Abstract

This book chapter reports findings in a case study on the video clips of 97 STEM lessons at a local secondary school. The impact of Effective and inspiring teaching on student engagement in classrooms was explored using the same high-inference classroom observation instruments. Cluster analysis indicated that effective teaching dimensions tended to cluster together. However, inspiring teaching dimensions (i.e., Flexibility, Innovative teaching, and Teaching reflective thinking) tended to cluster with Teaching collaborative learning. While there was no subject difference for inspiring teaching practices, Mathematics significantly performed the best and Technology the worst in effective teaching practices. Multiple regression results indicated that both effective and inspiring teaching practices have a significant but moderate impact on learner engagement, but none showed significant effects on student engagement. In contrast, while the effective teaching dimension Professional knowledge and expectations positively affected overall teaching quality perceptions.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

This study represents a classroom observation approach to capture rich information about classroom behaviours and activities through instruments developed to observe generic teaching behaviours across subjects, grades, and contexts. The research comparing effective and inspiring teaching is justified because the conceptual boundary between effective teaching and inspiring teaching was unclear, indicating a theoretical overlap (Sammons et al., 2014). An instrument comparison was adopted as a methodology strategy because of previous international studies (e.g., Kington et al., 2014; Kane & Stagier, 2012; Kane et al., 2011; Sammons et al., 2014). Another methodology strategy was to limit the lesson sample to a single school. This strategy was also adopted in the previous projects to illuminate the rich variations across departments within a school suggested by Sammons et al. (1997).

2 Theoretical Background

This study extended empirical works on teacher effectiveness (Kington et al., 2014; Ko et al., 2015; Ko et al., 2016; Sammons et al., 2014). The following sections examine three interrelated issues: the comparisons between effective and inspiring teaching, classroom observations with high-inference instruments, and contextual influences on teaching quality variations.

2.1 Characteristics of Inspiring Teachers and Relations with Effective Teaching

Compared to the vast amount of literature on teacher effectiveness (see Ko & Sammons, 2013; Hattie, 2009), inspiring teaching is minimal. Harmin and Toth (2006, p.16) outlined some professional characteristics of inspiring teachers, but they suggested what these teachers might do in the classroom. Inspiring teachers may make a lesson more inspiring through four steps: targeting (i.e., “maintain clear standards for themselves with a strong sense of their ideals and directions”), adjusting (i.e., “able to adjust their teaching when they choose to do so and not reluctant to explore something new if they sense it might help them better serve their ideals”), balancing (i.e., “maintain a fair measure of personal balance in their work”), and supporting (i.e., “willing to share ideas and talk with colleagues about professional questions, including their personal confusions and weaknesses.”

In England, Sammons et al. (2014) conducted a study to explore inspiring teaching and found that inspiring teachers shared many effective teachers’ characteristics. Based on the lesson observations of 17 inspiring primary and secondary teachers, Sammons et al. (2016, p. 136) found many practices and behaviours typically associated with highly effective teaching included:

-

Creating a positive, safe, and supportive climate for learning

-

Managing behaviour, space, time, and resources efficiently and effectively

-

Implementing clear instruction, including explicit and high expectations and objectives for learning

-

Demonstrating good behaviour management skills and efficient use of learning time

-

Skilful use of questioning and feedback to make lessons highly interactive and extend learning.

In addition, inspiring teachers were found to be:

-

Using largely informal approaches to meet individual student needs

-

Promoting high levels of student engagement and motivation through varied learning activities and arrangements

-

Seeking ways to promote and honour student choice and input

-

Using a wide variety of activities or approaches throughout a lesson

-

Showing high levels of commitment and care for students’ learning and well being

-

Developing and reinforcing positive relationships with students

Sammons et al. (2014, p.16) pointed out that their participant teachers considered that “inspiring and being effective were two related and mutually-dependent aspects of teaching” such that “being inspiring was much more due to the link with relationships.” For example, like their effective colleagues, inspiring teachers can also develop a positive relationship with students, making their lessons more enjoyable, stimulating and engaging (Sammons et al., 2014). Effective teachers can make their lessons engaging through better structuring and stronger connections between the learning activities with students’ daily experiences (Ko et al., 2015). However, inspiring teachers seem to achieve similar influences on students through stronger personal connections with students, simultaneously mixing well three aspects of teaching Positive classroom management, Enthusiasm for teaching, and Positive relationships with children (Fig. 26.1).

