Abstract

Case Study Research has a long tradition and it has been used in different areas of social sciences to approach research questions that command context sensitiveness and attention to complexity while tapping on multiple sources. Comparative Case Studies have been suggested as providing effective tools to understanding policy and practice along three different axes of social scientific research, namely horizontal (spaces), vertical (scales), and transversal (time). The chapter, first, sketches the methodological basis of case-based research in comparative studies as a point of departure, also highlighting the requirements for comparative research. Second, the chapter focuses on presenting and discussing recent developments in scholarship to provide insights on how comparative researchers, especially those investigating educational policy and practice in the context of globalization and internationalization, have suggested some critical rethinking of case study research to account more effectively for recent conceptual shifts in the social sciences related to culture, context, space and comparison. In a third section, it presents the approach to comparative case studies adopted in the European research project YOUNG_ADULLLT that has set out to research lifelong learning policies in their embeddedness in regional economies, labour markets and individual life projects of young adults. The chapter is rounded out with some summarizing and concluding remarks.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Exploring landscapes of lifelong learning in Europe is a daunting task as it involves a great deal of differences across places and spaces; it entails attending to different levels and dimensions of the phenomena at hand, but not least it commands substantial sensibility to cultural and contextual idiosyncrasies. As such, case-based methodologies come to mind as tested methodological approaches to capturing and examining singular configurations such as the local settings in focus in this volume, in which lifelong learning policies for young people are explored in their multidimensional reality. The ensuing question, then, is how to ensure comparability across cases when departing from the assumption that cases are unique. Recent debates in Comparative and International Education (CIE) research are drawn from that offer important insights into the issues involved and provide a heuristic approach to comparative cases studies. Since the cases focused on in the chapters of this book all stem from a common European research project, the comparative case study methodology allows us to at once dive into the specifics and uniqueness of each case while at the same time pay attention to common treads at the national and international (European) levels.

The chapter, first, sketches the methodological basis of case-based research in comparative studies as a point of departure, also highlighting the requirements in comparative research. In what follows, second, the chapter focuses on presenting and discussing recent developments in scholarship to provide insights on how comparative researchers, especially those investigating educational policy and practice in the context of globalization and internationalization, have suggested some critical rethinking of case study research to account more effectively for recent conceptual shifts in the social sciences related to culture, context, space and comparison. In a third section, it presents the approach to comparative case studies adopted in the European research project YOUNG_ADULLLT that has set out to research lifelong learning policies in their embeddedness in regional economies, labour markets and individual life projects of young adults. The chapter is rounded out with some summarizing and concluding remarks.

2 Case-Based Research in Comparative Studies

In the past, comparativists have oftentimes regarded case study research as an alternative to comparative studies proper. At the risk of oversimplification: methodological choices in comparative and international education (CIE) research, from the 1960s onwards, have fallen primarily on either single country (small n) contextualized comparison, or on cross-national (usually large n, variable) decontextualized comparison (see Steiner-Khamsi, 2006a, 2006b, 2009). These two strands of research—notably characterized by Development and Area Studies on the one side and large-scale performance surveys of the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) type, on the other—demarcated their fields by resorting to how context and culture were accounted for and dealt with in the studies they produced. Since the turn of the century, though, comparativists are more comfortable with case study methodology (see Little, 2000; Vavrus and Bartlett 2006, 2009; Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017) and diagnoses of an “identity crisis” of the field due to a mass of single-country studies lacking comparison proper (see Schriewer, 1990; Wiseman & Anderson, 2013) started dying away. Greater acceptance of and reliance on case-based methodology has been related with research on policy and practice in the context of globalization and coupled with the intention to better account for culture and context, generating scholarship that is critical of power structures, sensitive to alterity and of other ways of knowing.

