Abstract

The objective of this study is to examine factors contributing to entrepreneurial intention, motivation and barriers among female university students. For this, we take a case study approach and focus on a Team Academy undergraduate degree programme run in Bristol, UK, which bases its pedagogical model on student-centred, experiential and team-based learning where students use their team companies through 3 years to engage in real-world, trade-based activities and ventures and reflect on their learning by getting support and encouragement from team coaches and mentors. Data gathered through semi-structured questionnaires from female students and graduates of the programme since it was launched in 2013–2014 shows that entrepreneurial motivation, intentions and perceptions on barriers might have specific characteristics for entrepreneurial females in higher education as the reasons and ambitions are also influenced by their student identity, beyond their entrepreneurial identity.

Our findings highlight that the experiential-led nature of the Team Academy educational setting provides a supportive environment which facilitates enhanced levels of self-efficacy for female entrepreneurial students, i.e. their belief in their ability to start ventures is enhanced through their practical experiences of doing so during their programme of study.

While female students are in the minority on the programme, making up just 15% of the cohort, their entrepreneurial intentions remain strong or increase during their time at university, and they have a positive attitude towards the benefits of becoming entrepreneurs. However, our data suggests that female students may lack the confidence to take actions and risks, and the support network of their peers and team coaches is key in empowering them and helping to minimise self-doubt.

The findings in this chapter inform changes within the programme and suggestions for future development of a more inclusive and diverse degree. The findings also have implications for entrepreneurship educators in further understanding the potential motivations, entrepreneurial intentions and entrepreneurial barriers of female students engaging in an entrepreneurial degree programme. This offers important considerations in terms of how inclusivity and diversity can be reflected in curriculum design.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The current academic debate surrounding female entrepreneurs focuses on barriers and gender differences. As GEM report suggests in the majority of economies, new businesses are more likely to be started by men than women (Bosma et al., 2021). The ratio of female to male early-stage entrepreneurship varies across the UK regions, so care needs to be taken using the often-repeated statement that “women are half as likely as men to be starting their own business in the UK”. The UK female to male TEA ratio of 63% in 2019 is higher than in previous years (Hart et al., 2020), yet white males continue to dominate the entrepreneurial landscape (Pages, 2005). In terms of their motivations to start a business, studies suggest that females in the UK tend to be more motivated by making a difference in the world or earning a living than by building wealth and income or continuing a family tradition (DeMartino & Barbato, 2003; Hart et al., 2020). This, together with reports of female entrepreneurs being hardest hit by the pandemic, has shaped the current UK policy debate leading to a government pledge of 600,000 new female-run businesses by 2030. While these factors are undoubtedly true, the current debate misses “’why”’ these females decide to be entrepreneurial by starting a journey of experiential learning in education.

This in context, the field of entrepreneurship education has been characterised by explosive growth given the importance of entrepreneurship in job and wealth creation (Koellinger & Roy Thurik, 2012; Lumpkin & Bacq, 2019). Not surprisingly, across the globe, entrepreneurship is taught to students at different levels and across many different disciplines (Jones & Iredale, 2010). Tiimiakatemia was developed in 1993 by Johannes Partanen at Jyväskylä University of Applied Sciences (JAMK) in Finland. Within entrepreneurship education, Team Academy (TA) is seen by some as an innovative pedagogical model that enhances social connectivity, as well as experiential (Kayes, 2002; Kolb, 1984), student-centred (Brandes & Ginnis, 1986) and team-based learning (Michaelsen et al., 2004). It also creates spaces for transformative learning to occur (Mezirow, 2006).

“If you really want to see the future of management education, you should see Team Academy”, Peter Senge (Senge, 2008) made this comment over a decade ago about TA, and since its inception, educators and practitioners engaging in TA-based programmes have continuously pushed at the innovation boundaries of more traditional teaching approaches to education (Urzelai & Vettraino, 2022a; Urzelai & Vettraino, 2022b; Vettraino & Urzelai, 2022a; Vettraino & Urzelai, 2022b). TA is often referred to as a model of entrepreneurship education (Sear & Norton, 2012) and the way it takes the learning through approach (Hytti & O’Gorman, 2004; QAA, 2018). TA is seen as the flagship programme for the University of the West of England (UWE) in terms of being enterprising, and UWE TA has been recognised as a first and leading example of the TA methodology in the UK, achieving, beyond others, the Collaborative Award for Teaching Excellence from Advance HE in 2021.

Today Team Academy-inspired degree programmes exist within higher education institutions spanning four continents and many countries (Urzelai & Vettraino, 2022a; Urzelai & Vettraino, 2022b; Vettraino & Urzelai, 2022a; Vettraino & Urzelai, 2022b). On Team Academy programmes, learners create and operate real enterprises, and their learning is centred around their team company, a team of up to 20 fellow students that collaborate on projects and ventures and support each other’s learning goals (Davies et al., 2022). Each team company is assigned a team coach, who supports learning through enquiry rather than instruction, and students are referred to as “team entrepreneurs” to emphasise the practice-led nature of the programme and to espouse the value of entrepreneurial mindset. Learners are required to engage in self-managed learning with support from others, namely, peers within their team company and their team coach. This involves a form of negotiated learning in which they are required to develop learning goals that align to their personal ambitions as well as the mission, vision and values of their team company, with regular feedback provided by their team coach and their peers.

