Abstract

This study analyzed six legal forms of social enterprises (SEs) across four countries in terms of governance features to clarify trends to be highlighted. The research covered the topics of autonomy, representation/inclusion of stakeholders at the governing body level, membership and voting rights (not necessarily based on capital), and distribution constraints. The study presents two proposals to reconcile the US and European approaches to the governance of SEs: either define the governance patterns to be met to qualify as an SE and obtain any related advantages (under tax, public procurement, or any other law) or refute any organizational definition and treat the governing dimension of SEs as a supportive pillar of the social and economic dimensions instead of a stand-alone pillar.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The rise in popularity of the movement of doing business while achieving a social and economic impact, as part of the social entrepreneurship movement,Footnote 1 social innovation,Footnote 2 or business for good,Footnote 3 has contributed to enlarging the concept of social enterprises (SEs), adding another layer of complexity in the task of defining what an SE is. In reality, mapping SEs is like mapping the stars and constellations in the galaxy.Footnote 4

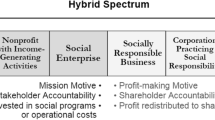

To draw the limits of this galaxy, scholars have suggested both organizational and sector-specific definitions. The arrival of business-oriented players in SEs has had a notable impact on organizational definitions, which are based on the European Commission’s three pillars of SEs: social, economic, and governance dimensions. The growing corporate social responsibility (CSR) requirements imposed on for-profit organizations have also challenged the theoretical basis for a distinction between for-profit and not-for-profit sectors.

The dimension of SE governance deserves more attention. Research has focused on the importance of balancing the economic and social dimensions of “dual” entitiesFootnote 5 or the involvement of stakeholders in decision-making.Footnote 6 An analysis of how the legislation and existing status have been drafted in that respect is relevant, given the scarcity in research on the implementation of the governance dimension.Footnote 7 Those performed from a legal perspective tend to be limited to the US/UKFootnote 8 or European approach,Footnote 9 without comparing the two.

The present work aimed to propose a legislative and regulatory analysis of the way in which the governance dimension is framed in common and continental law countries with respect to stakeholders’ inclusiveness and asset distribution. The goal is to elucidate whether approaches in common and continental law countries can be distinguished and whether distinctions may be reconciled for a way forward in the promotion of the SE movement. The countries selected for this comparative legal analysis are France, Italy, the United Kingdom, and the United States, for the following reasons. They are (1) countries with a broad approach to SEs, where SEs are not limited to the nonprofit sector but also include legal forms originating from the business sector, (2) countries with economic and political powers and abilities to influence future legislation, and (3) countries that can be considered as leaders in the innovation of SEs. This selection is also representative of the two legal national tendencies in favor of the institutionalization of SEs. France and Italy belong to the countries that have created one or more institutionalized legal forms and dedicated status, whereas the US belongs to the countries having created either a legal form or status.Footnote 10 This study focuses only on the legal forms. A similar study for dedicated statuses (e.g. the French société à mission or ESUS statuses or the Italian impresa sociale or società benefit statuses) would be of added value to complete the research. The legal comparison is thus limited to the following legal forms: the US low-profit limited liability company (L3C), benefit corporation,Footnote 11 UK community interest company (CIC) and community benefit society (CBS), French community interest cooperative (called société coopérative d’intérêt collectif (SCIC)), and Italian A-cooperative.

2 Governance Dimension in SEs: Theoretical Background

The concept of governance has evolved drastically over the past decade. Models of governance have been shaped along the distinction between for-profit and not-for-profit sectors. This distinction touches on the organizational structure of these entities. Meanwhile, the increase in CSR-related requirements for for-profit organizations has been a game changer.

2.1 Evolution of the Concept of Governance

The evolution of the concept of governance started as a check and balance administrative framework. Following various scandals in the private sector, notably Enron and WorldCom and the 2008 crisis, a new concept of good governance model has emerged to favor an equilibrium between the economic, societal, and environmental dimensions of the organization.

Within this perspective, the governance concept was thus defined as “the purposeful effort to guide, steer, control, or manage (sectors or facets) of societies,”Footnote 12 “the relationship among various participants in determining the direction and performance of corporations,”Footnote 13 or even “the holding of the balance between economic and social goals and between individual and communal goals.”Footnote 14 Put differently, governance is the framing of the exercise of power for the close alignment of the interests of individuals, corporations, and society, resulting in an economic necessity, political requirement, and moral imperative.Footnote 15 Governance thus opens the possibilities of a sustainable equilibrium between diversified and divergent interests.Footnote 16

This evolved notion of governance touches all sectors and organizations, even those far beyond the for-profit world.Footnote 17 Thus, it is also true for SEs, which blend economic and social goals.Footnote 18

2.2 Social Enterprise Governance Theories

Literature on SE governance identifies three main theories:Footnote 19

-

Stakeholder approach: within the stakeholder theory, an organization has responsibilities toward many stakeholders, beyond the shareholders.Footnote 20 Consequently, a governance structure should be modeled to determine appropriate stakeholder management. A stakeholder approach does not impose nor prevent stakeholder participation at the board level. Measurement processes are also of utmost importance to ensure appropriate and effective stakeholder management. Directors must be held accountable for their decisions, which should be made after the integration of stakeholders’ interests. Accountability is demanded by several stakeholder groups.Footnote 21 This may be achieved through inclusive and democratic board elections. Stakeholders’ interests may be integrated into the decision-making process either by representation at the board level or consultation (e.g., advisory board, interviews).

-

Stewardship approach: SEs are mainly viewed as stakeholder organizations.Footnote 22 They are described as organizations owned by the community as a wholeFootnote 23—that is, organizations whose assets are held in trust in the community.Footnote 24 The stewardship approach assumes that managers and directors are trustworthy and have a sincere intention to pursue the interests of the organization as a whole.Footnote 25 This relationship of trust provides the theoretical justification for any asset lock or distribution constraint rules,Footnote 26 as well as board composition. In this approach, inclusive representation at the governing body level is not necessary, given that the governing body carries “skills set that can more effectively manage the entire operation.”Footnote 27

-

Institutional approach: within this approach, the governance structure is aligned with the concepts of citizenship, participation, and legitimacy.Footnote 28 An organization is not an economy but rather an entity that is adaptable to social systems.Footnote 29 The structure becomes an echo of the expected social behavior. The institutional values of an organization influence the construction and maintenance of the same organization.Footnote 30 The constituent values provide the theoretical justification for any asset lock or distribution constraint rulesFootnote 31 as, within a legitimacy perspective, assets are used by those for whom the organization (here the SE) was created.Footnote 32 The same is true for board composition from the perspective of democratic value. From this perspective, the board should be modeled as a democratic participation tool.Footnote 33 The issue is no longer about a board made of persons elected for their competencies deciding, in a balanced way, how to allocate the profits, per the original stakeholder theoryFootnote 34 or stewardship theory.Footnote 35 The organizational structure echoes the democratic nature: the board is composed of representatives of the stakeholders, independent of their competence. With the same democratic aim, the assets are locked in to prevent shareholders from having a claim on them. As SuchmanFootnote 36 put it, organizational structure leads to organizational legitimacy.

