Abstract

Given the increasing migration inflows in Ecuador in recent years, both the ruling government and the opposition, as well as a part of the public opinion, have expressed concerns about the very presence of certain foreign residents, occasionally portraying them as the ‘antagonist’ by natives. Considering this context of rising anxiety for Ecuadorians over immigrants of certain nationalities, particularly Colombians, Cubans and Venezuelans, we focus in this chapter on emotions and the political psychology of the voter. This is to explore to what extent Ecuadorian voters’ emotional underpinning and anti-immigrant attitudes are associated with their populist and elitist attitudes. Using individual-level data and structural equation modelling to unpack the nexus between different negative emotions, attitudes and prospective electoral behaviour, our results report that populist attitudes significantly lead to higher immigrant attitudes and are also positively correlated to electorally supporting a populist radical left-wing candidate. Furthermore, having negative emotions – predominantly anger and distrust – towards some foreign residents increases the probability of depicting anti-immigrant attitudes and voting for populist choices.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

As a result of the voluminous migration outflow of Venezuelans throughout Latin America in recent years, public opinion in countries such as Ecuador has shifted to perceptions of ‘insecurity’, ‘a lack of jobs’ and ‘increasing anxiety’ over the very presence of immigrants. Being a country with a well-recorded emigration trajectory in the early 2000s, Ecuador has recently opted for a more restrictive policy toward inter-regional immigrants and a considerable fraction of the Ecuadorian electorate seems to concur with this policy backlash towards human mobility (Malo, 2021).

At the beginning of 2019, the then Ecuadorian Vice-President, Otto Sonnenholzner, declared that an apostilled criminal record would be requested from Venezuelan citizens entering the country, to ‘differentiate them from Venezuelans fleeing the government of Nicolás Maduro and others who take advantage of this situation to commit a crime’ (El Universo, 2019). Considering that Sonnenholzner’s statement is not the only one which suggests a Manichean opposition between ‘us’ (native or resident citizens) and ‘them’ (immigrants or residing foreigners) – reproducing, if not generating, a negative emotional underpinning in public opinion – we aim to explore the nexus between emotions on the one hand and anti-immigrant and populist attitudes on the other. The latter is activated by crises of all sorts; thus, we ask, to what extent are voters’ negative emotions and anti-immigrant attitudes prone to larger probabilities to support populist radical candidates in the upcoming election, and whether populist attitudes contribute to restrictive attitudes toward immigrants?

Although earlier literature has comprehensively addressed the link between populist attitudes and political behaviour (e.g. Akkerman et al., 2014; Müller, 2016; Schult et al., 2017; Van Hauwaert & Van Kessel, 2018), scholars overlook the relation between the electorate’s emotional base, their attitudes toward immigrantsFootnote 1 and populism. Exceptions have been successfully discussed in European cases (e.g. Mudde, 2017; Rico et al., 2017), where Islamophobia and overall anti-immigrant discourses have stirred a nativist-populist sentiment (see also the other chapters in this part of the book). Despite a visible turn to restrictive immigration policies in several Latin American countries (e.g. Acosta & Freier, 2015; Brumat et al., 2018; Finn & Umpierrez de Reguero, 2020), this nativist-populist sentiment is underestimated by public opinion assessments and can impact on electoral outcomes in the wake of the massive immigration of Venezuelans.

Understood as individual constructs that help us to perceive societal issues using a Manichean distinction – the ‘pure people’ versus the ‘corrupt elite’ – in which the people have unrestricted popular sovereignty (Mudde, 2004), populist attitudes may occasionally trigger anti-immigrant narratives. These attitudes can be conceptualised as latent variables and measured with a battery of items about subjective moods, beliefs, attitudes and positions toward immigrants (Hawkins et al., 2012).

This study draws on two surveys with non-probabilistic samples – one in 2019 (N = 1337) and the other in 2021 (N = 1289) – with individuals aged 16 and older in Ecuador. Despite our samples sharing several commonalities with the estimated population (INEC, 2019), they are non-generalisable given the nature of our fieldwork: online, promoted via Facebook Ads. Our scope is thus exploratory. Aiming to create a parsimonious model, we analyse the collected data using structural equation modelling (SEM), a method which enables us to incorporate both measurement analyses to work with latent variables and a structural assessment to address the correlations in our statistical model. As a complement, we also conduct a set of logistic regressions to correlate populist attitudes, emotions and prospective voting. By means of this methodological design, we expect to contribute to the open debates on populism studies in Latin America and focus on the nexus between negative emotional underpinning, populism and political behaviour – illustrating a salient context of anxiety over migration for the citizenry.

In what follows, we first briefly introduce the Ecuadorian migratory context. We then discuss populism, emotions and anti-immigrant attitudes, before outlining the data and method. Lastly, we present and discuss our results deriving from two SEMs and two logistic regressions.

2 The Ecuadorian Migratory Context

Traditionally, Ecuador has been a sending country, characterised by having negative migratory net rates. This phenomenon can be divided in two stages: before 1998, and the emigration that followed the banking crisis (Feriado Bancario) in 1999–2000 (Acosta et al., 2005). Alongside these two migratory waves, the country has experienced an increase in migration outflows since 2015 (Hurtado, 2018).

Yet, even if a third wave of emigration is rising, the exodus of Venezuelans has changed the label of Ecuador from a sending to a receiving country (Ramírez et al., 2019). Prior to the migration inflows of Venezuelans, Colombians fleeing the armed conflict started to increase (Hurtado, 2018). During the 1990s, around 125,000 foreigners immigrated to Ecuador. By the year 2003, 241,000 foreigners entered the country, mainly from Colombia, Cuba, Peru and the United States. Since then, many Colombians and Cubans have obtained refugee status, making Ecuador an influential example in Latin America for its refugee and asylum-seeker policies (Verney, 2009).

