Abstract

This paper analyses the evolution of public support for the euro from 1990 to 2011, using a popularity function approach, focusing on the most recent period of the financial and sovereign debt crisis. Exploring a huge database of close to half a million observations, covering the 12 original euro area member countries, we find that the ongoing crisis has only marginally reduced citizens’ support for the euro – at least so far. This result is in stark contrast to the sharp fall in public trust in the European Central Bank. We conclude that the crisis has hardly dented popular support for the euro while the central bank supplying the single currency has lost ground in public trust. Thus, the euro appears to have established a credibility of its own – separate from the institutional framework behind the currency.

Originally published in: Felix Roth, Lars Jonung and Felicitas Nowak-Lehmann D. The Enduring Popularity of the Euro throughout the Crisis. Centre for European Policy Studies. Commissioned by Stiftung Mercator, CEPS Working Document No. 358, 2011.

Felix Roth gratefully acknowledges the generous support from Stiftung Mercator in financing the research project, Has the crisis in the eurozone undermined citizens. support for EMU and the euro?–, which led to this study. He would also like thank Raf van Gestel for excellent research assistance.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Ever since the plans for a European Monetary Union and a single European currency were announced, social scientists have explored the determinants of public attitudes towards the new currency. This study falls into this expanding area by analysing public support for the euro over a 21-year period from 1990 to 2011 for 12 euro member states (Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain – the EA-12), with a focus on the 2002–11 period in the econometric analysis. We compare the pre-crisis period 2002–08 with the crisis period 2008–11. In this way, we are able to evaluate the impact of the financial crisis (autumn 2008–spring 2011) on citizens’ support for the euro. Our study is inspired by the observation that citizens’ trust in the ECB has fallen sharply during the financial and sovereign debt crisis (Gros & Roth, 2009, 2010; Roth, 2009; Roth et al., 2011b). This raises the question: Has the euro, the currency supplied by the ECB, also suffered a loss in public support comparable to the fall in trust in the ECB?

Our study is based on the literature on popularity functions (Nannestad & Paldam, 1994). In this way we examine the determinants of public support behind the euro, focusing on inflation, unemployment, and growth of GDP per capita as our explanatory variables. We analyse the determinants of support for the euro on an aggregate level by using a fixed effects Dynamic Feasible Generalized Least Squares (DFGLS) panel analysis starting in 2002, when the euro became the transaction currency used in everyday life.

A graphic and econometric analysis reveals that there is no empirical evidence for a significant erosion of citizens’ support (although we detect a small reduction) as a result of the ongoing financial and sovereign debt crisis, at least not so far. Euro support stays at a relatively high level even in times of crisis and seems not to be affected by the standard macroeconomic variables in the popularity approach. Citizens’ support for the euro is also manifested by the fact that for the two decades covered by our analysis, the euro has always been supported by a majority of citizens in the euro area. The suggestion that “the global economic crisis has sapped support for the euro” (Jones, 2009) has very weak empirical support – so far as least.

1 Measuring Public Support for the Single Currency

We construct our measure of public support for the euro from data on responses to Eurobarometer (EB) surveys carried out bi-annually since the fall of 1990 (Standard EB 34) until the spring of 2011 (Standard EB 75). Eurobarometer surveys normally cover about 1,000 respondents per member country in the EU. The interviews are conducted face to face in the home of the respondents. For each Standard EB survey, new and independent samples are drawn. The basic sampling design in all EU member states is multi-stage and random (probability), thereby guaranteeing the polling of a representative sample of the population.

To measure public support for the euro we asked survey respondents their opinion on several proposals: “Please tell me for each proposal, whether you are for it or against it”. One proposal then states: “A European Monetary Union with one single currency, the Euro”.Footnote 1 The respondent can then choose from the following answers: “For”, “Against” or “Don’t Know”. The use of this survey question underlies the literature on public attitudes towards the single currency (see e.g. Kaltenthaler & Anderson, 2001; Banducci et al., 2003, 2009; Kaelberer, 2007; Jonung, 2011). As the response rate of the “Don’t Know” answer fluctuates over the entire sample (ranging from 0 to 34 and a mean of 8 with a standard deviation of 3.5), we focus on the average percentage of net support measured as the number of “For” responses minus “Against” responses to the above question on the country level in our analysis. Figure 9.1 shows this measure of citizens’ net support for the single currency in the EA-12 country sample from 1990 to 2011.

