Abstract

This paper examines the role of individuals’ emotions in determining their concerns about international migration. For the empirical analysis, we exploit little-explored information in the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) data on individuals’ negative emotions, e.g., anger, fear, and sadness. We find that the frequency of experiencing negative emotions is positively associated with immigration concerns. Moreover, we show that the relationship varies across employment status, birth cohort, and social media usage. Our analysis also underscores the real-life consequence of emotions by demonstrating their positive association with support for far-right political parties among males, but not among females. Finally, we exploit the exogenous variation in negative emotions induced by the death of a parent to infer causality. Fixed effects regressions with instrumental variables exhibit a positive impact of negative emotions on immigration concerns among females, but no significant effects are found among males. Further investigation into channels driving these gender differences in results underscores gender differences in roles played by other concerns that often carry over to determine individuals’ immigration concerns, e.g., concerns about international terrorism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Extensive social science research attributes functional utility to individuals’ emotions (Loewenstein 1996, 2000; Parrott 2002; Lerner et al. 2015). Accordingly, individuals’ experience of a range of emotions can underpin their disparate behaviors, going beyond standard cost-benefit considerations. For instance, the empirical research shows how changes in emotions predict the risk of domestic violence (Card and Dahl 2011), economic preferences (Cohn et al. 2015; Meier 2022), labor productivity (Oswald et al. 2015), and income in later life (De Neve and Oswald 2012). More related to this paper’s scope, negative emotions have been shown to shape individuals’ crucial policy preferences, e.g., threat perception of climate change (Davydova et al. 2018), immigration concerns (Brader et al. 2008; Poutvaara and Steinhardt 2018; Erisen et al. 2020), international terrorism (Huddy et al. 2005; Erisen et al. 2020), and even election outcomes (Meier et al. 2019; Rico et al. 2017).Footnote 1 Using the richness of the German Socio-Economic Panel data (SOEP, 1984–2019, v36), we contribute to this research strand by conducting a field study investigation. In particular, we spotlight the positive relationship between individuals’ frequency of experiencing a range of negative emotions, particularly anger, fear, and sadness, and their concerns about international immigration and ensuing political behavior.Footnote 2

Recently, international immigration has become a prominently salient political topic in the Western world. In response to increased immigration, the political equilibrium in many countries has shifted (away from far-left) towards anti-immigration far-right politics (Edo et al. 2019; Russo 2021; Davis and Deole 2021). New research shows how European citizens’ various concerns towards international immigration are crucial in shaping their views towards redistribution (Alesina et al. 2023, 2021; Edo et al. 2019) and can hinder EU-level cooperation on strategically essential issues (Erisen et al. 2020). Given immigration concerns’ vital importance for politics and subsequent policy-making, researchers attempt to unearth their determinants, listing, among others, exogenous increases in individuals’ education (Cavaille and Marshall 2019; d’Hombres and Nunziata 2016; Finseraas et al. 2018; Margaryan et al. 2021) and exposure to refugee inflows (Bursztyn et al. 2021; Deole and Huang 2024; Hangartner et al. 2019; Sola 2018).Footnote 3 Notably, the media’s representation of migration topics (Brader et al. 2008; Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart 2009; Benesch et al. 2019) and incidents of Islamist terror attacks (Finseraas et al. 2011; Schüller 2016) have also been shown to provoke anti-immigration views. Moreover, researchers underline the pertinence of life-changing and emotion-inducing events in generating anti-immigration views (Oswald and Powdthavee 2010; Finseraas et al. 2011; Schüller 2016). While emotional triggers are generally assumed to transmit the anti-immigration effects of terror events, such triggers have not been formally investigated. With detailed information on respondents’ emotional components of affective well-being (anger, fear, and sadness) and the estimation strategy used, we bridge this gap in research by focusing on the direct role played by emotions in explaining individuals’ immigration concerns.Footnote 4 We contribute to this emerging research strand by introducing a novel determinant of citizens’ immigration concerns, i.e., negative emotions.

As motivated in detail in the next section, we expect a positive relationship between the respondents’ frequency of experiencing negative emotions (anger, fear, and sadness) and their immigration concerns. Specifically, referring to extensive social science research (for reviews, see Lerner et al. 2015), we hypothesize that emotions can play integral and incidental roles in determining their views towards the outgroup. Consistent with the integral role of emotions, we argue that immigration can generate affective reactions in natives, which eventually determine their attitudes towards immigration (see Landmann et al. 2019). Economics research also considers the role of citizens’ integral reactions to immigration, i.e., their perceived impact of immigration on their economic and non-economic wellbeing, in determining immigration concerns (Card et al. 2012). Individuals’ integral emotions towards immigration are particularly relevant in the context of Germany as the emerging research shows that, in the aftermath of the 2015 European refugee crisis, citizens reported increased worries about immigration (Sola 2018; Deole and Huang 2024). Concerning the incidental role of emotions, research shows that incidental emotions have the potential to pervasively carry over from one situation to the next, affecting decisions that are seemingly unrelated to that emotion, e.g., consumption behavior (Garg and Lerner 2013), impatience (Lerner et al. 2012), and welfare concerns (Small and Lerner 2008; Deole 2019). In this regard, we argue that the negative valence associated with the emotions of anger, fear, and sadness carries over to evoke negative feelings towards immigrants, heightening individuals’ immigration concerns.

For the empirical analysis, we exploit the richness of the German panel data to obtain our variables of interest. The dependent variable records individuals’ concerns about immigration to Germany, taking values between one (not concerned at all) and three (very concerned). The general-natured survey question captures the immigration concerns of respondents from both sides of the political spectrum. In other words, being “very” concerned about immigration to Germany can represent the opposition to immigration of the far-right respondents and pro-immigration views of the far-left that the country should be more accommodating of immigrants.Footnote 5 Therefore, to bring more clarity to the message of this paper, we conduct additional investigation and ask whether negative emotions are correlated with respondents’ political preferences and the intensity of their support of populist political parties, i.e., Germany’s far-left and far-right political parties, respectively.

For our primary explanatory variables of interest, we employ multiple variables collected as part of the SOEP’s Affective Well-Being module (see Schimmack et al. 2008; Schimmack 2009; von Scheve et al. 2017). The module records individuals’ experiences of a range of negative emotions, mainly their self-reported frequency of experiencing anger, fear, and sadness in the past 4 weeks. Separately, for the instrumental variable estimation, we construct a single variable from the three disparate negative emotions, an index of negative emotions (NE index hereafter, more information later). As negative emotions have been available only since 2007, the estimation sample consists of information between 2007 and 2019.

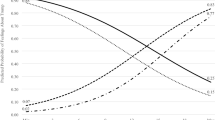

To give a preliminary idea of the baseline relationship, in Fig. 1a, we plot the sample mean of immigration concerns against different frequencies of anger, fear, and sadness experienced by sample respondents. Additionally, in Fig. 1b, we plot the average NE index against respondents’ different levels of immigration concerns. A broad reading of both figures underscores a positive relationship between negative emotions and immigration concerns, suggesting that increases in respondents’ frequency of experiencing anger, fear, and sadness are associated with increased immigration concerns. We employ Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) and Fixed Effects (FE) estimation methods to estimate the correlation between negative emotions and immigration concerns formally. The results confirm the earlier observation, suggesting a positive and statistically significant association. Our focus on the impact of emotions makes us consider the observed gender differences in processing and expressing emotions (Barrett et al. 2000; Garside and Klimes-Dougan 2002), which researchers have attributed to be a necessary driver of their divergent public policy preferences (Lerner et al. 2003). We report our baseline results separately for male and female subsamples in response. Our results indicate that the positive relationship holds for male and female subsamples and is robust to including numerous individual and regional characteristics as control variables. Moreover, the positive correlation between negative emotions and immigration concerns is more pronounced for irregularly employed individuals. When focusing on the birth cohort and the use of the online social network, we find mixed results for males and females. The positive association is larger for younger males who use social media more frequently than comparable males. At the same time, the association is more pronounced for older females with occasional social media use. Finally, we show that negative emotions are highly relevant for far-right political support, while they do not play any role in their support of far-left parties. We do not find evidence that negative emotions are associated with female political behavior.

