Abstract

The study of culture in media or mediated culture—referred to here as the study of cultural coverage—often makes use of content analysis to build up a more systematized knowledge of possibly evolving patterns that can only be observed by gathering certain amounts of data over a certain period of time. Typically, content analysis is employed to trace the anatomy of the mediated culture, either as hierarchies of artistic forms or of as a representation of a specific cultural phenomenon. Content analysis is also applied to identify the mechanisms of mediation and follow their evolution over time, i.e., cultural change.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The study of culture in media or mediated culture—referred to here as the study of cultural coverage—often makes use of content analysis to build up a more systematized knowledge of possibly evolving patterns that can only be observed by gathering certain amounts of data over a certain period of time. Typically, content analysis is employed to trace the anatomy of the mediated culture, either as hierarchies of artistic forms (Schmutz 2009; Stegert 1998) or of as a representation of a specific cultural phenomenon (Roosvall and Widholm 2018; Janssen et al. 2008). Content analysis is (see e.g. Krippendorff 2004) also applied to identify the mechanisms of mediation (Jaakkola 2015; Szántó et al. 2004; Shrum, 1991) and follow their evolution over time, i.e., cultural change (Purhonen et al. 2019, p. 2). Typically, these dimensions––mediated culture, arts and cultural phenomena, journalistic genres and discourses as well as their change––are interwoven and incorporated in the same study design, even if the emphasis on these three dimensions varies.

Content analysis of cultural coverage requires an underlying “theory” of culture to guide the systematic dissection of the fundamental components of what is referred to as “culture.” This is not always an easy task; as Raymond Williams (2011, p. 76) remarked, “culture” is one of the most complicated words in the modern English language. Appropriately enough, in their classic study, Kroeber and Kluckhohn (1952) identified over 200 definitions of the concept. In its most basic meaning, however, “culture” refers to the cultivation of the mind, and this process of cultivation takes on a wide variety of different manifestations in different contexts (Williams 2011). This chapter delimits “cultural coverage” by focusing on the cultural journalistic content, thus leaving content analyses on cultural phenomena in journalistic content of any type (including general news) beyond the scope, which could, following a broad definition, also be referred to as “cultural coverage”.

Journalism has adopted an operative definition, in which coverage has been used to refer to content typically classified as “arts and culture”: literature, music, performing arts, fine arts, photography, architecture, aesthetics, lifestyle issues, and so on. This classification has become established as a result of the organizational differentiation of editorial sectors in newspapers and other news outlets (Tuchman 1978; Forde 2003), in which “culture” has typically referred to anything that cannot be assigned to any other sections, such as “politics,” “economy,” or “international.” Cultural coverage can be divided into arts, culture, and entertainment journalism (Kristensen 2019). Arts or cultural journalism is a specialized form of journalism with the most limited scope, with a focus on a limited area of an art form, such as literature or a certain type of music (e.g., classical music or a subgenre), typically published in the distinct section labeled “Arts and Culture,” “Feuilleton,” or simply “Culture.” When culture is defined more broadly to cover lifestyle and entertainment issues, such as celebrity news, media, and everyday cultures, the coverage, often seen as an extension of the core cultural coverage, can be referred to—depending on the newspaper and country—as current affairs, lifestyle, entertainment, or popular journalism (Hanusch 2013). Culturally-oriented journalism is produced by generalists within general (news) journalism, for example, whenever a cultural aspect is activated in political, economic, or local journalistic content (e.g., in op-eds) (see Jaakkola 2015.) Therefore, cultural events can also be traced in general news coverage that reaches beyond cultural journalism (see e.g., Low 2012). The most common understanding of cultural coverage, however, has been to limit it to the specialized forms, where the news sections or organizational structure provide the delimitation.

Instead of taking a general perspective on journalistic coverage, content analysis can also be carried out on more limited subtypes of cultural journalism, delimiting the object of inquiry to one cultural form or genre only. Examples include music journalism (Bruhn Jensen and Larsen 2010; Koreman 2014), film journalism (Kersten and Janssen 2016), and lifestyle journalism (Kristensen and From 2012). Furthermore, studies may focus on the critique of a certain cultural form, such as, for example, performance art reviews (Shrum 1991), art reviews (Heikkilä and Gronow 2018), film reviews (Baumann 2007), music reviews (Connes and Jones 2014; van Venrooij and Schmutz 2010), or food and restaurant reviews (Johnston and Baumann 2015; Kobez 2016). These studies make it easier for the researcher to deepen into academic study discipline and enable a more nuanced study of subgenres.