Average net support for the single currency in the EA-12 countries, 1990–2011

Notes: The measure for net support is based upon approximately 497,800 individual responses. As the figure depicts net support, all values above 0 indicate that a majority of the respondents support the single currency. For the aggregation of the 12 euro area countries, population weights were applied.

Sources: Aggregated data from 1990 to 2011 include observations from EB34 to EB75. EB38–71 was purchased from TNS-Emnid. Data from EB34–37 were drawn from Gesis (2005). Data for EB72–75 from autumn 2009 to spring 2011 were drawn from Eurobarometer (2009, 2010a, b and 2011). The aggregated trend from 1990 to 1994 is based on 10 EA countries, that is EA-12 excluding Austria and Finland. Starting from spring 1995, Austria and Finland are included in the sample.

We identify four distinct phases in the history of the euro during the period 1990–2011 in Fig. 9.1. The first period covers the 1990s up to the actual launch of the euro area on 1 January 1999, with irrevocably pegged exchange rates among the euro area members. In autumn 1990, net support levels started with an overwhelming majority of citizens supporting the euro (41.1%). From autumn 1990 until spring 1993, net support for the euro deteriorated. This deterioration may be explained by exchange rate developments (Banducci et al., 2003, pp. 693–694). From autumn 1992 until autumn 1997, net support levels hovered in a narrow range with an average value of 24%. Thus, before the introduction of the euro in 1999, a clear majority of citizens supported the single currency. Within the first period – from autumn 1997 until autumn 1998 during the run-up to the euro launch – there was a rapid increase in net support to 51%. During this phase, the euro was favourably received in the media across Europe (see e.g. Brettschneider et al., 2003).

The second period starts with the introduction of the euro as a bookkeeping entity in January 1999 and ends with the launch of the euro as a fully-fledged currency and its introduction physically into circulation in January 2002. Initially, net support deteriorated by 21% points from 51% to 30% until spring 2000 in this second phase. This deterioration is sometimes explained by the decline of the euro vis-à-vis the US dollar (Banducci et al., 2003; Banducci et al., 2009, p. 566; Hobolt & Leblond, 2009). We suggest that the decline may also be a backlash following its positive exposure in the media shortly before January 1999 (e.g. Brettschneider et al., 2003).

Our third period starts when the euro entered into circulation on the first of January 2002. Initially, net support increased by 12% points from 43% to up to 55%, similar to the pattern of 1997–98. From autumn 2003 onwards, net support remains stable at an average level of around 41% (with a standard deviation of 3%) until spring 2011. The stable trend and low standard deviation of 3% suggests that there is no structural break between the pre-crisis period, our third phase, and the financial and sovereign debt crisis period, our fourth phase. In the direct aftermath of the financial crisis, support for the euro actually increased from spring 2008 to autumn 2008 from 40% to 44%, followed by a decrease to 36% in the spring of 2010. In the midst of the sovereign debt crisis, support increased again to 41% in autumn 2010 and decreased to 38% in spring 2011.

Figure 9.1 demonstrates that starting from modest positive levels (24%) prior to its introduction, net support for the euro was stabilised at a significantly higher level (41%) after two decades. Most noteworthy, during the financial and sovereign debt crises in 2008–11, there is only a small decline in popular support for the euro.

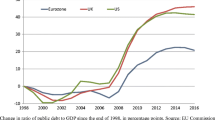

How do these results compare to the evolution of public trust in the ECB? As depicted in Table 9.1 and Fig. 9.A1 (in the Appendix), public trust in the ECB dropped from 29% in spring 2008 to 2% in spring 2011, while support for the euro declined only from 40% to 38% during the same period. Similarly, but less dramatic, a loss of institutional trustFootnote 2 in the European Commission, the European Parliament and the European Union is also registered.

