may have had previous experiences of being and living alone and may hence have been better able to cope with the circumstances than people in middle adulthood (Böger and Huxhold 2018a), who are normally more involved in social networks and social activities (Huxhold et al. 2013). Therefore, the Covid-19 pandemic may have led to a greater increase in the risk of loneliness among people in their middle years than among older people (Entringer and Kröger 2020).

Gender: Under normal conditions, there are only minor differences between women and men regarding the risk of experiencing loneliness (Böger et al. 2017). However, women report more frequent contact with relatives and friends than men (Sander et al. 2017), and women usually have access to more social support (Fischer and Beresford 2015). Consequently, women may have experienced greater losses in their social relationships due to pandemic-containment measures than men and may thus have been at a greater risk of experiencing loneliness due to the pandemic. However, women’s better access to support may have also acted as a “buffer” that cushioned the impact of social distancing measures on the risk of loneliness.

Education: Educational status may also have had implications for experiences of loneliness. People with a high educational level have a greater number of social contacts, even in old age (Shaw et al. 2007, 2010), than people with a lower educational level. This may mean that more highly educated people felt more constrained by restrictions on social contact than people with lower levels of education. Yet, highly educated adults’ larger social networks may have served as a resource that helped to reduce the impact of the pandemic on the experience of loneliness.

Social integration as a buffer against pandemic-related loneliness risk?

Integration into spatially close social networks may have played a particularly important role in experiences of loneliness in the Covid-19 pandemic. These factors include partnerships, household composition and neighbourhoods. Generally, living in a partnership is a strong protective factor against loneliness (Böger and Huxhold 2018a). Living with other people in a multi-person household also protects against the risk of being lonely (Victor et al. 2000). Finally, the quality of neighbourly relationships also plays a role (Kemperman et al. 2019). We therefore investigated whether and to what extent partnerships, household composition and integration in the neighbourhood also ameliorated the risk of loneliness during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Questions

In this chapter, we present findings on three questions:

-

Did the risk of loneliness increase for people in the second half of life after the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic?

-

Did the risk of loneliness increase differently in different population groups after the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic? The analysis considers age, gender and educational level.

-

Did the risk of loneliness increase more for people who are not in a partnership, people living alone or people without close neighbourhood contacts as a result of the pandemic than it did for people in a partnership, people living in multi-person households and people with close neighbourhood contacts?

The results of this chapter are based on analyses of the 2014, 2017 and 2020 survey waves of the German Ageing Survey (DEAS; Vogel et al. 2020). The present analyses were based on the data from persons aged between 46 and 90. In this age range, information on loneliness was available for 7517 people in 2014, 5434 people in 2017 and 4609 people in 2020. Weighting was used to ensure that the results of the analyses of these data could be considered representative of the resident population in Germany between 46 and 90 years of age. Statistical testing was carried out using weighted logistic regressions.

Three survey years were considered (2014, 2017 and 2020). This enabled us to make statements on the specific influence of the pandemic. If the loneliness risk had been similar in all three years, we could have concluded that the pandemic had no influence on the loneliness risk. However, if the loneliness risk was similar only in 2014 and 2017 and increased significantly in 2020, we could have concluded that the pandemic had an influence on the loneliness risk.Footnote 1

2.1 Loneliness

Loneliness was measured with a loneliness scale (de Jong Gierveld et al. 2006). The scale contained three positive and three negative statements that respondents could agree or disagree with on a four-point scale from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree). The individual statements are:

-

I miss having people around among whom I feel comfortable (negative statement, indicates loneliness)

-

There are plenty of people I can rely on when I have problems (positive statement, does not indicate loneliness)

-

I often feel rejected (negative statement, indicates loneliness)

-

There are many people I can trust completely (positive statement, does not indicate loneliness)

-

I miss emotional security and warmth (negative statement, indicates loneliness)

-

There are enough people I feel close to (positive statement, does not indicate loneliness).

People were counted as “lonely” if they agreed or strongly agreed with the majority of the negative statements and disagreed or strongly disagreed with the majority of the positive statements.Footnote 2

2.2 Age, Gender and Education

Age: Four age groups were formed to examine the role of age: 46–55-year-olds (17.1 per cent of respondents), 56–65-year-olds (28.8 per cent of respondents), 66–75-year-olds (29.1 per cent of respondents), and 76–90-year-olds (25.0 per cent of respondents).

Gender: Women (50.0 per cent) and men (50.0 per cent) were identified based on self-reports.