However, “essential and interdependent” support functions that need to be in place for students making the transition into university education include not only cognitive support through course materials and resources or systems support from the institution but also affective support by creating a nurturing and supportive environment (Tait, 2000). You might expect that the team- and coaching-based experiential learning pedagogy adopted within TA would accommodate these functions, but the fact is that although females perform well and have higher pass rates and higher marks in the UWE TA programme, the number of females enrolled is much lower than in other business and management programmes. Since 2013, 364 students have joined the programme at UWE, out of which only 58 were females (15%). An average of 17% females enrol onto the UWE TA programme each year, compared to 42% for business management programmes since 2017. These are the future female leaders and entrepreneurs of the UK (Urzelai, 2021).

Therefore, this project aims to explore the intentions and motivations that young females have to become team entrepreneurs within a Team Academy setting and the barriers they face in their entrepreneurial journey.

The chapter will follow the following structure. We will first introduce the literature review on intentions, motivation and barriers that female entrepreneurs face. We then explain our methodology. After that we present our findings and analysis. The chapter ends with some general observations and conclusions.

2 Literature Review

Our chapter intends to better understand female entrepreneurship students in higher education, so for that purpose, we will focus our literature review in understanding female entrepreneurial intentions, female entrepreneurial motivations and the barriers and limitations that female entrepreneurs may face.

2.1 Entrepreneurial Intentions

In recent years entrepreneurship intention research has encompassed a wide range of topics including the impact of self-efficacy, entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial role models. Scholars have argued that entrepreneurship does not happen serendipitously and comprises of a set of skills that can be learned (Bazan et al., 2019). Entrepreneurship education has thus received a lot of attention in relation to its influence on entrepreneurial behaviours and intentions (Bae et al., 2014; Opoku-Antwi et al., 2012). There is further evidence of the role of entrepreneurship education in improving levels of self-efficacy, which seems to be intrinsically linked to entrepreneurial intentions.

Researchers have examined the relationship between entrepreneurial intentions and entrepreneurial self-efficacy and found that gender had a strong effect on both, with males demonstrating higher levels than females (Wilson et al., 2009). Furthermore, it was found that, when viewed separately, gender and education did not have a significant effect on entrepreneurial behaviour, but when viewed together, they did. Furthermore, when factoring in self-efficacy, it was found that its effects overwhelmed the others. These relationships seem to demonstrate the important role that entrepreneurship education can play in increasing self-efficacy, especially in females (Palmer et al., 2015).

A previous study has examined the impact of gender orientation on entrepreneurial intentions (EI) among university students (Palmer et al., 2015). Having studied an entrepreneurship course was a significant predictor of EI for females but not for males (Palmer et al., 2015). The authors suggest that entrepreneurship education may have contributed more to entrepreneurial self-efficacy in females than for males, particularly in the cases where females had fewer vicarious entrepreneurial experiences than their male counterparts. Knowing an entrepreneur was a significant predictor of male EI but was unrelated to levels of female EI. This finding seems to support the need for female role models in entrepreneurial contexts (Palmer et al., 2015).

Exposure to entrepreneurial role models and self-efficacy as a predictor of women’s entrepreneurial intentions (EI) has also been explored (Austin & Nauta, 2016). In a study of 620 female college students in the US, higher levels of self-efficacy and a larger number of entrepreneurial role models within one’s network were associated with higher levels of EI. The intensity of interactions with role models was also associated with higher levels of EI (Bae et al., 2014), thus emphasising the importance of meaningful connections with entrepreneurial role models for female nascent entrepreneurs.

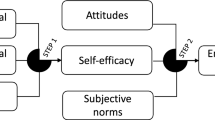

Entrepreneurial intention can be further understood by considering the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991), which suggests that personal attitude (a favourable or unfavourable evaluation of behaviour), subjective norms (perceived social pressure to perform or not perform a behaviour) and perceived behavioural control (perceived ease or difficulty of performing the behaviour) are antecedents of entrepreneurial intention.

2.2 Entrepreneurial Motivations

Entrepreneurs need to have confidence in the future and their abilities to start a business, but it is also sensible to assume that the COVID-19 pandemic might have had an impact in the start-up’s motivations. Some authors define four categories of entrepreneurs’ motivations (Sulikashvili et al., 2021):

-

1.

Intrinsic motivations: when the individual entrepreneur carries out their activity for the satisfaction it provides in itself, and not for any consequence that results from it. The commitment is spontaneous, fuelled by the interest, curiosity or challenge and the activity of creating.

-

2.

Extrinsic or instrumental motivations: any commitment in an activity with the aim of achieving any result associated with it. Motivating activity is only a means, or an instrument, to achieve something else. Obtaining a reward and avoiding a sanction are the most common examples. It is not the activity that motivates the individual but the prospect of a reward or the fear of a sanction.

