Abstract

This chapter introduces a process designed to support older individuals’ inclusion in technology and access to information. This process informed the development and dissemination of our technology artefact for providing information about local services to older South Africans. But essential baseline data of their cell phone use was lacking. In 2014, for the first self-funded study iGNiTe: Older Individuals’ Cell Phone Use and Intra/Intergenerational Networks, a questionnaire and qualitative interview questions were developed. Student fieldworkers were trained to obtain information and facilitate older individuals’ engagement with technology. Older participants (n = 128) completed the questionnaire, and qualitative data came from 52 participants. In 2017, we obtained funding and launched a second, broader project we-DELIVER: Holistic service delivery to older people by local government through ICTs―with its own logical framework. Older participants across research settings responded to a revised questionnaire (n = 302) and provided qualitative data, and student fieldworkers (n = 160) reflected on their interactions with the participants. The findings from both data-collection initiatives informed the development of the Yabelana (‘sharing of information’) ICT ecosystem (website, app and Unstructured supplementary service data code [USSD]), which was disseminated to older participants and stakeholders in a workshop and policy brief.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Cell phone technology

- Facilitation strategies

- Research process

- Social engagement

- Technology artefact

- Older south Africans

- Yabelana ICT ecosystem

1 Introduction

This chapter is set in the context of purposely stimulating the inclusion of older adults in all life domains, including technology (Annan, 1998; UNDP, 2018). Even though the inclusion of older persons is receiving attention internationally (Keating et al., 2021), the particular concern in a country such as South Africa is that older individuals’ interests are often disregarded as a priority because pressing social issues demand attention, as does the allocation of resources in redressing the unequal inheritances of a pre-1994 society, combating poverty, and dealing with the staggering impact of high youth unemployment (see Chap. 1; Westoby & Botes, 2020). Older South Africans’ proper inclusion in technology to access information and services frequently lags behind for various reasons but mostly because a basic understanding of how they use cell phone technology is underreported. To this end, we have made a concerted effort to gather information about older individuals’ cell phone use and to identify the social systems facilitating their use, not only for the purposes of designing and developing an appropriate technology artefact, but also beyond the aim of this book.

This book is based on the view that technology is a feasible option for enabling older persons to access service information. Some attempts have been made to propose cell phone design guidelines for older persons to foster significant uptake of technology in South Africa (Van Biljon & Renaud, 2016), and to identify challenges inhibiting their cell phone access and use (Van Biljon et al., 2013). Local studies have engaged older individuals in the design of technologies to support their health and well-being (Du Preez & De La Harpe, 2019). The few available qualitative studies of older South Africans’ subjective experiences of technology (cell phones, specifically) have revealed that they believe they lack the relevant basic skills and knowledge, and that they are hesitant about using cell phones (Steyn et al., 2018). Older persons’ perceived level of competence with such a device varies according to the complexity of the phone and its features, which limits their use (Leburu et al., 2018). They rely on assistance from others, particularly younger people, who are emotionally close and within reach, who have technical expertise, and who help older individuals unconditionally (Leburu et al., 2018; Roos & Robertson, 2019; Scholtz, 2015). Research has shown that older persons use cell phones to promote their personal safety and sense of control, to manage their daily routines, and stay connected with loved ones (Lamont et al., 2017; Steyn et al., 2018). They creatively apply relational strategies for using cell phones and navigating the social environment to address their needs.

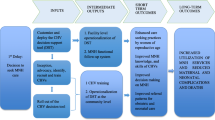

The process followed to develop a technology artefact aimed at enabling older individuals’ access to information is summarized in Fig. 3.1.

2 The Research Journey

The research journey was informed by the rationale for the development of the artefact; contextualization of the cohort of older individuals in the selected research communities and the participants’ situatedness in multigenerational families; and findings obtained from two data-collection initiatives. We adopted two key approaches to obtain findings that would guide the development of the artefact; and we employed social engagement facilitation strategies to support older persons’ optimal use of the technology and to disseminate it.

Rationale Chaps. 1 and 2 provided reasons for developing a technology artefact as a means to promote older South Africans’ access to service delivery. Chap. 1 positioned older individuals globally and within the southern African context. Chap. 2 identified service delivery problems against relevant legislative frameworks and concluded that technology could play an important role in enhancing older individuals’ access to services. Services are important because they provide opportunities for a decent life (Kelly & Westoby, 2018).

