Abstract

In 2007, the Policy Document on the Impacts of Climate Change on World Heritage Properties was adopted by the World Heritage (WH) Committee, and a revised policy document, the Draft Policy Document on Climate Action for World Heritage, was released in 2021. An English word search on terms related to potential conflicts between WH and climate change was undertaken and utilised as a starting point for an exploration of developments over the 14 intervening years. Four themes were defined and explored, namely, mission, change, loss, and responsibility. In many cases of perceived conflict, professionals and policy makers have been actively working to find solutions. In others, there is the potential for developing new and creative approaches that will ensure the relevance of heritage in an uncertain future.

Since this article was accepted for publication the General Assembly of the World Heritage Committee meeting in Paris (24–26 November 2021) failed to adopt the new Policy Document on Climate Action for World Heritage. The policy could not be agreed due to lobbying, by the Australian government in particular, against commitments on Greenhouse Gas Mitigation and use of the List of World Heritage in Danger.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The Paris Agreement of 2015, an agreement within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), aims to keep global temperature rise below 2 °C through emissions reductions, i.e., the mitigation of greenhouse gasses (GHG) (UN, 1992). Accepting that some degree of climate change (CC) is now inevitable, however, the Paris Agreement has also established the Global Goal on Adaptation, whereby all signatories agree to engage in adaptation planning and the implementation of actions. Adaptation is “the process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and its effects…[it] seeks to moderate or avoid harm or exploit beneficial opportunities” (IPCC, 2014, p. 1758). The concept of “climate action” encompasses both adaptation and mitigation (UNDP, 2021) and is, therefore, a process with which parties to the Paris Agreement have committed to actively engaging. Although the list of 195 signatories to the Paris Agreement includes every State Party (SP) to the World Heritage (WH) Convention, CC adaptation and mitigation create the potential for disputed approaches for many WH properties. This paper will discuss some of the tensions between climate action and WH governance and what policy efforts have been or could be made to ensure the two coalesce rather than clash.

2 Background

Climate change (CC) was first brought to the attention of the WH Committee in 2005 when it received a petition to place four natural heritage sites on the List in Danger due to CC threats (Dannenmaier, 2010; Thorson, 2008). The Committee turned down the proposal, but its resultant decision (05/29.COM/7B.a) made several recommendations that raised the issue of CC as a major concern for both natural and cultural heritage sites for the first time (UNESCO, 2005). The WH Convention (1972) does not specifically mention CC, but SPs are obliged to protect their sites from damaging impacts. In theory, this could be interpreted as an obligation for SPs to the Convention to support the principles of climate action (Gruber, 2008), i.e., mitigating GHGs to prevent increasing CC exposure for WH and implementing adaptation measures to protect against climate impacts.

In 2007, the Policy Document on the Impacts of Climate Change on World Heritage Properties was adopted by the WH Committee. Ten years later, they requested the WH Centre and the Advisory Bodies to review and update the policy document “to make available the most current knowledge and technology on the subject to guide the decisions and actions of the World Heritage community” (UNESCO, 2016, para. 16). A subsequent meeting of experts tasked with reviewing the 2007 policy gave several recommendations, including that it should be rewritten rather than updated (IANC, 2017). In 2019, two consultants were tasked with drafting this new policy, and one of their first steps was to develop an online questionnaire for WH stakeholders. The response to the questionnaire highlighted the barriers that had inhibited the implementation of the 2007 policy (UNESCO, 2020). These included lack of resources, leadership, knowledge, and political support. The policy document was criticised for being too general and not including site-focused solutions; amendments to the Operational Policy and nomination process as well as Periodic Reporting and Reactive Monitoring processes to include the consideration of CC or make it mandatory were suggested by respondents.

The updating of the 2007 policy document on the impacts of CC on WH properties Draft Policy Document on Climate Action for World Heritage was released in 2021. Although framed as an update, the document is substantially different from the 2007 policy and departs from it in many significant ways. Interestingly, the draft policy also notes the potential for conflict and tension between CC and WH in a few areas. These include the possible adverse impacts of adaptation or mitigation actions on Outstanding Universal Value (OUV), authenticity and integrity (paras 38 and 94), and the risks of maladaptation and social disruption (para 49). In July 2021, the WH Committee meeting in China, broadcast publicly online, voted to endorse this draft and to send it to the Convention’s General Assembly for debate and adoption in the autumn (decision 21/44.COM/7C).