-

3.

The need for independence and autonomy: the individual creates their company to be free from all external constraints, to be independent and to have full control of their life at work. The individual is at the origin of their own actions.

-

4.

Safety and well-being of the family: a significant contribution to the well-being of the entrepreneur, their family, their community or the territory.

Women are more motivated by autonomy, achievement, a desire for job satisfaction and other non-economic rewards, but the desire to make money is not, however, an unimportant motive (Cromie, 1987). So, they are usually more motivated by intrinsic factors.

In the context of the UK, studies found that building wealth was the stronger motivation, while continuing family tradition was ranked the weakest motivation, but females tend to evaluate both factors much lower than males and are more interested in what, for them, makes a difference in the world or to earn a living (Hart et al., 2020). Women are less competitively inclined than men in almost all countries included in the sample and are also less willing to take risks (Bönte & Piegeler, 2013). More detailed work found that having freedom, greater flexibility, challenging oneself and fulfilling a personal vision were the most popular motivations for females in the UK (Hart et al., 2017). Males tend to place economic gain as the primary motivation for starting a business, whereas females oftentimes go into business for themselves in order to achieve a more favourable family-work-life balance (DeMartino & Barbato, 2003).

However, it is important to note that although there is a strong gender effect on some motivational factors, gender itself needs to be examined along with other social factors to understand differences in motivations (Humbert & Drew, 2010).

2.3 Barriers and Limitations

This research has analysed entrepreneurial barriers that female entrepreneurship students faced before and during their start-up process. These were classified as “societal barriers”, “infrastructural barriers” and “behavioural barriers”. Our research recognises the extrinsic nature of these barriers and the interconnectivity they rely upon.

2.3.1 Societal Barriers

Gender stereotyping confines women to have qualities that are less likely to be associated with entrepreneurship (Hentschel et al., 2019). Accordingly, self-stereotyping by FEs may negatively influence their intentions to enter this field (Gupta et al., 2009). By “thinking entrepreneurship – thinking male”, it becomes apparent that the defining characteristics of the stereotypical entrepreneur are effectively those which define masculinity (Marlow, 2004). Implementing a broader view of stereotypes that considers congruence to gender identification deconstructs this stereotyping (Gupta et al., 2009).

Besides, much of the literature on entrepreneurship argues that sociocultural factors such as fear of failure, perceived opportunities or role models are the most important drivers of entrepreneurial behaviour (Arenius & Minniti, 2005), especially in the case of female entrepreneurship (BarNir et al., 2011).

2.3.2 Infrastructural Barriers

Gender-based discrimination causes women to experience barriers to acquiring financial capital in the form of loans, as measures used to determine creditworthiness have been based on masculinised norms such as domestic circumstances (De Andrés et al., 2021).

There is a lack of women in entrepreneurship, and this, therefore, affects social capital and access to resources. Female business networks are sparse and are found to either be too competitive or male-oriented (McGowan et al., 2015). Thus, there is a lack of sufficient and beneficial mentoring for females. This is compounded by the notion that a young woman cannot be successful both entrepreneurially and domestically simultaneously (Sandberg, 2013).

As a result, there is a perceived irrelevancy of female entrepreneurship as an option within the educational system – perceiving entrepreneurial endeavours as inappropriate for young women, thus stopping the self-confidence necessary for the development of an entrepreneurial career. However, the further women progress through the system, the more likely they are to possess entrepreneurial skills (McGowan et al., 2015). Thus, there is a need for an education system that encourages the development of business skills from the outset of education, to encourage the development of aspiring females from all educational backgrounds (Jones, 2014).

2.3.3 Behavioural Barriers

Aspiring females are likely to have lower levels of self-efficacy. They are often dismissive of entrepreneurship as a viable career choice and will choose a different career path if they believe they have a stronger skillset elsewhere (Wilson et al., 2007). This causes them to develop a risk aversion and are less likely to take risky entrepreneurial decisions. However, it has recently been suggested that the risk-taking propensity of women actually exceeds that of men, as by knowing the barriers they may face but still engaging with entrepreneurship, this exhibits a higher willingness to take risks than male counterparts (Castillo et al., 2017).

Furthermore, current coaching models are homogenous and fail to differentiate between gender. Many suggest that an impartial online coaching model would increase entrepreneurial self-efficacy by removing geographical barriers and offering increased flexibility (Hunt et al., 2019).

3 Research Methodology and Sample

This research adopts a case study research strategy (Yin, 2009) and qualitative approach (Saunders et al., 2015) as it attempts to gain a deep understanding of the whys and hows of a phenomenon in that particular context (TA programme).