Contextualization The lack of information about older persons’ cell phone use motivated our research initiatives to collect baseline data. We obtained data from older participants in four communities, ranging from rural to urban, and we invited relevant stakeholders involved with service delivery to older individuals.

Data Collection and Findings We started gathering information about older South Africans’ cell phone use in 2014 through a self-funded study (iGNiTe), which gave us the opportunity to develop a questionnaire and draw up qualitative questions for semi-structured interviews and focus groups. In 2017, with funding from the Tirelo Bosha programme―a public service improvement programme and partnership between South Africa’s Department of Public Service and Administration (DPSA) and the Belgian Development Agency―we embarked on a larger-scale community-based project, entitled we-DELIVER: Holistic service delivery to older people by local government through ICT. The development of the iGNiTe and we-DELIVER questionnaires is discussed in Chap. 5. The findings of the quantitative analysis are presented in Chap. 6. We used insights obtained from student fieldworkers’ reflections and their participation in focus groups, with the data obtained from the older participants, to make recommendations for intergenerational programmes involving older and younger people in formal contexts in the public domain. The findings of this qualitative analysis are presented in Chap. 7.

Approaches Adopted We adopted two main approaches to drive the development of the Yabelana ecosystem. The first was ethical engagement, guided by two heuristics constructs to direct our ethical conduct—situatedness and relationality. Chap. 4 presents details of the phases followed and associated ethical actions in relation to the research team members themselves (researchers and student fieldworkers) and their interactions with older participants. The second approach was to use technology, with the facilitation of student fieldworkers, to collect and capture data from older participants about their cell phone use. A detailed discussion is presented in sect. 3.6 of this chapter and in Chap. 5.

Technology Artefact The rationale, contextualization and findings of the two data-collection initiatives informed the design and development of the Yabelana ICT ecosystem, consisting of a website, app and USSD code, presented in Chap. 8.

Social Engagement Facilitation Strategies We employed three strategies in the data collection and dissemination of the technology artefact: familiarity with sociocultural context; using dyads and small groups; and socializing. These are discussed in further detail in sect. 3.7 of this chapter.

Dissemination The Yabelana app and USSD code were introduced to older participants from the same communities who had participated in the we-DELIVER data collection, drawing on the same social engagement facilitation strategies. We invited representatives of the service delivery stakeholders to an experiential workshop and developed a policy brief.

3 Data-Collection Initiatives

The 2014 iGNiTe and the 2017 we-DELIVER data-collection initiatives used a context-specific approach towards the communities selected for the research as well as towards the stakeholders involved in delivering services to older individuals. We first describe the context, and then the two initiatives in turn.

3.1 Communities and Stakeholders in Context

Five communities in all (Potchefstroom, Promosa, Ikageng, Lokaleng and Sharpeville) that included rural and urban contexts, were the settings for the two data-collection initiatives. A rural setting refers here to a settlement that is not connected to a town or city, is sparsely populated and under traditional leadership. The urban settings represent large towns with higher-density developments near city centres or on the urban periphery (Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs, 2016).

3.1.1 Communities

The iGNiTe study included communities (Potchefstroom, Promosa and Ikageng) near the researchers and thus easily accessible. Three day-care settingsFootnote 1 for older persons in the large town of Potchefstroom (120 km southwest of Johannesburg) in South Africa’s North West province were purposively selected (see map in Fig. 3.2) for this first study.

The we-DELIVER project offered a broader scope. Owing to the time-limit of 18 months set by the funders to complete the study, three communities with existing links to the North-West University’s three campuses were purposively selected (see Preface): Lokaleng (Mahikeng Campus), Ikageng (Potchefstroom Campus), and Sharpeville (Vanderbijlpark Campus). They are situated in two provinces: Lokaleng, a rural setting, and Ikageng, a large town, are in North West, and Sharpeville, also a large town, is in Gauteng (see map in Fig. 3.2).

Population Composition and Household Income We extracted information about the older South Africans’ profile in relation to multigenerational households (HHs) for the five communities from national data (Stats SA, 2011): Potchefstroom, Promosa, and Ikageng (the locations of the iGNiTe study) and Lokaleng, Ikageng, and Sharpeville (the locations of the we-DELIVER project). The population composition and household income of the five research communities in the two data-collection initiatives are presented in Table 3.1. For the purpose of the multigenerational household structure, the population composition indicates people aged 65 yearsFootnote 2 and older and 14 years and younger. Household income includes the total number of households with no or low (less than R3,183 per month) income, and the 65 and older proportion of the households with no or low income. Population composition and household structure are presented in Table 3.2. It shows the male-female distributions of households, average number of people per household, and the number of households headed by people 65 years and older.