Characteristics of inspiring teachers in Sammons et al. (2014)

Sammons et al. (2014, 2016) did not develop any instrument to distinguish the classroom practices of inspiring teachers. Instead, they used the same instruments used in Kington et al., 2014), which are more appropriate to capture effective teachers’ generic teaching characteristics. Motivated to address the lack of a valid classroom observation instrument to measure and characterise the similarities and differences between effective and inspiring teaching quantitatively, Ko et al. (2016, 2019a, b) conceptualised three aspects of teaching behaviours in Fig. 26.1 more explicitly related to inspiring teaching: Innovative Teaching, Flexibility, Reflectiveness and Collaboration. For example, inspiring teachers are often more willing to develop stronger collaborations and offer more support than colleagues than other teachers (Sammons et al., 2014). International research by OECD indicated that teacher collaboration helps support teacher reflection and thus forms an essential feature of professional practice (Vieluf et al., 2012). Pedagogical innovations are also strongly associated with teachers’ reflections through professional collaborations with other teachers (Vieluf et al., 2012).

Based on a secondary analysis of 206 lesson videos selected from 306 Hong Kong lessons of the 538 lessons by Ko et al. (2015), Ko et al. (2016, 2019a, b) identified two clusters in hierarchical cluster analysis results. Cluster 1 with eight factors represents Effective Teaching: Enthusiasm for teaching, Positive relationships with students, Purposeful and relevant teaching, Safe classroom climate, Stimulating learning environment, Positive classroom management, Assessment for learning, and Professional knowledge and expectations. Cluster 2 indicates Inspiring Teaching with factors: Flexibility, Teaching reflective thinking, and Innovative teaching.

2.2 Classroom Observation Using High-Inference Instruments

High-inference classroom observation instruments are often preferable in classroom research. While high-inference instruments are generally more subjective, they are much more cost-effective to conduct than low-inference instruments. High-inference instruments require the observer to make high inferences or judgements about the behaviours and their impacts observed in the classroom (Muijs & Reynolds, 2017; O’Leary, 2020; Schaffer et al.,1994).

Among the two low-inference and three high-inference instruments that Ko et al. (2015) compared, the International Comparative Analysis of Teaching and Learning (ICALT) (formerly known as the Quality of Teaching Scale; van de Grift 2007, van de Grift et al., 2014) were found distinguishing effective teaching behaviours more clearly. By conducting secondary data analysis of the same set of video-recorded lessons with a similar high-inference observation instrument specifically for measuring inspiring teaching, Ko et al. (2016, 2019a, b) developed a new high-inference instrument to compare effective and inspiring teaching with the generic behavioural characteristics of effective teachers characterised in the ICALT. Thus, this study can extend Ko et al.’s (2016, 2019a, b) work to examine effective and inspiring teaching in STEM subjects of a school, which is presumably a more confined context.

2.3 Contextual Influences on Variations of Teaching Quality

In the literature, while variations across schools in an education system are often the focus of school effectiveness research, Sammons et al. (1997) showed that within-school variations were often more extensive than between-school variations. Effective departments exist in ineffective schools, while effective departments also exist ineffective schools. Ko (2010) noted that considerable variations existed in the same teachers’ different classrooms because teaching consistency is hard to maintain teaching effectiveness or some teachers who seemed to struggle with teaching specific student groups like students with special needs or affected by the washback effect of the public examination.

An empirical work by Opdenakker and Van Damme (2007) suggested significant influences of school context, student composition and school leadership on school practice and outcomes in secondary education. Contextual effects on effective teaching were inconclusive (Ko et al., 2015). While no city showed a dominance of effective or less effective teachers, considerable differences in the school sector, subject, and location contrasts were evident (Ko et al., 2015). Interestingly, the teaching effectiveness patterns of highly effective and highly ineffective teachers in different cities look alike. Studies in China (e.g., Li, 2015; Walker et al., 2012) showed the increasingly significant role of school principals in China in promoting schools’ pedagogical innovations. Chinese teachers also participated in professional development and led research to enhance teaching and learning more often than Hong Kong teachers. These results suggest that we need to develop an appropriate interview protocol that goes beyond investigating the teaching practices of Hong Kong and Guangzhou schools but looks into the impact of broader educational contexts and the characteristics within schools such as leadership, instructional management, department and school policies.