The phenomena that have been coined as constituting “globalization” and “internationalization” have played, as mentioned, a central role in the critical rethinking of case study research. In researching education under conditions of globalization, scholars placed increasing attention on case-based approaches as opportunities for investigating the contemporary complexity of policy and practice. Further, scholarly debates in the social sciences and the humanities surrounding key concepts such as culture, context, space, and place but also comparison have also contributed to a reconceptualization of case study methodology in CIE. In terms of the requirements for such an investigation, scholarship commands an adequate conceptualization that problematizes the objects of study and that does not take them as “unproblematic”, “assum[ing] a constant shared meaning”; in short, objects of study that are “fixed, abstract and absolute” (Fine, quoted in Dale & Robertson, 2009, p. 1114). Case study research is thus required to overcome methodological “isms” in their research conceptualization (see Dale & Robertson, 2009; Robertson & Dale, 2017; see also Lange & Parreira do Amaral, 2018). In response to these requirements, the approaches to case study discussed in CIE depart from a conceptualization of the social world as always dynamic, emergent, somewhat in motion, and always contested. This view considers the fact that the social world is culturally produced and is never complete or at a standstill, which goes against an understanding of case as something fixed or natural. Indeed, in the past cases have often been understood almost in naturalistic ways, as if they existed out there, waiting for researchers to “discover” them. Usually, definitions of case study also referred to inquiry that aims at elucidating features of a phenomenon to yield an understanding of why, how and with what consequences something happens. One can easily find examples of cases understood simply as sites to observe/measure variables—in a nomothetic cast—or examples, where cases are viewed as specific and unique instances that can be examined in the idiographic paradigm. In contrast, rather than taking cases as pre-existing entities that are defined and selected as cases, recent case-oriented research has argued for a more emergent approach which recognizes that boundaries between phenomenon and context are often difficult to establish or overlap. For this reason, researchers are incited to see this as an exercise of “casing”, that is, of case construction. In this sense, cases here are seen as complex systems (Ragin & Becker, 1992) and attention is devoted to the relationships between the parts and the whole, pointing to the relevance of configurations and constellations within as well as across cases in the explanation of complex and contingent phenomena. This is particularly relevant for multi-case, comparative research since the constitution of the phenomena that will be defined, as cases will differ. Setting boundaries will thus also require researchers to account for spatial, scalar (i.e., level or levels with which a case is related) and temporal aspects.

Further, case-based research is also required to account for multiple contexts while not taking them for granted. One of the key theoretical and methodological consequences of globalization for CIE is that it required us to recognize that it alters the nature and significance of what counts as contexts (see Parreira do Amaral, 2014). According to Dale (2015), designating a process, or a type of event, or a particular organization, as a context, entails bestowing a particular significance on them, as processes, events, and so on that are capable of affecting other processes and events. The key point is that rather than being so intrinsically, or naturally, contexts are constructed as “contexts”. In comparative research, contexts have been typically seen as the place (or the variables) that enable us to explain why what happens in one case is different from what happens another case; what counts as context then is seen as having the same effect everywhere, although the forms it takes vary substantially (see Dale, 2015). In more general terms, recent case study approaches aim at accounting for the increasing complexity of the contexts in which they are embedded, which, in turn, is related to the increasing impact of globalization as the “context of contexts” (Dale, 2015, p. 181f; see also Carter & Sealey, 2013; Mjoset, 2013). It also aims at accounting for overlapping contexts. Here it is important to note that contexts are not only to be seen in spatio-geographical terms (i.e., local, regional, national, international), but contexts may also be provided by different institutional and/or discursive contexts that create varying opportunity structures (Dale & Parreira do Amaral, 2015; see also Chap. 2 in this volume). What one can call temporal contexts also plays an important role, for what happens in the case unfolds as embedded not only in historical time, but may be related to different temporalities (see the concept of “timespace” as discussed by Lingard & Thompson, 2016) and thus are influenced by path dependence or by specific moments of crisis (Rhinard, 2019; see also McLeod, 2016). Moreover, in CIE research, the social-cultural production of the world is influenced by developments throughout the globe that take place at various places and on several scales, which in turn influence each other, but in the end, become locally relevant in different facets. As Bartlett and Vavrus write, “context is not a primordial or autonomous place; it is constituted by social interactions, political processes, and economic developments across scales and times.” ( Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017, p. 14). Indeed, in this sense, “context is not a container for activity, it is the activity” (Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017, p. 12, emphasis in orig.).