Multigenerational Household Trends The following trends are discussed as contextualization of the multigenerational household composition of the respective communities.

-

Potchefstroom: Of the population aged 15–64 years, 30% were aged 19–23 years because the town includes the Potchefstroom campus of the North-West University. In HHs with eight or more persons, people aged 65 years and older headed three out of a total of 72 (4%) households. The 65 years and older group headed 5% (n = 60) of the HHs comprising 5–7 members. In Potchefstroom there were 738 HHs headed by a grandparent or a great-grandparent; that is, 4% multigenerational households of all the HHs in the community. Of these, 87% (n = 642) included children aged 0–19 years.

-

Promosa: There were 231 (6%) multigenerational HHs headed by a grandparent or a great-grandparent, including 147 (64%) children aged 0–19 years. In Promosa there was an over-representation of multigenerational HHs in which people 65 years and older headed 19% (n = 36), with eight or more persons. The 65 years and older group headed 9% (n = 81) of HHs with 5–7 members.

-

Ikageng: If HHs with 8 or more persons are considered, we note that an over-representation of people 65 years and older headed 29% these; they also headed 17% of HHs with 5–7 members. Since this cohort represented 12% of the population of HH heads, it is clear that multigenerational households were more likely to be headed by individuals aged 65+ years. In Ikageng 1080 (4%) HHs were headed by a grandparent or a great-grandparent, including 609 (56%) children aged 0–19 years.

-

Lokaleng: 90 (13%) of all the HHs in Lokaleng were headed by people 65 years and older. People aged 65 years and older headed 12% of HHs consisting of eight or more persons, and 11% of HHs with between 5–7 members. In Lokaleng 60 (8%) multigenerational HHs including 42 (70%) children aged 0–19 years are headed by a grandparent or a great-grandparent,

-

Sharpeville: In HHs with eight or more persons, 43% were headed by people 65 years and older. Individuals in this age group also headed 28% of HHs with 5–7 members. This cohort (65+) represented 19% of the total population household heads and therefore clearly over-represented multigenerational-headed households. In Sharpeville 378 (3%) HHs were headed by a grandparent or a great-grandparent; of these, 40% (n = 150) included children aged 0–19 years.

3.1.2 Stakeholders

We identified three non-academic stakeholders relevant to promoting older individuals’ access to information and services: the South African Local Government Association (SALGA) (https://www.salga.org.za/), Age-in-Action, and South Africa’s DPSA.

-

SALGA is an independent association of municipalities whose mandate derives from South Africa’s Constitution. One of its main aims is to assist municipalities with policy guidelines in areas of community and human development. SALGA strives to determine how people’s different developmental stages are accommodated within the services and programmes that municipalities deliver, and to sensitize local governments to the limitations that certain age groups face—in this instance, older persons. We anticipated that SALGA’s involvement in our project could have a multiplier effect potentially, over time, influencing all local governments in the country’s nine provinces to use communications technology in promoting older individuals’ access to service-related information.

-

Age-in-Action is the largest NGO in South Africa that deals with the affairs of older individuals. It promotes the status, well-being, safety, and security of older persons, provides community-based care, and lobbies for older persons’ rights (http://www.age-in-action.co.za/).

-

The DPSA seeks to contribute to improving public administration and public service delivery through programmes, systems, frameworks, and research (http://www.dpsa.gov.za/about.php).

4 Self-Funded Study (2014)―iGNiTe: Older Individuals’ Cell Phone Use and Intra/Intergenerational Networks

The aim of this self-funded study was to design a new questionnaire for obtaining baseline data specifically about older individuals’ cell phone use; this information could subsequently be employed to monitor future cell phone use, and to customize ways to facilitate older participants’ engagement with technology. We used three data-collection methods, including visual data to obtain in-depth knowledge about older persons’ subjective experiences of using cell phones, and about any inter/intragenerational involvement in their use of the technology. For this purpose we developed qualitative interview questions.