Different factors have motivated foreigners to move to Ecuador. Among them are the value of the US dollar vis-à-vis other Latin American currencies, the expansive provisions for migrants’ electoral rights and the active presence of refugee organisations in the country (Jara-Alba, 2017; Ramírez & Umpierrez de Reguero, 2019). On average, incoming migrants hold university-level degrees and reside in provinces near the borders of Colombia and Peru, as well as in Cuenca, Guayaquil and Quito – the most populated cities in Ecuador (Hurtado, 2018).

Prior to the peak of migration inflows in Ecuador, around 60% of Ecuadorians perceived that immigrants take over their jobs (Ramírez & Zepeda, 2015). In 2015, the Ecuadorian authorities deported 121 Cuban citizens in military aeroplanes to allegedly halt undocumented migration to the United States (Valdés, 2017). Over the last decade, the mass media have broadcasted that specific crimes have been ‘imported’ from Colombia (e.g., El Universo, 2004). Some Colombian and Peruvian immigrants have declared that the local police would not receive their complaints given their nationalities (El Correo, 2003). In recent years, discontent with the presence of non-citizen residents keeps rising (Cuevas, 2018; Malo, 2021; Ramírez et al., 2019). These informal and official narratives are full of stereotypes and threats (Malo, 2021), factors which have been influential in the decision of many Venezuelan immigrants to return to their origin country or relocate to other nations in Latin America (Ramírez et al., 2019).

In short, there is an ongoing debate on how to ‘integrate’ inter-regional immigrants in Ecuador. As the country has shifted from being a sending country to a receiving one, there is a growing discomfort for Ecuadorians about certain immigrant groups on the national territory (Ramírez & Zepeda, 2015), hence rendering the phenomenon and its possible implications relevant to our study.

3 Theory and Hypotheses

3.1 Populism and Elitism

In this chapter, we use the ideational approach to conceptualise populism and to formulate our hypotheses. Mudde defines populism as an ‘ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, “the pure people” versus “the corrupt elite” and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale of the people’ (2004, 543). This conceptualisation outlines three essential elements. First, populism is conceived as a ‘thin-centered’ ideology, requiring a ‘host’ ideology, such as nativism or socialism, to ‘politicize grievances that are relevant in their own context’ (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2018, 1670). Second, populism perceives politics as an opposition between good (‘the pure people’) and evil (‘the corrupt elites’) and can thus be qualified as Manichean (Hawkins & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2017); yet each political setting may have a unique set of the ‘people’ and the ‘elite’ (Canovan, 1999). Third, appealing to the general will is the method by which populism clusters a variety of different individual wills of common citizens, proclaiming popular sovereignty as the only source of political power (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2013).

To provide a clearer vision of populism, some scholars also conceptualise elitism and pluralism (Akkerman et al., 2014; Hawkins et al., 2012; Van Hauwaert & Van Kessel, 2018). Like populism, elitism also consists in a Manichean distinction, with ‘the elites’ conceived to be on the virtuous side, whereas ‘the people’ are on the corrupt one (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2013). Conversely, pluralism underlines the existence of diverse perspectives within a society. In addition, the ‘general will’ comprises a complex dynamic without fixed limits, instead of a monolithic general will, as conceived in populism (Ochoa Espejo, 2011).

Populist leaders tend to channel the people’s unsatisfied demands against a specific group of society (e.g. immigrants and corrupt elites). In populism studies, these groups correspond to the ‘antagonists’ (Laclau, 2005). Ideational scholars use this notion to claim that the oppositional stance of populist rhetoric has ‘the pure people’ on one side and the ‘corrupt elite’ on the other. Given the haziness within the discourse, to identify these two groups, populist radical right-wing parties hoist the ‘natives’ as a representation of the pure people and ‘immigrants’ as the antagonist (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2018). Although antagonists and the elite can discursively become separated groups, antagonism is usually represented by those who oppose the populist leader and ‘the people’. This distinction contraposes morality versus immorality, instead of establishing two specific groups opposing each other (Müller, 2016), allowing the antagonist to take different shapes – such as immigrants (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2018).

Considering this mechanism of both populism and elitism, we define populist and elitist attitudes as latent constructs containing an interrelated construct between the people, the elites and the general will (Hawkins et al., 2012). Even though empirical evidence worldwide suggests that populist and elitist attitudes can correlate with a wide array of radical and non-radical alternatives, we hypothesise that:

-

(H1a) the larger the populist attitudes that individuals display, the more likely it is that they intend to vote for populist radical left- and right-wing candidates, together with the expectation that

-

(H1b) elitist attitudes reduce the likelihood of electoral support for a populist radical left-wing candidate or PRLWC.

3.2 Negative Emotions and Anti-immigrant and Populist Attitudes

Emotions are a substantive part of politics. Correspondingly, the theory of reasoned motivation comprises three key elements to comprehensively understand them. First, all political stimuli have an emotional underpinning. Second, individuals are constantly evaluating their emotions vis-à-vis these stimuli. Third, the emotions of each individual will affect the way in which he or she perceives reality (Lodge & Taber, 2000), affecting different aspects of his/her decision-making processes, such as voting. Extensive research in the field of political psychology has proved that emotions do affect an individual’s political choices – for example, angry people could be more likely to support war or oppose liberal immigration policies (Vasilopoulos et al., 2018). Moreover, certain emotions may change individuals’ behaviour, even mobilising those who are reluctant to engage in political acts (Lamprianou & Ellinas, 2019).

