Abstract

The chapter gives an overview over the research on user comments in comments sections below online news items. It focuses on content analytic studies. It reviews the most important theoretical frameworks, research designs, and main constructs applied in investigations of user comments.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords:

1 Introduction

The digitalization and related socio-technological innovations enable online users to actively engage in the creation and distribution of online content. Alongside this development, the scholarly interest in user-generated content has established a flourishing and growing field of research (Naab and Sehl 2017). One of the most widespread forms of public user-generated content are user comments (Newman et al. 2019; Stroud et al. 2016). User comments originate when users take the opportunity to post written messages stimulated by a news item (e.g., news article or video). They are published either in comment sections on websites or on the social media pages of news outlets (e.g., Facebook page of Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung). As soon as more users engage in commenting on the same news item and referencing others’ comments, an online discussion develops (Ziegele and Quiring 2013). The news outlets provide a selection of topics along journalistic criteria that are relevant to society and reach a potentially large audience. At the same time, they retain the decision-making power over the user comments published in their comment sections and can moderate or delete undesired comments or limit the comment sections to selected topics (Weber 2014).

Research examines user comments from a broad variety of perspectives. It investigates content characteristics (see below), comment authors (e.g., Springer 2014), regulation practices of harmful content (e.g., Heldt 2019; Stroud et al. 2015; Ziegele et al. 2019), and journalists’ and editors’ engagement with user comments (e.g., Meyer and Carey 2014). In addition, scholars examine a multitude of effects of user comments on the readers’ attitudes towards topics (e.g., Sikorski 2016) and social issues (e.g., Hwang 2018), their evaluations of journalistic content and behaviors (e.g., Naab et al. 2020). Lastly, scholars in many subfields of communication science examine user comments on specific topics of their interests. This reflects the relevance of user-generated content in the users’ media repertoires (Newman et al. 2019) and the mounting evidence on the effects of user comments on attitudes and behaviors. Among these are studies in the realm of political communication (e.g., Blassnig et al. 2019), health communication (e.g., Holton et al. 2014), science communication (e.g., Koteyko et al. 2013; Kraker et al. 2014; Walter et al. 2018), and many others. Although user comments barely represent the opinion climate on issues, they are often used to assess the „pulse of the public debate“ (Douai and Nofal 2012, p. 269).

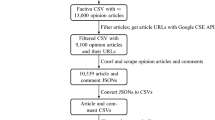

2 Common Research Designs of Content Analyses and Combinations of Methods

Mostly, scholars fathom user comments’ content characteristics with standardized methods: We find a multitude of standardized content analyses (see below) and a number of qualitative text analyses (e.g., on opinion dynamics on socially relevant topics, Al-Saggaf 2006; on discussion quality, Graham and Witschge 2003; on linguistic features applied during discussions, Küchler and Naab 2018; Neurauter-Kessels 2011). What is more, a growing number of studies investigates user comments with automated and semi-automated approaches (e.g., Gardiner et al. 2016; Stoll et al. 2020). The increasing importance of computational methods in communication research in recent years and the comparably easy access to large data sets of public content from social media sites contribute to this development (Possler et al. 2019). In the field of user comments, automated detection of incivility and other forms of offensive speech in user comments receive utmost attention. There are no systematic reviews of content analyses on user comments. However, in their scoping review of studies on user-generated content in general, Naab and Sehl (2017) reveal that standardized content analyses dominate over discourse analyses, text analyses, and further qualitative approaches.

Rarely, studies apply a combined approach (similarly, Naab and Sehl, 2017). For example, Graham and Wright (2015) combine a content analysis of online discussions with qualitative interviews with journalists. Ziegele et al. (2014) combine a content analysis of discussion factors in user comments with qualitative interviews with users.

Cross-sectional analyses clearly dominate over longitudinal analyses (similarly, Naab and Sehl 2017), but exceptions provide valuable insights (e.g., Gardiner et al., 2016; Kraker et al., 2014; Wright et al. 2020). Comparisons between cultures, countries, or language regions constitute a minority within the field of content analyses (Naab and Sehl 2017; for an exception see Ruiz et al. 2011).