4.1 Questionnaire

We designed the questionnaire relating to older persons’ cell phone use in sections that provided biographical and demographic data; information related to cell phone access, cell phone feature use, and competence to use a cell phone; and information about social networks pertinent to older persons’ cell phone use. Younger student fieldworkers administered the questionnaires, using technology as a method of application (see further discussion in sect. 3.6 below). The assessment of this questionnaire’s psychometric properties is discussed in Chap. 5.

4.2 Qualitative Data-Collection Methods

Three methods were used: semi-structured interviews, focus groups, and the Mmogo-method® for data collection based on visuals (Roos, 2008, 2012, 2016). Questions were formulated (see Box 3.1) for use both in the interviews and focus groups, to explore the subjective experiences of older persons in their intra/intergenerational interactions involving cell phone use.

Box 3.1 Questions for interviews and focus groups

-

What do you do with a cell phone?

-

Can you explain what role the cell phone plays in your relationships?

-

Whom do you ask for help when you struggle with your phone?

-

Why do you ask that specific person?

-

How did you experience the interaction when you asked for help?

The Mmogo-method® was employed to obtain the participants’ experiences specifically in relation to their cell phone use (Roos, 2008, 2012, 2016). The method is applicable across different sociocultural contexts (Puren & Roos, 2016) in four phases. Phase 1 consists of creating a clear context for the research, to clarify the research process and researchers’ expectations of participants, and to create a safe interpersonal space before introducing the research activities. We demonstrated empathy for the participants by recognizing that the research setting was unfamiliar as was using materials to visually express abstract experiences. We assured participants that their visual images or responses would be accepted unconditionally and emphasized voluntary participation and withdrawal from the research at any time they wanted to. In Phase 2, participants receive unstructured materials―such as malleable clay, beads of different colours and sizes, and dried grass stalks―and are asked to use the materials to construct visual representations. The open-ended prompt that we used in our project to stimulate the visual constructions was: “Please use the materials and make anything when thinking of your cell phone.” Participants completed their visual presentations in about 35 minutes. In Phase 3, participants are asked questions about the visual representations they have constructed. Phase 4 serves as a debriefing session for participants and researchers to exchange their experiences of participating in the data-collection method on the specific topic. In our study, it took place when the older participants and student fieldworkers enjoyed refreshments together and the fieldworkers offered support, if the participants needed it, to deal with any emotional reactions prompted by their engagement in the research.

The visual images were photographed to record the visual data, and individual and group discussions were transcribed for analysis as textual data. An example of an older woman’s visual representation is shown in Fig. 3.3. She had constructed a cell phone in relation to her desire to obtain an appropriate response to a need; she explained: “If you find the gates at home are locked, you can phone people inside the house to open the gate for you” (Ikageng, Participant 4).

4.3 Older Individuals’ Participation

The three data-collection methods used in iGNiTe yielded qualitative data from 52 older individuals: some participated by means of semi-structured interviews (n = 23), others through focus groups (n = 10), and a third group through the Mmogo-method® (n = 19). The questionnaires yielded quantitative data from older individuals (n = 128) with higher living-standard levels (see Chap. 6), explained partly by the fact that, on the day of data collection, some potential participants were prevented from attending the events owing to transport problems and child care responsibilities.

5 Funded Project (2017): we-DELIVER: Holistic Service Delivery to Older People by Local Government through ICT

With funding secured, this community-based project was initiated to expand the data on older individuals’ cell phone use and their service needs. The university provided an institution from which researchers in different subject disciplines could be recruited as well as a diverse group of student fieldworkers familiar with the different sociocultural contexts of the older persons in the targeted communities. The transdisciplinary research team consisted of researchers and student fieldworkers from disciplines that included demography and population studies, development studies, social work, psychology, language studies, law and public administration, biokinetics, and information systems. Such diversity benefits community-based research because it provides different subject disciplinary perspectives (see Tebes et al., 2014). In our study, it benefited the development of context-sensitive questionnaires, access to the different communities, and the older participants themselves. A logical framework consisting of an overall goal, specific objectives and activities, and verifiable indicators and assumptions guided the implementation of the we-DELIVER project (for details, see Table 3.3).

5.1 Revised Questionnaire

We revised and updated the earlier iGNiTe questionnaire to obtain baseline data of older individuals across a range of deprived rural settings as well as more urbanized and better resourced ones. The new questionnaire included the following sections relating to the participants and their cell phone use: biographical information, living standards, information related to the type of device used and connectivity, ability to use cell phone features, social and healthcare needs, relationships with those around them regarding cell phone use, and the level of participants’ self-perceived competence with cell phones (knowledge, skills, and attitude). A section on specific local service delivery needs was also included. Chap. 5 presents detail of the investigations into the questionnaire’s psychometric properties.