More precisely, research has found that emotions, especially negative ones (e.g. distrust, anger and fear), play a relevant role in activating populist attitudes (Rico et al., 2017). Emotions also have a function when it comes to relation-building between collectives and candidates, as well as the creation of a sense of community among supporters (Schurr, 2013). Given the usage of a moral language employed in populist rhetoric, these leaders also appeal to the emotions of the electorate to polarise the political arena (Rovira Kaltwasser, 2014).

As negative emotions relate to populism, scholars have focused their studies on the search for the emotional roots of support for populist radical right-wing parties (Close & Van Haute, 2020; Salmela & von Scheve, 2017). Earlier literature reported that resentment is an essential aspect that might transform fear or powerlessness into anger against other groups labelled as ‘antagonists’ by a political leader (e.g. immigrants, unemployed people and the elite). Concerning the performance of negative emotions in populism, Rico and his colleagues (2017) assert that an individual’s anger generated as a response to a situation perceived as unfair could make him or her more likely to embrace populist attitudes. In this frame, we hypothesise that:

-

(H2) having negative emotions toward immigrants increases the odds of depicting anti-immigrant attitudes, along with the expectation that

-

(H3) individuals with higher levels of anti-immigrant attitudes will have a lower probability of voting for a PRLWC.

Negative emotions can be channelled against certain groups of individuals (e.g. immigrants and unemployed individuals), especially using populist rhetoric, in the wake of an antagonist, thus generating negative attitudes against them. Indeed, anti-immigrant attitudes can be present on the demand side of populism. This type of restrictive attitude tends to increase when the economic scenario seems positive and to decrease when there is an economic crisis (Rinken, 2015). This is because natives may believe that, apropos of the crisis, immigrants would return to their origin country. In other cases, countries whose citizens hold strong national identity may have higher levels of outgroup hostility towards immigrant groups (Hamidou-Schmidt & Mayer, 2020). Furthermore, perceiving a significant increase in the flow of specific immigrant groups can also fuel negative attitudes towards the phenomenon among natives (González-Paredes et al., 2022; Ramírez et al., 2019). Other studies have linked negative attitudes toward immigrants as a key element for supporting populist radical right-wing parties with a nativist component (Mudde, 2013; Rothmund et al., 2019).

Furthermore, there are theorists who have linked populist attitudes present in individuals with anti-immigrant attitudes. Hawkins and his colleagues (2020) argue that far-right populist attitudes can be ‘activated’ throughout anti-immigrant behaviour (e.g. Golden Dawn in Greece). Other contributions have shown that both populist left- and right-wing parties have performed better after mobilising concerns over immigration policies (Ivarsflaten, 2008). Additionally, Mudde (2017) establishes that populist radical right-wing parties need to activate the populist attitudes of their voters by appealing to anti-immigrant sentiments to capture their votes. Thus, we expect that:

-

(H4) higher levels of elitist and populist attitudes lead to higher anti-immigrant attitudes.

4 Data and Method

For our data collection, we launched two online surveys – one 2 weeks after the intense social mobilisations of October 2019 (N = 1337) and another just prior to the 2021 general elections (N = 1289) in Ecuador – with national coverage (including both rural and urban areas), promoted via Facebook Ads. Our unit of analysis was composed solely of Ecuadorian-born resident citizens aged 16 and older. We considered the age to vote in Ecuador (CNE, 2009) as a filter through which to survey the respondents.

Although it is well-known that researchers must consider that the Internet may compromise sample proportionality and representativeness when collecting data, coupled with ethical considerations associated with social networking platforms, Facebook has about 12 million users in Ecuador (Global Digital Report, 2019), a number that highly approximates the Ecuadorian electoral register of the 2017 presidential election (CNE, 2017), including the distribution between men and women. Consequently, we sought to keep similar standards of proportionality, heterogeneity and representativeness in the sample as compared to the population, when creating the online sample. In terms of the population, 49.9% of the voters were men and 50.1% women (CNE, 2017); of those who answered the survey, 51.9% were men and 48.1% women. Although there is a difference in these male–female ratios, they are not significant. Likewise, the number of Facebook users maintained a similar proportionality in the age and sex of those who answered the questionnaire, in relation to those registered to vote in 2017. Still, the pyramid of Facebook users has a notable variation in users between 16 and 19 years old. These are the largest group in the electoral register (CNE, 2017) and in the group of respondents. The modal data are between 20 and 23 years old – a plausible explanation for which may be the usage patterns of Facebook at these ages in Ecuador. Furthermore, the electoral register has voters in the age range 88–91 years as maximum values yet, among those who have an active account in the social network, it is only recorded as 65 years and older (Global Digital Report, 2019).

As we ran the data collection in 2019 after the wave of social mobilisations and 1 month prior to the 2021 general elections, this decision impacted on the quality of our data. Both events may have increased the (dis)interest and emotions around politics.

Our online fieldwork was successful, collecting about 2500 row responses. The attrition rate was no greater than 30%. We eliminated fewer than 3% of responses for not meeting the criteria for citizenship such as nationality or required age.

4.1 Estimation Strategies

As our baseline method, we analysed the collected data employing SEM, since this technique allowed us to measure latent and observable variables simultaneously (Hox & Berchger, 1998). SEM is useful for empirically testing theoretical constructs, as in the case of this chapter. This method adjusts to the nature of our variables. Previous contributions to the literature had already admitted that populist attitudes and anti-immigrant attitudes are effectively measured as latent variables (e.g. Akkerman et al., 2014; Hawkins et al., 2020; Meléndez & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2019; Rothmund et al., 2019). Yet, these pioneering studies failed to create a parsimonious model that comprises factor analyses in combination with regression analyses in the same statistical exercise. By creating a SEM, we methodologically contribute to the burgeoning literature on populist and anti-immigrant attitudes. Furthermore, we added two binary logistic regressions to unpack the nexus between different negative emotions, attitudes and prospective electoral behaviour.