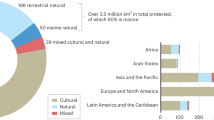

As part of the project 50 Years World Heritage Convention: Shared Responsibility – Conflict & Reconciliation, points of potential conflict between WH and climate action were discussed and refined at an expert think tank held in March 2021. To explore how policy approaches to these issues have changed from 2007 to 2021, an English word search on both documents was undertaken using related terms (Table 19.1). The word search took the key areas of conflict identified during the think tank discussion as a starting point and, following a period of literature review, these were grouped into sets according to thematic concepts or areas, e.g., “mission”. Truncations were used where relevant to ensure all variations of a keyword were found, e.g., sustainab*. There is a degree of overlap between the sets, and the list is iterative; the concept of transform*, for example, was added after its significance in the 2021 policy approach was noted. The relative occurrence of each term in the two texts is utilised in this article as a starting point to discuss developments over the fourteen years since the first policy was written (Figs. 19.1 and 19.2).

3 Mission

In 2007, when the UNESCO General Assembly adopted the Policy Document on the Impacts of Climate Change, it was accompanied by a report on Climate Change and World Heritage, the outcome of an expert advisory group meeting (Cassar et al., 2006; Colette, 2007). The report utilised expert judgement to determine how future CC might impact heritage values worldwide and emphasised the interconnection between the physical and social impacts of CC, suggesting that the way people interact with their heritage and the relevance and value of that heritage to their lives may alter with CC. The WH Committee (07/29.COM/7B.a) also requested that the WH network of sites be used to demonstrate best practice in relation to CC management and raising of public awareness (Cassar et al., 2006). This was accomplished in part by Case Studies on Climate Change and World Heritage, a UNESCO publication that used case studies to communicate the issues in an engaging way (Colette, 2009).

In 2005, when UNESCO first called on heritage organisations around the world to embrace the issue of CC, some SPs were vociferous in their opposition to the move for political reasons (Barthel-Bouchier, 2015, p. 157). For example, the Republican US government had not ratified the Kyoto Protocol and was hostile to GHG mitigation at home (Coil, 2007). Barthel-Bouchier (2015) highlights the internal conflict that heritage as an organisational field faced when first engaging with CC, a divisive issue at the time. The danger of perceived ‘mission change’ for any organisation is that it can alienate public and government support, and it is vital, therefore, that the new direction of the organisation is communicated in a way that makes “it appear a logical extension of the organisation’s charge rather than a betrayal of it” (Barthel-Bouchier, 2015, p. 151). The construction of a WH mission in relation to CC occurred over the following years and mainly focused on impacts, effectively building consensus by emphasising heritage as a victim of CC (Colette, 2007; ICOMOS, 2008; World Monuments Fund, 2007).

More challenging issues, such as the increase in GHG emissions due to heritage tourism or the need for burden sharing between developed and less developed SPs to the Convention, were largely left out of this early conversation. An exponent of this approach, Terrill (2008) argued that the WH Convention should focus on impacts only and stay out of the politically loaded arena of GHG mitigation as this was the purview of other treaties:

On grounds of expertise alone, the World Heritage Convention is well advised to avoid moving from describing problems and possible adaptation responses at World Heritage Sites to advocating particular mitigation levels or approaches. (p. 397)

More recently, however, the heritage community have been emphasising issues of climate justice and the potential for heritage to have high ambition and make a more active contribution to climate action (ICOMOS, 2019; IUCN, 2014). The United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (SDG) Goal 13 calls for all countries to “take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts” (UNDP, 2021), and ICOMOS’s policy guidance on SDG 13 is to harness heritage “to enhance the adaptive and transformative capacity of communities and build resilience against climate change” (Labadi et al., 2021, p. 89). CC is considered a cross-cutting issue and is intrinsic to the other 16 SDG Goals, and ICOMOS presents case studies that illustrate the same is true of heritage (Labadi et al., 2021). The belief that high mitigation ambitions lie outside the remit of WH still persists, however, and was raised during the debate on the CC policy decision 44.COM/7C. Amendments reflecting this view were proposed by Brazil and supported by several other SPs.

