Abstract

In this chapter, we draw on positive developmental psychology, psychology of religion and spirituality, and developmental neuroscience to explore how youth religiousness and spirituality contribute to thriving through the process of meaning-making. Thriving involves the individual, relational, and aspirational development necessary to pursue a life purpose that is meaningful to the self and one’s surroundings. Meaning-making is the process of constructing and internalizing abstract beliefs (about oneself, the world, and one’s priorities) into salient values that contribute to the moral development necessary to thrive. When youth consider abstract ideas in the context of their actions, transcendent emotions, and the broader world, then their meaning-making can result in values-based goals and behaviors. Adolescents are naturally motivated to explore identity-related issues of meaning, values, roles, and belonging. In particular, meaning-making occurs when youth are given the opportunity to reflect in an enriching dialogue with caring adults. In more ways than most youth contexts, religion and spirituality provide young people with opportunities to seek and form meaning by being prompted to process transcendent beliefs and emotions through the narratives, intergenerational relationships, and transcendent experiences that religion and spirituality often provide.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

A burgeoning body of research reveals the many ways religion and spirituality (hereafter, R/S) contribute to the positive development of youth (Hardy et al., 2019; King & Boyatzis, 2015; Schnitker et al., 2019). With increasing awareness of the importance of promoting trajectories of human thriving that contribute to flourishing societies, scholars are looking for approaches to thriving that include not only individual well-being and life satisfaction but also a beyond-the-self orientation and actions that strengthen the surrounding systems. One such approach, the reciprocating self, orients human development towards a telos (i.e., ultimate goal) that furthers an ongoing, mutually beneficial fit between self and society and requires continual individual, relational, and aspirational development (King & Mangan, in press). Although research affirms the importance of moral ideals and spiritual commitments in this process (King et al., 2020; Schnitker et al., 2019), little is understood about how youths’ beliefs turn from ideas into lived action. Meaning-making may be one helpful explanation (Furrow et al., 2004; Immordino-Yang et al., 2019; see Park & Van Tongeren, Chap. 6, this volume). Synthesizing brain development research in this area, we explain how meaning-making is the process of constructing and internalizing salient beliefs into a youth’s narrative identity and core values. In turn, these values guide prosocial behaviors that are a mechanism and marker of thriving.

It is already well-documented that a person’s narrative identity helps incorporate their beliefs and values into goals that motivate prosocial and purposeful behaviors indicative of thriving. Narrative identity is the evolving story that “people have in their minds about how they have come to be the particular people they are becoming” (McAdams, 2021, p. 122). One’s narrative identity integrates a reconstruction of their past and imagined projection of their future into a single narrative arc, which provides a sense of unity, purpose, and temporal coherence. Building on the work of McAdams, Schnitker (Schnitker et al., 2019; Ratchford et al., Chap. 4, this volume) and King (King et al., 2020) have proposed the term transcendent narrative identity to designate narrative identities that offer a beyond-the-self context for someone’s life, providing a unifying spiritual, religious, or moral purpose to their narrative identity. What is less well-documented or explained is how transcendent beliefs are incorporated into one’s narrative identity. Therefore, the focus of this chapter is to explain how R/S facilitate the process of youth meaning-making through exposure to transcendent beliefs and emotions in the context of caring relationships. The convergence of ideological, social, and transcendent resources promotes thriving, as reciprocating selves develop and grow personally and relationally, including the moral and spiritual commitments required to contribute meaningfully beyond the self.

In this chapter, we draw on research from positive psychology, positive youth development, developmental neuroscience, and the psychology of R/S to describe how youth are poised for constructing meaning that leads to enduring, values-aligned goals. These goals motivate behaviors that enable youth to become fulfilled, contributing members of society. Our interdisciplinary approach highlights how biological influences (e.g., brain maturation) coalesce with religious and spiritual development to create and sustain meaning. Our overall goal is to explain why youth have a propensity to engage in meaning-making and how R/S have the potential to provide the coherent belief systems, caring relationships, and transcendent experiences that lead to transcendent narrative identity and emotions and thereby to purposeful, thriving adults.

Background: Relational Developmental Systems Theory and Thriving

To describe how religious and spiritual development co-act with child and adolescent brain development and promote thriving through meaning-making, we draw on the relational developmental systems (RDS) metatheory. RDS considers the breadth of human development, including religious and spiritual development, in the context of the diverse systems in which humans live (King et al., 2021; Lerner, 2018; Overton, 2015; Davis et al., Chap. 18, this volume). Human development occurs not only through the bidirectional interactions between an individual and the world around them. It also occurs at all levels of the developing system—from the cellular to the social to the perceived transcendent. For instance, human cognitive abilities (e.g., our imagination) and attachment patterns (shaped by our relationships with our parents) influence our religious/spiritual development, such as how we view and relate to the divine. RDS emphasizes the multifaceted nature of religious/spiritual development, including the roles of the neurological changes that emerge with expanding cognitive and social-emotional skills. For example, the ability to take another person’s perspective (or imagine God’s perspective) and feel empathy for another, are reasoning and emotional processing capacities that enable young people to engage in more abstract ideas and feelings of transcendence. Additionally, capacities like these help youth become involved in diverse and deeper relationships, which in turn nurture young people’s meaning-making processes and capacities.