Also, dealing with the complexity of education policy and practice requires us to transcend the dichotomy of idiographic versus nomothetic approaches to causation. Here, it can be argued that case studies allow us to grasp and research the complexity of the world, thus offering conceptual and methodological tools to explore how phenomena viewed as cases “depend on all of the whole, the parts, the interactions among parts and whole, and the interactions of any system with other complex systems among which it is nested and with which it intersects” (Byrne, 2013, p. 2). The understanding of causation that undergirds recent developments in case-based research aims at generalization, yet it resists ambitions to establishing universal laws in social scientific research. Focus is placed on processes while tracking the relevant factors, actors and features that help explain the “how” and the “why” questions (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017, p. 38ff), and on “causal mechanisms”, as varying explanations of outcomes within and across cases, always contingent on interaction with other variables and dependent contexts (see Byrne, 2013; Ragin, 2000). In short, the nature of causation underlying the recent case study approaches in CIE is configurational and not foundational.

This is also in line with how CIE research regards education practice, research, and policy as a socio-cultural practice. And it refers to the production of social and cultural worlds through “social actors, with diverse motives, intentions, and levels of influence, [who] work in tandem with and/or in response to social forces” (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017, p. 1). From this perspective, educational phenomena, such as in policymaking, are seen as a “deeply political process of cultural production engaged in and shaped by social actors in disparate locations who exert incongruent amounts of influence over the design, implementation, and evaluation of policy” ( Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017, p. 1f). Culture here is understood in non-static and complex ways that reinforce the “importance of examining processes of sense-making as they develop over time, in distinct settings, in relation to systems of power and inequality, and in increasingly interconnected conversation with actors who do not sit physically within the circle drawn around the traditional case” (Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017, p. 11, emphasis in orig.).

In sum, the approaches to case study put forward in CIE provide conceptual and methodological tools that allow for an analysis of education in the global context throughout scale, space, and time, which is always regarded as complexly integrated and never as isolated or independent. The following subsection discusses Comparative Case Studies (CCS) as suggested in recent comparative scholarship, which aims at attending to the methodological requirements discussed above by integrating horizontal, vertical, and transversal dimensions of comparison.

2.1 Comparative Case Studies: Horizontal, Vertical and Transversal Dimensions

Building up on their previous work on vertical case studies (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017; Vavrus & Bartlett, 2006, 2009), Frances Vavrus and Lesley Bartlett have proposed a comparative approach to case study research that aims at meeting the requirements of culture and context sensitive research as discussed in this special issue.

As a research approach, CCS offers two theoretical-methodological lenses to research education as a socio-cultural practice. These lenses represent different views on the research object and account for the complexity of education practice, policy, and research in globalized contexts. The first lens is “context-sensitive”, which focuses on how social practices and interactions constitute and produce social contexts. As quoted above, from the perspective of a socio-cultural practice, “context is not a container for activity, it is the activity” (Vavrus and Bartlett 2017: 12, emphasis in orig.). The settings that influence and condition educational phenomena are culturally produced in different and sometimes overlapping (spatial, institutional, discursive, temporal) contexts as just mentioned. The second CCS lens is “culture-sensitive” and focuses on how socio-cultural practices produce social structures. As such, culture is a process that is emergent, dynamic, and constitutive of meaning-making as well as social structuration.

The CCS approach aims at studying educational phenomena throughout scale, time, and space by providing three axes for a “studying through” of the phenomena in question. As stated by Lesley Bartlett and Frances Vavrus with reference to comparative analyses of global education policy:

the horizontal axis compares how similar policies unfold in distinct locations that are socially produced […] and ‘complexly connected’ […]. The vertical axis insists on simultaneous attention to and across scales […]. The transversal comparison historically situates the processes or relations under consideration (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017: 3, emphasis in orig.).

These three axes allow for a methodological conceptualization of “policy formation and appropriation across micro-, meso-, and macro levels” by not theorizing them as distinct or unrelated (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017, p. 4). In following Latour, they state:

the macro is neither “above” nor “below” the intersections but added to them as another of their connections’ […]. In CCS research, one would pay close attention to how actions at different scales mutually influence one another (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017, p. 13f, emphasis in orig.)

Thus, these three axes contain

processes across space and time; and [the CCS as a research design] constantly compares what is happening in one locale with what has happened in other places and historical moments. These forms of comparison are what we call horizontal, vertical, and transversal comparisons (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017, p. 11, emphasis in orig.)