5.2 Qualitative Data

Qualitative questions were formulated for use in the semi-structured interviews and focus groups to address the goals of the we-DELIVER project (see Box 3.2).

Box 3.2 Questions for Interviews and Focus Groups

Cell Phones and Intra/Intergenerational Relations

-

Do you have access to a mobile phone?

-

If yes, ask: do you own the phone, or does it belong to someone else?

-

If it belongs to someone else, ask: to whom does it belong?

-

Are you using the phone yourself?

-

If someone is helping, ask:

-

Why do you ask that person to help you?

-

What do you ask them to help you with?

-

If asking for help from someone, determine if assistance is required in terms of the phone usage or in terms of challenges (physical, skills, knowledge?)

-

What kind of help do you ask for?

-

What kind of help do they give you?

-

-

If you struggle with the phone and don’t ask for help, can you explain why?

Older Persons’ Service Needs

-

As an older person, what kind of services do you need in order to live happily and well?

-

Where do you currently find the information/services you need?

-

Who provides these services?

-

If you need information, whom do you ask/call?

-

If your friend or neighbour asks you for information about issues regarding older persons, whom would you refer them to?

-

Do you ever use the phone to call the municipality to get information about things you need?

-

Does anybody else in your household use the phone to get information from the municipality about things you need?

Which of the following services do you need/use?

-

Welfare services (social grants): specific grants the older person has access to, e.g. old age pension, child support grant, foster care grant, disability grant.

-

Municipal/provincial/national health services; housing; police; public transport; child care facilities; electric services; storm water services; ambulance services; cultural matters; funeral parlours and cemeteries; municipal roads; refuse removal; street lighting.

5.3 Older Individuals’ Participation

Older individuals (n = 302) completed the questionnaire and results are reported in Chap. 6. For qualitative data collection, 198 people participated in focus groups (n = 22) and semi-structured interviews (14). The qualitative findings related to intra/intergenerational relations around older individuals and cell phones are reported in Chap. 7. Information about older individuals’ service needs was used to create the categories of service providers listed in the database of the technology artefact (see Chap. 8).

6 Approaches Adopted

Two approaches guided our data collection: ethical engagement and the use of technology for data capturing. Ethical engagement (discussed in Chap. 4) drew on two heuristic constructs, situatedness and relationality, and was applied in relation to the researchers, the student fieldworkers, and the participants. The present discussion focuses on the second approach, the use of technology in the data-collection process.

Technology was deliberately used during data collection to facilitate older individuals’ engagement. Before data collection commenced, we uploaded questionnaires on the cell phones of the student fieldworkers or on other mobile devices (Fig.3.4). Having established a relational connection with the participants (see Chap. 7 for details of the specific strategies applied), the fieldworkers invited the participants to respond to the questionnaire. Sitting close to one another, the participants could observe both the questions and how the student fieldworkers captured the responses on their mobile devices (see Fig. 3.5 and Fig. 3.6).

Because the fieldworkers knew how the questionnaire worked and how to use a mobile device, they used the technology to capture the older individuals’ responses accurately and efficiently, thereby limiting the time needed to complete the questionnaire, preventing potential participation fatigue, and modelling behaviour of comfortably engaging with technology.

7 Social Engagement Facilitation Strategies

The priority for the community-based project was: safe connections first before conducting research or using technology. We realized that for this particular cohort of older participants research was a most unfamiliar activity and involving them in topics related to their cell phone use or introducing a technology artefact could be perceived as threatening. According to Van der Kolk (2014), feeling unsafe causes people to seek social engagement to get help, support and comfort; it is in the interpersonal space that we send and search for cues of safety (Dana, 2018). Connecting safely to other people is not only fundamental to meaningful lives (see Van der Kolk, 2014) but also relevant when conducting research and introducing technology to a cohort of older individuals for whom both could be perceived as risky. The social engagement facilitation strategies used included drawing on the fieldworkers’ familiarity with the participants’ sociocultural context, working together in dyads and small groups, and socializing.

7.1 Familiarity with Sociocultural Context

We assumed that involving older individuals in a familiar relational context would contribute to feelings of safety in interpersonal interaction: it opens up the space for optimal engagement between people and reduces anxiety and reactivity (Levine, 2010; Porges, 2011).