Given the subjective nature of the variables of interest, we suspect the baseline relationship noted above is endogenous. In particular, we consider the following two sources. First, we suspect that if individuals consider immigration a collective disadvantage for their native country (e.g., immigration’s demographic impact on the host country), they will likely experience affective reactions, such as anger, fear, or sadness, posing the issue of endogeneity due to reverse causality (Shaver et al. 1987; Smith et al. 2008; Outten et al. 2012).Footnote 6 Second, we consider the possible existence of the omitted-variable bias. In other words, we suspect that time-variant uncontrolled or unobservable factors, such as media coverage of migration topics and individuals’ own experience with immigrants, may be correlated with within-person variations in negative emotions and changes in immigration concerns. To address the suspected endogeneity, following the idea in Meier (2022), we exploit the exogenous variation in negative emotions induced by an individual’s parent’s death and identify the causal impact of negative emotions on immigration concerns. We then employ fixed effects regressions with instrumental variables (IV FE). Although the death of a parent may be a shock, it could change various aspects of an individual’s life, making the defense of the exclusion restriction assumption incontestable. To give insightful results, we apply several robustness checks and discuss the limitations of the IV strategy. In contrast to earlier observations, IV FE results fail to find that within-person changes in negative emotions, on average, lead to variations in immigration concerns. Subsample analysis indicates that the impact of negative emotions on immigration concerns is found primarily among female respondents, statistically significant at the 5% significance level. At the same time, males do not register such an effect. Further investigation into channels driving these gender differences in results underscores gender different roles played by other concerns that often carry over to determine individuals’ immigration concerns, e.g., concerns toward international terrorism. We perform many robustness checks to support the main results of the paper.

Our efforts to investigate the role of negative emotions in determining individuals’ immigration concerns differ from earlier studies in three broad aspects. First, the availability of information on hundreds of thousands of respondents allows us to have a global perspective on the relationship between the range of negative emotions (anger, fear, and sadness) and immigration concerns. Second, our approach is distinct from the existing research relying on proxy indicators (Poutvaara and Steinhardt 2018), experimental strategies observing small samples (Rico et al. 2017; Brader et al. 2008; Lerner et al. 2003), and those investigating the role of immigration-related emotions (Landmann et al. 2019; Yitmen and Verkuyten 2020). Finally, different from earlier research, we conduct a supplementary analysis to address the suspected endogeneity and provide a causal interpretation of the main results (for more details, see Sect. 4.2). Moreover, it is noteworthy that, unlike the existing social psychology research, our analysis does not differentiate between the effects of distinct negative emotions on immigration concerns. Instead, we use the NE index, which helps us mitigate the issue posed by intricate interrelationships between these emotions. We discuss this and other limitations of our estimation strategy in Sect. 5.4.3.

2 Conceptual framework and literature review

2.1 Emotions and individual behavior

Nowadays, many social science subfields conceptualize and investigate the pertinence of individuals’ emotions for their behaviors and decisions. Lerner et al. (2015) summarize the main findings of this recent revolution in the science of emotions and underscore emotions’ potential to be pervasive, predictable, sometimes harmful, and sometimes beneficial decision-making drivers. Notably, the authors provide two views that help us make sense of the role of emotions in the context of this paper. As per the first view, emotions are “integral” to individual decision-making, operating at conscious and unconscious levels. Accordingly, a person’s feeling of gratefulness towards their school may lead them to donate a large sum of money to that school, irrespective of the financial constrain such a donation may be. The existing research describes myriad ways in which integral emotions override otherwise rational courses of action (for selective reviews, see Loewenstein 1996; Keltner and Lerner 2010). Following this reasoning, we expect individuals’ emotions towards foreigners, e.g., from their personal experiences of migration (good or bad), to determine their perception of international migration.

Second and more related to the paper’s scope, Lerner and authors underscore the “incidental” role of emotions. As per this view, incidental emotions have the potential to pervasively carry over from one situation to the next, affecting decisions that are seemingly unrelated to that emotion. Accordingly, people in good (bad) moods are likely to make optimistic (pessimistic) judgments (for reviews, also see Loewenstein and Lerner 2003; Keltner and Lerner 2010). For example, Quigley and Tedeschi (1996) show that incidental anger triggered in one situation can automatically elicit a motive to blame individuals in other situations unrelated to the source of anger. Similarly, Small and Lerner (2008) find how incidental anger or sadness—borne from an emotion-inducing event in the person’s life—shapes the respondent’s welfare policy preferences. Lerner et al. (2012) show that incidental sadness increases impatience and makes people more present-biased (i.e., wanting something immediately), bearing financial costs, a phenomenon they term as myopic misery. Following this line of argumentation, we expect changes in incidental negative emotions—induced by an event in individuals’ personal lives—will carry over and evoke negative feelings towards immigrants, heightening individuals’ immigration concerns. In extreme cases (perhaps hypothetical), individuals may blame immigrants for the deterioration of their emotional state.

In economics, George Loewenstein is often attributed to being the first to attempt to investigate the relevance of emotions for individual behaviors (Loewenstein 1996, 2000). In his research, the author described how the visceral factors— constituting a wide range of negative emotions (e.g., anger and fear), drive states (e.g., hunger, thirst, and sexual desire), and feeling states (e.g., pain)—can underpin individuals’ daily functioning, often affecting their disparate behaviors. Thanks to these earlier efforts, nowadays, economists readily admit the functional utility ascribed to individuals’ emotions, particularly positive emotions (e.g., happiness). Accordingly, positive emotions can save individuals’ time spent worrying about negative aspects of their lives, making them more risk-neutral (Meier 2022), advancing fertility decisions (Mencarini et al. 2018), increasing their electoral support for the incumbent (Ward 2020), and increasing the labor productivity of the employed (Oswald et al. 2015; Bellet et al. 2019).Footnote 7 More related, research shows that happier voters are less likely to oppose immigration (Panno 2018) or vote for far-right political parties (Algan et al. 2018).

Despite earlier influences, economists initially failed to scrutinize the influence of negative emotions on economic choices, and the attempts were primarily limited to laboratory studies (Haushofer and Fehr 2014, p. 866). However, recently, many field studies have found that a range of negative emotions, such as anger (Card and Dahl 2011; Meier 2022), fear (Cohn et al. 2015; Meier 2022), bitterness (Poutvaara and Steinhardt 2018), sadness (Krueger and Mueller 2012), and grief (Van den Berg et al. 2017), influence individual behaviors. More related to the paper’s scope, new research also underlines the bearing of negative emotions on national politics. In particular, researchers demonstrate that populist political parties often prioritize negative emotions in their political communications (Salmela and von Scheve 2018; Rico et al. 2017; Widmann 2021). For example, Widmann (2021) analyze 700,000 press releases and tweets from European political parties (including Germany) and show that, compared to mainstream political parties, populist parties, on both ends of the political spectrum, frequently employed negative emotional appeals (anger, fear, sadness, disgust) in their political communication than favorable appeals (joy, enthusiasm, pride, hope). As populist parties often appropriate immigration discourses, their recent successes in European elections justify negative emotions’ relevance for immigration and anti-terrorism policymaking in the region (see Doležalová et al. 2017; Salmela and von Scheve 2018; Davis and Deole 2021).