The policy word search revealed that the emphasis on “impact(s)” has reduced substantially in 2021, effectively halving in relative occurrence when compared to 2007. This indicates alignment with the wider discourse on the topic. While the 2007 plan does not mention “equity” or “justice” at all, the incidence of these concepts in 2021 is only slightly better (3 and 1, respectively). These occurrences are linked with inclusive and rights-based approaches to the governance of WH (paras 82 and 83) and with sustainable development (para 24). The draft policy points to the 2017 UNESCO Declaration of Ethical Principles in Relation to Climate Change (2021, para. 83) for a framework that can address justice and equity and the need for transparent decision making. These ethical principles include the prevention of harm, equity and justice, sustainable development, solidarity and scientific knowledge and integrity in decision making (UNESCO, 2017). The principles could provide an ethical roadmap for the future operation of the WH Convention’s climate change policies.

4 Change

CC adaptation is likely to require a new approach to change management and the conceptualisation of “acceptable levels” of change (Daly et al., 2020). In the last century, conservation practice had already moved away from the rigidity of arresting change to the flexibility of managing it (Melnick, 2009, p. 41). The Burra Charter, for example, recognises that all places and their components change over time at varying rates (Australia ICOMOS, 2000, p. 2). Given the potential effects of rapid global CC, however, the profession may need to develop a new understanding of what “managing change” means (Melnick, 2009). Harvey and Perry (2015, p. 3) argue that, in a time of rapid change, society needs a new view of heritage, one that “embraces loss, alternative forms of knowledge and uncertain futures”. They suggest that the heritage field must not only accept transience but should welcome the challenge that this will pose to the current thinking and power structures, using it to transform creatively (Harvey & Perry, 2015, p. 11).

It may indeed be the case that a fundamental shift in ethos is required, and this is likely to be a challenge for the WH system, which relies heavily on concepts of defined values, integrity, and (for cultural sites) authenticity. The idea that heritage managers should facilitate the transformation of the resources in their care to a new state more compatible with a changed climate would seem to be in direct conflict with the notion of maintaining OUV and, therefore, with WH status itself. In the worst-case scenario view, a fear of losing WH designation could inhibit SPs from admitting the scale of CC impact or even undertaking necessary adaptive responses. What Boccardi (2019) calls the “inherent vagueness” of the concept of authenticity may prove sufficiently flexible in interpretation and application to accommodate a response to the challenge of CC. The same does not hold true for the characteristic of integrity, applicable to both natural and cultural properties. Integrity is less mutable than authenticity; relating to “wholeness” and “intactness” of physical elements, it may also include quantifiable indicators such as numbers of species (Stovel, 2007). Paragraph 166 of the Operational Guidelines (UNESCO, 2019) outlines the procedure for modifying the criteria for a property inscribed on the World Heritage List. The initiative for this action must come from the SP concerned and requires a significant burden of paperwork and a minimum of a year and a half preparation.

Where a State Party wishes to have the property inscribed under additional, fewer or different criteria other than those used for the original inscription, it shall submit this request as if it were a new nomination. (UNESCO, 2019, para. 166)

Statements of value are not static and absolute; they are constructed and defined at a particular time and context (Boccardi, 2019,p. 16). Facilitating the review of statements of OUV, perhaps via the prism of integrity and authenticity, with a less burdensome procedure should be a priority as part of CC adaptation planning. In the word search results of the two policies, the relative incidence of “adaptation” increased only slightly in 2021 when compared to 2007. More significant, however, was the introduction of the term “transformation” in the 2021 plan and the associated concept of transformative change.