We applied this facilitation strategy as follows: on the data-collection day, an older person or student fieldworkers who spoke the same vernacular as the older persons welcomed the older participants, introduced the event, and explained their involvement (Fig. 3.7). Student fieldworkers also familiar with the vernacular of the participants then captured their responses on mobile devices. Having a language in common acts as a proxy for sharing the same sociocultural context. We assumed that, in a familiar sociocultural context, a pre-existing cultural relationship between the participating older individuals and the younger student fieldworkers would be activated and that the interaction would progress according to the standard of behaviour established by the community’s culture (see Edwards, 2009; Hamington, 2010; Kaplan et al., 2017). According to principles of social constructionism, people learn to use symbols through the socialization process which “allow for smooth and effective interpersonal, intergroup, and intercultural communication” (Quist-Adade, 2019, p. 3). Therefore, involving older and younger people with shared knowledge of the sociocultural context in our project contributed to making the collaboration productive and to generating a shared understanding of ideas (see Damşa, 2014).

7.2 Dyads and Small Groups

Older participants and student fieldworkers paired off (Fig. 3.8) and in these dyads the fieldworkers engaged with the older individuals to obtain information about their cell phone use.

Later, the fieldworkers also engaged with small groups of older individuals to introduce the technology artefact, the Yabelana app and USSD code (Fig. 3.9) after it had been developed. Small groups more optimally promote participation according to Kelly and Westoby (2018). In our study, interactions in dyads and small groups took place after the student fieldworkers had created a warm inviting interpersonal context (see Chap. 7). The assumption guiding this social engagement strategy was that knowledge creation and meaning making are embedded in the mechanism of communicative interactional encounters with others, for example through dialogue, shared discourse, and conversational encounters (Damşa, 2014).

7.3 Socializing

On completion of data collection, the older and younger people socialized and enjoyed refreshments together (Fig. 3.10). Social settings in which people from different generations meet as individuals can serve to break down stereotypical ideas that each may have about the other and reduce barriers to communication (Chigeza et al., 2020; Roos, 2018).

8 Dissemination

Once the developed technology artefact (the Yabelana app and USSD code) was ready, it was introduced to the older persons in the three research communities of the we-DELIVER project and to representatives of the three groups of stakeholders.

8.1 Older Persons

Student fieldworkers introduced the Yabelana app and USSD code after establishing a relational connection with the participants, and supported the older persons with appropriate strategies for using the artefact to access information (see Chaps. 7 and 8).

8.2 SALGA and Age-in-Action

Formal training in the use of the Yabelana app and USSD code and its value in the context of service delivery to older individuals was provided to the stakeholders in the form of a two-day experiential knowledge-sharing workshop. Experiential learning was chosen as the preferred method of introducing the technology artefact that would enhance older individuals’ access to service information because we assumed that those attending would learn best by engaging actively in a learning process, as suggested by Everett and Bischoff (2021), complete with intended learning outcomes and real-world application. Attendees became further involved in the process as they reflected on their learning by presenting project proposals for applying Yabelana in service delivery, with clear time frames, dedicated activities, and assigned responsibilities.

The workshops provided information on using ICTs to improve holistic service delivery to older people by local government in five presentations, which covered:

-

Population ageing internationally and in South Africa, and the importance of ICT;

-

South African legislative guiding frameworks translated into practice;

-

Local Government Score Card: implementation and sustainability;

-

Community-based situational analysis (needs and resources);

-

Yabelana: using information and communication technologies.

The presentation of the workshops was based on the principles of the Ripples on a Pond (ROP) model as an enabling process for adult learning (Fivaz et al., 2011). We applied the model by inviting workshop attendees to listen to the five presentations with the aim of proposing a project for their local contexts. The ROP model proposed by Race (2010) is embedded in five overlapping processes: (1) creating a desire to learn; (2) taking ownership of the need to learn; (3) learning by doing (4); receiving and giving feedback; and (5) absorbing the learning. Our aim was to support workshop attendees in transferring the knowledge they had gained in the workshop to other contexts with a focus on enhancing service delivery to older individuals. Instructions given to the attendees are presented in Box 3.3.

Box 3.3

Instructions to Workshop Attendees to Support Active Learning

-

The assignment aims to assist attendees to take an active part in the workshops and to apply the information in practice.