As noted earlier, this paper contributes to economics research by considering three negative emotions of similar valence (anger, fear, and sadness). This consideration is especially topical in Europe as, in response to the 2015 refugee crisis, extensive public debates questioned European countries’ ability to handle the massive inflows of asylum seekers from war-torn world countries. As per Landmann et al. (2019), these asylum inflows induced negative emotional reactions (anger, fear, sadness, and disgust) among German respondents, crucially determining their support for restrictive asylum policies and even Islamophobia. While there is no consensus in research on whether the effects of higher happiness are diametrically opposite to lower sadness levels (Lerner et al. 2004; Bodenhausen et al. 1994a, b; Krueger and Mueller 2012), our choice of focusing on negative emotions needs further supporting argument.Footnote 8 As von Scheve et al. (2017) elaborate, combining positive and negative emotions into a single indicator can result in the loss of valuable information relevant to understanding the impact of the phenomenon of interest. In particular, our use of an index constituting a range of similarly defined negative emotions makes it especially unfeasible to consider the similarly defined positive emotion (happiness) in our analysis. With these arguments in mind, we now motivate how each negative emotion shapes individuals’ attitudes towards the outgroup, increasing their anti- and pro-immigration concerns.

2.2 Negative emotions and immigration concerns

Anger and immigration concerns

We begin by hypothesizing the role played by anger. The emotion of anger represents rage, envy, resentment, and frustration (Shaver et al. 1987; Smith et al. 2008). Extensive existing research emphasizes the relevance of the emotion of anger in intergroup contact situations, with a particular focus on intergroup conflict and competition (DeSteno et al. 2004). Researchers show that anger can increase individuals’ reliance on stereotypes (Bodenhausen et al. 1994b; Wilder and Simon 2003) and can lead to prejudice toward outgroups. Their stereotyping and increased predispositions can bear substance for their immigration concerns. Notably, anger may amplify natives’ welfare concerns toward immigration, i.e., those concerned and angry toward the state of the country’s welfare system may blame immigrants perceiving them as taking advantage of the system and receiving government benefits without contributing to society. The existing research highlights the relevance of natives’ welfare concerns for their immigration concerns (Facchini and Mayda 2009) and voting behaviors and support for policies restricting immigrants’ access to benefits or services (Edo et al. 2019).

Moreover, according to Marcus (2021), anger helps individuals to identify non-compliance with established norms in their surroundings. Violations of their perceived norms can lead individuals to court interpersonal attacks, collective protests, and challenges to the outgroup (Smith et al. 2008). To this end, for those considering immigration as a departure from the norm, we expect that increases in anger can heighten the likelihood of individuals falling to a nativist view of nationality, reporting increased anti-immigration concerns. In addition, natives may hold immigrants, especially asylum seekers, personally responsible for their situation, making natives feel irritated and hostile towards immigration (Verkuyten 2004). To this end, existing research provides supporting evidence that anger renders citizens’ support for populism (Rico et al. 2017), mainly the anti-immigration far-right (Vasilopoulos et al. 2019) and also forged the “leave” vote during the Brexit referendum (Vasilopoulou and Wagner 2017).

Fear and immigration concerns

To theorize the role of fear, we first refer to the definition of the term xenophobia. Generally construed as anti-immigration fear, xenophobia refers to the fear of strangers (\(x\acute{e}nos=\) strange/foreign, \(ph\acute{o}bia=\) fear). Thus, we can expect that increases in the emotion of fear are likely to lead to an increase in an individual’s fear of strangers, including immigrants, resulting in their opposition to immigration. For instance, a fearful person may develop a fear of crime, terrorism, or loss of jobs to immigrants, which can lead them to view immigrants as a threat to their personal safety or economic security, resulting in negative attitudes toward immigrants and support for stricter immigration policies (Arendt et al. 2017; Dustmann and Preston 2007; Wigger et al. 2022; O’Rourke and Sinnott 2006; Ortega and Polavieja 2012).

In addition, recent research enlightens us on the mechanisms with which fear, in general, can determine immigration attitudes. At its core, fear helps individuals identify novelty (the unexpected) and re-assess their response to the uncertainty, changing individual decision-making from automaticity to a thoughtful/reflective deliberation of the available choices before them MacKuen et al. (2010). At the same time, however, fear is linked to impairing cognitive functioning, increasing preference for precautionary/protective measures (Huddy et al. 2005; Lerner et al. 2003). Moreover, as per Lerner et al. (2015), fear is intimately associated with individuals’ risk aversion and a low sense of control, causing fearful people to make pessimistic judgments of future events. Consequently, we expect that the emotion of fear will likely lead individuals to prefer more protective and precautionary immigration policy measures, heightening their immigration concerns.

Sadness and immigration concerns

People feel sad and perceive impersonal circumstances beyond human control to be the cause of their misfortune (Keltner et al. 1993). Sadness can channel individuals’ cognition in a negative direction, provoking many complicated emotions, such as hopelessness, suffering, disappointment, shame, neglect, and sympathy (Shaver et al. 1987, p. 1077). Below, we provide several arguments on how sadness can instigate both anti- and pro-immigration concerns, suggesting a cautious interpretation of the impact of sadness on the type of immigration concerns.Footnote 9 A caution is particularly relevant as Paolini et al. (2021) highlight the possibility that incidental and integral sadness can have opposing effects on the interethnic bias, a case especially likely in positive inter-ethnic contact situations. For instance, a sweet/helping gesture by the immigrant can induce a reduction in incidental sadness in individuals that can attenuate interethnic bias born from integral sadness. The authors find that during their real face-to-face contact with an ethnic tutor, individuals displayed higher interethnic bias when integrally sad. In contrast, incidental sadness had the opposite effects, i.e., individuals reporting lower interethnic bias than the reference group.

We begin the discussion by providing two assertions describing how those experiencing it due to personal or societal struggles can adopt negative attitudes toward groups of people they perceive as being different or “others” including immigrants. First, unlike anger, sadness is less likely to lead to excessive reliance on prejudice and stereotyping (Bodenhausen et al. 1994b; Wilder and Simon 2003), but it can influence individuals’ propensity to help others (Wilder and Simon 2003, p.160). Wilder and Simon elaborate on how changes in a sad person’s helping depend on their attention. Notably, if the sad person is focused inwardly, their propensity to help decreases as they are less likely to notice the need for aid, a case particularly likely when individuals are exposed to personal shocks such as the death of a loved one. We revisit this line of pondering in Sect. 5. Moreover, sadness can lead to a reduced ability to empathize with others (Xiao et al. 2021). This lack of empathy can make it more challenging to understand the experiences and perspectives of immigrants and their families, leading to a lack of support for immigration policies that promote inclusivity and diversity.

Second, sadness is likely to be more conducive to excessive noticing and carefully processing information in a contact situation (Wilder and Simon 2003, p.166), which can hinder individuals from establishing pleasant contact with an outgroup. To this end, sadness may also induce individuals to focus on the negative aspects of a contact situation, potentially leading to negative attitudes and biases towards the said outgroup, including immigration and immigration’s impact on the country and national culture. Moreover, as noted in Small and Lerner (2008, p.151), the negative valence associated with incidental sadness has the potential to trigger negatively biased attention towards others (also, see Johnson and Tversky 1983). The emotion of sadness can also proxy individuals’ disappointment and hopelessness (Shaver et al. 1987; Smith et al. 2008), motivating them to give up and withdraw from the situation (Dumont et al. 2003; Smith et al. 2008). As a result, those experiencing sadness may be less likely to engage with news and current events, potentially limiting their exposure to different perspectives and viewpoints on immigration. Sadness may indicate a low level of (psychological and physical) resources available to execute a given task. In this case, feelings of hopelessness generated by sadness may bring about a lower willingness to volunteer to help immigrants, resulting in individuals’ inhibition in allowing strangers to enter their country, fueling support for opposition towards further immigration.