RDS is predicated on the worldviews of relationalism and holism, which emphasize the interconnectivity of all things. For instance, the well-being of one people group has direct or indirect effects on other people groups. Consequently, thriving aims for the entire developmental system to flourish over time (King & Mangan, in press; Overton, 2015). At a practical level, this suggests that youth thriving involves contributions beyond-the-self—whether to one’s family, peer group, community, the environment, or the greater good (Lerner, 2018). Although many conceptualizations of flourishing, well-being, and happiness within positive psychology emphasize the individual, from an RDS perspective, thriving involves ongoing mutually beneficial relationships between individuals and their contexts (see Davis et al., Chap. 18, this volume). To emphasize this, we draw on the theoretical telos of a reciprocating self (Balswick et al., 2016; King & Mangan, in press), which infers that the purpose of human development is to grow as differentiated authentic individuals who are in mutually beneficial interdependence with others. This process requires ongoing moral and spiritual development that sustains a good fit between individuals and their broader contexts (King & Mangan, in press; Lerner et al., 2003; Schnitker et al., 2019). This theory highlights how a developing person increases their capacity to thrive through individual, relational, and aspirational growth over time (see Appendix 17.S1, Fig. 17.S1). Aspirational refers to the evolving moral ideals and spiritual commitments that guide and motivate contributions to the greater good through changing circumstances and contexts. To summarize, to thrive is to develop and adapt in authentic, mutually beneficial relationships that nurture one’s contextually adaptive values, purpose, and contributions. Given that purpose involves an enduring goal that is meaningful to the self and makes a valuable contribution to the greater good (Damon et al., 2003), continually clarifying what is meaningful and of value to oneself and one’s surroundings is essential for identifying and pursuing purpose.

To illustrate this dynamic process of thriving through individual, relational, and aspirational development in the pursuit of an enduring life goal that is meaningful to self and society, consider a transgender youth raised in an Orthodox Jewish community. This young person may struggle to feel seen and loved for who they are (individual), may struggle to feel close and respected by their religious community (relational), and may experience limited opportunities to pursue their faith in their current context (aspirational). Given such a potential discord, this young person will need to sort through their beliefs, their relationships, and their understanding of God in order to determine what is most important and of value, especially as they navigate issues of gender and religious identity. In short, and hopefully with the assistance of caring adults, they will sort through what is meaningful and their sources of meaning in order to navigate a good fit between who they are both as a transgender person and as someone who is religiously committed to Judaism. This process may lead them to a Reformed synagogue or other Jewish community that not only is more supportive of this transgender young person’s uniqueness but also allows more opportunities for them to pursue their sense of life purpose and contribute meaningfully to their religious community. For this young person to thrive, their personal strengths and social world need to align to support a mutually beneficial relationship, where the young person can reciprocate—receive and give—among the people they live with. R/S provide rich opportunities (and at times challenges as described above) for the meaning-making necessary for this young person to cultivate an ongoing good fit between themselves and the social world in which they are embedded, as they develop and thrive more fully as reciprocating selves.

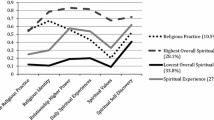

Religious and Spiritual Development

From an RDS perspective, religious and spiritual development are distinct but overlapping constructs. They each occur as an individual interacts with the micro- and macro-systems around them, including beliefs, relationships, and perceptions of transcendence. Religiousness involves engaging in the doctrines, community, and rituals of a religious tradition. Religious development, however, is specifically the changes in one’s capacity to engage in the beliefs, relationships, and practices associated with religion (King & Boyatzis, 2015). Spirituality, on the other hand, refers to one’s experience of and response to transcendence (King et al., 2020). Transcendence—whether experiencing God or another form of ultimate reality—involves our thoughts, emotions, and other senses. Transcendence requires individuals to connect their perceptions with broader macrosystem-level beliefs in a way that encourages complex social emotions such as admiration, compassion, and moral elevation. For instance, youth might experience transcendence when they feel a connection with others or God while singing in a worship service, when they are confronted by natural beauty, or when they are volunteering. Transcendent ideas and emotions can inspire devotion to beliefs, resulting in the integration of values and life goals with personal identity, resulting in fidelity, which in turn motivates values-aligned behaviors of contribution that are characteristic of thriving (Appendix 17.S1, Fig. 17.S2; King et al., 2014; Lerner et al., 2003; Riveros & Immordino-Yang, 2021).

