Abstract

The links between loneliness and overall morbidity and mortality are well known, and this has profound implications for quality of life and health and welfare budgets. Most studies have been cross-sectional allowing for conclusions on correlates of loneliness, but more recently, some longitudinal studies have revealed also micro-level predictors of loneliness. Since the majority of studies focused on one country, conclusions on macro-level drivers of loneliness are scarce. This chapter examines the impact of micro- and macro-level drivers of loneliness and loneliness change in 11 European countries. The chapter draws on longitudinal data from 2013 and 2015 from the Survey of Health, Aging, and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), combined with macro-level data from additional sources. The multivariable analysis revealed the persistence of loneliness over time, which is a challenge for service providers and policy makers. Based on this cross-national and longitudinal study we observed that micro-level drivers known from previous research (such as gender, health and partnership status, frequency of contact with children), and changes therein had more impact on loneliness and change therein than macro-level drivers such as risk of poverty, risk of social deprivation, level of safety in the neighbourhood.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

1.1 Background and Aim of the Chapter

The main focus of this chapter is on exclusion from social relations, and loneliness as an important outcome of this exclusion. Although exclusion from social relations is sometimes equated with loneliness, this is not the same. People can feel lonely in a crowd, while at the same time people who are socially excluded are not necessarily lonely (Weiss 1973). Nevertheless, [and as outlined in Burholt and Aartsen this section], loneliness is recognised as a critical outcome of exclusionary processes within the social relations domain. The consequences of loneliness are severe, including poor physical and mental health (Wilson et al. 2007; Holt-Lunstad et al. 2015) and increased health care and societal costs (Cacioppo and Cacioppo 2018). Loneliness occurs at all ages, with a higher prevalence in older-age ranging from 10% in northern European countries to 30% in southern and Eastern European countries (Yang and Victor 2011).

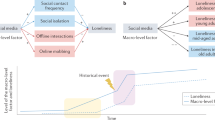

Cross-sectional studies on loneliness in older-age have produced robust evidence for a number of individual correlates of loneliness (further presented below), and a growing number of longitudinal studies have also provided evidence that some of these correlates are in fact micro-level drivers of loneliness, that is, leading to increased feelings of loneliness. Cross-national studies so far provided insight on macro-level correlates with loneliness, but none of these studies had a longitudinal design. Hence, our understanding of micro and macro-level drivers of loneliness is still limited (Courtin and Knapp 2017). The aim of this study is to advance our understanding of micro- and macro-level drivers of loneliness in later life, by examining a number of the well-established micro-level factors, along with several theoretically plausible macro-level drivers. We base the selection of macro-level drivers on the theoretical conceptualisation of social exclusion by Walsh et al. (2017). This framework of old-age exclusion identifies six key domains: neighbourhood and community; services, amenities and mobility; material and financial resources; social relations; socio-cultural aspects of society; and civic participation. The conceptual framework on social exclusion illustrates how exclusion from one domain is associated with exclusion in other domains.

1.2 Micro-Level Drivers of Loneliness

Micro-level drivers of loneliness can be grouped into three broad domains: demographic, social relationships and health-related factors. A meta-analysis of 182 studies examining correlates of loneliness found that gender accounted for 0.6% of variance, with females reporting more loneliness than men. This association was stronger among those aged 80 years and over (Pinquart and Sörensen 2003). Longitudinal studies confirm the increased risk of loneliness in women, but the gender difference becomes usually non-significant when other variables are taken into account (e.g. Nicolaisen and Thorsen 2014; Dahlberg et al. 2015). A weak association between higher age and loneliness can be observed (Pinquart and Sörensen 2003), but this association becomes insignificant in multivariable analyses (e.g. Dahlberg et al. 2015; Pikhartova et al. 2016). Other longitudinal studies did not find age effects (e.g. Aartsen and Jylhä 2011; Nicolaisen and Thorsen 2014). A larger and supportive network, and having a partner is associated with lower levels of loneliness (Pikhartova et al. 2016; Böger and Huxhold 2018), and recent partner loss increases the risk of loneliness (e.g. Dahlberg et al. 2015; Pikhartova et al. 2016). Only a few studies explicitly examined an association between contacts with adult children and loneliness. These studies found no significant association between having children and loneliness (Cohen-Mansfield et al. 2016; Dolberg et al. 2016). Self-reported health, poor functional status, and mobility difficulties are associated with loneliness (e.g. Cohen-Mansfield et al. 2016; Hawkley and Kocherginsky 2018). To our knowledge, no previous longitudinal studies on risk factors for loneliness in older adults has considered the potential effects of visual impairments. However, longitudinal studies about hearing impairments and loneliness found that an association between self-reported hearing status and speech-in-noise test scores were predictive of adverse effects on social and emotional loneliness in specific subgroups (i.e. emotional loneliness and men; social loneliness and people living with a partner) (Pronk et al. 2011, 2014).