2.4 Research Questions

To explore the overlapping relationships between effective and inspiring teaching, I continued to adopt the instrument strategy in addressing the following research questions:

-

1.

What specific teaching behaviours/dimensions can be characterised as inspiring in the observed STEM classrooms?

-

2.

Are there differences in teaching quality among different STEM subjects?

-

3.

Do effective teaching and inspiring teaching impact student engagement?

-

4.

Do effective teaching and inspiring teaching impact perceptions of overall teaching quality?

3 Methods

3.1 Samples

As a case study of a single local English medium secondary school in Hong Kong, the lesson video sample consisted of 97 lessons in four STEM subjects: Mathematics, Science, Technology, and Personal, Social and Health Education (PSHE). The academic attainment of the school is about the top one-third. Despite a tuition fee of about HK3000 per month, the subscription is keen among families with middle socio-economic backgrounds in the district. The school initially videotaped all lessons for internal teacher evaluation and professional development purposes. Ethical consent forms were obtained through the school administration.

3.2 Instruments

The two classroom observation instruments employed in this study were the same as those in Ko et al. (2016, 2019a, b). Both instruments were high-inference by nature, requiring the subjective judgements of the raters. ICALT was well established and validated across many countries (Maulana et al., 2020), but CETIT also has high reliability and validity (Ko, Sammons & Kyriakides, 2016).

3.2.1 International Comparative Analysis of Teaching and Learning (ICALT)

Originated as an instrument for inspections, the International Comparative Analysis of Learning and Teaching (ICALT) (van de Grift, 2014) was an instrument that combined low and high-inference components. Raters have to indicate the absence or presence of teaching behaviours associated before rating the teacher performance along 32 teaching indicators to determine their strengths on a 4-point scale, from ‘mostly weak’ to ‘mostly strong’. As depicted in Table 26.1, these teaching indicators are theoretically grouped further into six domains: Safe and stimulating learning climate, Efficient organisation, Clear and structured instructions, Intensive and activating teaching, Adjusting instructions for learner differences, and Teaching learning strategies. For the ease of associating teaching behaviours with student engagement during classroom observations, the ICALT also contained a three-item (e.g., “…take an active approach to learn”) domain to document learner engagement.

3.2.2 Comparative Analysis of Effective Teaching and Inspiring Teaching (CETIT)

Ko et al. (2016) used the Delphi method to finalise 68 items and validated a new high-inference classroom observation instrument with 12 teaching aspects of effective and inspiring teaching behaviours. Ten of the 12 aspects were identified qualitatively by Sammons et al. (2014). Ko et al. (2016) hypothesised that Flexibility, Teaching reflective thinking, Innovative teaching, and Teaching collaborative learning. Respective examples of teaching behaviours were “The teacher allowed options for students in their seatwork,” “The teacher asked students to comment on his/her viewpoint,” “The teacher used ICT in teaching,” “The teacher told students how to share their work in a task.”

Reflectiveness and collaboration were considered characteristics of inspiring teachers in Sammons et al.’s (2014) study. However, Ko et al. (2016) considered inspiring teachers to promote collaborative learning and develop students’ reflective thinking as two distinctive classroom practices. They also distinguished a safe and stimulating classroom climate as they could be conceptually and empirically different in some studies (e.g., van de Grift, 2007). Assessment for learning and Professional knowledge and expectations were not studied previously (Kyriakides & Creemers, 2008; Day et al., 2008; Ko et al., 2015) but were included for their potential to extend the existing models of teacher effectiveness empirically (Table 26.2).

3.3 Raters

Four research assistants with varied research experience in classroom observation observed the lesson videos after calibrations with training videos and two lesson videos in the sample. They had to discuss the discrepancies in evaluations. Experience, training and calibration were crucial for achieving high reliability. Inter-rater reliability of .79 was achieved before they started to do observation independently.

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive Statistics

Table 26.3 summarises the mean, standard deviation, and reliability of each teaching dimension of the two instruments, CETIT and ICALT. It is not surprising that Positive classroom management, Safe classroom climate, and Safe and stimulating learning climate have the highest means, while Flexibility, Adjusted instruction for catering to learner diversity, and Teaching learning strategy have the lowest means. Because in line with the research literature, these dimensions represent the most straightforward and most challenging aspects of teaching. Most standard deviations are not high, except for Teaching collaborative learning. Most teaching dimensions’ reliability scores were well above .7, ranging from .7 to .93, indicating good reliability except for Adjusted instruction for catering to learner diversity, which has an alpha of .41, below the acceptable reliability of .7 for a scale in education research (Taber, 2017).

