Abstract

Climate change is the greatest threat facing global natural and cultural heritage. All World Heritage (WH) properties will be impacted over the coming century, and our ability to adapt will often be limited. Yet climate change was a threat never envisioned by the drafters of the World Heritage Convention (WHC). This chapter considers how concepts central to the WHC may need to adapt to a rapidly changing world, to reflect three uncomfortable realities of the climate crisis and its impacts on heritage sites. Firstly, climate change is and will continue threatening and invalidating the Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) of many properties, and there may be little we can do to stop this. Secondly, climate change knows no borders and existing mechanisms may need to be rethought to reflect this. Thirdly, these challenges will, like climate change, disproportionately impact marginalised and indigenous communities in the Global South. It is suggested here that more precise and explicit guidance, which considers local climate modelling and an inclusive approach to values, within the existing proactive mechanisms of the WHC Operational Guidelines would result in a more consistent consideration of climate change impacts at WH properties, that reflects the spirit of the WHC.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

It has been 50 years since world leaders established the World Heritage Convention (WHC). This visionary document sought to protect places of Outstanding Universal Value, acknowledging for the first time the universal value of some places. At this key point of reflection, our global heritage faces a new threat which was not foreseen by the authors of the 1972 Convention. The impacts of anthropogenic climate change are global and transcend the more localised threats to heritage identified in the original document. Either directly or indirectly, all World Heritage properties are or will be impacted by climate change. As a heritage community, it is imperative that we use this significant anniversary to critically evaluate our ability to respond to this challenge. This reflection should start with our founding documents, including the WHC and its subsequent Operational Guidelines (most recent edition 2019). The utility of these documents to World Heritage management within the climate crisis is explored in this chapter, which opens with an overview of the current state-of-the-art in research and policy before focusing on the need to adopt a more values-based approach to understanding impacts, vulnerabilities and adaptation planning that is more sympathetic to inevitable change.

2 Climate Change and Heritage

Recent years have seen an increasing focus within the heritage community on the impacts of climate change on heritage. The IUCN World Heritage Outlook 3, published in 2020, noted that one-third of properties are in danger (Osipova et al. 2020). In the same year, the 20th ICOMOS General Assembly overwhelmingly voted to declare a climate and ecological emergency, building on escalating actions, including the publication of their 2019 Future of our Pasts (FooP) report (ICOMOS, 2019). Within the cultural heritage sector, the quantity of papers in high-ranking journals and special editions focused on the subject are increasing, reflecting a growing understanding of the urgency of the climate crisis (Fatorić & Seekamp, 2017; Sesana et al., 2021). There has also been increased public interest, with media attention focused on damage and loss at iconic sites such as Venice and Rapa Nui, and increasing interest and concern about the loss of local heritage (Megarry & Hadick, 2021). These examples emphasise the impacts of climate change on cultural heritage and the immense communicative power of these special places to stress urgency and promote action (Rockman & Maase, 2017).

Impacts on cultural heritage are both direct and indirect. Fatoric and Seekamp (2017) provide an excellent overview of the themes and modalities of these studies, which have varied from focusing on certain subsets of heritage or regions (Brooks et al., 2020; Hollesen et al., 2018; Perez-Alvaro, 2016; Reimann et al., 2018); to taking a broader impact-focused approach as outlined in both the ICOMOS FooP report (2019) and Sesana et al. (2021). Indirect impacts have been less well researched, perhaps due to their inherently complex, multifaceted and commonly regional or site-specific manifestations, where climate change often acts as a risk multiplier for existing stressors. The ICOMOS FooP dedicates substantial discussion to some of the “cross-cuttin” issues, which include equity and climate justice and the relationship between climate action and sustainable development (ICOMOS, 2019. The inclusion of heritage issues into climate policy has been less common, with some notable exceptions (Daly, 2019; Fluck, 2016).

