Abstract

This chapter introduces Coleman and Putnam’s social capital theory and discusses its potential for inspiring reflection on the social practice of ECEC’s collaboration with children’s families. Specifically, the theory promotes reflection on the relationships that develop through a new community of parents and professionals coming together, as well as the new interconnectedness among the parents, which extends the social capital of a particular family and becomes a profitable investment in the child’s future. Understanding the concept of social capital allows for the identification of which forms are being blocked, as well as the bridging and bonding that are not occurring. The empirical case presented in this chapter highlights the role of ECEC’s recognition of a family’s culture as a bridge to the parental community. The chapter concludes with a discussion of ECEC’s role in strengthening the family’s network in times where intense migration, mobility, and other factors may impede its growth.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Different Understandings of Social Capital

In the preceding chapter, Bourdieu’s social theory, specifically his understanding of social capital, was presented. In this chapter, I discuss Coleman’s understanding of social capital and show how it is related to the social practice of parental involvement in ECEC.

As quoted in Chap. 8, Bourdieu defined social capital as “the aggregate of the actual or potential resources which are linked to possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalised relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition – or in other words, to membership in a group – which provides each of its members with the backing of the collectively owned capital” (Bourdieu, 2004, p. 21). However, in Bourdieu’s work, membership and access to certain profitable networks are connected to a particular social positioning and thus power relations. This is to say that Bourdieu’s focus is on how social capital depends on economic and cultural capital, and how it reproduces the capitals. Coleman (1998), however, focuses more on the profits of social capital and less on the social positioning or inclusive/exclusive character of diverse memberships. Accordingly, he highlights the function of social capital and relates it to the notion of a common profit or the common good (rather than to the perpetuation of social inequalities).

As Coleman wrote,

Social capital is defined by its function. It is not a single entity but a variety of different entities, with two elements in common: they all consist of some aspect of social structures, and they facilitate certain actions of actors – whether persons or corporate actors – within the structure. Like other forms of capital, social capital is productive, making possible the achievement of certain ends that, in this absence, would not be possible. (Coleman, 1998, p. 98)

What this shows is that Coleman understood social capital as permanently inherent in relationships between individual and collective social actors, and as facilitating a profitable action. However, “a given form of social capital that is valuable in facilitating certain actions may be useless or even harmful for others” (Coleman, 1998, p. 98). In other words, a particular quality of relationships between people becomes social capital only if it is based on a joint benefit, one that none of the participating actors would be able to achieve on its own.

Social Capital as Inherent in Relations

Social capital “exists in the relations among persons” (Coleman, 1998, pp. 100–101, emphasis original). As “human capital is created by changes in persons that bring about skills and capabilities that make them able to act in new ways,” social capital “comes through changes in the relations among persons that facilitate action” (Coleman, 1998, p. 100). In acknowledging the importance of how people come together (to create beneficial actions), Coleman reflected on the diverse social structures that strengthen social capital. He described the benefits of structures with closure, by which he meant a “closed” social structure within a clearly limited number of members who respect the common norms and trust that the other members do as well:

If A does something for B and trusts B to reciprocate in the future, this establishes an expectation in A and an obligation on the part of B. (Coleman, 1998, p. 102)

Norms, expectations, and trustworthiness are, according to Coleman, characterising structures with strong social capital. The norms of living in a community that are established through expectations and trust in each other are the factors that safeguard the community’s capacity for joint action. When discussing these norms, mutual trust, and expectations, Coleman did not appear to perceive the significance of class, gender, ethnicity, sexuality, and ability-related differences, which, according to his critics, shows his theory to be in silent agreement with and thus reproducing established power, loyalty, and discriminatory relations (Edwards et al., 2003, pp. 9–11).

In the process of using social capital theory to reflect on the practice of parental involvement, I will take the risk of stating that Coleman’s blindness of class, gender, ethnicity, sexuality, and ability may work as an advantage. The advantage consists of the possibility of focusing on parental collaboration, as ECEC professionals are supposed to do, regardless of any differences. Focusing on social capital allows us to focus on relations between parents and the ECEC, children and parents, and parents and other parents; it also allows us to reflect on the potential implied in these relations for everyone, regardless of the diversity in social positioning and power relations.