In terms of the three axes along with comparison is organized, the authors state that horizontal comparison commands attention to how historical and contemporary processes have variously influenced the “cases”, which might be constructed by focusing “people, groups of people, sites, institutions, social movements, partnerships, etc.” (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017, p. 53) Horizontal comparisons eschew pressing categories resultant from one case others, which implies including multiple cases at the same scale in a comparative case study, while at the same time attending to “valuable contextual information” about each of them. Horizontal comparisons use units of analysis that are homologous, that is, equivalent in terms of shape, function, or institutional/organizational nature (for instance, schools, ministries, countries, etc.) ( Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017, p. 53f). Similarly, comparative case studies may also entail tracing a phenomenon across sites, as in multi-sited ethnography (see Coleman & von Hellermann, 2012; Marcus, 1995).

Vertical comparison, in turn, does not simply imply the comparison of levels; rather it involves analysing networks and their interrelationships at different scales. For instance, in the study of policymaking in a specific case, vertical comparison would consider how actors at different scales variably respond to a policy issued at another level—be it inter−/supranational or at the subnational level. CCS assumes that their different appropriation of policy as discourse and as practice is often due to different histories of racial, ethnic, or gender politics in their communities that appropriately complicate the notion of a single cultural group (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017, p. 73f). Establishing what counts as context in such a study would be done “by tracing the formation and appropriation of a policy” at different scales; and “by tracing the processes by which actors and actants come into relationship with one another and form non-permanent assemblages aimed at producing, implementing, resisting, and appropriating policy to achieve particular aims” ( Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017, p. 76). A further element here is that, in this way, one may counter the common problem that comparison of cases (oftentimes countries) usually overemphasizes boundaries and treats them as separated or as self-sustaining containers, when, in reality, actors and institutions at other levels/scales significantly impact policymaking (Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017).

In terms of the transversal axis of comparison, Bartlett and Vavrus argue that the social phenomena of interest in a case study have to be seen in light of their historical development (Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017, p. 93), since these “historical roots” impacted on them and “continues to reverberate into the present, affecting economic relations and social issues such as migration and educational opportunities.” As such, understanding what goes on in a case requires to “understand how it came to be in the first place.” ( Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017, p. 93) argue:

history offers an extensive fount of evidence regarding how social institutions function and how social relations are similar and different around the world. Historical analysis provides an essential opportunity to contrast how things have changed over time and to consider what has remained the same in one locale or across much broader scales. Such historical comparison reveals important insights about the flexible cultural, social, political, and economic systems humans have developed and sustained over time (Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017, p. 94).

Further, time and space are intimately related and studying the historical development of the social phenomena of interest in a case study “allows us to assess evidence and conflicting interpretations of a phenomenon,” but also to interrogate our own assumptions about them in contemporary times (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017), thus analytically sharpening our historical analyses.

As argued by the authors, researching the global dimension of education practice, research or policy aims at a “studying through” of phenomena horizontally, vertically, and transversally. That is, comparative case study builds on an emergent research design and on a strong process orientation that aims at tracing not only “what”, but also “why” and “how” phenomena emerge and evolve. This approach entails “an open-ended, inductive approach to discover what […] meanings and influences are and how they are involved in these events and activities—an inherently processual orientation” (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017, p. 7, emphasis in orig.).

The emergent research design and process orientation of the CCS relativizes a priori, somewhat static notions of case construction in CIE and emphasizes the idea of a processual “casing”. The process of casing put forward by CCS has to be understood as a dynamic and open-ended embedding of “cased” research phenomena within moments of scale, space, and time that produce varying sets of conditions or configurations.

In terms of comparison, the primary logic is well in line with more sophisticated approaches to comparison that not simply establish relationships between observable facts or pre-existing cases; rather, the comparative logic aims at establishing “relations between sets of relationships”, as argued by Jürgen Schriewer:

[the] specific method of science dissociates comparison from its quasi-natural union with resemblances; the interest in identifying similarities shifts from the level of factual contents to the level of generalizable relationships. […] One of the primary ways of extending their scope, or examining their explanatory power, is the controlled introduction of varying sets of conditions. The logic of relating relationships, which distinguishes the scientific method of comparison, comes close to meeting these requirements by systematically exploring and analysing sociocultural differences with respect to scrutinizing the credibility of theories, models or constructs (Schriewer, 1990, p. 36).