4.2 Measures

The explanatory variables are populist and elitist attitudes, negative emotional underpinnings, attitudes toward immigrants and the intention to vote for populist candidates. As underscored, we measure populist and elitist attitudes following the ideational approach’s guidelines. Accordingly, we employed a tested scale of items to measure the electorate’s populist and elitist attitudes created by Hawkins and his colleagues (2012) and replicated by Akkerman et al. (2014). Assessing these items with a five-value Likert scale that oscillates from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5), we incorporate populist and elitist attitudes. For populist attitudes, most responses range from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘neither agree nor disagree’ (mean [μ] = 4.07; std. deviation [σ] = 0.93). Conversely, descriptive statistics for elitist attitudes report that most responses oscillate between ‘agree’ and ‘disagree’ (μ = 3.31; σ = 1.14).

We rely on the contribution of Rico and his colleagues (2017) to operationalise negative emotions – they asked their respondents to indicate the extent to which the economic crisis in Spain generated negative emotions such as sadness, fear, anxiety and anger. We adapted a similar rationale to the Ecuadorian context and asked: ‘Which of the following emotions (fear, distrust, hopelessness, anger, anxiety) best describes your perceptions in the wake of the presence of (1) Colombian, (2) Cuban, (3) Peruvian, (4) US and (5) Venezuelan nationals in Ecuador’. To clarify, we asked the same question for each immigrant group. These five groups of nationalities lead the ranking of immigrant residents in Ecuador as estimated in 2019. In particular, we inquire about Colombians, Cubans and Venezuelans, as there have been public episodes of xenophobia in Ecuador against them over the last two decades (El Correo, 2003; Ramírez et al., 2019; Valdés, 2017), as well as against Americans and Peruvians, given their demographic presence in both rural and urban areas in Ecuador. Bearing in mind this information, we coded this variable as ‘1’ – meaning the highest value in terms of negative emotions towards the five groups mentioned – and ‘0’ otherwise. Most common values fluctuate between 0.01 (no negative emotions) to 0.63 (negative emotions often towards specific groups such as Colombians and Venezuelans) (μ = 0.32; σ = 0.31).

Attitudes toward immigrants are a set of questions that may represent subjective perceptions of societal issues regarding immigrants, which is why we use the term anti-immigrant attitudes or restrictive/negative attitudes towards immigrants throughout this chapter. In our model, we discarded the items phrased in a positive way such as ‘Do immigrants improve Ecuadorian society by bringing new ideas and cultural attributes?’ Like the scale measuring populist attitudes, we utilised a Likert scale that ranges from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5) to assess anti-immigrant attitudes. Most answers fluctuate between strongly agree and neither agree nor disagree (μ = 3.88; σ = 0.93).

Like the pre-campaign national surveys in Ecuador, we asked respondents to what extent they intend to vote for pro-CorreaFootnote 2 and pro-Social-Christian Party (PSC) candidates. This four-value variable, which captures prospective electoral behaviour towards populist choices, ranged from ‘yes, definitely’ to ‘no, definitely’. Overall, most responses ranged between ‘yes, definitively’ and ‘no, probably’ for PRLWC (μ = 1.28; σ = 1.20) and ‘yes, probably’ to ‘no, definitively’ for a populist right-wing candidate (PRWC, μ = 1.18; σ = 1.09). We considered the adjective ‘pro-Correa candidate’ as a proxy for ‘PRLWC’ and the label ‘pro-PSC candidate’ as a proxy for ‘PRWC’. We excluded ‘radical’ in the latter coding as, in Ecuador, there are no populist radical right-wing parties yet. The most similar classification to that in the right axis is the PSC (González-Paredes et al., 2022).Footnote 3

Relying on cross-national survey items (e.g. Latinobarometer and World Values Survey), our first control is institutional trust. This variable can be a proxy of anti-establishment sentiments among the electorate. As anti-establishment is a prerequisite of populist identity (Meléndez & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2019), we expect that it inversely correlates with both anti-immigrant and populist attitudes. We also assess the institutional trust variable using a Likert scale. Overall, most responses ranged between ‘distrust’ and ‘trust’.

We also control our SEM by incorporating socio-demographic variables, particularly age, education, self-reported economic situation and religion. We coded age as a continuous variable. Our respondents fluctuate from 16 to 78 years old, with the average at 32 years. As in the Ecuadorian National Census of 2010, more than 50% of our respondents held a high-school degree, with a 30% on average who self-identified as professionals with a university degree. We measured self-reported economic status as an ordinal value in which respondents could choose between low-income and high-income statuses, with most responses oscillating between the two. Finally, we coded religion by using dummies of whether respondents self-identify as Protestant/Evangelical or as Catholic.

5 Findings

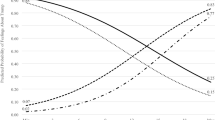

We now present and discuss the results of our data analysis. We constructed two SEMs to avoid multicollinearity and statistical saturation. The first comprises the intention to vote for a PRLWC, while the second replaces it for a PRWC. Both models display good fit indices. The standardised coefficients are depicted in Figs. 11.1 and 11.2 (see Table 11.1 in the appendix for more details). Since all variance inflation factors in both SEMs are fairly low (all <2), we report no multicollinearity prior to the interpretation of our findings.