Two of the authors of this chapter work in the programme as team coaches and had access to most of the students and graduates. A semi-structured questionnaire was distributed to all of the 60 female students and graduates of the programme, resulting in completion by 20 participants in total (33% of the total of females enrolled in the programme since it was launched in 2013–2014). It included both open (i.e. “what are your entrepreneurial motivations linked to the ‘need for independence and autonomy’?” The individual creates their company in order to be free from all external constraints, to be independent and to have full control of their life at work. The individual is at the origin of his own actions) and closed questions (i.e. if self-employed, how did you start in the business? (1) Entrepreneur by creation: I started a business from scratch. (2) Entrepreneur by acquisition: I started by buying an existing business. (3) Entrepreneur by inheritance: I continued a family business. (4) Franchise: I helped expand the franchisers’ business. (5) Other).

Fifty-five per cent of the responses we obtained were from current students who started after 2019 (see Table 1). Only 5% of the respondents had postgraduate or master’s degree, which means that most of the graduates did not continue education after graduation.

Most of the respondents (75%) were under 25 (see Table 2). The managerial experience is low as 55% have no experience and 45% have 1–5 years of experience.

Twenty-five per cent of the respondents were studying either full- or part-time. Thirty per cent were solely working full time as paid employees and 10% as self-employed. However, there is another 15% that although they are self-employed, they are also either studying or working as paid employees or both.

All the self-employed participants consider they are entrepreneurs by creation and not by acquisition/inheritance or through a franchise. The majority (80%) has been running their business for 1 to 5 years. In terms of employees, 40% have no employees and 60% have 1–4 employees in their business.

In terms of the sector of activity, the number of participants that are working (paid or self-employed) in services is quite high, accounting for 54% of the total, followed by 15% in retail.

A thematic analysis was adopted as a framework to analyse the data. The main concepts that emerged were identified and categorised into common themes by different researchers. Statements and quotes allocated to the themes were then used to present a textural description of the qualitative empirical data. A descriptive analysis was used to analyse the answers that were of a more quantitative nature.

4 Findings

4.1 Entrepreneurial Intentions

To analyse levels of entrepreneurial intentions, the survey asked respondents to indicate levels of agreement with the following statements, using a seven-point Likert scale:

-

I am ready to do anything to be an entrepreneur.

-

My professional goal is to become an entrepreneur.

-

I will make every effort to start and run my own firm/venture.

-

I am determined to create a firm/venture in the future.

-

I have very seriously thought of starting a firm/venture.

-

I have the firm intention to start a firm/venture someday.

Overall, each of the statements elicited a higher percentage of responses in agreement than disagreement, suggesting strong levels of entrepreneurial intentions among respondents. The statements which elicited the strongest levels of agreement overall were “My professional goal is to become an entrepreneur” and “I am determined to create a firm/venture in the future”.

The survey also explored whether entrepreneurial intention had changed during the student’s time on the programme. The data highlighted that 80% of respondents had the desire to start their own business before joining the team entrepreneurship programme. This intention changed during the programme for 65% of respondents. For a relatively small proportion of respondents (15%), their intention has moved away from entrepreneurship, or this has become a longer-term ambition for the future with their shorter-term goals focused on gaining employment. However, a larger majority (40%) highlight that their entrepreneurial intentions have strengthened during the programme or their perception of entrepreneurship has shifted to a more obtainable and realistic goal through increased self-efficacy and through gaining relevant experience. This is encapsulated in the following quotes:

I always use to dream about having my own business but never thought about actually setting one up. I thought I would be better working for someone in a large company. However, after joining the TE program I realized that I’m more than capable of setting up my own business and have now realized that having my own business is all I want. (R5)

I would say the desire got stronger. It was more of a dream before I started TE but the programme helped me to see it as more of a reality and take the steps to make it happen. (R16)

It is interesting to note that both respondents use the word “dream”, suggesting that entrepreneurship was previously viewed as unobtainable or unrealistic. This supports previous findings (Palmer et al., 2015) in relation to entrepreneurship education increasing levels of self-efficacy in females through providing knowledge and experience, and thus confidence, in the process of becoming an entrepreneur.

Figure 1 indicates the numerical data in relation to participants’ attitudes towards entrepreneurship. A series of statements were derived based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) model (Ajzen, 1991), and respondents were asked to rank each of the statements from 1 to 7, where 1 indicates total disagreement and 7 indicates total agreement.

A mean score of 6.1 indicates that the majority of respondents hold a positive personal valuation of being an entrepreneur, thus further suggesting strong levels of entrepreneurial intention among participants. This goes in line with studies that found a positive and significant influence of personal attitude and perceived behavioural control on entrepreneurial intention in females (Dinc & Budic, 2016). Respondents are, on average, more neutral in relation to the subjective norm, i.e. feeling social pressure to carry out entrepreneurial behaviours, and they have a higher disparity of opinions on this dimension. This supports previous findings (Palmer et al., 2015) where knowing an entrepreneur was a significant predictor of EI for males but not for females, perhaps owing to a lack of female entrepreneurial role models. Participants are also somewhat neutral overall in relation to the perceived behavioural control, suggesting that while participants may hold a positive attitude towards the benefits of becoming an entrepreneur, they are less confident in their abilities to do so. This is in line with previous studies highlighting lower levels of entrepreneurial self-efficacy in females (Wilson et al., 2009).