Table 26.4 summarises the two-tailed Pearson correlations between the CETIT dimensions and the ICALT dimension Learner engagement and the judgement of Overall teaching quality. Among all teaching dimensions, Flexibility and Innovative teaching are least likely to be associated with other teaching dimensions, including Professional knowledge and expectations, suggesting inspiring teaching practices do not necessarily require professional solid content knowledge. However, Flexibility is correlated significantly with Teaching reflective thinking and Positive relationships with students, suggesting teaching students reflective thinking may require some flexibility (or ‘thinking out of the box’ attitude) and reflects positive relationships with students. Teachers sometimes may have to be flexible for teaching students collaborative learning or assessing them for learning. The cost of being flexible would be an impression of ‘poor’ classroom management or ‘ineffective’ organisation, as indicated by the significant negative correlations between these teaching dimensions.

4.2 Categorisation of Effective and Inspiring Teaching Behaviours

We decided the clusters using average linkage to estimate the distance among factors, which overcomes the shortcoming of single and complete linkage (Yim & Ramdeen, 2015). Based on the Agglomeration Coefficients of hierarchical cluster analysis conducted with SPSS version 24, the results suggested the clustering process should stop or stay at stage 8 (Table 26.5. and Fig. 26.2). By stopping the clustering at this point, the factors were clustering into four categories (Fig. 26.3).

Hence, grouping dimensions Safe classroom climate, Professional knowledge and expectations, Positive classroom management, Enthusiasm for teaching, Purposeful and relevant teaching, Stimulating learning environment, Assessment for learning and Positive relationship with students formed the first cluster. Dimensions Flexibility and Reflectiveness were grouped as the second cluster. Innovative teaching and Teaching collaborative learning were two isolated clusters.

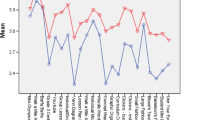

4.3 Differential Teaching Behaviours Among STEM Subjects

As depicted in Table 26.6, the means between the two instruments seemed to show similar patterns since the Mathematics lessons had the highest means. In contrast, regardless of instruments, Technology lessons had the lowest, except for that the ICALT average for Science lessons was higher than that for PSHE lessons, but vice versa for the average for the CETIT-effective teaching component. There was no subject difference for the CETIT (F(3,96) = 2.522, p = .063). However, there is a significant difference in the ICALT among four subjects (F(3,96) = 12.18, p < .001).

However, when instrument comparisons were narrowed down into details where the effective teaching component and the inspiring component of the CETIT were separate, the results showed exciting distinctions. First, there was a significant difference in the CETIT-effective teaching component among four subjects (F(3,96) = 5.08, p < .001). Second, while the CETIT-inspiring teaching component’s variations remained insignificant (F(3,96) = 1.37, p = .256), Technology lessons had the highest mean because more innovative teaching was found in this subject. These results suggested that while both the ICALT and the CETIT-effective teaching component could distinguish the teaching quality of four subjects, the CETIT showed more variations at the teaching dimension level.

4.4 Impact of Effective Teaching and Inspiring Teaching on Student Engagement

Multiple regression analysis in SPSS version 24 was performed to explore the relative significance of the effective and inspiring teaching dimensions of CETIT in predicting student engagement. Learner engagement of ICALT was used as the dependent variable. The eight theoretical dimensions of effective teaching were entered first, followed by the four inspiring teaching dimensions to test the hierarchical models. Effective teaching practices had a significant but moderate impact (R2 = .32 for Model 1, p < .001, effective teaching practices alone), but additional inspiring teaching component had an insignificant impact on learner engagement (F = 1.174, p = .328 for Model 2, both effective and inspiring teaching practices) (Table 26.7). None of the individual teaching dimensions was found to impact student engagement significantly. As results indicated that the basic constant model was significant, other factors such as subject differences might affect student engagement. As there were many variables in building both models, multicollinearity might have also affected the modelling results.