In content analytic studies of user comments, several researchers investigate contextual influences. For instance, they examine the effects of the discourse architecture of the platform hosting the comment section. For this reason, they compare comment sections on news websites with those on news outlets’ social media pages (Rowe 2014; Ziegele et al. 2014) or compare comment sections with differences in user registration, anonymity, moderation strategies, ethical frameworks, and various technological features (Freelon 2015; Ksiazek 2015; Ruiz et al. 2011; Santana 2014). Another context factor of interest is the news item that attracts the comments. Yet most studies restrain themselves to the influence of journalistic features on the amount of comments (e.g., on the influence of news topics, Almgren and Olsson, 2015; Liu et al. 2015; Tenenboim and Cohen 2015; of news factors in the articles, Weber 2014; of the deliberative quality of the articles, Marzinkowski and Engelmann 2018).

With regard to sampling it is fair to state that user comments on Facebook pages catch overwhelming scholarly attention (Jünger, in prep.). This can be attributed to the development that many news outlets have shifted their comment sections to Facebook (Su et al. 2018) and that Facebook is still among the most widely used social media platforms for news consumption (Pew Research Center 2015). Furthermore, Facebook has provided comparably easy access to its public content in the past. Additional studies (often undertaken by journalism scholars) focus on comment sections on the websites of news outlets. Be that as it may, other platforms have received much less attention (see for exceptions, e.g., analyses of YouTube comments, Djerf-Pierre et al. 2019).

Very rarely, content analyses are conducted as part of experimental designs. For example, in a field experiment, Stroud et al. (2015) varied, who engaged with the users of a comment section. They analyzed the effects on the quality of the succeeding comments. In a few laboratory experiments, scholars manipulated comments in a thread and content analyzed the responses of their participants (e.g., Chen and Lu 2017; Naab 2020).

3 Theoretical Frameworks and Main Constructs

Regarding content characteristics of user comments, the most prevalent theoretical framework is deliberation theory (Freelon 2015). This strand of research analyzes how far online discussions come close to the normative ideal of deliberative discussions (often referring to the notions of deliberation by Barber 1984; Gastil 2008; Habermas 1989). It claims that deliberative online discussions should include diverse viewpoints; participants should present well-reasoned arguments on the substantial issue; discussions should provide equal opportunity to speak for all; participants should refer to one another reciprocally and consider the others’ arguments while being respectful and authentic.

Studies investigate the heterogeneity of views in comment sections and views complement to the standpoints offered in the news articles they accompany. While some researchers claim that comments complement the journalistic products (Baden and Springer 2014; Douai and Nofal 2012; Jakobs 2014), others are more skeptical and find that comments rarely contain alternative opinions or complementary standpoints (Noci et al. 2010; Toepfl and Piwoni 2015).

Analyses of user comments’ valence reveal that comments on websites and Facebook pages of news media outlets are predominantly adverse and critical (Coe et al. 2014). They criticize aspects such as a lack of facticity and impartiality (Prochazka and Schweiger, 2016).

Further, research indicates that online discussions can present well-reasoned arguments and facts (e.g., by citing sources to back up claims, Graham and Wright 2015). However, several studies suggest that emotions dominate online discussions (Jakobs 2014; Lilienthal et al. 2014; Loveland and Popescu 2011; Taddicken and Bund 2010).

The interactive character of online discussion through reciprocal exchange between participants is a further matter of many analyses: Scholars examine the amount of reply comments, references to other users, journalists, or the content of other comments (Graham and Wright 2015). Whether other users’ views are reflected, is also examined by analyzing if comments pose questions (Graham and Wright 2015; Manosevitch and Walker 2009). Interactivity is rather low, since comment authors exchange with others only to a limited extent and dialogues between authors end after a few comments (Jakobs 2014; Loveland and Popescu 2011; Noci et al. 2010; Singer 2009; Ziegele et al. 2014).