-

At the end of the workshop, attendees will be invited to do a presentation in groups of no more than four by proposing a project with local relevance, to demonstrate application of the workshop information in practice.

-

The project presentation should include action plans, methods of application, and measures for obtaining feedback from older recipients.

8.3 Department of Public Service and Administration (DPSA)

We drafted a policy brief to share the research findings, presented in Box 3.4. A policy brief aims to translate evidence-based knowledge useful to policy makers as non-researchers who operate in a number of multiple levels of locality and governing (Siegel et al., 2021). The knowledge presented should be clear to enable policy makers to determine what solution would work under what conditions while considering rights and responsibilities (Romich & Fentress, 2019). The policy brief for this purpose contained a summary of the research findings with recommendations to assist DPSA to consider possible solutions to enhance older individuals’ access to services or to develop information and communication technology interventions using the technology artefact. The policy brief was developed using data from the we-DELIVER project.

Box 3.4

Policy brief. eDirectory Services (Yabelana) for Older South Africans by Local Government.

9 Conclusion

This chapter gives an overview of a research process that came full circle from planning and implementation of a community-based research project to writing this book. It presents the initiatives we applied (questionnaire development and data collection processes) to obtain a baseline understanding of older individuals’ cell phone use in relation to the specific research communities and the situatedness of the cohort of older South Africans who volunteered their participation. The knowledge we gained from the two data-collection initiatives informed the development of a technology artefact that offers service information and, through its dissemination, promotes older citizens’ inclusion in service delivery. The logical framework that guided our second community-based project provides suggestions for designing and mapping research to promote age-inclusivity. The inclusion of older individuals in research and technology is first and foremost about ethical relational conduct with a keen awareness of their contextual situatedness. Our experience of the process we employed leads to the recommendation for older persons’ involvement with technology to be more optimally facilitated than it has been in the past: in this instance, through the involvement of younger student fieldworkers, and by applying social engagement facilitation strategies. The research journey presented in this chapter sets the scene for the chapters that follow, which elaborate on special features of interest that were encountered along the way.

Notes

- 1.

Potchefstroom Service Centre for the Aged, Promosa Service Centre, and Ikageng Old Age centre.

- 2.

See footnote 2 in Preface on pg 5.

References

Annan K. (1998, October 1). UN International Conference on Ageing Press release. Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/press/en/1998/19981001.sgsm6728.html

Chigeza, S., Roos, V., Claasen, N., & Molokoe, K. (2020). Mechanisms in dynamic interplay with contexts in a multigenerational traditional food preparation initiative involving rural south African women. Journal of Intergenerational Relations, 18(4). https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2020.1732259

Damşa, C. I. (2014). The multi-layered nature of small-group learning: Productive interactions in object-oriented collaboration. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 9, 247–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-014-9193-8

Dana, D. (2018). The polyvagal theory in therapy. W.W. Norton & Company.

Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs. (2016). Integrated Urban Development Framework. https://iudf.co.za/knowledge-hub/documents/

Du Preez, V., & De La Harpe, R. (2019). Engaging aging individuals in the design of technologies and services to support health and Well-being: Constructivist grounded theory study. Journal of Medical Internet Research Aging, 2(1), e12393. https://doi.org/10.2196/12393

Edwards, S. D. (2009). Three versions of an ethics of care. Nursing Philosophy, 10(4), 231–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-769X.2009.00415.x

Everett, J. B., & Bischoff, M. (2021). Creating connections: Engaging student library employees through experiential learning. Journal of Library Administration, 61(4), 403–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2021.1906543

Fivaz, M., Herbst, A. G., Roos, V., & Hoffman, J. R. (2011). Social gerontology training in South Africa: A co-constructed learning environment. New Voices, 7(2), 84–98. http://reference.sabinet.co.za.nwulib.nwu.ac.za/sa_epublication_article/unipsyc_v7_n2_a7

Hamington, M. (2010). The will to care: Performance, expectation, and imagination. Hypatia, 25(3), 675–695. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2010.01110.x

Kaplan, M., Sanchez, M., & Hoffman, J. (2017). Intergenerational pathways to a sustainable society. Springer.

Keating, N., Eales, J., Phillips, J., Ayalon, L., Lazaro, M., Montes de Oca, V., Rea, P., & Tyagi, P. (2021). Critical human ecology and global contexts of rural ageing. In M. Skinner, R. Winterton, & K. Walsh (Eds.), Rural gerontology: Towards critical perspectives on rural ageing (pp. 52–63). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003019435

Kelly, A., & Westoby, P. (2018). Participatory development practice. Using traditional and contemporary frameworks. Practical Action Publishing.