In contrast to many definitions of spirituality that emphasize an individual’s search or experience of transcendence (which can sometimes result in overlooking changes in identity and behaviors), our theoretical approach is referred to as reciprocating spirituality. Reciprocating spirituality emphasizes the bidirectional influence between the individual and the transcendent, which results in structural changes in the individual and leads to transcendent, values-aligned identity and behavior. For example, ideas and feelings about transcendence may result in a transcendent narrative identity informed by being a part of a reality bigger than daily life, and it may inspire devotion to act accordingly. Thus, spiritual development refers to the changes in one’s capacities to experience transcendence in a way that informs identity and worldview and motivates values-aligned behavior (King et al., 2014, 2020).

From this perspective, both religious and spiritual development occur through the developing young person’s interactions with the world (see Davis et al., Chap. 18, this volume). Religion provides a context ripe with a set of beliefs, practices, and community that usually promote transcendence and spiritual development. However, spiritual development may or may not occur within the context of religion. Because spiritual development requires transcendence, it involves the engagement of transcendent beliefs and emotions that are often shared in relationships and pursued through practices. Thus, religious and spiritual contexts each include ideological, social, and transcendent milieus that provide beliefs and narratives, transcendent emotions, and relationships that support meaning-making (King et al., 2020).

Meaning-Making

Meaning-making is central to spirituality. It represents the process of constructing and internalizing cognitive and affective experiences of transcendence as enduring beliefs, which are incorporated into one’s narrative identity. For the purposes of this paper on youth R/S and thriving, meaning-making refers to the process of internalizing beliefs into one’s transcendent narrative identity. These salient beliefs inform people’s views of themselves in relationship to the world, forming values-aligned goals that guide their actions accordingly (Furrow et al., 2004). Park’s (2010) Meaning Making Model addresses how people assimilate adversity into their meaning system or accommodate the meaning system to adversity (see Park & Van Tongeren, Chap. 6, this volume). For example, this adversity-based assimilation and accommodation is usually referenced with regard to spiritual coping, wherein individuals draw on their religious and/or spiritual beliefs, communities, and practices as strategies for making meaning out of loss, death, and struggle. However, within this chapter, we address the relationship between meaning-making and spirituality beyond the context of coping in order to understand how meaning-making incorporates beliefs into narrative identity and results in values-based goals that are necessary for the purposeful pursuits that help youth thrive.

For youth, meaning-making does not occur exclusively in contexts of R/S, but it is more broadly recognized as the process of identifying beliefs that are of enduring salience to an individual. These ideals are then incorporated into one’s narrative identity, serving to motivate and guide behavior accordingly. Such enduring and meaningful thoughts and their accompanying moral emotions are ascribed motivational properties and serve as values (Merrill & Fivush, 2016). When a belief is meaningful, the experience of salience generates fidelity to it and signifies its integration into one’s narrative identity. This then motivates actions consistent with one’s ideals (Erikson, 1968; Furrow et al., 2004; King et al., 2014). For instance, an experience of Allah through an answered prayer may generate further devotion to Allah and motivate commitment to living out one’s Muslim beliefs. Fidelity to a belief system involves a commitment to act on those beliefs and has the propensity to develop values-aligned goals that underlie the pursuit of noble purposes. Consequently, spirituality is seminal to thriving because the cognitive and emotional stimulation of transcendence spurs on an other-oriented meaning-making process that results in fidelity, informs a transcendent narrative identity, values-aligned goals, and purposeful behaviors (Erikson, 1968; Lerner et al., 2003; King et al., 2020). In Appendix 17.S1, Figs. 17.S3 and 17.S4 illustrate the thriving process and portray the cycle of religious/spiritual contexts prompting meaning-making, which leads to values that are informed by one’s transcendent narrative identity and to embodied feelings that guide and motivate pursuit of purpose. Purposeful activities then engage people deeper in the beliefs, relationships, and experiences of transcendence, which further supports the process of thriving. As such, meaning-making is a critical task of spiritual and religious development in youth. Understanding the brain growth that takes place across later childhood and adolescence gives insight into the timeliness of seeking belonging, connection, and meaning, which all are central to spirituality and thriving.

Brain Readiness: Minds and Meaning-Making

Developmental neuroscience explains how the child and adolescent brain is equipped for and nurtured through the process of making-meaning that is necessary for thriving. The following section overviews the interplay between youths’ brain development and social support in relation to meaning-making. Broadly speaking, although meaning-making can promote brain and psychosocial development, it also is shaped by brain development, as well as by opportunities for guided reflection in the context of caring and nurturing relationships.