One possible explanation for the diverging results between popular support behind the euro and popular trust in the ECB may be that the two measures cover different concepts. Thus, they should be compared with caution. Recent empirical findings on falling public trust in the euro in Germany (Köcher, 2010) suggest that this argument might be plausible. The question now is what do the two measures actually reflect: “trust” in the euro or “support” for the euro?Footnote 3 It seems reasonable to interpret “trust” in the euro as “trust” in the purchasing power of this type of money (see Kaelberer, 2007, pp. 625–626), similar to “trust” in the stability of the Deutsche Mark. “Support” for the euro would then mean support for the idea of a single European currency while not necessarily meaning that the respondent expects the euro to deliver a stable purchasing power. The support for the euro would then indicate that respondents are willing to “transfer power from the nation state to European institutions” (Kaltenthaler & Anderson, 2001, p. 141) and that they support the idea of a single European currency. In addition, the question is not only directed towards the euro but also towards the European Monetary Union as the relevant question in the survey (EB56–72) asks: “Are you for or against a European Monetary Union with one single currency, the euro”. Thus, whereas the question about “trust” seems appropriate to capture the concept of institutional trust, such as trust in the ECB, the European Commission or the European Parliament, the Eurobarometer question concerning “support” for the euro and the EMU is most likely a better measure than “trust” to clearly distinguish the euro as being the single currency for Europe (including the transfer of monetary power to the ECB).

From the reasoning above, we interpret the decline in trust in the ECB to imply that European citizens blame the ECB for not preventing the economic, financial and political turmoil during the crisis and suspect that the crisis measures taken by the ECB and other European institutions have had an inflationary effect (see here Roth et al., 2011b). The almost constant popular support behind the euro during the crisis suggests that the respondents support the euro as their currency and that they do not blame the euro for the crisis.

To analyse the individual discrepancies behind the aggregated net support for the euro, Fig. 9.2 focuses on the three largest euro area economies; Germany, France and Italy. Figure 9.2 shows a common convergence in the support for the euro in all three countries, with a clear catch-up process in Germany from 1993 onwards. Whereas all three countries start off with values between 25% to 62% from 1993 onwards they differ largely on their level of net support, with Germany with −17%, France with 26% and Italy with 68%. These trends converge to levels of 31% to 42% in the aftermath of the euro’s introduction and remain relatively stable from 2006 onwards at levels of around 40%.Footnote 4 In spring 2011, German respondents display a net support of 31%, French citizens a net support of 42% and Italian citizens of 41%. These numbers are in sharp contrast to trust in the ECB, which reached levels of 8, −5 and 9, respectively in spring 2011 (Roth et al., 2011b). Most astonishingly, a clear majority of German respondents supported the euro in autumn 1990. The steady fall from 1990 to 1993 is explained in the literature by the rise in the German exchange rate (Banducci et al., 2003, p. 694). The corresponding data for other euro area countries and non-euro area countries are depicted in Figs. 9.A2, 9.A3, 9.A4 and 9.A5. The pattern for Greece is especially noteworthy. In contrast to a massive drop in Greece in trust in almost all national and European institutions (Roth et al., 2011a), the support for their own (European) currency has been increasing throughout the European debt crisis. Whereas net support for the euro was 2% in spring 2008, it rose during the sovereign debt crisis to 24% in spring 2011. In addition, Figs. 9.A4 and 9.A5 demonstrate that levels of euro support in the non-euro area countries are significantly lower than in euro area countries and that the sovereign debt crisis has significantly eroded support for the euro in the non-euro countries, in particular in the UK (with a record low in all EU-27 countries of −58% in autumn 2010), Sweden, Denmark and the Czech Republic.

Net support for the euro in France, Germany and Italy, 1990–2011

Notes: The aggregated data for Germany are calculated from approximately 75,000, observations and 37,000 observations for France and Italy, respectively. As the figure depicts net support, all values above 0 indicate that a majority of the respondents support the single currency.

Sources: Aggregated data from 1990 to 2011 include observations from EB34 to EB75. EB38–71 was purchased from TNS-Emnid. Data from EB34–37 were drawn from Gesis (2005). Data for EB72–75 from autumn 2009 to spring 2011 were drawn from Eurobarometer (2009, 2010a, 2010b, 2011).

