Abstract

A major goal of natural history museums (NHMs) is to shape visitors’ worldviews about science allowing them to learn about the research process, its characteristics, and the people behind it. In this context, developing visitors’ understanding of the nature of science (NOS) is an underlying educational objective. To date, little is known about how, if at all, museum guides integrate NOS during guided tours while addressing visitor expriences. The current research attempted to fill this lacuna by studying the views of NHM guides with a focus on tours about ecological and evolutionary topics. The research participants were museum guides (n = 15) working in four NHMs in Israel. The study used a qualitative approach. Data were gathered using semi-structured interviews in which the guides were asked to reflect retrospectively on their practices during guided tours. Utilizing the content analysis method, the data were analyzed through the lens of the family resemblance approach to NOS and visitors’ satisfying experiences in museums. The study’s findings revealed that museum guides refer primarily to the visitors’ cognitive experiences while integrating mainly epistemic-cognitive aspects of NOS.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Theoretical Background

Understanding nature’s animate and inanimate parts will help us face local and global challenges, such as environmental deterioration, loss of biological variability, and climate change. Therefore, natural history is a necessary component of biological education (King & Achiam, 2017). Natural History Museums (NHMs) are considered important natural history learning environments due to the research, educational, and curating activities that take place there. NHMs’ collections present visitors with natural history’s essential content, practices, and discourse in a tangible form (Marandino et al., 2015). NHMs present both the history of nature and related scientific research and, in this sense, shape visitors’ views of scientific activity and the scientific community. Thus, natural history museums have a distinctive advantage in promoting evolution education (Diamond & Evans, 2007; King & Achiam, 2017; Piqueras et al., 2022) and education on ecology-related topics, such as environmental issues (King & Achiam, 2017), climate change (McGhie et al., 2018), etc. NHMs have a critical role in making science, knowledge, and the narratives that facilitate the accessibility of scientific learning to the public, as they are research institutions that interact with a diverse audience (Mujtaba et al., 2018). As centers of informal education, NHMs are open to all ages, to a wide range of cultures, and to all walks of society. They also have the power to contribute to the education of citizens who have science capital and base their decisions on scientific knowledge. One of the means of communication between the scientific community and the public is through NHM exhibits (Achiam et al., 2014). To establish visitors’ connection to the science presented in the exhibits, it is crucial to highlight the intricacy of scientific processes and social implications (Hine & Medvecky, 2015). This approach can contribute to shaping the visitors’ understanding of the nature of science (NOS).

NOS refers to the fundamental aspects of science, such as its definition, methodology, ability to address certain types of questions, and limitations in addressing others. One of the frameworks for science education that incorporates NOS is the Family Resemblance Approach (FRA), which was proposed by Erduran and Dagher (2014) and builds upon the framework established by Irzik & Nola (2011). The development of FRA was based on overlaps, similarities, and differences among the scientific disciplines. The FRA highlights that NOS has cognitive-epistemic and social-institutional aspects which depend on each other, and cannot exist without each other. Together, these aspects portray a comprehensive picture of science and underline its vital importance. Each aspect is followed by categories that describe the various characteristics of the sciences. The epistemic-cognitive aspects include the categories of aims and values, practices, methods and methodological rules, and scientific knowledge. The categories of social-institutional aspects are: professional activities, scientific ethos, social certification and dissemination, social values of science, social organizations and interactions, political power structures, and financial systems (Erduran & Dagher, 2014). Recently, Irzik & Nola (2022) proposed a new category to be added to the social-institutional aspects of NOS: the reward system of science. Only a few studies have examined the context of NOS in NHMs (e.g., Piqueras et al., 2022). These studies indicate that visitors’ direct interaction with the exhibits they are exposed to in NHMs may contribute to their understanding of several aspects of NOS. Along with their contribution to visitors’ understanding of NOS, visits to NHMs may generate rewarding, memorable and satisfying experiences (Pekarik et al., 1999; Tsybulskaya & Camhi, 2009). In the professional literature, it is noted that positive experiences for museum visitors can be classified into four categories: object experiences (originate from encounters with significant exhibit objects), cognitive experiences (originate from interpretive or intellectual opportunities provided by the experience), introspective experiences (originate from private perceptions and experiences) and social experiences (originate from social engagement). These experiences are uniquely able to engage visitors with the content discussed and may influence the process of the development of understanding of NOS during the guided tour.

