Abstract

Effective teaching behaviour is known to be associated with positive pupil outcomes. As such, it is considered an important aspect of educational research. In this chapter, we used validated instruments to measure two types of teaching effectiveness. Teachers’ perceived effective teaching behaviour was measured using the Teacher as Social Context (TASC) questionnaire and teachers’ observed effective teaching behaviour were measured using the International Comparative Analysis of Learning and Teaching (ICALT) Observation Instrument. Statistical comparisons were made between these two measures and were additionally analysed through the lens of teachers’ career phases. The study found that there are significant differences in teachers’ perceived and observed effective teaching behaviour. Teachers’ perceived effective teaching behaviour was found to remain relatively stable throughout their careers, however, their observed effectiveness was seen to change considerably. As teachers enter the middle phases of their careers, an increase in observed effectiveness was identified, followed by a decline during the later career phases. Further analysis of observed effective teaching behaviour using six ICALT domains indicates that the way a teacher facilitates a safe and stimulating learning climate and is efficiently organised plays an important role in the variation of their observed effectiveness. These results have implications for the continued professional development of trainee teachers and qualified teachers at all stages of their careers.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Teacher effectiveness

- Perceived effectiveness

- Observed effectiveness

- Career phase

- Effective teaching behaviour

1 Introduction

Teacher effectiveness has a long tradition of research, with various authors discussing how an effective teacher needs to not only know and understand their students but also the problems they may encounter in their learning. Effective teachers should be able to incorporate their knowledge of students into their classroom practice while respecting and encouraging learners to raise their expectations (e.g. Brown & McIntyre, 1993; Kington et al., 2014; Ruddick et al., 1996; TLRP, 2013; Upton & Taylor, 2014; Wray et al., 2000).

This chapter presents findings from a cross-sectional analysis that explored observed measures of effective teaching behaviour alongside teachers’ self-reported perceptions of their classroom effectiveness obtained using a teacher questionnaire. Focusing on the final wave of data collection, observational data were examined and compared with teachers’ questionnaire responses. Analyses of observed and perceived teaching effectiveness identified variations in practice depending on the length of service (or career phase) of the teacher. In addition, analysis using radar plots suggested that teachers’ effective organisational skills are a key component, acting as a limiting factor to overall teaching effectiveness.

2 Conceptual Framing

2.1 Teacher Effectiveness

An effective education can be defined as improving student achievement (Coe et al., 2014). It is therefore unsurprising that a considerable amount of teacher effectiveness literature focuses on the relationship between teaching and student outcomes. Varying perspectives on the purposes of schooling may affect the priority placed on the different qualities, qualifications, practices, and accomplishments of teachers (Little et al., 2010). There is some agreement that the outcomes of students should not only include new learning, but progression within social, affective and psychomotor domains (Sammons, 1999; Kyriakides & Creemers, 2012); however, to be considered trustworthy, measurements of teacher effectiveness continue to be predominantly based on the academic progress of students (Coe et al., 2014). Consequently, the last few decades have seen the identification of teaching behaviours, teaching skills and other generic features of effective classroom practice which are positively related to student academic achievement (Day et al., 2007; Coe et al., 2014; Kington et al., 2014). For example, teachers’ attributes and actions have been found to be associated with variance in student academic outcomes (Muijs & Reynolds, 2011; Kyriacou, 2018). However, Day et al. (2007), and more recently Muijs et al. (2014), do not limit the characterisation of teacher effectiveness to academic outcomes and suggest that variations in school and classroom contexts (e.g. leadership, culture, colleagues, subject area and socio-economic factors) be used for measuring teacher effectiveness differently. Though the attributes and behaviours of teachers have been firmly integrated into theoretical and empirical models of educational effectiveness for decades (e.g., Creemers & Kyriakides, 2013), they are not easily characterised (Brown et al., 2014) which has potentially contributed to the predominance of teacher effectiveness literature being based on academic outcomes.