2.3 CSR Paradigm and Theoretical Implications for SE Governance

CSR-related requirements represent a new paradigm in corporate governance. These CSR rules require a sustainable and community-oriented approach, which bears a direct impact on the governance process and board members’ fiduciary duties. The new CSR paradigm is both the fruit and seeds of a new approach to corporate governance, and CSR requirements have led to the integration of democratic governance features. Societal expectations must be integrated into managerial decisions. Societal interests are voiced during the decision-making process. The concepts of separation of powers, representation (notably, diversity), and transparency have been used to shape the new corporate governance model.Footnote 37 CSR-related requirements have thus brought a democratic dimension to corporate governance, as well as a proactive citizenship reality. The latter is mainly permitted through transparency and disclosure requirements. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors, namely, identification and impact measurement, impose a new form of mandatory stakeholder participation. Stakeholder implications arise not from a direct presence at the board level but from the board’s consultation processes (which are increasingly mandatory) as well as from stakeholders’ voices as investors, consumers, or cocontractors. Disclosure and transparency are supposed to render any organization responsive and allow citizens to engage in the governance process, so long as the data are understandable and comparable. Transparency is a means of citizen engagement and a component of stakeholders’ implication process. For instance, for the AA1000 standard, the leading methodology for sustainability-related assurance engagements, stakeholder involvement is performed by identifying, understanding, and responding to issues and concerns regarding sustainability as well as through reporting, explaining, and being available to answer to stakeholders concerning the entity’s decisions, actions, and performance.

The CSR paradigm and related concerns have helped reshape theories in favor of a major integration of stakeholders into the organization and into the decision-making process. This is true for business theories. The team production model of Blair and StoutFootnote 38 (as renewed), the coproduction model of Pestoff,Footnote 39 and Creating Shared Value of Porter and KramerFootnote 40 share a new partnership vision of society’s actors. This is also true at the state and institutional levels. These new corporate governance theories are aligned with the spread of network societyFootnote 41 and new public governance.Footnote 42 The cocreation and community-oriented approach has also been set as a priority goal at the global level with UN Agenda 2030 and SDG 17 dedicated to partnership. Thus, a form of democratic dimension has pervaded the corporate governance model through CSR. CSR requirements have, to a certain extent, transformed for-profit organizations into SEs.

The new CSR paradigm raises the question of what type of stakeholder participation is required to qualify as an SE. Is it stakeholders’ involvement or inclusion? Stakeholders’ inclusion is more than the process of involving stakeholders in decision-making. Stakeholders’ inclusion requires stakeholders to participate in identifying problems and contribute to the management of solutions in organizations. It consists of cooperation at all levels. The AA1000 standard suggests that an organization should establish a governance framework to achieve better results. The second related question is what kind of stakeholder empowerment is required to qualify as an SE. Stakeholder empowerment may result from the right to a voice based on the organization’s reported results, a voting right, and/or a presence at the governing body level (with or without voting rights).

2.4 Main Governance Challenges of SEs

The main governance challenges of SEs relate to (1) membership/stakeholder representation, (2) the balance between social and business goals and the related risk of mission drift, and (3) board recruitment.Footnote 43 SEs are a type of hybrid reality between traditional not-for-profit entities and traditional for-profit entities. This hybrid reality generates challenges, even as the CSR movement has made stakeholders’ representation a challenge for traditional for-profit entities.

The purpose of traditional business firms is to create value for their owners or shareholders. In contrast, the purpose of charitable organizations is to serve the public rather than private interests.Footnote 44 Given this difference in their purpose, accountability and success measurements are also different. Within business firms, accountability centers on financial performance, and within charitable organizations, on protecting the social mission—exercising care, loyalty, and obedience in serving the social purpose of the organization.Footnote 45 Success is defined in terms of progress toward the social mission, even if success measurement is complicated by a lack of common standards or benchmarks for social performance measurement, along with the general difficulty of comparing social performance across organizations.Footnote 46 This hybrid reality challenges the importance given to the social mission, be it in terms of inclusion of stakeholders (at the board level or in terms of voting rights) or in terms of the predominance of the social mission in case of misalignment of the two purposes. The board shall solve the dilemma of making a decision that could result in a high financial profit but low social profit and/or high social profit and low financial profit. This situation renders board recruitment a challenging task and raises the question of representation of stakeholders (notably in favor of the social mission) at the board level. On the merits, the dilemma remains a question of the predominance of one purpose in case of misalignment of the two. Table 1 summarizes the dilemma. The difference between an SE and a CSR-oriented enterprise is the predominance of the social purpose in case of conflicts.

2.5 Selected Governance Criteria

The main challenges of SEs are echoed by the following governance criteria within the approach of the EMES International Research Network, which supplement the three pillars of social, economic, and governance dimensions that support the ideal type of SEs proposed by the European Commission:Footnote 47

-

A high degree of autonomy (i.e., management independent of public authorities or other organizations): this is mainly relevant to organizations related to the state

-

A participatory nature, or involving persons affected by the activityFootnote 48

-

A decision-making process not based on capital: reference is usually made to the one member, one vote principle,Footnote 49 and

-

A limited profit distribution

Not everyone considers the last two criteria as governance criteria.Footnote 50 Some scholars treat these as social features.Footnote 51 The present study considered them as governance patterns. Governance is a tool that guarantees accountability and compliance with the purpose. It is also about balancing the interests of the organization’s stakeholders, which in turn guarantees accountability to all stakeholders. The decision-making process primarily helps balance the interests of the organization’s stakeholders, whereas the way profit is treated and restrictions on its use are shaped help determine the purpose of the organizations and limit the freedom of board members. Nonprofit charities are typically subject to legal prohibitions on distributing their profits and assets and are thus prevented from any form of equity financing or ownership that would compromise their public purpose for private gain.Footnote 52 Meanwhile, business organizations are characterized by important freedom in profit allocation. This freedom goes beyond profit allocation and covers asset allocation and dissolution distribution. The way these distribution constraints are managed and legally framed is thus of interest when distinguishing SEs from standard for-profit and not-for-profit entities. It is a matter of organizational governance that ensures the overall direction and accountability of the organization.Footnote 53

3 Governance Dimension in SEs: Legal Comparative Implementation

To compare the legal implementation of the SE governance dimension, this study focused on EMES criteria, considered here as governance features (see Sect. 2.3), with the following approach:

-

Autonomy is analyzed in terms of public authority participation.

-

Participatory nature is translated as the representation of stakeholders at the governing body level and if a reporting duty is imposed as a supplemental or additional means for securing stakeholders’ interests.

-

The decision-making process not based on capital is analyzed through the access, type of members, and voting rights under selected legal forms of SEs.

-

The limited profit distribution constraint lens is enlarged to cover any distribution constraint on profit, asset, and dissolution.

3.1 Autonomy

Among the analyzed SE legal forms, only the French SCIC provides for the participation of state and public authorities. That said, the French SCIC, inspired by the cooperative model, stipulates that public authorities, their groupings, and territorial public establishments may not hold more than 50% of the capital of each of the cooperative societies of collective interest.Footnote 54 Considering the limitations of this public participation, the French SCIC shall be viewed as an autonomous legal form. Regarding the UK CBS, Italian A-cooperative, US L3C, US benefit corporation, and UK CIC, all benefit from a high degree of autonomy.

3.2 Representation at Governing Body Level vs. Disclosure

In the SE laws under review, there is no legal requirement for the inclusion of stakeholders in the governing body. However, a reporting duty is typically imposed and includes an explanation as to how the SE’s purpose (or benefit to the community) is carried out. This does not apply to US L3C and UK CBS, as the former has no reporting duty and the latter, a limited one on returns and accounts (i.e., no report on how the benefit for the community is achieved). Table 2 summarizes the findings of the legal comparative analysis on these aspects of the democratic governance dimension of SEs.