Many studies in the field of informal education have focused on visitors and their learning outcomes (Achiam et al., 2016; Bamberger & Tal, 2007, 2008; Nesimyan-Agadi & Ben Zvi Assaraf, 2021; Piqueras et al., 2008; Shaby et al., 2019b; Tal & Morag, 2007). Recent studies have shown increased awareness of the importance of the guides in these environments (Pshenichny-Mamo & Tsybulsky, 2023), and have focused on guides’ professional development (Lederman & Holliday, 2017; Piqueras & Achiam, 2019; Tran & King, 2007, 2011) and the interactions between guides and visitors (Pattison & Dierking, 2013; Plummer et al., 2021; Shaby et al., 2019a). Despite the fact that guides – as educators – play a key role in connecting the museum’s agenda with the needs and interests of its visitors, and are essential in designing museum visitors’ experiences (Tran, 2007), the research largely overlooks their perspectives. The goal of this study was to examine guides’ views regarding the integration of NOS, with attention to visitor satisfaction, during instruction on relevant biological topics in the areas of ecology and evolution. The decision to focus on the context of topics pertaining to ecology and evolution stemmed from the importance of NHMs to the didactics of biological topics. Similar to King and Achiam (2017), we too believe that it is necessary to develop comprehensive natural history education in order to develop a well-rounded understanding of science. Natural history education encompasses a thorough understanding of plants and animals in their current and historical natural environments, as well as the scientific methods and practices used in the field. Such an education would provide learners with the necessary knowledge, skills, and reasoning abilities to actively engage in discussions and initiatives related to biological issues, such as evolution and ecology.

2 Methods

This was a qualitative study involving 15 guides working in four different NHMs located in various regions in Israel. We chose the term “guides”, as is customary in the Hebrew language, to refer to paid employees at the museum who accompany and guide visitors through exhibitions and galleries in the museum (Bamberger & Tal, 2008; Tsybulskaya & Camhi, 2009). The guides were approached via a request to the manager of education programs at each museum, who helped to put the primary researcher in contact with the guides. The guides who agreed to participate in the study did so on a voluntary basis. The guides were diverse in terms of their number of years of experience as museum guides, hours worked per week, academic degree, and gender (10 women and 5 men).

Data were collected using individual semi-structured interviews, which were recorded and transcribed. In the interviews, the guides were asked to describe their practice during guided tours from a reflective and retrospective point of view. Examples of questions asked during the interviews are: (1) How do you refer to the characteristics of science and scientific research during your guidance? (2) What are the topics of the guided tours at the museum? What are the main points in these guided tours, and how do you relate to them?

The data were then submitted for content analysis from the perspective of FRA (Erduran & Dagher, 2014), with the addition of the social-institutional aspect reward system (Irzik & Nola, 2022) and satisfying visitors’ experiences (Pekarik et al., 1999; Tsybulskaya & Camhi, 2009; Tsybulsky, 2019). The analysis was performed in three stages. In the first stage, after the transcription and repeated reading of interviews, the analysis focused on expressions related to cognitive-epistemic and social-institutional aspects of NOS. After that, in the second stage, statements identified as connected to aspects of NOS were categorized into four categories that describe the visitors’ experiences: object experiences, cognitive experiences, introspective experiences, and social experiences. The third stage included analysis of guides’ phrases related to evolutionary or ecological topics.

During data analysis, our aim was to identify the primary aspect of NOS in the guides’ utterances. However, in some cases it was not feasible to pinpoint a single primary aspect, as certain statements touched upon multiple aspects of NOS. Thus, a single statement might encompass mentions of various NOS aspects.

In the following, we illustrate the process of data analysis using several examples:

-

Utterances such as “[...] the most that I use is some stories about Darwin [...]” were not included in the analysis. Although the above includes a reference to evolution, it does not refer to any NOS aspects or any of the categories of visitors’ experiences.

The following utterance was included in our analysis:

It is important to me to make the other person feel like a researcher. To make him think, for example, about how Darwin, who lived in a time when there was not so much technology, had to look at all the animals and imagine the evolutionary connection between them in his mind’s eye. And really, when I try to connect these things, I’m more trying to connect through explaining that research is something that develops, it progresses, and things that we once knew are different today; today we know better. It’s something that I think really, really characterizes my work as a guide when it comes to elements of research.