Defining teacher attributes and identifying their impact on classroom effectiveness has been linked to perspective (Coe et al., 2014). Literature specifically exploring teachers’ perceptions of their effectiveness has predominantly focused on conceptual and methodological issues pertaining to teachers’ beliefs in their own capability (e.g., Henson, 2010; Klassen et al., 2009; Labone, 2004; Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy, 2001; Wyatt, 2014) and it has been suggested that this sense of self-efficacy in the classroom is an important factor in teachers’ effectiveness (Caprara et al., 2003; Caprara et al., 2006; Aloe et al., 2014). For example, the VITAEFootnote 1 project (Day et al., 2007), which tracked the effectiveness of 300 primary and secondary school teachers over 4 years, found that there was a significant relationship between a teacher’s perceived effectiveness (as reported through questionnaire surveys and interviews) and ‘relative’ effectiveness (as measured through classroom observations and student national test scores). The study also identified that teachers’ perceived effectiveness strongly reflected their overall sense of self-efficacy as a practitioner. Furthermore, their analysis identified that perceived and observed effectiveness were directly affected (to varying degrees) by length of service in the profession which, in turn, affected the way teachers viewed their effectiveness, both positively and negatively, in the classroom (Day et al., 2007).

2.2 Teacher Career Phase

Teachers’ career phases have been categorised in a variety of ways. Super’s (1957) four-stage model suggested that there are distinct phases related to the length of service. Super argued that teachers move through these phases, referred to as exploration, establishment, maintenance and disengagement, although not necessarily in a linear way. Later, Huberman’s (1989) research into secondary school teachers’ career development expanded on Super’s non-linear model and identified that teachers experience five distinct, discontinuous career phases; namely career entry, stabilization, experimentation, conservatism and disengagement (Huberman, 1993). More recently, variations in teachers’ career phases have been further refined through the VITAE project (Day et al., 2007) which developed a six-phase model based on teachers’ professional lives. These phases follow certain discernible patterns characterised by identifiable stages (Day et al., 2007) which are summarised in Table 29.1.

Using the career phase as a conceptual lens, this chapter explores variations between teachers’ perceived effectiveness compared with observations of their practice in England. To this end, three broad research questions were used to guide the analysis:

-

1.

Is there a difference between teachers’ perceived and observed effectiveness?

-

2.

How do perceived and observed effectiveness vary according to teacher career phase?

-

3.

How can variations in observed effectiveness across career phases be explained?

2.3 Research Context

In England, there are five stages of education, namely early years (which includes nursery and pre-school phases), primary school, secondary school, further education (post-16 years) and higher education. This study involved teachers working in primary and secondary schools where the curriculum is further divided into ‘key stages’ based on child age; as such key stages 1 (age 5–6 years) and 2 (age 7–10 years) are covered by the primary stage, whilst key stages 3 (age 11–13 years) and 4 (age 14–16 years) are covered by the secondary stage. General Certificates of Secondary Education (GCSEs) are taken at the end of key stage 4. In England, the majority of state-funded primary and secondary schools are mandated to follow the National Curriculum. However, since 2010, many schools have been granted ‘Academy School’ or ‘Free School’ status which allows more flexibility over the curriculum as well as independence from the local authority with regards to teacher pay and conditions. While academies and free schools have more autonomy over curriculum decisions, all state-funded schools are subject to inspection by the Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted) who expect to find learners studying a full range of subjects by teachers who have ‘good knowledge of the subject’, who ‘present subject matter clearly’, ‘use assessment well’ and ‘create an environment that allows the learner to focus on the learning’ (Ofsted, 2021: 39–40). It is worth noting that across all state-funded schools around 1 in 5 pupils are eligible for free school meals based on their socioeconomic background.

In terms of PISA results, the UK has improved in reading, moving from 25th to 14th amongst OECD countries (OECD, 2021), with England having the highest score of the four UK nations. England is also above the average OECD scores in maths and science, showing an upward trend. England has a young teaching population, with its teachers having spent fewer years in the classroom than teachers in most other TALIS countries (OECD, 2019). The average is 13 years, which ranks 46th out of the 50 countries. Only 18% of the teaching population is over 50 years of age, compared to the OECD average of 34%. Furthermore, practitioners in England report high levels of stress, with 38% of teachers reporting ‘a lot’ of stress in work, compared to the OECD average of 18%. More recently, the OECD reported that the UK had the second highest attrition rate of OECD countries (OECD, 2021).

2.4 Methods and Procedures

This longitudinal study between 2015 and 2019 was conducted through observations of classroom practice, using the International Comparison of Learning and Teaching (ICALT) observation instrument (van de Grift, 2007; van de Grift, 2014), and the Teacher as a Social Context (TASC) questionnaire (Wellborn et al., 1992) which explored teachers’ perceptions of their own practice. The data were collected over 4 years in schools in England, with a growing number of observations conducted each year as increasing numbers of practitioners were recruited to the study. The cross-sectional data reported in this chapter were gathered in the final year of data collection, when a total of 312 lesson observations were carried out, with each teacher observed also completing a teacher questionnaire.