Nevertheless, when some relations do not show their capital or work in a beneficial way for the actors involved, the question of the relevance of power, gender, social class, and ethnicity becomes absolutely essential.

(Parents) Bridging and Bonding: Putnam’s Perspective

Putnam, another theoretician of social capital, acknowledged the categories of difference (e.g., social class, gender, ethnicity, and disability), but not as posing limits on social capital. Rather, he saw differences as enabling a variety of forms of social capital. He distinguishes between bridging and bonding types of social capital, whereby bridging expands networks by enabling relations across social differences, while bonding strengthens cohesion between established and rather homogeneous groups (Putnam, 2000).

Regardless of whether the type is bridging or bonding, social capital functions as a “universal lubricant” of social relations (Putnam, 2000). In relation to parental involvement and collaboration with an ECEC centre, bridging and/or bonding may draw different constellations among parents, as well as between parents and professionals. Hurley (2017) relates bridging to overcoming the power imbalance between ECEC professionals and parents, and bonding to the process of strengthening ties among parents. However, in considering diversity among parents in terms of social class, ethnicity, gender and sexuality, religion, and (dis)ability, the bridging form of capital may also be relevant. Being parents of children in the same ECEC settings may activate bridging connections between social groups that otherwise would never interact. Nevertheless, being parents of children in the same ECEC does not necessarily cancel all the differences and inequalities among parents and allows them to easily “bridge” to each other. Regardless, being put together in a community of parents may also provoke and strengthen bonding within distinctive parental groups, including those of higher and lower social classes, as well as those with education-related and non-education-related connections. Moreover, parents who are teachers may show a tendency to bond more with teachers than other parents. Bridging and bonding may look differently in each context, as the categories of parents and ECEC professionals are not the only categories of difference that require the “lubricant” of social relations.

Social Capital as a Resource or Ability of the Network

Regardless of the many different ways of enabling social capital, it remains unclear what social capital itself really is. The criticisms of Coleman’s conception of social capital relate to the unclarity of the distinction between the resources and the abilities of the network members. At the moment when individual resources become a group’s ability for action, social capital “becomes conceptually fuzzy” (Tzanakis, 2013, p. 5). What may be confusing in Putnam’s work is that social capital sometimes relates to networks themselves, and sometimes to their effects, and it is unclear whether the networks themselves are enough to be considered as social capital. Bizzi (2015), however, states that social capital and social networks are two independent but related terms, pointing out that social networks are the basis for social capital, as the latter is enabled by the resources provided by the social networks.

When relating social capital to parental involvement in ECEC, this confusion between resources and abilities does not seem to matter. From the perspective of ECEC’s collaboration with parents, the most important concern is that diverse resources and abilities of all parents can be activated in parental relations with the ECEC and relations among parents, and parental relations with (not only one’s own) children. Moreover, enabling new relations and connections of these kinds is seen as value and as capital.

Social Capital as Investment

Bourdieu (1985), Coleman (1998), and Putnam (2000) all underline the beneficial or potentially beneficial character of social capital. The existing or future benefits of certain relations allow us to look at social capital as an investment and a resource with its own economics. Bankston’s (2022) description of social relationships as investments that afford access to diverse kinds of goods (that without these relationships are inaccessible) is an example of social capital as investment.

Investing in social capital can be recognised as essential for vulnerable families whose social ties are limited to the underprivileged community, which again affects their children. When lacking cultural and economic capital, it seems rational to invest in social relationships that may afford access to better jobs and thus economic resources through which one can gain access to diverse cultural goods and experiences. However, following Bourdieu (1985), membership in particular networks already requires particular levels of cultural and or economic capital right at the start. Coleman (1998) identified the importance of norms and trustworthiness in enabling social capital, access to which depends on knowledge about the norms and the capabilities of obeying them (i.e., a particular type of cultural capital). In Bankston’s (2022) view, cultural capital is only one of the dimensions of social capital that is recognised in the norms and values of a society/community/network.