The notion of establishing relations between sets of relationships allows to treat cases not as homogeneous (thus avoiding a universalizing notion of comparison); it establishes comparability not along similarity but based on conceptual, functional and/or theoretical equivalences and focuses on reconstructing ‘varying sets of conditions’ that are seen as relevant in social scientific explanation and theorizing, and to which then comparative case studies may contribute.

The following section aims presents the adaptation and application of a comparative case study approach in the YOUNG_ADULLLT research project.

3 Exploring Landscapes of Lifelong Learning through Case Studies

This section illustrates the usage of comparative case studies by drawing from research conducted in a European research project upon which the chapters in this volume are based. The project departed from the observation that most current European lifelong learning (LLL) policies have been designed to create economic growth and, at the same time, guarantee social inclusion and argued that, while these objectives are complementary, they are, however, not linearly nor causally related and, due to distinct orientations, different objectives, and temporal horizons, conflicts and ambiguities may arise. The project was designed as a mixed-method comparative study and aimed at results at the national, regional, and local levels, focusing in particular on policies targeting young adults in situations of near social exclusion. Using a multi-level approach with qualitative and quantitative methods, the project conducted, amongst others, local/regional 18 case studies of lifelong learning policies through a multi-method and multi-level design (see Parreira do Amaral et al., 2020 for more information). The localisation of the cases in their contexts was carried out by identifying relevant areas in terms of spatial differentiation and organisation of social and economic relations. The so defined “functional regions” allowed focus on territorial units which played a central role within their areas, not necessarily overlapping with geographical and/or administrative borders.Footnote 1

Two main objectives guided the research: first, to analyse policies and programmes at the regional and local level by identifying policymaking networks that included all social actors involved in shaping, formulating, and implementing LLL policies for young adults; second, to recognize strengths and weaknesses (overlapping, fragmented or unfocused policies and projects), thus identifying different patterns of LLL policymaking at regional level, and investigating their integration with the labour market, education and other social policies. The European research project focused predominantly on the differences between the existing lifelong learning policies in terms of their objectives and orientations and questioned their impact on young adults’ life courses, especially those young adults who find themselves in vulnerable positions. What concerned the researchers primarily was the interaction between local institutional settings, education, labour markets, policymaking landscapes, and informal initiatives that together nurture the processes of lifelong learning. They argued that it is by inquiring into the interplay of these components that the regional and local contexts of lifelong learning policymaking can be better assessed and understood. In this regard, the multi-layered approach covered a wide range of actors and levels and aimed at securing compatibility throughout the different phases and parts of the research.

The multi-level approach adopted aimed at incorporating the different levels from transnational to regional/local to individual, that is, the different places, spaces, and levels with which policies are related. The multi-method design was used to bring together the results from the quantitative, qualitative and policy/document analysis (for a discussion: Parreira do Amaral, 2020).

Studying the complex relationships between lifelong learning (LLL) policymaking on the one hand, and young adults’ life courses on the other, requires a carefully established research approach. This task becomes even more challenging in the light of the diverse European countries and their still more complex local and regional structures and institutions. One possible way of designing a research framework able to deal with these circumstances clearly and coherently is to adopt a multi-level or multi-layered approach. This approach recognises multiple levels and patterns of analysis and enables researchers to structure the workflow according to various perspectives. It was this multi-layered approach that the research consortium of YOUNG_ADULLLT adopted and applied in its attempts to better understand policies supporting young people in their life course.