2.5 Instruments

2.5.1 Effective Teaching Behaviour Observations

According to Wragg (1999), classrooms are complex environments representing an interplay of variables that affect observations. The reliability and validity of several established classroom observation instruments have been questioned by various researchers (e.g. Baker et al., 2010; Biesta, 2009; Page, 2016). Furthermore, van de Lans et al. (2016) highlight the particular issue of substantial measurement error, where a judgment of a teacher may not be indicative of their overall performance if, for example, they are working with a difficult class, are feeling ill, and so forth. It could be argued that, in contrast, systematic observation tools such as the ICALT instrument are considered as a valuable method to enable the comparison of teachers’ teaching behaviours; since, in addition to using standardised terms, the instrument includes pre-determined and agreed categories describing elements of observable classroom practice.

The ICALT structured observation schedule consisted of seven domains of teacher effectiveness:

-

1.

A safe and stimulating learning climate – 4 indicators;

-

2.

Efficient organisation – 4 indicators;

-

3.

Clear and structured instructions – 7 indicators;

-

4.

Intensive and activating teaching – 7 indicators;

-

5.

Adjusting instructions and learner processing to inter-learner differences – 4 indicators;

-

6.

Teaching and learning strategies – 6 indicators;

-

7.

Learner engagement – 3 indicators.Footnote 2

This observation tool was piloted, and inter-rater reliability was determined for 10 lessons rated independently by paired researchers. The most appropriate indicator to assess inter-rater reliability for an instrument consisting of ordinal scales, such as the ICALT tool, is the Weighted Kappa and the inter-rater reliability score was statistically significant (mean Weighted Kappa Quadratic = 0.73), which is considered highly reliable (Bakeman & Gottman, 1997). For the main study, observations were conducted by individual researchers and completed during the lesson. Lessons were observed across a range of subjects throughout all key stages (1–4). Each lesson observed lasted between 30 and 60 min. Cronbach’s alpha for the ICALT observation instrument indicated excellent reliability of the scale (α = 0.95).

2.5.2 Teacher Questionnaire

Questionnaires, designed to be administered alongside the ICALT observation tool (Maulana et al., 2014), were distributed to teachers directly after the lesson observations had been conducted, and teachers were asked to complete the survey in relation to the observed lesson. Responses were scored on four-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The questionnaire gathered data according to three areas relating to different aspects of classroom practice.

The questionnaire teacher as a social context (TASC) was used to explore teachers’ perceptions of their effectiveness. The 41 items in this section directly relate to the actions and behaviours of teachers and includes items associated with social aspects of teaching and self-efficacy (e.g. Tschannen-Moran et al., 1998), enabling a self-reported measure of teachers’ perceptions of their effectiveness, with a greater score indicating a higher level of perceived effectiveness. Cronbach’s alpha for the teacher questionnaire indicated good reliability of the scale (α = 0.87).

2.6 Sample

2.6.1 Schools

Schools were varied within the sample and denoted according to the level of education provided (33.00% primary and 67.00% secondary schools). The achieved sample of primary and secondary schools was slightly over-represented in those schools with low socio-economic contexts (as indicated by Free School Meal entitlementFootnote 3) but represented a range of geographical locations (29.17% urban, 60.26% sub-urban, 10.57% rural contexts). Consideration was also given to the number of pupils on the school roll to provide, as far as possible, a representative number of small, medium and large schools. All schools were state-funded.

2.6.2 Teachers

The teacher sample within each school was obtained on an opportunistic basis with those teachers who wanted to participate opting in voluntarily. This resulted in an achieved sample of practitioners who possessed a range of teaching experience, from newly qualified teachers to ‘veteran’ teachers (31+ years). The demographic data were analysed according to the length of service in the profession and these career phase groupings were selected based on Day et al.’s (2007) six phases reflecting variations in teachers’ relative and perceived effectiveness. Against the national profile, the sample included a higher number of teachers in the 8–15 and 16–23 phases, and a lower number of teachers in the 0–3 and 31+ phases. The average length of experience was 17 years (Table 29.2).

Of the 312 teachers, 64.11% were female and 35.98%% were male, compared to figures for England in 2021 of 72.51% female and 27.49% male (Gov.uk, 2021). The gender balance for primary school teachers (75.73% female, 24.27% male) over-represented male teachers (compared to 85.73% female, 14.27% male nationally (Gov.uk, 2021)). However, the sample of secondary school teachers (58.40% female, 41.60% male) slightly under-represented female teachers compared with the national profile (64.60% female, 35.40% male (Gov.uk, 2021)).

