Abstract

Rangelands are vast, dynamic, and integral to providing habitat for thousands of vertebrate and invertebrate species, while concurrently serving as the foundation of human food and fiber production in western North America. Reciprocally, wildlife species provide critical services that maintain functional rangeland ecosystems. Therefore, human management of rangelands via fire, grazing, agricultural programs, and policy can enhance, disturb, or inhibit the necessary interactions among natural processes of plants and animals that maintain rangeland ecosystems. As conservation issues involving rangelands have grown in societal awareness and complexity, rangeland managers, wildlife biologists, and others have discovered the need to work more closely together with an increasingly holistic approach, spurring a rapid accumulation of rangeland wildlife information in the early twenty-first century. This book represents a synthesis of contemporary knowledge on rangeland wildlife conservation and ecology. Accordingly, we provide a review of the state of science for new, as well as seasoned, wildlife and rangeland professionals who have stewardship of North America’s most undervalued ecosystem.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1.1 Introduction

More than half of all lands worldwide, and the majority of lands in the western U.S., are classified as rangelands (Table 1.1). The exact extent of rangelands is difficult to delineate due to variability in the definition of rangelands (Briske 2017), but by any definition rangelands represent collectively the most widespread ecosystem in the western U.S. (Chap. 2). Many picture grasslands when envisioning rangelands. Some classify rangelands as any non-cultivated land grazed by livestock (Menke and Bradford 1992). Others have defined rangelands as ‘non-forested lands of low economic activity’ (sensu Sayre 2017). In most cases, rangelands in North America represent what was ‘left over’ after Euro-American settlement and conversion of arable lands in the West during the nineteenth century (Table 1.1). Therefore, rangelands include desert, grassland, and shrubland ecosystems that were unsuitable for cultivation, though they retain economic and social value. Rangelands are held in public or private ownership and provide innumerable goods and services, including significant economic benefit to local communities. For example, nearly 100 million head of cattle spend at least part of their life each year on U.S. rangelands alone. Rangelands also provide habitat for hundreds of vertebrate species and innumerable invertebrates. Thus, rangelands and their management have significant bearing on wildlife in North America and globally.

Wildlife have been a featured player in the history of rangelands (Chap. 3) but are more than that—they are a fundamental piece of the whole that constitute rangeland ecosystems. Wildlife and rangeland management as scientific disciplines share common origins and parallel histories (Chap. 30). Foundations of each were based upon concepts developed in the pioneering field of forestry and focused on sustainable harvest of products—timber, forage, deer, quail. Each field has seen similar progressions in ideas expanding from sustainable harvests of ‘valuable’ species to adaptive management of functional and resilient ecosystems. This broadening of focus has, no doubt, reflected shifting demographics and stakeholders (van Heezik and Seddon 2005), that have pushed ecologists and managers to think more holistically about rangeland ecosystems as more than the sum of their offtake. Contemporary managers must not only know theories describing population responses of harvest management—either by cow or gun—but should have broader knowledge that includes invasive species ecologies as related to state transitions, policy issues related to threatened and endangered species, functional vs. biological diversity, and so much more. This broadening means that contemporary rangeland and wildlife managers should have training in landscape ecology, community ecology, and rangeland and wildlife policy, in addition to foundational understandings of the biology and ecology of plants and animals. Now layer onto those scientific concepts the fact that rangelands are almost always working lands inextricably linked to a people’s sense of place and identity (Chap. 28), and the knowledge required to understand rangeland ecosystems, including rangeland-dependent wildlife, becomes broad and transdisciplinary.

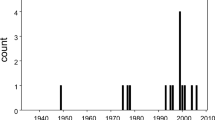

That wildlife are integral parts, not just benefactors, of rangeland ecosystems has been understood by native peoples in North America for thousands of years, but not until the late-twentieth century did scientists begin investigating their interactions. In 1996, the Society for Range Management published a volume summarizing information about select vertebrates that inhabited western United States rangelands (Krausman 1996). Although Krausman (1996) still serves as a well-worn reference for rangeland and wildlife managers, a wealth of new information concerning rangeland wildlife has been produced since its publication. For example, a Web of Science search for “rangeland wildlife” produced 790 peer-reviewed publications during 1996–2019 (date of search 10/15/19); by comparison, less than 50 publications were found for the period 1900–1995. As conservation issues have become increasingly more common during this modern Anthropocene, some of the highest profile cases have been with rangeland-dependent wildlife. We are now well past a time when rangeland and wildlife disciplines can remain siloed within their educational and professional pursuits. Our goal for Rangeland Wildlife Ecology and Conservation has been to corral the best available science during the last quarter century that addresses rangeland wildlife ecology, conservation, and management into a product that will serve and help integrate professionals of the rangeland and wildlife disciplines.