4.5 Impact Effective Teaching and Inspiring Teaching on the Overall Perception of Teaching Quality

Contrary to the results showing no significant impact of individual teaching dimensions on student engagement, models in Table 26.8 indicated significant effects of effective and inspiring teaching dimensions. While Positive classroom management (β = .258) and Professional knowledge and expectations strongly affected student engagement positively, the latter’s strength was stronger (β = .42) (R2 = .652, F (8, 96) = 1.594, p < .001 for Model 1, effective teaching component only). However, when inspiring teaching dimensions were added as predictors (R2 = .722, F (12, 96) =17.305, p < .001 for Model 2, both effective and inspiring teaching components), Professional knowledge and expectations (β = −.482) remained significantly affecting overall teaching quality perceptions. Inspiring teaching dimensions Flexibility and Teaching collaborative learning (β = .178) affected perceptions of overall teaching quality. Interestingly, more teaching flexibility was perceived negatively (β = −.251). Again, results indicated that the basic constant model was significant, suggesting other factors (such as subject differences may affect judgments of teaching quality.

5 Discussions

Overall the study results showed that effective teaching in the two instruments looked similar but differed much from inspiring teaching. The former indicates more innovative and require flexibility in application, while the latter may be more generic. Both correlation and clustering results indicated that teaching flexibility is associated with teaching students reflective thinking, and they may also be indispensable for innovative teaching and collaborative learning. Inspiring teachers may encourage students to reflect on their own and others’ views and engage them in collaborative learning activities. Thus, it seems that flexibility is a teaching asset not necessarily co-occurring as effective teaching practices.

Interestingly, correlations indicated that strong professional knowledge might hinder the adoption of innovative teaching and hamper teaching flexibility. Inspiring teaching may emerge in the early teaching stage when a teacher still has not shown exceptionally strong in his/her professional knowledge. Perhaps some professional development programs can support teachers with sound professional knowledge to adopt more innovative and flexible teaching. The following sessions address the limitations, significances, implications for professional development and conclusion.

5.1 Distinctions Between Effective and Inspiring Teaching

Empirical studies on the distinctions between effective and inspiring teaching are rare because we lack proper theoretical frameworks and associated instruments to distinguish them. Sammons and her colleagues (2014, 2016) contended that an important distinction between inspiring and effective teaching lies in our theory and methodology as well as our perspective of measurement and evaluation. Sammons et al. (2016) argued that theories without direct observation and measurement, but primarily on attitudinal measures, interviews, and similar indirect measures, are inadequate. Regarding teacher evaluation, as “the word ‘inspiring’ casts a wider net linking with affective and social-behavioural outcomes, [this] raises questions about the extent to which inspirational outcomes overlap with effective outcomes, and whether effectiveness is compatible with, part of, or different from inspiring practice” (Sammons et al., 2016, p. 125).

Similar to findings on English and Mathematics in Ko et al. (2019a, b), the cluster analysis supported a distinction of effective and inspiring teaching. However, only two of the teaching dimensions originally proposed as inspiring teaching in Ko et al. (2015), that is, Flexibility and Reflectiveness or Teaching reflective thinking. This raises the question that some aspects are basic or occur in a broader range of classrooms, while some are more context or subject-specific. Moreover, while Sammons et al. (2014, 2016) suggested that inspiring teachers were “dedicated, positive, and caring” teachers in their study, conceptually related factors like Enthusiasm for teaching,

Positive relationships with students, Safe classroom climate, and Positive classroom management were associated with other factors associated with effective teaching instead. We are not sure whether the different results might involve cultural influences. That is, effective teachers in Hong Kong samples were more dedicated, positive, and caring. Though it is hard to conceive that inspiring teachers do not have these characteristics, our current study cannot provide conclusive answers.

5.2 Innovative Teaching in Inspiring Teaching and Professional Development Implications

Our clustering results indicated that innovative teaching did not associate closer with inspiring teaching as one might expect. In the current conceptualisation, the factor Innovative Teaching concerns the extent to which ICT is applied in teaching and learning, which could be a narrow conception of innovativeness for other researchers. For example, Maass et al. (2019) consider that innovative teaching approaches also include those that can combine and scale-up material- and community-based implementation strategies. In OECD’s (2014) articulation, innovative teaching can concern regrouping educators and teachers for collaborative planning, orchestration and professional development, team teaching to target specific groups of learners, widening pedagogical repertories like inquiry learning, authentic learning, and mixes of pedagogies, while pedagogical possibilities in ‘technology-rich’ environment are just a few narrower options. This may imply that the current conceptualisation of innovative teaching is too restrictive to include teaching practices that can be connected to inspiring teaching.

