Abstract

Using a panel of 17 Latin American countries for the period 2002–18, we study the impact of economic variables on government approval. Our empirical analysis shows that the one economic variable that appears consistently in all estimates is economic growth. More specifically, we show that for each point of additional growth, the approval rating increases between 1.1 and 1.9 percentage points. Other variables, such as inflation, government spending, and the composition of spending, are significant in only some of the specifications used, while growth is remarkably robust in all of them. Among non-economic variables, the lack of solid institutions also appears consistently as significant as well as the lagged value of government approval ratings. These results suggest that a program focused on growth has a positive influence on the popularity of the government. This conclusion is particularly relevant in a region where populism has been remarkably persistent over time and where the norm has been to run large budget deficits to gain popular support, with consequences on inflation and the external accounts.

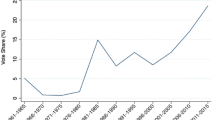

Source: Latinobarómetro

Source: Latinobarómetro and IMF World Economic Outlook (WEO) Database

Source: Latinobarómetro and ECLAC CEPALSTAT data base of social, economic and environmental indicators

Source: Latinobarómetro and Bloomberg

Source: Latinobarómetro

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

All databases are available in the following link https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/DIIYV3.

Code Availability

Stata code is available in the same link described above.

Notes

Our data indicate that Venezuela exhibits extreme variation in some variables, such as inflation. In fact, since 2014 Venezuela's inflation rate has exceeded 100%, and it reached 65,000% in 2018. We decided to exclude this country to avoid the classic sensitivity problem to outlier observations. Our decision is particularly important because of the instability of economic coefficients in the literature on vote-popularity functions (see Sect. "Literature review"). This decision is congruent with research that excludes Venezuela for this reason (see, for instance, IMF 2021).

Depending on the commodity, prices started a downward trend between 2011 and 2014.

See, for instance, the survey by Gronke and Newman (2003).

However, in the 2000 paper, the author finds that U.K. voters generally have a remarkably acute sense of macroeconomic improvement and decline.

Average government approval excludes the years 2012 and 2014, when the Latinobarómetro survey was not conducted.

The fiscal deficit in Latin America and the Caribbean was 2.3% of GDP in 2009, a big fall from a surplus of 1.6% in 2008 (IMF, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2020).

The countries are Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay.

The countries are Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costathat directly involve the president is from Martínez (2020). The victimization rate and the measure of distrust in institutions are from ECLAC statistical database; both variables are prepared by the ECLAC Social Statistics Unit, based on special tabulations from the Latinobarómetro database.

We decided to use random effects rather than fixed effects because the results of the Hausman test indicate that there is no evidence to reject the null hypothesis. In other words, we cannot rule out that there is no correlation between the unobserved effect and the explanatory variables. In this context, random- and fixed-effects estimators are consistent, but fixed-effects estimators are inefficient. The same conclusion is obtained for all the specifications of tables 3, 4, and 5.

However, this result is not robust as shown in the estimations below.

The results of the endogeneity test for fiscal spending measures indicate that it is not possible to reject the null hypothesis of exogeneity. However, we consider it necessary to show the results of the two-stage least squares estimations for three reasons. First, the theoretical justification for the endogeneity problem is plausible and thus needs to be addressed. Second, it is technically impossible to directly test the endogeneity of a variable since, by definition, the econometrician cannot observe the correlation between the variable and the unobservable error. Therefore, endogeneity problems cannot be ruled out categorically. Third, the two-stage approach allows us to compare across different statistical methods and to check the robustness of the results.

References

Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Review of Economic Studies, 58, 277–297.

Argyle, L. P., Arrajj, M., Skylar Covich, E. G., Garay, J. G., Hodges, H. E., & Smith, E. R. A. N. (2016). Economic performance and presidential trait evaluations: A longitudinal analysis. Electoral Studies, 43(September), 52–62.

Beck, N. (1991). The economy and presidential approval: An information theoretical perspective. In Norpoth, Lewis-Beck and Lafay.

Bellucci, P., & Lewis-Beck, M. S. (2011). A stable popularity function? Cross-national analysis. European Journal of Political Research, 50(2), 190–211.

Berlemann, M., & Enkelmann, S. (2014). The economic determinants of U.S. Presidential approval: A survey. European Journal of Political Economy, 36(December), 41–54.

Carlin, R. E., Hartlyn, J., Hellwig, T., Love, G. J., Martínez-Gallardo, C., & Singer, M. M. (2018). Public support for Latin American presidents: The cyclical model in comparative perspective. Research & Politics, 5(3), 1–8.

Carlin, R. E., Hellwig, T., Love, G. J., Martínez-Gallardo, C., & Singer, M. M. (2021). When does the public get it right? The information environment and the accuracy of economic sentiment. Comparative Political Studies, 54(9), 1499–1533.

Carlin, R. E., Love, G. J., & Martínez-Gallardo, C. (2015). Cushioning the fall: Scandals, economic conditions, and executive approval. Political Behavior, 37(1), 109–130.

Cerda, R., & Vergara, R. (2007). Business cycle and political election outcomes: Evidence from the Chilean democracy. Public Choice, 132(1), 125–136.