Furthermore, culture is created and maintained in very different production contexts that offer different methodological options for the researcher. Professionally generated content (PGC) differs from the more established concept of user-generated content (UGC). PGC often refers to journalistic content, while user-generated content is the result of cultural “produsage” (content-producing engagement) by ordinary cultural citizens and consumers (Bruns 2016). The division between professionals and amateurs has always been porous in cultural journalism, in which an extensive group of producers have been freelancers. In the digital landscape, the grades of professionalism and amateurism are even harder to distinguish (see e.g. Leadbeater and Miller 2004).

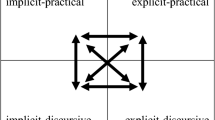

Based on the above, we can summarize that there are four different distinctions that mark the anatomy of cultural coverage and are thus of relevance when designing content analyses specifically on cultural coverage:

-

Cultural form: What type of culture does the content represent—high, popular, or everyday culture? A certain cultural form (film, literature, theatre, architecture, etc.)?

-

Media form: What type of media is the cultural content published in—newspapers, online newspapers, magazines, online, television, radio, social media?

-

Journalistic form: What type of journalism or journalistic genre does the cultural content represent—fact-based or opinionated, or news-oriented journalism or criticism (reviewing)?

-

Production form: What type of production does the cultural content originate from—are the producers professional salary-paid staff journalists or freelancers, or professionals or amateurs?

The study of cultural coverage is essentially scattered across different cultural spheres, media types, and scientific disciplines, which affects the emphases and understandings of “culture.”1 Mediated culture is analyzed in qualitative means in many ways across different disciplines in social sciences and the humanities, such as, for example, in literary theory and criticism, performance and visual studies, art history, media and cultural studies, ethnology, and anthropology. These disciplines have less often employed quantitative methodology to capture the structures of culture.

2 Common Research Designs

Culture differs from other news content in that the reality it describes is doubly mediated: the object that the cultural coverage mediates is already a mediation of a reality. This doubly-mediated reality is not as contingent as in non-cultural news, but the yearly cycle of news topics follows the schematized “pseudo-events” produced by cultural institutions (Kepplinger 2016). For example, festivals, book releases, and seasonal concert tours occur at certain points in time and make one cultural form dominate over others. Media may also have special structures for following certain forms of culture in a systematic way, e.g., thematic pages, regularly published supplements, or journalistic formats dedicated to a single art form. The seasonal and editorial patterns may cause significant bias if consecutive weeks are used as a sampling method. This is why the seasonal variation has to be eliminated, for example, by using the constructed week in sampling (Riffe et al. 1993).

Content analyses, primarily in newspapers, are related to four overarching research questions: 1) What is the extension of cultural content (the amount of exposure of culture or a certain type of cultural coverage)?; 2) What is understood as “culture” (the concept of culture)?; 3) How is “culture” mediated by journalistic means (the genres or the means of presentation)?; and 4) Pertinent to all the previous questions, how have these constants developed over time (the assessment of cultural change)? The studies in which content analysis is applied to cultural coverage can roughly be divided into questions of the concept of culture, means of representation and representation of a cultural phenomenon.

These questions are to a high extent embedded in the theory of cultural intermediation (see, e.g., Bourdieu 1993; Jones et al. 2019), inquiring about the types of mediated arts or culture that the producers of cultural coverage foster as tastemakers, gatekeepers, and active producers of meaning and taste. Studies identifying the manifested cultural concept are often located in aesthetics (e.g. van Venrooij, A., and Schmutz 2010), arts or cultural sociology (e.g. Purhonen et al. 2019), or studies of a certain cultural form, such as film or television (e.g. Baumann 2007), and in these works the mediated culture itself is the object of inquiry.

The means of representation refer to the genres, styles, and modes of reporting (Jaakkola 2015; Wahl-Jorgensen 2013). These studies heavily draw on journalism and media studies, in which fields of scholarly inquiry have emerged within the study of arts and cultural journalism (Purhonen et al. 2019; Jaakkola 2015; Kristensen 2010), lifestyle journalism (Hanusch 2013; Kristensen and From 2012), and (particularly women’s) magazine journalism (Ytre-Arne 2012; Johnston and Swanson 2003). Both the intermediation and means of representation studies are often coupled with questions of professional identity and organizational cultures, which also provide a possibility to explore new and emerging identities in blogs and other online platforms, in particular with regard to amateur production (Jaakkola 2018, 2019, 2020, 2022; Kammer 2015; Verboord 2010, 2012).