3.1 Constructing Case Studies

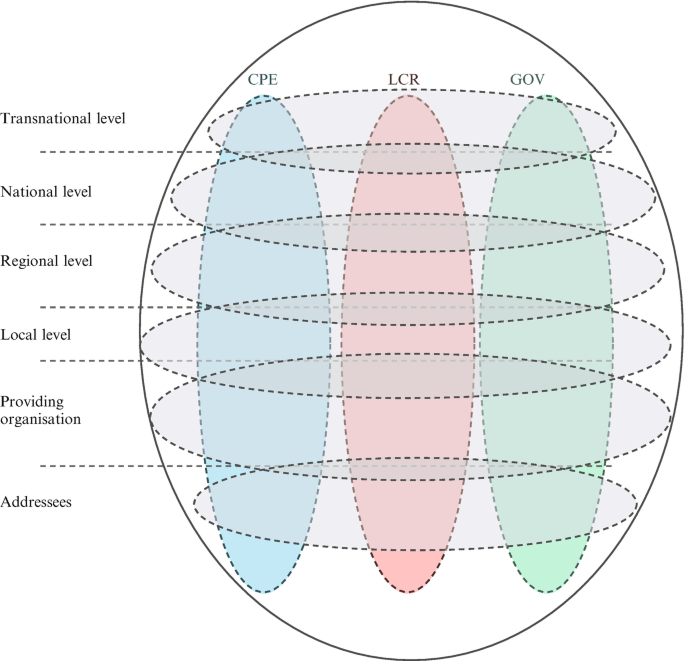

In constructing case studies, the project did not apply an instrumental approach focused on the assessment of “what worked (or not)?” Rather, consistently with Bartlett and Vavrus’s proposal (Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017), the project decided to “understand policy as a deeply political process of cultural production engaged in and shaped by social actors in disparate locations who exert incongruent amounts of influence over the design, implementation, and evaluation of policy” ( Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017, p. 1f). This was done in order to enhance the interactive and relational dimension among actors and levels, as well as their embeddedness in local infra-structures (education, labour, social/youth policies) according to project’s three theoretical perspectives. The analyses of the information and data integrated by our case study approach aimed at a cross-reading of the relations among the macro socio-economic dimensions, structural arrangements, governance patterns, addressee biographies and mainstream discourses that underlie the process of design and implementation of the LLL policies selected as case study. The subjective dimensions of agency and sense-making animated these analyses, and the multi-level approach contextualized them from the local to the transnational levels. Figure 3.1 below represents the analytical approach to the research material gathered in constructing the case studies. Specifically, it shows the different levels, from the transnational level down to the addressees.

Multi-level and multi-method approach to case studies in YOUNG_ADULLLT. Source: Palumbo et al., 2019

The project partners aimed at a cross-dimensional construction of the case studies, and this implied the possibility of different entry points, for instance by moving the analytical perspective top-down or bottom-up, as well as shifting from left to right of the matrix and vice versa. Considering the “horizontal movement”, the multidimensional approach has enabled taking into consideration the mutual influence and relations among the institutional, individual, and structural dimensions (which in the project corresponded to the theoretical frames of CPE, LCR, and GOV). In addition, the “vertical movement” from the transnational to the individual level and vice versa was meant to carefully carry out a “study of flows of influence, ideas, and actions through these levels” (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017, p. 11), emphasizing the correspondences/divergences among the perspectives of different actors at different levels. The transversal dimension, that is, the historical process, focused on the period after the financial crisis of 2007/2008 as it has impacted differently on the social and economic situations of young people, often resulting in stern conditions and higher competition in education and labour markets, which also called for a reassessment of existing policies targeting young adults in the countries studied.

Concerning the analyses, a further step included the translation of the conceptual model illustrated in Fig. 3.1 above into a heuristic table used to systematically organize the empirical data collected and guide the analyses cases constructed as multi-level and multidimensional phenomena, allowing for the establishment of interlinkages and relationships. By this approach, the analysis had the possibility of grasping the various levels at which LLL policies are negotiated and displaying the interplay of macro-structures, regional environments and institutions/organizations as well as individual expectations. Table 3.1 illustrates the operationalization of the data matrix that guided the work.

In order to ensure the presentability and intelligibility of the results,Footnote 2 a narrative approach to case studies analysis was chosen whose main task was one of “storytelling” aimed at highlighting what made each case unique and what difference it makes for LLL policymaking and to young people’s life courses. A crucial element of this entails establishing relations “between sets of relationships”, as argued above.

