Abstract

Similar to the concept of general well-being for individuals and societies, researchers have proposed various approaches to the concepts of personal beliefs and quality of life (QoL). In this chapter, QoL is discussed from an individual, subjective, cognitive and behavioral perspective with a focus on personal beliefs. More specifically, we present stress management as an endeavor in which yoga and personal beliefs can be applied to improve QoL. Stress management is recognized as a major health factor influencing an individual’s QoL. Empowered behavior to manage stress is discussed using a four-step model (involving thoughts, beliefs, emotions and behavior), that describes how human behavior is shaped by habits formed through individual experiences that unconsciously influence one’s thoughts, belief systems and emotions. Interventions such as yoga and meditation lead practitioners to question and alter thoughts in ways that can lead to improvements in QoL. Studies have indicated that when yoga and meditation are practiced regularly, the body implements stress-reducing processes automatically and unconsciously when a stressful situation arises. Therefore, this chapter contributes to the literature by demonstrating how yoga and meditation intervene in the mechanisms by which thoughts, beliefs and feelings shape behavior, as have been detailed in recent studies. In addition to the implementation of yoga and meditation, the possible use of technology and other tools for the quantitative assessment of states as a means of facilitating self-empowered behavior is discussed.

Do not believe in anything simply because you have heard it. Do not believe in anything simply because it is spoken and rumored by many. Do not believe in anything simply because it is found written in your religious books. Do not believe in anything merely on the authority of your teachers and elders. Do not believe in traditions because they have been handed down for many generations. But after observation and analysis, when you find that anything agrees with reason and is conducive to the good and benefit of one and all, then accept it and live up to it.

Buddha

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Personal beliefs

- Self-empowerment

- Yoga

- Meditation

- Thinking

- Behavior

- Mind

- Stress

- Happiness

- Heart rate pattern

- Emotions

- Coherent state

- Energetic heart

- Quality of life

- QoL

- Technology

Introduction

Quality of life (QoL) is defined for the purposes of this chapter along the World Health Organization (WHO) definitions as an individual’s physical and psychological health, their social relationships and the environment in which they live [1]. According to the criteria used in the Scales of General Well-Being (SGWB) questionnaire, the main contributing factors to an individual’s QoL are well-being criteria such as happiness, vitality, calmness, optimism, involvement, self-awareness, self-acceptance, self-worth, competence, development, purpose, significance, self-congruence and connection [2]. The importance of an individual’s spirituality and personal beliefs for their well-being, QoL and health status have been largely confirmed through numerous scientific studies [3, 4]. Personal beliefs are what an individual believes to be the truth, or the beliefs that define their individual worldview [5]. Additionally, individuals have a tendency to believe that others “feel, think and act” as they do [5]. Personal beliefs [6] are crucially linked to individual well-being and the individual’s “engagement to explore—and deeply and meaningfully connect one’s inner self—to the known world and beyond.” [7] This definition focuses on a personal search for meaning and exploration of QoL [7]. The definition provided by WHO the focuses on the “person’s personal beliefs and how these affect quality of life”.

Besides personal beliefs and their connection to a good QoL and happiness, this chapter also explores possibilities regarding self-empowered behavior change. Self-empowerment describes the way individuals “promote beliefs and attitudes favorable to deferring immediate reward for more substantial future benefit.”Footnote 1 [8] We consider behavior mainly as habit, or as an individual’s unconscious acts; therefore, producing a change in behavior involves repeated adjustment, as “changing behaviors is not about changing one act; it is about altering the routines in which the acts are embedded.” [9]

Another central component of personal-level QoL is the notion of happiness. Research has shown happiness to be a key aim for individuals [10, 11]. It has been widely shown that happiness plays a crucial role in the search for the meaning of life in religion and spiritual understanding, as well as in one’s personal beliefs (see also below). Numerous scientific studies have explored what makes individuals happy and the main factors for experiencing bliss, self-realization and QoL. However, there are important differences between how to be happy and what makes individuals happy [12]. In this chapter, happiness is defined as a constant positive feeling or subjective attitude towards one’s life [10,11,12] and is viewed on a continuum from happy to unhappy. This definition differs from others that define happiness as special moments where individuals feel bliss [10].

Happiness, as an essential component of QoL and well-being, does not only depend on the environment in which one lives. Individuals with enormous wealth and comfortable living conditions can be depressed, whereas others living in adverse conditions can manage their life circumstances to achieve a high degree of inner happiness [13,14,15,16,17,18]. Objective variables (e.g., income or lack of traumatic experiences) are far less significant determiners of happiness than intuition and the way one views their life experience [13,14,15,16,17, 19]. Indeed, social pressure and stress can occur when humans primarily consider happiness as a life achievement and unhappiness as a failure [20,21,22]. What is less clear, however, is how striving for happiness influences human belief systems [23,24,25,26,27].

In this chapter, we explore the role of thoughts, personal beliefs and emotions in the development of behavioral habits. Considering stress as an example of a factor influencing QoL that is shaped by one’s habits, we propose yoga and meditation as practices that can help individuals achieve self-empowerment by altering their thoughts, beliefs, emotions and, ultimately, their behaviors, thus resulting in a reduction of stress and an improvement in QoL. Furthermore, we discuss the potential use of technological devices and other tools for quantifying thoughts, beliefs, emotions and behaviors as a means of further empowering behavioral change.

The chapter is structured as follows. First, we provide a short overview of some relevant concepts such as the influence of stress and emotion on the human body and mind (Section “Stress and Emotions’ Influence on Psychophysiological Factors”). Second, adopting an interdisciplinary perspective, we explore how human behavior, and therefore QoL, is influenced by the mind (thoughts), by one’s belief in the thought and by the emotions produced by one’s thoughts (Section “Thoughts, Emotions, Beliefs and Behaviors”). Next, the chapter offers a discussion that can contribute to readers’ understanding of how stress-relieving techniques such as yoga and meditation can improve QoL by changing an individual’s thinking, emotions, beliefs and related behaviors (Section “Behavior: Yoga and Meditation as Interventions for Stress Management”). Specifically, yoga and meditation are explored as techniques to (1) observe thoughts (the mind), (2) separate beliefs from thoughts (personal beliefs) and (3) understand the connections that lead from a belief to a feeling (emotion) and (4) from a conscious or unconscious feeling to a behavior (behavior). Based on several case studies, we then suggest new technology-enabled ways of quantifying thought, belief, emotion and behavior that can be used by practitioners of yoga and meditation to assess the impact of their practice on these factors that influence QoL (Section “Quantifying Thoughts, Beliefs, Feelings and Behaviors”). The possibilities of self-empowered behavior change through yoga and meditation, as well as psychophysiological assessment tools, are discussed in section “Yoga and Meditation as Techniques for Achieving Self-Empowered Behavior”. Finally, a conclusion to the chapter is provided in section “Concluding Remarks”.

Stress and Emotions’ Influence on Psychophysiological Factors

Stress can be defined as “the non-specific response of the body to any demand made upon it.” [28] Individuals consider all subjective experiences to be either pleasant or unpleasant to some extent. Therefore, an individual’s subjective experience can have a very positive or very negative impact on their overall well-being, health and QoL [29]. The mechanisms of stressful thoughts leading to disease [28] are becoming an increasingly important field of scientific research. Studies have shown that an individual’s attitude towards stress plays a crucial role in their health and well-being. However, the absence of stress in one’s life can have an equally negative influence on one’s health as can an excess of stress, since only an adequate balance between the two generally leads to greater well-being [30].

Stress itself is not an emotion, although it is often created by certain feelings [31,32,33]. Emotions “typically unfold dynamically” [32] and “have a beginning and an end,” [32] whereas feelings are present for a longer period of time [32]. Humans usually distinguish positive and negative feelings as those that create emotions and impact the “fluidity or strain of life process(es).” [34] Often, feelings are considered to lead to negative emotions when they throw life out of balance and cause struggle. Feelings are regarded as producing positive emotions when life is harmonious, efficient and flowing [34]. Familiar patterns often allow life to continue smoothly, whereas changing patterns create an unfamiliar situation that “generates feelings and emotions.” [35] The emotions that have been evaluated most often in the psychological studies are presented in Table 12.1 [36], with each one categorized according to its valence (positive, negative or unassigned).Footnote 2 [37]

Although there are numerous studies that have demonstrated the difficulties involved in relating emotions to psychophysiological reactions in the human body [36], there are examples from the literature that provide persuasive evidence regarding particular correspondences between physiology and emotional states. In particular, the studies in the latter group indicate that, on the physical level, the body reacts to any situation in its environment that creates psychological flow or strain. For example, if one part of the body is changed or influenced by a situation, as in the case where one consciously slows down one’s breath, the other body parts (such as one’s heart rate) adapt to the new situation. This reaction is indicative of “synchronized interactions among multiple systems,” [38] other examples of which, relating to heart rate, are shown in Fig. 12.1 and explained further below.