1.3 Macro-Level Correlates of Loneliness

Cross-national studies so far revealed variations in the prevalence of loneliness across countries (Gierveld and Tilburg 2010; Yang and Victor 2011; Fokkema et al. 2012; Swader 2018; Hansen and Slagsvold 2019), across welfare state regimes (Nyqvist et al. 2019), and across other typologies of countries (Swader 2018), suggesting the existence of macro-level drivers of loneliness. Indeed, research from nine countries of the former Soviet Union (Stickley et al. 2013) revealed that loneliness was associated with hazardous health behaviours in some countries (Armenia, Kyrgyzstan and Russia), which may indicate cultural habits concerning alcohol use. Another study found a modifying effect of the cultural context on associations between loneliness and different types of social relations, and the authors concluded that familial relationships seem to be more important for prevalence of loneliness, than friends in collectivistic societies, while confidants (i.e. people with whom to discuss personal and intimate matters) are more important in individualistic societies (Lykes and Kemmelmeier 2014). While the modifying effect of the cultural context in associations between micro-level factors and loneliness is also found in other cross-national studies in Europe (Swader 2018; Nyqvist et al. 2019), it does not seem to hold for severe forms of loneliness (Swader 2018). Higher levels of severe loneliness in eastern European countries, as compared to northern European countries, were associated with inequalities in socio-economic resources (Hansen and Slagsvold 2015). The cross-sectional nature of these studies limits conclusions on the direction of effects, and hence our understanding of macro-level drivers.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design and Participants

Micro-level data come from SHARE (Börsch-Supan et al. 2013). SHARE is a multidisciplinary and cross-national panel database of microdata on health, socio-economic status, and social and family networks of more than 120,000 individuals aged 50 or older living in Europe. The first measurement took place in 2004. Every second year after that, a follow-up measurement took place, with the largest numbers of countries participating in the most recent waves of data collection. For the present study, we used data from wave five (W5, conducted in 2013) and wave six (W6, conducted in 2015) and included countries that participated in both waves. The countries comprised: Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Italy, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden. We excluded Israel, Switzerland and Luxemburg because of missing information on the macro-level variables. The total study sample was N = 52,562 at W5 of which N = 39,628 also participated in W6. SHARE W5 and W6 were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Council of the Max Planck Society. All participants provided written informed consent.

Macro-level data were derived from various databases: the World Bank for the GINI-index, the Eurobarometer for the level of ageism, the European Social Survey (ESS) for the proportion of people aged 55+ attending church once a month or more, and the percentage of people aged 55+ scoring five or higher on a religiousness scale from zero to ten. All other macro-level indicators were derived from tables of the Active Ageing Index (AAI) (UNECE, 2019). The AAI includes 22 indicators grouped into four domains (employment; participation in society; independent, healthy and secure living; capacity and enabling environment for active ageing). Data are available for all EU member states and some other European countries (Zaidi et al. 2013). Macro data for the years closest to the SHARE years included in this study come from 2012 and 2014.

2.2 Dependent Variable

Loneliness was measured with the short version of the Revised-University of California, Los Angeles (R-UCLA) scale (Russell et al. 1980; Hughes et al. 2004). The scale was based on three questions: How much of the time do you… (1) feel a lack of companionship, (2) feel left out, and (3) feel isolated from others [also see Myck et al. this volume for a discussion of the change in this loneliness measure over time and its relationship to material deprivation]. Answering categories are (1) often, (2) some of the time and (3) hardly ever or never. The R-UCLA score is the sum of the scores on these three variables and ranges from 3 to 9. The scores on the three questions were recoded so that a higher score reflects higher levels of loneliness.