Overwhelming scholarly attention is devoted to the analysis of uncivil and otherwise disrespectful speech in user comments (on the term incivility, Papacharissi 2004). This is in line with public debates about detrimental effects of offensive content in social media and about opportunities to regulate such content. Several empirical investigations show, depending on their study design, their measurement of incivility, and sampling technique, that up to 50 percent of the comments include personal attacks, obscenities, racism, sexism, and other forms of offensive speech (Coe et al. 2014; Diakopoulos and Naaman 2011a, 2011b; Ksiazek 2015; Noci et al. 2010; Ruiz et al. 2011). Yet, researchers support that, at least at the beginning of comment threads, discussions are coherent and focus on the issue under debate (Belli et al. 2000; Graham and Wright 2015; Noci et al. 2010; Ruiz et al. 2011). User comments mostly are assessed as mediocrely comprehensible and correct in language, grammar, and style (Jakobs 2014).

Besides analyses that are (more or less explicitly) tied to the normative concept of deliberation, studies also consider so-called discussion factors in user comments. They follow the idea of news factors in journalists’ news selection and presentation (Galtung and Ruge 1965). Ziegele et al. (2014) argue that “specific message characteristics in user comments stimulate response comments from subsequent users” (p. 1114). Among these characteristics are controversy, personalization, uncertainty, unexpectedness, comprehensibility, and negativity.

Aside from the actual content of the user comments themselves, scholars also investigate assumptions about the authors of such comments. For example, they code the gender of authors (e.g., in studies on the relationship between author gender and writing or receiving incivility, Gardiner et al. 2016; Küchler et al. 2019) or the professional status of participants (e.g., in studies on the engagement of journalists in the comment sections, Jakobs 2014; Wright et al. 2020).

4 Research Desiderata

Despite the extensive empirical literature, it is advisable to point out some desiderata of the existing field of research: Most studies refer to online discussions in Western cultures and only rarely do scholars take the effort to compare findings across countries or cultures. In their sample selection, most studies refer to user comments in the comment sections of the most read news outlets. While this is understandable considering that these comments will also have greater reach and potential effects, it disregards potential deviations in comment sections of less popular outlets. These might also have different discourse architectures, readers, and commenting patterns. The generalizability of the findings is further limited because user comments on Facebook pages of news outlets receive overproportionate attention while other social media platforms like YouTube, TikTok, or Instagram are barely examined.

With regard to the dimensions under investigation, Freelon (2015) argues for a closer examination of normative frameworks besides deliberation theory such as liberal individualism or communitarianism. Additionally, many researchers focus on detecting and describing forms of incivility and related forms of disrespectful speech in comments. While the social significance of these studies is uncontested, it should not divert scholarly attention from further characteristics of online discussions.

Relevant Variables in DOCA – Database of Variables for Content Analysis

Arguments: https://doi.org/10.34778/5d

Clarity: https://doi.org/10.34778/5e

Number of reply comments: https://doi.org/10.34778/5f

References

Almgren, S. M., & Olsson, T. (2015). ‘Let’s get them involved’... to some extent: Analyzing online news participation. Social Media + Society, 1(2).

Al-Saggaf, Y. (2006). The online public sphere in the Arab world: The war in Iraq on the Al Arabiya website. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(1), 311–334.

Baden, C., & Springer, N. (2014). Com(ple)menting the news on the financial crisis: The contribution of news users’ commentary to the diversity of viewpoints in the public debate. European Journal of Communication, 29(5), 529–548.

Barber, B. (1984). Strong democracy. Participatory politics for a new age. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Belli, R. F., Schwarz, N., Singer, E., & Talarico, J. (2000). Decomposition can harm the accuracy of behavioural frequency reports. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 14(4), 295–308.

Blassnig, S., Engesser, S., Ernst, N., & Esser, F. (2019). Hitting a nerve: Populist news articles lead to more frequent and more populist reader comments. Political Communication, 36(4), 629–651.

Chen, G. M., & Lu, S. (2017). Online political discourse: Exploring differences in effects of civil and uncivil disagreement in news website comments. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 61(1), 108–125.

Coe, K., Kenski, K., & Rains, S. A. (2014). Online and uncivil? Patterns and determinants of incivility in newspaper website comments. Journal of Communication, 64(4), 658–679.

Diakopoulos, N., & Naaman, M. (2011a). Topicality, time, and sentiment in online news comments. In D. Tan (Ed.), Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1405–1410). New York, NY: ACM.

Diakopoulos, N., & Naaman, M. (2011b). Towards quality discourse in online news comments. In P. J. Hinds, J. C. Tang, J. Wang, J. Bardam, & N. Ducheneaut (Eds.), Proceedings of the ACM 2011 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (pp. 133–142). New York, NY: ACM.