Example of Emotions reflected in Heart Rhythm Patterns [39]

Overall, common repetitive behaviors, such as inactivity, poor nutritional habits and alcohol and tobacco consumption, may affect the way an individual manages daily life stress [40] and can determine up to 40% of the individual’s future health state and life quality [41]. Meanwhile, there are various psychophysiological factors that can be signs of stress (e.g., galvanic skin response, respiration, blood pressure and heart rate) [36]. In this section, we have chosen to discuss heart rate as a main indicator of stress, as it has been demonstrated that one’s heart rate responds directly to momentary emotional states [42]. While an abnormally low 24-hour heart rate can indicate increased risk of heart disease and premature mortality, it is also a strong marker of stress and emotions [43], as is shown in Fig. 12.1, and thus demonstrates the “synchronized interactions between different systems in the body” [44] alluded to above. It can be observed that heart rate patterns in particular—that is, the patterns of the curves rather than specific heart rate values—often directly reflect and synchronize with an individuals’ emotional states [44].

Furthermore, the analysis of heart rate and heart rate pattern provides an indicator of neurocardiac fitness and autonomic nervous system function [42]. Some studies have even found that heart rate pattern “covaried with emotions in real time.” [44] As heart rate patterns often directly reflect emotional states, various techniques to reduce stress, such as meditation techniques, produce specific heart rate patterns; in particular, such techniques have been found to produce a coherent, fine, smooth, “wave-like-pattern in the heart rhythms.” [45] Scientists have also found that a person practicing a technique to maintain positive emotional feelings displays heart rhythms that are synchronized with their brainwaves influenced by their emotional states (see Figs. 12.2 and 12.3). In comparison with individuals who experience a high degree of stress, those who apply such techniques also exhibit more regular and stable heart rate patterns.

Image of Dissonant Heart and Brainwave Rhythm [46]

Image of Heart Rhythm and Brainwaves in sync during a Meditative State [47]

Recent research has revealed that the body is also able to develop coherence or synchronization with the physiological processes of others. For instance, a mother thinking about her in utero baby can lead to the synchronization of her brainwaves with her baby’s heartbeat [48]. It has also been shown that couples that have lived together for many years can have coherent heart rate patterns while they sleep [49].

To summarize this section, we observe that there is a synchronization between brain and cardiac activities [50, 51]. There is particular evidence of a relation between heart rate patterns and positive and negative emotions [42]. Additionally, body stress regulation techniques enable a more regular and stable heart rate pattern.Footnote 3

Thoughts, Beliefs, Emotions, and Behaviors

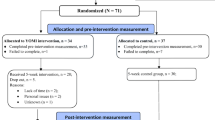

Behavior can be defined as “the internally coordinated responses (actions or inactions) of whole living organisms (individuals or groups) to internal and/or external stimuli.” [54] As indicated in the conceptual model presented in Fig. 12.4, behavior is influenced by (a) thoughts, (b) belief in thoughts and (c) feelings affected by beliefs and (d) decisions motivated by feelings [55]. Behavior can be influenced by “individual-level attributes as well as by the conditions under which people live.” [62] Thus, human behavior depends on the context in which it takes place [63]. Additionally, some studies state that as much as 99.9% of the decisions made by humans are shaped by other people [64]. Bargh provides further evidence of environmental influences on human behavior, stating that “our psychological reactions from moment to moment… are 99.44% automatic.” [65] Therefore, in order to better understand how an individual makes decisions, one needs to observe them within their natural environment [66] and consider contextual factors, as is indicated in Fig. 12.4. This principle must be applied when one is assessing the influence of human thinking on individual belief systems and emotions, leading to behaviors.

As mentioned above, this chapter considers behavior in relation to stress-management. In section “Stress and Emotions’ Influence on Psychophysiological Factors”, it was seen that emotions and feelings represent an important factor in stress management. The model presented in Fig. 12.4Footnote 4 conceptualizes the steps by which an individual adopts a behavior that can either increase or reduce stress, beginning with a change in one’s thoughts, beliefs or feelings.

The Influence of the Mind on Human Behavior

Corresponding to the first circle (Thought) in Fig. 12.4, thoughts are related to “one’s own individual experience.” [67] Most psychological research on decision-making over the past 30 years has focused on the logic of rational, controlled decisions (i.e., the logic behind behaviors). While logical mechanisms may describe the decision-making processes of scientific pursuits, their analysis is less appropriate for understanding the uncontrolled aspects of humans’ ordinary changes in behavior, which are based on both thoughts and feelings [56]. According to Baumeister et al., “it is plausible that almost every human behavior comes from a mixture of conscious and unconscious processing.” [60] This also means that a description of one’s conscious thoughts alone (or unconscious thoughts alone) is rarely sufficient to explain a specific behavior.

The mind, defined for the purposes of this chapter as an individual’s collected thoughts and cognition, is one of the great influencers of behavior [68]. According to scientists such as Anderson, if someone envisions an action, it leads to an “increased intention to do it” [69] and therefore a greater chance that the action will be achieved. According to Tiller, meanwhile, individuals can influence their future with their thoughts in the form of intentions [57]. The systems of thinking, or personal beliefs, that affect one’s intentions begin to be developed in one’s youth through imitation of parents, relatives, teachers and figures in media, among others. The information one gains in the process serves to “structure that person’s understood world and purposive ways of coping in it.” [70] When an individual is confronted with a choice, they unconsciously call upon all the past experiences that have been collected and registered in their brain, recalling them as thoughts. This process has been widely studied in psychology as the “theory of planned behavior.” [71, 72]

The effect of one’s state of mind, including one’s thoughts, on the outcome of a task has been demonstrated in a study by Armor and Taylor. In this study, the authors assessed how implemental and deliberative mindsets—the former characterized by plans and thoughts regarding how to implement an action, and the latter by questions concerning the merits of the action—respectively influenced one’s performance of a task. As the authors observed, “it appears that the simple difference in perspective that mindsets create—from the uncertain query ‘Will I do X?’ to the agentic assertion ‘I will do X’—can yield substantial differences in how the considered action will be perceived and, subsequently, acted on.” [73] The authors concluded that the expected results of a task, as well as one’s predictions regarding one’s own performance, “become less favorable following deliberation and more favorable following thoughts of implementation.” [73, 74]

Additionally, results from various studies have indicated that individuals adopting the perspective of another, as opposed to simply discussing a situation from their own perspective, can be a successful strategy for producing behavioral change [75,76,77].

In summary, the mind significantly influences behavior across multiple dimensions. As is seen above, the mind retains past experiences that may be triggered by external impulses. These experiences consciously and unconsciously influence the ways individuals think, shaping their beliefs, emotions and actions. In the next subsection, we will explore how beliefs (and unbelieves) can influence human behavior.

Influence of Personal Beliefs on Human Behavior

The second circle of Fig. 12.4, corresponding to beliefs, represents a step in the process leading to behavior in which an individual evaluates whether they believe a thought or not. A belief is not necessarily true; it is simply what an individual believes and claims to be true or false or right or wrong. It is also important to note that not all an individuals’ beliefs are derived from their own experience or thinking. As Barth et al. observes, “we all extend the reach and scope of our knowledge immensely, relying on judgements based on whatever criteria of validity we embrace—above all, what others whom we trust tell us they believe.” [59]

What an individual hears and considers to be true will have a profound and long-lasting influence on their behavior. As Geraerts et al. have demonstrated, even “the false suggestion of a childhood event can lead to persistent false beliefs that have lasting behavioral consequences.” [58] To illustrate this fact, the authors conducted a study where they informed subjects that they had become ill during childhood after eating egg salad. During the period immediately after receiving this false information, and even four months later, these subjects tended to avoid eating egg salad, whereas the control group continued to eat it as usual [58].