This guide talks about Darwin’s thinking process and the development of scientific knowledge in the context of evolution. She refers to the tentativeness of scientific knowledge, an epistemic-cognitive aspect of NOS, and science as a human endeavor, a social-institutional aspect of NOS. This is also a good example of the way in which a single utterance from a guide can relate to several aspects of NOS. With this utterance, the guide tries to get visitors to connect to Darwin’s journey and imagine how research was done in the days when technological instruments were less developed than they are today. In doing so, she essentially tries to evoke emotions and to give the visitors an opportunity to imagine a different time from the one in which we live today, thus relating to the visitors’ introspective experiences.

3 Findings

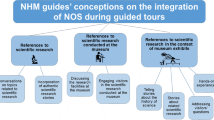

Our findings indicated that out of 173 references related to NOS aspects, 57 were in the context of evolution and ecology. We found that the museum guides addressed NOS mostly in terms of epistemic-cognitive aspects (43 utterances), and less in terms of social-institutional aspects (14 utterances). In the context of the museum visitors’ experience, most of the utterances reflected cognitive experiences together with epistemic-cognitive aspects of NOS (10 utterances). The guides tended to reflect less on the social experiences of museum visitors. Only one guide reflected on this experience in the context of social-institutional NOS aspects. The rest of the findings are shown in Figs. 6.1 and 6.2.

The flow chart shows the distribution of epistemic-cognitive aspects of NOS mentioned by the guides into categories linked to visitors’ experience and topic (the number of references appears in parentheses). The total number of references to epistemic-cognitive aspects is higher than the total number of references to visitor experience, as a single guide’s utterance encompasses mentions of various NOS aspects in several cases

3.1 Epistemic-Cognitive Aspects of NOS

3.1.1 Cognitive Experiences

In the context of evolution, one guide talks about aspects of NOS by mentioning that scientific knowledge is tentative and changes with new findings. In her words, the guide tries to enrich visitors’ understanding of the way in which we gain scientific knowledge. Thereby, she references the cognitive experience of the museum visitors:

I like to talk about the aspects of archeological findings. If the subject is “What Makes Us Human?” I talk about Homo erectus, which was believed to be the first evidence of a hominid walking upright and not a human being as we know it today. And years later, Australopithecus afarensis, known as Lucy, was discovered: a species that was much more ancient and able to walk upright. Then suddenly, the scientific world looks at it in astonishment and realizes that they made a mistake and so all the books need to be changed. That is part of the beauty of science; there is this great humility to say we were wrong, but look – now we know something new and much more significant, and who knows what else we will discover? It is always possible to un-prove what those before me found. And there is always room for doubt.

Another reference to the cognitive experience of museum visitors was made by a guide who talked about the ecology-related issue of stream pollution. While mentioning that scientists observe things and test their observations, he made a reference to the epistemic-cognitive aspect of scientific practices related to NOS. The guide aims to enhance visitors’ understanding of how research on stream pollution is conducted and facilitates their acquisition of new information and knowledge:

[…] I think that the museum guide has an important role in making science accessible […] It’s very important that people understand more than just the bottom line. It’s not enough to point and say that the streams in Israel are polluted; rather, they need to understand the research being done, how it is conducted, and that people are, in fact, working on this issue.

3.1.2 Object Experiences

One guide refers to ecology in the context of a food chain exhibit. The guide draws attention to an exhibit showcasing pellets derived from owl food, which serves as a basis for discussing the underlying scientific principles. He underscores the extensive research and experimentation involved in acquiring scientific information and highlights that the museum researchers engage in such studies. The focus on the visitors’ object experience is apparent as they see “the real thing”- the food that the owl consumed presented in its real form. These are also the authentic objects that researchers study in the museum. By guiding visitors to observe the exhibit in detail, the guide highlights its distinctiveness:

[…] There are numerous exhibits highlighting research, specifically how the research is conducted. One example of such exhibits is the owl pellet display, where visitors can observe the disassembly of pellets like a puzzle. These are things that are connected to the studies done at the museum. And these are also things that draw people’s attention, people suddenly go see this table with a lot of partridges that look very bad (pellets), they’re just spread out there, and they don’t understand why it’s displayed like that, and that’s precisely the point that gives us an opening to talk about the research and why it’s like that, what goes on behind the curtains […].