SEM on populism, negative emotions, attitudes towards immigrants and intention to vote for a PRLWC

Note: N = 2494; CFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.05 (See Model 1 in Table 11.1). Coefficients are standardised estimates. p = * < 0.05, ** < 0.001, *** < 0.0001

SEM on populism, negative emotions, attitudes towards immigrants and intention to vote for a PRWC

Notes: N = 1288; CFI = 0.94; TLI = 0.93; RMSEA = 0.06 (See Model 2 in Table 11.1). Coefficients are standardised estimates. p = * < 0.05, ** < 0.001, *** < 0.0001

Figure 11.1 shows that populist attitudes are positively associated with anti-immigrant attitudes (ß [standardized] = 0.20, p < 0.001). Similarly, negative emotions among voters foster restrictive attitudes toward immigrants (ß = 0.62, p < 0.001). Maintaining all other variables constant, anti-immigrant attitudes are inversely correlated with PRLWC (ß = −0.10, p < 0.001). This is supported by the two significant relations observed between populist and elitist attitudes towards PRLWC. Unsurprisingly, the electorate’s populist attitudes fuel the likelihood of voting for a PRLWC (ß = 0.13, p < 0.001), while the larger the elitist attitudes which voters embrace, the lower the odds are that their electoral choice would be in favour of a PRLWC (ß = −0.09, p < 0.001). Finally, negative emotions are positively correlated with the intention to vote for a PRLWC (ß = 0.30, p < 0.001). In this model, we find no relation between elitist attitudes and anti-immigrant attitudes, as a direct effect.

Figure 11.2 illustrates similar significant relations compared to the previous model. Again, the larger the populist attitudes, the greater the restrictive attitudes toward immigrants (ß = 0.12, p < 0.05). Likewise, negative emotions boost anti-immigrant attitudes (ß = 0.78, p < 0.001). Changing the variable capturing prospective electoral behaviour, anti-immigrant attitudes do not seem to influence electoral support for a PRWC. Although the party that we chose to represent the PRWC (i.e. a pro-PSC candidate) has demonstrated clear-cut signs of populist rhetoric, its electorate tends to be pro-elite (ß = 0.26, p < 0.001) and anti-populist (ß = −0.14, p < 0.001). Moreover, negative emotions are directly associated with the intention to vote for a PRWC (ß = 0.25, p < 0.01). In this model, we find no relation between elitist attitudes and anti-immigrant attitudes, as well as the intention to vote for a PRWC and restrictive attitudes toward immigrants.

Unpacking the nexus between negative emotions and intention to vote for populist choices, we ran non-linear models (see Table 11.2 in the appendix). In so doing, fear is correlated with neither a PRLWC nor a PRWC. On the contrary, anger and distrust are directly related to populist candidates. Although the probabilities between anger/distrust and the intention to vote for a PRLWC are more robust and clearer than voting for a PRWC, Fig. 11.3 illustrates positive probabilities for all of them.

The relation between populism and elitism versus anti-immigrant attitudes can be explained by the notion of the Manichean discourse between ‘natives’ and ‘immigrants’ (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2018). While populist attitudes foster a confrontation with the ‘other’ to evocate the general will of the people over those who retain the power, elitism impulses the social values and principles provided by the status quo. All in all, both types of attitudes seek the same outcome: to exclude the ‘other’, the one who is ‘different’, the ‘antagonist’, whether to be blamed for prior actions or to depict that all the ways, customs and social practices other than those performed by the status quo are morally defective or at least undesirable (Müller, 2016).

Populist and elitist attitudes also oppose each other when they are conducive to the electoral arena. As highlighted, populism can be seen as a ‘thin’ set of ideas, or worldview, or ideology (Hawkins & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2017; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2018; Van Hauwaert & Van Kessel, 2018). PRLWC in Latin America has been accompanied by a Bolivarian variety of socialism: twenty-first-century socialism. Inspired by the combination of these two ideological adscriptions, leaders such as Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, Evo Morales in Bolivia and Rafael Correa in Ecuador came to power as outsiders, mostly attacking mainstream parties and the ‘imperialism’ of the West, along with liberal-democratic institutions and the economic elites both within and outside their countries (Block, 2015; Collins, 2014). By framing, in their discourses, ‘new’ ideas associated with participatory democracy, citizen empowerment and active channels to bestow political power back to the ‘pure’ people, they repealed the status quo in their countries (Barr, 2017; De la Torre, 2017). Consequently, those who display more-elitist attitudes are inversely correlated to supporting a PRLWC but aiming to electorally support a PRWC. This may be explained by previous political experiences since, after the public split between the former presidents Rafael Correa (2007–2017) and Lenín Moreno (2017–2021), Ecuadorian society seems to be polarised between pro- and anti-Correa identities (Castellanos et al., 2021).

Furthermore, our findings show that negative emotions fuel anti-immigrant attitudes in individuals as a direct effect. This coincides with existing contributions in both migration and populism studies. Individuals who feel anger tend to be opposed to ‘open borders’ policies (Vasilopoulos et al., 2018), thereafter expressing negative attitudes toward immigrants. Relatedly, negative emotions can trigger the sense of relative deprivation in individuals, which derives from both populist and anti-immigrant attitudes, often supporting populist radical right-wing options with nativist views (Rothmund et al., 2019). Yet, our empirical evidence is not conclusive enough to suggest a significant nexus between anti-immigrant attitudes and the intention to vote for a PRWC.

Our results show that anti-immigrant attitudes relate negatively to the intention to vote for a PRLWC. This is because radical left-wing leaders in Latin America, such as Rafael Correa and Evo Morales, have tended to depict more-liberal policies towards immigrants. More specifically, in the case of Ecuador, the government of former President Correa extended political and social rights to foreign residents in the country (Ramírez & Zepeda, 2015). Conversely, nativism is usually present in populist radical right-wing rhetoric and policies (Jakobson et al., 2020; Rothmund et al., 2019).