2.7 Analysis Strategy

2.7.1 Initial Exploratory Analysis

For each teacher, the mean observed effectiveness was calculated from the mean scores of each of the six teacher-related domains using the data from the ICALT Lesson Observation instrument. Similarly, the perceived effectiveness mean score was calculated from the relevant items of the TASC instrument. The means and standard deviations for both observed and perceived effectiveness were compared. The means were then calculated for groups of teachers according to school phase (primary & secondary) and gender.

Both scores ranged from 1–4, with a higher number indicating a greater effectiveness score. Two null hypotheses were developed to test if there were significant differences between perceived and observed effectiveness scores. The first null hypothesis related to the entire group of teacher participants, whilst the second examined effectiveness through the lens of career phase. These were both tested using an independent samples t-test for significance. Differences in observed effectiveness and perceived effectiveness were further analysed using one-way ANOVA to test for variances within perceived and observed effectiveness.

2.7.2 Scatter Graph Analysis

Scattergrams were plotted to explore differences in teacher observed and perceived effectiveness across all six career phases. Analysis was carried out by eye to determine clusters of scores for teachers using arbitrary measures of high, intermediate and low effectiveness. Outliers were discarded from the analysis and the mean scores for both observed and perceived effectiveness then calculated for each cluster.

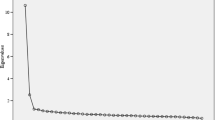

2.7.3 Radar Plot Analysis

The initial exploratory analysis led to a deeper investigation of observed and perceived effectiveness through the ICALT and TASC domains, using radar plots to depict the multivariate data as described by Saary (2008). The aim was to identify if variations existed in each of the six ICALT domains (excluding engagement) across the career phases of the participants. Mean averages were calculated for participants in each domain across all six career phases and presented on radar plots. Each plot examined a different career phase and consisted of six axes, depicting each of the ICALT domains. This allowed for subtle differences in overall scores and scores for each domain to be highlighted. Points closer to the origin of the plot denote a lower observed effectiveness, whilst those further away depict greater levels of observed effectiveness. The uniformity of the hexagon shape produced describes the relative scores for each domain. For example, a profile where domain scores were of an equal magnitude would result in a perfect hexagon. When scores varied in magnitude, the hexagon shows distortions at the vertices.

The following section reports the results of these analyses, illustrating how the three research questions were addressed.

3 Results

3.1 Is There a Difference Between Teachers’ Perceived and Observed Effectiveness?

A null hypothesis, stating that there was no significant change, on average, between a teacher’s observed and perceived effectiveness was tested to explore variations in effectiveness. An independent samples t-test was conducted to look for a significant difference between observed and perceived effectiveness (Table 29.3).

The t-test showed that there is a 95% confidence level (t(311) = 29.4, p = <0.5) that observed effectiveness is significantly greater than perceived effectiveness in the sample of participants. This shows that teachers perceive their effectiveness to be significantly lower than it is observed to be.

3.2 How Do Perceived and Observed Effectiveness Vary According to Teachers’ Career Phase?

To further explore variations in observed and perceived effectiveness, a second null hypothesis was tested – that there was no significant change between a teacher’s observed and perceived effectiveness across the six career phases (Table 29.4).

T-tests were conducted across each career phase to test the null hypothesis. The t-tests showed that there was a 95% confidence level that observed effectiveness is significantly greater than perceived effectiveness in each of the separate career phases, apart from in the earliest phase (0–3 years), where there was no statistical difference.

To examine this more closely, perceived effectiveness, as measured by the questionnaire, was plotted against observed effectiveness, determined by observation. Figure 29.1 shows three clusters of data, characterised as follows:

-

High perceived (M = 2.9) and high observed effectiveness (M = 3.5)

-

Low perceived (M = 2.7) and intermediate observed effectiveness (M = 3.2)

-

Low perceived (M = 2.5) and low observed effectiveness (M = 2.5)

The analysis identified that the early career teachers in the 0–3 phase (light blue) and 4–7 phase (orange) were situated in the low perceived and low observed effectiveness cluster. Mid-career teachers (8–15 years & 16–23 years, shown in grey and yellow respectively) were present in the high perceived and high observed effectiveness cluster. Finally, late-career teachers in the 24–30 (dark blue) and 31+ phases (green) were present in both low and intermediate observed effectiveness clusters and low perceived effectiveness. Since the clusters are distinct and represented by the majority of teachers in each of the phases, this strongly suggests that career phase may contribute to teacher effectiveness.