While economics research on sadness is rare, researchers have studied its association with immigration concerns indirectly. For example, Poutvaara and Steinhardt (2018) investigate the association of individuals’ immigration concerns with their bitterness, which according to psychologists, ranges between anger and sadness, captures the sense of injustice (like anger), and, similar to sadness, also indicates helplessness (Poggi and D’Errico 2010; Linden and Maercker 2011).Footnote 10 Poutvaara and Steinhardt (2018) hypothesize that bitter people feel late down by fate or others, angry and helpless about their situation, want to fight back and report increased opposition towards immigration. Their finding suggests a positive association between bitterness and attitudes towards immigration, which aligns with our expectation of a positive association between a range of negative emotions, particularly anger and sadness, and immigration concerns.

In contrast to the arguments above, sadness can also activate implicit mood-repair motives among sad persons and change their pessimistic outlook. The mood repair can take place in two major ways, both having significant implications for our attempt to understand the impact of sadness on immigration concerns. First, sad individuals may indulge in mood-repairing motives by becoming more generous (Cialdini et al. 1973; Small and Lerner 2008, p. 152). Second, sad individuals may work to improve their control over the situation or change their feelings about it (Shaver et al. 1987, p. 1077). To achieve a better emotional state (less sadness), individuals may choose to be generous with immigrants or reduce negative views toward immigrants, reinforcing pro-immigration attitudes. Given the intricate implications of sadness for individuals’ views and behaviors toward immigrants, we suggest a cautious interpretation of the impact of sadness on the type of immigration concerns.

2.3 Gender differences in the relationship

In this subsection, we highlight the role of the respondents’ gender and provide arguments for why the baseline relationship should differ across gender. First, we discuss the possibility that men and women are different in processing and expressing their emotions, deciding to what extent their negative emotions should determine immigration concerns. Fischer et al. (2004) provide cross-country evidence from predominantly western countries (total 37) and find that men report more powerful emotions (e.g., anger), whereas women report more powerless emotions (e.g., sadness, fear). This finding is slightly different from the research by Brebner (2003), in which the author considers a dataset of 2199 respondents from Australia and 6868 observations from an international survey and finds that women score higher on all negative emotions than men, including anger, fear, and sadness. The existing research also finds that women show higher emotional awareness than men and display complexity and differentiation in articulating emotional experiences (Barrett et al. 2000).

Social psychologists often clarify that the gender difference in emotions is a product of the social and cultural context than biological differences (Garside and Klimes-Dougan 2002), indicating the pertinence of social norms in socialization and societal expectations of gender roles and how different genders express their emotions (Wood and Eagly 2002). For example, Fischer et al. (2004, p. 87) uncover that, in many cultures, men are expected to express powerful emotions (e.g., anger or frustration and price), while females are expected to be more empathetic in their expressions. Finally, the existing research underscores that the gender difference in emotions can have real-world implications for the gender gap in various outcomes. For example, Lerner et al. (2003) argue that gender differences in emotions account for the gender gap in risk perception, a necessary driver of divergent public policy preferences.

Second, we consider the possibility of gender differences in immigration concerns. There are several reasons why males and females may view immigration differently. While natives’ views about the economic impact of international immigration are critical in determining their immigration concerns (Dustmann and Preston 2007), the research indicates that immigration may economically affect different genders differently. Researchers find that females are more likely to worry about immigration’s impact on their employment and wages than males (Dustmann and Preston 2007, p. 30) and, on average, report more economic concerns over immigration than males (Davis and Deole 2021).

Natives may also be concerned about immigration’s impact on their community and the country’s cultural makeup and norms. Card et al. (2012) find that natives’ cultural concerns are far more critical in shaping their immigration policy preferences than their economic concerns. Dustmann and Preston (2007, p. 30) present evidence that women are much less concerned about immigration’s impact on national culture than men, evidence supporting how different genders view the cultural impact of immigration differently. Finally, recently, researchers considered the role of gender in the effect heterogeneity of their primary analysis. For instance, using German data, Benesch et al. (2019) show that the impact of media’s coverage of migration issues on respondents’ immigration concerns is remarkably more substantial among female respondents than males.Footnote 11 In view of our the aforementioned findings concerning the gender difference in emotions and immigration concerns, we invariably speak of our main findings separately for male and female subsamples in Sect. 5. In Sect. 5.4.1, we consider gender-specific channels that help us explain the gender differences in the estimates from specifications with an instrumental variable.

3 Data and variables

We employ high-quality SOEP data for empirical analysis, a wide-ranging representative panel dataset of private households in Germany (see Goebel et al. 2019). While the survey regularly records individuals’ immigration concerns, their negative emotions are available annually from 2007 onward. Consequently, we restrict the sample period to years between 2007 and 2019. The estimation sample consists of information on 266,241 individual-year observations, including 123,763 male and 142,478 female observations.

3.1 Immigration concerns

SOEP asks respondents the following question, which captures their immigration concerns: “How concerned are you about the immigration to Germany?” The individuals’ responses to this question are scaled as one (very concerned), two (somewhat concerned), and three (not concerned at all). We re-scale these responses to generate our primary dependent variable, immigration concerns, which ranges from one (not concerned at all) to three (very concerned), where higher values represent individuals’ heightened concerns about immigration. Table 1 reports the statistical summary of the variables used. While in columns 1–2, we show overall sample means and standard deviations, columns 3–6 report information separately for female and male respondents in the sample. From the table, we observe that, on average, German respondents are concerned about immigration as indicated by the mean value of around 2 (somewhat concerned). We also observe that males and females report different levels of immigration concerns, a difference minor in magnitude but statistically significant.

As noted earlier, the survey question recording immigration concerns is rather general and does not convey whether the concerns reported by individuals are anti- or pro-immigration in nature. Figure 2 plots the average immigration concerns against individuals’ self-reported placement on the political spectrum, indicated by an 11-pointer left-right political scale and available in 2009, 2014, and 2019. We make the following observations. Compared to the sample mean of immigration concerns (mean of 1.94), which is close to the average immigration concerns reported by those belonging to the political center, individuals on the right side of the political spectrum report very high levels of immigration concerns. Noteworthily, although individuals on the left side of the political spectrum report lower immigration concerns than the sample average, their average immigration concerns are away from scale one (not concerned at all) and close to scale two (Somewhat concerned). Notably, those on the extreme left of the political spectrum, though they make only about 1% of the sample, are more concerned about immigration than center-left individuals, and their average immigration concerns are close to the sample mean. Nevertheless, for the majority of the sample, we conclude that going from left to right on the political scale is associated with increases in immigration concerns. As a consequence of this graphical evidence, we also consider the respondents’ support and intensity of their support of populist political parties as additional outcome variables.