As leaders play a prominent role in directing the people’s feelings toward a specific group – for instance, the antagonist (Laclau, 2005; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2013; Salmela & von Scheve, 2017) – it is also important to clarify that, in Ecuador thus far, there is no ‘openly nativist’ radical political leader or party who can channel these anti-immigrant attitudes and negative emotions. Yet, the larger the presence of immigrants in Ecuador, the greater the salience of this topic on party and candidate manifestos (González-Paredes et al., 2022).

As indicated, we control our SEMs by incorporating institutional trust, age, education, income and religion. Institutional trust significantly correlates with elitism, populism and anti-immigrant attitudes, in one model or another. A positive variation in the levels of trust in public institutions has a negative effect on the probability of holding anti-immigrant (Odds Ratios [OR] = 0.15, p < 0.001 [Model 1]) and populist attitudes (OR = 0.23, p < 0.001 [Model 1]). To a great extent, those of the electorate who (strongly) trust Ecuadorian public institutions tend to have slightly more elitist attitudes (OR = 0.06, p < 0.05 [Model 2]). Since public institutions (and the elite), in the eyes of individuals who distrust them the most, are reluctant to regulate – even restrict – immigration, this functions as a direct effect in anti-immigrant attitudes.

Being evangelical and less-educated (i.e., primary and secondary level) directly triggers the likelihood of voting for a PRLWC (OR = 0.23, p < 0.001; OR = 0.26, p < 0.001), while constraining anti-immigrant attitudes (OR = 0.14, p < 0.05). This, of course, depends on the supply-side of a particular leader. In this case, the image of Rafael Correa as a populist radical left-wing leader is suggested in our model and the presidential candidate for the 2021 election, Andrés Arauz, was an unambiguous inspiration both for the design of our question but also for the way in which respondents answered it. In our online survey, we questioned the extent to which respondents would vote for a pro-Correa candidate, assuming that re-election rules prevent the return of Correa to the presidency; however, his approval rate is higher than any other candidate in the country for the 2021 presidential elections. Overall, controls have a moderate impact on populist and anti-immigrant attitudes.

6 Conclusion

As a result of increasing migration inflows in Ecuador in recent years, the demand side of Ecuadorian politics has paid close attention to the presence of immigrants as a salient issue. Both the ruling government and the opposition, as well as a substantive share of public opinion, have expressed concerns about the ongoing wave of Venezuelan migration throughout Latin America and a wide majority of immigrants – particularly Colombians, Cubans and Venezuelans – have been perceived as the ‘antagonist’ by natives. Considering this context of rising anxiety for Ecuadorians over Venezuelan immigration, we focused in this chapter on emotions and the political psychology of the voter, in order to explore to what extent the emotional underpinning and anti-immigrant attitudes of Ecuadorian voters are associated with their populist and elitist attitudes. Bridging this chapter in the junction of the secondary and tertiary migration crisis types (see Jakobson et al., Chap. 1 in this book), we used individual-level data and created several models in which we combined latent and observable variables and unpacked the nexus between different negative emotions, attitudes and prospective electoral behaviour.

Our findings supported each of our hypotheses. First, we reported that populist attitudes significantly lead to higher immigrant attitudes. Second, populist attitudes were also positively correlated with the intention to vote for a PRLWC, while elitism was less likely to display a similar outcome. Third, having negative emotions – predominantly anger and distrust – towards the presence of Americans, Colombians, Cubans, Peruvians and Venezuelans in Ecuador increased the probability of depicting anti-immigrant attitudes and voting for populist choices. Fourth, this set of restrictive or negative attitudes towards immigrants was inversely correlated with the intention of voting for a PRLWC. Overall, our results showed that the nexus between negative emotions and anti-immigrant attitudes, as well as between populism and restrictive or negative attitudes toward immigrants, is the most powerful one in explaining the complex interaction of political attitudes with the political psychology of the voter.

Conscious of working with a non-probabilistic sample – a major limitation in generalising our findings – we encourage scholars and practitioners interested in the interaction between emotions, immigrant policies and political attitudes to use our SEMs, with their more sophisticated sample designs, as a springboard to prospective contributions on this topic. As a future research agenda, we also suggest better calibrating the ideological variable and maybe including the intention to vote for a populist radical right-wing option. Although this decision can saturate SEMs, it might bring together a more comprehensively significant relation between political attitudes and the intention to vote for populist candidates, as well as a more cohesive dialogue between Latin American and European contexts. Finally, with our results, we invite future contributions to make a clearer distinction between the supply- and demand-side of populism in the empirical component. This may reduce even more the methodological limitation related to a possible problem of endogeneity when it comes to test the connection of populist support with populist attitudes.

Notes

- 1.

We have chosen to use ‘anti-immigrant’ and not ‘anti-immigration’ attitudes to reflect political processes specifically toward immigrants and not towards future waves of immigration (Pedroza, 2020).

- 2.

Former president Rafael Correa is the best representative of the radical left-leaning wave of populism, associated with twenty-first-century socialism, in Ecuador (De la Torre, 2017).

- 3.

Importantly, Ecuador has had a long-standing trajectory of populism from left- and right-wing, in government and/or opposition, since the 1930s (De la Torre, 1996; Ríos-Rivera & Umpierrez de Reguero, 2022; Ulloa-Tapia, 2021). Along with Argentina and Peru, Ecuador has overall been one of the most influential cases in Latin America in terms of populism.

References

Acosta, D., & Freier, L. F. (2015). Turning the immigration policy paradox upside down? Populist liberalism and discursive gaps in South America. International Migration Review, 49(3), 659–697.

Acosta, A., López, S., & Villamar, D. (2005). Las remesas y su aporte para la economía ecuatoriana. In G. Herrera, M. C. Carrillo, & A. Torres (Eds.), La migración ecuatoriana: Transnacionalismo, redes e identidades (pp. 227–252). FLACSO.