Moreover, innovative teaching is still a weaker aspect in non-technology STEM subjects, perhaps in other academic subjects too. This is a little surprising that subjects that are traditionally conceptualised as STEM subjects like Mathematics and Science did not show stronger relationships with innovative teaching involving technology. As our sample was limited to lessons from a secondary school, our results are hardly conclusive. However, our results suggested that if creating technologically-rich learning environments for STEM subjects is a goal for innovative teaching, there are still much room for school improvement.

Inspiring teaching may emerge in the early stage of teaching when a teacher still has not shown exceptionally strong in his/her professional knowledge. Professional knowledge might hinder the adoption of innovative teaching and hamper teaching flexibility. Flexibility may be the key focus for future professional development because there is a dilemma for teachers in choosing flexibility in teaching and a better impression of teaching quality. We wish teachers to think out of the box, be flexible and be capable of reflective thinking and organise collaborative learning. Thus, we need to support them with achieving these goals without running into the risks of losing control in class.

5.3 Limitations

The project was small, with the number of lessons for analysis significantly reduced from the initial project plan of 300 lessons to 97 because of limited financial and human resources. Nevertheless, it was estimated that the current sample size would still be sufficient to perform the statistical analyses without sacrificing the benefit of comparing instruments developed for different purposes. This strategy was considered worthwhile and consistent with the research strategy on instrument comparison in the researcher’s previous projects. Our study is an initial step to define inspiring teaching and its outcomes, and we cannot claim that our results can resolve the problem of an overall lack of clarity and agreement completely.

5.4 Significance

These findings contribute to academic and professional communities in linking effective and inspiring teaching practices. The clustering results showed that teaching behaviours associated with inspiring teaching had a different pattern from effective teaching. The multiple regression results further indicated that inspiring teaching showed a distinct group of teaching practices differing from effective teaching and impacts student engagement and the judgement of overall teaching quality differently. The CETIT seems to be a reliable tool to support researchers to study inspiring teaching in more diverse contexts, particularly in subjects like mathematics, science, language arts, art and music, where inspirations to students are found significant.

The current findings are also readily comparable with the findings in previous video studies on TIMSS lessons (e.g., Stigler et al., 1999; Seidel & Prenzel, 2006; Janik & Seidel, 2009) and a video study by the OECD on the teaching practice in nine economies (OECD, 2020). Inspiring teaching practices at secondary schools are crucial indicators of a paradigm shift in secondary education (Cheng & Mok, 2008). They also show the extent of pedagogical innovation after major curriculum reforms are introduced (Lee, 2014). Finally, the newly developed instrument will help researchers study inspiring teaching in more diverse contexts, particularly in subjects like mathematics, science, language arts, art and music, where inspirations to students are found necessary.

6 Conclusion

This study confirmed that inspiring teaching has a different pattern from that of effective teaching. The comparisons between the CETIT and ICALT indicated that the two high-inference instruments were similar in theoretical conceptualisations, administration, and reliability. While the latter looks generic, the former has a broader spectrum of teaching practices and higher relevance for observing lessons and contexts where innovative teaching, reflective thinking, flexibility and student collaboration are expected. Thus, the CETIT may have the advantage of incorporating a component associated with the inspiring teaching characteristics if a researcher has to choose only one instrument for research.

References

Allen, J., Gregory, A., Mikami, A., Lun, J., Hamre, B., & Pianta, R. (2013). Observations of effective teacher-student interactions in secondary school classrooms: Predicting student achievement with the classroom assessment scoring system–Secondary. School Psychology Review, 42(1), 76–98.

Bacher-Hicks, A., Chin, M. J., Kane, T. J., & Staiger, D. O. (2019). An experimental evaluation of three teacher quality measures: Value-added, classroom observations, and student surveys. Economics of Education Review, 73, 101919.

Cantrell, S., Fullerton, J., Kane, T. J., & Staiger, D. O. (2008). National board certification and teacher effectiveness: Evidence from a random assignment experiment (No. w14608). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Casabianca, J. M., McCaffrey, D. F., Gitomer, D. H., Bell, C. A., Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2013). Effect of observation mode on measures of secondary mathematics teaching. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 73(5), 757–783.