Another guide talks about the technique of ringing birds as one of a variety of scientific methods that serve scientists in ecological research. The guide discusses multiple aspects of object experiences. First, she allows visitors to see “the real thing” – an exhibit that shows an authentic research method currently in use in ecological research. Second, she shows them an exhibit that illustrates the transition – from hunting animals in order to research them, to the use of research methods that do not include hunting, but rather the tracking of living animals. Thus, the guide shows visitors an important exhibit that they are likely to find meaningful:

We have a ringed stork. That’s a point where I can start talking about everything related to research, including from the past few years, about ringing and tracking migratory birds. The general direction is to take some exhibit and talk about it. Say, to talk about the development of research of bird migration, how it started with ringing, how it looks today, you know… something entirely different […].

This guide also notes that she integrates discussion of scientific research, and the nature thereof, by using exhibits, and thus emphasizes her attention to the visitors’ object experiences.

3.1.3 Introspective Experiences

In the context of plant ecology, one of the guides mentions studies that were done in the museum’s laboratory focused on incubator-like products. She notes that visitors may overlook their existence despite passing by every day. The guide mentions NOS, saying that science is a way of knowing. Attention is shown to the visitors’ introspective experience in the attempt to reflect visitors’ memories of this fruit body – did they ever notice it? She also emphasizes the significance of the fruit body as a subject of research:

One researcher here deals with the product that develops when a plant mosquito bites a plant and a kind of fruit body is created – like an incubator. These incubators are hard for people to imagine, although they may pass by it every day. And I can tell them that a few floors above, a researcher is studying in her laboratory how this thing affects the ecology of the plants.

3.2 Social-Institutional Aspects of NOS

3.2.1 Cognitive Experiences

The guide discusses the cognitive experience of visitors and describes how he enriches their knowledge about the dance of honeybees. This topic is related to communication in the world of honeybees, which falls under the category of ecology. The guide highlights that the discovery of the honeybee dance earned a Nobel Prize for the researcher, which relates to the social-institutional aspect of NOS, specifically the reward system.

[…] For example, I talk about the bees’ dance and about communication in the world of bees. Then I mention the researcher Karl von Frisch, who discovered the bees’ dance and won a Nobel prize […].

3.2.2 Object Experiences

One of the guides discusses the divergent evolution of partridges in different regions of Israel, highlighting science as a human effort noting that the findings presented in the exhibits are the work of researchers. Thus, she mentions the social-institutional aspects of NOS. Additionally, the guide draws attention to the visitors’ object experiences, as they are able to see the partridges that underwent divergent evolution and observe authentic objects from nature that were used in the research:

In one of our galleries we have a collection of partridges from the south and partridges from the north, and you can see the differences. So I can talk about that, and I can show them, ‘look, this is what researchers found, this is the process (divergent evolution) that operates on a lot of animals, it’s not just partridges, it’s also tigers, it’s rabbits,’ and I explain the topic. It’s something that really connects to research done by scientists here […].

3.2.3 Introspective Experiences

A guide mentions respect for the environment – which falls under the scientific ethos aspect of NOS – while speaking about the state of the environment as an ecological issue. In her words, she tries to get visitors to connect to the problem that exists and to reflect by recalling past ideas and experiences which may be less harmful to the environment:

Regarding ecology, I think it is essential to talk about how we brought on this environmental situation. The most critical exhibition for understanding this is “The Human Impact”. This exhibition shows the effects of the changes we have made as a result of a very difficult process of industrialization and its consequences. [...] many people are trying to find technological solutions, such as substitutes. I think it’s a good idea, but we also need to find solutions for the harm that we have caused and go back to the less harmful ways used in the past.