4.2 Entrepreneurial Motivations

Many respondents emphasised the practical element of the course as a driver to join the programme and how the methodology was seen as more appropriate for people with different learning styles. This reflects that the TA methodology could be much more inclusive as students are able to personalise their learning to surpass some of the barriers found in traditional academic settings under teacher-led approaches.

I liked the practical element. I would always lose attention if talked at for too long. I find even if I tried really hard in academics I still would never get the desired results but it was more achievable with TE. I also always dreamed of owning a cafe so I thought entrepreneurship would be a good way of doing that. (R16)

I thought it would be a good opportunity to gain real life skills that I could take with me when hopefully starting my own business. (R18)

I joined the program because traditional degrees didn’t suit my learning style. I get bored and distracted very easily but found this course to be the perfect fit as it was practical and pushed me out of my comfort zone. (R5)

I wanted more control over my future, I loved working with people, leading and learning about business. Entrepreneurship brought my love for these together and offered the freedom for me to make it my own. (R14)

Many mentioned within their main three reasons the networking and team element of it. This goes in line with studies that argue that social capital is emphasised for women, who may disproportionately require it in order to become entrepreneurs (Humbert & Drew, 2010).

I can work with others and lead in a safe environment. (R14)

To work closely with a range of different people and make friends for life. (R6)

The motivations that the participants have to start a business were measured with a scale of importance level from not important at all (Ajzen, 1991) to very important (BarNir et al., 2011) (see Table 3).

The motivation was mainly related to having freedom and flexibility, having to challenge themselves and desiring to fulfil a personal vision. The least important factors were to continue a family tradition or to follow the example of a person they admire. Wealth and income related motivations were of moderate importance.

Although the results are in line with other results in terms of the factors that are the most important among that list (Hart et al., 2017), if we compare the data with the results of that UK level GEM report, the percentage of female entrepreneurs stating the motivation was fairly or very important varies. In our context (HE) “to follow the example of a person I admire” was rated much lower (20% vs 38.5%), while others were stronger motivations for our young female team entrepreneurs, such as “fulfilling a personal vision” (100% vs 84.2%), “challenge” (95% vs 83.5%), “income” (80% vs 69.2%) and “building wealth” (80% vs 69.6%).

When talking about intrinsic motivations (Table 4), the participants talk a lot about autonomy, freedom and achievement or being satisfied and enjoying what they do. Although money is one of the extrinsic motivations that was more frequently repeated among the responses obtained, there were other factors that represent how the female entrepreneurs need to find “external validation” to what they do.

Participants referred to the need for independence and autonomy as an important motivator for them which they linked to running a team, having the freedom to learn and create or being in control of the decision-making process.

I am motivated by my own creativity and to not have limited boundaries when it comes to creativity. I want to work for myself and not feel limited in my ability to achieve more than what my manager/employer would want me to achieve. I look forward to running my own business when I work freely and independently, working with my own timetable. (R5)

I love having freedom in what I want to learn and develop. (R19)

Not having to answer to anyone or follow another leaders’ rules or regulations. If I had my own business I would create them myself. (R12)

It’s about having more control. As an entrepreneur you can have a meaningful say it what happens and how things are run, it enables you to create your reality. (R16)

The idea of a money-free lifestyle, whereby I can live a lifestyle and not have to consider cost, is really appealing. Coming from a working-class background, I have always wanted to succeed within a career to the point that I don’t have to think about what I am spending. In addition, I have always been very driven to make this life for myself rather than be given such lifestyle. (R3)

In terms of the motivations related to the safety and well-being of the family, this was less relevant in our context as not many female entrepreneur students had family responsibilities. However, the participants acknowledged being able to contribute to the well-being of their families as an important aspiration. They look at it from the perspective of having more time for family but also from a financial point of view:

Being able to take care of my family is a motivator to be successful. (R14)

I want to be able to see my family when I need/would like to. I would like to be able to socialize with friends and family without feeling unable to due to work commitments. I want to be able to support them where I can. I feel mentally happy when I am working on my own projects/goals and aspirations compared to those that have been set for me. Therefore, being an entrepreneur will make me more physically happy compared to an everyday job. (R5)

Success often results in money. I have always to give back to those that have put so much time and effort into helping me build my entrepreneurial career within these early days and succeeding within my career is a way of doing that. Similarly, coming from a working-class background I didn’t go hungry but, money was often tight when I was little. Personally, being able to ensure my children have the financial security they need to build their desired futures is really important and another reason behind why I want every venture I build to succeed. (R3)

5 Barriers Towards Entrepreneurship

When creating our survey, the aim was to examine the different types of barriers as established through prior literature. We asked participants to rank a number of barriers from 1 (to an extremely small extent) to 7 (to an extremely large extent). By doing this, we could analyse which of the barriers most female TAs perceive to be the strongest. We also compared perceived barriers before engaging in entrepreneurship, while doing so, in order to see if these barriers change (see Fig. 2).

The respondents identified a low level of legal and economic knowledge, lack of self-confidence, fear of failure, lack of work-life balance, lack of self-efficacy or limited access to finance as some of the main barriers.