Djerf-Pierre, M., Lindgren, M., & Budinski, M. A. (2019). The role of journalism on YouTube: Audience engagement with ‘superbug’ reporting. Media and Communication, 7(1), 235–247.

Douai, A., & Nofal, H. K. (2012). Commenting in the online Arab public sphere: Debating the Swiss minaret ban and the “Ground Zero Mosque” online. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 17(3), 266–282.

Freelon, D. (2015). Discourse architecture, ideology, and democratic norms in online political discussion. New Media & Society, 17(5), 772–791.

Galtung, J., & Ruge, M. H. (1965). The structure of foreign news: The presentation of the Congo, Cuba and Cyprus crises in four Norwegian newspapers. Journal of Peace Research, 2(1), 64–90.

Gardiner, B., Mansfield, M., Anderson, I., Holder, J., Louter, D., & Ulmanu, M. (2016). The dark site of Guardian comments. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/apr/12/the-dark-side-of-guardian-comments.

Gastil, J. (2008). Political communication and deliberation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Graham, T., & Witschge, T. (2003). In search of online deliberation: Towards a new method for examining the quality of online discussions. Communications, 28(2), 173–204.

Graham, T., & Wright, S. (2015). A tale of two stories from “below the line”. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 20(3), 317–338.

Habermas, J. (1989). The structural transformation of the public sphere. Cambridge: MIT.

Heldt, A. (2019). Reading between the lines and the numbers: An analysis of the first NetzDG reports. Internet Policy Review, 8(2).

Holton, A., Lee, N., & Coleman, R. (2014). Commenting on health: A framing analysis of user comments in response to health articles online. Journal of Health Communication, 19(7), 825–837.

Hwang, H., Kim, Y., & Kim, Y. (2018). Influence of discussion incivility on deliberation: An examination of the mediating role of moral indignation. Communication Research, 45(2), 213–240.

Jakobs, I. (2014). Diskutieren für mehr Demokratie [Discussing for more democracy]? In W. Loosen & M. Dohle (Eds.), Journalismus und (sein) Publikum [Journalism and (its) audience] (pp. 191–210). Wiesbaden: Springer.

Jünger, J. (in prep.). Die Macht der APIs. Online-Plattformen als Kontextfaktoren wissenschaftlicher Forschung [The power of APIs. Online platforms as context factors of scientific research]. In A. Kostiučenko & M. Kuhnhenn (Eds.), Die Macht des Kontextes [The power of context]. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Koteyko, N., Jaspal, R., & Nerlich, B. (2013). Climate change and ‘climategate’ in online reader comments: a mixed methods study. The Geographical Journal, 179(1), 74–86.

Kraker, J. de Kuijs, S., Cörvers, R., & Offermans, A. (2014). Internet public opinion on climate change: a world views analysis of online reader comments. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management, 6(1), 19–33.

Ksiazek, T. B. (2015). Civil interactivity: How news organizations’ commenting policies explain civility and hostility in user comments. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 59(4), 556–573.

Küchler, C., & Naab, T. K. (2018, November). User interactions during online conflict. Discussions in comment sections between norm negotiation, personal offenses, and fake profile accusations. Paper presented at conference of the European Communication Research and Education Association, Prag, Czechia.

Küchler, C., Stoll, A. Ziegele, M., & Naab, T. K. (2022). Gender-related differences in online comment sections: Findings from a large-scale content analysis of commenting behavior. Social Science Computer Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/08944393211052042.

Lilienthal, V., Weichert, S., Reineck, D., Sehl, A., & Worm, S. (2014). Digitaler Journalismus: Dynamik – Teilhabe – Technik [Digital journalism: Dynamic - participation - technology]. Schriftenreihe Medienforschung der Landesanstalt für Medien Nordrhein-Westphalen. Leipzig: Vistas.

Liu, Q., Zhou, M., & Zhao, X. (2015). Understanding news 2.0: A framework for explaining the number of comments from readers on online news. Information & Management, 52(7), 764–776.

Loveland, M. T., & Popescu, D. (2011). Democracy on the web. Information, Communication & Society, 14(5), 684–703.