The representations of a cultural phenomenon are less concerned with the special character of cultural journalism itself, focusing on selected cases of mediated arts or culture, for example, through selecting units of analyses that constitute the representations of cultural phenomena, organizations, persons, personal attributes, or reception of works, related to reception studies, an attempt to understand artistic works’ “changing intelligibility by identifying the—interpretative assumptions that give them meaning for different audiences at different periods” (Culler 1981, p. 13). These studies are motivated by the diverse interests of the scientific disciplines within which they are developed and thus constitute a very heterogeneous group. Typical cultural phenomena examined include art pieces; culture and entertainment, such as individual films and television series (Kristensen et al. 2017; Sparre and From 2017); cultural changes and phenomena, such as globalization or cultural diversity (Roosvall and Widholm 2018; Janssen et al. 2008; Lefrançois and Éthier 2019; Berkers et al. 2014); as well as prizes, competitions, and events (Leppänen 2015; Reason and García 2007; Wahl-Jorgensen 2013). Research on cultural content can also even be driven by questions of extra-artistic topics such as media violence (Gerbner 1972; Smythe 1954), or, for example, social problems (Pitman and Stevenson 2015). Questions of ethnicity, minority and gender, like in the case of “Black lives matter” and “Me too” campaigns, have typically been studied across different genres of journalism, including the cultural content (Elmasry and el-Nawawy 2017; Askanius and Hartley 2019).

All of the above studies have predominantly focused on the culture pages of daily print newspapers (Jaakkola 2015; Kristensen and From 2011; Lund 2005; Reus and Harden 2005, 2015). The bias towards printed journalism may have developed because of the pragmatic questions of access, but also by the fact that cultural journalism in the dailies has had a tradition of strongly focusing on the written word. Moreover, as content analysis was developed in an era when printed mass media dominated (for the cultural area, see e.g., Gerbner 1969) and the study of cultural journalism emerged from ambitions of mapping leading newspapers’ culture articles in terms of their underlying concept of culture (e.g., Schulz 1970; Sörbom 1982; Titchener 1969; Varpio 1982). Fewer studies have focused on broadcasting (Hellman et al. 2017; Skara 2012; Monière 1999; see also Lejre and Kristensen 2014) and the study of professionally produced cultural content in online newspapers and digital platforms is still very much in its infancy (Santos Silva 2019).

Much of the content analysis on printed cultural journalism has been connected to national cultural public spheres. Longitudinal analyses have been conducted, for example, in the Nordic countries (Hurri 1993; Jaakkola 2015; Kristensen and From 2011; Larsen 2008; Lund 2005; Purhonen et al. 2019; Riegert and Widholm 2019), Continental Europe (Janssen 1999; Reus and Harden 2005, 2015; Stegert 1998), Eastern and Central European countries (Kõnno et al. 2012), Hispanic countries (Moreira 2005; Santos Silva 2019; da Silva and Santos Silva 2014), and the U.S. (Janeway and Szántó 2003; Szántó et al. 2004). Nevertheless, during the recent decade the comparative intention has significantly grown, putting forward transnational study designs (Bruhn Jensen and Larsen 2010; Heikkilä and Gronow 2018; Janssen et al. 2008; Janssen et al. 2011; Jubin 2010; Kersten and Janssen 2016; Kõnno et al. 2012; Purhonen et al. 2019; Schmutz et al. 2010; Venrooij and Schmutz 2010; Verboord and Janssen 2015). Through a comparison between journalistic cultures and cultural spheres, preferably between media systems that most starkly differ from each other, national characteristics are better highlighted.

In general, the results of the content-analytic studies have formed an important counterweight to arguments on crises of journalism (Alexander et al. 2016) or moral panics (Drotner 1999). The crisis discourse has become prolific in public discussions and debates on cultural journalism (see, e.g., Jaakkola 2015), with many scholars’ research interests, in fact, being motivated by this specific aspect (see, e.g., Knapskog and Larsen 2008; Kristensen and From 2011; Purhonen et al. 2019; Reus and Harden 2005, 2015; Sarrimo 2017; Widholm et al. 2019). In a similar fashion, studies on mediated violence have played a significant role for the emergence of content analysis of media (Gerbner 1972; Smythe 1954). As shown in the next section, analyses do not entirely or at all support the narratives of declining quantity and quality of journalism or the negative impacts of harmful content that are frequently cited in media. Content analyses over time have shown that developments in content are slower and structures are more constant than what is observed in the everyday.