To illustrate, imagine the socially distanced birthday of a 4-year-old girl. Family and friends have brought or mailed their gifts. Some relatives are on a video call as she opens gifts. She excitedly jumps with every toy she unwraps, politely thanking the giver. Next, she opens the box that her aunt sent: knitted mittens. She is caught by surprise as she was expecting another toy. She sees her aunt’s and parents’ faces, and understands that a reaction is expected from her; however, she does not know how to respond. Her parents understand her reaction and say: “Oh, she wants you to keep your hands warm this winter, doesn’t she?” “Yes, I guess so,” she replies, still surprised. “It feels good to receive mittens then, right? It means your aunt cares for you very much,” says her mom. “Oh yeah, I think so,” she says, smiling and a bit more convinced.

What these parents did was as mundane as powerful. Throughout this brief exchange, they helped their daughter build meaning by connecting an unexpected gift with its more abstract, underlying significance. The parents could have merely focused on her behavior (“say ‘thanks’ to your aunt”). Instead, they guided her through a pattern of thinking that promotes the experience of social emotions such as gratitude, as well as prosocial behaviors in response.

Building Age-Appropriate Narratives

In the process of meaning-making, children and adolescents build narratives—stories they tell themselves—that connect life events with their beliefs and values. A youth’s meaning-making is influenced by their developmental stage (Merrill & Fivush, 2016), particularly by their abilities to engage in abstract thinking and experience social emotions. Adults can be supportive of children’s and adolescents’ abstract meaning-making by providing opportunities for reflection and guidance (Immordino-Yang et al., 2019). The newly developing abstract patterns of thinking and feeling may in turn promote neural and mental growth (Riveros & Immordino-Yang, 2021).

Building abstract life narratives promotes healthy psychosocial development. Life narratives are thought to be organized into more encompassing master narratives about who we are and aspire to be (McAdams, 2021). Abstract narrative meaning-making therefore helps nurture values-oriented thinking and organizes youths’ transcendent narrative identity (Merrill & Fivush, 2016). It motivates actions and purposes (McAdams, 2021), as future goals connect with personal values and ideally become intrinsically meaningful over time.

Among the many ways in which life narratives and meaning-making are practiced, a particularly well-suited medium for meaning-making can be found in warm, safe, social relations that afford opportunities for practice (Merrill & Fivush, 2016). When children and adolescents share narratives with close others, they can elaborate on experienced or imagined events, while the listener can help scaffold, edit, and inspire more abstract interpretation of those events (Palacios et al., 2015). As the capacities for abstract thinking are still maturing during childhood and adolescence, adults’ guidance can be fundamental (Immordino-Yang et al., 2019). Conversations with valued and trusted adults can expose children and adolescents to a more values-based, wiser lens of interpreting life events (Grossmann et al., 2010) and can inspire abstract and contextually adaptive meaning-making that allows youth to navigate changing circumstances purposely.

Child and Adolescent Brain Development

From year 3 onwards, children’s capacities for meaning-making start developing from a flexible yet concrete mindset, focused on what is physically observable (Gopnik et al., 2017). Progressively, children’s increasing knowledge about others’ emotions and psychological state enrich their interpretations (Nelson et al., 2013). Children’s proclivities for meaning-making become more abstract and values-oriented as their cognitive and social-emotional skills increase (Immordino-Yang et al., 2019). Thus, the progressive advancement in children’s meaning-making is likely to be undergirded by their brain development (Krogsrud et al., 2016).

After the relatively upward trajectory of children’s neural and psychological growth, adolescence becomes an inflection point. Initiated by hormonal changes in puberty, adolescents’ brains start a “dual” trajectory of development (Suleiman & Dahl, 2017). On the one hand, there is significant growth in brain areas located underneath the cortex, such as the basal ganglia, which are critically involved in basic motivations (Telzer et al., 2018). Research has found that an injury in the basal ganglia may leave a youth feeling purposeless (Riveros et al., 2019). The initial growth of the basal ganglia is paralleled by an abrupt onset of adolescents’ susceptibility towards social and identity-relevant rewards (Suleiman & Dahl, 2017). This provides adolescents with motivation to explore new roles and environments while building values congruent with their identity (Fuligni, 2019). On the other hand, adolescents experience significant growth in multimodal cortical brain areas, and these areas integrate complex cognitive and emotional information, support abstract meaning-making, and facilitate the experience of complex social emotions such as compassion and admiration (Immordino-Yang et al., 2019).