3.2.1 L3C

L3C is not required to include noninvestor stakeholders at the governing body level. States do not require L3Cs to register and provide annual financial reports.Footnote 55

3.2.2 US Benefit Corporation

The board is responsible for ensuring that the dual purpose—the general and more specific public benefits—are pursued. There is no requirement for the representation of stakeholders at the board level.

All benefit corporations are required to create a benefit report to be made available to the public and assessed by a third-party standard (except in Delaware, where the release of the report to the public or the use of a third-party standard as an assessment tool is not mandatory). The standards for reporting and assessing the public benefit and positive impact are set by these independent third parties, such as B Lab and the Global Reporting Initiative.Footnote 56 There is no requirement for certifications or audits.

Some states require that a benefit director be designated to prepare the benefit report. This report will include the benefit director’s view on whether the corporation has successfully pursued its benefit.

3.2.3 UK CIC

A transparency requirement is imposed on CICs.Footnote 57 A CIC shall complete its annual report with a regulator, which makes it available for public scrutiny.Footnote 58 The director’s pay (aggregate and highest values), how the community benefit is achieved, how stakeholders are involved, the dividend paid, and any information on asset transfer must be reported.

The stakeholders’ involvement is part of the “community interest test” that is verified by the regulator. The latter may alter the board composition if they consider that the test is not fulfilled.Footnote 59 The stakeholders’ involvement requirement does not impose a representation at the board level. The involvement may be performed through meetings, consultations, advisory boards, committees, or online surveys. In sum, “CIC includes provisions for gathering stakeholder input towards community interest test, but there is no requirement for empowering stakeholders other than investors.”Footnote 60

3.2.4 Italian A-Cooperative

Since the end of 2017, all Italian cooperatives have had a board of directors composed of at least three directors elected for a maximum term of 3 years.Footnote 61 The deed of incorporation or bylaws may provide that one or more directors be chosen from the pool of members from the various categories of members. The appointment of one or more directors may be assigned by the articles of association or bylaws to third sector entities (ETS) or nonprofit ones, to civilly recognized religious entities, or to workers or users of the entity.

Since 2021, ETS, which include A-cooperatives, have been required to publish their social reportFootnote 62 based on certain guidelines.Footnote 63 The social report must be published on the institutional website of the organization and filed by June 30 of the following year with the Single Register of the Third Sector. The social report is conceived as a public document addressed to all stakeholders (from internal ones, such as workers or volunteers, donors, institutions, recipients of services, citizens of the territory in which the organization operates); it must provide useful information for the stakeholders to assess the extent to which the organization considers and pursues its objectives.

The guidelines identify the minimum content that each social report must contain. In brief, a social report of an A-cooperative must include the following:

-

General information on the organization: name, territorial area and field of activity, mission, relations with other organizations, and information on the reference context.

-

Governance information: data on the social base and direct and control bodies, aspects related to internal democracy and participation, and identification of stakeholders.

-

Information on people: consistent and detailed data on workers and volunteers, work contracts adopted, activities carried out, compensation structure (including data on pay differentials, documenting that the highest pay is not more than eight times higher than the lowest), and reimbursement methods for volunteers. Specific forms of disclosure are provided for compensation to directors and officers.

-

Information on activities: quantitative and qualitative information on the activities carried out, the direct and indirect recipients, and, as much as possible, the effects, indicating whether the planned objectives have been achieved and the factors that have facilitated or made it difficult to achieve them. This should include factors that threaten to undermine the organization’s goals and actions taken to counteract the same.

-

Economic and financial situation: data on resources separated by public and private sources, information on fundraising activities, any critical management issues, and actions taken to mitigate them.

-

Other information: litigation, environmental impact (if applicable), information on gender equality, respect for human rights, and prevention of corruption.

3.2.5 UK CBS

There is no requirement for the representation of stakeholders in the governing body. CBSs are listed on the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) website on the Mutuals Public Register. As such, they shall issue an annual report on returns and accounts. This report is not similar to a CIC benefit report: it does not include any information on how the community benefit is achieved or on financial aspects for the pursuit of the community benefit (except the highest interest rate paid on shares).

3.2.6 French SCIC

An SCIC is managed by one (or several) manager(s), who can be chosen either from among the members or from outside the SCIC. SCICs must include in their annual management report, in addition to the inventory and annual accounts, developments in the cooperative projects carried out by the company.Footnote 64 The report also serves the review that is conducted every 5 years by a qualified auditor of the SCIC cooperative management.

3.3 Membership and Voting Rights

French SCIC and Italian A-cooperative laws impose three different categories of membership. The voting rights in the decision-making process show a clear trend between the legal forms inspired by the cooperative form and the other legal forms inspired by for-profit ventures. UK CBSs, French SCICs, and Italian A-cooperatives apply the one person, one vote principle, whereas US L3Cs, US benefit corporations, and UK CICs have voting rights based on capital. Table 3 summarizes the findings of the legal comparative analysis on the membership and voting rights aspects, as democratic governance tools.

3.3.1 L3C

L3Cs offer the flexibility of tranche investing in three tranche categories. The equity tranche contains investors (notably, investors applying the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI)) accepting a low financial return while assuming a high risk to fund a specific social cause. Equity tranche investors give priority to creating a positive impact and take the risk of loss. These investors may be compared to venture capitalists or, more accurately, to venture philanthropists.

The mezzanine tranche includes investors accepting a low or even no financial return for doing social good. It offers modest financial returns. Dividends received by mezzanine tranche investors are below market rates.Footnote 65

The senior tranche contains investors seeking a market rate of return on their investment. This is made possible by a different risk allocation key, that is, between the three tranches and a greater assumption of financial risk by the other two tranches. The first tranche allows the L3C to attract investors in the next two tranches, which might otherwise find the social venture too risky.Footnote 66

In principle, voting rights are based on capital, without distinction between tranches. In practice, voting rights may differ as many L3C rules may be amended by membership agreements. A membership agreement may thus contain qualified voting rights, veto rights, and approval requirements in favor of investors of a certain tranche, especially the senior tranche.Footnote 67 Investors of the senior tranche may push to include in the membership agreement a right to be paid before the investors of the other two tranches.

3.3.2 US Benefit Corporation

The decision-making process of benefit corporations is based on capital. The decision-making process shall however fulfill the dual purpose, including thus the social mission. Stakeholders’ interests, such as those of communities, society and the environment shall be considered from the outset to identify the social mission that goeas hand in hand with the commercial purpose, to obtain the benefit corporation status.Footnote 68 For directors, the existence of a dual purpose for the company means that they have, under their duty of care, to consider the impacts of their decisions on a broader array of stakeholders rather than on only the interests of the shareholders. Board directors shall find a balance between the for-profit purpose and the public benefit purpose of the corporation.

3.3.3 UK CIC

Members of a CIC are shareholders who can elect or remove directors. Thus, voting rights are based on capital. Nonetheless, contrary to traditional private companies, CIC directors have the primary responsibility of implementing the social purpose of the company, monitored by its shareholders and regulatory authorities.

3.3.4 UK CBS

CBSs can issue share capital, provided the return to holders of shares is limited. This is comparable to the UK CIC. A CBS can issue withdrawable shares (up to GBP 100,000 per individual, with only a reasonable rate of coupons payable on that capital, with exceptions).Footnote 69 Thus, the holder of these shares may realize the value of the shares (which are not transferable, contrary to the shares of a typical for-profit company) by withdrawing the money held in their shares from the company. There are associated advantages (such as exemptions to regulated activity and financial promotion prohibitions under the Financial Services and Market Act 2000) and related restrictions (such as running a business of banking). Voting rights are exercised according to the one person, one vote principle, independent of the number of shares held by each person.