2 Determinants of Euro Support

So far this contribution has summarised the evolution of popular support for the euro. Next, we try to identify the major economic determinants of support for the single currency. Here we adopt the approach embedded in the literature on popularity functions (Nannestad & Paldam, 1994). The popularity function is a key concept in public choice or political economy. The basic idea behind the popularity function is that the public/the voters hold the government in office responsible for the performance of the macro-economy and/or economic events in general. Usually the popularity of a government as revealed by public opinion polls is postulated as a function of a set of macroeconomic variables like inflation, unemployment, and growth of GDP per capita. The intuition is that inflation and unemployment are negatively related to the popularity of the government while GDP growth is positively related. In short, the government is rewarded/punished for the behaviour of the macro-economy.

There are obvious similarities between the popularity of a government and the popularity of a currency like the euro. The popularity of a government is influenced by its ability to manage the economy at large, in short by its economic governance. Likewise, we expect the governance of the euro – that is, the monetary governance of the ECB – to be a function of the outcome of monetary policy, first of all as it is reflected in the rate of inflation in the euro area as measured by official statistics. Much of the research on public support behind the euro and European political integration is focused on economic determinants – although political and historical factors also have an impact.Footnote 5

The empirical tests of popularity functions generally confirm the significance of macroeconomic variables, in particular the rate of unemployment and inflation. However, the lack of stability of econometric results is a problem in this field of work (see e.g. Kirchgässner, 2009, who shows for the case of Germany that the popularity function has disappeared in recent times). Endogeneity is also a serious concern in the econometric analysis.

When estimating popularity functions for the euro, we contribute to the empirical literature in two respects. First, we explicitly take feedback effects between support for the euro and the macroeconomic environment into account. Tackling this issue (endogeneity, in technical terms), we are able to produce unbiased estimates. To this end, we adopt the Dynamic Ordinary Least Squares approach (Saikkonen, 1991; Stock & Watson, 1993; Wooldridge, 2009) in the aggregate analysis utilising a panel dataset with 228 aggregated observations from 2002 to 2011 (EB57–75). The results obtained are complemented at the individual level.

Second, in addition to the standard macroeconomic variables – namely, inflation, unemployment and growth – we explore the role played by country-level and personal perceptions and attitudes exploiting information from a cross-sectional database with a maximum of 157,899 individual observations from 2002 to 2011 (EB 57–74).

Table 9.2 captures the support for the euro over time, controlling for country characteristics that are time-invariant, for swings in the error term and for feedback between the macro-determinants of support and support itself. By applying panel time series, we can be sure not to have omitted important variables.Footnote 6 The finding that the error terms are stationary (without systematic influence on support for the euro) implies that our coefficient estimates are unbiased and remain unbiased if further controls are added to the regression.

Table 9.2 shows the results for the determinants of support for the euro in a panel analysis covering 12 countries i (I = 12) and at different points of time t for the period from spring 2002 to spring 2011. We view this time period as the theoretically most appropriate one as from January 2002 onwards European citizens could actually use the euro as a real money in daily business. As we have argued above, a distinction of four different time periods seems to be appropriate, our analysis will include the third and fourth time period. Similar to other studies in the field (Gärtner, 1997, Kaltenthaler & Anderson, 2001; Banducci et al., 2009, Kaelberer, 2007 and Hobolt & Leblond, 2009), we expect that the price stability (inflation) should be a key influence on support for the euro. However, based on the popularity function literature we would also expect unemployment and growth of GDP per capita to exert a significant influence (see here e.g. Kaltenthaler & Anderson, 2001; Banducci et al., 2009 and Hobolt & Leblond, 2009).