Putnam (2000), however, claims that cultural capital can grow on the basis of networks and their capital. In other words, it is networking that leads to the sharing of knowledge, experiences, and support, and it is not knowledge, experience, and the ability to support that is at stake before entering a network. According to Putnam (2000), it is trust that comes first. Trust enables horizontal linking between people and their civic engagement, which may develop into grassroots organisations following the redistribution of other resources. Putnam associates trust with civic engagement and Coleman with the common good. However, the benefits of social capital and redistributed resources do not always function for the good of society or democracy, as there are networks with practices that openly conflict with social welfare, such as those affiliated with corruption or mafia groups that exemplify strong social capital.

Social Capital in/of/Through Parental Involvement

Adler and Kwon (2002) have shown that educational institutions, by connecting families with each other and a larger community than themselves, contribute to the creation of social capital. ECEC’s collaboration and partnership with parents and caregivers is a relationship that comprises the resources and abilities of all involved, and that may be beneficial for both the more vulnerable and the better-situated families, as well as all the children. However, depending on the ECEC tradition in a particular country/culture/context, the goal of “joining forces” may be different. The desired effect of relationships between one’s home and the ECEC will be different in cultures/countries/contexts that practice pre-school traditions, as opposed to others where the social pedagogy tradition dominates (Bennet, 2010). While in the former tradition, the school readiness of each child will be at stake, in the latter, the focus will be directed toward the community’s efforts to safeguard all children’s well-being in their relationships with each other and the community.

Parent-Teacher Partnerships as Social Capital

Connecting parents and teachers creates a new community within which there are mutual obligations, expectations, different types of communication, and rules. On the one hand, the norms are inspired by the steering documents (e.g., curricula, framework plans, etc.). On the other hand, the norms may be influenced by those of the other communities in which the parents participate.

This means that an ECEC parents’ community is a community joining people whose daily family and professional lives take place in different social circles, each of which may have distinctive norms. It is thus likely that the norms and rules of the other social circles of parents and professionals will affect the relationship between parents and teachers. In other words, different parents could have different perspectives on the child, different values and beliefs about the child’s upbringing, and different ways of interacting with others. Parcel and Bixby (2016) emphasise the social capital contained in the connections of different values and norms of heterogeneous communities emerging at educational institutions. However, they also underline the importance of teachers understanding the different ways of raising children and remaining able to react if they observe any abuse of formal regulations of care and upbringing.

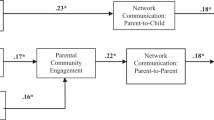

The social circles and networks coming together in the new community of parents and professionals in an ECEC setting are related to the social capital index developed by Onyx and Bullen (2000). The factors of this social capital index are emphasised with italics in the text below. Both parents and teachers are participating in a local community within and possibly also outside of the ECEC settings. By engaging in or organising various activities, they show certain levels of agency. Connections and relationships between the ECEC and the parents and among the parents are (ideally) founded in feelings of trust and safety, and in case these feelings are not there yet, it is the ECEC’s role to gain the parents’ trust and ensure their safety. It is possible that bonding between parents forms informal neighbourhood connections and friends’ connections. It is also possible that good neighbours may become members of the parental community in the same ECEC setting. As families and professionals may have different values and norms, respect and appreciation of diversity are prerequisites for establishing mutual relationships. Finally, both parents and teachers should feel valued by the newly established community. All these social capital indicators, which it may be possible to detect in parents collaborating with/through an ECEC setting, show the interconnectedness of both parents and teachers that enhances social capital and further enriches communities (Purola & Kuusisto, 2021).

Parental Involvement: Strengthening the Family’s Social Capital

For many families, early childhood and pre-school education institutions are their first step into a new institutional world and its communities. Entering the new social/institutional arenas may confirm their already-acquired norms of interaction, but it may also demand adjustments and adaptations to the norms of the newly formed community. In Putnam’s (2000) view, becoming parents of children attending the same ECEC creates a level of trust that enables new connections and interactions of a bridging and bonding character that truly enrich the social capital of the families involved.

In modern society, with the dominant model of nuclear families, children’s social networks are increasingly narrow. A decrease in the number of family members, together with a weaker connection with the older generations due to separation because of migration or economic factors, significantly limit the networks in which children live and become (Ribbens McCarthy & Edwards, 2011). Moreover, this phenomenon sheds light on the critical aspects of care-taking, upbringing, and socialisation in the nuclear family. In such a situation, the child’s participation in an ECEC becomes the entire family’s link to new connections, new relations, and a supportive network. Particularly, parents in analogical situations may easily become the new “extended family”; however, such support may also come from the teachers/ECEC staff.