Manosevitch, E., & Walker, D. (2009, April). Reader comments to online opinion journalism: A space of public deliberation. 10th International Symposium on Online Journalism, Austin, TX.

Marzinkowski, H., & Engelmann, I. (2018). Die Wirkung „guter“ Argumente [The effect of “good” arguments]. Publizistik, 63(2), 269–287.

Meyer, H. K., & Carey, M. C. (2014). In moderation. Journalism Practice, 8(2), 213–228.

Naab, T. K. (March, 2020). Effekte von Feedback-Kommentaren auf die Autor*innen bewerteter Nutzerkommentare [Effects of feedback comments on the authors of evaluated user comments]. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the German Communication Association, Munich, Germany.

Naab, T. K., Heinbach, D., Ziegele, M., & Grasberger, M.‑T. (2020). Comments and credibility: How critical user comments decrease perceived news article credibility. Journalism Studies, 216(4), 1–19.

Naab, T. K., & Sehl, A. (2017). Studies of user-generated content: A systematic review. Journalism, 18(10), 1256–1273.

Neurauter-Kessels, M. (2011). Im/polite reader responses on British online news sites. Journal of Politeness Research. Language, Behaviour, Culture, 7(2), 187–214.

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., & Kalogeropoulos, A. (2019). Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2019. Retrieved from https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/inline-files/DNR_2019_FINAL.pdf.

Noci, J. D., Domingo, D., Masip, P., Micó, J. L., & Ruiz, C. (2010). Comments in news, democracy booster or journalistic nightmare: Assessing the quality and dynamics of citizen debates in Catalan online newspapers. International Symposium on Online Journalism, 2(1), 46–64.

Papacharissi, Z. (2004). Democracy online: civility, politeness, and the democratic potential of online political discussion groups. New Media & Society, 6(2), 259–283.

Pew Research Center (2015, July 14). The evolving role of news on Twitter and Facebook. Retrieved from http://www.journalism.org/files/2015/07/Twitter-and-News-Survey-Report-FINAL2.pdf.

Possler, D., Bruns, S., & Niemann-Lenz, J. (2019). Data is the new oil - but how do we drill it? Pathways to access and acquire large data sets in communication science. International Journal of Communication, 13, 3894–3911.

Prochazka, F., & Schweiger, W. (2016). Medienkritik online: Was kommentierende Nutzer am Journalismus kritisieren [Media criticism online: What commenters criticize about journalism]. Studies in Communication and Media, 5(4), 454–469.

Rowe, I. (2014). Civility 2.0: A comparative analysis of incivility in online political discussion. Information, Communication & Society, 18(2), 121–138.

Ruiz, C., Domingo, D., Mico, J. L., Diaz-Noci, J., Meso, K., & Masip, P. (2011). Public sphere 2.0? The democratic qualities of citizen debates in online newspapers. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 16(4), 463–487.

Santana, A. D. (2014). Virtuous or vitriolic: The effect of anonymity on civility in online newspaper reader comment boards. Journalism Practice, 8(1), 18–33.

Sikorski, C. von (2016). The effects of reader comments on the perception of personalized scandals: Exploring the roles of comment valence and commenters’ social status. International Journal of Communication, 10, 4480–4501.

Singer, J. B. (2009). Separate spaces: Discourse about the 2007 Scottish elections on a national newspaper web site. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 14(4), 477–496.

Springer, N. (2014). Beschmutzte Öffentlichkeit?: Warum Menschen die Kommentarfunktion auf Online-Nachrichtenseiten als öffentliche Toilettenwand benutzen, warum Besucher ihre Hinterlassenschaften trotzdem lesen, und wie die Wände im Anschluss aussehen [Soiled public?: Why people use the commentary function on online news sites as a public toilet wall, why visitors read their legacies anyway, and what the walls look like afterwards]. München: Lit.

Stoll, A., Ziegele, M., & Quiring, O. (2020). Detecting impoliteness and incivility in online discussions: Classification approaches for German user comments. Computational Communication Research, 2(1), 109–134.

Stroud, N. J., Scacco, J. M., Muddiman, A., & Curry, A. L. (2015). Changing deliberative norms on news organizations’ Facebook sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 20(2), 188–203.