The variation in observed effectiveness and relatively stable scores in perceived effectiveness were further analysed using one-way ANOVA to test for variances within perceived and observed effectiveness between the six career phases (Tables 29.5 and 29.6).

The F value for perceived effectiveness scores (170.3) was above the critical value of 3.02 indicating that there were significant differences in mean perceived effectiveness across the career stages. The F value for observed effectiveness scores (1122.5), was also above the critical value, showing significant differences in mean observed effectiveness. However, the F value for observed effectiveness was far greater than the value for perceived effectiveness, indicating that whilst there was variation within perceived effectiveness scores, the variation in observed effectiveness scores was much larger.

3.3 How Can Variations in Observed Effectiveness across Teachers’ Career Phases Be Explained?

As described earlier, mean averages for each of the six ICALT domains were calculated and displayed on radar plots for each of the six career phases. Figures 29.2 a and b show these plots for the earliest career phases, 0–3 years and 4–7 years experience.

Figures 29.2 a and b illustrate the differences in observable teaching behaviours by early career teachers (phases 0–3 years and 4–7 years). It can be seen that overall, they display significantly lower overall scores for all teaching behaviours (0–3 years: M = 2.31, N = 8; 4–7 years: M = 2.46, N = 50) in comparison to both mid-career phases, (8–15 years: M = 3.57, N = 101; 16–23 years M = 3.57, N = 76) and late-career teachers, (24–30 years: M = 3.21, N = 39; 31+ years: M = 2.68, N = 38) (see Figs. 29.3 and 29.4 below for more details). The distorted hexagonal plot represents variations within the observable teaching behaviours for the early career teachers; for example, the ability of the teachers to foster a safe and stimulating learning climate and enact efficient organisation were depressed in 0–3 years in comparison with other observable indicators of teacher behaviour (see plot 2i). In the case of the 4–7 years career phase, the overall pattern was more evenly distributed as represented by a near regular hexagon, with only slight depressions visible for the same indicators.

The profile represented by the radar plots for the mid-career phases teachers (8–15 years and 16–23 years) shows considerable differences to those for the other career phases.

Figures 29.3 a and b illustrate the differences in observable teaching behaviours by mid-career teachers (phases 8–15 years and 16–23 years). Overall, it can be seen that they display much higher scores than those in both the earlier and later career stages (see Figs. 29.2 and 29.4) with an overall mean of 3.57 (N = 177). The regular hexagonal plot represents the absence of discernible variations within the highly scoring observable teaching behaviours for the middle career phases.

Again, the radar plots show teachers tend to experience another change as they enter the later career phases (24–30 years and 31+ years).

Figures 29.4 a and b illustrate the differences in observable teaching behaviours by later career teachers (phases 24–30 years and 31+ years). It can be seen that overall, they display an intermediate level of overall scoring (higher than that for the earlier career phases but lower than that for the middle career phases) for all teaching behaviours with an overall mean of 3.21 (N = 77).

The distorted hexagonal plots represent variations within the observable teaching behaviours for the later career teachers. For example, the ability of the teachers to provide intensive and activating teaching and adjust instructions to learners are comparatively higher within the scores of the 24–30 years (see plot 4i). Although the scores for the 31+ years teachers show the same overall profile as the 24–30 years (as demonstrated by the same shape of an irregular hexagon), the overall scores are seen to be slightly lower (24–30 years: M = 3.21, N = 39; 31+ years: M = 2.68, N = 38).

4 Conclusions and Implications for Practice

The analysis of data reported here has shown how teachers’ perceptions of their effectiveness and their observed effectiveness vary depending on the length of service. It has been shown that teachers perceive their effectiveness to be significantly lower than it is observed to be, suggesting that teachers underestimate their proficiency. This is a phenomenon that has not been explored in any depth in previous literature. In a study examining the differences between perceived and measured teaching effectiveness, Sadeghi et al. (2020) found inconsistencies between the two measures. Their study, using different instruments to measure perspectives on effectiveness for eight participants, found varied results. Two participants rated their perceived effectiveness lower than their observed effectiveness score. The remaining six participants rated themselves to be more effective than observed, highlighting the inconsistencies in self-rated measures. Conversely, results from the current study suggest that teachers consistently under-rate their performance.