1.2 What This Book Is

By necessity, if not by design, Rangeland Wildlife Ecology and Conservation is a hybrid. Textbooks are traditionally written cover to cover by the same author(s) and attempt to distill major ideas in a discipline to something learnable in a semester; whereas edited volumes in a book series are an assemblage of separate and sometimes disparate articles—often documenting a conference symposium—that synthesize the state of knowledge on a topic. In our hubris to achieve both, we recruited more than 100 subject matter experts to author 30 chapters on topics we identified as needing an updated review—the authors list includes university and federal scientists, state and federal rangeland and wildlife managers, NGO scientists and conservationists, and ranchers. The result of this 3-year effort is both a synthesis of knowledge on major rangeland wildlife topics and a contemporary (2022 c.e.) review of the state of the science that we hope can be used as both a modern textbook in the training of students in rangeland and wildlife science as well as a reference for working professionals.

1.3 What This Book Is Not

Certainly, the Rangeland Wildlife Ecology and Conservation is not a full and exhaustive summary of everything rangeland managers and wildlife biologists should know. For example, we acknowledge that soil properties and processes are critical drivers of rangeland ecosystems with important implications for wildlife habitat management; fortunately, a recent excellent review is provided elsewhere (Evans et al. 2017). We have asked our authors to incorporate discussions of management tools (e.g., fire, grazing, conservation programs and policy) into their chapters where appropriate, but this book is not a paint-by-numbers recipe for the management of wildlife on rangelands. That is impossible. Recent work, as demonstrated throughout this book, has highlighted (1) what is unknown and uncertain, and (2) that wildlife interactions and responses to rangeland management are context- and scale-dependent. Proper rangeland management to achieve habitat targets for even a single species in a single rangeland type will vary across space and time due to differences in soils, topology, and precipitation. Instead, we asked authors to synthesize information relative to habitat targets and describe how those may be influenced by managed (e.g., grazing) and unmanaged (e.g., precipitation) conditions so that the content may be principle based and applicable across the distribution of a species. Local expertise is always needed for proper management.

1.4 Organization

Rangeland Wildlife Ecology and Conservation is divided into three parts. In Part I (Chaps. 2–8), rangeland scientists introduce the reader to major concepts in rangeland ecology and management in western North America. Part I is not meant to be an exhaustive review of the ecology and management of rangeland ecosystems; there are excellent texts that do that (e.g., Briske 2017), but we felt that inclusion of this introductory material would be beneficial for wildlife professionals who may not have had previous training in rangeland ecology. Part II (Chaps. 9–26) includes accounts in which subject matter experts present updated reviews and syntheses of representative and well-studied species or guilds thereof. To aid in the use of this book as a text and reference, the chapters in Part II share a common structure and include (1) introductory sections on species life-histories, population dynamics, and habitat requirements, (2) current methods for effective population monitoring, (3) syntheses describing interactions with rangeland management, including livestock grazing and fire, and (4) a summary of current threats to ecosystems. Because rangelands are almost always working landscapes (Table 1.1), we conclude the book in Part III with chapters demonstrating the importance of social-ecological understanding of rangelands, that land, livestock, and wildlife management are intertwined, and how that knowledge can be leveraged into more effective and holistic conservation of rangeland wildlife.

References

Briske DD (2017) Rangeland systems: processes, management, and challenges. Springer Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-46709-2

Charnley S, Sheridan TE, Sayre N (2014) Status and trends of western working landscapes. In: Charnley S, Sheridan TE, Nabhan G (eds) Stitching the West back together. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 13–32. https://doi.org/10.7208/9780226165851

Evans RD, Gill RA, Eviner VT, Bailey V (2017) Soil and belowground processes. In: Briske DD (eds) Rangeland systems: processes, management, and challenges. Springer Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-46709-2_4

Hruska T, Huntsinger L, Brunson M, Li W, Marshall N, Oviedo JL, Whitcomb H (2017) Rangelands as social-ecological systems. In: Briske DD (eds) Rangeland systems: processes, management, and challenges. Springer Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-46709-2_8

Krausman PR (1996) Rangeland wildlife. Society for Range Management, Denver, CO. https://srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/62529

Menke J, Bradford GE (1992) Rangelands. Agr Ecosyst Environ 42:141–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-8809(92)90024-6

Sayre NF (2017) The politics of scale: a history of rangeland science. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

van Heezik Y, Seddon P (2005) Structure and content of graduate wildlife management and conservation biology programs: an international perspective. Cons Biol 19:7–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.01876.x

Walker B (2010) Riding the rangelands piggyback: a resilience approach to conservation. In: du Toit JT, Kock R, Deutsch JC (eds) Wild rangelands: conserving wildlife while maintaining livestock in semi-arid ecosystems. Wiley-Blackwell, West Sussex, UK, pp 15–29

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

McNew, L.B., Dahlgren, D.K., Beck, J.L. (2023). Introduction to Rangeland Wildlife Ecology and Conservation. In: McNew, L.B., Dahlgren, D.K., Beck, J.L. (eds) Rangeland Wildlife Ecology and Conservation . Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34037-6_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34037-6_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-34036-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-34037-6

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)