3 The World Heritage Convention and Climate Change

Identifying and preparing for climate change impacts are already embedded, both explicitly and implicitly, within the WHC and its Operational Guidelines. The text of the WHC identifies a range of threats and specific impacts to heritage in Article 11.4, which introduces the concept of the “List of World Heritage in Danger”. This is a reactive mechanism for supporting and providing assistance to properties and State Parties and reflects “serious and specific dangers”. It includes an indicative list of examples, which (unsurprisingly) omits climate change (WHC 11.4). Climate change was first mentioned in the 1997 revision of the Operational Guidelines for the implementation of the WHC, which included it as a potential environmental pressure in the “Format and content of nominations” section (Article 64). It remained in this section until 2005 when this guidance was placed in a separate annex (Annex 5). It only returned to the main text in the 2017 version where it is explicitly mentioned in Articles 111 and 118, which discuss the importance of environmental, heritage and strategic impact assessments to “ensure the long-term safeguarding of the Outstanding Universal Value, and the strengthening of heritage resilience to disasters and climate change” (UNESCO, 2019). It appears again in Article 239, which addresses international assistance, and, while not explicitly named in the guidelines, climate change is often included in periodic reporting and state of conservation reports and in secondary guidance documents. These mechanisms allow for both the proactive (within the nomination process, state of conservation (SOC) reports and in periodic reporting) and reactive (reactive missions, List of WH in Danger) inclusion of climate impacts at sites. An increasing number of WH properties are including climate impacts within these mechanisms, for example, in the SOC reporting. Often, threats like wildfire or extreme weather may be identified without specifically considering the underlying cause, climate change. However, the lack of explicit and specific guidance on climate vulnerability assessment means that the extent of its inclusion (or omission) can vary from site to site and can reflect local or national factors, including capacity, politics or even just the priorities of an individual assessor.

The primary policy document for WH sites and climate change remains the 2007 UNESCO Policy Document on the Impacts of Climate Change on World Heritage Properties (UNESCO, 2008). In many ways, this document was ahead of its time, stressing global urgency and acknowledging wide-ranging direct and indirect impacts on properties. Its utility was (by design) limited to some key issues, including identifying synergies between WH policy with other key climate drivers, proposing key research needs and addressing legal questions and alternative mechanisms for heritage decision and policy makers. Current efforts by advisory committees to update this document are at an advanced stage.

The WHC and its Operational Guidelines are visionary and seminal documents for global heritage management and its mechanisms have evolved to include considerations of climate change. While these can be effective for many sites, the assessment of climate impacts at many properties remains largely reactive. This poses a challenge for conservation where proactive adaptation is required. One major problem here is that the inclusion of climate impacts alongside other threats creates a false equivalence, which undermines the scale of the climate crisis and its impact on heritage sites. In many cases, local action or adaptation will not be enough to address impacts that must be addressed at a global scale and in line with existing policies and drivers. There is a need for clear and explicit guidance for all WH properties and not just those deemed at immediate threat from climate change. Climate change is not an acute threat affecting selective WH properties. It is now the single largest threat to all cultural and natural heritage sites across the planet. To illustrate this point, the next section will address some specific challenges to the implementation of the WHC in a climate emergency.

4 Climate Change and the Challenge of Outstanding Universal Value

By design, the WHC and its Operational Guidelines are primarily focused on establishing and preserving the Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) of WH properties, and this OUV is substantiated through attributes which align with the ten criteria outlined in the Operational Guidelines. These attributes are entwined with complementary concepts of integrity and authenticity, which must be met and maintained to protect the WH status of properties and are outlined in a statement of OUV (SOUV). While wider sites or property values may change over time, the SOUV is set in stone and cannot be easily changed. The Operational Guidelines for the WHC stress the importance of including and acknowledging a range of values in the SOUV at the point of inscription and that these need to be protected. Understanding the significance, attributes and associated values of heritage properties is central to their preservation and conservation, yet concepts of significance and values are multifaceted and can have a range of meanings as outlined in The Burra Charter (Australia ICOMOS, 2013). This plurality of significance and values echoes the influential Nara Convention, which emphasises the cultural specificity of values (ICOMOS, 1994). This inclusive approach is central to more recent drafts of the WHC Operational Guidelines and has largely been embraced by more recent WH sites, which make explicit connections between heritage values and local communities in the SOUV, reflecting wider drivers for sustainable development.

This SOUV is not just the key to inscription but also an essential part of the ongoing monitoring of sites, as threats to the OUV of a property constitute a threat to its WH status. Given the desire to protect OUV, integrity and authenticity, and, in turn, the site inscription, the values contained within the SOUV are closely protected. A SOUV has both strengths and weaknesses when faced with climate change. On the one hand, they can be seen as immovable and inflexible. On the other hand, an inclusive SOUV can allow for broader interpretations that acknowledge a wider range of values and aligns them with the criteria of the WHC, which will prove more resilient to inevitable change. A more restrictive SOUV, which builds a case for OUV based solely on material or historical authenticity and integrity and does not consider wider social values, will be less flexible and less able to adapt to the impacts of climate change.