3.3.5 French SCIC

French law imposes three categories of members for a SCIC, each having a different relationship to the cooperative’s activities. This minimum triple category mandatorily includes the beneficiaries of the goods or services (e.g., customers, suppliers, inhabitants) and the employees of the SCIC (or, in the absence of employees, the producers of the goods or services). Membership is open to any natural or legal person under private or public law.Footnote 70

Members vote according to the one person, one vote principle. An SCIC may create (by inserting a specific provision in the bylaws) voting colleges to count the votes during the general assembly of SCIC members. Each voting college shall apply the one person, one vote principle, but the percentage allocated to each subtotal “voting college” may differ. The percentage may range between 10% and 50% of the votes in the general assembly.Footnote 71 The voting colleges should neither be a governance body nor be a part of the organization of an SCIC. The bylaws of an SCIC may also create specific shares with priority interest but without voting rights.Footnote 72

3.3.6 Italian A-Cooperative

A minimum of three members is required (a small cooperative has up to eight members).Footnote 73 Under the Italian Civil Code, cooperatives can create different categories of members. As a social cooperative, the Italian A-cooperative may have three kinds of members: (1) ordinary members participating in the mutualistic nature of the cooperative, (2) user members (unpaid), and (3) volunteers.Footnote 74 The number of volunteer members may not exceed 50% of the total number of members. The bylaws may also create other categories of investing (holders of assignable shares) and financing members (holders of participation shares).Footnote 75 As a matter of principle, Italian A-cooperatives adhere to the traditional one person, one vote principle.Footnote 76

However, an exception to this principle may be made for legal entity members.Footnote 77 Bylaws may attribute more votes in the assembly to certain members. In any event, voting capacity may not be increased to more than five votes per person. A person may not get more votes than the other remaining votes (e.g., if there are five members, including one legal entity, the legal entity may not have more than four votes attributed to it).Footnote 78

A further exception may also be allowed by the bylaws: i.e., in favor of cooperative members who achieve the mutualistic purpose through the integration of their respective enterprises.Footnote 79 In such cases, those benefitting from multiple votes may not use their votes for more than 10% of the total voting rights and not more than one-third of the present or represented voting rights.

3.4 Distribution Constraints

Laws regulations SEs impose asset and profit distribution constraints with various approaches. Their differences merit close scrutiny, and trends cannot be identified without taking a bird’s-eye view of such differences. From a schematic perspective, the country’s position on the globe seems to make a more significant difference in this debate compared with the relevant legal form. Put differently, SE legal forms resulting from a twisted version of a cooperative are not the only ones that can include asset distribution constraints, given the case of the UK CIC legal form.

This study identified US and European (from a geographical perspective) trends when it comes to asset distribution constraints. Table 4 gives the summary of the results of the legal analysis. All European SE laws under review impose an asset distribution constraint covering four aspects. Meanwhile, US legal forms do not restrict the use of assets and their transfer beyond the companies’ social purpose.

3.4.1 L3C

The regulation of L3Cs’ is based on the principles of self-regulation and self-financing. Therefore, there are no mandatory distribution constraints (whether on dividends, profits, or assets and whether at dissolution or at the time of transfer). Members are free to set constraints in the membership agreement.

3.4.2 US Benefit Corporation

There are no distribution constraints. Ebrahim, Battilana, and Mair concluded that “the strength of the benefit corporation legal status in enabling dual performance stands on its requirement that a company amend its charter to specify social and environmental interests.”Footnote 80

3.4.3 UK CIC

A CIC’s assets are regulated through a system called asset lock, which was put in place to ensure that the CIC uses its assets and profits for the community’s benefit. It gives reassurance to investors, who want to ensure that the CIC continues to run its business and social operations. Asset lock means that the CIC’s assets must be retained within the CIC to be used for the purposes for which the company was formed. If the assets are transferred out of the CIC, the transfer must satisfy one of the following requirements (to be included in the bylaws):

-

It is made at full market value so that the CIC retains the value of the assets transferred.

-

It is made to another asset-locked body (a CIC or charity, a registered society, or a non-UK-based equivalent) that is specified in the CIC’s bylaws.

-

It is made to another asset-locked body with the consent of the regulator.

-

It is made for the benefit of the community.

CICs can also adopt asset lock rules that impose more stringent requirements, provided they also include the basic provisions mentioned above. The prohibition for the CIC’s assets to be returned to its members, with the exception of the return of paid-up capital on liquidation and payment of dividends is part of the asset lock. According to statute, dividends may only be paid if they are authorized by the regulator. After the regulator approves a dividend payment, there are still three important restrictions:

-

The dividend may not exceed 5% of the Bank of England base lending rate of the paid-up value of a share.

-

The aggregate dividend cap is set at 35% of distributable profits.

-

Unused dividend capacity can only be carried forward for 5 years.

The dividend restrictions and asset lock indicate that investors are only given rights to limited dividends and are not given access to the full profits of the CIC.Footnote 81

3.4.4 UK CBS

CBSs may or may not adopt statutory asset locks.Footnote 82 If a statutory asset lock is adopted, it shall be unalterable.Footnote 83 If it is not adopted, the CBSs not adopting it are required by the FCA to have rules preventing the distribution of profits or assets to its members. The statutory asset lock of CBSs is similar to that of CICs. Assets shall be used for the CBSs’ purpose or, alternatively, for purposes that benefit the community. The transfer of assets is permitted only to other asset-locked bodies (namely, CBSs with restriction, CICs, charities, registered social landlords with restrictions on the use of assets, or equivalent bodies).Footnote 84 Payments to members are also prohibited, with the exception of the return of the value of the withdrawable share capital or the interest of such capital.Footnote 85 With regard to the interest on capital, there is no minimum guaranteed, and returns can be paid in cash or kind.

The withdrawal of withdrawable shares (which may not exceed GBP 100,000 per individual member)Footnote 86 is at the directors’ discretion, provided there is enough cash available. The value of the shares is fixed (par value) and not subject to speculation. In the case of liquidation or winding up, assets may be used to pay creditors, and the balance, if any, shall be distributed to qualified entities.

The statutory asset lock allows CBSs to qualify for a social investment tax relief. However, it does not allow conversion into a charitable CBS, whereas the voluntary asset lock does.

3.4.5 French SCIC

SCICs must allocate at least 50% of their profits to the statutory mandatory reserve (so-called development fund)Footnote 87 and a minimum of 15% of their profits to the mandatory reserve.Footnote 88 They must also allocate at least 57.50% of their profits to nonshareable reserves. This allocation can reach 100%. The remainder can be served in the form of annual interest to the shares, the rate of which is capped according to the average rate of return on private company bonds calculated over the 3 calendar years preceding the date of their general meeting, plus two points.

SCIC bylaws may create nonvoting priority interest shares. It is also possible to create redeemable profit-sharing securities (if an SCIC takes the form of a company by shares or a limited liability company) or cooperative investment certificates. The first are redeemable only in the event of the liquidation of the company or, at its initiative, at the end of a period not less than 7 years and under the conditions provided for in the contract of issueFootnote 89 (Cf. article 228-36 C. com). Cooperative investment certificates are nonvoting securities redeemable at the time of the liquidation of the cooperative and are remunerated in the same way as the interest on the shares.Footnote 90

Retained assets are to be distributed to qualified entities. When a member leaves the SCIC, they may obtain only the nominal value of its shares.