When examined across the six career phases, the statistically significant differences between observed and perceived effectiveness for all participants of this study were replicated for all but one career phase. Despite all participants showing effective teaching to varying degrees, teachers in the 4–7, 8–15, 16–23, 24–30 and 31+ phases were found to perceive their effectiveness significantly lower than it was observed as being. Teachers in the earliest career phase (0–3) were found to have no statistical difference between their observed and perceived effectiveness. This could be because this group of teachers have recently completed their teacher training and are therefore more familiar with observational feedback on their effectiveness (Koni & Krull, 2018; Uhrmacher et al., 2013). However, caution is needed when interpreting the data for this group as there were only eight participants in the 0–3 career phase which might explain this anomaly.

Although the one-way ANOVA test showed statistical differences across the six career phases for both perceived and observed effectiveness, the level of significance in observed effectiveness was higher. The level of observed effectiveness rose to its highest in the mid-career phases (8–15 & 16–23), before decreasing in the late-career phases (24–30 & 31+). This could be explained by the ‘disengagement stage’ later career teachers have been found to experience (Day et al., 2007; Huberman, 1993; Veldman et al., 2017). T-tests confirmed this by identifying the greatest differences in observed versus perceived effectiveness for the mid-career phases (8–15 years, t(100) = 85.1, p = <0.5; 16–23 years, t(75) = 74.3, p = <0.5). It suggests that mid-career teachers’ perceptions of effectiveness do not change dramatically, unlike their observed effectiveness, which increases to the highest levels of all the career phases. Similarly, although the late-career teachers experience decreased observed effectiveness, their self-reported perceptions of effectiveness are still significantly lower (24–30 years, t(38) = 47.9, p = <0.5; 31+ years, t(37) = 22.9, p = <0.5). Interestingly, although those in the later career stages perceive their effectiveness to decline to similar levels to that of career phase 4–7 years (M = 2.31), their observed effectiveness remains significantly above their early career counterparts.

Examination of the six ICALT domains of observed teaching identified that whilst effective teaching behaviour increases as teachers enter the middle phases of their careers, some domains increase more rapidly than others. In the earlier career phases, there is a great variation in the scores for each domain, which is no longer present in the middle career phases. The comparatively low efficient organisation scores for 0–3 and 4–7 career phases indicate that these teachers are less effective at organising and structuring their lessons. Teachers in the 8–15 career phase were observed as having high levels for all six domains and this level is maintained by those in the 16–23 phase. However, this changed for teachers in the penultimate career phase (24–30), where safe and stimulating learning climate and efficient organisation scores decreased at a greater rate than the other domains. This decrease continues into the final phase (31+) when a decline in the remaining four domains is also observed.

The data suggest that efficient organisation is a limiting component for observed teacher effectiveness. At the start of teachers’ careers, efficient organisation is limiting overall effectiveness. By the time a teacher is well established, efficient organisation rises to equal levels of all six ICALT domains. The decline seen in teacher effectiveness towards to end of their careers (Day et al., 2007; Huberman, 1993; Veldman et al., 2017) is shown here to be due to a decline in safe and stimulating learning climate and efficient organisation. These domains fall before the others, suggesting this drop might be a causative factor in the overall decline in observed teacher effectiveness.

In summary, the study found that there was a difference in teachers’ perceived and observed effectiveness and that these appear to according to career phase. Analyses also demonstrated that these variations are associated with how teachers structure their classrooms and plan for the learning experiences of pupils. These results have implications for teachers at all stages of their career. For example, early-career teachers need to reflect on their opportunities to create and articulate explicit elements of structure and organisation within their lessons to build on increasing perceptions of classroom effectiveness. This is also crucial in retaining these practitioners in the profession. Mid-career teachers should critically engage with ways in which they can support colleagues (Lai & Lam, 2011; Mutton et al., 2011) to maintain and develop structural elements of practice, thereby affording students additional choice within lessons (Reeve & Cheon, 2021). Finally, teachers in the late-career phases could consider how to maintain a safe and stimulating learning climate and efficient organisation. Given the overall downward trajectory of effectiveness for teachers at this point in their career, professional development could play an important factor for this group to maintain the commitment of these experienced practitioners (Brunetti & Marston, 2018).

Notes

- 1.

Variations in Teachers’ Work, Lives and Effectiveness, commissioned by the Department for Education and Skills.

- 2.