In short, developmental proclivities to process happenings, motivations, and emotions in terms of their broader meaning enable children and adolescents to embed concrete, context-specific perceptions and actions into abstract narratives that transcend the here-and-now. These proclivities change following region-specific and nonlinear brain developmental trajectories, even as they are also being influenced by social–relational opportunities for connecting reflections with beliefs and values about who adolescents are and aspire to be (Riveros & Immordino-Yang, 2021). The adolescent’s brain is biologically tuned to cognitive and social–emotional opportunities for meaning-making (Pfeifer & Peake, 2012). Opportunities for abstract meaning-making, therefore, have an outsized effect on adolescents’ neurobiological growth (Larsen & Luna, 2018). Those opportunities, when properly guided by a trusted adult, can have a favorable impact on adolescents’ development (Immordino-Yang et al., 2019). Attuned adults are well-positioned to scaffold youth in constructing values and emotion-rich representations of perceptions and actions, thus forming the stage upon which youth can meaningfully engage with R/S.

Religion and Spirituality as Meaning-Making Milieu

R/S have the potential to maximize this critical period of brain development for thriving. As youth mature, they are increasingly biologically oriented to opportunities for building meaning and processing identity-related information. In the following section, we explain how the meaning-making necessary for thriving can occur through the abstract belief systems, transcendent emotions, and caring relationships available through R/S.

Abstract Beliefs

Religious and spiritual contexts spur the contemplation of abstract ideas, which encourage youth meaning-making. Specifically, beliefs that address issues of identity, belonging, and meaning are especially stimulating for maturing youth. As their cognitive capacities increase, they are naturally enticed to consider immaterial and supernatural notions of God or the divine, contemplate existential questions such as issues of life and death, and reflect on their lives in the context of their broader community and world. The brain’s development during adolescence helps youth experience abstract reflection as rewarding and stimulating, meeting a maturing young person’s needs for clarifying identity and purpose (Pfeifer & Peake, 2012).

Congregations and youth groups are fruitful environments for the discussion of abstract ideas, helping youth create meaning that contributes to their identity. Furthermore, religion offers a coherent ideological belief and value system, which can readily function as a master narrative through which young people can identify, organize, and internalize abstract beliefs (Syed et al., 2020). More often recognized as a resource for adolescent identity, narratives are also important for the construction of childhood self-concept (King & Boyatzis, 2015; Morris et al., 2011; Syed et al., 2020). Master narratives facilitate internalization of beliefs in a coherent and effective manner, as opposed to a system of unrelated abstract beliefs. In turn, these master narratives lend significance to personal narratives. When youth locate their personal narrative identities within grander religious or spiritual narratives, their own personal stories are “sanctified” and take on even deeper significance as transcendent narrative identities (King et al., 2020; Ratchford et al., Chap. 4, this volume; Schnitker et al., 2019; Syed et al., 2020).

In an increasingly globalized world, youth are frequently exposed to many belief systems, and the cacophony of values and expectations can be overwhelming. Although other contexts such as families, schools, and clubs have implicit values and beliefs, settings that intentionally articulate and promote moral beliefs through active engagement and reflection are rare (for exceptions, see Larson et al., 2020). However, when youth are given the opportunity to engage with these types of abstract ideas and values, thriving may occur. Because thriving involves attitudes and actions that benefit others, the moral beliefs and caring relationships that are usually characteristic of R/S offer opportunities for constructing meaning that can inform youths’ values-aligned goals that motivate prosocial behaviors. For example, Catholic students who participate in community service within their Jesuit school and process their service in the context of the life and actions of Jesus Christ may adopt a religious rationale and motivation for their actions. Religious beliefs that address issues of justice, the environment, and human dignity and diversity are particularly salient to adolescents, enabling them to make sense of the world and their place in it. Thriving occurs when moral beliefs and emotions are incorporated into the young person’s narrative identity and motivate values-aligned behaviors.

Self-Transcendent Emotions

One way to enhance transcendent beliefs, and therefore increase meaning-making, may be through feeling more self-transcendent emotions. Youth who experience self-transcendent positive emotions are more likely to behave prosocially, a key characteristic of thriving (Yaden et al., 2017). Broaden-and-build theory indicates that positive emotions open our minds, making us more receptive to new ideas and better at solving issues creatively. This helps us build new resources and skills that give us opportunities to experience even more positive emotions, build even more skills, and so on (Fredrickson, 2001). One category of positive emotions, known as self-transcendent positive emotions, also includes an awareness and feeling of oneness with other people; this includes emotions such as awe, compassion, love, joy, elevation, and gratitude (Yaden et al., 2017). Feeling self-transcendent emotions decreases self-focus, increases connectedness to others, and fosters altruistic thinking and prosocial behavior (Yaden et al., 2017). These emotions are even associated with a decrease in materialism and envy, as well as lower rates of depression and higher academic achievement (Froh et al., 2011).

Religious and spiritual contexts encourage self-transcendent emotions (see Van Cappellen et al., Chap. 20, this volume). Many programs, organizations, and institutions (e.g., political parties, scouting) offer rich social environments and ideologies, but few promote experiences of transcendence, where people perceive and experience a reality beyond themselves (King et al., 2014; Yaden et al., 2021). Religious and spiritual contexts often do this naturally. For instance, people who pray more feel more gratitude (Lambert et al., 2009) and awe, which increase religious and spiritual feelings and behaviors (van Cappellen & Saroglou, 2012).