Stroud, N. J., van Duyn, E., & Peacock, C. (2016). Survey of commenters and comment readers. Retrieved from https://mediaengagement.org/research/survey-of-commenters-and-comment-readers/.

Su, L. Y.‑F., Xenos, M. A., Rose, K. M., Wirz, C., Scheufele, D. A., & Brossard, D. (2018). Uncivil and personal? Comparing patterns of incivility in comments on the Facebook pages of news outlets. New Media & Society, 20(10), 3678–3699.

Taddicken, M., & Bund, K. (2010). Ich kommentiere, also bin ich. Community Research am Beispiel des Diskussionsforums der ZEITOnline [I comment, therefore I am. Community research using the example of the ZEITOnline discussion forum]. In M. Welker & C. Wünsch (Eds.), Die Online-Inhaltsanalyse. Forschungsobjekt Internet [The online content analysis. Research object ‚internet‘] (pp. 167–190). Köln: von Halem.

Tenenboim, O., & Cohen, A. A. (2015). What prompts users to click and comment: A longitudinal study of online news. Journalism, 16(2), 198–217.

Toepfl, F., & Piwoni, E. (2015). Public spheres in interaction: Comment sections of news websites as counterpublic spaces. Journal of Communication, 65(3), 465–488.

Walter, S., Brüggemann, M., & Engesser, S. (2018). Echo chambers of denial: Explaining user comments on climate change. Environmental Communication, 12(2), 204–217.

Weber, P. (2014). Discussions in the comments section: Factors influencing participation and interactivity in online newspapers’ reader comments. New Media & Society, 16(6), 941–957.

Wright, S., Jackson, D., & Graham, T. (2020). When journalists go “below the line”: Comment spaces at The Guardian (2006–2017). Journalism Studies, 21(1), 107–126.

Ziegele, M., Breiner, T., & Quiring, O. (2014). What creates interactivity in online news discussions? An exploratory analysis of discussion factors in user comments on news items. Journal of Communication, 64(6), 1111–1138.

Ziegele, M., Naab, T. K., & Jost, P. (2019). Lonely together? Identifying the determinants of collective corrective action against uncivil comments. New Media & Society, 10. Advanced online publication. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819870130.

Ziegele, M., & Quiring, O. (2013). Conceptualizing online discussion value. A multidimensional framework for analyzing user comments on mass-media websites. In E. L. Cohnen (Ed.), Communication Yearbook 37 (pp. 125–153). New York, NY: Routledge.

Funding

This research was funded by the German Research Foundation, Grant NA 1281/1-1, project number 358324049

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access Dieses Kapitel wird unter der Creative Commons Namensnennung 4.0 International Lizenz (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de) veröffentlicht, welche die Nutzung, Vervielfältigung, Bearbeitung, Verbreitung und Wiedergabe in jeglichem Medium und Format erlaubt, sofern Sie den/die ursprünglichen Autor(en) und die Quelle ordnungsgemäß nennen, einen Link zur Creative Commons Lizenz beifügen und angeben, ob Änderungen vorgenommen wurden.

Die in diesem Kapitel enthaltenen Bilder und sonstiges Drittmaterial unterliegen ebenfalls der genannten Creative Commons Lizenz, sofern sich aus der Abbildungslegende nichts anderes ergibt. Sofern das betreffende Material nicht unter der genannten Creative Commons Lizenz steht und die betreffende Handlung nicht nach gesetzlichen Vorschriften erlaubt ist, ist für die oben aufgeführten Weiterverwendungen des Materials die Einwilligung des jeweiligen Rechteinhabers einzuholen.

Copyright information

© 2023 Der/die Autor(en)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Naab, T.K., Küchler, C. (2023). Content Analysis in the Research Field of Online User Comments. In: Oehmer-Pedrazzi, F., Kessler, S.H., Humprecht, E., Sommer, K., Castro, L. (eds) Standardisierte Inhaltsanalyse in der Kommunikationswissenschaft – Standardized Content Analysis in Communication Research. Springer VS, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-36179-2_37

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-36179-2_37

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer VS, Wiesbaden

Print ISBN: 978-3-658-36178-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-658-36179-2

eBook Packages: Social Science and Law (German Language)