Education was divided into three groups: People with a low educational level (6.3 per cent of respondents), medium educational level (50.2 per cent of respondents) and high educational level (43.5 per cent of respondents).

2.3 Social Resources in Close Proximity

Social resources in close proximity were assessed based on partnership status, household size and neighbourhood relations. This information was collected in 2014, 2017 and 2020.

Partnership status was determined with the question: “Do you have a spouse or steady partner?” The answer to this question was used to form two groups (partner: 77.7 per cent of respondents; no partner: 22.3 per cent of respondents).

Household: Household size was measured by asking people: “How many people in total live in your household, including yourself?” The analysis distinguished between two types: those who lived with others and those who lived alone (living with others: 78.4 per cent of respondents; living alone: 21.6 per cent of respondents).

Neighbourhood relations: The availability of close neighbourly relations was assessed by the following question: “How close is your contact with your neighbours currently?” The response categories were “no contact”, “only rare”, “not very close”, “close” and “very close”. The response categories were combined. The answer categories “close” and “very close” relations were combined into “close contact with neighbours” (43.0 per cent of respondents). All other response categories were combined into “no close contact” (57 per cent of respondents).

3 Findings

3.1 Increases in Loneliness Rates After the Start of the Pandemic

The analyses show that the risk of loneliness increased due to the Covid-19 pandemic (Fig. 10.1). Loneliness rates were around 9 per cent in both 2014 and 2017. In contrast, the loneliness rate in 2020 was 13.7 per cent, 4.8 percentage points higher than in 2014 and 2017. The difference between the 2014/2017 loneliness rates and the 2020 loneliness rate was statistically significant.

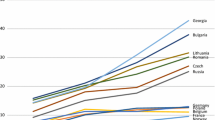

3.2 No Group Differences in the Increase in Loneliness Rates in the Pandemic

Age: Similar increases in loneliness risk were evident in all age groups in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic (Fig. 10.2). For those aged 46 to 55, loneliness rates were 10.2 per cent in 2014 and 10.7 per cent in 2017, but they were 16.4 per cent in 2020. The picture is similar for other age groups (56–65-year-olds: 9.9 per cent in 2014, 9.0 per cent in 2017 and 12.3 per cent in 2020; 66–75-year-olds: 6.3 per cent in 2014, 7.9 per cent in 2017 and 13.5 per cent in 2020; 76–90-year-olds: 8.1 per cent in 2014, 7.6 per cent in 2017 and 11.9 per cent in 2020).

Source DEAS 2014 (n = 7517), DEAS 2017 (n = 5434), DEAS 2020 (n = 4609), weighted analyses, rounded estimates. The difference between 2017 and 2020 is significant for all groups except the low educated. The increase between 2017 and 2020 is about the same for all groups. There are no significant differences in the increase between age groups, between genders or between educational levels

Loneliness rates by survey year, age, gender and educational level (in per cent).

The differences in loneliness rates were relatively small between all age groups in each survey wave. In 2014, the 66–75-year-old group had a significantly lower loneliness rate than the younger groups of 46–55-year-olds and 56–65-year-olds. In 2017, the loneliness rate was significantly lower among 76–90-year-olds than among 46–55-year-olds. All other differences between age groups were not significant.

Loneliness rates in 2020 (during the pandemic) were significantly higher than the average rates in 2014 and 2017 (before the pandemic) in all age groups. The difference in loneliness rates between 2014/2017 and 2020 was statistically at a comparable level in all groups. Thus, there was no evidence that the loneliness rate in any given age group increased more than the loneliness rate in any other age group.

Gender: The increase in loneliness rates between the pre-pandemic period (2014/2017) and during the pandemic (2020) was equal in size and statistically significant for both genders (Fig. 10.2). Among women, the loneliness rates were 8.4 per cent in 2014 and 9.6 per cent in 2017, compared to 13.5 per cent in 2020. Among men, the loneliness rates were 9.1 per cent in 2014 and 8.3 per cent in 2017 compared to 13.8 per cent in 2020. Women’s and men’s loneliness risks did not differ statistically significantly from each other at any time points (2014, 2017, 2020).

Source DEAS 2014 (n = 7517), DEAS 2017 (n = 5434), DEAS 2020 (n = 4609), weighted analyses, rounded estimates. The difference between 2017 and 2020 is significant for all groups. The increase between 2017 and 2020 is about the same for all groups. There are no significant differences in the increase between people living alone and those not living alone, between people in a partnership and those without a partnership, or between people with a close relationship with their neighbours and those without this relationship

Loneliness rates by survey year and social integration (in per cent).