Under the heading of Climate Action, the 2021 policy states that four key categories are required for WH properties (assessing risks, adaptation, mitigation, and capacity building) but adds an additional fifth concept called “transformative change” (UNESCO, 2021, p. 14. This text is ambitious in the vision it sets out; it stresses the “urgency and scale of action required by the World Heritage Convention to support bold decisions to transition to a carbon neutral and resilient world that can sustain World Heritage properties for future generations” (UNESCO, 2021, para. 73). It points to unsustainable cultures of consumption and the call of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and others for societal reform or “transformative change”. The inclusion of this concept in the policy is an acknowledgement that change is not just inevitable but, if embraced as a “system-wide reorganisation…including paradigms, goals and values”, represents the key to successfully addressing the current climate and ecological crisis both for WH and society as a whole.

In the context of the World Heritage Convention, transformative change would be exemplified by decisions that contribute towards making World Heritage properties carbon neutral, as much as possible, and more resilient and better adapted to a changing climate, while safeguarding their Outstanding Universal Value…properties can embrace transformative change to become demonstration cases of the change the world needs. (UNESCO, 2021, para. 8)

5 Loss

Where CC does result in an irreversible and unmanageable loss of OUV, the WH Committee will face conflict and tensions over how to proceed. Landscape-based approaches offer an approach to exploring environmental change and loss as they are dynamic and capable of navigating time and space, nature and culture (Ferraby, 2015). In a case study of the Jurassic Coast WH site, Ferraby illustrates that loss is part of the process of creating heritage and not necessarily a negative thing.

It is important to see that these stories and narratives of people and nature can be drawn as much from what is gone as what remains; absent spaces in the environment form and emphasise histories in the living, physical traces. (Ferraby, 2015: 28)

While this may be the case for individual sites, it will be a massive challenge for the WH system to prepare itself for the potential loss of an unknown but likely rapidly escalating number of sites. Entry onto the List of WH in danger, intended to encourage and support governments to take action to protect sites, is often resisted as it is seen as a ‘black mark’ (Terrill, 2008; Readfearn, 2021).

One of the criteria in the Operational Guidelines for the inscription of a property on the List in Danger is “threatening impacts of climatic, geological or other environmental factors” which could have deleterious effects on its inherent characteristics (UNESCO, 2019, para. 179–180). The Guidelines go on to specify that such threats “must be those that are amenable to correction by human action” (UNESCO, 2019, para. 181). The list of sites in danger is therefore arguably not an appropriate vehicle to address CC, as the causes and solutions are beyond the ability of any one SP to address. The only other mechanism for dealing with sites that have lost their OUV, however, is delisting. According to the Operational Guidelines, properties could be deleted from the WH list “if the property has deteriorated to the extent that it has lost those characteristics which determined its inscription on the World Heritage List” (UNESCO, 2019, para. 191). Writing about this issue in 2008, Terrill (2008, p. 395) argued that the credibility of the WH Convention depended on establishing a clear framework for determining loss of OUV to avoid procedural complications when the inevitable difficult decisions must be made.

The UNFCCC established the concept of common but differentiated responsibilities amongst SPs (UN, 1992, Sec. 3.1). This essentially commits developed countries, those most responsible for GHG emissions, to taking the lead in combating CC and its effects. During the WH Committee debate on the policy document, the lack of mechanisms for capacity building assistance and technology transfer (from developed to developing SPs) was noted as an issue that needed to be addressed, as was the lack of reference to the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities. Many early WH losses are likely to be in low-income and small-island-developing nations (Markham et al., 2016). The process of delisting could therefore initiate a political crisis for the WH Convention, and the urgent institution of a process to ensure climate justice and burden sharing is vital for maintaining its reputation. This could be accomplished via UNESCO’s sixth ethical principle, “Solidarity”, which describes how, on a global scale, assistance should be given to those that are most vulnerable to climate change (UNESCO, 2017, Art. 6). Although there is a much greater occurrence of the word “loss” in the 2021 policy, up from 5 in 2007 to 22 uses, there is a continued lack of concrete proposals for how degradation of OUV will be handled. The draft policy largely avoids confronting the issue. There are no mentions of “delisting” and only 3 of the “List of Heritage in Danger” in the text, although both were present in 2007 (2 and 8 mentions, respectively). The proposal to place the Great Barrier Reef on the List in Danger during the 2021 WH Committee meeting brought this issue to the fore, with the Australian government successfully lobbying against the action (Readfern, 2021). When it came to the CC policy debate, Australia added an amendment, providing for the formation of an expert group to examine tensions around OUV, delisting, and CC.