Another guide discusses the importance of respecting nature in the context of ecological problems, highlighting it as a core social value of science. Specifically, she focuses on the issue of species extinction and aims to raise visitors’ awareness and encourage introspection. By prompting visitors to reflect on the meaning of the exhibit and encouraging them to feel a spiritual connection to the issue, she hopes to inspire them to carry this knowledge with them into the future. Through this approach, she engages with the introspective experiences of visitors, inviting them to consider their own values and actions in relation to the environment:

[…] I try to alert visitors to the fact that the animal they are observing is at risk of becoming extinct, that the other animal they were observing has already become extinct, and that the animals that they see in their natural environment are also at risk of becoming extinct. I try to show them that this is directly related to their everyday lives. I emphasize that there is something they can do about it, which is to ask questions even after they leave the museum.

3.2.4 Social Experiences

In the following interview, the guide emphasizes the social values of science in the context of ecology. He introduces visitors to the collection of Father Ernst Johann Schmitz and sparks a conversation on the topic of respecting the environment. This topic is discussed in connection with the research method of hunting animals that was commonly used in the past. The guide aims to generate a group discussion about the impact of these methods and the importance of ethical considerations in scientific research. In this way, he attends to the social experience of museum visitors by creating a shared activity related to the exhibit and fostering social learning:

Say, the exhibit of Father Schmitz, there we talk about him and about the fact that all of ecology and zoology was based on hunting, and people are really horrified, ‘People who researched animals hunted them?’ And then I try to start a discussion, a shared learning.

4 Conclusions and Discussion

This study explored the views of NHM guides regarding the integration of NOS aspects, while attending to museum visitors’ satisfying experiences, when discussing topics related to evolution and ecology. Our study found that when guiding visitors through the museum and addressing evolution and ecology topics, the guides tend to emphasize the epistemic-cognitive aspects of NOS. Also, they pay attention primarily to the cognitive experiences of visitors in the museum. We believe these findings complement each other. When the guides integrate aspects of NOS in the epistemic-cognitive context, they try to educate their audience about the characteristics of science and the scientific process. Thus, in essence, the guides usually relate to visitors’ cognitive experience during their time at the museum, allowing the visitors to gain new information and knowledge that enriches the previous understanding they may have had of various topics in evolution and ecology.

Through attention to the objects in an exhibit, the guides relate to the visitors’ object experiences. Attention to this experience is shown primarily through giving visitors the opportunity to see “real things” in terms of the authenticity of the object for scientific research. Similarly, this experience allows museum visitors to see objects that are rare and highly valuable to the world of science, and perhaps to be amazed by the various exhibits in the museum. Our findings support the view presented by King and Achiam (2017) that exhibits in NHMs can serve as “windows” into the practice of natural history and can enhance science education, especially biology education, for visitors. Additionally, our study indicates that the object experiences provided by guides during museum tours can expose visitors to both the epistemic-cognitive and social-institutional aspects of NOS.

Attention to introspective experiences during museum tours occurs primarily in the context of stories about the history of science in which the guides lead visitors to identify with the researcher’s story and imagine the spirit of the times in which he or she was active. Furthermore, these stories reveal the human component of science and scientific research, which has a direct connection to the social-institutional aspects of NOS. This exposure can enhance visitors’ understanding of these aspects. The introspective experiences enable visitors to recall their own past experiences at different points during the tour and to feel how these experiences take on new meaning within the context of the museum. Additionally, our findings suggest that when museum guides prompt visitors’ introspective experiences, it can result in visitors becoming aware of previously unfamiliar aspects of scientific research and knowledge. This heightened awareness can then deepen visitors’ understanding of the epistemic-cognitive aspects of NOS, which in turn can lead to a reinterpretation of the exhibits viewed during the guided tour.

Museum visitors’ social experience was mentioned in the interviews by only one guide, who spoke about the subject of ecology and mentioned a social-institutional aspect of NOS – social values of science. We believe that during the tours the guides do pay attention to visitors’ social experience, by creating a discussion between visitors or conducting one-on-one discussions related to ecology or evolution issues at various points. It could be that during their narrations the guides ask the visitors questions or answer their questions about scientific knowledge, or conversations arise about the struggles that the scientists faced during their scientific path. These interactions provide opportunities for visitors to discuss relevant NOS aspects and gain additional relevant knowledge. However, during the interviews, the guides did not share many of these situations. We may interpret this as indicating that they did not find these situations to be suitable answers to the questions we asked.