Education: Comparing the pre-Covid-19 period (2014/2017) and the Covid-19 period (2020), we found increases in loneliness at all educational levels (Fig. 10.2). The corresponding figures are 12.0 per cent, 11.4 per cent and 12.6 per cent for people with a low educational level, 8.8 per cent, 9.2 per cent and 14.6 per cent for people with a medium educational level and 7.9 per cent, 8.2 per cent and 12.8 per cent for people with a high educational level (for 2014, 2017 and 2020 respectively). The increase between 2014/2017 and 2020 was only statistically significant for the medium and high education groups. However, the increases in the high and medium education groups were not more pronounced than the increase for the people with a low educational level.

The comparison between education groups showed that low educated individuals had a higher risk of loneliness in 2014 than people with medium and high educational levels. The medium and high education groups did not differ significantly from each other at that time. No statistically significant differences in education were found for 2017 and 2020.

3.3 Social Resources in Close Proximity Were not a Buffer Against Loneliness in the Pandemic

People who had a partner, who did not live alone and who maintained close contact with their neighbours were less at risk of feeling lonely than people who did not have a partner, who lived alone and who did not maintain close contact with their neighbours (Fig. 10.3).

The loneliness rates found in the most recent survey wave for people living with others were also the highest to date: these were 7.3 per cent in 2014, 8.6 per cent in 2017 and 12.1 per cent in 2020 (Fig. 10.3). For people living alone, the figures for the corresponding years were 14.0 per cent, 10.6 per cent and 20.0 per cent. Thus, household size may be protective factor against loneliness: on average, the risk of loneliness was about 1.7 times higher among people living alone than among people living with others. However, the increase in loneliness rates between 2014/2017 (before the pandemic) and 2020 (during the pandemic) was similar for both groups—for people living alone and people living with others in the same household.

The situation was similar with regard to partnership status. The loneliness rates for people who had a partner were 7.1 per cent (2014), 7.9 per cent (2017) and 11.7 per cent (2020). For people who did not have a partner, the figures for the corresponding years were 14.6 per cent, 12.6 per cent and 19.0 per cent. Hence, having a partner was also a protective factor against loneliness: on average, the loneliness risk for people who did not have a partner was about 1.9 times higher than the loneliness risk for people who had a partner. But again, the increase in loneliness rates between 2014/2017 (before the pandemic) and 2020 (in the pandemic) was similar for people with and without a partner.

The presence of close contacts in the neighbourhood was also associated with a lower risk of loneliness but not with a lower increase in loneliness in the Covid-19 pandemic. People who maintained close contact with their neighbours had loneliness rates of 4.1 per cent in 2014, 3.5 per cent in 2017 and 8.2 per cent in 2020. For people who did not maintain close contact with their neighbours, the figures for the corresponding years were 12.7 per cent, 13.5 per cent and 15.8 per cent. In all waves, people who had close contact with their neighbours had a loneliness risk that was only about one third of the risk of loneliness for people who did not have this contact.

Overall, the analysis shows that social resources in close proximity were not related to a lower increase in loneliness in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic. It is true that in 2020 (as in 2014 and 2017), people who lived with others were less lonely than people who lived alone, people who had a partner were less lonely than those who did not, and people with close contacts in their neighbourhood were less lonely than those without these contacts. However, the increase in loneliness rates between 2014/2017 and 2020 affected all these groups to about the same extent.

4 Conclusion

Comparing loneliness rates in 2014 and 2017 with loneliness rates in 2020 gives a clear indication that the Covid-19 pandemic in June and July 2020 negatively affected the social lives of people aged between 46 and 90. The loneliness rate for people in the second half of life increased by about 1.5 times between 2017 and 2020, from 9 to 13.7 per cent. Most importantly, the pandemic-related increase in loneliness was similar in size for people in middle adulthood and older adulthood, for women and men, and for people with low, medium or high educational levels. In other words, the pandemic affected loneliness rates in all population groups equally. It must be emphasised again here that the German Ageing Survey (DEAS) only interviews people in private households. It is possible that the experience of loneliness in the Covid-19 pandemic was different for people living in nursing homes, perhaps due to restrictive visiting rules.