The 2007 policy states that existing tools will be utilised to deal with threats to OUV, but, if necessary, the WH Committee will consider taking climate change into account in the revision of these tools (List of World Heritage in Danger, Reactive Monitoring and Periodic Reporting) and of its Operational Guidelines (UNESCO, 2007). The 2021 policy has substantially fewer mentions of the Operational Guidelines (6 vs 13 in 2007) and the other tools of the Convention. It does say that the actions in the plan ‘could’ be supported at the Committee level by ensuring that basic documents of the World Heritage system, such as the Operational Guidelines and the Resource Manuals, adequately address climate change (UNESCO, 2021, para. 86). Processes and tools were clearly flagged as a priority issue by the stakeholder questionnaire undertaken in advance of the drafting; however, unlike the 2007 policy, which contained several detailed suggestions (never implemented), the 2021 policy takes a strategic approach and requires supplementary implementation guidance.

6 Responsibility

The mitigation of GHGs by retrofitting historic buildings or installing renewable energy sources (solar panels on buildings, wind turbines in landscapes) can cause some conflicts (BBC, 2021). This tension is recognised in the 2021 WH policy in paragraph 94, which suggests proactively developing planning processes that avoid or mediate conflicts around proposed renewable projects and other emission reduction actions. More significant was the introduction of several concepts that were either largely (relative incidence <2%) or completely missing in 2007 and which reflect developments over the intervening years. These terms relate to high ambition and the contribution of WH to climate action, namely “sustainability”, “emissions”, and “transformation” (see Sect. 19.4).

Another problem in respect of emissions is the socio-economic development model that has linked WH status with the generation of international tourism revenue (Rebanks Ltd., 2009). In 2018, the carbon footprint of global tourism was calculated as 8% of worldwide emissions and was projected to grow by 4% every year (Lenzen et al., 2018). What Barthel-Bouchier (2015, p. 161) describes as the “mythic narrative of sustainable tourism” continues to be put forward as a solution, yet how the contradiction can be resolved in practice remains unclear. When it comes to climate change adaptation, the tourism imperative will unfortunately also tend to focus resources on sites that are most profitable (e.g., Venice flood defences), also raising the problem of equity and climate justice. Barthel-Bouchier (2015) challenges the heritage community to examine our collective conscience when she writes that, by aligning heritage so closely with economic returns from tourism, we

…have provided ideological and pragmatic support for a status quo that has made only minimal contributions in the face of the major challenges associated with climate change [and] over time it will become increasingly difficult to…deny evident contradictions between these two missions. (p. 162)

A very notable and welcome development in the 2021 policy, therefore, is the inclusion of references to “tourism”. Not referred to at all in 2007, it received 22 mentions in 2021. This inclusion reflects the growing awareness of the contribution heritage tourism makes to economic development but also of the problematic implications this has for GHG emissions reduction (Markham et al., 2016). The emphasis in the main policy text is on the problems of “uncontrolled tourism”, the issue of emissions is recognised, but no critical analysis is provided, and the unchallenging solutions are “tourism management” and “sustainable tourism”. Experiences during the Covid-19 pandemic point to the importance of heritage for wellbeing, and while international tourism with its high carbon footprint is problematic, the widening of access to a diversity of local visitors should be encouraged. Annex III in the 2021 policy frames key areas for WH properties to reduce emissions such as tourism, and more concrete suggestions are also proposed, including monitoring of GHG emissions from tourism, identifying carbon saving measures, and considering offsetting.