LLL policies were selected as starting points from which the cases themselves could be constructed and of which different stories could be developed. That stories can be told differently does not mean that they are arbitrary, rather this refers to different ways of accounting for the embedding of the specific case to its context, namely the “diverging policy frameworks, patterns of policymaking, networks of implementation, political discourses and macro-structural conditions at local level” (see Palumbo et al., 2020, p. 220). Moreover, developing different narratives aimed at representing the various voices of the actors involved in the process—from policy-design and appropriation through to implementation—and making the different stakeholders’ and addressees’ opinions visible, creating thus intelligible narratives for the cases (see Palumbo et al., 2020). Analysing each case started from an entry point selected, from which a story was told. Mainly, two entry points were used: on the one hand, departing from the transversal dimension of the case and which focused on the evolution of a policy in terms of its main objectives, target groups, governance patterns and so on in order to highlight the intended and unintended effects of the “current version” of the policy within its context and according to the opinions of the actors interviewed. On the other hand, biographies were selected as starting points in an attempt to contextualize the life stories within the biographical constellations in which the young people came across the measure, the access procedures, and how their life trajectories continued in and possibly after their participation in the policy (see Palumbo et al., 2020 for examples of these narrative strategies).

4 Concluding Remarks

This chapter presented and discussed the methodological basis and requirements of conducting case studies in comparative research, such as those presented in the subsequent chapters of this volume. The Comparative Case Study approach suggested in the previous discussion offers productive and innovative ways to account sensitively to culture and contexts; it provides a useful heuristic that deals effectively with issues related to case construction, namely an emergent and dynamic approach to casing, instead of simply assuming “bounded”, pre-defined cases as the object of research; they also offer a helpful procedural, configurational approach to “causality”; and, not least, a resourceful approach to comparison that allows researchers to respect the uniqueness and integrity of each case while at the same time yielding insights and results that transcend the idiosyncrasy of the single case. In sum, CCS offers a sound approach to CIE research that is culture and context sensitive.

Notes

- 1.

For a discussion of the concept of functional region, see Parreira do Amaral et al., 2020.

- 2.

References

Bartlett, L., & Vavrus, F. (2017). Rethinking case study research. A comparative approach. Routledge.

Béland, D., & Cox, R. H. (Eds.). (2011). Ideas and politics in social science research. Oxford University Press.

Byrne, D. (2013). Introduction. Case-based methods: Why we need them; what they are; how to do them. In D. Byrne & C. C. Ragin (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of case-based methods (pp. 1–13). SAGE.

Carter, B., & Sealey, A. (2013). Reflexivity, realism and the process of casing. In D. Byrne & C. C. Ragin (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of case-based methods (pp. 69–83). SAGE.

Coleman, S., & von Hellermann, P. (Eds.). (2012). Multi-sited ethnography: Problems and possibilities in the translocation of research methods. Routledge.

Dale, R., & Parreira do Amaral, M. (2015). Discursive and institutional opportunity structures in the governance of educational trajectories. In M. P. do Amaral, R. Dale, & P. Loncle (Eds.), Shaping the futures of young Europeans: Education governance in eight European countries (pp. 23–42). Symposium Books.

Dale, R., & Robertson, S. (2009). Beyond methodological ʻismsʼ in comparative education in an era of globalisation. In R. Cowen & A. M. Kazamias (Eds.), International handbook of comparative education (pp. 1113–1127). Springer Netherlands.

Dale, R. (2015). Globalisierung in der Vergleichenden Erziehungswissenschaft re-visited: Die Relevanz des Kontexts des Kontexts. In M. P. do Amaral & S.K. Amos (Hrsg.) (Eds.), Internationale und Vergleichende Erziehungswissenschaft. Geschichte, Theorie, Methode und Forschungsfelder (pp. 171–187). Waxmann.

Jameson, F. (1998). The cultural turn. Selected writings on the postmodern. 1983–1998. Verso.

Lange, S., & Parreira do Amaral, M. (2018). Leistungen und Grenzen internationaler und vergleichender Forschung— Regulative Ideen für die methodologische Reflexion? Tertium Comparationis, 24(1), 5–31.

Lingard, B., & Thompson, G. (2016). Doing time in the sociology of education. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 38(1), 1–12.

Little, A. (2000). Development studies and comparative education: Context, content, comparison and contributors. Comparative Education, 36(3), 279–296.