The personal belief system that leads to such behaviors is useful, and in some cases it can serve to protect one from harm or save one’s life. This is especially important in dangerous situations, where one needs to quickly judge and react, often as part of a fight or flight response [78]. However, making quick judgements of this sort in a broader context may become problematic when an individual does not question their thoughts and beliefs and assumes that their thinking always captures the truth. These individuals might cling to their beliefs because of the familiar feeling that one experiences when the mind recognizes a situation [59]. In such cases, these feelings unconsciously lead the individual to make decisions based on their previously stored knowledge or beliefs, or “what a person employs to interpret and act on the world.” [59] However, if such an individual explores the ways they can alter their personal belief system and its impact on their behavior [79], they can ultimately achieve better QoL, especially in areas—such as physical activity, nutrition and sleep—that contribute to their health later in life [80,81,82,83].

An important example of personal beliefs includes stereotypes about the differences between different cultural, ethnic and religious groups. Such beliefs, which derive from one’s one cultural, religious or social context, are often challenged when individuals from stereotyped groups behave in ways that are unexpected. The practice of sharing beliefs between members of different cultural, ethnic and religious groups can lead to confidence-creating emotions which enable individuals to easily create relationships, as well as a willingness to cooperate with others [84, 85].

Spirituality, as a cultural concept, also significantly influences an individual’s beliefs [86]. Scientific research has attempted to measure spiritual well-being using scales, the most common of which are the Spirituality Index of Well-Being, the Spirituality Scale, and the Daily Spiritual Experience Scale.Footnote 5 These scales assess spirituality using elements which ask the individual about their beliefs.Footnote 6

Similar to spirituality, relaxation methods aim to help individuals manage stress through practices that affect one’s personal beliefs. Many proposed methods for reaching a stress-free mental state include guidelines that instruct readers in changing their behavior. These guidelines are often meant to encourage hopeful, optimistic beliefs and feelings of inner peace [87]. Some methods recommend practices such as sitting down every morning to meditate [88] or drinking a cup of lukewarm water before eating [89]. While adopting these behaviors may be effective for some individuals, not everyone will be able to attain from them the change in stress-reduction or health-improvement that they desire. Various approaches and techniques of teaching have therefore been developed, allowing each individual to determine what works best for them and what is most appropriate in specific situations [90].

In the health context, meanwhile, it has been demonstrated that healing beliefs can play an important role in health outcomes. Healing beliefs are a conscious and mindful determination one makes to improve one’s health, or an expectation that one’s health and well-being are going to improve and that one will live a meaningful, productive life. Healing beliefs are a way of understanding and giving meaning to illness and suffering through the continued belief that the patient will achieve healing and well-being [91].

Additional studies in this area have found that health expectancy (one’s personal belief regarding future health outcomes) is an important part of healing processes, especially when there is a close relationship between the healer and the patient [92]. Studies have demonstrated that a healer’s capacity to self-heal tends to have a positive influence on a patient’s health outcomes. As Schmidt notes, “practicing loving kindness and compassion toward oneself helps develop these qualities in our relationship with others.” [93] The self-healing capacity may be observed by the patient unconsciously, stimulating the patient to use the same skills to heal themself.

In conclusion, there are many studies that demonstrate the impact of personal beliefs on individual behavior. More important than the act of changing one’s mind (one’s thoughts) in order to bring about behavioral change is changing one’s belief of this thought. This occurs on both a conscious and an unconscious level. The next subsection explores the influence of emotions on behavior, especially of those emotions that arise from beliefs.

The Influence of Emotions on Human Behavior

As is shown in Fig. 12.4 , believing a thought can create certain feelings in individuals that ultimately influence behavior. Feelings and emotions are interdependent. As mentioned in section “Stress and Emotions’ Influence on Psychophysiological Factors”, feelings produce emotions and last for a longer time than emotions, which always have a beginning and an end. Emotions influence behavior because an individual is more likely to do something if it is pleasurable and not stressful or if the outcome feels positive [94]. On the other hand, research shows that “anticipated emotion, especially anticipated regret, has been shown to motivate people and change behavior.” [60] Both examples illustrate how varied emotions, from positive emotions such as love to negative emotions such as fear, affect human behavior and supply important impulses for actions.

A wide range of theoretical models of behavior have been proposed that demonstrate how behaviors leading to long-term improvements in health and QoL, such as exercise and nutritional practices, can be implemented and adopted [95]. According to these models, individuals have the ability to adopt an alternative perspective or state of mind by altering their thoughts and personal beliefs, ultimately influencing their own emotions and leading to new behaviors. According to a recent study,Footnote 7 mood is a factor that has a major influence on how effectively individuals are able to improve their behavior. Moods, which are defined here as states or frames of mind, can last for a brief moment or be present during longer periods [32, 97]. Individuals in a negative mood have been found to exhibit less attention and concentration on tasks than those in a positive frame of mind and to ultimately deliver worse results. Individuals in a negative mood have also exhibited particular difficulty adapting to tasks again after being distracted by their own thoughts. These results demonstrate that those in a negative mood commit more behavioral lapses when engaged in a task, have “task-irrelevant thoughts” with more frequency and exhibit less motivation towards attentional commitments than those in a positive mood [96]. Meanwhile, a positive mood has been found to help individuals adapt to a task after a lapse [97].

A similar study concerning the impact of emotions on behavior has confirmed that emotions have a major influence in this regard (Fig. 12.5) [98]. According to Avey et al., individuals in a positive mood were not only better able to control their own behavior, but were also able to spread positivity to those around them. Their results demonstrate that one individual’s positive mood can even influence f.ex. employees in an organizational structure. More specifically, the individual’s mood was found to influence their own psychological capital, especially in the areas of hope, efficacy, optimism, resilience and mindfulness, by facilitating relationships and positive emotions, which led in turn to changes in the behavior of the surrounding individuals [99].

The effects of induced mood on the frequency of attentional lapses [96]

When describing the impact of emotions on behavior, it is important to also consider how the way one is received or treated in one’s surroundings affects emotional responses and, ultimately, behavior. Positive and negative feedback from one’s environment, for instance, have been found to affect an individual’s emotions in ways that influence behaviors such as “counterproductive behavior, turnover intentions, citizenship, and affective commitment.” [100]

In summary, there is significant evidence regarding the influence of emotions on an individual’s behavior. This influence can be seen in the effects of mood on task performance, the impact of positive and negative feedback on behavioral change and the capacity of individuals to spread positivity and alter the behaviors of others, examples that demonstrate the crucial role emotions play in behavior choice and change.

Behavior: Yoga and Meditation as Interventions for Stress Management

Given the above discussions concerning the influence of the mind, belief of thoughts and emotions on behavior, this section presents behavior techniques, particularly those of yoga and meditation, that have been found in research to help reduce stress through changes to an individual’s thoughts, beliefs and emotions that lead to behavioral change [101]. Nowadays, yoga and meditation are practiced worldwide to reduce stress and achieve life satisfaction [1032,1033,104]. Yoga and meditation techniques are claimed to be especially effective at helping practitioners (1) observe their thoughts (thought), (2) disconnect beliefs from thoughts (belief), (3) understand the connection between personal beliefs and feelings (emotion) and (4) recognize how conscious or unconscious feelings lead to a behavior (behavior).Footnote 8

In this chapter, yoga is defined as “an ancient practice with origins in India, […] incorporat[ing] muscle stretching, muscle relaxing, balancing poses (asanas), breathing (pranayama), guided relaxation, and/or meditation (dhyana) to achieve harmony and spiritual growth.” [105, 106] It is a culturally based tool that can become an integrated habit in one’s life [107]. A key aspect of yoga and meditation is a concept of embodiment that is focused on self-creation, as “control of the self is a project internal to the person rather than imposed by others, and modern persons actively define themselves through lifestyle choices, rather than being passively defined by their membership in traditional groups and moral orders.” [108]

Research on the mindful body, which is an approach to the body that treats mental and physiological processes as aspects of an integrated whole, has revealed significant insight into the effect of emotions, passions and conversational practices on behavioral outcomes. As yoga and meditation seek to alter behavior through deliberate changes to one’s emotions, such findings are highly relevant to the analysis of yoga presented in this chapter [109, 110]. Meanwhile, yoga psychology is a field of research and practice focusing on the use of yoga as a psychological tool that integrates behavioral and introspective approaches to facilitate an individual’s growth [111]. Several studies have revealed benefits of practicing yoga for a certain period of time. On a psychological level, yoga has been shown to improve emotional functioning [112] and reduce negative emotions in breast cancer patients [113]. In addition, studies of embodied cognition have demonstrated that yoga “may reduce stress by affecting the way individuals appraise stressors.” [114] One study has also found that regular practitioners of yoga react to negative emotional stimuli in such a way that it “does not have downstream effects on [their] later mood state.” [115]