7 Conclusion

This paper sought to explore potential conflicts and synergies between the WH system and climate action via a discussion of the 2007 and 2021 policies. As all SPs to the WH Convention are also signatories of the Paris Agreement, it is vital that potential conflicts between commitments under these instruments are recognised and addressed. Heritage professionals and policy makers have been actively working to develop new and creative approaches for dealing with potential conflicts and identifying confluences, ensuring the relevance of heritage in an uncertain future. The new WH policy reframes the debate and clearly represents an attitude shift from the 2007 document, as was seen from the results of a simple word search. The concepts of transformative change, high ambition, and adoption of the UN Ethical Principles all have implications for practice and create clear synergies between WH and other instruments, including the UNFCCC. Changes to the Operational Guidelines, WH tools, and processes are still required, and CC needs to be assessed at all stages of listing and in subsequent reporting. Consideration needs to be given to a range of ideas such as the creation of a specific CC List in Danger, more streamlined methods for SPs to request adjustment of OUV criteria for sites already on the list, mechanisms for dealing with CC in the nomination process, and a means to show solidarity for inevitable losses. Attention is needed to ensure climate justice and burden sharing between nations is part of the process, starting with capacity building and technology transfer between high- and low-income SPs. In the first decade of this century, WH led the heritage sector in highlighting climate change impacts. In this third decade, it could lead in Climate Action, reaffirming the leadership role of WH and ensuring its relevance for generations to come.

References

Australia ICOMOS. (2000). The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for places of cultural significance 1999, with associated guidelines and code on the ethics of co-existence in conserving significant places. Australia ICOMOS. http://australia.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/BURRA_CHARTER.pdf

Barthel-Bouchier, D. (2015). Heritage and climate change; organizational conflicts and conundrums. In D. C. Harvey & J. Perry (Eds.), The future of heritage as climates change loss, adaptation and creativity (pp. 151–166). Routledge.

BBC. (2021). Proposed power line would cross Antonine Wall. British Broadcasting Company. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-tayside-central-57061971

Boccardi, G. (2019). Authenticity in the heritage context: A reflection beyond the Nara document. The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice, 10(1), 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/17567505.2018.1531647

Cassar, M., Young, C., Weighell, T., Sheppard, D., Bomhard, B., & Rosabel, P. (2006). Predicting and managing the effects of climate change on World Heritage: A joint report from the World Heritage Centre, its advisory bodies, and a broad group of experts to the 30th session of the World Heritage Committee (Vilnius 2006). UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

Coil, Z. (2007). How the white house worked to scuttle California’s climate law. San Francisco Chronicle. https://web.archive.org/web/20130617052823/http://www.commondreams.org/archive/2007/09/25/4099.

Colette, A. (2007). Climate change and World Heritage: Report on predicting and managing the impacts of climate change on World Heritage and strategy to assist States Parties to implement appropriate management responses. UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

Colette, A. (2009). Case studies on climate change and World Heritage. UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

Daly, C., Engel-Purcell, C. Chan, C., Donnelly, J., MacDonagh, M. & Cox, P. (2020). Climate change adaptation planning, a national scale methodology. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development. Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHMSD-04-2020-0053

Dannenmaier, E. (2010, September 19). International tribunals as climate institutions? Strengthening access to climate justice [conference paper]. Yale/UNITAR Second Conference on Environmental Governance and Democracy. .

Ferraby, R. (2015). Narratives of hange on the Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site. In D. C. Harvey & J. Perry (Eds.), The future of heritage as climates change loss, adaptation and creativity (pp. 25–42). Routledge.

Gruber, S. (2008). Environmental law and the threat of global climate change to cultural heritage sites Sydney Law School Research Paper No. 08/117 [conference paper]. Climate law in developing countries post-2012: North and South perspectives, IUCN, academy of environmental law, Faculty of Law, University of Ottawa, Canada, pp. 26–28.

Harvey, D. C., & Perry, J. (2015). Heritage and climate change, the future is not the past. In D. C. Harvey & J. Perry (Eds.), The future of heritage as climates change loss, adaptation and creativity (pp. 3–21). Routledge.

ICOMOS. (2008). Heritage at risk: ICOMOS World Report 2006–2007 on monuments and sites in danger. hendrik Bäßler verlag.

ICOMOS Climate Change and Cultural Heritage Working Group. (2019). The future of our pasts: Engaging cultural heritage in climate action. ICOMOS. https://indd.adobe.com/view/a9a551e3-3b23-4127-99fd-a7a80d91a29e

International Academy for Nature Conservation. (2017). World Heritage and climate change – Towards the update of the policy document on the impacts of climate change on World Heritage properties. [unpublished report] International Expert Workshop.