3 Main Constructs

The amount of media exposure dedicated to culture within a newspaper is relevant because the space dedicated to culture can be regarded as a sign of respect and acknowledgement of the culture beat in the news organization. Quantitative content analyses in Northern European newspapers show that the volume of cultural content within a newspaper has generally expanded during the past decades, even if articles have become shorter (Jaakkola 2015; Purhonen et al. 2019). American newspapers suffered heavy cuts at the turn of the millennium (NAJP 1999).

Though the general interest cultural coverage has typically been focused on highbrow content and described as elitist, content analyses indicate that the forms of culture has gradually become more inclusive during the past decades. This “opening-up thesis” is supported both by the gradual incorporation of more popular art forms into the cultural concept, such as popular and niche forms of art and everyday culture (Purhonen et al. 2019). The aesthetic classification systems have thus legitimized art forms that were previously left outside the journalistic canon (Venrooij 2009). Moreover, the representational means have become more diverse. Print papers have adopted more contingent, newspaper-specific formats to address culture, using more images and visual elements of storytelling (Santos Silva 2019). According to the “generalization” or “newsification” thesis (Jaakkola 2015; Sarrimo 2017; Widholm et al. 2019), newspapers have also adopted a more news-oriented approach, which has led to investments in the development of reporting in the news genre and emphasis on descriptive rather than evaluative content. However, the subjective, emotional, and interpretative element can still be seen in cultural reporting, differentiating it from hard news reporting (Riegert and Widholm 2019). Some content analyses have also traced sourcing practices, finding that the share of commercial ready-made content has increased in cultural journalism (Strahan 2010), or included author attributes, such as gender and employment, in the analyses (Jaakkola 2015; Verboord 2012).

4 Research Desiderata

Content analyses focusing on one media channel only, for example the culture pages in the printed newspapers, are increasingly running the risk of losing sight of the overall picture, as many culture sections nowadays place the monitoring of entire cultural forms (such as film) or genres (reviews) online or in cultural supplements. With increased convergence between media channels and organizations, future studies should more carefully take into account the transmedia and cross-platform editorial strategies of journalistic production.

Content analysis has potential for paving the way for problematizing the use of hegemonic cultural concepts and de-westernizing media research, a call made by journalism scholars (Curran and Park 1999; Wasserman and de Beer 2009) by putting different journalistic and cultural parameters in comparison. There are many geo-cultural areas in the world where the professional cultural coverage has not yet been systematically studied. Even national cultural public spheres encompass many layers, such as minority, sub-, and diasporic cultures, which should be studied further. Emerging and alternative forms of cultural coverage should also be more systematically examined, including professionally and semi-professionally produced online content in blogs and other online platforms. The analyses of user-generated content should be explored with the same kind of questions as have been applied to legacy media content, to find out how the cultural online producers challenge or parallel professional cultural coverage, oscillating between institutionalized and non-institutionalized production environments and creating new presentation forms, hierarchies, and preferences. It is evident that mixed methods research designs, ranging from conventional to automatized content analysis and integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches, are becoming increasingly more relevant for capturing the manifold mediations of culture.

Notes

-

1.

Some delimitations regarding references in this chapter: Content analysis is a widely applied method in Master’s theses, but these references are excluded. The same applies for conference papers. English-language studies are preferred over studies written in national languages, complemented by some relevant studies in German, French, Spanish, and Scandinavian languages.

Relevant Variables in DOCA—Database of Variables for Content Analysis

Forms of culture: https://doi.org/10.34778/2x

Journalistic genre: https://doi.org/10.34778/2y

Author byline: https://doi.org/10.34778/2z

References

Alexander, J. W., Butler Breese, E., & Luengo, M. (Eds.). (2016). The crisis of journalism reconsidered: Democratic culture, professional codes, digital future. Cambridge University Press.

Askanius, T., & Hartley, J. M. (2019). Framing gender justice: A comparative analysis of the media coverage of #metoo in Denmark and Sweden. Nordicom Review, 40(2), 19–36.

Baumann, S. (2007). Hollywood highbrow: From entertainment to art. Princeton University Press.