2.3 Independent Variables at the Micro Level

Age reflects the year of birth of the respondent, and gender is dichotomised into 1 (men) and 2 (women). Three dummy variables were created to reflect partner status: never married; divorced; and widowed. Having a partner (inside or outside the household) was used as the reference category. Frequency of contact with children reflects the average number of contacts with children. Response categories range from daily (1) to never (7). The number of grandchildren reflects the number of grandchildren the respondent and his/her partner (if there is any) have altogether. Limited hearing [using hearing aids as usual] was assessed by asking “Is your hearing excellent” (1); very good (2), good (3), fair (4), and poor (5). Limited eyesight was based on the question “How good is your eyesight [using glasses or contact lenses as usual] for seeing things up close, like reading ordinary newspaper print”, with answers ranging from excellent (1) to poor (5). The extent to which people are health limitations (limited in activities because of health) was measured via a categorical variable with answering categories severely limited (1) limited, but not severely (2) and not limited (3). Changes in the contacts with children and number of (grand)children reflect the raw difference between W5 and W6 and recoded into decline (−1) no change (0) and improvement (+1). Change in hearing and change in eyesight reflect the raw difference between W5 and W6, and coded as decline (−1) if there were two or more scale points decline, no change (0) if the change was 1 or 0 scale points, and improvement (+1) if there was a gain of two-scale points or more. Change in health limitations reflects the raw difference between W5 and W6 and coded as decline (−1) if there were one or more scale points decline, no change (0) if the change was 0 scale points, and improvement (+1) if there was a gain of one scale point or more. Widowhood reflects situations where people were widowed at W6, but not at W5. Divorced reflects situations where people were divorced at W6, but not at W5.

2.4 Independent Variables at the Macro Level

Macro-level variables were derived from the various datasets described previously and are listed in Table 8.1. These variables concern the population aged 55 and above (if not indicated otherwise).

A difference between 2012 and 2014 in country-level indicators was calculated by subtracting the 2012 indicator from the 2014 indicator.

2.5 Analytical Approach

All analyses were conducted with SPSS version 26. The mean and the standard deviation for loneliness were calculated for each country separately. The rank order reflects the ranking of countries based on the loneliness score, with a lower number indicating a lower mean level of loneliness. Since the individual data is nested within the countries, we considered a multilevel regression model to estimate the associations between the micro- and macro-level variables. To test the relevance of the nested structure of the data, we first calculated the Variance Partition Coefficient (VPC), which was computed from a mixed effect linear model. The test shows that only 3.8% of the variance in loneliness can be attributed to differences between countries. We therefore decided to ignore the nested structure and conducted multivariable linear regression analyses instead with stepwise entering of blocks of independent variables. In the first block (M1), we entered the three dummy variables concerning the partner status. In the second block (M2), we additionally entered contact frequency with children and number of grandchildren; in the third block (M3) hearing, eyesight and health limitations were added. All macro-level variables were added in the last block (M4). Age and gender were included in all models. The extent to which micro- and macro-level factors, and changes therein, were associated with changes in loneliness was examined using the same approach as indicated above, but with loneliness at W5 included in the first step (M1). All changes in micro- and macro-level variables were added in M5 and M6 subsequently. Missing observations on any of the independent or dependent variables resulted in an exclusion of the case (list-wise deletion).

3 Results

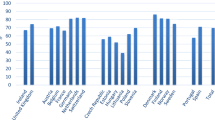

The baseline (W5) and follow-up (W6) levels of loneliness, and its standard deviation per country are presented in Table 8.2, and the baseline characteristics of the independent variables at baseline are shown in Table 8.3. Loneliness differs for the 11 countries included at both waves, with the lowest levels of loneliness in Denmark, Austria and Sweden, and the highest levels in Estonia, Italy and Czech Republic at W5. The rank order of countries according to average level of loneliness is the same at W6.