The families extending their networks through the child’s participation in ECEC can be described in terms of bridging, which entails extending their own social relations (Putnam, 2000), or in terms of a fusion of social networks (Coleman, 1998). Coleman describes the social network of children and their parents as predictable in educational institutions. The children within an ECEC institution create relations with other children, previously unknown, while remaining in relations with their own parents, who have also had the opportunity to interact in/through the educational institutions. Such an inevitable model of relations, limited to a particular member of a community (ECEC or school), is what Coleman calls a social structure “with closure” (Coleman, 1998). Such “closed” kinds of networks create a possibility for developing norms, which again strengthen the expectations, trustworthiness, and thus social capital. In the case of such a network of parents and children knowing each other, the parents have an opportunity to communicate about the norms of their children’s interactions, behaviour, and activities. For example, they may discuss how much screen/gaming time would be allowed during one child’s visit to the other. Such a norm will impose expectations towards each other and thus trustworthiness, as well as social control (Tzanakis, 2013).

Social Capital or Disturbing Interference?

Coleman (1998) states that one’s engagement in social interactions, relationships, and networks lasts as long as all involved profit from these relations. In the case of parental involvement, one might ask how the parents and ECEC perceive the benefits of belonging to networks enabled by the ECEC setting.

Some countries/communities/cultural contexts do not recognise the benefits of the teachers’ and families’ influences on each other and impose strictly separate roles of professionals responsible for education and parents responsible for upbringing. The approach of non-interference may, however, relate to only one of the parts, such as a professional’s attitude of non-interference in family functioning, or the family’s attitude of non-interference in professional functioning (Blândul, 2012; Kultti & Pramling-Samuelsson, 2016).

Prior and Gerard (2007) give an example of cooperation being practised in the form of communicating educational intentions, while the parental say at school may be seen as an interference or disturbance. Such cooperation might be seen by the parents as beneficial in terms of allowing access to the (pre)school’s perspective and intentions, but they may feel unrecognised as the first educators of their children, as in such a case, they may be seen as representing insufficient knowledge and skills.

Apart from the views on (non)interference, there is a great diversity of options for how cooperation should be practised in accordance with different policies. While educational policies may emphasise the importance of cooperation between families and (pre)schools, it is the autonomy of the (pre)school that becomes a key factor in how the relationship with the families is established and maintained (Granata et al., 2016) and what opportunities for networking the parents are exposed to. An interesting example of different implementations of the same policies comes from Norway. The Norwegian Framework Plan for Kindergarten (UDIR, 2017) states that “the kindergarten must seek to prevent the child from experiencing conflicts of loyalty between home and kindergarten” (p. 29). Two parents whom I contacted through a research project with the co-author of this book told me about their experiences with ECECs introducing the no-cake and no-sugar rule for birthday celebrations. As the Framework Plan obligates them to introduce the children to healthy lifestyles and good nutrition, they thought that birthday celebrations needed to change. However, the ECECs chose very different ways of involving the parents in the process.

The first parent talked about the ECEC organising an extraordinary parental meeting, where the ECEC staff presented the number of cakes being eaten every month/year and the excessive sugar intake this had caused. The ECEC invited the parents to participate in a discussion on healthier ways of marking and celebrating birthdays. Parental discussions helped generate different ideas, which all the parents voted for/against. In such a way, “a fruit plate and group dance” became the kindergarten’s way of celebrating birthdays. When summing up the parental work, the headmaster asked the parents to communicate the result of the parental meeting to the children, so that they knew that all of the parents were involved in the co-creation of a “happy/healthy birthday to you” project.

The second parent told us about receiving a letter informing us that “no one will be allowed to bring birthday cakes for birthday celebrations of the child, as the kindergarten has implemented a no-sugar policy.” The decision was justified by a relevant quote from the Framework Plan and a discussion with one parental representative. At the end of the letter, the parents were left with the following: “Please do not talk negatively about our decision to your child, as it may develop a loyalty conflict between the child’s home and the kindergarten” (Letter, Parent 2).