In addition, religious and spiritual practices offer effective means of experiencing self-transcendent emotions. Engaging in practices such as prayer or meditation provides youth an opportunity to experience spiritual, self-transcendent connection with nature and with divine beings or entities (King et al., 2014; Yaden et al., 2021). For example, Eastern traditions often emphasize the growing awareness of an essential unity of all beings and the universe. Many expressions of R/S provide conduits for self-transcendent emotions that can help internalize abstract beliefs into salient commitments that motivate values-based goals conducive to thriving.

Caring Relationships

Furthermore, R/S provide relationships that support meaning-making through dialogue, modeling, and opportunities for young people to be a part of something beyond themselves. R/S are particularly effective in generating social capital and offering spaces for explicit conversations that support youths’ reflections and integration of beliefs and values (Fasoli, 2020; Hardy et al., 2019; King & Boyatzis, 2015; Larson et al., 2020). Generally, religious traditions have specific processes for mentoring their young, usually involving various forms of teaching, socialization, and connection. For example, within the Hindu religion, gurus are considered to be self-realized masters and often viewed as embodiments of the divine. In some forms of Judaism, sages are important role models of right living and wisdom. In the Christian tradition, youth are often discipled by youth pastors or adult church volunteers.

Intentional mentoring can provide not only specific teaching but also caring relationships that scaffold the process of meaning-making through dialogue (Fasoli, 2020; Merrill & Fivush, 2016). Within caring relationships, adults can actively reflect and discuss moral ideals, the practicalities of living them out, and their implications for the broader world. For instance, in the example above with the 4-year-old girl receiving birthday gifts, the adult explicitly connected the positive feelings of receiving a gift and the behavior of saying thank you with the belief that thanking someone is a good thing to do because relationships are valued. The parent scaffolded the meaning-making process by connecting the child’s emotions and behaviors with a belief that has the potential to be internalized as a value for the child. Young people often learn beliefs and internalize values when others help them make connections between their current behaviors and prospective beliefs. Religious communities can also offer youth opportunities to lead and serve. Dialogue in which adults openly connect the youth’s behaviors with moral and societal implications can demonstrate how abstract beliefs can be lived out for the benefit of others.

In addition, religious communities provide living and historic examples of how abstract beliefs can be enacted (Erikson, 1968; King & Boyatzis, 2015; King et al., 2020). Adults can be formative sources of inspiration by being explicit about how their beliefs motivate their actions. For example, adults can explain how their own values helped them overcome challenges and can discuss both the positive and negative emotions and experiences that accompany living out one’s convictions. As such, religious communities can provide an important social context with caring adults, where moral ideals can be explored, exemplified, and then embodied by youth.

Unique to R/S is the possibility of experiencing a caring perceived relationship with divine beings or entities. Youths’ perceived relationships with divine beings can be an important relational developmental system that impacts their meaning-making and sense of identity, while also motivating values-aligned behaviors conducive to thriving. Even adolescents who have had poor attachment relationships with their caregivers will oftentimes develop a security-enhancing perceived attachment relationship with God during adolescence. That surrogate attachment relationship can help them with moral meaning-making and guide and motivate thriving.

Implications for Clinical and Religious Practitioners

The research synthesized here indicates multiple application ideas for clinical and religious practitioners. Specifically, practitioners can provide opportunities for youth to talk about abstract ideas, such as hosting discussion groups or book clubs. Additionally, practitioners can provide opportunities for youth to experience transcendent emotions such as awe, gratitude, and elevation. For instance, awe can be induced by having youth spend time in nature, interact with big ideas (e.g., God), or just look at pictures of inspiring scenery and discuss their beauty (Passmore & Holder, 2016).Footnote 1 Adults can enhance this experience by helping youth connect their thoughts and emotions to their growing ideas of their own identity, life goals, and place in the broader world. For example, many youths aspire to be vegetarian. From the approach put forth in this chapter, dietary commitments tend to be less enduring unless they become internalized by reflecting on how an individual’s behavior may impact the world around them. When beliefs and behaviors become an integrated part of a larger master narrative, they take on more significance (Syed et al., 2020). In addition, when abstract ideals, such as “it’s bad to eat meat,” are connected to actual behaviors (e.g., not eating meat) that have implications for the broader world, youth experience rewarding emotions and thus are more apt to internalize such beliefs as values.