It is interesting to note that most of those barriers are perceived as less of a limitation once the business is already running but that some of them increase: lack of self-confidence, lack of mentoring, lack of ambition for success, their personal attitude towards risk-taking, cultural barriers or fear of failure. Looking at standard variation values, there is a much higher disparity of opinions when evaluating the barriers during operations than when evaluating the barriers before setting up a business.

It seems that our participants perceive more behavioural barriers than infrastructural or societal barriers, so factors such as self-confidence, ambition for success, fear of failure or attitude towards risk-taking are more problematic for them (Table 5).

5.1 Societal Barriers

In terms of societal barriers, the results were divided. Very few of our participants found “gender stereotyping” to be a large barrier, with 50% rating this as a small barrier. We found the same result when looking at “male domination” and “discrimination” in the entrepreneurial sector. This implies that the notion of gender-based stereotypes acting as a barrier to female intentions of engaging with entrepreneurship is beginning to become outdated as we move towards a more gender-fluid society.

One barrier our participants did find to be large was a “lack of work-life balance”. Despite the rise in more gender-neutral concepts, the gendered division of labour is still unequal, and 75% of our participants found this to at least be a “moderate” barrier to success. There is a common notion that females are “not taken seriously as entrepreneurs”. This is the case for working mothers and people perceiving they have been patronised, which implies there is a need for coherent educational networks that target/adapt to working mothers, for instance.

5.2 Infrastructural Barriers

Limited access to financial support was found by our participants to be one of the main barriers to entrepreneurship, although this lessened once they started running their own business. This suggests that increasing economic intelligence through a TA programme is key to lessening assumed financial constraints.

Our participants, all of whom are degree educated, did not perceive a difference in educational level as a significant barrier, with over 50% of participants rating this barrier as a small extent. This correlates with the suggestion that the further women progress through the system, the more likely they are to possess entrepreneurial skills.

5.3 Behavioural Barriers

Low self-efficacy is highly cited in literature as one of the main barriers females face. Conversely, our results on this were mixed, with a 50/50 split between participants. Research undertaken within the same TA programme suggests that personal growth and confidence building are the key values that the programme reinforces (Davies et al., 2022), but there is a constant dilemma on how to offer the right balance between the team and individual dimensions or the business vs. competency outcomes (Urzelai & Davies, 2022). However, lack of self-confidence was found to be a large barrier. This may suggest that low entrepreneurial self-efficacy is translating in this form and that female entrepreneurs believe that they can succeed as entrepreneurs but lack the confidence to do so.

This lack of self-efficacy can also take the form of risk aversion. Where a behaviour is seen as entrepreneurially risky, females are less likely to engage in this behaviour than their male counterparts, which is also reflected in our results. This is not to suggest that women lack “ambition for success”, as when asked this the response from our participants overwhelmingly pointed towards this being a small barrier. It does however suggest that they have a lower risk-taking propensity and are less likely to make risky decisions that may, ultimately, benefit their business.

6 Conclusion

Despite the evidence of an escalation in entrepreneurial activity by women, females are still only half as likely as men to start a business, and education has a big role to play here. Inclusivity needs to be represented not only in the participants in the rooms but also in the teaching materials and resources, coaches and mentors or workshops and speakers. It is essential for an economy to welcome female entrepreneurs to start their own businesses, thus to create jobs, innovate and generate income.

Understanding the motives, intentions and barriers that our female entrepreneurs face in the context of an innovative entrepreneurial programme within HE is important to evaluate whether what we offer as educators supports their needs and aspirations. Societal barriers enshrined through centuries of patriarchal society have led to infrastructural barriers that act as an administrative hurdle. However, education can play a very important role in minimising the female entrepreneurs’ cognitive barriers that influence their behaviour.

The research findings show that the educational setting provides the supportive environment for them to gain confidence and the female entrepreneurial students gain self-efficacy through the experience of running their projects throughout their programme. They value the community and experiential learning approach and the freedom they get to personalise their learning and build their social capital. Throughout the degree they actually start believing that it is possible for them to start a business and they are capable of doing it.

Even if they are surrounded by males in the programme (only 15% are females) and some have not started their own business yet, their entrepreneurial intentions remain strong or increased during their time at university, and they have a positive attitude towards the benefits of becoming entrepreneurs, but they lack the confidence to take actions and risks, and they need their teams, coaches and surrounding to reinforce their achievements and past successes and provide constant feedback that minimises their own self-doubting feelings.

Besides, the programme might need to evaluate how the message is received externally as entrepreneurship has connotations that might stop females from taking that career route. The message could focus not just on “venture creation” or “business outcomes” but on providing the support system for females to develop entrepreneurial and enterprising skills and competencies that make them flourish into more independent and confident living and thinking individuals. However, this poses a debate to the programme team as both the data from females (10% are self-employed as their main source of income) and data from graduates (15%) show that the programme might support the students in their personal development ambitions regardless if those are venture creation related or not. Is this programme for entrepreneurial individuals that want to set up businesses and lead their own organisations? Or is it for enterprising individuals that develop self-confidence, curiosity and problem-solving skills and might want to work for other organisations? Hopefully the second will lead into the first, and enterprising skills will encourage entrepreneurial action and job creation.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Arenius, P., & Minniti, M. (2005). Perceptual variables and nascent entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 233–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-005-1984-x

Austin, M., & Nauta, M. (2016). Entrepreneurial role-model exposure, self-efficacy, and Women’s entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Career Development, 43(3), 260–272.