Marcus, G. E. (1995). Ethnography in/of the world system: The emergence of multi-sited ethnography. Annual Review of Anthropology, 24, 95–117.

McLeod, J. (2016). Marking time, making methods: Temporality and untimely dilemmas in the sociology of youth and educational change. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 38(1), 13–25.

Mjoset, L. (2013). The Contextualist approach to social science methodology. In D. Byrne & C. C. Ragin (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of case-based methods (pp. 39–68). SAGE.

Münch, S. (2016). Interpretative Policy-Analyse. Eine Einführung. Springer VS.

Palumbo, M., Benasso, S., Pandolfini, V., Verlage, T., & Walther, A. (2019). Work Package 7 Cross-case and cross-national Report. YOUNG_ADULLLT Working Paper. http://www.young-adulllt.eu/publications/working-paper/index.php. Accessed 31 Aug 2021.

Palumbo, M., Benasso, S., & Parreira do Amaral, M. (2020). Telling the story. Exploring lifelong learning policies for young adults through a narrative approach. In M. P. do Amaral, S. Kovacheva, & X. Rambla (Eds.), Lifelong learning policies for young adults in Europe. Navigating between knowledge and economy (pp. 217–239). Policy Press.

Parreira do Amaral, M. (2014). Globalisierung im Fokus vergleichender Forschung. In C. Freitag (Ed.), Methoden des Vergleichs. Komparatistische Methodologie und Forschungsmethodik in interdisziplinärer Perspektive (pp. 117–138). Budrich.

Parreira do Amaral, M. (2020). Lifelong learning policies for young adults in Europe: A conceptual and methodological discussion. In M. P. do Amaral, S. Kovacheva, & X. Rambla (Eds.), Lifelong learning policies for young adults in Europe. Navigating between knowledge and economy (pp. 3–20). Policy Press.

Parreira do Amaral, M., Lowden, K., Pandolfini, V., & Schöneck, N. (2020). Coordinated policy-making in lifelong learning: Functional regions as dynamic units. In M. P. do Amaral, S. Kovacheva, & X. Rambla (Eds.), Lifelong learning policies for young adults in Europe navigating between knowledge and economy (pp. 21–42). Policy Press.

Ragin, C. C., & Becker, H. (1992). What is a case? Cambridge UP.

Ragin, C. C. (2000). Fuzzy set social science. Chicago UP.

Rhinard, M. (2019). The Crisisification of policy-making in the European Union. Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(3), 616–633.

Robertson, S., & Dale, R. (2017). Comparing policies in a globalizing world. Methodological reflections. Educação & Realidade, 42(3), 859–876.

Schriewer, J. (1990). The method of comparison and the need for externalization: Methodological criteria and sociological concepts. In J. Schriewer & B. Holmes (Eds.), Theories and methods in comparative education (pp. 25–83). Lang.

Steiner-Khamsi, G. (2006a). The development turn in comparative and international education. European Education: Issues and Studies, 38(3), 19–47.

Steiner-Khamsi, G. (2006b). U.S. social and educational research during the cold war: An interview with Harold J. Noah. European Education: Issues and Studies, 38(3), 9–18.

Vavrus, F., & Bartlett, L. (2006). Comparatively knowing: Making a case for vertical case study. Current Issues in Comparative Education, 8(2), 95–103.

Vavrus, F., & Bartlett, L. (Eds.). (2009). Critical approaches to comparative education: Vertical case studies from Africa, Europe, the Middle East, and the Americas. Palgrave Macmillan.

Wiseman, A. W., & Anderson, E. (2013). Introduction to part 3: Conceptual and methodological developments. In A. W. Wiseman & E. Anderson (Eds.), Annual review of comparative and international education 2013 (international perspectives on education and society, Vol. 20) (pp. 85–90). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

do Amaral, M.P. (2022). Comparative Case Studies: Methodological Discussion. In: Benasso, S., Bouillet, D., Neves, T., Parreira do Amaral, M. (eds) Landscapes of Lifelong Learning Policies across Europe. Palgrave Studies in Adult Education and Lifelong Learning. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96454-2_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96454-2_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-96453-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-96454-2

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)