Berkers, P.P.L., Janssen, M.S.S.E., & Verboord, M. (2014). Assimilation into the literary mainstream? The classification of ethnic minority authors in newspaper reviews in the United States, the Netherlands and Germany. Cultural Sociology, 8(1), 25–44.

Bourdieu, P. (1993). The field of cultural production: Essays on art and literature. Polity Press.

Bruhn Jensen, K., & Larsen, P. (2010). The sounds of change: Representations of music in European newspapers 1960–2000. In J. Gripsrud & L. Weibull (Eds.), Media, markets & public spheres (pp. 249–266). Intellect.

Bruns, A. (2016). User-generated content. In: Jensen, K.B., Craig, R.T., Pooley, J.D. & Rothenbuhler, E.W. (eds.), The international encyclopedia of communication theory and philosophy. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 1–5.

Conner, T., & Jones, S. (2014). Art to commerce: The trajectory of popular music criticism. IASPM—Journal of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music, 4(2), 7–23.

Culler, J. (1981). The pursuit of signs: Semiotics, literature, deconstruction. Routledge.

Curran, J., & Park, M.-J. (1999). De-westernizing media studies. Routledge.

da Silva, M. T., & Santos Silva, D. (2014). Trends and transformations within cultural journalism: A case study of newsmagazine Visão. OBS*, 8(4), 171–185.

Drotner, K. (1999). Dangerous media? Panic discourses and dilemmas of modernity. Paedagogica Historica: International Journal of the History of Education, 35(3), 593–619.

Elmasry, M. H., & el-Nawawy, M. (2017). Do black lives matter? A content analysis of New York Times and St. Louis Post-Dispatch coverage of Michael Brown protests. Journalism Practice, 11(7), 857–875.

Forde, E. (2003). Journalists with a difference: Producing music journalism. In S. Cottle (Ed.), Media organization and production (pp. 113–130). Sage Publications.

Gerbner, G. (1969). Towards “cultural indicators”: The analysis of mass mediated public message systems. Communication Review, 17(2), 137–148.

Gerbner, G. (1972). The violence profile: Some indicators of trends in and the symbolic structure of network television drama 1967–1971. U.S. Government’s printing office.

Hanusch, F. (Ed.). (2013). Lifestyle journalism. Routledge.

Heikkilä, R., & Gronow, J. (2018). Stability and change in the style and standards of European newspapers’ arts reviews, 1960–2010. Journalism Practice, 12(5), 624–639.

Hellman, H., Larsen, L. O., Riegert, K., Widholm, A., & Nygaard, S. (2017). What is cultural news good for? Finnish, Norwegian, and Swedish cultural journalism in public service organisations. In N. N. Kristensen & K. Riegert (Eds.), Cultural journalism in the Nordic countries (pp. 111–133). Nordicom.

Hurri, M. (1993). Kulttuuriosasto: symboliset taistelut, sukupolvikonflikti ja sananvapaus viiden pääkaupunkilehden kulttuuritoimituksissa 1945–80. [Cultural desk: Symbolic struggles, generational conflict, and freedom of speech in five culture desks of capital-based dailies 1945–80.] Doctoral dissertation. University of Tampere.

Jaakkola, M. (2015). The contested autonomy of arts and journalism: Change and continuity in the dual professionalism of cultural journalism. Tampere University Press.

Jaakkola, M. (2018). Vernacular reviews as a form of co-consumption: User-generated review videos on YouTube. MedieKultur—Journal of Media and Communication Research, (34)65, 10–30.

Jaakkola, M. (2019). From re-viewers to me-viewers: The #Bookstagram review sphere on Instagram and the perceived uses of the platform and genre affordances. Interactions: Studies in Communication and Culture, 10(1–2), 91–110.

Jaakkola, M. (2020, in press). Useful creativity: Vernacular reviewing on the video-sharing platform Vimeo. Culture Unbound.

Jaakkola, M. (2022). Reviewing culture online: Post-institutional cultural critique across platforms. Palgrave Macmillan.

Janeway, M., & Szántó, A. (2003). Arts, culture, and media in the United States. The Journal of Arts Management, Law and Society, 32(4), 279–292.

Janssen, S. (1999). Art journalism and cultural change: The coverage of the arts in Dutch newspapers 1965–1990. Poetics 26(5–6), 329–348.

Janssen, S., Kuipers, G., & Verboord, M. (2008). Cultural globalization and arts journalism: The international orientation of arts and culture coverage in Dutch, French, German, and U.S. newspapers, 1955 to 2005. American Sociological Review, 73(5), 719–740.