IPCC. (2014). Annex II: Glossary [Mach, K.J., S. Planton and C. von Stechow (eds.)]. In R. K. Pachauri & L. A. Meyer (Eds.), Climate change 2014: Synthesis report. Contribution of working groups I, II and III to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (pp. 117–130). IPCC.

IUCN. (2014). The benefits of natural World Heritage: Identifying and assessing ecosystem services and benefits provided by the world’s most iconic natural places. IUCN. https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/44901

Labadi, S., Giliberto, F., Rosetti, I., Shetabi, L., & Yildirim, E. (2021). Heritage and the sustainable development goals: Policy guidance for heritage and development actors. ICOMOS.

Lenzen, M., Sun, Y. Y., Faturay, F., Ting, Y. P., Geschke, A., & Malik, A. (2018). The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nature Clim Change, 8, 522–528. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0141-x

Markham, A., Osipova, E., Lafrenz Samuels, K., & Caldas, A. (2016). World Heritage and tourism in a changing climate. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi, Kenya and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. UNESCO.

Melnick, R. Z. (2009). Climate change and landscape preservation: A twenty-first-century conundrum. APT Bulletin, 40, 35–42.

Readfern, G. (2021). World Heritage Committee agrees not to place great barrier reef on ‘in danger’ list. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/jul/25/the-great-barrier-reef-is-not-on-the-in-danger-list-why-and-what-happens-next

Rebanks Consulting Ltd. (2009). World Heritage status, Is there opportunity for economic gain? Research and analysis of the socio-economic impact potential of UNESCO World Heritage site status. Lake District World Heritage Project. WHS-Lake-District-Economic-Gain-Doct..pdf (engageliverpool.com)

Stovel, H. (2007). Effective use of authenticity and integrity as World Heritage qualifying conditions. City & Time, 2(3), 3. http://www.ct.ceci-br.org

Terrill, G. (2008). Climate change: How should the World Heritage Convention respond? International Journal of Heritage Studies, 14(5), 388–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250802284388

Thorson, E. J. (2008). On thin ice: The failure of the United States and the World Heritage Committee to take climate change mitigation pursuant to the World Heritage Convention seriously. Environmental Law, 38, 139–176.

UNDP. (2021). Sustainable development goals. Climate Action. United Nations. https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals#climate-action

UNESCO. (2005). Decisions of the 29th session of the World Heritage Committee. (05/29.COM/7B.a). UNESCO.

UNESCO. (2007). Policy document on the impact of climate change on World Heritage properties (WHC-07/16.GA/10). Sixteenth session of the general assembly of states parties to the convention concerning the protection of the world cultural and natural heritage. UNESCO.

UNESCO. (2016). Decision 40.COM 7 state of conservation of World Heritage properties. 40th session of the World Heritage Committee. UNESCO.

UNESCO. (2017). Declaration of ethical principles in relation to climate change Records of the General Conference, 39th session, Paris, 30 October–14 November 2017, v. 1: Resolutions. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000260889.page=127

UNESCO. (2019). Operational guidelines for the implementation of the World Heritage Convention. Intergovernmental Committee for the Protection of the world cultural and natural heritage. World Heritage Centre, UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines

UNESCO. (2020). Updating of the policy document on the impacts of climate change on World Heritage properties. Summary of the online consultation (30 December 2019–31 January 2020). [Unpublished].

UNESCO. (2021). Draft policy document on climate action for World Heritage. World Heritage Centre, UNESCO.

United Nations. (1992). United Nations framework convention on climate change, (A/CONF/151/26). United Nations. https://unfccc.int/files/essential_background/background_publications_htmlpdf/application/pdf/conveng.pdf

World Monuments Fund. (2007). World monuments watch 2008 list of 100 Most endangered sites. https://www.wmf.org/sites/default/files/press_releases/pdfs/2008%20Watch%20List.pdf

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Daly, C. (2022). Climate Action and World Heritage: Conflict or Confluence?. In: Albert, MT., Bernecker, R., Cave, C., Prodan, A.C., Ripp, M. (eds) 50 Years World Heritage Convention: Shared Responsibility – Conflict & Reconciliation. Heritage Studies. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-05660-4_19

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-05660-4_19

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-05659-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-05660-4

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)