At baseline (W5), the average age is 66.2 years (range 55–95 years), 55.6% are female, 66.7% have a partner inside or outside the household, 5.4% are never married, 8.4% are divorced, and 14% are widowed. The average level of contacts with children is 2.7 indicating a frequency of contact between weekly and monthly. People on average have 2.8 grandchildren, score between good and very good for hearing and eyesight, and are on average somewhat, but not severely, limited in their activities because of health. Note that the country-specific scores indicate large variations in these characteristics.

Table 8.4 presents the results of the multivariable linear regression of loneliness at W6 on individual characteristics and country characteristics at W5. All models had significant F-values, indicating that the regression models predicted loneliness significantly well. Higher age and female gender are related to higher levels of loneliness, and this effect cannot be explained by other micro- or macro-level characteristics. Compared to those who have a partner at W5, those who are divorced or widowed at W5 have higher levels of loneliness at W6. Being never married is also related to increased levels of loneliness. This association is partly explained by the absence of contacts with children, as adding contact frequency with children results in a smaller regression coefficient for never married. A higher contact frequency with children is associated with higher levels of loneliness 2 years later, while having grandchildren is not significantly related to loneliness 2 years later. Problems with hearing and eyesight and health limitations are related to higher levels of loneliness 2 years later.

Macro characteristics that led to reduced levels of loneliness 2 years later were a lower proportion of people with poverty risk, a lower proportion of people with material deprivation [see Myck et al. this volume for a more detailed analysis of this relationship], a higher proportion of people feeling physically safe in their neighbourhood, and a higher percentage of religious people. Surprisingly, a higher level of access to health care services and a higher level of social contacts in W6 were associated with increased loneliness scores. The lowest row in Table 8.4 presents the explained variances for each model. It shows that the individual factors explain approximately 10% of the variation in loneliness, whereas the selected country characteristics additionally explain 2.6%

Finally, we conducted a multivariable linear regression, in which change in loneliness from W5 to W6 was regressed on the micro and macro characteristics at W5, and change in all variables between baseline and follow-up. As presented in Table 8.5, loneliness at W5 is a strong predictor of loneliness 2 years later, indicating that loneliness is relatively stable (r = 0.47). Age is related to changes in loneliness, but this effect becomes insignificant after controlling for changes in the individual characteristics (M6). Women have a stronger increase in loneliness than men, and this effect remains significant after including other individual and country characteristics. People who are married at both waves have the lowest increase in loneliness. Becoming widowed or divorced between W5 and W6 leads to a substantial increase in loneliness. A higher contact frequency and an increase in contact frequency with children is related to an increase in loneliness. The effect of the number of grandchildren on loneliness is borderline significant and loses its significance in the final model. However, an increase in the number of grandchildren was related to increases in loneliness. Limited hearing, eyesight limitations, and health limitations are related to a stronger increase in loneliness. None of the changes in the macro-level variables explained variance in loneliness, and hence M5 was the final model. The much higher proportion of explained variance of changes in loneliness compared to the first model is mainly due to the inclusion of loneliness at W5. Almost 30% of the variation in loneliness at W6 is explained by the level of loneliness at W5.

4 Discussion

Unsurprisingly, loneliness at wave 5 explained most of the change in loneliness at wave 6, which underlines the persistence of loneliness over time and the challenge for service providers and policymakers. Today, loneliness is accepted as a substantial driver of ill-health (Holt-Lunstad et al. 2015; Steptoe et al. 2012) and clearly contributes to the perception and experience of social exclusion. Likewise ill-health can be a driver of loneliness (Cohen-Mansfield et al. 2016; Hawkley and Kocherginsky 2018). The micro-level variables that demonstrated significant effects on the level of and change in loneliness were largely in line with the literature noted at the beginning of this chapter (e.g. Pinquart and Sörensen 2003). Loneliness increased significantly for women, and when there was a decline in hearing ability or eyesight and an increase in health limitations. However, a greater frequency of contact with children was also related to an increase in loneliness. Although counterintuitive at first sight, a higher contact frequency may be indicative of a worsening of the older adults’ personal situation that is associated with loneliness. If everything is fine, there is probably no need for an increased contact between the children and their parents.