So why is climate change such a threat to the OUV of WH properties, and why do we need to consider these conflicts now? The remainder of this section will explore three key (and sometimes crosscutting) themes central to this dynamic.

4.1 Climate Change Is and Will Continue Impacting the Inscription Criteria and the SOUV of WH Properties

Climate change both directly and indirectly impacts both the physical fabric, authenticity and integrity of WH properties and other aesthetic, historic, scientific, social and spiritual values. This is inevitable, and many properties can be saved, but a minority cannot. In the climate emergency, we must prepare to manage both changes to the authenticity and integrity of properties and the loss of others (Perry, 2019). Climate change is a global issue which necessitates a global response, and while local adaptation efforts may reduce the severity of some impacts, the majority of properties and landscapes are going to change. The Great Barrier Reef and other World Heritage coral reefs are examples of this dynamic (Fig. 18.1) (Heron et al., 2017). In these cases, threats to the SOUV will mean that, through no fault of their own and with no capacity or ability to adapt, properties may be interpreted by the WH centre as being at risk and added to the List of WH Sites in Danger or even removed from the WH list. The OUV of other properties are intricately connected to their geography and climates, which will likely change over the coming century. Cultural landscapes will likely bear the brunt of these changes, especially those which rely on production, such as the Coffee Cultural Landscape of Colombia or the Champagne Hillsides, Houses and Cellars in France (Silva, 2017). In these situations, there is a need to manage changes to the OUV of properties and accept the unavoidable impacts on their authenticity and integrity.

4.2 Climate Change Does Not and Will Not Respect Property Boundaries

Boundaries are an integral part of establishing and protecting OUV. Understanding the geographical context of a property is crucial to understanding its cultural significance. Article 88 of the Operational Guidelines stresses that, in order to accurately show a property’s integrity, the extent of a WHS must be of sufficient size to ‘ensure the complete representation of the features and processes that convey the property’s significance’ (UNESCO, 2019, 27). Buffer zones can also be used to add an extra level of protection. While nomination dossiers will often consider these boundaries within wider regional or national contexts, considering regional or national threats such as earthquakes, wildfires or storms relevant to site management, future climate impacts are rarely explicitly presented. In reality, the impacts of climate change are rarely restricted to the inscribed boundaries of WH properties. Direct impacts such as change of sea level, storminess or regional climate will alter large areas and result in changes at properties which cannot be adapted to. In extreme cases, particularly at coastal sites or properties on small islands, the structure of the landscape will change as sea levels rise, physically altering inscribed boundaries. An example of this is Levuka in Fiji, where the location of the signing of the 1874 Deed of Cession is eroding due to rising sea levels. In other cases, indirect impacts outside property boundaries like floods or wildfires will affect management and conservation practices as well as site sustainability. Recent fires in Australia brought this into sharp relief where threats to the Gondwana Rainforests of Australia WH property resulted in an official response from UNESCO noting the potential impact on site OUV. We must now consider a future where threats may come from outside of WH properties and where established boundaries need to be reassessed to reflect the impacts of climate change. Central to this new reality is working with climate scientists and obtaining downscaled climate models for properties and their wider landscapes.

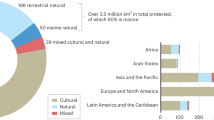

4.3 This Threat to OUV Will, Like Climate Change, Disproportionately Affect the Global South

The issue of in-country heritage professionals and State Parties being unable to prevent changes to or loss of OUV due to climate change will be particularly acute in the Global South. This climate inequality has been acknowledged by UNESCO in their 2017 Declaration of Ethical Principles in relation to Climate Change (2017), which stressed the need for global solidarity and action. More recently, the 2019 Future of our Pasts report emphasised the inequality inherent in the climate crisis from a cultural heritage perspective (ICOMOS, 2019), noting that while climate change is predominantly caused by the cumulative greenhouse gas emissions of industrialised countries, its impacts are disproportionately felt by the poorest and most vulnerable. This dynamic extends to WH properties and their capacities to adapt to climate impacts and will exacerbate an already alarming pattern of WH sites in Danger in less wealthy countries, primarily in Africa and the Arab regions where 71% of WH properties on the WH in Danger list are situated. Table 18.1 outlines the ten most affected countries between 2000 and 2019 as outlined in a 2021 report by Germanwatch, written in preparation for COP 25 in Madrid (Eckstein et al. 2021), alongside their OECD status, with the number of WH properties in each country. All but four are lower- and middle-income economies, and six are least developed countries. It is imperative that any new tools or techniques be accessible and available to the countries most at risk.