Immigration concerns and political attitudes. Source: SOEP v36, reduced estimation sample, own calculation. Notes: This figure shows the relationship between respondents immigration concerns and their political attitudes with 95% confidence intervals. For its construction, the sample is restricted to those who reported political attitudes in 2009, 2014, and 2019. The value of political attitudes ranges from zero (extreme_left) to ten (extreme_right). The horizontal reference line (dotted) depicts the sample mean of immigration concerns, which is 1.9430

3.2 Negative emotions

SOEP records information on the individuals’ negative emotions: anger, fear, and sadness. It obtains three different variables by asking the following question: “I will now read off a number of feelings. For each one, please state how often you experienced this feeling in the last four weeks. How often have you felt angry/fearful/sad?”. The responses record respondents’ frequency of feeling each emotion ranging from one (very rarely) to five (very often). Table 1 shows that German respondents, on average, report the frequency of feeling negative emotions between 2 (rarely) and 3 (occasionally). Notably, female respondents report a higher frequency of all negative emotions than male respondents. The difference in negative emotions between genders is also statistically significant, an observation in line with psychology research (Brebner 2003) and further motivates our analysis of gender-specific effect heterogeneity in the baseline results (see Sect. 2.3 for more details).

For the main analysis, we construct our primary explanatory variable, NE index, by applying principal component analysis (PCA) on the three emotions noted above. The method allows us to generate a single variable (NE index) by accounting for the information that captures individuals’ frequency of experiencing anger, fear, and sadness. The strategy performs orthogonal transformation to transform anger, fear, and sadness into three principal components that are uncorrelated with each other (see Kalfa and Piracha 2018),Footnote 12 In the empirical analysis, we employ the first component as NE index since it contains the largest variation, about 60%, of the three emotions in the estimation sample. Moreover, we use two alternative indexes to show that the main results are robust to the methodology used to construct the index. First, we employ the scale average method and generate a variable, scale average, that is simply the average of our three negative emotions and ranges between one and five. Second, we construct the scale sum index, which is the sum of the three emotion variables and ranges from three to fifteen. Section 5 discusses the results estimated using the alternative indexes.

3.3 Other covariates

Now we provide supporting arguments for our choice of the control variables. The first set of control variables includes the respondent’s demographic characteristics that form pertinent determinants of the individual’s immigration concerns and may also be correlated with their negative emotions. These variables include the respondent’s age (in years), gender (female/male), regional location (rural/non-rural), and marital status (married/not-married). Hainmueller and Hiscox (2007) describe the pertinence of the respondent’s education and occupational skills by showing that those with higher education levels and working in higher occupational skills support all immigration types. In response, we employ their education level (measured in years of schooling) and years of working experience as control variables. We also control for the respondent’s labor force status represented by ten dummy variables, indicating whether the respondent is working, working but not working past 7 days, unemployed, non-working, or in six other categories of non-working respondents, e.g., aged 65 and older, on maternity leave, serving in the military-community, etc. Table 1 reports the summary statistics of these variables. Accordingly, around 60% of the observations are working, and 4% are unemployed. Around 21% of the observations are non-working because they are 65 or older, which indicates that our sample also includes individuals retired from service.

As noted earlier, macroeconomic conditions also form essential associations with respondents’ immigration concerns. To account for the salient association between the immigration population share and citizens’ immigration concerns, our estimation model includes the state-level growth rate of the foreign population. Additionally, we include state-level indicators, sourced from Federal Statistical Office, such as the logarithm of GDP per capita and unemployment rates. Table 1 presents a statistical summary of these indicators.

4 Empirical strategy

4.1 Fixed effects model

Our empirical investigation begins by presenting the estimates of the association between individuals’ negative emotions and immigration concerns. To do so, we estimate the following fixed effects model:

where \(Y_{it}\) is immigration concerns of individual i interviewed in year t. \(NE\ index_{it}\) represents the value of the negative emotions index (NE index) of the individual i. \(\varvec{X_{it}}\) is a vector of individual-level characteristics shown in Table 1. These include age (including its polynomials, quadratic and cubic terms) and a set of dummy variables indicating whether the respondent resides in the rural region or is married. Additionally, the individual-level controls include the respondents’ years of education and working experience with their quadratic terms as well as dummy indicators for different labor force statuses. \(\varvec{Z_{st}}\) is a vector of annual state-level macroeconomic characteristics summarized in Table 1. \(\lambda _i\) indicates person-fixed effects that control for level differences in immigration concerns between respondents due to individual-specific time-invariant factors.Footnote 13 The term \(\lambda _s\) represents a set of dummy variables indicating state fixed effects, which control for state-level differences in time-invariant (un)observable factors influencing the outcome. The month fixed effects, \(\lambda _m\), are a set of dummy variables for the 12 calendar months, controlling for the possibility that respondents recorded systematically different answers in immigration concerns and negative emotions in different months. For instance, individuals may report lower concerns as well as negative emotions during holidays. \(\lambda _t\) is a set of survey year dummies that control for the average change in immigration concerns and their influencing factors over time. \(\varepsilon _{it}\) is the error term. We cluster standard errors at the individual level. As noted in Sect. 3, female respondents in Germany report more significant immigration concerns and record a higher frequency of negative emotions than their male counterparts. Therefore, in addition to average effects, following our expectations noted in Sect. 2.3, we present estimates separately for female and male subsamples.

4.2 Fixed effects model with instrumental variables (IV FE)

4.2.1 Potential endogeneity and the IV FE strategy

Next, we discuss the endogeneity issue in the primary regressor of interest, i.e., \(NE\ index\). We suspect many sources of endogeneity that can bias the estimates presented in Eq. 1. First, we suspect endogeneity due to omitted variable bias. Although the model accounts for person fixed effects that control for time-invariant individual-specific factors, time-variant unobservable variables contained in \(\varepsilon _{it}\) can influence both immigration concerns and negative emotions and bias our estimates. Examples of unobserved factors include many immigration-related triggers, such as individuals’ experience with foreigners in daily life and media coverage of migration topics. Individuals’ contact with immigrants and their first-hand experience of hearing refugee immigrants’ plight can induce negative emotions (e.g., sadness). At the same time, however, individuals’ better understanding of the outgroup may also reduce their anti-immigration attitudes. In this case, \(\beta _1\) in Eq. 1 may be downward biased. In contrast, the excessive media coverage of crimes committed by immigrants (e.g., the 2015 New Year’s Eve sexual assaults in Cologne, see Arendt et al. (2017); Wigger et al. (2022)) may increase individuals’ frequency of experiencing negative emotions, especially fear and anger, and simultaneously increase their immigration concerns, positively biasing the fixed effects model’s estimates.Footnote 14 Second, we suspect endogeneity due to the possibility of reverse causality in the variables of interest. That is, individuals intensely concerned about immigration may show increased negative emotions.

We implement the instrumental variables (IV FE) strategy to overcome the suspected endogeneity. We exploit the exogenous variation in the NE index induced by the instrumental variable and estimate the following first-stage regression:

where \(IV_{it}\) is the instrumental variable. From the first stage, we obtain the predicted negative emotions (denoted as \(\widehat{NE\ index_{it}}\)), which we substitute with our endogenous regressor in Eq. 1 and estimate the second-stage equation. Next, we introduce the instrumental variable and discuss its validity.

4.2.2 Instrumental variable: death of a parent

Extensive research on the effects of grief or bereavement finds that a relative’s death is detrimental to surviving members’ emotional state (Stroebe et al. 2007; Kravdal and Grundy 2016; Liberini et al. 2017; Persson and Rossin-Slater 2018; Meier 2022) and even increases their mortality risk (Stroebe et al. 2001, 2007; Boyle et al. 2011; Van den Berg et al. 2011). While reactions to grief may vary in nature and intensity across individuals, researchers agree that the loss often induces clinically significant adverse affective reactions, such as despair, fears, anxiety, and anger in the surviving members (for reviews, see Stroebe et al. 2007). More relevant for our study, recently, Meier (2022) applies the death of a parent or a child in their investigation of the link between emotions and risk attitudes. We now provide supporting arguments for our choice of the IV, i.e., the death of the respondent’s parent.