Equation 1 in Table 9.2 includes inflation, unemployment and growth of GDP per capita as the explanatory variables and analyses our full sample. Inflation is negatively and significantly related to support for the euro at the 95% level. Growth of GDP per capita is not significantly related to support for the euro when estimating the observations in our full sample. Unemployment is negatively related with net support for the euro at the 90% level. As we have argued, the pre-crisis period (2002–08) should be kept distinct from the crisis period (2008–11). Eqs. 2 and 3 split the full sample into a pre-crisis period and a crisis period to explore the impact of the financial crisis on popular support for the euro.Footnote 7 Splitting the full sample into a pre-crisis period and a crisis period reveals that the significant negative effect of inflation on support for the euro is driven by the pre-crisis period in which inflation exhibits a strongly negative and significant (99% level) effect on support for the euro. As expected from the literature on popularity functions, GDP growth is strongly and positively associated with support for the euro in the pre-crisis sample. In the crisis sample, column 3, we detect no impact of the three macroeconomic variables on support for the euro. We thus conclude that inflation is the most robust driver of support for the euro.

So far we have examined the macroeconomic determinants of popular support for the euro over time (within effects). In Table 9.3 we move to a micro-level approach to analyse the impact of inflation – our main determinant of support for the euro – based on a cross-section analysis of respondents in all EA-12 countries. Controlling for the socio-economic variables of age, gender, education, left/right placement and the macroeconomic variables of unemployment and GDP growth per capita as well as for country and time fixed-effects (including 157,899 individual observations), inflation has the expected effect in all three samples. Respondents in a country with higher inflation tend to support the euro less than respondents who live in a country with more moderate inflation. Banducci et al. (2003) and Hobolt and Leblond (2009) argue that support is determined by both socio-tropic and egocentric motives. Citizens are on the one hand concerned about the situation in their country, while at the same time they also care about their personal situation. Moreover, Banducci et al. (2009) posit that the actual economic reality – as summarised in official economic statistics – does not necessarily agree with the perceived economic situation. Therefore, to account for citizens’ perceptions towards inflation, columns 2 and 3 include citizens’ perceptions towards their country’s situation (socio-tropic view) and their personal situation (ego-centric view).Footnote 8 Columns 2 and 3 analyse whether perceptions of inflation also have an impact on net support. Our results confirm that this is the case. All coefficients have the expected signs. In a cross-section design, however, the official inflation rate also affects euro support negatively and significantly in the crisis sample.

2.1 What Is Novel about Our Findings?

The literature has not yet analysed the impact of the financial crisis on citizens’ support for the euro. We find that the financial crisis – at least so far – has had no impact on public support for the euro when analysing aggregated data with a fixed-effects DFGLS panel analysis. Our findings from the pre-crisis period confirm a negative and significant relationship between inflation and support for the euro. For a pre-crisis sample, a similar result has been established, inter alia, by Banducci et al. (2009). In addition, in accordance with Banducci et al. (2009), perceived inflation also has the expected highly negative signs.

Beyond this consensus, we are able to show that on the aggregate level other variables, such as the budget deficit, the exchange rate, attitude towards the EU, euros in circulation, etc. are unable to influence the support for the euro in any consistent way. This result is in contrast to the findings of Banducci et al., 2003, 2009 and Hobolt & Leblond, 2009, who identify the exchange rate and the attitude towards EU membership as significant drivers of support for the euro.

Our analysis confirms that in contrast to a dramatic fall in citizens’ trust in the ECB (Roth et al., 2011b) driven by the financial crisis, public support for the euro has remained stable so far.

3 Conclusions

Our analysis shows that the financial and sovereign debt crisis that started in Europe in 2008 has not affected popular support for the euro within the euro area. This finding is in contrast to the pronounced fall in public trust and support for European institutions, the European Union per se and in particular the ECB, the central bank issuing the euro. At the aggregate level, support for the euro can be explained by adopting a popularity function approach, stressing the role of inflation and growth, when the economy runs smoothly as in normal times. During the recent crisis, these factors appear to no longer drive the support for the euro. Furthermore, we find no evidence that omitted variables (exchange rates, budget deficits, trust in the EU and European institutions) change our estimates.

The crisis has not reduced the support for the euro within the euro area. But outside the euro area, the public attitude towards the euro has become significantly more critical. Outside the euro area, the crisis is taken as proof that closer monetary integration is not the route to follow. Inside the euro area, the opposite holds.