Prior research in informal education environments has suggested that interactions between museum guides and visitors primarily consist of technical explanations (Shaby et al., 2019a). However, our study offers new insight by revealing that, from the viewpoint of the guides themselves, there is an effort to engage with visitors in a manner that extends beyond simply explaining how to operate exhibits or objects. Instead, guides aim to enhance visitors’ overall experience at the NHMs and integrate aspects of NOS by incorporating relevant scientific knowledge, and knowledge about science related to ecology and evolution issues. Moreover, the interviews with the guides show that the efforts to integrate different aspects of NOS into the tours are done in an attempt to enhance visitors’ overall museum experience. Bamberger and Tal (2008) suggested that the expertise and passion exhibited by guides may play a role in the positive interactions between guides and visitors, which may contribute to their heightened engagement in the learning process during the tour. Our findings show that the guides tend to incorporate anecdotes and narratives that capture visitors’ interest and encourage their participation in the content being presented. Ultimately, the guides’ efforts serve to enrich and enliven the museum experience for visitors.

According to Holliday and Lederman’s (2014) findings, guides in informal educational settings possess a deep understanding of NOS. Our study builds on this conclusion by demonstrating that these guides also possess the pedagogical knowledge required to effectively integrate NOS into their guided tours. This knowledge includes a focus on visitors’ satisfying experiences, which are valued for their ability to inform and shape visitors’ expectations and preferences during museum visits or activities (Pekarik et al., 1999).

In conclusion, the focus of this study is on museum guides and their views. The objective is to gain a better understanding of the role of guides during the guided tours they give to museum visitors, building upon previous studies (Pshenichny-Mamo & Tsybulsky, 2023; Shaby et al., 2019a; Tran, 2007). Acquiring a deeper understanding of the diverse practices used in NHMs can aid museum educational staff in improving the design of educational programs and guide training programs that integrate evolutionary and ecological content and explicit instruction on NOS. This can facilitate the development of tours and exhibits that provide visitors with more satisfying and meaningful experiences, while enhancing visitors’ comprehension of different aspects of NOS. A follow-up study should examine these findings in comparison with what happens in practice during guided tours and in comparison with the experiences reported by the visitors themselves during these tours. Therefore, conducting observations of guided tours and examining interactions and visitors’ experiences with a focus on the integration of NOS could provide more insights and build upon our findings.

References

Achiam, M., May, M., & Marandino, M. (2014). Affordances and distributed cognition in museum exhibitions. Museum Management and Curatorship, 29(5), 461–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2014.957479

Achiam, M., Simony, L., & Lindow, B. E. K. (2016). Objects prompt authentic scientific activities among learners in a museum programme. International Journal of Science Education, 38(6), 1012–1035. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2016.1178869

Bamberger, Y., & Tal, T. (2007). Learning in a personal context: Levels of choice in a free choice learning environment in science and natural history museums. Science Education, 91(1), 75–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.20174

Bamberger, Y., & Tal, T. (2008). Multiple outcomes of class visits to natural history museums: The students’ view. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 17(3), 274–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-008-9097-3

Diamond, J., & Evans, E. M. (2007). Museums teach evolution. Evolution, 61(6), 1500–1506. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00121.x

Erduran, S., & Dagher, Z. R. (2014). Reconceptualizing the nature of science for science education. Springer.

Hine, A., & Medvecky, F. (2015). Unfinished science in museums: A push for critical science literacy. Journal of Science Communication, 14(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.22323/2.14020204

Holliday, G. M., & Lederman, G. N. (2014). Informal science educators’ views about nature of scientific knowledge. International Journal of Science Education, Part B, 4(2), 123–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/21548455.2013.788802

Irzik, G., & Nola, R. (2011). A family resemblance approach to the nature of science for science education. Science & Education, 20(7), 591–607. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-010-9293-4

Irzik, G., & Nola, R. (2022). Revisiting the foundations of the family resemblance approach to nature of science: Some new ideas. Science & Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-022-00375-7

King, H., & Achiam, M. (2017). The case for natural history. Science & Education, 26(1–2), 125–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-017-9880-8

Lederman, J. S., & Holliday, G. M. (2017). Addressing nature of scientific knowledge in the preparation of informal educators. In P. G. Patrick (Ed.), Preparing informal science educators: Perspectives from science communication and education (pp. 509–525). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-50398-1_25