We first review the existing research to support our expectation that the parent’s death increases the frequency of experiencing anger, fear, and sadness among the surviving respondents. Research shows that sadness is among the most immediate and prominent emotional reactions experienced by the grieving (Bonanno et al. 2008) and has real-life implications for their economic well-being (Van den Berg et al. 2017). Among other immediate reactions, Barr and Cacciatore (2008) show that bereavement due to losing a loved one can instigate distinct fears (fear of the unknown, fear of own death) in the surviving members. However, not all emotional reactions to personal loss are immediate, e.g., anger, acceptance of the death, and changed circumstances. For instance, in their empirical investigation of the Stage Theory of Grief, Maciejewski et al. (2007) find that while the grieving individual slowly learns to accept the situation after an initial shock, the stage of anger peaks around the 5 months after the loss. Consequently, as a parent’s death is likely to instigate all three negative emotions in an individual, the NE index, capturing individuals’ three distinct emotions, is predicted to increase in response to the subsequent bereavement. In our IV FE estimation strategy, we exploit the exogenous variation in the NE index induced by the individuals’ parent’s death to estimate the impact of negative emotions on immigration concerns. Noteworthily, the death of a parent is an immigration-unrelated emotion-inducing trigger, which sets us apart from existing (psychology) literature (Landmann et al. 2019; Yitmen and Verkuyten 2020). As discussed in Sect. 2.1, emotions have the potential to carry over from one situation to the next. Therefore, we expect changes in individuals’ negative emotions induced by an immigration-unrelated event to impact their immigration concerns.

To generate the instrumental variable, we use many SOEP questions recording whether the individual’s parent (mother/father) died in the interview year or one year before. Using this information, we construct a dummy variable \(death_{it}\), indicating whether a parent of individual i died in the last two years, allowing us to capture the variation in \(death_{it}\) across individuals and time. This variable definition allows us to account for the affective reactions induced immediately (e.g., fear and sadness) and those with a slight delay (e.g., anger) after the death event (see Maciejewski et al. 2007). In the estimation sample, 4,468 individuals reported that they experienced bereavement due to their parent’s death at least once in the sample period. In Table 1, we report summary statistics of the instrumental variable. Noteworthily, both male and female respondents report similar mean values of the IV. However, existing research shows that gender differences may exist in the ways bereavement affects different genders. For one, daughters may feel the bereavement loss more intensely as they tend to have more contact with their parents as adults and may also be more involved in caregiving (Umberson 2003).Footnote 15 On the other hand, it is also likely that females are better in dealing with the loss than males as they have efficient coping strategies and alternative support networks than men (Umberson 2003). Furthermore, research shows that women are more confronting and expressive of their emotions, which helps their faster recovery from bereavement (Stroebe et al. 2001). These differences in the expectation of the first-stage relationship between bereavement and the NE index provide an additional supporting argument for considering the gender differences in the baseline effect.

IV relevance

We now provide visual evidence supporting the first-stage relationship. For this exercise, we employ detailed information about the exact month of the parent’s death present in the SOEP and show whether a parent’s death instigates negative emotions in the surviving children.Footnote 16 Figure 3 plots the evolution of the demeaned NE index months before and after bereavement only for those respondents who reported the death of at least one parent during the sample period. We observe no evidence of significant changes in the NE index before the death event, highlighting no substantial anticipation of parents’ death by individuals. A statistically significant increase in NE index is observed in the month of the parent’s death (shown by the dotted vertical reference line). By the end of the first year, negative emotions have decreased but are still statistically significantly above the pre-death mean value. Overall, we conclude that bereavement induces negative emotions in the surviving child.

Death of a parent and negative emotions. Source: SOEP v36, reduced estimation sample, own calculation. Notes: This figure shows the relationship between the demeaned NE index and the distance (in months) to the death of a parent with 95% confidence intervals. The sample for this figure is restricted to those who reported the death of a parent during the observation period. The horizontal reference line (dashed) depicts the average of the demeaned NE index, which is zero

Next, we report the results of our formal analysis and further discuss the IV’s validity. First, in column (3) of Table 5, we report our first-stage results. The estimates indicate that bereavement due to the parent’s death significantly increases surviving individual’s NE index. The first-stage effective F statistics are well above 10 and also above the critical value (23) for a confidence level \(\alpha =5\%\) and \(10\%\) of worst case bias (Olea and Pflueger 2013), supporting the relevance assumption of the IV. While the timing of a parent’s death is exogenous and is challenging to predict with certainty, indications such as worsening of the parent’s health before the actual death are difficult to ignore and question the unpredictability assumption. Beyond descriptive evidence of no anticipation presented in Fig. 3, in Appendix E, we formally test our results’ vulnerability concerning the exogeneity assumption. To do this, we generate a variable indicating 15 months before the death as an additional covariate. Our results show that the difference in the NE index between 15 months before the death and the reference period is insignificant, supporting evidence of the exogeneity assumption.

Alternative explanations and the exclusion restriction assumption

Our identification assumes that only the emotional shock due to bereavement drives the difference between individuals’ immigration concerns, i.e., bereavement is a personal emotional event and does not directly or via other channels affect individuals’ attitudes towards the outgroup. As a parent’s death is likely to instigate all three negative emotions, our application of a single NE index can prove advantageous as it helps mitigate the possibility of multiple channels. Moreover, we also include factors that impact immigration concerns and may be correlated with the IV, a choice predominantly led by the existing research findings. Nevertheless, a concern needing careful discussion is that other potential effects of bereavement may influence individuals’ immigration concerns, which violates the exclusion restriction assumption, a necessary identifying assumption of the IV FE methodology. For example, bereavement may adversely (positively) affect an individual’s financial situation given high funeral costs (or incoming bequest). This changed financial situation may influence their immigration worries through changes in labor market circumstances and job security concerns. While the exclusion restriction assumption is not directly testable, using the richness of the SOEP data, we formally test whether the potential channels noted above possibly exist.Footnote 17

We apply FE regressions to test whether bereavement affects individuals’ labor market decisions. To do this, we regress the bereavement indicator on individuals’ likelihood of being out of the labor market (non-working). The results shown in column (1) of Table E-1 find that grief does not affect surviving children’s non-working status. After that, we restrict the sample to those active in the labor market and study whether bereavement predicts their decision to be unemployed. The results in column (2) show that bereavement does not induce unemployment among grieving. Column (3) investigates whether bereavement affects employed respondents’ worries about job security and provides no evidence of such an effect. These results conclude that bereavement does not affect individuals’ labor force status and worries about the labor market. After that, we study whether bereavement affects individuals’ household income and increases their financial concerns. The results presented in columns (4)–(5) show that the event of bereavement does not induce changes in the logarithm of monthly household income and does not increase individuals’ worries about their financial situation. In summary, while it is impossible to test all the potential channels that may violate the exclusion restriction assumption, our results indicate that alternative explanations noted above play a limited role. Nevertheless, in Sect. 5.4.3, we discuss the potential limitations of the IV strategy and present tests that allow the IV to be plausibly exogenous under certain conditions.

5 Results and discussion

5.1 Main results

5.1.1 OLS and FE estimates

The empirical investigation begins with a discussion of the correlation results. Table 2 presents the OLS and FE estimates of the relationship between individuals’ disparate negative emotions and immigration concerns. In panel A of the table, we show the results for the entire estimation sample after applying anger, fear, and sadness as continuous variables. In panels B and C, the estimates are shown separately for female and male subsamples. A broad reading of the results underscores the following observations. First, the OLS estimates indicate a positive and statistically significant association between negative emotions and immigration concerns. The positive association is almost identical across female and male subsamples. We do not observe any evidence of gender difference in the relationship.Footnote 18 Second, while the FE estimates also find supporting evidence of the positive relationship, a simple comparison of coefficients from OLS and FE models underlines the pertinence of person-fixed effects as necessary controls as they explain much of the association between negative emotions and immigration concerns.