On a physical level, yoga reduces stress by stimulating exchange and harmonization between the body and the mind. One of the parts of the human anatomy most responsible for communication between body parts is the nervous system, particularly the vagus nerve, which corresponds to the central energy channel called “Sushumna Nadi ” in yoga [116]. According to experts, the vagus nerve communicates information mainly from the heart, gut and other organs to the brain [117]. This nerve is stimulated in all yoga postures, or asanas [118, 119]. Yoga practices are based on a distinction between the two sides of the body: the left, called “Ida,” which is feminine and lunar, and the right, called “Pingala ,” which is masculine and solar. The aim of yoga is to unite both sides within the Sushumna Nadi or vagus nerve. When the body has been trained to slow its processes using the breath (e.g., via yoga), the heart rate automatically slows down when the individual is at rest. Neurological signals are transmitted from the brain to the heart and other organs via the vagus nerve without any change in the breath being necessary [120].

As is defined above, meditation is part of yoga practice. Meditation is defined as “practices that self-regulate the body and mind, thereby affecting mental events by engaging a specific attentional set.” [121] Meditation, like yoga, is considered a health-improving tool, and has been linked to numerous health benefits, such as reductions in pain sensation, short-term increases in blood pressure and improvements to respiratory efficiency, fluid exchange, cardiovascular system capacity and synchronization of the cells [122]. In a study of the efficacy of meditation techniques for treating medical illnesses, Arias et al. reported that “the strongest evidence for efficacy was found for epilepsy, symptoms of the premenstrual syndrome and menopausal symptoms. Benefit was also demonstrated for mood and anxiety disorders, autoimmune illness, and emotional disturbance in neoplastic disease.” [123] As Ospina et al. have observed in their survey of meditation research, the effects of meditation include physiological changes such as the reduction of the heart rate, blood pressure and cholesterol. On the neurophysiological side, meditation was also found to increase verbal creativity [124].

The calm mental states reached by practicing mindful meditation have been shown to impact the brain and emotions. As Hayes and Davis note, “There is evidence that mindfulness helps develop effective emotion regulation in the brain.” [121,122,123,128] The calm mental states associated with meditation can facilitate coherence or synchronization between bodily functions.Footnote 9 Coherence tends to produce a sense of peace of mind and emotional balance that increases overall well-being [122] and QoL. The coherence of different psychophysiological functions can be developed through training such that the body, without specific stimulation, later applies these trained techniques unconsciously [129]. A meditation practice that has provided particularly effective for the achievement of calm mental states is Transcendental Meditation. Research on this method has focused especially on its relationship to stress reduction, decreased depression, reduced anxiety and improved sleep quality [126,127,132]. Other studies, however, have shown that more desirable psychological states can be achieved with the practice of yoga paired with meditation, especially in cases of burn-out syndrome, depression and mental disorders [133, 134].

The Center for Healthy Minds, led by Professor Richard Davidson at the University of Wisconsin–Madison,Footnote 10 has stated, after many years of research on the topic, that well-being is a set of skills that can be learned in a way similar to playing the guitar. According to the results of their research, regular meditation can rewire areas of the brain [135] so that, although negative experiences from daily life are recognized, they affect individuals’ brain health, thoughts, emotions and actions for a much shorter time than they do for individuals who are not trained to meditate.Footnote 11

As indicated in the previous section, several studies [136] have demonstrated that positive emotions can positively influence human behavior, health and overall well-being [45]. A key factor in this process is the cultivation of coherence between emotional and bodily states. If an individual regularly practices a meditation technique that draws attention to positive emotions (such as Loving-Kindness Meditation [137]) or other techniques that are viewed as stimulating positive emotions (such as progressive muscle relaxation [136]), the body system establishes a habit. Research results indicate [134,135,140] that past experience “builds within us a set of familiar patterns, which are instantiated in the neural architecture.” [141] These patterns manifest as habits that are automatically enacted, even when the person is not actively practicing any meditation technique. External stimuli are then managed by the brain as perceptions, which automatically give rise to habitual feelings and behaviors [141]. According to one study, “the system then strives to maintain [positive emotional habits] automatically, thus rendering coherence a more readily accessible state during day-to-day activities, and even in the midst of stressful or challenging situations.” [122] In frequent meditators, stress responses are often automatically reduced the moment stress is experienced [142]. Interestingly, not every meditation technique leads to coherence between different body functions. Techniques that concentrate on positive emotions, for example, have been found to be more successful at facilitating coherent states than those that focus on the mind and thoughts (such as concentrative meditationFootnote 12) [122]. Therefore, one may assume that integrating the emotions into one’s meditation practices, rather than merely concentrating the mind on a given object, can result in more effective physiological and psychological functioning.

The approach to changing behavior through the cultivation of positive emotions is also considered in the understanding of impacts of yoga and meditation. According to the self-development perspective on behavioral change, the only way to change one’s behavior is from within oneself [143, 144]. Individuals may need help from outside sources, such as other humans or their external conditions, but managing one’s behavioral changes is the responsibility of each individual. This is also confirmed by the results of research on intrinsic behavior change and motivation. Self-determined motivation in particular, an attitude which yoga training aims to cultivate and draw on, has been found to have a direct effect on behavior [145].

Both yoga and meditation are promising tools that can influence well-being and QoL by changing one’s relation to one’s thoughts, personal beliefs, feelings and emotions and behavior (as conceptualized in Fig. 12.4). Results from a variety of studies have confirmed these benefits; nevertheless, the exact mechanism by which meditation affects QoL is still unclear. It is known that meditation influences cognitive processes; however, there are other factors that also influence well-being [146], such as “cultural differences, socioeconomic status, health, the quality of interpersonal relations, and specific psychological processes.” [146]

In summary, the current state of research indicates that yoga and meditation can be helpful techniques for individuals to observe their own thoughts and make sense of the beliefs their thoughts give rise to. Furthermore, yoga and meditation affect the emotions and one’s resulting behavior in a positive way by reducing the stress caused by an individual’s environment.

Quantifying Thoughts, Beliefs, Feelings and Behaviors

This section has been mainly written by Prof. Katarzyna Wac.

When yoga and meditation are practiced as techniques of self-empowerment, as will be discussed in section “Yoga and Meditation as Techniques for Achieving Self-Empowered Behavior”, it can be beneficial for the practitioner to assess changes to their thoughts, beliefs, emotions and behaviors through reliable means. This section therefore discusses how each of these variables can be quantified leveraging recent developments in personal, miniaturized technology such as smartphones and wearables to evaluate and ultimately improve the effectiveness of one’s practice. The table (Table 12.2) presents methods of quantifying these concepts using various data sources that are categorized in the manner defined by Mayo et al. in the context of patient care [147]. In this case, the tools and methods are adapted for the use of any individual in or outside of care settings. The first data source that is considered is self-reported data that the individual provides on their own. This includes information on both internal, unobservable states and external, observable states that is collected via patient-reported outcome (PRO) surveys for a given recall period (e.g., the last month) and in shorter ecological momentary assessments (EMAs) [148]. The second data source includes data reported by other individuals, such as a friend, family member or caregiver, on the individual in question’s perceived internal and observable states. This information is collected in the form of observer-reported outcome (ObsRO) surveys and/or peer ecological momentary assessments (PeerMAs) [149], the content of which may differ from the PRO surveys and EMAs depending on what is being reported upon (e.g., internal, unobservable states or external, observable states). The third data source includes technology-reported outcomes (TechRO) datasets collected via wearable devices that record aspects of the individual’s psychophysiology and their movements and via smartphones that record information concerning the individual’s context and their interaction with their context.

At present, the measurement of thoughts, beliefs, emotions and behaviors using the tools mentioned in Table 12.2, especially the technology-reported datasets, is only a hypothetical proposal. Concrete experimentation is still needed to ensure the accuracy, timeliness and reproducibility of the assessments of these variables [36] and the overall quality of the data collected. That said, these methods of quantification indicate a possible set of tools practitioners of meditation, yoga and other behavioral techniques might use to measure the effectiveness of their practices on their behavior and the variables—namely thoughts, beliefs and emotions—that ultimately shape behavior.