Any significant effect of age disappeared when controlling for changes in the individual characteristics, which is basically what ageing is: a change in individual characteristics. While the number of grandchildren did not affect level of loneliness 2 years later, an increase in the number of grandchildren between W5 and W6 did, suggesting that a new grandchild leads to an immediate increase in loneliness but this effect fades after 2 years. This may relate to greater expectations of social interaction with children and grandchildren and disappointment when their children are more involved with their own children lessening contact with their parents. Having a partner leads to lower levels of loneliness and protects against becoming lonelier over time.

Macro-level factors leading to lower levels of loneliness were living in countries with low risks of poverty, low risks of material deprivation, safer neighbourhoods and higher levels of religiosity. Better access to health care services and a higher average level of social contacts were associated with increased levels of loneliness. While this is counter-intuitive, these results are probably country contextual. Loneliness is a subjective state. Living in a country where people generally have a high level of social contacts, may increase their own expectations, and normative orientations (Dykstra 2009), which makes it more likely to become lonely (Fokkema et al. 2012). In a similar vein, better access to health care services may raise people’s awareness of health issues of which they would not be aware if they had not contacted health care professionals. Two other macro-level variables did not produce significant differences in loneliness, ageism and median income. The result for ageism is surprising, and in contrast with earlier findings by Sutin et al. (2015). While we do not know a reason for this, one technical explanation might be that the variable was derived from a different database, the Eurobarometer. A lack of effect of the country’s median income may be too blunt a measure to identify the impact of income levels on loneliness, unlike the Active Ageing Index variables relating to poverty and material deprivation risk.

This study has focused on cross-national, longitudinal data on micro- and macro-level drivers in level and change of loneliness of older people with reference to specific domains of social exclusion. In the first series of regression models, estimating the effect of baseline micro- and macro-level drivers on level of loneliness 2 years later, indicated that 10% of the variation in loneliness was attributable to micro-level drivers, whereas macro-level drivers explained an additional 2.6%. This indicates that the country-level characteristics in this study have had only a modest influence on an individual’s feelings of loneliness. From the second series of regression models it was concluded that change in loneliness can be explained in terms of micro- and macro-level drivers at baseline. However, change in macro-level drivers did not additionally explain variation in loneliness change. Given the significant correlations with loneliness for most country-level variables in the various models reported in the results, it suggests estimated variance effects in loneliness are small over a two-year period and a greater longitudinal period may produce more significant results. It may also imply that country-level data may present too blunt a measure when searching for effects on an individual factor like subjective loneliness.

The two-year period of this study is a limiting factor when considering the results. A longer period with more waves could be expected to produce more robust outcomes, especially with the country-level variables that were applied. They do, however, confirm that individual factors contribute to changes in loneliness. Social exclusion variables at country-level point to influences on loneliness, but the variables like neighbourhood safety and poverty risk may be better collected at the individual level to gain a more precise measure of their impact [see Van Regenmortel this section].

5 Conclusion

The purpose of this chapter was to explore loneliness as an outcome of exclusion from social relations. Micro- and macro-level factors were analysed over two waves, 2 years apart, providing a dynamic measure of change. Most of the individual variables from the demographic, social relationships and health domains that we considered would predict loneliness did in fact do so. The micro-level factors contributed to the estimated variance in loneliness, while the macro-level variables demonstrated a more modest influence. This might reflect a methodological problem of extracting country-level results that are precise enough to be correlated with individual loneliness scores and the short two-year time period. The results provide insights into loneliness and loneliness change, and is one of few longitudinal studies to consider both micro and macro drivers.

This study shows the need for longitudinal research over a greater time period that addresses both micro- and macro-level factors to particularly gauge the impact of the macro factors beyond the two time points used in this analysis. A greater time period would also further test the veracity of both the micro- and macro-level findings.

From a policy perspective and for the provision of services, the challenges of reducing loneliness are immense, as we found many factors at the individual and country level affecting loneliness and change in loneliness in older-age. This suggests that initiatives to reduce loneliness should not only take place at the country level, but their introduction needs to be carefully planned, and take into consideration the individual characteristics locally in health, well-being and social networks, given the substantial role these play in explaining late-life loneliness.