Lamont, E., De Klerk, W., & Malan, L. (2017). Older age south African persons’ experiences of their needs with cell phone use. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 27(3), 260–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2017.1321854

Leburu, K., Grobler, H., & Bohman, D. M. (2018). Older people’s competence to use mobile phones: An exploratory study in a south African context. Geron, 17(3), 174–180. https://doi.org/10.4017/gt.2018.17.3.005.00

Levine, P. A. (2010). In an unspoken voice. How the body releases trauma and restores goodness. North Atlantic Books.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory. Norton.

Puren, K., & Roos, V. (2016). Using the Mmogo-method to explore important places and their meaning in two communities: The importance of context. In V. Roos (Ed.), Understanding relational and group experiences through the Mmogo-method® (pp. 195–212). Springer.

Quist-Adade, C. (2019). Symbolic interactionism: The basics. Vernon Press.

Race, P. (2010). Making learning happen: A guide for post-compulsory education. Sage.

Romich, J., & Fentress, T. (2019). The policy roundtable model: Encouraging scholar-practitioner collaborations to address poverty-related social problems. Journal of Social Service Research, 45(1), 76–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2018.1479343

Roos, V. (2008). The Mmogo-method®: Discovering symbolic community interactions. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 18(4), 659–668. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14330237.2008.10820249#.VGCob_noRs8

Roos, V. (2012). The Mmogo-method®: An exploration of experiences through visual projections. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 9(3), 249–261. http://www.tandfonline.com.nwulib.nwu.ac.za/doi/abs/10.1080/14780887.2010.500356#.VGC-t_noRs8

Roos, V. (2016). Conducting the Mmogo-method. In V. Roos (Ed.), Understanding relational and group experiences through the Mmogo-method® (pp. 19–31). Springer.

Roos, V. (2018). Facilitating meaningful communication among older adults. In M. A. Warren & S. I. Donaldson (Eds.), Toward a positive psychology of relationships new directions in theory and research (pp. 211–230). Praeger.

Roos, V., & Robertson, C. (2019). Young adults’ experiences regarding mobile phone use in relation to older persons: Implications for care. Qualitative Social Work, 18(6), 981–1001. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325018787857

South African Local Government Association (SALGA). https://www.salga.org.za/

Scholtz, S. E. (2015). Assistance seeking behaviour in older persons regarding the use of their mobile phones. Masters dissertation. North-West University (South Africa).

Siegel, J., Arenson, M., Mikytuck, A., & Woolard, J. (2021). Engaging public policy with psychological science. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 7(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000284

Stats SA (Statistics South Africa). (2011). Census 2011. Stats SA. https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P03014/P030142011.pdf

Steyn, S., Roos, V., & Botha, K. H. F. (2018). Cell phone usage relational regulation strategies of older south Africans. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 28(3), 201–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2018.1475911

Tebes, J. K., Thai, N. D., & Matlin, S. L. (2014). Twenty-first century science as a relational process: From Eureka! To team science and a place for community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology, 53(0), 475–490. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-014-9625-7

UNDP (2018). What does it mean to leave no one behind? A UNDP discussion paper and framework for implementation, United Nations Development Programme. Available at: www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/poverty-reduction/what-does-it-mean-toleave-no-one-behind-.html

Van Biljon J. and Renaud K. (2016). Validating mobile phone design guidelines: focusing on the elderly in a developing country. SAICSIT ’16: Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the South African Institute of Computer Scientists and Information Technologists 26–28 September, Article No.: 44, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1145/2987491.2987492.

Van Biljon, J., Renaud, K., & Van Dyk, T. (2013). Reporting on accessibility challenges experienced by South Africa’s older mobile phone users. The Journal of Community Informatics, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.15353/joci.v9i4.3148

Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The body keeps the score. Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin books.

Westoby, P., & Botes, L. (2020). Does community development work? Stories and practice for reconstructed community development in South Africa. Practical Action Publishing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Roos, V. (2022). Older South Africans’ Access to Service Delivery through Technology: A Process Overview. In: Roos, V., Hoffman, J. (eds) Age-Inclusive ICT Innovation for Service Delivery in South Africa. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94606-7_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94606-7_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-94605-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-94606-7

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)