Cheng, Y. C., & Mok, M. M. (2008). What effective classroom? Towards a paradigm shift. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 19(4), 365–385.

Creemers, B., & Kyriakides, L. (2008). The dynamics of educational effectiveness: A contribution to policy, practice and theory in contemporary schools. Routledge.

Day, C., Sammons, P., Kington, E., & Regan, E. K. (2008). Effective classroom practice (ECP): A mixed-method study of influences and outcomes. ESRC.

Ellett, C. D., & Teddlie, C. (2003). Teacher evaluation, teacher effectiveness and school effectiveness: Perspectives from the USA. Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, 17(1), 101–128.

Garrett, R., & Steinberg, M. P. (2015). Examining teacher effectiveness using classroom observation scores: Evidence from the randomisation of teachers to students. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(2), 224–242.

Gitomer, D., Bell, C., Qi, Y., McCaffrey, D., Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2014). The instructional challenge in improving teaching quality: Lessons from a classroom observation protocol. Teachers College Record, 116(6), 1–32.

Goe, L., Bell, C., & Little, O. (2008). Approaches to evaluating teacher effectiveness: A research synthesis. National Comprehensive Center for Teacher Quality.

Hafen, C. A., Hamre, B. K., Allen, J. P., Bell, C. A., Gitomer, D. H., & Pianta, R. C. (2015). Teaching through interactions in secondary school classrooms: Revisiting the factor structure and practical application of the classroom assessment scoring system–secondary. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 35(5–6), 651–668.

Harmin, M., & Toth, M. (2006). Inspiring active learning: A complete handbook for today’s teachers. ASCD.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta‐analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

Ingvarson, L., & Rowe, K. (2008). Conceptualising and evaluating teacher quality: Substantive and methodological issues. Australian Journal of Education, 52(1), 5–35.

Janik, T., & Seidel, T. (Eds.). (2009). The power of video studies in investigating teaching and learning in the classroom. Waxmann Publishing Co.

Kane, T. J. (2014). Do value-added estimates identify causal effects of teachers and schools? The Brown Center Chalkboard.

Kane, T. J., & Staiger, D. O. (2008). Estimating teacher impacts on student achievement: An experimental evaluation (No. w14607). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Kane, T. J., & Staiger, D. O. (2012). Gathering feedback for teaching: Combining high-quality observations with student surveys and achievement gains. Research Paper. MET Project. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Kane, T. J., Taylor, E. S., Tyler, J. H., & Wooten, A. L. (2011). Identifying effective classroom practices using student achievement data. Journal of Human Resources, 46(3), 587–613.

Kington, A., Sammons, P., Brown, E., Regan, E., Ko, J., & Buckler, S. (2014). Effective classroom practice. Open University Press.

Ko, J. Y. O. (2010). Consistency and variation in classroom practice: a mixed-method investigation based on case studies of four EFL teachers of a disadvantaged secondary school in Hong Kong. [Unpublished Doctoral Thesis]. The University of Nottingham.

Ko, J., & Sammons, P. (2013). Effective teaching: A review of research and evidence. CfBT Education Trust.

Ko, J., Chen, W., & Ho, M. (2015). Teacher effectiveness and goal orientation (School report No.1). Hong Kong Institute of Education.

Ko, J., Sammons, P., & Kyriakides, L. (2016). Developing instruments for studying inspiring teachers and their teaching practice in diverse contexts. Final report. The Education University of Hong Kong.

Ko, J., Fong, Y., & Xie, A. (2019a, August 6). Effective and inspiring teaching in math and science classrooms: Evidence from systematic classroom observation and implications on STEM education. WERA Annual Meeting in Tokyo, Japan.

Ko, J., Sammons, P., Maulana, R., Li, W., & Kyriakides, L. (2019b, April). Identifying inspiring versus effective teaching: how do they link and differ?. The 2019 Annual Meeting of American Educational Research Association (AERA).

Kyriakides, L., & Creemers, B. P. (2008). Using a multidimensional approach to measure the impact of classroom-level factors upon student achievement: A study testing the validity of the dynamic model. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 19(2), 183–205.

Lee, J. C. K. (2014). Curriculum reforms in Hong Kong: Historical and changing socio-political contexts. In C. Marsh, & J. C. K. Lee (Eds.), Asia’s high performing education systems (pp. 35–50). Routledge.