Editors’ Postscript

Please note, like other contributions to this book, this chapter was written before the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020. The book’s introductory chapter (Chap. 1) and conclusion (Chap. 34) consider some of the key ways in which the pandemic relates to issues concerning social exclusion and ageing.

References

Aartsen, M., & Jylhä, M. (2011). Onset of loneliness in older adults: Results of a 28 year prospective study. European Journal of Ageing, 8(1), 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-011-0175-7.

Böger, A., & Huxhold, O. (2018). The changing relationship between partnership status and loneliness: Effects related to aging and historical time. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby153.

Börsch-Supan, A., Brandt, M., Hunkler, C., Kneip, T., Korbmacher, J., Malter, F., et al. (2013). Data resource profile: The survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe (SHARE). International Journal of Epidemiology, 42(4), 992–1001.

Cacioppo, J. T., & Cacioppo, S. (2018). The growing problem of loneliness. The Lancet, 391(10119). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30142-9.

Cohen-Mansfield, J., Hazan, H., Lerman, Y., & Shalom, V. (2016). Correlates and predictors of loneliness in older-adults: A review of quantitative results informed by qualitative insights. International Psychogeriatrics, 28(4), 557–576. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610215001532.

Courtin, E., & Knapp, M. (2017). Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: A scoping review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25(3), 799–812. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12311.

Dahlberg, L., Andersson, L., McKee, K. J., & Lennartsson, C. (2015). Predictors of loneliness among older women and men in Sweden: A national longitudinal study. Aging and Mental Health, 19(7), 409–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2014.944091.

De Jong Gierveld, J., & Van Tilburg, T. (2010). The De Jong Gierveld short scales for emotional and social loneliness: tested on data from 7 countries in the UN Generations and Gender Surveys. European Journal of Ageing, 7(2), 121–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-010-0144-6.

Dolberg, P., Shiovitz-Ezra, S., & Ayalon, L. (2016). Migration and changes in loneliness over a 4-year period: the case of older former Soviet Union immigrants in Israel. European Journal of Ageing, 13(4), 287–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-016-0391-2.

Dykstra, P. A. (2009). Older adult loneliness: Myths and realities. European Journal of Ageing, 6, 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-009-0110-3.

ESS Round 6: European Social Survey Round 6 Data. (2012). Data file edition 2.4. Norwegian Social Science Data Services, Norway – Data Archive and distributor of ESS data. http://nesstar.ess.nsd.uib.no/webview/. Accessed 19 Aug 2019.

ESS Round 7: European Social Survey Round 7 Data. (2014). Data file edition 2.2. Norwegian Social Science Data Services, Norway – Data Archive and distributor of ESS data. http://nesstar.ess.nsd.uib.no/webview/. Accessed 19 Aug 2019.

European Commission. (2012). Special Eurobarometer 393: Discrimination in the EU in 2012. Factsheets in English, 2012: https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Survey/getSurveyDetail/search/discrimination/surveyKy/1043. Accessed 30 Aug 2019.

European Commission. (2015). Special Eurobarometer 437: Discrimination in the EU in 2015. Factsheets in English, 2015: https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Survey/getSurveyDetail/search/disczAIimination/surveyKy/2077. Accessed 30 Aug 2019.

Fokkema, M., De Jong Gierveld, J., & Dykstra, P. A. (2012). Cross-national differences in older adult loneliness. The Journal of Psychology, 146(1–2), 201–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2011.631612.

Hansen, T., & Slagsvold, B. (2015). Late-life loneliness in 11 European countries: Results from the Generations and Gender survey. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1111-6.

Hansen, T., & Slagsvold, B. (2019). Et Øst-Vest skille for eldres livskvalitet i Europa? En sammenligning av ensomhet og depressive symptomer i 12 land (Vol. 33, pp. 74–90). Nordisk Østforum. https://doi.org/10.23865/noros.v33.1331.

Hawkley, L. C., & Kocherginsky, M. (2018). Transitions in loneliness among older adults: A 5-year follow-up in the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. Research on Aging, 40(4), 365–387.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352.

Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2004). A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Research on Aging, 26(6), 655–672.