3.4.6 Italian A-Cooperative

For ETS, assets and any profits must be used exclusively for activities in pursuit of civic, mutualistic, and socially useful purposes.Footnote 91 As an exception to the prohibition of asset distribution, SEs, and thus Italian A-cooperatives (which are a specific group of ETS), can redistribute profits within certain limits. At least 50% of their profits shall be allocated to carry out their statutory activities or to increase their assets (this part is not subject to taxation). For SEs in the form of a company, this limited distribution of profits can occur:Footnote 92

-

In the form of revaluation or an increase in the shares paid by the shareholder in cases of free capital increase regulated by law. According to the regulations, the SE can allocate a quota of less than 50% of the annual profits and of the management surplus (after deducting eventual losses accrued in the previous years, to a free increase of the capital), within the limits of the variations in the annual general national index of consumer prices for families of workers and employees, calculated by the National Institute of Statistics for the period corresponding to that of the fiscal year in which the profits and management surplus were produced. In this case, the shareholder retains the right to reimbursement of the share thus increased.

-

In the form of a limited distribution of dividends to shareholders, including by means of a free share capital increase or the issue of financial instruments, which may not exceed the maximum interest rate on interest-bearing postal savings bonds, increased by two and a half points in relation to the capital paid up.

Moreover, SEs are allowed to allocate any profits and operating surpluses to purposes other than carrying out statutory activities or increasing assets. In particular, they can allocateFootnote 93 the following:

-

A share of less than 30% of the profits and of the annual management surplus (after deducting possible losses accrued in the previous financial years) to free donations in favor of ETS other than SEs, which are not founders, associates, partners of the SE, or companies controlled by it, aimed at promoting specific projects of social utility.

-

A share not exceeding 3% of the annual net profits (net of losses accrued in previous years) to funds for the promotion or development of SEs set up by the Fondazione Italia Sociale or other bodies. This share is specified as mandatory for social cooperatives (such as A-cooperatives).

In addition, social cooperatives may distribute transfers to members, provided that the methods and criteria for distribution are indicated in the articles of association or deed of incorporation. The distribution of transfers to members also needs to be proportional to the quantity or quality of mutual exchanges. A mutual management surplus must be ensured.

As for any ETS, the indirect distribution of profits and management surpluses, funds, and reserves to founders, associates, workers and collaborators, administrators, and other members of the social bodies is prohibited. This applies also in case of withdrawal from the company or individual dissolution. The following are deemed indirect distributions of profits:Footnote 94

-

1.

Payment to directors, auditors, and anyone who holds corporate offices of individual remuneration that is not proportional to the activity carried out, responsibilities assumed, and specific competences, or in any case higher than that envisaged in bodies operating in the same or similar sectors and conditions

-

2.

Payment to subordinate or self-employed workers of salaries or remuneration 40% higher than those provided for, for the same qualifications, by collective agreements, except in the case of proven requirements relating to the need to acquire specific skills for the purposes of carrying out activities of general interest, such as health care interventions and services, university and post-university training, and scientific research of particular social interest

-

3.

The purchase of goods or services for consideration that exceeds their normal value, without valid economic reasons

-

4.

The supply of goods and services, at conditions more favorable than market conditions, to members, associates or participants, founders, members of administrative and control bodies, those who work for the organization or are part of it in any capacity, individuals who make donations to the organization and their relatives within the third degree and relatives-in-law within the second degree, as well as companies directly or indirectly controlled or connected by them, exclusively on account of their position, unless such transfers or services do not constitute the object of the activity of general interest

-

5.

Payment to parties other than banks and authorized financial intermediaries of interest expense, in relation to loans of all types at four points above the annual reference rate. The aforementioned limit may be updated by the decree of the Minister of Labour and Social Policies, in agreement with the Minister of Economy and Finance

In the event of extinction or dissolution, the residual assets are devolved, subject to the positive opinion of the “competent structure” of the Single National Register of the Third Sector (RUNTS), and unless otherwise required by law, to other ETS in accordance with the provisions of the bylaws or a competent social body or, failing that, to the Fondazione Italia Sociale.Footnote 95 The deeds of devolution of residual assets carried out in the absence of or contrary to the RUNTS’s opinion are null and void.Footnote 96

4 Key Comments from the Legal Comparison

The key comments resulting from the comparative analysis of the governance structuration of the legal forms of SE under review are the following:

-

1.

From a very high-level perspective, the study identified US- and European-structured approaches to SEs. US legal forms do not entail distribution constraints, whereas European ones do. All legal forms under review have a stakeholders’ participation tool. However, contrary to US legal forms, in all European countries under review, SEs have a mandatory governance tool to secure stakeholders’ participation (see item 3 below).

-

2.

A closer look revealed no uniform patterns in membership and voting rights, representation in the governing body, and distribution constraints.

For instance, at the distribution constraint level, French SCIC law imposes that a maximum of 32.5% of all profits are redistributable, whereas with regard to UK CICs, dividends may reach a total maximum of 35% of the redistributable profits. For the UK CIC, unused amount may be carried forward for 4 years, allowing a reinvestment of earnings during the initial and maturity years and allowing larger dividends to be distributed in later years to shareholders.Footnote 97 This possibility does not exist in French SCICs and Italian A-cooperatives.

-

3.

No legal form under review directly mandates the inclusion of stakeholders at the governing body level. Stakeholders’ participation and empowerment go from mere involvement in the decision-making process to quasi-inclusion. Overall, US benefit corporations and UK CICs ensure stakeholder involvement during the decision-making process through consultation, notably when deciding how to pursue the community benefit purpose. UK CICs have a duty to report annually on how the benefit to the community was achieved, how stakeholders were involved, and which dividend payments or asset transfers occurred. Stakeholders’ participation goes a step further in UK CBSs, with the decision-making process not based on capital. That being said, stakeholder involvement is a democratic participation tool emptied of its substance in the absence of a full information report that would allow members to identify problems and exercise their vote as active citizens. Therefore, the UK CBS probably achieves stakeholder involvement rather than stakeholder inclusion. French and Italian cooperatives are the forms that come closest to stakeholder inclusion. They achieve indirect stakeholder inclusion at the governing body level, given that they impose three categories of members who vote at the general assembly and elect the governing body.

-

4.

The reporting duty is considered by legislators as a governance tool and a stakeholder involvement tool. It allows the organization to be accountable and the stakeholders to be provided with all necessary information to use their voice. This is seen as a participation and legitimacy tool. However, the style and content of the report vary across countries, undermining its potential to be a proper stakeholder involvement tool. The key aspects are the report’s availability, precision, comparability, and associated legal liabilities in case of misrepresentation or omission. These were the shortfalls noted in the implementation of the EU Directive 2014/95 on reporting nonfinancial information. In April 2021, the European Commission issued a first draft of the new CSR Directive with the aim of creating a European standard on which all reports will be based, to ease their comparison. There is no reason for the critiques of the CSR reports under the EU Directive 2014/95 to be inapplicable to social reports under SE laws, given that social reports are governed by different legal regulations.

-

5.