Contrary to what many in the public might have expected, people of advanced age (76 to 90 years) living in private households did not experience more loneliness in the pandemic than people in middle adulthood (46 to 55 years). This finding might be linked to the subjective nature of the experience of loneliness. Loneliness is a subjective feeling that only arises when there is a perceived discrepancy between one’s own social expectations and actual circumstances (Tesch-Römer and Huxhold 2019). People in middle age may, on average, have had greater resources to cope with the negative social impact of the pandemic than people in older age, such as access to online communication or a larger social network (Antonucci et al. 2019; Huxhold et al. 2013, 2020). Yet, it is precisely because of these advantages that they have higher expectations of a fulfilled social life. There is evidence that older people cope better with being alone—for instance, when they do not have a partner—than people in middle age (Böger and Huxhold 2018a). In addition, people in middle age may have been more likely to be affected by specific pandemic-related burdens, such as scaled-back childcare services or job worries, than people in older adulthood. These additional burdens may have limited time and energy that could have been invested in social relationships, especially in middle age. In addition, analyses of the German Ageing Survey have shown that middle-aged individuals were just as concerned about the pandemic as older people (see chapter “How did individuals in the second half of life experience the Covid-19 crisis? Perceived threat of the Covid-19 crisis and subjective influence on a possible infection with Covid-19”). This could imply that older people did not in actuality restrict their social lives more than younger people. Considering these arguments, it is possible that loneliness rates rose equally across all age groups in the pandemic due to a confluence of factors.

The analyses also revealed that the increase in loneliness rates, presumably triggered by the pandemic, did not differ between men and women or between educational groups. These findings could also be explained by an interplay of several mutually compensating factors. Women were likely to suffer greater losses in their social activities as a result of the pandemic than men, and those with medium or higher levels of education were more likely to experience greater losses in their social contacts than people with a low educational level, since both women and highly educated adults were more socially active than men and people with a lower educational level before the pandemic (Fischer and Beresford 2015; Sander et al. 2017; Shaw et al. 2010). At the same time, both women and more highly educated people had greater social resources (Fischer and Beresford 2015; Shaw et al. 2007) than men and less well-educated ones. For example, women spend more time on average maintaining social networks and have access to more social support than men (Sander et al. 2017; Fischer and Beresford 2015). This may have helped those groups to mitigate the negative effects of social distancing measures.

The normally effective protective factors of social resources in close proximity—of living together with other people in a household, having a partner and having good neighbourhood relations—were not associated with a lower increase in the risk of loneliness at the beginning of the pandemic. It is possible that people who are well integrated in their local social environment had higher expectations for their social life overall and evaluated pandemic restrictions more negatively than people who did not have such relationships. Because of these higher expectations, the generally protective effect of having social resources in close proximity may not have been effective during the first months of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Overall, the increase in loneliness during the pandemic is a cause for concern, as loneliness can have serious consequences for mental and physical health (Böger and Huxhold 2018b; Hawkley and Cacioppo 2010). It should also be noted that the longer people feel lonely, the more difficult it is for them to free themselves from their state of loneliness. Long periods of loneliness reduce self-worth and make it more difficult to connect with others (Hawkley and Cacioppo 2010). Therefore, increased rates of loneliness may have negative consequences that persist after the pandemic.

The Covid-19 pandemic has still not ended. For these reasons, the coronavirus crisis has made programmes that combat loneliness even more important (Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth 2021). In a certain sense, the pandemic even offers an opportunity. For as bad as the effects of the crisis have been on many people’s social embedding, they have also raised public awareness of the issue of loneliness. Since many more people experienced severe loneliness in the course of the pandemic, the stigmatisation of lonely people may even have decreased. For these reasons, we can hope that low-threshold measures to combat loneliness will be better accepted and disseminated in the aftermath of the pandemic. Thus, paradoxically, the pandemic could create better conditions for contacting the hard-to-reach group of lonely people.

Notes

- 1.

Technical information: the analyses tested whether the loneliness rates in 2014 and 2017 were statistically significantly different from each other. If this was not the case, the mean value of the loneliness rates 2014 and 2017 was compared with the loneliness rate 2020.

- 2.

Technical information: the values for statements 2, 4 and 6 were recoded—i.e. they were converted so that the value 4 indicates high loneliness and the value 1 indicates low loneliness. An average value was calculated from the values for all six statements, which can range from 1 (loneliness low) to 4 (loneliness high). People were counted as “lonely” if their scale value was greater than 2.5.