This domain was not included in the analysis presented here, as it was not directly associated with teacher behaviours

- 3.

Free School Meal (FSM) entitlement was used as a proxy for socio-economic context of the schools. There were four categories as follows: FSM 1 describes schools with 0–8% of pupils eligible for free school meals. This percentage rises to 9–20% for FSM 2 schools, 21–35% for FSM 3 schools and over 35% for FSM 4 schools.

References

Aloe, A., Amo, L., & Shanahan, M. (2014). Classroom management self-efficacy and burnout: A multivariate meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 26, 101–126.

Bakeman, R., & Gottman, J. (1997). Observing interaction: An introduction to sequential analysis (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Baker, E., Barton, P., Darling-Hammond, L., Haertel, E., Ladd, H., & Linn, R. (2010). Problems with the use of student test scores to evaluate teachers [Press release]. https://www.epi.org/publication/bp278/

Biesta, G. (2009). Good education in an age of measurement: On the need to reconnect with the question of purpose in education. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21(1), 33–46.

Brown, S., & McIntyre, D. (1993). Making sense of teaching. Open University Press.

Brown, P., Roediger, H., III, & McDaniel, M. (2014). Make it stick: The science of successful learning. Harvard University Press.

Brunetti, G. J., & Marston, S. H. (2018). A trajectory of teacher development in early and mid-career. Teachers and Teaching, 24(8), 874–892.

Caprara, G., Barbaranelli, C., Borgogni, L., & Steca, P. (2003). Efficacy beliefs as determinants of Teachers’ job satisfaction. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(4), 821–832.

Caprara, G., Barbaranelli, C., Steca, P., & Malone, P. (2006). Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs as determinants of job satisfaction and students’ academic achievement: A study at the school level. Journal of School Psychology, 44(6), 473–490.

Coe, R., Aloisi, C., Higgins, S., & Major, L. (2014). What makes great teaching? Review of the underpinning research. Sutton Trust. https://dro.dur.ac.uk/13747/1/13747.pdf

Creemers, B., & Kyriakides, L. (2013). Using the dynamic model of educational effectiveness to identify stages of effective teaching: An introduction to the special issue. The Journal of Classroom Interaction, 48(2), 4–10.

Day, C., Stobart, G., Sammons, P., & Kington, A. (2007). Variations in the work and lives of teachers: Relative and relational effectiveness. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 12(1), 169–192.

Gov.uk. (2021). School workforce in England. https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-workforce-in-england

Henson, R. (2010). From adolescent angst to adulthood: Substantive implications and measurement dilemmas in the development of teacher efficacy research. Educational Psychologist, 37(3), 137–150.

Huberman, M. (1989). The professional life cycle of teachers. Teachers College Record, 91(1), 31–57.

Huberman, M. (1993). Steps toward a developmental model of the teaching career. In L. Kremer-Hayon, H. Vonk, & R. Fessler (Eds.), Teacher professional development: A multiple perspective approach (pp. 93–118). Swets and Zeitlinger.

Kington, A., Sammons, P., Regan, E., Brown, E., Ko, J., & Buckler, S. (2014). Effective classroom practice. Open University Press.

Klassen, R., Bong, M., Usher, E., Chong, W., Huan, V., Wong, I., & Georgiou, T. (2009). Exploring the validity of a teachers’ self-efficacy scale in five countries. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 34(1), 67–76.

Koni, I., & Krull, E. (2018). Differences in novice and experienced teachers’ perceptions of planning activities in terms of primary instructional tasks. Teacher Development, 22(4), 464–480.

Kyriacou, C. (2018). Essential teaching skills (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Kyriakides, L., & Creemers, B. (2012). School policy on teaching and school learning environment: Direct and indirect effects upon student outcome measures. Educational Research and Evaluation, 18(5), 403–424.

Labone, E. (2004). Teacher efficacy: Maturing the construct through research in alternative paradigms. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(4), 341–359.

Lai, E., & Lam, C. C. (2011). Learning to teach in a context of education reform: Liberal studies student teachers’ decision-making in lesson planning. Journal of Education for Teaching, 37(2), 219–236.

Little, J., Bartlett, L., Mayer, D., & Ogawa, R. (2010). The teacher workforce and problems of educational equity. Review of Research in Education, 34(1), 285–328.

Maulana, R., Van de Grift, W., & Helms-Lorenz, M. (2014). Development and evaluation of a questionnaire measuring pre-service teachers’ teaching behaviour: A Rasch modelling approach. School Effectiveness and School Improvement., 26(2), 169–194.