The differences in the implementation of stakeholder involvement reveal the difference in theoretical choice between the United States and Europe. “European” forms tend to reflect the stewardship theory, whereas US forms reflect the stakeholder theory. In the European legal forms of the SEs under review, namely, French SCICs, Italian A-cooperatives, and UK CICs and CBSs, there is no need for a representation of stakeholders at the governing body level, owing to the trust given to managers, who genuinely pursue the ultimate social mission of the organization. This trust, along with the management orientation, is reflected in the distribution constraints. In the US legal forms under review, stakeholders involvement occur through a consultation that is considered de facto mandatory owing to the dual purpose/social mission of the organization and the director’s related liability. This is in line with the traditional approach to stakeholder theory. In this sense, US L3Cs and benefit corporation adhere to the principle of freedom of organization espoused by the stakeholder governance theory.

5 Possible Options for SE Governance Patterns

The comparative study reveals the absence of uniform governance patterns. This is particularly true for stakeholders’ participation and empowerment, which goes from (mere) consultation to what is close to inclusion at all levels of the organization. In view of this, two options seem possible, with drastic consequences on the possibilities to bring together all legal forms under an umbrella, and ultimately within an SE model law:

-

1.

Define the governance patterns to be met to qualify as an SE and exclude from the definition of an SE all entities that do not meet these criteria. Under this option, all legal forms under review cannot be brought together under the same umbrella.

In terms of autonomy, this option entails defining the percentage of voting rights and/or representation at the board level (in relative terms) of public authorities. In any case, the percentage should be set below 50%.

In terms of stakeholder participation and empowerment, this option entails defining the required type of stakeholder involvement (involvement through consultation, advisory board, or inclusion at the governing body level with voting rights). In this respect, a clear distinction from CSR-related requirements is necessary. In other words, stakeholders’ participation must go beyond mere consultation, made indirectly mandatory through the managers’ duties of care and diligence. The following possibilities can be envisaged, alone or together:

-

Provide for the implementation of an advisory stakeholder’s board that the governing body will have to consult, mandatorily, before every important decision.

-

Attribute one or more seats in the governing body to the representative(s) of major stakeholders.

-

Mandate an annual consultation of stakeholders on the program and planning of next year’s commercial activities.

-

Provide important stakeholders with a veto right on governing body decisions.

-

Subject the report on stakeholders’ participation to the auditing of a central authority, with the publication of both the report and the authority’s opinion on the website of this authority.

With regard to the decision-making process, the legislator should decide whether a democratic principle (one person, one vote) is to be recommended, imposed, or abandoned. Knowledge and expertise have more to give than mere representations. A clear allocation of responsibility would be preferable. Instead of focusing on the power to be attributed to the assembly and the way to cast votes, the right of the general assembly to revoke the board members should be canceled, while the duties of care and loyalty of the board members should be ensured to converge toward the social mission. These will further limit the power of the capital holder in an SE. Therefore, the primary responsibility of a UK CIC of fulfilling a social purpose needs to be imitated. A priority amongst the purposes in favor of the social mission, in case of misalignment of the purposes, is more appropriate. An ideal scenario is to give stakeholders the right to sue members of the governing body for liability. This right of stakeholders to sue members of the governing body may derive from laws imposing reporting duties and prohibiting misleading information.

-

In terms of distribution constraints, the legislator should define whether such constraints are required and, if so, to what extent. The difficulty with SEs arises in the case of conflict of purposes, when the for-profit and social purposes are not aligned or not equally achieved. The difference between an SE and a CSR-oriented enterprise is the predominance of a social purpose in case of conflicts. To some extent, profit distribution constraints may help solve this conflict. A dissolution allocation constraint as well as a transfer of asset constraint should be imposed. Other profit and asset distribution constraints may be avoided if there is a mandatory hierarchy clause on the predominance of social purposes in case of conflict of purposes.

-

2.

Reevaluate governance patterns as a tool for framing social means. The governance dimension of SEs may be adopted as a supportive pillar for the other two (social and economic dimensions) rather than as a separate founding pillar. This allows for the regrouping of all kinds of SEs under the same umbrella, including all the legal forms under review. In other words, the idea is to adhere to the social innovation school of thought when defining SEs rather than adopt the democratic governance and participatory nature of EMES. This approach implies that the governance dimension of SEs should not be seen as a stand-alone pillar (as suggested by the European Commission) but rather as supportive of the social and economic dimensions. This may not be inconsistent with the organizational theory as it allows for different organizational and governance structural mechanisms, so long as they support a positive social impact mission and then legitimize it. Any form of stakeholders’ involvement and empowerment, even though it does not reach the degree of inclusion at all organizational levels, may be considered as sufficient so long as social innovation is achieved. Social innovation may result from new services, a new quality of services, new methods of production, new production factors, new forms of organization or collaboration/participation, or new markets.

The governance mechanism will then adapt to social innovation and reflect the peculiarities of the latter. Schmitz’s opinionFootnote 98 merits espousal: innovation will most probably be social at the input, means/processes, output, and outcomes levels. At the process level, innovation will imply stakeholders’ involvement (and not necessarily inclusion) to achieve the “working together” suggested by MulganFootnote 99 and Johnson.Footnote 100 When assessing the output and outcomes levels, a regular reporting duty appears to be necessary, as well as a participatory tool and source of legitimacy toward the community. The necessity of mandatory distribution constraints would no longer hold interest, and the decision-making process not based on capital may take other forms than the one person, one vote principle, with different rights attributed to stakeholders depending on their importance in achieving the social innovation.

The advantage of option 2 is that it embraces all legal forms and types of SEs and does not risk weakening the movement. The social entrepreneurship movement will then not be considered a separate movement. Difficulties will remain in trying to grasp the concept of innovation within a legal framework or in defining which entity decides (e.g., public authority, market), and according to which criteria and timeline, to allow a project to reach maturity without resulting in a deficient project.

Option 1 has the advantage of offering a way to define SEs in organizational terms, with governance patterns. The forms linked to the social entrepreneurship movement (such as benefit corporations) may not be qualified as SEs unless it is renouced to the stakeholder’s inclusion and distribution constraints. However, an organizational definition may justify the advantages and incentives. Option 1 may be used to draft an SE status instead of a new legal form. This way would be favourable to the social entrepreneurship movement and those other actors closer to the for-profit world and its mentality. Promotion may then take the form of a public support and incentives, competition laws tolerance, easier access to public procurement (reserved contracts), increase of points in a public procurement competition and even to tax advantages (either for the entity itself or for investors).

6 Conclusion

The present analysis found no common denominator in terms of governance structure that would allow the legal forms of SEs to be grouped under the same umbrella or an SE model law. Even at the European level, there is no uniformity in the governance patterns of the legal forms of SEs.

These distinctions in patterns explain the failure of the attempt to define SEs in organizational terms and the difficulty in conceptualizing instruments to promote the movement from an organizational perspective. The way stakeholders’ participation is envisaged by each legal form is symptomatic of the inconsistency of the movement in governance terms. Such participation varies from consultation to quasi-inclusion at the governing body level. This diversity does not help promote the SE movement from a tax perspective. Thus, legal forms closer to not-for-profit organizations are treated like charities, whereas other forms are treated as pure for-profit entities.

Thus, this research identified two options: either define the governance patterns to be met to qualify as an SE and obtain any related advantages (whether under tax, public procurement, or other laws) or avoid an organizational definition and instead consider the governing dimension of SEs as a supportive pillar for the social and economic dimensions. As legal forms of SEs continue to multiply, a decision has to be made to avoid staying in a legal and conceptual limbo that is not favorable for the promotion of SEs. Pursuing the first option is highly recommended. That being said, a similar study on SE statuses would complete the research and help identify the legal forms to keep and those to abandon in favour of a legal status.