References

Antonucci, T. C., Ajrouch, K. J., & Webster, N. J. (2019). Convoys of social relations: Cohort similarities and differences over 25 years. Psychology and Aging, 34(8), 1158–1169. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000375

Böger, A., & Huxhold, O. (2018a). The changing relationship between partnership status and loneliness: Effects related to aging and historical time. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 75(7), 1423–1432. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby153

Böger, A., & Huxhold, O. (2018b). Do the antecedents and consequences of loneliness change from middle adulthood into old age? Developmental Psychology, 54(1), 181–197. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000453

Böger, A., Wetzel, M., & Huxhold, O. (2017). Allein unter vielen oder zusammen ausgeschlossen: Einsamkeit und wahrgenommene soziale Exklusion in der zweiten Lebenshälfte. In: K. Mahne, J. K. Wolff, J. Simonson & C. Tesch-Römer (Eds.), Altern im Wandel: Zwei Jahrzehnte Deutscher Alterssurvey (DEAS) (pp. 273–285). Wiesbaden: Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-12502-8_18

Entringer, T., & Kröger, H. (2020). Einsam, aber resilient—Die Menschen haben den Lockdown besser verkraftet als vermutet [DIW aktuell 46]. Berlin: Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung. https://www.diw.de/documents/publikationen/73/diw_01.c.791373.de/diw_aktuell_46.pdf (Zuletzt aufgerufen am 05.02.2021)

Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth [Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend] (2021). Einsamkeit im Alter. https://www.bmfsfj.de/bmfsfj/themen/aeltere-menschen/aktiv-im-alter/einsamkeit-im-alter/einsamkeit-im-alter/135712. (Last retrieved 05.02.2021)

Fischer, C. S., & Beresford, L. (2015). Changes in Support Networks in Late Middle Age: The Extension of Gender and Educational Differences. Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70(1), 123–131. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbu057

Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness Matters: A Theoretical and Empirical Review of Consequences and Mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 40(2), 218–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8

Huxhold, O., Fiori, K. L., & Windsor, T. D. (2013). The dynamic interplay of social network characteristics, subjective well-being and health: The costs and benefits of socio-emotional selectivity. Psychology and Aging, 28(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030170

Huxhold, O., Hees, E., & Webster, N. J. (2020). Towards bridging the grey digital divide: changes in internet access and its predictors from 2002 to 2014 in Germany. European Journal of Ageing, 17, 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-020-00552-z

Jong Gierveld, J. de, van Tilburg, T., & Dykstra, P. A. (2006). Loneliness and social isolation. In A. Vangelisti & D. Perlman (Eds.), Handbook of personal relationships (pp. 485–500). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511606632.027

Kemperman, A., van den Berg, P., Weijs-Perrée, M., & Uijtdewillegen, K. (2019). Loneliness of older adults: Social network and the living environment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(3), 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030406

Luchetti, M., Lee, J. H., Aschwanden, D., Sesker, A., Strickhouser, J. E., Terracciano, A., & Sutin, A. R. (2020). The trajectory of loneliness in response to COVID-19. American Psychologist. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000690.supp

Robert Koch Institute [Robert-Koch-Institut] (2020). SARS-CoV-2 Steckbrief zur Coronavirus-Krankheit-2019 (COVID-19). https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Steckbrief.html (Last retrieved 3.11.2020)

Sander, J., Schupp, J., & Richter, D. (2017). Getting Together: Social Contact Frequency Across the Life Span. Developmental Psychology, 53(8), 1571–1588. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000349

Shaw, B. A., Krause, N., Liang, J., & Bennett, J. (2007). Tracking changes in social relations throughout late life. Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62(2), S90–S99. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/62.2.S90

Shaw, B. A., Liang, J., Krause, N., Gallant, M., & McGeever, K. (2010). Age Differences and Social Stratification in the Long-Term Trajectories of Leisure-Time Physical Activity. Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 65(6), 756–766. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbq073

Tesch-Römer, C., & Huxhold, O. (2019). Social isolation and loneliness in old age.Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.393

Victor, C., Scambler, S., Bond, J., & Bowling, A. (2000). Being alone in later life: loneliness, social isolation and living alone. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 10(4), 407–417. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0959259800104101

Vogel, C., Klaus, D., Wettstein, M., Simonson, J., & Tesch-Römer, C. (2020). German Ageing Survey (DEAS). In: D. Gu & M. E. Dupre (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Gerontology and Population Aging. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69892-2_1115-1

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this license to share adapted material derived from this chapter or parts of it.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Huxhold, O., Tesch-Römer, C. (2023). Loneliness Increased Significantly among People in Middle and Older Adulthood during the Covid-19 Pandemic. In: Simonson, J., Wünsche, J., Tesch-Römer, C. (eds) Ageing in Times of the COVID-19 Pandemic . Springer VS, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-40487-1_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-40487-1_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer VS, Wiesbaden

Print ISBN: 978-3-658-40486-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-658-40487-1

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)