Akkerman, A., Mudde, C., & Zaslove, A. (2014). How populist are the people? Measuring populist attitudes in voters. Comparative Political Studies, 20(10), 1–30.

Barr, R. R. (2017). The resurgence of populism in Latin America. Lynne Rienner.

Block, E. (2015). Political communication and leadership: Mimetisation, Hugo Chávez and the construction of power and identity. Routledge.

Brumat, L., Acosta, D., & Vera-Espinoza, M. (2018). Gobernanza migratoria en América del Sur: Hacia una nueva oleada restrictiva? In L. Bizzozero Revelez & W. Fernández Luzuriaga (Eds.), Anuario política internacional and política exterior 2017–2018 (pp. 205–211). FCS, Cruz del Sur.

Canovan, M. (1999). Trust the people! Populism and the two faces of democracy. Political Studies, 47(1), 2–16.

Castellanos, A. S., Dandoy, R., & Umpierrez de Reguero, S. (2021). Between a rock and a hard place: Ecuador during the Covid-19 pandemic. Revista de Ciencia Política, 41(2), 321–251.

Close, C., & Van Haute, E. (2020). Émotions et choix de vote: Une analyse des élections 2019 en Belgique. In J. B. Pillet, P. Baudewyns, K. Deschouwer, A. Kern, & J. Lefevere (Eds.), Les Belges haussent leurs voix (pp. 125–152). Presses Universitaires de Louvain.

CNE. (2009). Ley orgánica electoral y de organizaciones políticas: Código de la democracia (suplemento del registro oficial, No. 578). Consejo Nacional Electoral.

CNE. (2017). Registro electoral 2017. Consejo Nacional Electoral.

Collins, J. N. (2014). New experiences in Bolivia and Ecuador and the challenge to theories of populism. Journal of Latin American Studies, 46(1), 59–86.

Cuevas, E. (2018). Reconfiguración social en Lima: Entre la migración y la percepción de inseguridad. Urvio, 23, 73–90.

De la Torre, C. (1996). Un solo toque: populismo y cultura política en Ecuador. Centro Andino de Acción Popular.

De la Torre, C. (2017). Populism in Latin America. In C. Rovira Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, & P. Ostiguy (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of populism (pp. 181–197). Oxford University Press.

El Correo. (2003, May 4). Ecuador: Xenofobia contra colombianos y peruanos. Diario El Correo. http://www.elcorreo.eu.org/IMG/article_PDF/Ecuador-xenofobia-contra-colombianos-y-peruanos_a1609.pdf. Accessed 23 Feb 2022.

El Universo. (2004, August 4). Secuestro ‘express’ cambió su modalidad en Ecuador. Diario El Universo. https://www.eluniverso.com/2004/08/04/0001/10/7D1EDD3451694EF1A69D027099B9181C.html. Accessed 23 Feb 2022.

El Universo. (2019, January 21). Otto Sonnenholzer: Se pedirá un pasado judicial apostillado a ciudadanos venezolanos. Diario El Universo. https://www.eluniverso.com/noticias/2019/01/21/nota/7150451/otto-sonnenholzner-se-pedira-pasado-judicial-apostillado-ciudadanos. Accessed 23 Feb 2022.

Finn, V., & Umpierrez de Reguero, S. (2020). Inclusive language for exclusive policies: Restrictive migration governance in Chile, 2018. Latin American Policy, 11(1), 42–61.

Global Digital Report. (2019). Digital 2019: Global internet use accelerates. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2019-ecuador

González-Paredes, S., Jara-Alba, C., Orcés Pareja, L., & Umpierrez de Reguero, S. (2022). Actitudes populistas, emociones negativas y posición partidaria frente a la inmigración en Ecuador. In I. Ríos Rivera & S. Umpierrez de Reguero (Eds.), Populismo y comportamiento político en Ecuador: Incorporando la agenda ideacional. Universidad Casa Grande.

Hamidou-Schmidt, H., & Mayer, S. J. (2020). The relation between social identities and outgroup hostilities among German immigration-origin citizens. Political Psychology, 42(2), 311–331.

Hawkins, K., & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2017). An ideational approach to populism. Latin American Research Review, 52(4), 1–16.

Hawkins, K., Riding, S., & Mudde, C. (2012). Measuring populist attitudes (Committee on Concepts and Methods Working Paper No. 55). University of Georgia.

Hawkins, K., Rovira Kaltwasser, C., & Andreadis, I. (2020). The activation of populist attitudes. Government and Opposition, 55(2), 283–307.

Hox, J., & Berchger, T. (1998). An introduction to structural equation modeling. Family Science Review, 11, 354–373.

Hurtado, O. (2018). Ecuador entre dos siglos. Penguin Random House.

INEC. (2019). Registro estadístico de entradas y salidas internacionales 1997–2018. Ecuadorian Institute of Statistics and Census.

Ivarsflaten, E. (2008). What unites right-wing populists in Western Europe? Re-examining grievance mobilization models in seven successful cases. Comparative Political Studies, 41(1), 3–23.

Jakobson, M.-L., Saarts, T., & Kalev, L. (2020). Radical right across borders? The case of EKRE’s Finnish branch. In T. Kernalegenn & É. van Haute (Eds.), Political parties abroad (pp. 21–38). Routledge.

Jara-Alba, C. (2017). Naturaleza económica e impacto macroeconómico de las remesas de los emigrantes. Caso Ecuador. Período 1994 a 2013 (Unpublished doctoral thesis). Universidad de Córdoba.

Laclau, E. (2005). On populist reason. Verso.