Bae, T. J., Qian, S. S., Miao, C., & Fiet, J. O. (2014). The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: A meta-analytic review. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(2), 217–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12095

BarNir, A., Watson, W. E., & Hutchins, H. M. (2011). Mediation and moderated mediation in the relationship among role models, self-efficacy, entrepreneurial career intention, and gender. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41(2), 270–297. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00713.x

Bazan, C., Datta, A., Gaultois, H., Shaikh, A., Gillespie, K., & Jones, J. (2019). Effect of the university in the entrepreneurial intention of female students. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Knowledge, 7(2), 73–97. http://dspace.vsp.cz/handle/ijek/115

Bönte, W., & Piegeler, M. (2013). Gender gap in latent and nascent entrepreneurship: Driven by competitiveness. Small Business Economics, 41(4), 961–987. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-012-9459-3

Bosma, N., Hills, S., Ionescu-Somers, A., Kelley, D., Guerrero, M., & Schott, T. ( 2021). Global entrepreneurship monitor (GEM) 2020–21 global report. : Babson College. Retrieved January 2022, from https://www.gemconsortium.org/file/open?fileId=50691

Brandes, D., & Ginnis, P. (1986). A guide to student centred learning. Blackwell.

Castillo, M., Dickinson, D. L., & Petrie, R. (2017). Sleepiness, choice consistency, and risk preferences. Theory and Decision, 82(1), 41–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-016-9559-7

Cromie, S. (1987). Motivations of aspiring male and female entrepreneurs. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 8(3), 251–261. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030080306

Davies, L., Urzelai, B., & Ozadowicz, K. (2022). Exploring the professional identity and career trajectories of undergraduates on a team-based, experiential degree programme. In G. J. Larios-Hernandez, A. N. Walmsley, & I. Lopez-Castro (Eds.), Theorising undergraduate entrepreneurship (Education: Pedagogy, digital teaching and scope) (pp. 191–210). Palgrave Macmillan.

De Andrés, P., Gimeno, R., & Mateos de Cabo, R. (2021). The gender gap in bank credit access. Journal of Corporate Finance, 71, 101782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2020.101782

DeMartino, R., & Barbato, R. (2003). Differences between women and men MBA entrepreneurs: Exploring family flexibility and wealth creation as career motivators. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(6), 815–832. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00003-X

Dinc, M. S., & Budic, S. (2016). The impact of personal attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioural control on entrepreneurial intentions of women. Eurasian Journal of Business and Economics, 9(17), 23–35. https://www.ejbe.org/index.php/EJBE/article/view/160

Gupta, V. K., Turban, D. B., Wasti, S. A., & Sikdar, A. (2009). The role of gender stereotypes in perceptions of entrepreneurs and intentions to become an entrepreneur. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(2), 397–417. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00296.x

Hart, M., Bonner, K., Prashar, N., Ri, A., Levie, J., & Mwaura, S. (2020). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor: United Kingdom 2019 Monitoring Report. Retrieved January 2020, from https://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/74711/1/Hart_etal_2020_Global_Entrepreneurship_Monitor_United_Kingdom_2019_Monitoring.pdf

Hart, M., Bonner, & Levie, J., (2017). Global entrepreneurship monitor (GEM): United Kingdom 2016 monitoring report. : Babson College. Retrieved September 15, 2018, from https://www.enterpriseresearch.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/GEM-UK-2016_final.pdf

Hentschel, T., Heilman, M. E., & Peus, C. V. (2019). The multiple dimensions of gender stereotypes: A current look at men’s and women’s characterizations of others and themselves. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00011

Humbert, A. L., & Drew, E. (2010). Gender, entrepreneurship and motivational factors in an Irish context. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 2(2), 173–196.

Hunt, C. M., Fielden, S., & Woolnough, H. M. (2019). The potential of online coaching to develop female entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 34(8), 685–701. https://doi.org/10.1108/17566261011051026

Hytti, U., & O’Gorman, C. (2004). What is ‘enterprise education? An analysis of the objectives and methods of enterprise education programmes in four European countries’. Education and Training, 46(1), 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910410518188

Jones, B., & Iredale, N. (2010). Enterprise education as pedagogy. Education+ Training, 52(1), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400911011017654

Jones, S. (2014). Gendered discourses of entrepreneurship in UK higher education: The fictive entrepreneur and the fictive student. International Small Business Journal, 32(3), 237–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242612453933

Kayes, D. C. (2002). Experiential learning and its critics: Preserving the role of experience in management learning and education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 1(2), 137–149. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2002.8509336

Koellinger, P. D., & Roy Thurik, A. (2012). Entrepreneurship and the business cycle. Review of Economics and Statistics, 94(4), 1143–1156. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00224

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice-Hall.