Janssen, S., Verboord, M., & Kuipers, G. (2011). Comparing cultural classification: High and popular arts in European and U.S. elite newspapers. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 63(51), 139–168.

Johnston, D. D, & Swanson, D. H. (2003). Undermining mothers: A content analysis of the representation of mothers in magazines. Mass Communication and Society, 6(3), 243–265.

Johnston, J., & S. Baumann (2015). Foodies: Democracy and distinction in the gourmet foodscape (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Jones, B., Perry, B., & Long, P. (Eds.). (2019). Cultural intermediaries connecting communities: Revisiting approaches to cultural engagement. Policy Press.

Jubin, O. (2010). Experts without expertise? Findings of a comparative study of American, British and German-language reviews of musicals by Stephen Sondheim and Andrew Lloyd Webber. Studies in Musical Theatre, 4(2), 185–197.

Kammer, A. (2015). Post-industrial cultural criticism: The everyday amateur expert and the online cultural public sphere. Journalism Practice, 9(6), 872–889.

Kepplinger, H.M. (2016). Pseudo‐event. In G. Mazzoleni (Ed.), The International Encyclopedia of Political Communication.

Kersten, A., & Janssen, S. (2016). Trends in cultural journalism: The development of film coverage in cross-national perspective, 1955–2005. Journalism Practice, 11(7), 840–856.

Knapskog, K., & Larsen, L. O. (Eds.). (2008). Kulturjournalistikk: pressen og den kulturelle offentligheten [Cultural journalism: The press and the cultural public sphere]. Scandinavian Academic Press.

Kobez, M. (2016). The illusion of democracy in online consumer restaurant reviews. International Journal of E-Politics, 7(1), 54–65.

Kõnno, A., Aljas, A., Lõhmus, M., & Kõuts, R. (2012). The centrality of culture in the 20th century Estonian press: A longitudinal study in comparison with Finland and Russia. Nordicom Review, 33(2), 103–117.

Koreman, R. (2014). Legitimating local music: Volksmuziek, hip-hop/rap and dance music in Dutch elite newspapers. Cultural Sociology, 8(4), 501–519.

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Kristensen, N. N. (2010). The historical transformation of cultural journalism. Northern Lights: Film and Media Studies Yearbook, 8(1), 69–92.

Kristensen, N. N. (2019). Arts, culture and entertainment coverage. In T. P. Vos & F. Hanusch (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of journalism studies. Wiley-Blackwell.

Kristensen, N. N., & From, U. (2011). Kulturjournalistik: journalistik om kultur [Cultural journalism: Journalism on culture]. Samfundslitteratur.

Kristensen, N. N., & From, U. (2012). Lifestyle journalism: Blurring boundaries. Journalism Practice, 6(1), 26–41.

Kristensen, N. N., Hellman, H., & Riegert, K. (2017). Cultural mediators seduced by Mad Men: How cultural journalists legitimized a quality TV series in the Nordic region. Television & New Media, 20(3), 257–274.

Kroeber, A. L., & Kluckhohn, C. (1952). Culture: A critical review of concepts and definitions. Meridian Books.

Larsen, L. O. (2008). Forskyvninger. Kulturdekningen i norske dagsaviser 1964–2005 [Displacements: Cultural coverage in Norwegian dailies 1964–2005]. In K. Knapskog & L.O. Larsen (Eds.), Kulturjournalistikk: pressen og den kulturelle offentligheten (pp. 283–329). Scandinavian Academic Press.

Leadbeater C., & Miller, P. (2004). The pro-am revolution: How enthusiasts are changing our society and economy. Demos.

Lefrançois, D., & Éthier, M.-A. (2019). Slāv: une analyse de contenu médiatique centrée sur le concept d’appropriation culturelle [Slāv: A media content analysis focused on the concept of cultural appropriation]. Revue de recherches en littératie médiatique multimodale, 9. https://doi.org/10.7202/1062035ar

Lejre, C., & Kristensen, N. (2014). En kvantitativ metode til analyse af radio [A quantitative method for analysing the radio]. MedieKultur—Journal of Media and Communication Research, 30(56), 151–169.

Low, D. (2012). Content analysis and press coverage: Vancouver’s Cultural Olympiad. Canadian Journal of Communication, 37(3), 505–512.

Lund, C. W. (2005). Kritikk og kommers: kulturdekningen i skandinavisk dagspresse [Criticism and commerce: Cultural coverage in the Scandinavian daily press]. Universitetsforlaget.