Li, T. (2015). Principals’ instructional leadership in the context of curriculum reform in China. [Unpublished Doctoral Thesis]. The Hong Kong Institute of Education.

Maass, K., Cobb, P., Krainer, K., & Potari, D. (2019). Different ways to implement innovative teaching approaches at scale. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 102(3), 303–318.

Maulana, R., Helms-Lorenz, M., Irnidayanti, Y., Chun, S., de Jager, T., Ko, J., & Shahzad, A. (2020, Jan). Effective teaching behaviour across countries: Does it change over time?. 33rd International Congress for School Effectiveness and Improvement, Marrakech, Morocco.

Muijs, D., & Reynolds, D. (2017). Effective teaching: Evidence and practice. Sage.

OECD. (2014). Measuring innovation in education: A new perspective. Educational research and innovation. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264215696-en

OECD. (2020). Global teaching InSights: A video study of teaching. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/20d6f36b-en

O’Leary, M. (2020). Classroom observation: A guide to the effective observation of teaching and learning. Routledge.

Opdenakker, M. C., & Van Damme, J. (2007). Do school context, student composition and school leadership affect school practice and outcomes in secondary education?. British Educational Research Journal, 33(2), 179–206.

Sammons, P., Thomas, S., & Mortimore, P. (1997). Forging links: Effective schools and effective departments. Sage.

Sammons, P., Kington, A., Lindorff-Vijayendran, A., & Ortega, L. (2014). Inspiring teachers: Perspectives and practices. CfBT Education Trust.

Sammons, P., Lindorff, A. M., Ortega, L., & Kington, A. (2016). Inspiring teaching: Learning from exemplary practitioners. Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 1(2), 124–144.

Schaffer, E. C., Nesselrodt, P. S., & Stringfield, S. (1994). The contributions of classroom observation to school effectiveness research. In D. Reynolds, B. Creemers, P. S. Nesselrodt, E. C., Shaffer, S., Stringfield, & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Advances in school effectiveness research and practice (pp. 133–150). Pergamon.

Schleicher, A. (2015). Schools for 21st-century learners: Strong leaders, confident teachers, innovative approaches. In International summit on the teaching profession. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/schools-for-21st-century-learners_9789264231191-en

Seidel, T., & Prenzel, M. (2006). Stability of teaching patterns in physics instruction: Findings from a video study. Learning and Instruction, 16(3), 228–240.

Stigler, J. W., Gonzales, P., Kwanaka, T., Knoll, S., & Serrano, A. (1999). The TIMSS videotape classroom study: Methods and findings from an exploratory research project on eighth-grade mathematics instruction in Germany, Japan, and the United States. NCES 99–074, U.S. Government Office.

Taber, K. S. (2017). Reflecting the nature of science in science education. In K. S. Taber & B. Akpan (Eds.), Science education (pp. 21–37). Sense Publishers.

Vieluf, S., Kaplan, D., Klieme, E., & Bayer, S. (2012). Profiles of teaching practices and insights into innovation: Results from TALIS 2008. OECD.

van de Grift, W. (2007). Quality of teaching in four European countries. Educational Research, 49, 127–152.

van de Grift, W. (2014). Measuring teaching quality in several European countries. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 25(3), 295–311.

van de Grift, W., Helms-Lorenz, M., & Maulana, R. (2014). Teaching skills of student teachers: Calibration of an evaluation instrument and its value in predicting student academic engagement. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 43, 150–159.

Walker, A., Hu, R., & Qian, H. (2012). Principal leadership in China: An initial review. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 23(4), 369–399.

Weisberg, D., Sexton, S., Mulhern, J., Keeling, D., Schunck, J., Palcisco, A., & Morgan, K. (2009). The widget effect: Our national failure to acknowledge and act on differences in teacher effectiveness (2nd ed.) New Teacher Project.

Yim, O., & Ramdeen, K. T. (2015). Hierarchical cluster analysis: Comparison of three linkage measures and application to psychological data. The Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 11(1), 8–21.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ko, J. (2023). Effective and Inspiring Teaching in STEM Classrooms: Evidence from Classroom Observations with Instrument Comparisons. In: Maulana, R., Helms-Lorenz, M., Klassen, R.M. (eds) Effective Teaching Around the World . Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31678-4_26

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31678-4_26

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-31677-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-31678-4

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)