Lumpkin, G. T., & Bacq, S. (2019). Civic wealth creation: A new view of stakeholder engagement and societal impact. Academy of Management Perspectives, 33(4), 383–404. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2017.0060

Marlow, S. (2004). Accounting for change: Professional status, gender disadvantage and self-employment. Women in Management Review, 19(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/09649420410518395

McGowan, P., Cooper, S., Durkin, M. & O'kane, C ( 2015). The influence of social and human capital in developing young women as entrepreneurial business leaders. Journal of Small Business Management, 53 (3), p.645–661. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12176

Mezirow, J. (2006). An overview of transformative learning. In P. Sutherland & J. Crowther (Eds.), Lifelong learning: Concepts and contexts (pp. 24–38). Routledge.

Michaelsen, L. K., Knight, A. B., & Fink, L. D. (2004). Team-based learning: A transformative use of small groups in college teaching. Stylus.

Opoku-Antwi, G. L., Amofah, K., Koffuor, K., & Yakubu, A. (2012). Entrepreneurial intention among senior high school students in the Sunyani municipality. International Review of Management and Marketing, 2(4), 210–219. https://econjournals.com/index.php/irmm/article/view/250

Pages, E. R. (2005). The changing demography of entrepreneurship. Local Economy, 20(1), 93–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/0269094042000326670

Palmer, J., Griswold, M., Eidson, V., & Wiewel, P. (2015). Entrepreneurial intentions of male and female university students. International journal of business and public administration, 12(1) Retrieved from https://web.s.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=5&sid=6a2ba95f-5de1-4de4-9b34-5a9b548c9a90%40redis

QAA (2018) Enterprise and entrepreneurship education: guidance for UK higher education providers. Gloucester. QAA (The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education). Retrieved from www.qaa.ac.uk/docs/qaas/enhancement-and-development/enterprise-and-entrpreneurship-education-2018.pdf?sfvrsn=15f1f981_8

Sandberg, S. (2013). Lean. In women, work, and the will to lead. Random House.

Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (Eds.). (2015). Research methods for business students (6th ed.). Pearson Educational Limited.

Sear, L. & Norton, S. (2012). Essential frameworks for enhancing student success: Enterprise and entrepreneurship a guide to the advance HE framework for Enterprise and entrepreneurship education. Advance HE. Retrieved from https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/tags/leigh-sear

Senge, P. (2008). Peter Senge -team academy. Tiimiakatemia Global Ltd., Youtube channel. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kWENQJHp-U8

Sulikashvili, N., Kizaba, G., & Assaidi, A. (2021). Motivations and barriers of entrepreneurs in Moscow and the Moscow region. Business: Theory and Practice, 22(2), 256–266. https://doi.org/10.3846/btp.2021.13112

Tait, A. (2000). Planning student support for open and distance learning. Open Learning, 15(3), 287–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/713688410

Urzelai, B. (2021). Changemakers: Diversity and inclusivity in team entrepreneurship. Student partnership pedagogic project 2021–22 UWE. Internal report. Unpublished.

Urzelai, B., & Davies, L. (2022). Programme evolution, success factors and key challenges: The case of team entrepreneurship at UWE, Bristol. In B. Urzelai & E. Vettraino (Eds.), Team academy in practice (pp. 21–41). Routledge Focus on Team Academy.

Urzelai, B., & Vettraino, E. (2022a). Team academy in practice. Routledge Focus on Team Academy. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003163114

Urzelai, B., & Vettraino, E. (2022b). Team academy in diverse settings. Routledge Focus on Team Academy. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003163176

Vettraino, E., & Urzelai, B. (2022a). Team academy and entrepreneurship education. Routledge Focus on Team Academy. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003163091

Vettraino, E., & Urzelai, B. (2022b). Team academy: Leadership and teams. Routledge Focus on Team Academy. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003163121

Wilson, F., Kickul, J., & Marlino, D. (2007). Gender, entrepreneurial self–efficacy, and entrepreneurial career intentions: Implications for entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(3), 387–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2007.00179.x

Wilson, F., Kickul, J., Marlino, D., Barbosa, S. D., & Griffiths, M. D. (2009). An analysis of the role of gender and self-efficacy in developing female entrepreneurial interest and behavior. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 14(2), 105–119. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1084946709001247

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods. Thousand oaks, CA: Sage. The Canadian Journal of Action Research, 14(1), 69–71. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjpe.30.1.108

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Urzelai, B., Caple, L., Watkins, S. (2023). Female Entrepreneurs’ Motivations, Intentions and Barriers in Higher Education: A Case Study from Team Academy Bristol. In: Block, J.H., Halberstadt, J., Högsdal, N., Kuckertz, A., Neergaard, H. (eds) Progress in Entrepreneurship Education and Training. FGF Studies in Small Business and Entrepreneurship. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-28559-2_15

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-28559-2_15

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-28558-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-28559-2

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)