Monière, D. (1999). Démocratie médiatique et representation politique: analyse comparative de quatre journaux télévisés: Radio-Canada, France 2, RTBF (Belgique) et TSR (Suisse) [Mediated democracy and political representation: A comparative analysis of four television news channels: Radio-Canada, France 2, RTBF (Belgium) and TSR (Switzerland)]. Les presses de l’Université de Montréal.

Moreira, S. V. (2005). Trends and new challenges in journalism research in Brazil. Brazilian Journalism Research, 1(2).

NAJP (1999). Reporting the arts (I): News coverage of arts and culture in America. National Arts Journalism Program (NAJP).

Pitman, A., & Stevenson, F. (2015). Suicide reporting within British newspapers’ arts coverage. Crisis, 36, 13–20.

Purhonen, S., Heikkilä, R., Karademir Hazir, I., Lauronen, T., Rodríguez, C. F., & Gronow, J. (2019). Enter culture, exit arts? The transformation of cultural hierarchies in European newspaper culture sections, 1960–2010. Routledge.

Reason, M., & García, B. (2007). Approaches to the newspaper archive: Content analysis and press coverage of Glasgow’s Year of Culture. Media, Culture & Society, 29(2), 304–331.

Reus, G., & Harden, L. (2005). Politische ”Kultur”: Eine Längsschnittanalyse des Zeitungsfeuilletons von 1983 bis 2003 [Political ‘culture’: A longitudinal analysis of culture pages, 1983–2003]. Publizistik, 50(2), 153–172.

Reus, G., & Harden, L. (2015). Noch nicht mit der Kunst am Ende [Not yet the end of arts]. Publizistik, 60, 205–220.

Riegert, K., & Widholm, A. (2019). The difference culture makes: Comparing Swedish news and cultural journalism on the 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris. Nordicom Review, 40(2), 3–18.

Riffe, D., Aust, C. F., & Lacy, S. R. (1993). The effectiveness of random, consecutive day and constructed week sampling in newspaper content analysis. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 70(1), 133–139.

Roosvall, A., & Widholm, A. (2018). The transnationalism of cultural journalism in Sweden: Outlooks and introspection in the global era. International Journal of Communication, 12(2018), 1431–1451.

Santos Silva, D. (2019). Digitally empowered: New patterns of sourcing and expertise in cultural journalism and criticism. Journalism Practice, 13(5), 592–601. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2018.1507682.

Sarrimo, C. (2017). The press crisis and its impact on Swedish arts journalism: Autonomy loss, a shifting paradigm and a “journalistification” of the profession. Journalism, 18(6), 664–679.

Schmutz, V. C. (2009). The classification and consecration of popular music: Critical discourse and cultural hierarchies. [Doctoral dissertation, Erasmus University Rotterdam.]

Schmutz, V., van Venrooij, A., Janssen, S., & Verboord, M. (2010). Change and continuity in newspaper coverage of popular music since 1955: Evidence from the United States, France, Germany, and the Netherlands. Popular Music and Society, 33(4), 505–515.

Schulz, W. (Ed.). (1970). Der Inhalt der Zeitungen: eine Inhaltsanalyse der deutschen Tagespresse in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (1967) mit Quellentexten früher Inhaltsanalysen in Amerika, Frankreich und Deutschland [The content of the newspapers: A content analysis of the German daily press in the German Republic (1967) with source texts from early content analyses in America, France and Germany]. Düsseldorf.

Shrum, W. (1991). Critics and publics: Cultural mediation in highbrow and popular performing arts. American Journal of Sociology, 97(2), 347–375.

Skara, M. (2012). Analysis of Radiofeuilleton and the themes of its “Thema.” [A European Journalism-Fellowship thesis, Freie Universität Berlin.]

Smythe, D. W. (1954). Reality as presented by television. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 18(2), 143–156.

Sparre, K., & From, U. (2017). Journalists as tastemakers: An analysis of the coverage of the TV series Borgen in a British, Swedish and Danish newsbrand in the Nordic Countries. In N. N. Kristensen & K. Riegert (Eds.), Cultural journalism in the Nordic countries (pp. 159–178). Nordicom.

Stegert, G. (1998). Feuilleton für alle: Strategien im Kulturjournalismus der Presse [Feuilleton for all: Strategies in cultural journalism of the daily press]. Max Niemeyer Verlag.