We now test whether emotions share a long-term relationship with immigration concerns by replacing lagged (one-year) emotion measures in place of contemporaneous emotions in the estimated models. This accounts for the possibility that individuals’ emotional state from last year is correlated with their emotions this year (i.e., a potential case of serial correlation on observables) and is also associated with their immigration concerns. Table C-2 shows the OLS and FE estimates. OLS estimates are positive and statistically significant. However, it is possible that individuals who consistently reported more negative emotions had more immigration concerns, making it important to account for person-fixed effects. The FE estimates are statistically insignificant and are close to zero in most cases, supporting the relevance of individuals’ contemporaneous emotional state in explaining immigration concerns.

Additionally, in Table C-3 of Appendix C, we re-estimate the baseline specifications after applying anger, fear, and sadness as categorical variables. The estimates suggest that the higher frequencies of negative emotions are associated with more immigration concerns in most specifications. Interestingly, the positive association between immigration concerns and the frequency of anger is the strongest, which is in line with the findings of earlier research (see Erisen et al. 2020; Rico et al. 2017). Moreover, the association between immigration concerns and the frequency of feeling fearful is the weakest, especially among males (see column (4) of panel C). We also re-estimate the model with immigration concerns as binary and ordinal outcome variables using the Linear Probability, Probit, and Ordered Probit models. Tables D-1, D-2, and D-3 in Appendix D present the results and show findings that are qualitatively similar to the baseline results.

5.1.2 Negative emotions index (NE index)–baseline relationship

Given that individual negative emotions share a qualitatively similar relationship with immigration concerns, as noted above, we now study how the negative emotions index (NE index), constructed using the principal component analysis on the three individual negative emotions, relates to individuals’ immigration concerns. The NE index, henceforth constructed, shares a strong correlation with negative emotions used to build it, with a correlation coefficient of 0.816 with sadness, 0.799 with fear, and 0.711 with anger. The index not only helps simplify reporting our findings but, as will be seen later, it helps conduct IV estimation analysis by providing a single indicator of the three emotions. Each table hereon will report four coefficients for the NE index (d) and also separately for anger (a), fear (b), and sadness (c), respectively. Table 2 also reports the OLS and FE estimates of the relationship between the NE index and immigration concerns. A broad reading of the results suggests a consistently positive and statistically significant association between the NE index and immigration concerns. Also, the positive association is almost identical across female and male subsamples, an observation summarizing the findings in Sect. 5.1.1.

Additionally, columns (1)–(2) and (4)–(5) of Table C-4 in Appendix C report the results estimated using alternative negative emotion indexes motivated earlier (i.e., scale average and scale sum). These estimates are qualitatively similar to our baseline estimates, suggesting that the main results do not depend on the methodology used to construct the NE index.

As discussed in Sect. 2.2, we now consider the potential ambiguity in how sadness relates to immigration concerns, different from anger and fear. We do this by omitting sadness from the NE index and re-estimating the models using the new NE index. Table C-5 presents the results. Columns (1) and (2) present coefficients for the new NE index (PCA), which we conclude as qualitatively similar to those in Table 2. To be able to discuss the quantitative differences of coefficients for these two NE indexes, we also present the estimates of the new NE index created using scale average and scale sum methods. A quick overview of these results supports that these coefficients are comparable to those in Table C-4. In response, we conclude that sadness does not have a conceptually distinct relationship with immigration, and hereon, continue our analysis using the NE index generated using all the three available emotions.

5.2 Effect heterogeneity

Next, we investigate the effect heterogeneity due to respondent’s labor market status, birth cohorts, and the frequency of social media usage.

5.2.1 Labor force status

The existing research shows that the respondents’ labor market characteristics predict how they view international migration (Scheve and Slaughter 2001) and crucially influence how other predictors affect immigration concerns. For instance, Benesch et al. (2019) find that the media’s influence in determining immigration worries is particularly stronger among those not active in the workforce.Footnote 19 Subsequently, we test whether the effect of negative emotions on immigration concerns is distinct among working-age respondents (aged 17–65 years) with irregular and regular labor force status. To test this, we divided the sample into the respondents who were “always-working” during the sample period (i.e., regularly employed) and those “not always-working” (i.e., regularly employed, including those with non-working status). Columns (1) and (2) of Table 3 present the results of this exercise. We first discuss the association of NE index (d). The results show a positive correlation in most specifications. However, larger coefficient sizes are obtained for the irregularly employed than always-working individuals. A similar pattern of results is observed concerning anger and sadness, except the emotion of fear. The results report that the association of males’ frequency of experiencing fear is close to insignificance, but remains significant for females.

5.2.2 Cohort

Research consistently reports that older cohorts of natives are more opposed to immigration than younger cohorts. For instance, a negative association is found between age and support for immigration in all specifications of Hainmueller and Hiscox (2007) and in most specifications of Mayda (2006).Footnote 20 Subsequently, in columns (3)–(4) of Table 3, we estimate results separately for older and younger cohorts. We define respondents as older if they were born before 1970 (including the baby boomer generation), and others are denoted as younger. From the correlation analysis, we make the following observations. While FE estimates show a significant and positive association in most specifications, the results significantly differ between female and male subsamples. First, the effect sizes are, on average, larger among younger cohorts than older cohorts, an observation particularly true for males than females. Second, not all negative emotions are statistically significant in this subsample analysis, especially the male subsample. For instance, while all negative emotions predict immigration concerns among females, fear does not play any role among males. Moreover, increases in sadness are not associated with immigration concerns among old males.

5.2.3 Online social network

These days, a large portion of the population relies on social media for news consumption. Gottfried and Shearer (2016) show that 62% of US adults get their news from social media, as cited in Allcott and Gentzkow (2017, p.223). At the same time, however, social media websites are often blamed for the dispersion of fake news (Silverman, 2016, as cited in Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017), leading to political polarization (Bail et al. 2018). During the 2015 European refugee crisis, the political polarizing role of fake news was particularly evident. Research finds that a sizable portion of fake news was directed at refugees (Sängerlaub, 2017, as cited in Scott (2017)). For Germany, while traditional media coverage of the refugees was mostly positive (Haller 2017), the same cannot be said about social media. Müller and Schwarz (2021) find that the German far-right political party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) successfully used social media (Facebook) to generate and exploit anti-refugee sentiments by propagating hate speech and hate crimes in Germany. Therefore, we test whether the respondent’s access to online social networks intervenes in the causal relationship of interest.Footnote 21

In column (5) of Table 3, we present the estimates for individuals who use online social networks at least once per month on average, while column (6) shows the estimates for those who rarely or never use online social networks. Consistent with Boxell et al. (2017), we expect that individuals with less frequent use of the internet and social media show the largest increase in political polarization, depicting the increased role of emotions in predicting immigration concerns. While, in contrast to our expectation, the results in panel A do not suggest any differential associations for individuals’ frequency of social network use, the results in panels B and C hint at the gender differences in the associations studied. Notably, the results show that the emotions of fear and sadness play distinct roles. For instance, these two emotions play a statistically significant role in predicting immigration concerns among females who rarely use social media, while statistically insignificant associations observed among females with frequent social media usage. In contrast, fear and sadness play statistically significant roles only among males with regular use of social media. Such difference may arrive from the fact that males are more likely to use online social networks to get politics-related information than females, underlining social media’s differential role in manipulating and magnifying individuals’ emotional responses to immigration. As SOEP does not collect information on the content or type of social media usage, we suggest interpreting our findings cautiously. This concern is particularly relevant if occasional social media users consume content differently than frequent users.