To conclude, the European single currency, the euro, has so far enjoyed an astonishing overall support throughout the crisis, in sharp contrast to the pronounced fall in public trust in the ECB and also to the negative response among EU countries outside the euro area. This pattern is consistent with the view that Europeans in the euro area want the euro to continue to be their currency, while they are critical of the policies adopted by the ECB during the crisis. Thus, the data suggest that European public opinion does not hold the euro responsible for the crisis.

Notes

- 1.

During the 21-year period studied by us, this question has been modified slightly over time. The wording of EB 34–37 was “Within this European Economic and Monetary Union, a single common currency replacing the different currencies of the Member States in 5 or 6 years time”. The wording of the question from EB38 to EB40 was: “There should be a European Monetary Union with one single currency replacing by 1999 the (national currency) and all other national currencies of the Member States of the European Community”. After the ratification of the Maastricht Treaty, the wording in EB41 was changed to: “(…) Member States of the European Union and European Community”. From EB 42 onwards, “European Community” was dropped. From EB44 onwards, the “by 1999” was dropped. From EB 46 onwards, the “euro” is introduced and the wording “European monetary union” is taken out. From EB48 onwards, the word “should” is replaced by “has”. From EB54 the wording “replacing the (national currency) and all other national currencies” is dropped. From EB 54 onwards, “European Monetary Union” is reintroduced. From EB 56 to EB72 onwards, “There has to be” is dropped. The question in EB56 to EB72 represents the wording as highlighted within our main text. From EB73 onwards, “European Monetary Union” was replaced by “Economic and Monetary Union”. As we are of the opinion that these changes in the framing of the question over time are not responsible for any significant changes in the responses, we ignore these modifications of the survey question. A similar argument is made by Banducci et al., 2003, p. 690.

- 2.

- 3.

For a general discussion on the adequacy of using a “trust” or a “support” item in questionnaires, see Luhmann, 2000, p. 70.

- 4.

This result is consistent with evidence in Jonung and Conflitti (2008) on popular support for the euro.

- 5.

See the review of Jonung (2011) on public attitudes towards the single currency and European integration.

- 6.

According to the literature, important variables could be for example the budget deficit (debt-to-GDP ratio), the current account deficit, the exchange rate, the volume of euros in circulation and beliefs such as “EU membership is a good thing”, etc. (Banducci et al., 2003, 2009; Kaltenthaler & Anderson, 2001 and Gärtner, 1997).

- 7.

We have tested for cointegration in all periods (full sample/pre-crisis/crisis period) and found cointegration for the full sample and the pre-crisis period, but we did not find cointegration for the crisis period. Therefore, we can conclude that cointegration in the full sample period is driven by the data of the pre-crisis period. The finding of “no” cointegration in the crisis period is in line with our finding of insignificant coefficients for inflation, unemployment and growth in the crisis period. (Results are available upon request.)

- 8.

The best proxy for giving us information on individual perceptions about inflation is provided by the following question in the Eurobarometer surveys: “What do you think are the two most important issues (you are)/(OUR COUNTRY is) facing at the moment?” Several possible answers are then given, with “rising prices/inflation” and “unemployment” as two possibilities. The classic question asking about the “current situation” does not include inflation in the Standard Eurobarometers.

References

Banducci, S. A., Karp, J. A., & Loedel, P. H. (2003). The euro, economic interests and multi-level governance: Examining support for the common currency. European Journal of Political Research, 42, 685–703.

Banducci, S. A., Karp, J. A., & Loedel, P. H. (2009). Economic interests and public support for the euro. Journal of European Public Policy, 16, 564–581.

Brettschneider, F., Maier, M., & Maier, J. (2003). From D-mark to euro: The impact of mass media on public opinion on Germany. German Politics, 12, 45–64.

Eurobarometer (2009). Standard Eurobarometer 72, Autumn 2009. European Commission, DG Communication. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/browse/all/series/4961

Eurobarometer (2010a). Standard Eurobarometer 73, Spring 2010. European Commission, DG Communication. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/browse/all/series/4961

Eurobarometer (2010b). Standard Eurobarometer 74, Autumn 2010. European Commission, DG Communication. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/browse/all/series/4961

Eurobarometer (2011). Standard Eurobarometer 75, Spring 2011. European Commission, DG Communication. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/browse/all/series/4961

Gärtner, M. (1997). Who wants the euro – and why? Economic explanations of public attitudes towards a single European currency. Public Choice, 93, 487–10.