Practitioners can also connect youth to spiritual guides. Spiritual mentoring is an example of a caring relationship in which youth learn about transcendent ideas, practice abstract meaning-making, experience social emotions, and observe inspiring role models. For instance, religious and spiritual settings provide many resources that offer the opportunity for youth to reflect on transcendent ideas. These ideas could emerge from sacred texts, spiritual writings, and individual and communal practices and then be explored in dialogue with a caring adult. In this way, spiritual mentoring can influence adolescents’ thoughts, emotions, and general well-being. Adult relationships are key to supporting youth as they try to make sense of the ordinary and extraordinary in life. Mental health professionals, educators, and other practitioners can support youth development by directing them towards engaging in the religious/spiritual communities in their lives. Although congregations and religious youth groups are usual options, racial/ethnic communities and extended families should also be considered as resources for spiritual mentors, beliefs, and practices. For future directions in this area, see Table 17.S1 in Appendix 17.S1.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we aimed to explain the link between meaning-making, R/S, and thriving in youth development. Synthesizing existing research, we suggest that spirituality is seminal to thriving because the cognitive and emotional stimulation of transcendence spurs on other-oriented meaning-making that results in a transcendent narrative identity, values-aligned goals, and prosocial behaviors necessary for thriving. Whereas adolescents are increasingly motivated to engage with the kinds of abstract ideas, transcendent emotions, and caring relationships that are suited for meaning-making, children also benefit from more relational scaffolding that can help them internalize values. R/S not only provide these socio-affectively rich opportunities to construct meaning and internalize values, but they generally also offer beyond-the-self beliefs and norms. The research reviewed in this chapter is intended to aid both researchers and practitioners in encouraging meaning-making as a way to promote positive spiritual and religious development and thriving.

Notes

- 1.

For more ideas about activities youth can do to evoke self-transcendent emotions such as awe and gratitude, see Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center website: https://ggia.berkeley.edu/

References

Balswick, J. O., King, P. E., & Reimer, K. S. (2016). The reciprocating self: Human development in theological perspective. InterVarsity Press.

Damon, W., Menon, J., & Bronk, K. C. (2003). The development of purpose during adolescence. Applied Developmental Science, 7(3), 119–128.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. W. W. Norton.

Fasoli, A. D. (2020). Conversations and moral development. In L. A. Jensen (Ed.), Oxford handbook of moral development (pp. 482–500). Oxford University Press.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

Froh, J. J., Emmons, R. A., Card, N. A., Bono, G., & Wilson, J. A. (2011). Gratitude and the reduced costs of materialism in adolescents. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12(2), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-010-9195-9

Fuligni, A. J. (2019). The need to contribute during adolescence. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(3), 331–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691618805437

Furrow, J. L., King, P. E., & White, K. (2004). Religion and positive youth development: Identity, meaning, and prosocial concerns. Applied Developmental Science, 8(1), 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532480XADS0801_3

Gopnik, A., O’Grady, S., Lucas, C., Griffiths, T., Wente, A., … Dahl, R. (2017). Changes in cognitive flexibility and hypothesis search across human life history from childhood to adolescence to adulthood. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(30), 7892–7899. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1700811114

Grossmann, I., Na, J., Varnum, M. E. W., Park, D. C., Kitayama, S., & Nisbett, R. E. (2010). Reasoning about social conflicts improves into old age. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(16), 7246–7250. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1001715107

Hardy, S., Nelson, J., Moore, J., & King, P. E. (2019). Processes of religious and spiritual influence in adolescence: A review of the literature. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 29(2), 254–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12486

Immordino-Yang, M., Darling-Hammond, L., & Krone, C. (2019). Nurturing nature: How brain development is inherently social and emotional, and what this means for education. Educational Psychologist, 54, 185–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2019.1633924

King, P. E., & Boyatzis, C. J. (2015). Religious and spiritual development. In M. E. Lamb & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: Socioemotional processes (Vol. 3, pp. 1–48). Wiley.

King, P. E., & Mangan, S. (in press). Hindsight in 2020: Looking back and forward to PYD and thriving. In APA handbook of adolescent and young adult development.

King, P. E., Clardy, C. E., & Ramos, J. S. (2014). Adolescent spiritual exemplars: Exploring spirituality in the lives of diverse youth. Journal of Adolescent Research, 29(2), 186–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558413502534

King, P. E., Schnitker, S. A., & Houltberg, B. (2020). Religious groups and institutions as a context for moral development: Religion as fertile ground. In L. Jensen (Ed.), Handbook of moral development (pp. 592–612). Oxford University Press.