5 The Need for a Proactive Values-Based Vulnerability Assessment Tool

So, what is the solution to this dilemma? There is no one answer, but the FooP report stresses that ‘… conservation management and assessment standards, such as the constructs of authenticity and integrity, will need to be rethought’ (ICOMOS, 2019, 16). Khalaf (2020) has recently stressed that the Operational Guidelines must embrace a modality of compatibility if it is to effectively adapt to the challenges posed by climate change. I would suggest here that we must utilise existing mechanisms within the WHC Operational Guidelines to promote explicit, proactive and standardised climate impact assessment at all WH properties. These approaches must be driven by climate science and must include a wide range of values, including the SOUV of properties. They must also be scalable and applicable globally to all property typologies.

Climate impact assessment methodologies already exist for heritage sites. Examples include Perry’s (2011, 2019) World Heritage Vulnerability Index (WHVI), which incorporated nine variables but only focused on Natural World Heritage sites, and Guzman et al.’s (2020) landscape-based approaches, which can work in tandem with the conservation and management of OUV through the periodic reporting mechanism. This landscape approach would certainly go some way towards addressing the issues caused by site boundaries. A more recent approach is the climate vulnerability index (CVI), which builds on the existing IPCC assessment framework to identify risks to both the OUV and the socio-economic values of WH properties (Day et al. 2020). Central to the CVI approach is building relationships between heritage professionals and climate scientists to produce downscaled climate models for individual properties, which incorporate both direct and indirect impacts at multiple scales. It then explores the severity of these impacts against key values derived from both the SOUV and workshops involving local stakeholders. Vulnerability is then assessed for individual values (not just OUV) through an assessment of exposure and sensitivity based on adaptive capacity and resilience. The overall vulnerability of a property can be assessed by exploring the cumulative vulnerabilities of individual values. The CVI has been applied at both natural and cultural sites, including Shark Bay in Australia (Heron et al., 2020) and The Heart of Neolithic Orkney (Day et al. 2019), and is currently being undertaken at two African sites as part of the Values-based Climate Change Risk Assessment: Piloting the Climate Vulnerability Index for Cultural Heritage in Africa (CVI Africa Project). The two sites are the Sukur Cultural Landscape in Nigeria and The Ruins of Kilwa Kisiwani and Ruins of Songo Mnara in the United Republic of Tanzania. This project aims to assess the utility of the CVI technique for sites in the Global South, focusing on distinct and different property typologies and climate threats.

6 Case Study: The CVI Africa Project and the Ruins of Kilwa Kisiwani and Ruins of Songo Mnara, United Republic of Tanzania

Climate change has and is already threatening the OUV of WH properties. In some cases, it has been possible to address these impacts within the existing mechanisms of the WHC. One good example is The Ruins of Kilwa Kisiwani and Ruins of Songo Mnara WH site in the United Republic of Tanzania. It was inscribed on the WH list in 1981. The OUV for the site is based on Criterion (iii) and emphasises its architectural, archaeological and documentary values (Chami, 2019; Pollard, 2008). As with so many sites, the statements of integrity and authenticity both emphasise the material completeness of the site as being central to its OUV, while also acknowledging the potential threats to the site from a range of factors, including coastal inundation.

The Ruins of Kilwa Kisiwani and Ruins of Songo Mnara are good examples of how both direct and indirect climate impacts can threaten the OUV of WH properties. In 2004, it was placed on the List of World Heritage in Danger due to inundation by the sea and anthropogenic factors, including encroachment of building and agricultural activities. The site was removed from the list in 2014 following investment and support from the international community, including the construction of barriers to protect structures and the replanting of mangroves (Fig. 18.2); however, there remain ongoing concerns about the lack of engagement with local stakeholders (Chinyele & Lwoga, 2018; Ichumbaki & Mapunda, 2017). Lwoga (2018, 1028) noted that the associated land-use activities impacting the site were largely due to the “limited socio-economic benefits, inconsistent business opportunities, complaints about employment and payment and few feasible alternatives for making a living” for the local community who live in and around the ruins and that the conservation efforts and planning at the site do not properly engage with community needs, and further suggesting that intervention was “relatively limited to the level of tokenism” (Chinyele & Lwoga, 2018, 188; Ichumbaki & Mapunda, 2017). This is worrying as future threats to the property are likely to be considerable. Tanzania is amongst the most vulnerable countries to future impacts of climate change (IPCC, 2015). While existing adaptation efforts protect parts of the site, others remain extremely vulnerable. This disconnect between heritage and community values shows the importance of adopting a values-based approach, which includes local social-economic values alongside threats to the OUV. It is especially important in cases where the SOUV makes limited reference to these wider values beyond their inclusion in a section on the aforementioned conservation issues.