Gesis, Z. A. (2005). Data service. In Eurobarometer 1970-2004, CD-rom 1, ECS 1970-EB 41.1, Gesis, Man.

Giddens, A. (1996). Risiko, Vertrauen und Reflexivität. In U. Beck, A. Giddens, & S. Lash (Eds.), Reflexive Modernisierung (pp. 316–338). Frankfurt am Main.

Gros, D., & Roth, F. (2009). The crisis and citizens’ trust in central banks. VoxEu, 10 September.

Gros, D., & Roth, F. (2010). Verliert die EZB das Vertrauen der Bevölkerung. FAZ, 5 December.

Hobolt, S. B., & Leblond, P. (2009). Is my crown better than your euro? Exchange rates and public opinion on the European single currency. European Union Politics, 10, 202–225.

Jones, E. (2009). Output legitimacy and the global financial crisis: Perceptions matter. Journal of Common Market Studies, 47, 1085–1105.

Jonung, L. (2011). “Public attitudes towards the euro and European integration, a survey”, manuscript. Department of Economics, Lund University.

Jonung, L., & Conflitti, C. (2008). “Is the euro advantageous? Does it foster European feelings? Europeans on the euro after five years”, economic paper 313, April. DG ECFIN, European Commission. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/publication12337_en.pdf

Kaelberer, M. (2007). Trust in the Euro: Exploring the governance of a supranational currency. European Societies, 9, 623–642.

Kaltenthaler, K., & Anderson, C. (2001). Europeans and their money: Explaining public support for the common European currency. European Journal of Political Research, 40, 139–170.

Kirchgässner, G. (2009). “The lost popularity function: Are unemployment and inflation no longer relevant for the behaviour of German voters?”, CESIFO working paper no. 2882. CESIFO.

Köcher, R. (2010). Vertrauensverlust für den Euro. FAZ, 28 April.

Luhmann, N. (2000). Vertrauen. Lucius and Lucius.

Nannestad, P., & Paldam, M. (1994). The VP-function: A survey of the literature on vote and popularity functions after 25 years. Public Choice, 79, 213–245.

Roth, F. (2009). The effects of the financial crisis on systemic trust. Intereconomics, 44, 203–208.

Roth, F., Nowak-Lehmann D., F., & Otter, T. (2011a). “Has the financial crisis shattered citizens’ trust in the national and European governmental institutions?”, CEPS working document no. 343. Centre for European Policy Studies.

Roth, F., Gros, D., & Nowak-Lehmann D., F. (2011b). “Has the financial crisis eroded citizens’ trust in the European Central Bank? – Evidence from 1999–2010”, CEGE working papers 124. University of Göttingen.

Saikkonen, P. (1991). Asymptotically efficient estimation of Cointegration regressions. Econometric Theory, 7, 1–21.

Stock, J. H., & Watson, M. W. (1993). A simple estimator of Cointegrating vectors in higher order integrated systems. Econometrica, 61, 783–820.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2009). Introductory econometrics: A modern approach. South-Western Cengage Learning.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Comparison between net trust trend in the ECB and net support in the euro, 1999–2011

Notes: Net support levels above 0 indicate that a majority of citizens support the euro/trusts the ECB. Standard EB’s 51–75. As Special EB 71.1 (January/February 2011) has no information on support for the euro, it was not included in the time trend. However, it has to be pointed out that the inclusion of the special EB 71.1 would show a dramatic decrease/structural break of citizens’ trust in the ECB (see here also Gros & Roth, 2009, 2010, Roth, 2009 and Jones, 2009).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this license to share adapted material derived from this chapter or parts of it.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Roth, F., Jonung, L., Nowak-Lehmann D., F. (2022). The Enduring Popularity of the Euro throughout the Crisis. In: Public Support for the Euro. Contributions to Economics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86024-0_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86024-0_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-86023-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-86024-0

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)