Yoga and Meditation as Techniques for Achieving Self-Empowered Behavior

Based on the research presented in this chapter up to this point, this section assesses yoga and meditation as techniques of individual empowerment through which one might change one’s health behaviors to live a happier life. In particular, this section focuses on the use of yoga and meditation techniques for stress management as a means of enacting behavioral change. Self-empowered changing of one’s health behaviors also implies an attempt to change one’s perspective towards health and illness. Such a change might involve adopting the view held by Antonovsky, who stated, “We are coming to understand health not as the absence of disease, but rather as the process by which individuals maintain their sense of coherence (i.e., sense that life is comprehensible, manageable, and meaningful) and ability to function in the face of changes in themselves and their relationships with their environment.” [150] A similar definition of health that one might adopt is “the ability to adapt and self-manage in the face of social, physical, and emotional challenges.” [151]

Yoga and meditation can improve one’s ability to generate thoughts that are capable of leading to positive emotions. Although cognitive methods by themselves can contribute to stress management [152], individuals can achieve better results when they integrate emotions into their methods. Recent studies indicate, for instance, that individuals adapt their behaviors more easily when they integrate emotions into behavioral change techniques [153]. One reason for this is that positive feelings towards a new situation can facilitate physiological and psychological acceptance of a change and of the new situation that results. Overall, it has been shown that when emotions are a focal point of behavioral change practices, individuals are more likely to successfully change their behavior and better able to improve their overall QoL. When practiced regularly, yoga and meditation can help induce unconscious shifts towards stress-reducing behavior and facilitate synchronization (coherence states) of a body’s heart rate and brainwaves.

Yoga and meditation can train one to develop an ability to change perspectives by being aware of one’s personal beliefs, which allows individuals to make choices regarding how they progress towards change. When individuals are able to change perspectives and show competence in empathy, they are ultimately more likely to change their behavior. For example, it has been demonstrated that an individual who wants to start doing more exercise to improve their QoL, better understands their negative emotions during moments when they are not exercising.

Yoga and meditation can empower individuals to change their perspective towards situations that are considered stressful. Some studies have demonstrated that one’s attitude towards stress plays a crucial role in the effort to reduce stress. Those who consider stress as something positive are more likely to manage it successfully than those who view it negatively.

Self-observation with meditation and yoga helps to raise awareness and activate unconscious processes; raised awareness is a result of logging emotional states [154]. Meanwhile, developing an emotion-focused understanding of stress allows one to better understand what is happening when one is dealing with undesired behaviors. Yoga and meditation increase awareness and understanding at critical behavioral moments. Meditation in particular also helps individuals to enter a state in which they are less focused on thoughts so that they can approach their emotions as an observer.

Individuals who wish to empower themselves may utilize technology for the self-assessment of their states and behaviors. As discussed in the previous section, miniaturized devices such as smartphones and wearables can be used to gather relevant quantitative data. The result of using these tools is what is called, in the study of technology, the quantified self [155], a term that equally describes the practitioner of yoga and meditation. There exists a myriad of personal digital devices [156] that can automatically gather information regarding physiological processes and hard-to-observe behaviors [156]. The use of these devices and the data they provide may motivate individuals to better understand the way certain thoughts, beliefs or feelings lead to specific behaviors. Researchers have found that individuals find it easier to internalize such knowledge when using technology and, consequently, are able to realize behavioral changes almost instantly [154]. In general, the idea that technology can enable the assessment of individual behaviors and health and produce improvements in life quality has been expressed before [157]. The next step in the process is to leverage these technologies to potentially focus on the assessment and improvement of the individual’s internal states—particularly their thoughts, beliefs and emotions.

Concluding Remarks

In this chapter, we have examined the role of personal beliefs, together with thoughts and emotions, in the development of behavioral habits. Considering stress as a reaction that is influenced by behavior, we discussed yoga and meditation practices as possible interventions to alter personal beliefs and influence behaviors and thereby reduce stress, leading ultimately to an improvement in QoL. In addition, we suggested the use of technological devices and other tools for quantifying thoughts, beliefs, emotions and behaviors as a means of further empowering behavioral change.

Many benefits of yoga and meditation have been uncovered in recent research, including their effect on stress reduction. It has been specifically shown that managing stress and adapting one’s behavior to live a more meaningful and fulfilled, healthier and happier life, depends very much on each individual’s thoughts, their personal beliefs and related emotions. Yoga and meditation, as techniques in which individuals seek to understand their perceptions and reactions towards stress and the outer world, are promising, learnable skills that can lead towards self-empowered behavioral change. Once the body has learned these skills, it reacts (i.e., thinks, believes, feels and behaves) unconsciously and without effort, even when the individual is not consciously paying attention. Studies have shown that, in such cases, behavioral change can then occur unconsciously.

Scientific research is now beginning to map the bioenergetic communication systems between the “inside” and “outside” of the body (including physiological functions, cognitive processes, emotions and behavior) that influence one’s health, happiness and QoL in the long term [158]. More research is expected to be carried out in the future concerning this important, interesting and impactful topic.

Change history

06 July 2022

Chapter 18: The original version of the book was inadvertently published with chapter 18 author’s family name captured as Chapuis. The author’s family name has now been corrected as Mercuri Chapuis.

Notes

- 1.

To learn more:

“There are four factors which Tones (1993) considers central to the concept of empowered action for the individual: (1) The environmental circumstances which may either facilitate the exercise of control or, conversely, present a barrier to free action. (2) The extent to which individuals actually possess competencies and skills which enable them to control some aspects of their lives, and perhaps overcome environmental barriers. (3) The extent to which individuals believe themselves to be in control. (4) Various emotional states or traits which typically accompany different beliefs about control—such as feelings of helplessness and depression, or feelings of self-worth.” p. 1274.

- 2.

Emotional valence (Definition).

“The concept of emotional valence, or simply valence, has been used among emotion researchers to refer to the positive and negative character of emotion or some of its aspects, including elicitors (events, objects), subjective experiences (feeling, affect) and expressive behaviors (facial, bodily, verbal). The valence of feelings has been argued to be a pivotal criterion for demarcating emotion and a core dimension of the subjective experience of moods and emotions.”

- 3.

Recent studies found out that individuals can influence and measure these impacts on emotions, for example psychophysiological functions like the heart rate. According to the HeartMath-Institute, “These positive emotion-focused techniques help individuals learn to self-generate and sustain a beneficial functional mode known as psychophysiological coherence, characterized by increased emotional stability and by increased synchronization and harmony in the functioning of physiological systems.” [43]. This tool helps restructuring emotions, and takes usually 5–15 min.

For in-depth descriptions of these techniques, see [52, 53].

- 4.

- 5.

The Spirituality Index of Well-being (SIWB) states that there is currently no instrument that can measure spirituality in its complexity, but it can deliver “health-related quality of life measures” in a qualitative form. The Spirituality Scale (SS) is a holistic approach measuring beliefs, intuitions, life choices and rituals. It identifies mainly three factors of spirituality: Self-Discovery, Relationships and Eco-Awareness. The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale (DSES) addresses spiritual experiences like awe, joy and a sense of deep inner peace. With this scale, emotions, cognition and behavior may be identified. According to the DSES, daily spiritual experience is related to improved Quality of Life and positive psychosocial status. As stated in the SIWB study, “Life scheme is similar to the construct of sense of coherence, which was described by Antonovsky as a positive, pervasive way of viewing the world, and one’s life in it, lending elements of comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness.”

- 6.

For example: “I accept others even if they do things I think are wrong” (Spirituality Scale (SS))

- 7.

Fifty-nine undergraduate students (25 males) participated in this experiment for course credit. The mean age of the sample was 21.7 (SD 2.0; range 18–25) years. Individuals were allocated to positive (n 20), negative (n 20), and neutral (n 19) mood induction conditions using a counterbalanced design.

From the study: [96].

- 8.

- 9.

Coherence is defined as the “synchronization or entrainment between multiple waveforms. A constructive waveform produced by two or more waves that are phase- or frequency-locked”.

Resource: https://www.heartmath.org/research/science-of-the-heart/coherence/

- 10.

- 11.

https://centerhealthyminds.org/science/overview (Accessed 02.06.2020)

- 12.