All these factors make the property a good case study for a CVI assessment. Climate impacts at the site have already been substantial, and adaptation efforts have had some success in addressing these; however, the future preservation of the property and its OUV requires greater input from local stakeholders. As part of the CVI Africa Project, an international team including partners from the Tanzania Wildlife Management Authority and ICOMOS is running a CVI workshop. It is working with Tanzanian climate scientists to produce downscaled climate models for the property and with local stakeholders and heritage professionals to identify key values which may be impacted in the future. It is hoped that this assessment will facilitate greater and more inclusive adaptation planning and protect the OUV of the property over the next century.

7 Conclusion

This chapter has explored the potential impacts of climate change on WH properties, focusing on key development opportunities within the WHC and its Operational Guidelines. It is proposed here that by adopting a values-based approach to climate impacts and responses within the existing mechanisms of the WHC, which is sympathetic to wider value systems and extends beyond the often narrow geographical extents of properties, it is possible to continue the mission of the World Heritage Convention to ‘demonstrate the importance, for all the peoples of the world, of safeguarding this unique and irreplaceable property, to whatever people it may belong’ (UNESCO, 1972, 1).

References

Australia ICOMOS. (2013). The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for places of cultural significance 2013. Australia ICOMOS.

Brooks, N., Clarke, J., Ngaruiya, G. W., & Wangui, E. E. (2020). African heritage in a changing climate. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa, 55(3), 297–328.

Chami, F. A. (2019). The archaeology of pre-Islamic Kilwa Kisiwani (Island). Studies in the African Past, 5, 119–150. Retrieved June 11, 2021, from http://196.44.162.39/index.php/sap/article/view/2686.

Chinyele, B. J., & Lwoga, N. B. (2018). Participation in decision making regarding the conservation of heritage resources and conservation attitudes in Kilwa Kisiwani, Tanzania. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development, 39, 88.

Daly, C. (2019). Built & archaeological heritage climate change sectoral adaptation plan. Department of Culture Heritage and Gaeltacht. Retrieved July 21, 2020, from http://eprints.lincoln.ac.uk/id/eprint/38705/.

Day, J. C., Heron, S. F., Markham, A., Downes, J., Gibson, J., Hyslop, E., Jones, R., & Lyall, A. (2019). Climate risk assessment for the heart of Neolithic Orkney World Heritage Site. Historic Environment Scotland.

Day, J. C., Heron, S. F., & Markham, A. (2020). Assessing the climate vulnerability of the world’s natural and cultural heritage. Parks Stewardship Forum, 36(1). https://escholarship.org/uc/item/92v9v778.

Eckstein, D., Künzel, V., & Schäfer, L. (2021). Global Climate Risk Index 2021: Who suffers most extreme weather events? Weather-related loss events in 2019 and 2000–2019. Germanwatch Nord-Süd Initiative e.V.

Fatorić, S., & Seekamp, E. (2017). Are cultural heritage and resources threatened by climate change? A systematic literature review. Climatic Change, 142(1-2), 227–254.

Fluck, H. (2016). Climate change adaptation report. (Research Report Series 28/2016). Historic England.

Guzman, P., Fatorić, S., & Ishizawa, M. (2020). Monitoring climate change in World Heritage properties: Evaluating landscape-based approach in the state of conservation system. Climate, 8(39). https://doi.org/10.3390/cli8030039

Heron, S. F., Eakin, C. M., & Douvere, F. (2017). Impacts of climate change on World Heritage Coral Reefs: a first global scientific assessment. UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

Heron, S. F., Day, J. C., Cowell, C., Scott, P. R., Walker, D., & Shaw, J. (2020). Application of the Climate Vulnerability Index for Shark Bay, Western Australia. Western Australian Marine Science Institution.