Strahan, L. (2010). Sources of arts journalism: Who’s writing the arts pages? In B. Franklin & M. Carlson (Eds.), Journalists, sources, and credibility: New perspectives (pp. 127–138). Routledge.

Sörbom, G. (Ed.). (1982). Forskningsprojektet Kritik och konst [The research project Criticism and the arts]. University of Uppsala.

Szántó, A., Levy, D. S., & Tyndall, A. (Eds.). (2004). Reporting the arts II: News coverage of arts and culture in America. National Arts Journalism Program (NAJP).

Titchener, C. B. (1969). A content analysis of B-values in entertainment criticism. [Doctoral Dissertation in Mass Communication, Ohio State University.]

Tuchman, G. (1978). Making news: A study in the construction of reality. Free Press.

van Venrooij, A. (2009). The aesthetic discourse space of popular music: 1985–86 and 2004–05. Poetics, 37(4), 315–332.

van Venrooij, A., & Schmutz, V. (2010). The evaluation of popular music in the United States, Germany and the Netherlands: A comparison of the use of high art and popular aesthetic criteria. Cultural Sociology, 4(3), 395–421.

Varpio, Y. (Ed.). (1982). Kirjallisuuskritiikki Suomessa 2: kirjallisuuskritiikin väyliä ja rakenteita [Literary criticism in Finland 2: Channels and structures of literary criticism]. Kirjastopalvelu.

Verboord, M. (2010). The legitimacy of book critics in the age of the Internet and omnivorousness: Expert critics, Internet critics and peer critics in Flanders and the Netherlands. European Sociological Review, 26(6), 623–637. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcp039

Verboord, M. (2012). Exploring authority in the film blogosphere: Differences between male and female bloggers regarding blog content and structure. Interactions: Studies in Communication and Culture, 2(3), 243–259.

Verboord, M., & Janssen, J. (2015). Arts journalism and its packaging in France, Germany, the Netherlands and the United States, 1955–2005. Journalism Practice, 9(6), 829–852.

Wahl-Jorgensen, K. (2013). The strategic ritual of emotionality: A case study of Pulitzer Prize-winning articles. Journalism, 14(1), 129–145.

Wasserman, H., & de Beer A. S. (2009). Towards de-westernising journalism studies. In K. Wahl-Jorgensen & T. Hanitzsch (Eds.), The handbook of journalism studies (pp. 448–458). Routledge.

Widholm, A., Riegert, K., & Roosvall, A. (2019). Abundance or crisis? Transformations in the media ecology of Swedish cultural journalism over four decades. Journalism. Advance online publication August, 6. Journalism. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919866077

Williams, R. (2011). Keywords: A vocabulary of culture and society. Routledge. (Original work published 1976).

Ytre-Arne, B. (2012). Women’s magazines and their readers: Experiences, identity and everyday life. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Bergen.]

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access Dieses Kapitel wird unter der Creative Commons Namensnennung 4.0 International Lizenz (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de) veröffentlicht, welche die Nutzung, Vervielfältigung, Bearbeitung, Verbreitung und Wiedergabe in jeglichem Medium und Format erlaubt, sofern Sie den/die ursprünglichen Autor(en) und die Quelle ordnungsgemäß nennen, einen Link zur Creative Commons Lizenz beifügen und angeben, ob Änderungen vorgenommen wurden.

Die in diesem Kapitel enthaltenen Bilder und sonstiges Drittmaterial unterliegen ebenfalls der genannten Creative Commons Lizenz, sofern sich aus der Abbildungslegende nichts anderes ergibt. Sofern das betreffende Material nicht unter der genannten Creative Commons Lizenz steht und die betreffende Handlung nicht nach gesetzlichen Vorschriften erlaubt ist, ist für die oben aufgeführten Weiterverwendungen des Materials die Einwilligung des jeweiligen Rechteinhabers einzuholen.

Copyright information

© 2023 Der/die Autor(en)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Jaakkola, M. (2023). Content Analysis in the Research Field of Cultural Coverage. In: Oehmer-Pedrazzi, F., Kessler, S.H., Humprecht, E., Sommer, K., Castro, L. (eds) Standardisierte Inhaltsanalyse in der Kommunikationswissenschaft – Standardized Content Analysis in Communication Research. Springer VS, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-36179-2_20

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-36179-2_20

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer VS, Wiesbaden

Print ISBN: 978-3-658-36178-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-658-36179-2

eBook Packages: Social Science and Law (German Language)