Muijs, D., & Reynolds, D. (2011). Effective teaching. Evidence and practice (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Muijs, D., Kyriakides, L., van der Werf, G., Creemers, B., Timperley, H., & Earl, L. (2014). State of the art teacher effectiveness and professional learning. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 25(2), 231–256.

Mutton, T., Hagger, H., & Burn, K. (2011). Learning to plan, planning to learn; the developing expertise of beginning teachers. Teachers and Teaching, 17(4), 399–416.

OECD. (2019). TALIS 2018 results (volume I): Teachers and school leaders as lifelong learners, TALIS. OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2021). 21st-century readers: Developing literacy skills in a digital world, PISA. OECD Publishing.

Ofsted (Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills). (2021). Education inspection framework. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/education-inspection-framework/education-inspection-framework

Page, L. (2016). The impact on lesson observations on practice, professionalism and teacher identity. In M. O’Leary (Ed.), Reclaiming lesson observation: Supporting excellence in teacher learning (pp. 62–74). Routledge.

Reeve, J., & Cheon, S. H. (2021). Autonomy-supportive teaching: Its malleability, benefits, and potential to improve educational practice. Educational Psychologist, 56(1), 54–77.

Ruddick, J., Chaplain, R., & Wallace, G. (1996). School improvement: What can pupils tell us? D Fulton Publishers.

Saary, J. (2008). Radar plots: A useful way for presenting multivariate health care data. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 61(4), 311–317.

Sadeghi, K., Richards, J. C., & Ghaderi, F. (2020). Perceived versus measured teaching effectiveness: Does teacher proficiency matter? RELC Journal, 51(2), 280–293.

Sammons, P. (1999). School effectiveness: Coming of age in the 21st century. Management in Education, 13(5), 10–13.

Super, D. (1957). The psychology of careers. Harper.

TLRP (Teaching and learning research programme). (2013). TLRP: Ten principles. www.tlrp.org/themes/themes/tenprinciples.html.

Tschannen-Moran, M., Woolfolk Hoy, A., & Hoy, W. (1998). Teacher efficacy: Its meaning and measure. Review of Educational Research, 68(2), 202–248.

Tschannen-Moran, M., & Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17, 783–805.

Uhrmacher, P. B., Conrad, B. M., & Moroye, C. M. (2013). Finding the balance between process and product through perceptual lesson planning. Teachers College Record, 115(7), 1–27.

Upton, P., & Taylor, C. (2014). Educational psychology. Pearson.

van de Grift, W. (2007). Quality of teaching in four European countries: A review of the literature and application of an assessment instrument. Educational Research, 49(2), 127–152.

van de Grift, W. (2014). Measuring teaching quality in several European countries. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 25(3), 295–311.

van de Lans, R., van de Grift, W., van Veen, W., & Fokkens-Bruinsma, M. (2016). Once is not good-enough: Establishing reliability criteria for feedback and evaluation decisions based on classroom observations. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 50(1), 88–95.

Veldman, I., Admiraal, W., Mainhard, T., Wubbels, T., & van Tartwijk, J. (2017). Measuring teachers’ interpersonal self-efficacy: Relationship with realized interpersonal aspirations, classroom management efficacy and age. Social Psychology of Education, 20(2), 411–426.

Wellborn, J., Connell, J, Skinner, E., & Pierson, L. (1992). Teacher as social context (TASC). Two measures of teacher provision of involvement, structure and autonomy support. [Technical report]. University of Rochester.

Wragg, E. (1999). An introduction to classroom research. Routledge.

Wray, D., Medwell, J., Fox, R., & Poulson, L. (2000). The teaching practices of effective teachers of literacy. Educational Review, 53(1), 75–84.

Wyatt, M. (2014). Towards a reconceptualization of teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs: Tackling enduring problems with the quantitative research and moving on. International Journal of Research and Method in Education, 37(2), 166–189.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the schools, teachers and pupils who participated in this study. Thanks also to the University of Worcester for its continued support of the research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Looker, B., Kington, A., Hibbert-Mayne, K., Blackmore, K., Buckler, S. (2023). The Illusion of Perspective: Examining the Dynamic Between Teachers’ Perceived and Observed Effective Teaching Behaviour. In: Maulana, R., Helms-Lorenz, M., Klassen, R.M. (eds) Effective Teaching Around the World . Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31678-4_29

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31678-4_29

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-31677-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-31678-4

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)