Additionally, we suspect that there might be a correlation between cohorts and the frequency of social media use, compelling an alternative explanation of the findings above. We address this concern by further dividing the sample into the following four subcategories: (1) older cohorts often using online social networks, (2) older cohorts rarely using online social networks, (3) younger cohorts often using online social networks, and (4) younger cohorts rarely using online social networks. Estimation results are shown in Table C-7 in Appendix C. The finding that the heterogeneous cohort effects are primarily present among older females with less frequent access to social media underlines the moderating role of social media in the baseline effect. Moreover, the relationship between immigration concerns and negative emotions is more pronounced among younger males often using online social media. These results support our findings in Table 3.

5.3 Political outcomes

Now, we study whether the exogenous variation in citizens’ negative emotions has the potential to change the country’s political equilibrium.Footnote 22 We do this by analyzing whether negative emotions can determine individuals’ support for populist political parties, mainly anti-immigration far-right and often pro-immigration far-left political parties. Our separate consideration of far-right and far-left voting tendencies allows us to point at the origins of a rather broadly defined dependent variable, i.e., immigration concerns, which, as discussed earlier, can include pro- and anti-immigration considerations. To do this, we consider citizens’ self-reported support and intensity of support for populist parties as new outcomes and re-estimate the baseline models. For this analysis, we restrict the sample period to survey years 2013–2019 to coincide with the 2013 inception and rise of the most prominent German far-right political party (AfD). We construct a dummy variable far-right support indicating the individuals’ support of the notable far-right parties in Germany, such as AfD, die Rechte, Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands (NPD), Republikaner, or Deutsche Volksunion (DVU). To capture the intensity of political support, we employ another variable recording the intensity of their political support ranging between one (very seriously) and five (weakly). We re-scale these responses to generate the outcome variable with higher values indicating more intense support to the recorded political parties. Respondents who do not support the extreme right are assigned zero value. Similarly, we generate a dummy variable for supporting the far-left party in Germany, notably die Linke, and a variable for the intensity of support. The analysis excludes those who do not report supporting any political party and those with missing answers to survey questions.

Columns (1)–(4) of Table 4 report the results. The estimates in panel A show a positive correlation between the NE index and individuals’ support and the intensity of support for far-right parties. The results in panels B and C report that the association particularly holds for the male subsample, whereas no statistically significant associations are observed among females. Even among males, the association is statistically significant for the emotion of anger, whereas fear and sadness are not associated with individuals’ far-right political support. Notably, far-left support is virtually uncorrelated with the measures of negative emotions. The findings that negative emotions are positively associated with immigration concerns and influence far-right voting tendencies among German males may help highlight the importance of negative affect in explaining the recent rise of far-right politics.

5.4 IV FE estimates

5.4.1 IV FE results: main specification

Now we describe the findings of the IV strategy.Footnote 23 In contrast to the OLS and FE estimates, the result in panel A of column (3) in Table 5 shows that the average impact of the NE index on individuals’ immigration concerns is not statistically and significantly different from zero, providing evidence that the endogeneity concerns noted earlier are grounded. We propose two possible explanations to help understand the differences between IV FE estimates and the correlation results presented in Sect. 5.1.1. First, as discussed in Sect. 4.2, the possibility of increased negative emotions and simultaneous reduction in immigration concerns among natives after hearing of refugees’ plight provides one argument for the larger magnitude of the IV FE coefficients. The second possible explanation is that our IV estimates present the local average treatment effect (LATE), whereas the FE coefficients show the correlation over the entire population. Specifically, the IV estimates could be larger than the average treatment effect if the causal impact of NE index on immigration concerns is more considerable among individuals ever experiencing the death of a parent than those who never experienced it. For instance, older cohorts of respondents are more likely to experience the death of their parents than the younger population (see Sect. 5.2). Suppose the causal impact of negative emotions on immigration concerns is larger among older cohorts than in younger populations. In that case, the IV FE estimates are likely to be larger than the average treatment effect and coefficient found in the correlation analysis.

The estimates in panels B and C indicate gender-specific differences in the IV FE estimates. In particular, the results report that negative emotions affect immigration concerns among females but not among males. This finding is worth further discussion. To do so, we consider other channels through which negative emotions can instigate immigration concerns differently across genders. For example, we consider the role of individuals’ concerns towards international terrorism, crime, and job security. The existing research shows that these concerns more often carry over to determine individuals’ immigration concerns, e.g., international terrorism (Lerner et al. 2003; Bove and Böhmelt 2016; Helbling and Meierrieks 2020), crime (Valentova and Alieva 2014; Nunziata 2015), and fear of job loss (Dustmann and Preston 2007). Moreover, researchers have also found gender differences in emotional responses to these concerns. For example, Wadsworth et al. (2004) find males prefer emotional disengagement to terrorist threats, while females show emotion-based responses, such as emotional regulation and expression. Females are also likely to report more stress associated with their health and family than males (Folkman and Lazarus 1980). To this end, we expect that females may be more likely to worry about crime development in their neighborhood, which can be immigration-related, affecting their safety than males. Finally, Mauno and Kinnunen (2002) and Gimpelson and Oshchepkov (2012) show that females are more concerned about potential job loss than males. Regarding the research findings above, we investigate whether the gender differences in how emotions shape these concerns can help us explain the gender differences in the estimated results. To show this formally, we regress SOEP variables, capturing individuals’ concerns toward international terrorism, crime, and job security, on negative emotions. Table C-8 reports the results. While we find comparable OLS/FE coefficients for females and males on the relationship with concerns about terrorism and crime, the IV FE estimate of the effect of the NE index on terrorism is statistically significant for females but insignificant for males. No statistically significant impact of the NE index on crime development concerns is found. In contrast, the IV FE estimate of the effect on concerns about job security is weakly significant for males, but not for females. These results suggest that concerns about terrorism work as a channel between negative emotions and immigration concerns for females.

As already motivated in Sect. 4.2.2, we apply several robustness checks to the IV FE estimations. For a comprehensive discussion of this analysis, please see Appendix E. First, we test whether potential channels between the death of a parent and immigration concerns exist. For doing this, we regress potential channels on the IV using FE models (see Table E-1). Additionally, we test whether the predicted negative emotions correlate with the IV (see Table E-2). Third, we include more covariates to the regression model (see Table E-3) and exclude potential bad control variables from the model (see Table E-4), checking whether the main findings hold. Finally, we apply alternative definitions of the IV and focus on older individuals (see Table E-5). All results suggest the robustness of the main findings from the IV FE estimation.

5.4.2 Discussion of the magnitudes

To discuss the magnitude of the impact of negative emotions, we discuss the results estimated using alternative NE indexes. Columns (1)–(3) of Table C-4 present results estimated using the scale average method, while in columns (4)–(6), the estimation model employs the scale sum index. We first conclude that the table shows qualitatively similar findings to our IV FE results. The estimates in column (3) of panel B indicate that one standard deviation increase in scale average leads to an increase in female individuals’ immigration concerns by 0.1134 \((=0.793\times 0.143)\), about 5.63% of the sample mean (2.014). Similarly, the coefficients shown in column (5) suggest that one standard deviation increase of negative emotions among females increases their immigration concerns by 5.67% of the sample mean (\(=2.379\times 0.048/2.014\)).