Concentrative meditation is the term sometimes used for a type of meditation in which the mind is focused entirely on one thought, object, sound or entity. The intention is to maintain the single-pointed concentration for the duration of the meditation. For an object of concentration, the yogi may use a sound or mantra, their breath or a physical object such as an icon or candle. https://www.yogapedia.com/definition/10427/concentrative-meditation

References

Whoqol Group. The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(10):1403–9.

Longo Y, Coyne I, Joseph S. The scales of general well-being (SGWB). Person Individual Diff. 2017;109:148–59.

Moreira-Almeida A, Koenig HG. Retaining the meaning of the words religiousness and spirituality: a commentary on the WHOQOL SRPB group’s “A cross-cultural study of spirituality, religion, and personal beliefs as components of quality of life”(62: 6, 2005, 1486–1497). Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(4):843–5.

Koenig HG, McCullough M, Larson DB. Handbook of religion and health: a century of research reviewed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001.

Krueger J. Personal beliefs and cultural stereotypes about racial characteristics. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1996;71(3):536–48.

Peterson M, Webb D. Religion and spirituality in quality of life studies. Appl Res Qual Life. 2006(1):107–16.

Kale SH. Spirituality, religion, and globalization. J Macromark. 2004;24(2):92–107.

Mackintosh N. Self-empowerment in health promotion: a realistic target? Br J Nursing. 1995;4(21):1273–8.

Heimlich JE, Ardoin NM. Understanding behavior to understand behavior change: a literature review. Environ Educ Res. 2008;14(3):215–37.

Oishi S, Diener E, Lucas RE. The optimum level of well-being: can people be too happy?. In: The science of well-being. Dordrecht: Springer; 2009. p. 175–200, 347.

Atkinson S. Beyond components of wellbeing: the effects of relational and situated assemblage. Topoi. 2013;32(2):137–44.

Carlisle S, Henderson G, Hanlon PW. ‘Wellbeing’: a collateral casualty of modernity? Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(10):1556–60.

Lyubomirsky S. Why are some people happier than others? The role of cognitive and motivational processes in well-being. Am Psychol. 2001;56(3):239.

Freedman JL. Happy people: what happiness is, who has it, and why. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; 1978.

Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE, Smith HL. Subjective well-being: three decades of progress. Psychol Bull. 1999;125(2):276–302.

Ryff CD, Dienberg G, Love E, Marilyn J, Singer B. Resilience in adulthood and later life. Defining features and dynamic processes. In: Lomranz J, editor. Handbook of aging and mental health. The Springer series in adult development and aging. Boston, MA: Springer; 1998.

Taylor SE, Brown JD. Illusion and well-being: a social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychol Bull. 1988;103(2):193–210.

Eysenck MW. Basil Blackwell (1990): The Blackwell dictionary of cognitive psychology, ed.

Eysenck MW. Basil Blackwell (1990): The Blackwell dictionary of cognitive psychology, ed., p. 240.

Sumner LW. Welfare, happiness, and ethics. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996.

Ahmed S. Killing joy: feminism and the history of happiness. Signs: J Women Cult Soc. 2010;35(3):571–94.

Ehrenreich B. Smile or die: how positive thinking fooled America and the world. Granta books; 2010.

Samman E. Psychological and subjective wellbeing: a proposal for internationally comparable indicators. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1995; 2007. OPHI Working Paper Series.

Ryff CD, Keyes CL. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69:719–27.

Ryff CD, Lee YH, Essex MJ, Schmutte PS. My children and me: midlife evaluations of grown children and of self. Psychol Aging. 1994;9:195–205.

Ryff CD, Dienberg Love G, Urry HL, Muller D, Rosenkranz MA, Friedman EM, Davidson RJ, Singer B. Psychological well-being and ill-being: do they have distinct or mirrored biological correlates? Psychother Psychosom. 2006;75:85–95.

Wrosch C, Scheier MF, Miller GE, Schulz R, Carver CS. Adaptive self-regulation of unattainable goals: goal disengagement, goal reengagement, and subjective well-being. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2003;29:1494–508.

Levi L, editor. Stress and distress in response to psychosocial stimuli: laboratory and real-life studies on sympatho-adrenomedullary and related reactions. Oxford: Pergamon Press; 2016. p. 11.

Levi L, editor. Stress and distress in response to psychosocial stimuli: laboratory and real-life studies on sympatho-adrenomedullary and related reactions. Oxford: Pergamon Press; 2016. p. 13.

Levi L, editor. Stress and distress in response to psychosocial stimuli: laboratory and real-life studies on sympatho-adrenomedullary and related reactions. Oxford: Pergamon Press; 2016. p. 14.

Robinson MD, Johnson JT. Is it emotion or is it stress? Gender stereotypes and the perception of subjective experience. Sex Roles. 1997;36(3–4):235–58.

Mulligan K, Scherer KR. Toward a working definition of emotion. Emotion Rev. 2012;4(4):345–57.

Wang M, Saudino KJ. Emotion regulation and stress. J Adult Dev. 2011;18(2):95–103.

McCraty R, Atkinson M, Tomasino D, Bradley RT. Heart–brain interactions, psychophysiological coherence, and the emergence of system-wide order. HeartMath Research Center, Institute of HeartMath, Publication No. 06-022. Boulder Creek; 2006. p. 3.

McCraty R, Atkinson M, Tomasino D, Bradley RT. Heart–brain interactions, psychophysiological coherence, and the emergence of system-wide order. HeartMath Research Center, Institute of HeartMath, Publication No. 06-022. Boulder Creek; 2006. p. 25–6.

Kreibig SD. Autonomic nervous system activity in emotion: a review. Biol Psychol. 2010;84(3):394–421.

Colombetti G. Appraising valence. J Consciousness Stud. 2005;12(8–9):103–26.

McCraty R, Atkinson M, Tomasino D, Bradley RT. Heart–brain interactions, psychophysiological coherence, and the emergence of system-wide order. HeartMath Research Center, Institute of HeartMath, Publication No. 06-022. Boulder Creek; 2006. p. 5.

McCraty R, Atkinson M, Tomasino D, Bradley RT. Heart–brain interactions, psychophysiological coherence, and the emergence of system-wide order. HeartMath Research Center, Institute of HeartMath, Publication No. 06-022. Boulder Creek; 2006. p. 10.

Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1238–45.

Naghavi M, Abajobir AA, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, Ahmadi A, et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. The Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1151–210.

Hollis V, Konrad A, Whittaker S. Change of heart: emotion tracking to promote behavior change. In: Proceedings of the 33rd annual ACM conference on human factors in computing systems; 2015. p. 2643–52.

McCraty R, Atkinson M, Tomasino D, Bradley RT. Heart–brain interactions, psychophysiological coherence, and the emergence of system-wide order. HeartMath Research Center, Institute of HeartMath, Publication No. 06-022. Boulder Creek; 2006. p. 2.

McCraty R, Atkinson M, Tomasino D, Bradley RT. Heart–brain interactions, psychophysiological coherence, and the emergence of system-wide order. HeartMath Research Center, Institute of HeartMath, Publication No. 06-022. Boulder Creek; 2006. p. 6.

McCraty R, Atkinson M, Tomasino D, Bradley RT. Heart–brain interactions, psychophysiological coherence, and the emergence of system-wide order. HeartMath Research Center, Institute of HeartMath, Publication No. 06-022. Boulder Creek; 2006. p. 7.

Rea S. Tending the heart fire: living in flow with the pulse of life. Boulder: Sounds True; 2014. p. 61.

Rea S. Tending the heart fire: living in flow with the pulse of life. Boulder: Sounds True; 2014. p. 58.

McCraty R. Science of the heart, Volume 2: Exploring the role of the heart in human performance: Rollin McCraty Ph. D., Sandy Royall. Boulder Creek: HeartMath Institute; 2015. p. 43.

McCraty R. Science of the heart, Volume 2: Exploring the role of the heart in human performance: Rollin McCraty Ph. D., Sandy Royall. Boulder Creek: HeartMath Institute; 2015. p. 42.

McCraty R, Atkinson M, Tomasino D, Bradley RT. Heart–brain interactions, psychophysiological coherence, and the emergence of system-wide order. HeartMath Research Center, Institute of HeartMath, Publication No. 06-022. Boulder Creek; 2006. p. 47.