Hollesen, J., Callanan, M., Dawson, T., Fenger-Nielsen, R., Max Friesen, T., Jensen, A. M., Markham, A., Martens, V., Pitulko, V., & Rockman, M. (2018). Climate change and the deteriorating archaeological and environmental archives of the Arctic. Antiquity, 92.

Ichumbaki, E. B., & Mapunda, B. B. (2017). Challenges to the retention of the integrity of World Heritage sites in Africa: The case of Kilwa Kisiwani and Songo Mnara, Tanzania. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa, 52(4), 518–539.

ICOMOS. (1994). The Nara document on authenticity. ICOMOS.

ICOMOS. (2019). The future of our pasts: engaging cultural heritage in climate action. ICOMOS.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2015). Climate Change 2014 – Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects: Volume 1, Global and Sectoral Aspects: Working Group II Contribution to the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report. IPCC. Cambridge University Press.

Khalaf, R. W. (2020). A proposal to operationalise the concept of compatibility in World Heritage Climate Change Policy (pp. 1–23). The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice.

Lwoga, N. B. (2018). Dilemma of local socio-economic perspectives in management of historic ruins in Kilwa Kisiwani World Heritage site, Tanzania. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 24(10), 1019–1037.

Megarry, W., & Hadick, K. (2021). Lessons from the edge: Assessing the impact and efficacy of digital technologies to stress urgency about climate change and cultural heritage globally. The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice. https://doi.org/10.1080/17567505.2021.1944571

Osipova, E., Emslie-Smith, M., Osti, M., Murai, M., Åberg, U., & Shadie, P. (2020). IUCN World Heritage Outlook 3. Retrieved January 7, 2021 from https://doi.org/10.2305/iucn.ch.2020.16.en

Perez-Alvaro, E. (2016). Climate change and underwater cultural heritage: Impacts and challenges. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 21, 842–848.

Perry, J. (2011). World Heritage hot spots: A global model identifies the 16 natural heritage properties on the World Heritage List most at risk from climate change. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 17(5), 426–441.

Perry, J. (2019). Climate change adaptation in natural World Heritage sites: A triage approach. Climate, 7(9), 105.

Pollard, E. J. (2008). The maritime landscape of Kilwa Kisiwani and its region, Tanzania, 11th to 15th century AD. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 27(3), 265–280.

Reimann, L., Vafeidis, A. T., Brown, S., Hinkel, J., & Tol, R. S. J. (2018). Mediterranean UNESCO World Heritage at risk from coastal flooding and erosion due to sea-level rise. Nature Communications, 9(1), 4161.

Rockman, M., & Maase, J. (2017). Every place has a climate story: Finding and sharing climate change stories with cultural heritage. In T. Dawson, C. Nimura, E. Lopez-Romero, & M. Yvane Daire (Eds.), Public archaeology and climate change (pp. 107–114). Oxbow Books.

Sesana, E., Gagnon, A. S., Ciantelli, C., Cassar, J., & Hughes, J. J. (2021). Climate change impacts on cultural heritage: A literature review. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change. Retrieved 1/7/21 from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/wcc.710.

Silva, C. A. V. (2017). Indigenous landscapes Coffee Cultural Landscape of Colombia. Journal of World Heritage Studies Special Issue: Proceedings of the First Capacity. Building Workshop on Nature-Culture Linkages in Heritage Conservation in Asia and the Pacific, 44–50.

UNESCO. (1972). Convention concerning the protection of the world cultural and natural heritage. UNESCO.

UNESCO. (2008). Policy document on the impacts of climate change on World Heritage properties. UNESCO.

UNESCO. (2017). Annex III – declaration of ethical principles in relation to climate change. In Records of the General Conference, 39th session, Paris, 30 October–14 November 2017 (Vol. 1). Resolutions. UNESCO.

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. (2019). Operational guidelines for the implementation of the World Heritage Convention. UNESCO.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Megarry, W.P. (2022). The Climate Crisis, Outstanding Universal Value and Change in World Heritage. In: Albert, MT., Bernecker, R., Cave, C., Prodan, A.C., Ripp, M. (eds) 50 Years World Heritage Convention: Shared Responsibility – Conflict & Reconciliation. Heritage Studies. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-05660-4_18

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-05660-4_18

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-05659-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-05660-4

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)