Notes

- 1.

The concepts of “social entrepreneurship” and “social entrepreneur” do not refer to an organization but rather to an approach. If the aim is to drive positive social change, individuals with this mindset do not necessarily want to adhere to the economic dimension of SEs.

- 2.

Social innovations refer to new ideas that meet social needs, create social relationships, and form new collaborations.

- 3.

Business for Good refers to a movement with a certain vision of the economy and its mission. The moral mission is that of a more sustainable economy. It captures enterprises that do not have a distribution constraint.

- 4.

Defourny et al. (2021), p. 6.

- 5.

- 6.

- 7.

- 8.

Ebrahim et al. (2014).

- 9.

Del Gesso (2020).

- 10.

Countries having renounced the creation of any legal form or status are thus not represented but are worth mentioning as an existing category to evince the possibility of growth of the SE movement.

- 11.

Social Purpose Corporations and the Californian Flexible Purpose Corporation are not mentioned as they are less strict versions of benefit corporations in terms of social purpose and social contribution.

- 12.

Kooiman (1993), p. 2.

- 13.

Monks and Minow (1995), p. 1.

- 14.

Cadbury (2003), p. VI.

- 15.

Charkham (1994), p. 366.

- 16.

Neri-Castracane (2016), p. 45.

- 17.

Low (2006), p. 376.

- 18.

Borzaga and Defourny (2001), p. 350.

- 19.

Mason et al. (2006).

- 20.

- 21.

Sternberg (1997).

- 22.

Low (2006), p. 379.

- 23.

Pearce and Hopkins (2013), p. 284.

- 24.

Dunn and Riley (2004), p. 633.

- 25.

Davis et al. (1997), pp. 24–25.

- 26.

Dunn and Riley (2004), p. 645.

- 27.

Mason et al. (2006), p. 290.

- 28.

Parkinson (2003).

- 29.

Mason et al. (2006), pp. 291–292.

- 30.

- 31.

Dunn and Riley 2004, p. 645.

- 32.

Mason et al. (2006), p. 295.

- 33.

Low (2006), p. 378.

- 34.

Freeman (1984).

- 35.

Donaldson and Davis (1991).

- 36.

Suchman (1995), p. 571.

- 37.

Gomez and Korine (2005), p. 741.

- 38.

Blair and Stout (1999).

- 39.

Pestoff (2012).

- 40.

Porter and Kramer (2011).

- 41.

Hartley (2005).

- 42.

- 43.

- 44.

- 45.

- 46.

Ebrahim and Rangan (2014).

- 47.

The three pillars of the European Commission have a total of nine criteria.

- 48.

Defourny and Nyssens (2012), p. 14.

- 49.

Ibid., pp. 14–15.

- 50.

Of this opinion, Gleerup et al. (2019), p. 5.

- 51.

For instance, Defourny and Nyssens (2012), p. 14 described the limited profit distribution as a social criterion.

- 52.

- 53.

Cornforth (2014), p. 2.

- 54.

Ibid.

- 55.

Pearce and Hopkins (2013).

- 56.

- 57.

The Community Interest Company Regulations 2005, Section 26.

- 58.

Companies (Audit, Investigations and Community Enterprise) Act 2004, Section 34(2).

- 59.

Ebrahim et al. (2014), p. 92.

- 60.

Ibid.

- 61.

Legge n. 205/2017 (art. 2542 Codice civile).

- 62.

Decreto legislativo 112/2017, Art. 9(2).

- 63.

Decreto del 4 luglio 2019.

- 64.

Décret n° 2015-1381 du 29 octobre 2015° 47-1775. Art 19 terdeceies.

- 65.

- 66.

Pearce and Hopkins (2013), p. 279.

- 67.

Ibid.

- 68.

Eldar (2014), p. 186.

- 69.

Cooperative and Community Benefit Societies Act 2014, Section 24.

- 70.

Loi n° 47-1775 du 10 septembre 1947 portant statut de la coopération. Art 19 septies.

- 71.

Ibid. Art. 19 octies.

- 72.

Ibid., Art. 11 bis.

- 73.

Legge n. 266/1997, Art. 21.

- 74.

Ibid.. Art. 2.

- 75.

Legge n. 59/1992, Art. 4 and 5.

- 76.

Codice Civile, Art. 2538 para. 2.

- 77.

Ibid., Art. 2538 para. 3.

- 78.

Mosconi (2019), p. 4.

- 79.

Codice Civile, Art. 2538 para. 4.

- 80.

Ebrahim et al. (2014), p. 86.

- 81.

Pearce and Hopkins (2013), p. 286.

- 82.

Co-operative and Community Benefit Societies Act 2014, Section 29 to be read with The Community Benefit Societies (Restriction on Use of Assets) Regulations 2006.

- 83.

The Community Benefit Societies (Restriction on Use of Assets) Regulations 2006, Part. 3 (7).

- 84.

Ibid., Part. 2(3) and Part 3(6)(b).

- 85.

Ibid., Part. 3 (6) (a).

- 86.

Co-operative and Community Benefit Societies Act 2014, Section 24.

- 87.

Loi n° 47-1775 du 10 septembre 1947 portant statut de la coopération, Art 19 nonies.

- 88.

Ibid., Art 16.

- 89.

Code de commerce, Art. 228-36 C.

- 90.

Loi n° 47-1775 du 10 septembre 1947 portant statut de la coopération. Art 19 sexdecies to 19 dovicies.

- 91.

Decreto 112/2017, Art. 3 para. 1.

- 92.

Ibid., Art. 3 para. 3.

- 93.

Codice Civile, Art. 2545 quarter.

- 94.

Decreto 112/2017, Art. 3 para. 2.

- 95.

Codice del Terzo Settore, Art. 9.

- 96.

Ibid.

- 97.

The Community Interest Company Regulations 2005, Section 20.

- 98.

Schmitz (2015), p. 36.

- 99.

Mulgan (2012).

- 100.

Johnson (2010).

References

Berger P, Lukmann T (1966) The social construction of reality. Penguin, London

Blair M, Stout LA (1999) A team production theory of corporate law. Virginia Law Rev 85(2)

Borzaga C, Defourny J (2001) The emergence of social enterprise. Routledge, London

Brakman Reiser D (2010) Governing and financing blended enterprises. Brooklyn Law School, Legal Studies Paper No. 183

Brakman Reiser D (2011) Benefit corporations-sustainable form for organization? Wake Forest Law Rev 46:591–625

Cadbury A (2003) Corporate governance: a framework for implementation. In: The World Bank (eds) Corporate governance and development, global corporate governance forum, Foreword

Charkham J (1994) Keeping good company: a study of corporate governance in five countries. Clarendon, Oxford

Chisolm LB (1995) Accountability of nonprofit organizations and those who control them: the legal framework. Nonprofit Manag Leadersh 6:141–156

Cornforth C (2014) Nonprofit governance research. The need for innovative perspectives and approaches. In: Cornforth C, Brown WA (eds) Nonprofit governance: innovative perspectives and approaches. Routledge, London

Davis JH, Schoorman FD, Donaldson L (1997) Towards a stewardship theory of management. Acad Manag Rev 22:20–47

Defourny J, Nyssens M (2012) The EMES approach of social enterprise in a comparative perspective. WP no. 12/03, 2012