McCraty R, Atkinson M, Tomasino D, Bradley RT. Heart–brain interactions, psychophysiological coherence, and the emergence of system-wide order. HeartMath Research Center, Institute of HeartMath, Publication No. 06-022. Boulder Creek; 2006. p. 31.

Childre D, Martin H, Beech D. The HeartMath solution: The Institute of HeartMath’s Revolutionary Program for Engaging the Power of the Heart’s Intelligence. New York: HarperOne; 2000.

Childre D, Rozman D. Transforming stress: the HeartMath solution for relieving worry, fatigue, and tension. Oakland: New Harbinger Publications; 2005.

Levitis D, William ZL, Glenn F. Behavioral biologists do not agree on what constitutes behavior. Anim Behav. 2009;78:103–10.

Romer P, M. Thinking and feeling. Am Econ Rev. 2000;90(2):439–43.

Gigerenzer G, Hertwig R, et Pachur T, editors. Heuristics: the foundations of adaptive behavior. Oxford University Press; 2011.

Tiller WA. What are subtle energies? In: Journal of Scientific Exploration, 1993; 7(3): Altern Complement Med. 2004;10(2):307–14. 293–304.

Geraerts E, Bernstein DM, Merckelbach H, Linders C, Raymaekers L, Loftus EF. Lasting false beliefs and their behavioral consequences. Psychol Sci. 2008;19:749–53.

Barth F, Chiu C, Rodseth L, Robb J, Rumsey A, Simpson B, Barth F, et al. An anthropology of knowledge. Curr Anthropol. 2002;43(1):1–18.

Baumeister RF, Masicampo EJ, Vohs KD. Do conscious thoughts cause behavior? Annu Rev Psychol. 2011;62:331–61.

Gigerenzer G, Brighton H. Can hunches be rational. JL Econ. & Pol’y. 2007;4:155.

Cohen DA, Scribner RA, Farley TA. A structural model of health behavior: a pragmatic approach to explain and influence health behaviors at the population level. Prevent Med. 2000;30(2):146–54.

Mehl M. Why researchers should think “real-time”: a cognitive rationale. In: Handbook of research methods for studying daily life. New York: Guilford Press; 2013.

Berger J. Invisible influence: the hidden forces that shape behavior. London: Simon & Schuster; 2016. p. 2.

Bargh JA. Reply to the commentaries; 1997. See Wyer 1997, 10:231–46, p. 243.

Dhami MK, Hertwig R, Hoffrage U. The role of representative design in an ecological approach to cognition. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(6):959–88.

Barth F, Chiu C, Rodseth L, Robb J, Rumsey A, Simpson B, Barth F, et al. An anthropology of knowledge. Curr Anthropol. 2002;43(1):2.

Barth F, Chiu C, Rodseth L, Robb J, Rumsey A, Simpson B, Barth F, et al. An anthropology of knowledge. Curr Anthropol. 2002;43(1):10.

Anderson CA. Imagination and expectation: the effect of imagining behavioral scripts on personal influences. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1983;45:293–305.

Barth F, Chiu C, Rodseth L, Robb J, Rumsey A, Simpson B, Barth F, et al. An anthropology of knowledge. Curr Anthropol. 2002;43(1):1.

Armitage CJ, Conner M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behavior: a meta-analytic review. Br J Soc Psychol. 2001;40(4):471–99.

Ajzen I, Fishbein M. The influence of attitudes on behaviour. In: Albarracin D, Johnson BT, Zanna MP, editors. The handbook of attitudes. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2005.

Armor DA, Taylor SE. The effects of mindset on behavior: self-regulation in deliberative and implemental frames of mind. Person Soc Psychol Bull. 2003;29(1):92.

Taylor SE, Lerner JS, Sherman DK, Sage RM, McDowell NK. Are self-enhancing cognitions associated with healthy or unhealthy biological profiles? J Personal Soc Psychol. 2003;85(4):605–15.

Galinsky AD, Maddux WW, Gilin D, White JB. Why it pays to get inside the head of your opponent: the differential effects of perspective taking and empathy in negotiations. Psychol Sci. 2008;19:378–84.

Galinsky AD, Wang CS, KuG. Perspective-takers behave more stereotypically. J Personal Soc Psychol. 2008b;95:404–19.

Ackerman JM, Goldstein NJ, Shapiro JR, Bargh JA. You wear me out: the vicarious depletion of selfcontrol. Psychol Sci. 2009;20:326–32.

Bambling M. Mind, body and heart: psychotherapy and the relationship between mental and physical health. Psychother Aust. 2006;12(2)

Gustafson A, Ballew MT, Goldberg MH, Cutler MJ, Rosenthal SA, Leiserowitz A. Personal stories can shift climate change beliefs and risk perceptions: the mediating role of emotion. Commun Rep. 2020;33(3):121–35.

Ferrini R, Edelstein S, Barrettconnor E. The association between health beliefs and health behavior change in older adults. Prevent Med. 1994;23(1):1–5.

Valente TW, Pumpuang P. Identifying opinion leaders to promote behavior change. Health Educ Behav. 2007;34(6):881–96.

Usher EL. Personal capability beliefs. Handb Educ Psychol. 2015;3:146–59.

Steeves JA, Liu B, Willis G, Lee R, Smith AW. Physicians’ personal beliefs about weight-related care and their associations with care delivery: the US National Survey of energy balance related care among primary care physicians. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2015;9(3):243–55.

Frank De Jerome D, Frank JB. Persuasion and healing: a comparative study of psychotherapy. JHU Press; 1993.

Frank KA. The “ins and outs” of enactment: a relational bridge for psychotherapy integration. J Psychother Integr. 2002;12(3):267–86.

Werth JL Jr, Blevins D, Toussaint KL, Durham MR. The influence of cultural diversity on end-of-life care and decisions. Am Behav Sci. 2002;46(2):204–19.

O’Connell KA, Skevington SM. Spiritual, religious, and personal beliefs are important and distinctive to assessing quality of life in health: a comparison of theoretical models. WHO Centre for the Study of Quality of Life, Department of Psychology, University of Bath. Br J Health Psychol. 2009;00:1–21.

Unsworth S, Palicki SK, Lustig J. The impact of mindful meditation in nature on self-nature interconnectedness. Mindfulness. 2016;7(5):1052–60.

Barrett M, Uí Dhuibhir P, Njoroge C, Wickham S, Buchanan P, Aktas A, Walsh D. Diet and nutrition information on nine national cancer organisation websites: a critical review. Eur J Cancer Care. 2020;29(5):e13280.

Alvesson M, Willmott H. Identity regulation as organizational control: producing the appropriate individual. J Manage Stud. 2002;39(5):619–44.

Ananth S. Developing healing beliefs. 2009;5(6):354–5.

Wirth D. The significance of belief and expectancy within the spiritual healing encounter. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(2):249–60.

Schmidt S. Mindfulness and healing intention: concepts, practice, and research evaluation. J Complement Altern Med. 2004;10:S7–S14.

Montaño DE, Kasprzyk D. Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. In: Glanz K, Barbara K, Rimer K, editors. Health behavior: theory, research, and practice. 4th ed. Wiley; 2008.

Hagger MS, Cameron LD, Hamilton K, Hankonen N, Lintunen T, editors. The handbook of behavior change. Cambridge University Press; 2020.

Smallwood J, Fitzgerald A, Miles LK, Phillips LH. Shifting moods, wandering minds: negative moods lead the mind to wander. Emotion. 2009;9(2):271–6.

Bennett MR, Hacker PMS. History of cognitive neuroscience. New York: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. p. 166.

Zeelenberg M, Nelissen RM, Breugelmans SM, Pieters R. On emotion specificity in decision making: why feeling is for doing. Judgment Decision Making. 2008;3(1):18.

Avey JB, Wernsing TS, Luthans F. Can positive employees help positive organizational change? Impact of psychological capital and emotions on relevant attitudes and behaviors. J Appl Behav Sci. 2008;44(1):48.

Belschak FD, Hartog D, Deanne N. Consequences of positive and negative feedback: the impact on emotions and extra-role behaviors. Appl Psychol. 2009;58(2):274.

Adhia, Hasmukh, H. R. Nagendra, and B. Mahadevan. “Impact of adoption of yoga way of life on the emotional intelligence of managers.” IIMB Management Review. 2010;22(1-2):32–41.

Park, Crystal L. et al. “How does yoga reduce stress? A clinical trial testing psychological mechanisms.” Stress and Health. 2021;37(1):116–126.