These two stories illustrate how differently the same policies of the Framework Plan (promoting healthy nutrition and preventing loyalty conflicts) were implemented in different institutional settings of an ECEC. The first implementation allowed for active parental participation in developing ideas, and the second put the parents in the role of passive receivers of the ECEC’s decisions, with an additional ban of any criticism. It is questionable whether the “collaboration” as presented in the second case may generate any form of social capital. If so, this would only emerge in the form of parents bonding together against the kindergarten’s decision.

Democracy Deficit

Seeing parental influence as an interference or disturbance may be related to the democracy deficit described by Van Laere et al. (2018), where “the goals and modalities of parental involvement are defined without the involvement of parents themselves” (p. 189). When relating this democracy deficit to the social capital concept, Keyes’s (2002) work discussing the goals for ECEC collaboration with parents is especially enlightening. Social capital activates groups to work together to achieve a common aim or good (Coleman, 1998). However, in terms of ECEC’s collaboration with parents, the aim is not necessarily a result of communication between the ECEC and families, but rather decided in advance of parents entering the institution. The imposed aim forces the norms and expectations onto the parents and shows only those who fit and identify with the aim to be trustworthy. Even though many middle-class parents fit the expectations and comply with the imposed goal, many families of other backgrounds remain unrecognised as valuable resources for the child, the ECEC, and other parents.

Social Capital Enabled by Recognising Family Culture as a Resource

The diversity of modern societies is reflected in the diversity of the cultural identities of children and families attending ECECs, and this allows us to understand ECEC settings as arenas for social inclusion (Sadownik, 2020; Višnjić-Jevtić et al., 2021) and thus social sustainability (Sadownik et al., 2022; Višnjić Jevtić & Visković, 2020). The inclusion emerges ideally through bridging the children and families who, without the ECEC setting, would never meet each other and have an opportunity to bond. In the bridging-bonding relation between the ECEC and a family, it is also important to establish joint understanding and continuity of educational activities and values (Višnjić-Jevtić, 2021). This requires that the family is seen as an important resource in the child’s life, and also as the ECEC’s social capital in allowing the professionals to access other knowledge and perspectives on the child. Being seen as social capital, parents gain a new role—the role of respected partners in education—which affects both their confidence and competence as parents (Shartrand et al., 1997; De Bruïne et al., 2014). Their personal experience “bridges” (Hurley, 2017) their family to the ECEC institutions, where it becomes a resource that bonds the ECEC and the parents.

However, as mentioned earlier in this chapter, the family’s capital may not always bridge into ECEC contexts, and not all parents must necessarily bond together. The bridging and bonding may relate to only some of the parents and exclude others. In the case study below, I illustrate such an inclusive/exclusive work of bridging and bonding in the context of Croatia.

Empirical Case

Croatia is a country where the majority of the population is Croats (91.63%); the rest of the population consists of nationalities represented in much smaller numbers. Serbs make up 3.20% of the population, Bosnians 0.60%, and Roma 0.46%, while others are represented by less than 0.40% (CBS, 2022). Although a total of 22 national minorities live in Croatia, they are often not recognised or highlighted in ECEC settings. An exception is the case of ECEC settings that work in the language and script of national minorities (e.g., ECEC for Hungarian, Czech, or Italian national minorities following the educational policies of each respective country). However, what often happens is that there is a strong recognition and celebration of families coming from very distant cultures and countries. These cultures seem to be recognised and acknowledged as potentially valuable and resourceful co-creators of the ECEC’s pedagogical offerings. The story of Arthur, described below, exemplifies this kind of unequal distribution of appreciation and ignorance of the family’s background.

Arthur is 5 years old. He comes from a multicultural environment (i.e., his mother and father come from different continents and are of different ethnicities and native languages) and is enrolled in an ECEC setting in Croatia. The ECEC does not speak any of the languages in which the family communicates, which is why communication with the parents takes place in English. In fact, communication with the child takes place in a combination of Croatian and English. The teachers make an extra effort to ensure that the whole family feels welcome, so they adjust the communication forms to the family’s needs. The boy quickly learns the Croatian language. Despite the initial difficulties in communicating, the boy has been included by the peer group and invited to play since day one. As time passes, the children start becoming curious about the languages Arthur’s parents speak and the countries they come from.