Marandino, M., Achiam, M., & de Oliveira, A. D. (2015). The diorama as a means for biodiversity education. In S. D. Tunnicliffe & A. Scheersoi (Eds.), Natural history dioramas: History, construction and educational role (pp. 251–266). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9496-1_19

McGhie, H., Mander, S., & Underhill, R. (2018). Engaging people with climate change through museums. In W. Leal Filho, E. Manolas, A. M. Azul, U. M. Azeiteiro, & H. McGhie (Eds.), Handbook of climate change communication (Vol. 3, pp. 329–348). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-70479-1_21

Mujtaba, T., Lawrence, M., Oliver, M., & Reiss, M. J. (2018). Learning and engagement through natural history museums. Studies in Science Education, 54(1), 41–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057267.2018.1442820

Nesimyan-Agadi, D., & Ben Zvi Assaraf, O. (2021). How can learners explain phenomena in ecology using evolutionary evidence from informal learning environments as resources? Journal of Biological Education, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/00219266.2021.1877784

Pattison, S. A., & Dierking, L. D. (2013). Staff-mediated learning in museums: A social interaction perspective. Visitor Studies, 16(2), 117–143.

Pekarik, A. J., Doering, Z. D., & Karns, D. A. (1999). Exploring satisfying experiences in museums. Curator, 42(2), 152–173.

Piqueras, J., & Achiam, M. (2019). Science museum educators’ professional growth: Dynamics of changes in research–practitioner collaboration. Science Education, 103(2), 389–417. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21495

Piqueras, J., Hamza, K. M., & Edvall, S. (2008). The practical epistemologies in the museum: A study of students’ learning in encounters with dioramas. Journal of Museum Education, 33(2), 153–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/10598650.2008.11510596

Piqueras, J., Achiam, M., Edvall, S., & Ek, C. (2022). Ethnicity and gender in museum representations of human evolution: The unquestioned and the challenged in learners’ meaning making. Science & Education, 0123456789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-021-00314-y

Plummer, J. D., Tanis Ozcelik, A., & Crowl, M. M. (2021). Informal science educators engaging preschool-age audiences in science practices. International Journal of Science Education, Part B: Communication and Public Engagement, 11(2), 91–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/21548455.2021.1898693

Pshenichny-Mamo, A., & Tsybulsky, D. (2023). Natural history museum guides’ conceptions on the integration of the nature of science. Science & Education, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-023-00469-w

Shaby, N., Assaraf Ben-Zvi, O., & Tal, T. (2019a). An examination of the interactions between museum educators and students on a school visit to science museum. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 56(2), 211–239. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21476

Shaby, N., Assaraf Ben-Zvi, O., & Tal, T. (2019b). Engagement in a science museum – The role of social interactions. Visitor Studies, 22(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10645578.2019.1591855

Tal, T., & Morag, O. (2007). School visits to natural history museums: Teaching or enriching? Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 44(5), 747–769. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20184

Tran, L. U. (2007). Teaching science in museums: The pedagogy and goals of museum educators. Science Education, 91(2), 278–297.

Tran, L. U., & King, H. (2007). The professionalization of museum educators: The case in science museums. Museum Management and Curatorship, 22(2), 131–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647770701470328

Tran, L. U., & King, H. (2011). Teaching science in informal environments: Pedagogical knowledge for informal educators. In D. Corrigan, J. Dillon, & R. Gunstone (Eds.), The professional knowledge base of science teaching (pp. 279–293). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-3927-9

Tsybulskaya, D., & Camhi, J. (2009). Accessing and incorporating visitors’ entrance narratives in guided museum tours. Curator, 51(1), 81–100.

Tsybulsky, D. (2019). Students meet authentic science: the valence and foci of experiences reported by high-school biology students regarding their participation in a science outreach programme. International Journal of Science Education, 41(5), 567–585. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2019.1570380

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Pshenichny-Mamo, A., Tsybulsky, D. (2024). Museum Guides’ Views on the Integration of the Nature of Science While Addressing Visitors’ Experiences: The Context of Ecological and Evolutionary Issues. In: Korfiatis, K., Grace, M., Hammann, M. (eds) Shaping the Future of Biological Education Research . Contributions from Biology Education Research. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-44792-1_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-44792-1_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-44791-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-44792-1

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)