Verma, Sudhanshu, Kamakhya Kumar. “Evidence-based comparative study of group and individual consciousness on life satisfaction among adults.” Yoga Mimamsa. 2020;52(1):34.

Boeger, Gabriella H. YOGA THROUGH A SYSTEMIC LENS: THE IMPACT OF YOGA PRACTICE ON SELF-COMPASSION, COUPLE SATISFACTION, AND FAMILY FUNCTIONING. Diss. Purdue University Graduate School, 2020.

Kupershmidt S, Barnable T. Definition of a yoga breathing (pranayama) protocol that improves lung function. Holistic Nursing Pract. 2019;33(4):197.

De Michelis E. A history of modern yoga: Patanjali and western esotericism. London: A & C Black; 2005.

Ignatow G. Culture and embodied cognition: moral discourses in internet support groups for overeaters. Social Forces. 2009;88(2) (The University of North Carolina Press, 643–70. p. 415).

Ignatow G. Culture and embodied cognition: moral discourses in internet support groups for overeaters. Social Forces. 2009;88(2) (The University of North Carolina Press, 643–70)

Csordas TJ. Embodiment and experience. Cambridge University Press; 1994.

Scheper-Hughes N, Lock MM. The mindful body: a prolegomenon to future work in medical anthropology. Med Anthropol Q. 1987;1(1):6–41.

Swami Rama R, Ballentine SA. Yoga and psychotherapy: the evolution of consciousness. Honesdale, PA: Himalayan International Institute; 1976.

Menezes CB, Dalpiaz NR, Kiesow LG, Sperb W, Hertzberg J, Oliveira AA. Yoga and emotion regulation: a review of primary psychological outcomes and their physiological correlates. Psychol Neurosci. 2015;8(1):82.

Zuo XL, Li Q, Gao F, Yang L, Meng FJ. Effects of yoga on negative emotions in patients with breast cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Nurs Sci. 2016;3(3):299–306.

Francis AL, Beemer RC. How does yoga reduce stress? Embodied cognition and emotion highlight the influence of the musculoskeletal system. Complement Therap Med. 2019;43:170–5.

Froeliger B, Garland EL, Modlin LA, McClernon FJ. Neurocognitive correlates of the effects of yoga meditation practice on emotion and cognition: a pilot study. Front Integrative Neurosci. 2012;6:48.

Khedikar SG, Erande MP, Shukla Deepnarayan V. Critical comparison of yogic nadi with nervous system. Joinsysmed. 2016;4(2):108–13.

Institute of HeartMath: https://www.heartmath.org/research/science-of-the-heart/heart-brain-communication/. Accessed 29 May 2020.

Salmon P, Lush E, Jablonski M, Sephton SE. Yoga and mindfulness: clinical aspects of an ancient mind/body practice. Cogn Behav Pract. 2009;16:59–72.

Streeter CC, Gerbarg PL, Saper RB, Ciraulo DA, Brown RP. Effects of yoga on the autonomic nervous system, gamma-aminobutyric-acid, and allostasis in epilepsy, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Med Hypotheses. 2012;78:571–9.

McCraty R, Atkinson M, Tomasino D, Bradley RT. Heart–brain interactions, psychophysiological coherence, and the emergence of system-wide order. HeartMath Research Center, Institute of HeartMath, Publication No. 06-022. Boulder Creek; 2006. p. 23.

Cahn BR, Polich J. Meditation states and traits: EEG, ERP, and neuroimaging studies. Psychol Bull. 2006;132(2):180–211.

McCraty R, Atkinson M, Tomasino D, Bradley RT. Heart–brain interactions, psychophysiological coherence, and the emergence of system-wide order. HeartMath Research Center, Institute of HeartMath, Publication No. 06-022. Boulder Creek; 2006. p. 11.

Arias AJ, Steinberg K, Banga A, Trestman RL. Systematic review of the efficacy of meditation techniques as treatments for medical illness. J Alternat Complement Med. 2006;12(8):817–32.

Ospina MB, Bond K, Karkhaneh M, Tjosvold L, Vandermeer B, Liang Y, Bialy L, Hooton N, Buscemi N, Dryden DM, Klassen TP, editors. Meditation practices for health: state of the research. AHRQ Publications; 2007.

Hayes JA, Davis DM. What are the benefits of mindfulness? A practice review of psychotherapy-related research. Psychother Am Psychol Assoc. 2011;48(2):198–208.

Farb N, Segal ZV, Mayberg H, Bean J. Attending to the present: mindfulness meditation reveals distinct neural modes of self-reference. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2008;2(4):313–22.

Corcoran KM., Farb N, Anderson A, Segal ZV. Mindfulness and emotion regulation: outcomes and possible mediating mechanisms; 2010.

Siegel DJ. Mindfulness training and neural integration: differentiation of distinct streams of awareness and the cultivation of well-being. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2007;2(4):259–63.

Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness meditation. Mind-Body-Medicine, earthandspiritcenter.org. 1995.

Eppley KR, Abrams AI, Shear J. Differential effects of relaxation techniques on trait anxiety: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol. 1989;45:957–74.

Barnes VA, Treiber FA, Davis H. Impact of transcendental meditation on cardiovascular function at rest and during acute stress in adolescents with high normal blood pressure. J Psychosomatic Res. 2001;51:597–605.

Orme-Johnson DWK, Lonsdorf N. Meditation in the treatment of chronic pain and insomnia. In: National Institutes of Health Technology Assessment Conference on Integration of Behavioral and Relaxation Approaches into the Treatment of Chronic Pain and Insomnia. Bethesda Maryland: National Institutes of Health; 1995.

Ray US, Sinha B, Tomer OS, Pathak A, et al. Aerobic capacity & perceived exertion after practice of Hatha yogic exercises. Indian J Med Res New Delhi. 2001;114:215–21.

Barrett B, Hayney MS, Muller D, Rakel D, Ward A, Obasi CN, Brown R, Zhang Z, Zgierska A, Gern J, West R, Ewers T, Barlow S, Gassman M, Coe CL. Meditation or exercise for preventing acute respiratory infection: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(4):337–46.

Siegle GJ, Steinhauer SR, Thase ME, Stenger V, Andrew; Carter, Cameron S. Can’t shake that feeling: event-related FMRI assessment of sustained amygdala activity in response to emotional information in depressed individuals. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51(9):693–707.

Fredrickson BL. Cultivating positive emotions to optimize health and well-being. Prevent Treatment. 2000;3(1):1a.

Fredrickson BL, Cohn MA, Coffey KA, Pek J, Finkel SM. Open hearts build lives: positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. J Personal Soc Psychol. 2008;95(5):1045.

Pribram KH, Melges FT. Psychophysiological basis of emotion. In: Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW, editors. Handbook of clinical neurology. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company; 1969. p. 316–41.

Bradley RT, Pribram KH. Communication and stability in social collectives. J Soc Evolut Syst. 1998;21(1):29–80.

Pribram KH, Bradley RT. The brain, the me and the I. In: Ferrari M, Sternberg R, editors. Self-awareness: its nature and development. New York: The Guilford Press; 1998. p. 273–307.

McCraty R, Atkinson M, Tomasino D, Bradley RT. Heart–brain interactions, psychophysiological coherence, and the emergence of system-wide order. HeartMath Research Center, Institute of HeartMath, Publication No. 06-022. Boulder Creek; 2006. p. 25.

McCraty R, Atkinson M, Tomasino D, Bradley RT. Heart–brain interactions, psychophysiological coherence, and the emergence of system-wide order. HeartMath Research Center, Institute of HeartMath, Publication No. 06-022. Boulder Creek; 2006. p. 27.

NEFF, Kristin D. The role of self-compassion in development: a healthier way to relate to oneself. Hum Dev. 2009;52(4):211–4.

Armor DA, Taylor SE. Situated optimism: specific outcome expectancies and self-regulation. In: Zanna Mark P, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology, vol. 30. Academic Press; 1998. p. 309–79.

Gardner B, Lally P. Does intrinsic motivation strengthen physical activity habit? Modeling relationships between self-determination, past behavior, and habit strength. J Behav Med. 2013;36:488–97.

Dahl J, Lutz A, Davidson RJ. Reconstructing and deconstructing the self: cognitive mechanisms in meditation practice. Trends Cogn Sci. 2015;19(9):515–23.