Seeing that the children’s group is interested in knowing more about Arthur’s family’s culture, the teachers encourage more intensive cooperation with Arthur’s parents, especially his mother. The mother is open to spending one whole day in the ECEC setting. That day is a holy day of celebration in the country that she is from. The celebration requires some preparation of materials and activities, with which the teachers actively help. The day is a great success, with all the children and teachers getting involved in new activities. Arthur feels that his home culture is recognised and respected by the ECEC, which leads to further involvement of the mother in organising more activities connected to songs, games, traditional food, spices, and customs connected to birthday celebrations.

The positive effects of these intercultural activities are communicated to other parents. During parental meetings, the teachers create groups so that Arthur’s parents can join others who can and want to communicate in English, and this allows Arthur’s parents to feel included. The parents express appreciation for the intercultural resources that are made accessible for their children during the days when Arthur’s mother became involved in the ECEC. After 4 months, Arthur’s parents become a “natural” part of the parental community and are increasingly connected with other families. The families of other children become their extended family. They help each other with picking up the children, “baby-sitting,” and other things that a family with children may need.

The ECEC staff is aware that such smooth inclusion happened thanks to their first efforts in making the bridging possible. Creating an environment of joint understanding where Arthur’s family was perceived as a great resource for the ECEC, and by adjusting the communication forms and languages so that their active participation was possible, the ECEC overcame the obstacles that potentially could have stopped the bridging. Providing arenas in which all the parents and children could get to know Arthur and his multicultural home environment gave all the families an opportunity for bonding, which was extended through the help they continued to provide for each other.

What is interesting in this case is the reason the teachers decided to provide Arthur’s family with support during the bridging and bonding with the parental community. In my view, the teachers had a genuine recognition of the family’s cultural capital as a resource for Arthur, the other children, and the entire ECEC community. This may seem surprising, particularly if one knows that this ECEC is attended by other children of minority backgrounds whose cultural capital is not recognised as a resource and whose culture is not accounted for in the pedagogical content, and the parents are left alone in paving their way to inclusion in the parental community. For some reason, Arthur’s multicultural background was attractive enough to be celebrated, while the others were not. This therefore raises the question of which powers decide on the kind of family culture that should be recognised as a resource and thus enable social capital, and which families are denied such recognition and thus must struggle with bridging into the parental community. Is it the “attractiveness” of the culture that is chosen to be celebrated? Are there personal rather than professional values steering such decisions, or is it perhaps the effect of wider social processes, such as the assimilation of some groups? As the ECEC setting is a part of a wider society and its traditions, one of which may be connected to the long-term assimilation of particular minorities, the promotion of some cultural backgrounds may thus be unthinkable and unimaginable for the ECEC staff.

Conclusion

In this chapter, I presented the theorisations of social capital developed by Coleman and Putnam as possible ways of reflecting on ECEC’s collaboration with diverse parents and families. By discussing the different ways of interpreting the value of extending a family’s network, this theoretical toolkit also allows us to reflect on the grouping and bonding that may have an exclusionary or negative effect. The main conclusion of this chapter, supported by the empirical case, is that it is in the ECEC’s power to enable different parents’ bridging into the parental community, and thus facilitate stronger bonding with particular families. In times of migration, mobility, and diversity, in which many families may lack good, supportive networks, the conscious work of how an ECEC to interconnect these families is of great importance.

References

Adler, P. S., & Kwon, S. W. (2002). Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Academy of Management Review, 27(1), 17–40.

Bankston, C. (2022). Rethinking social capital. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Bennet, J. (2010). Pedagogy in early childhood services with special reference to Nordic approaches. Psychological Science and Education, 15(3), 16–21.

Bizzi, L. (2015). Social capital in organizations. In J. D. Wright (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (pp. 181–185). Elsevier.

Blândul, V. C. (2012). The partnership between school and family-cooperation or conflict? Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 47, 1501–1505.

Bourdieu, P. (1985). The forms of capital. In J. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). Greenwood.

Bourdieu, P. (2004). The peasant and his body. Ethnography, 5(4), 579–599.

Coleman, J. S. (1998). Social capital in the creation of human capital. The American Journal of Sociology, 94, 95–120.

Croatian Bureau of Statistics (CBS). (2022). Popise stanovništva, kućanstava i stanova 2021. CBS.