Defourny J, Nyssens M (2017) Fundamentals for an international typology of social enterprise models. Voluntas: Int J Volunt Nonprofit Org 28:2469–2497

Defourny J, Mihaly M, Nyssens M, Adam S (2021) Introduction - documenting, theorising, mapping and testing the plurality of SE models in Central and Eastern Europe. In: Defourny J, Nyssens M (eds) Social enterprise in Central and Eastern Europe, theory, models and practice. Routledge, New York

Del Gesso C (2020) An entrepreneurial identity for social enterprise across the institutional approaches: from mission to accountability toward sustainable societal development. Int J Bus Manag 15(1)

Diochon MC (2010) Governance, entrepreneurship and effectiveness: exploring the link. Soc Enterp J 6(2):93–109

Doherty B, Haugh H, Lyon F (2014) Social enterprises as hybrid organizations: a review and research agenda. Int J Manag Rev 16(4)

Donaldson T, Davis JH (1991) Stewardship theory or agency theory? CEO governance and shareholder returns. Aust J Manag 16:49–65

Donaldson T, Preston LE (1995) The stakeholder theory of the corporation: concepts, evidence and implications. Acad Manag Rev 20:65–91

Dunn A, Riley CA (2004) Supporting the not-for-profit sector: the government’s review of charitable and social enterprise. Mod Law Rev 67(4):632–657

Ebrahim A, Battilan J, Mair J (2014) The governance of social enterprises: mission drift and accountability challenges in hybrid organizations. Res Organ Behav 34:81–100

Ebrahim A, Rangan VK (2014) What impact? A framework for measuring the scale and scope of social performance. Calif Manag Rev 56:118–141

Eldar O (2014) The role of social enterprise and hybrid organizations. Yale Law & Economics Research Paper No. 485

Fazzi L (2012) Social enterprises, models of governance and the production of welfare services. Public Manag Rev 14(3):359–376

Fishman JJ (2003) Improving charitable accountability. Maryland Law Rev 62:218–287

Freeman RE (1984) Strategic management: a stakeholder approach. Pitman, Boston

Freeman RE, Reed DL (1983) Stockholders and stakeholders: a new perspective on corporate governance. Calif Manag Rev 25:88–106

Fremont-Smith MR (2004) Governing nonprofit organizations: federal and state law and regulation, paperback

Gleerup J, Hulgard L, Teasdale S (2019) Action research and participatory democracy in social enterprise. Soc Enterp J 16(1):46–59

Gomez PY, Korine H (2005) Democracy and the evolution of corporate governance. Corp Gov 13(6):739–752

Hansmann H (2000) The ownership of enterprise. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Hartley J (2005) Innovation in governance and public services: past and present. Public Money Manag 25:27–34

Johnson S (2010) Where good ideas come from: the seven patterns of innovation. Penguin, London

Kooiman J (1993) Modern governance: new government-society interactions. Sage, London

Kopel M, Marini M (2016) Organization and governance in social economy enterprises: an introduction. Ann Public Cooperative Econ 87(3):309–313

Low C (2006) A framework for the governance of social enterprise. Int J Soc Econ 33(5/6):376–385

Mason C, Kirkbride J, Byrde D (2006) From stakeholders to institutions: the changing face of social enterprise governance theory. Manag Decis 45(2):284–301

Monks R, Minow N (1995) Corporate governance. Blackwell, New York

Mosconi R (2019) I diritti amministrativi dei soci cooperatori di cooperativa: il diritto di voto in assemblea. Cooperative e dintorni n. 23/2019

Mulgan G (2012) The theoretical foundations of social innovation. In: Nicholls A, Murdoch A (eds) Social innovation-blurring boundaries to reconfigure markets. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, pp 33–65

Neri-Castracane G (2016) Les règles de gouvernance comme moyen de promotion de la responsabilité sociale de l’entreprise- réflexions sur le droit suisse dans une perspective internationale. Schulthess, Zurich

Osborne SP (2006) The new public governance? Public Manag Rev 8:377–387

Osborne SP (2009) Delivering public services: time for a new theory? Public Manag Rev 12(1):1–10

Olson J (2011) Two new corporate forms to advance social benefits in California, The Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance and Financial Regulation. https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2011/11/17/two-new-corporate-forms-to-advance-social-benefits-in-california/

Parkinson J (2003) Models of the company and the employment relationship. Br J Ind Relat 41:481–509

Pearce JA, Hopkins JP (2013) Regulation of L3Cs for social entrepreneurship: a prerequisite to increased utilization. Nebraska Law Rev 92:259–431

Pestoff V (2012) Co-production and third sector social services in Europe: some concepts and evidence. Voluntas: Int J Volunt Nonprofit Org 23:1102–1118

Pestoff V, Hulgard L (2016) Participatory governance in social enterprise. Voluntas: Int J Volunt Nonprofit Org 27:1742–1759

Porter ME, Kramer MR (2011) Creating shared value. Harvard Business Review, Cambridge

Sacchetti S, Birchall J (2018) The comparative advantages of single and multi-stakeholder cooperatives: reflections for a research agenda. J Entrep Organ Divers 7(2):87–100

Schmitz B (2015) Social entrepreneurship, social innovation, and social mission organizations: toward a conceptualization. In: Cnaan R, Vinokur-Kaplan D (eds) Cases in innovative nonprofits: organizations that make a difference. Sage, London, pp 17–42

Silverman D (1971) The theory of organisations: a sociological framework. Basic Books, New York

Sternberg E (1997) The defects of stakeholder theory. Corp Gov 5:1–10

Spear R, Cornforth C, Aiken M (2007) For love and money: governance and social enterprise. National Council for Voluntary Organisations, UK. http://oro.open.ac.uk/10328/

Suchman M (1995) Managing legitimacy: strategic and institutional approaches. Acad Manag Rev 20:571–611

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Materials

Materials

-

Community Benefit Societies (Restriction on Use of Assets) Regulations 2016

-

Co-Operative and Community Benefit Societies Act 2014

-

Companies (Audit, Investigations and Community Enterprise) Act 2004

-

The Community Interest Company Regulations 2005.

-

Loi n° 47-1775 du 10 septembre 1947 portant statut de la coopération

-

Loi n°2001-624 du 17 juillet 2001, portant diverses réformes d’ordre social, éducatif et culturel

-

Loi n° 47-1775 du 10 septembre 1947 portant statut de la coopération

-

Décret n°2002-241 du 21 février 2002 relatif à la société coopérative d’intérêt collectif

-

Code de commerce

-

Decreto legislativo 112/2017 (Decreto legislativo 3 luglio 2017, n. 112- Revisione della disciplina in materia di imprese sociale (a norma dell’articolo 1, comma 2, lettera c) della legge 6 giugno 2016 n. 106

-

Decreto legislativo 3 luglio 2017, n. 117 “Codice del Terzo settore”

-

Decreto 4 luglio 2019 Adozione delle Linee guida per la redazione del bilancio sociale degli enti del Terzo settore.

-

Legge 381/1991 (Legge 8 novembre 1991, n. 381) (Disciplina delle cooperative sociali)

-

Decreto Legge 34/2019 (Dl Crescita): art. 43 comma 4 bis

-

Codice civile

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Neri-Castracane, G. (2023). The Governance Patterns of Social Enterprises. In: Peter, H., Vargas Vasserot, C., Alcalde Silva, J. (eds) The International Handbook of Social Enterprise Law . Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14216-1_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14216-1_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-14215-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-14216-1

eBook Packages: Law and CriminologyLaw and Criminology (R0)