King, P. E., Hardy, S., & Noe, S. (2021). Developmental perspectives on adolescent religious and spiritual development. Adolescent Research Review. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-021-00159-0

Krogsrud, S. K., Fjell, A. M., Tamnes, C. K., Grydeland, H., Mork, L., … Walhovd, K. B. (2016). Changes in white matter microstructure in the developing brain: A longitudinal diffusion tensor imaging study of children from 4 to 11 years of age. NeuroImage, 124, 473–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.09.017

Lambert, N. M., Fincham, F. D., Braithwaite, S. R., Graham, S. M., & Beach, S. R. (2009). Can prayer increase gratitude? Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 1(3), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016731

Larsen, B., & Luna, B. (2018). Adolescence as a neurobiological critical period for the development of higher-order cognition. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 94, 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.09.005

Larson, R. W., Walker, K. C., & McGovern, G. (2020). Youth programs as contexts for development of ethical judgment and action. In L. A. Jensen (Ed.), Oxford handbook of moral development (pp. 552–569). Oxford University Press.

Lerner, R. M. (2018). Concepts and theories of human development (4th ed.). Routledge.

Lerner, R. M., Dowling, E. M., & Anderson, P. M. (2003). Positive youth development: Thriving as the basis of personhood and civil society. Applied Developmental Science, 7(3), 172–180. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532480XADS0703_8

McAdams, D. P. (2021). Narrative identity in the life story. In O. P. John & R. W. Robins (Eds.), Handbook of personality (4th ed., pp. 122–141). Guilford Press.

Merrill, N., & Fivush, R. (2016). Intergenerational narratives and identity across development. Developmental Review, 40, 72–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2016.03.001

Morris, A. S., Eisenberg, N., & Houltberg, B. J. (2011). Adolescent moral development. In B. Brown & M. Prinstein (Eds.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 48–55). Academic.

Nelson, J. A., de Lucca Freitas, L. B., O’Brien, M., Calkins, S. D., Leerkes, E. M., & Marcovitch, S. (2013). Preschool-aged children’s understanding of gratitude: Relations with emotion and mental state knowledge. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 31(1), 42–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-835X.2012.02077.x

Overton, W. F. (2015). Processes, relations, and relational-developmental-systems. In W. F. Overton, P. C. M. Molenaar, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: Theory and method (Vol. 1, pp. 1–54). Wiley.

Palacios, J., Salem, B., Hodge, F., Albarrán, C., Anaebere, A., & Hayes-Bautista, T. (2015). Storytelling: A qualitative tool to promote health among vulnerable populations. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 26, 346–353. https://doi-org.ccl.idm.oclc.org/10.1177/1043659614524253

Park, C. L. (2010). Making sense of the meaning literature: An integrative review of meaning-making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin, 136(2), 257–301. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018301

Passmore, H. A., & Holder, M. D. (2016). Noticing nature: Individual and social benefits of a two-week intervention. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(6), 537–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1221126

Pfeifer, J. H., & Peake, S. J. (2012). Self-development: Integrating cognitive, socioemotional, and neuroimaging perspectives. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 2(1), 55–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2011.07.012

Riveros, R., & Immordino-Yang, M. H. (2021). Toward a neuropsychology of spiritual development in adolescence. Adolescent Research Review, 6, 323–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-021-00158-1

Riveros, R., Bakchine, S., Pillon, B., Poupon, F., Miranda, M., & Slachevsky, A. (2019). Fronto-subcortical circuits for cognition and motivation. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, Article 2781. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02781

Schnitker, S. A., King, P. E., & Houltberg, B. (2019). Religion, spirituality, and thriving: Transcendent narrative, virtue, and telos. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 29(2), 276–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12443

Suleiman, A., & Dahl, R. (2017). Leveraging neuroscience to inform adolescent health. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60, 240–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.12.010

Syed, M., Pasupathi, M., & McLean, K. (2020). Master narratives, ethics, and morality. In L. Jensen (Ed.), Oxford handbook of moral development (pp. 500–515). OUP.

Telzer, E. H., van Hoorn, J., Rogers, C. R., & Do, K. T. (2018). Social influence on positive youth development: A developmental neuroscience perspective. Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 54, 215–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.acdb.2017.10.003

Van Cappellen, P., & Saroglou, V. (2012). Awe activates religious and spiritual feelings and behavioral intentions. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 4(3), 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025986

Yaden, D. B., Haidt, J., Hood, R. W., Jr., Vago, D. R., & Newberg, A. B. (2017). The varieties of self-transcendent experience. Review of General Psychology, 21(2), 143–160. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000102

Yaden, D. B., Giorgi, S., Kern, M. L., Adler, A., Ungar, L. H., Seligman, M. E., & Eichstaedt, J. C. (2021). Beyond beliefs: Multidimensional aspects of religion and spirituality in language. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000408

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Electronic Supplementary Material

Appendix 17.S1

(PDF 182 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

King, P.E., Mangan, S., Riveros, R. (2023). Religion, Spirituality, and Youth Thriving: Investigating the Roles of the Developing Mind and Meaning-Making. In: Davis, E.B., Worthington Jr., E.L., Schnitker, S.A. (eds) Handbook of Positive Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-10274-5_17

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-10274-5_17

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-10273-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-10274-5

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)