De Bruïne, E. J., Willemse, T. M., D’Haem, J., Griswold, P., Vloeberghs, L., & van Eynde, S. (2014). Preparing teacher candidates for family–school partnerships. European Journal of Teacher Education, 37(4), 409–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2014.912628

Edwards, R., Franklin, J., & Holland, J. (2003). Families and social capital: Exploring the issues (p. 1). South Bank University.

Granata, A., Mejri, O., & Rizzi, F. (2016). Family-school relationship in the Italian infant schools: Not only a matter of cultural diversity. Springer Plus, 5, 1874. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-3581-7

Hurley, R. (2017). Bonding & bridging social capital in family & school relationships (Doctoral dissertation). University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

Keyes, C. R. (2002). A way of thinking about parent/teacher partnerships for teachers. International Journal of Early Years Education, 10(3), 177–191.

Kultti, A., & Pramling-Samuelsson, I. (2016). Investing in home–preschool collaboration for understanding social worlds of multilingual children. Journal of Early Childhood Education Research, 5(1), 69–91.

Onyx, J., & Bullen, P. (2000). Measuring social capital in five communities. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 36(1), 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886300361002

Parcel, T. L., & Bixby, M. S. (2016). The ties that bind: Social capital, families, and children’s well-being. Child Development Perspectives, 10(2), 87–92.

Prior, J., & Gerard, M. R. (2007). Family involvement in early childhood education: Research into practice. .

Purola, K., & Kuusisto, A. (2021). Parental participation and connectedness through family social capital theory in the early childhood education community. Cogent education, 8(1), 1923361.

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon & Schuster.

Ribbens McCarthy, J., & Edwards, R. (2011). Key concepts in family studies. Sage.

Sadownik, A. R. (2020). Insights from research: “Translating” the kindergarten to international parents. In L. Hryniewicz & P. Luff (Eds.), Partnerships with parents in early childhood education settings (pp. 92–101). Routledge.

Sadownik, A., Phillipson, S., Harju-Luukkainen, H., & Garvis, S. (2022). International trends in parent involvement of sayings, doings, and relatings. In S. Garvis, S. Phillipson, H. Harju-Liuukkainen, & A. R. Sadownik (Eds.), Parental engagement and early childhood education around the world. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203730553

Shartrand, A. M., Weiss, H. B., Kreider, H. M., & Lopez, M. E. (1997). New skills for new schools: Preparing teachers in family involvement. Harvard Family Research Project, Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Tzanakis, M. (2013). Social capital in Bourdieu’s, Coleman’s and Putnam’s theory: Empirical evidence and emergent measurement issues. Educate~, 13(2), 2–23.

UDIR. (2017). Framework plan for kindergartens. Content and tasks. https://www.udir.no/globalassets/filer/barnehage/rammeplan/framework-plan-for-kindergartens2-2017.pdf

Van Laere, K., Van Houtte, M., & Vandenbroeck, M. (2018). Would it really matter? The democratic and caring deficit in ‘parental involvement’. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 26(2), 187–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2018.1441999

Višnjić-Jevtić, A. (2021). Parents’ perspective on a children’s learning. Journal of Childhood, Education & Society, 2(2), 117–125. https://doi.org/10.37291/2717638X.20212266

Višnjić Jevtić, A., & Visković, I. (2020). Insights from research: Collaborative competences of kindergarten teachers. In L. Hryniewicz, P. Luff (Eds.), Partnership with parents in early childhood settings: Insights from five European countries (pp. 55–66). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429437113-9

Višnjić-Jevtić, A., Sadownik, A. R., & Engdahl, I. (2021). Broadening the rights of children in the Anthropocene. In A. Višnjić-Jevtić, A. R. Sadownik, & I. Engdahl (Eds.), Young children in the world – And their rights: Thirty years with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (pp. 237–273). Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Višnjić Jevtić, A. (2023). Together, We Can Do More for Our Children . In: Sadownik, A.R., Višnjić Jevtić, A. (eds) (Re)theorising More-than-parental Involvement in Early Childhood Education and Care. International Perspectives on Early Childhood Education and Development, vol 40. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-38762-3_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-38762-3_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-38761-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-38762-3

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)