Lamprianou, I., & Ellinas, A. E. (2019). Emotion, sophistication and political behavior: Evidence from a laboratory experiment. Political Psychology, 40(4), 859–876.

Lodge, M., & Taber, C. (2000). Three steps toward a theory of motivated political reasoning. In A. Lupia, M. McCubbins, & S. Popkin (Eds.), Elements of reason: Cognition, choice, and the bounds of rationality (pp. 182–213). Cambridge University Press.

Malo, G. (2021). Between liberal legislation and preventive political practice: Ecuador’s political reactions to Venezuelan forced migration. International Migration, 60(1), 92–112.

Meléndez, C., & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2019). Political identities: The missing link in the study of populism. Party Politics, 25(4), 520–533.

Mudde, C. (2004). The populist zeitgeist. Government and Opposition, 39(4), 541–563.

Mudde, C. (2013). Populist radical-right parties in Europe. Cambridge University Press.

Mudde, C. (2017). The populist radical right: A reader. Routledge.

Mudde, C., & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2013). Exclusionary vs inclusionary populism: Comparing contemporary Europe and Latin America. Government and Opposition, 48(2), 147–174.

Mudde, C., & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2018). Studying populism in comparative perspective: Reflections on the contemporary and future research agenda. Comparative Political Studies, 51(13), 1667–1693.

Müller, J. W. (2016). What is populism? University of Pennsylvania Press.

Ochoa Espejo, P. (2011). The time of popular sovereignty: Process and the democratic state. Penn State University Press.

Pedroza, L. (2020). A comprehensive framework for studying migration policies (and a call to observe them beyond immigration to the west) (GIGA Working Papers No. 321). German Institute of Global and Area Studies.

Ramírez, J., & Umpierrez de Reguero, S. (2019). (E)migración y participación electoral: Análisis longitudinal del voto en el exterior de Ecuador. Revista Odisea, 6, 31–64.

Ramírez, J., & Zepeda, B. (2015). El desafío de las poblaciones en movimiento. In B. Zepeda & F. Carrión (Eds.), Las Américas y el mundo: Ecuador 2014 (pp. 141–174). FLACSO.

Ramírez, J., Linares, Y., & Useche, E. (2019). (Geo)políticas migratorias, inserción laboral y xenofobia: Migrantes venezolanos en Ecuador. In C. Blouin (Ed.), Después de la llegada. Realidades de la migración venezolana (pp. 1–29). Pontificia Universidad Católica de Perú.

Rico, G., Guinjoan, M., & Anduiza, E. (2017). The emotional underpinnings of populism: How anger and fear affect populist attitudes. Swiss Political Science Review, 23(4), 444–461.

Rinken, S. (2015). Actitudes hacia la inmigración y los inmigrantes: ¿En qué es España excepcional? Migraciones, 37, 53–74.

Ríos-Rivera, I., & Umpierrez de Reguero, S. (2022). Populismo y comportamiento político en Ecuador: Incorporando la agenda ideacional. Universidad Casa Grande.

Rothmund, T., Bromme, L., & Azevedo, F. (2019). Justice for the people? How justice sensitivity can foster and impair support for populist radical-right parties and politicians in the United States and Germany. Political Psychology, 41(3), 479–497.

Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2014). The responses of populism to Dahl’s democratic dilemmas. Political Studies, 62(3), 470–487.

Salmela, M., & von Scheve, C. (2017). Emotional roots of right-wing political populism. Social Science Information, 56(4), 567–595.

Schultz, A., Müller, P., Schemer, C., Wirz, D. S., Wettstein, M., & Wirth, W. (2017). Measuring populist attitudes on three dimensions. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 30(2), 316–326.

Schurr, C. (2013). Towards an emotional electoral geography: The performativity of emotions in electoral campaigning in Ecuador. Geoforum, 49, 114–126.

Ulloa-Tapia, C. (2021). ¿Después del populismo qué nos queda en Ecuador y Venezuela? Vacío institucional y crisis. Estancias, 1(2), 263–289.

Valdés, R. T. (2017, July 14). Cubanos en Ecuador son víctimas de xenofobia y discriminación. Radio Televisión Martí. https://www.radiotelevisionmarti.com/a/cuba-ecuador-migrantes-cubanos-discriminacion-xenofobia-/149011.html. Accessed 23 Feb 2022.

Van Hauwaert, S. M., & Van Kessel, S. (2018). Beyond protest and discontent: A cross-national analysis of the effect of populist attitudes and issue positions on populist party support. European Journal of Political Research, 57(1), 68–92.

Vasilopoulos, P., Marcus, G. E., Valentino, N., & Foucault, M. (2018). Fear, anger and voting for the far right: Evidence from the November 13, 2015, Paris terror attack. Political Psychology, 40(4), 679–704.

Verney, M. H. (2009). Unmet refugee needs: Colombian refugees in Ecuador. Forced Migration Review, 32, 60–61.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to Victoria Finn, Angeliki Konstantinidou, Jenny Money and Daniela Vintila, as well as the editors of this volume, for their helpful remarks on previous versions. We also thank the organisers of and participants in the ECPR 2020 General Conference and the International Research Conference ‘The Anxieties of Migration and Integration in Turbulent Times’ hosted by the Migration and Integration Research and Networking (MIRNet) project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Umpierrez de Reguero, S., González-Paredes, S., Ríos-Rivera, I. (2023). Immigrants as the ‘Antagonists’? Populism, Negative Emotions and Anti-immigrant Attitudes in Ecuador. In: Jakobson, ML., King, R., Moroşanu, L., Vetik, R. (eds) Anxieties of Migration and Integration in Turbulent Times. IMISCOE Research Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-23996-0_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-23996-0_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-23995-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-23996-0

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)