Lykes, V. A., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2014). What predicts loneliness? Cultural difference between individualistic and collectivistic societies in Europe. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45, 468–490. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022113509881.

Nicolaisen, M., & Thorsen, K. (2014). Who are lonely? Loneliness in different age groups (18–81 years old), using two measures of loneliness. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 78(3), 229–257. https://doi.org/10.2190/AG.78.3.b.

Nyqvist, F., Nygård, M., & Scharf, T. (2019). Loneliness amongst older people in Europe: a comparative study of welfare regimes. European Journal of Ageing, 16(2), 133–143.

Pikhartova, J., Bowling, A., & Victor, C. (2016). Is loneliness in later life a self-fulfilling prophecy? Aging & Mental Health, 20(5), 543–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1023767.

Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2003). Risk factors for loneliness in adulthood and old age–A meta-analysis. In S. P. Shohov (Ed.), Advances in Psychology Research (Vol. 19, pp. 111–143). Hauppauge/New York: Nova Science Publishers.

Pronk, M., Deeg, D. J. H., Smits, C., van Tilburg, T. G., Kuik, D. J., Festen, J. M., & Kramer, S. E. (2011). Prospective effects of hearing status on loneliness and depression in older persons: Identification of subgroups. International Journal of Audiology, 50(12), 887–896. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992027.2011.599871.

Pronk, M., Deeg, D. J. H., Smits, C., Twisk, J. W., van Tilburg, T. G., Festen, J. M., & Kramer, S. E. (2014). Hearing loss in older persons: Does the rate of decline affect psychosocial health? Journal of Aging and Health, 26(5), 703–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264314529329.

Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Cutrona, C. E. (1980). The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(3), 472.

Steptoe, A., Shankar, A., Demakakos, P., & Wardle, J. (2012). Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(15), 5797–5801.

Stickley, A., Koyanagi, A., Roberts, B., Richardson, E., Abbott, P., et al. (2013). Loneliness: Its correlates and association with health behaviours and outcomes in nine countries of the former Soviet Union. PLoS One, 8(7), e67978. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0067978.

Sutin, A. R., Stephan, Y., Carretta, H., & Terracciano, A. (2015). Perceived discrimination and physical, cognitive, and emotional health in older adulthood. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(2), 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2014.03.007.

Swader, C. S. (2018). Loneliness in Europe: Personal and societal individualism-collectivism and their connection to social isolation. Social Forces, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soy088.

UNECE (2019). Active ageing index. https://statswiki.unece.org/display/AAI/Active+Ageing+Index+Home. Accessed 4 Oct 2019.

Walsh, K., Scharf, T., & Keating, N. (2017). Social exclusion of older persons: A scoping review and conceptual framework. European Journal of Ageing, 14(1), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-016-0398-8.

Weiss, R. S. (1973). Loneliness: the experience of emotional and social isolation. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Wilson, R. S., Krueger, K. R., Arnold, S. E., Schneider, J. A., Kelly, J. F., Barnes, L. L., et al. (2007). Loneliness and the risk of Alzheimer disease. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64, 234–240. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.64.2.234.

World Bank (2019). LAC equity lab: Income inequality – Inequality trends. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/lac-equity-lab1/income-inequality/inequality-trends. Accessed 4 Oct 2019.

Yang, K., & Victor, C. (2011). Age and loneliness in 25 European nations. Ageing & Society, 31, 1368–1388. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X1000139X.

Zaidi, A., Gasior, K., Hofmarcher, M. M., Lelkes, O., Marin, B., Rodrigues, R., Schmidt, A., Vanhuysse, P., & Zolyomi, E. (2013). Active ageing index 2012. Concept, methodology and final results. Vienna: European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research. https://statswiki.unece.org/display/AAI/V.+Methodology. Accessed 21 Sep 2019.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Morgan, D. et al. (2021). Revisiting Loneliness: Individual and Country-Level Changes. In: Walsh, K., Scharf, T., Van Regenmortel, S., Wanka, A. (eds) Social Exclusion in Later Life. International Perspectives on Aging, vol 28. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51406-8_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51406-8_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-51405-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-51406-8

eBook Packages: HistoryHistory (R0)