Cerda, R., & Vergara, R. (2008). Government subsidies and presidential election outcomes: Evidence for a developing country. World Development, 36(11), 2470–2488.

Choi, I. (2001). Unit root tests for panel data. Journal of International Money and Finance, 20, 249–272.

Choi, S.-W., James, P., Li, Y., & Olson, E. (2016). Presidential approval and macroeconomic conditions: Evidence from a nonlinear model. Applied Economics, 48(47), 1–15.

Cuzán, A. G., & Bundrick, C. M. (1997). Presidential popularity in Central America: Parallels with the United States. Political Research Quarterly, 50(4), 833–849.

Dicle, Betel, & Dicle, Mehmet F. (2011). Presidential approval models revisited: A new perspective. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1927985

Dornbusch, R., and Edwards, S. (1989). Macroeconomic Populism in Latin America. Working Paper No. 2986. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Duch, R. M., & Stevenson, R. (2010). The global economy, competency, and the economic vote. The Journal of Politics, 72(1), 105–123.

Enkelmann, S. (2014). Government popularity and the economy: First evidence from German microdata. Empirical Economics, 46(3), 999–1017.

Fair, R. C. (1978). The effect of economic events on votes for president. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 60(2), 159–173.

Fair, R. C. (1996). The econometrics of presidential elections. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10(3), 89–102.

Ferreira, A. L., & Sakurai, S. N. (2013). Personal charisma or the economy? Macroeconomic indicators of presidential approval ratings in Brazil. Economía, 14(3), 214–232.

Fox, G., & Phillips, E. N. (2003). Interrelationship between presidential approval, presidential votes, and macroeconomic performance, 1948–2000. Journal of Macroeconomics, 25(3), 411–424.

Goodhart, C. A. E., & Bhansali, R. J. (1970). Political economy. Political Studies, 18, 43–106.

Gronke, P., & Newman, B. (2003). FDR to Clinton, Mueller to? A field essay on presidential approval. Political Research Quarterly, 56(4), 501–512.

Hardie, I., Henderson, A., & Rommerskirchen, C. (2020). The impact of treasury yields on U.S. presidential approval, 1960–2010. New Political Economy, 25(6), 1022–1040.

Hibbs, D. A., Jr., Rivers, R. D., & Vasilatos, N. (1982). On the demand for economic outcomes: Macroeconomic performance and mass political support in the United States, Great Britain, and Germany. The Journal of Politics, 44(2), 426–462.

Hibbs, D. A., Jr., & Vasilatos, N. (1981). Economics and politics in France: Economic performance and mass political support for Presidents Pompidou and Giscard d’Estaing. European Journal of Political Research, 9(2), 133–145.

Inman, Robert P. (1988). Federal assistance and local services in the United States: The evolution of a new federalist fiscal order. In Harvey S. Rosen (Ed.), Fiscal federalism: Quantitative studies. University of Chicago Press.

Inman, R. P., & Fitts, M. A. (1990). Political institutions and fiscal policy: Evidence from the U.S. historical record. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 6, 79–132.

International Monetary Fund. (2021). A long and winding road to recovery. Regional Economic Outlook: Western Hemisphere.

Johnson, G. B., & Schwindt-Bayer, L. A. (2009). Economic accountability in central America. Journal of Politics in Latin America, 1(3), 33–56.

Jovel, J. R. (1989). Natural disasters and their economic and social impact. CEPAL Review, 38(August), 133–145.

Jung, J. W., & Oh, J. (2020). Determinants of presidential approval ratings: Cross-country analyses with reference to Latin America. International Area Studies Review, 23(3), 251–267.

Kagge, R. (2018). Asymmetric evaluations: Government popularity and economic performance in the United Kingdom. Electoral Studies, 53(June), 133–138.

Khan, A., Chenggang, Y., Khan, G., & Muhammad, F. (2020). The dilemma of natural disasters: Impact on economy, fiscal position, and foreign direct investment alongside belt and road initiative countries. Science of the Total Environment, 743(November), 140578.

Kramer, G. H. (1971). Short-Term Fluctuations in U.S. Voting Behavior, 1896–1964. American Political Science Review, 65(1), 131–143.

Lafay, J. D. (1984). Political change and stability of the popularity function: The French general election of 1981. Political Behavior, 6(4), 333–352.

Lewis-Beck, M. S. (1980). Economic conditions and executive popularity: the French experience. American Journal of Political Science, 24, 306–323.

Lewis-Beck, M. S. (1983). Economics and the French voter: A microanalysis. Public Opinion Quarterly, 47(3), 347–360.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., & Lobo, M. C. (2017). The economic vote: ordinary vs. extraordinary times. In K. Arzheimer, J. Evans, & M. S. Lewis-Beck (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of electoral behaviour (pp. 606–30). Sage.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., & Paldam, M. (2000). Economic voting: An introduction. Electoral Studies, 19, 113–121.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., & Stegmaier, M. (2008). The economic vote in transitional democracies. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 18(3), 303–323.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., & Stegmaier, M. (2013). The VP-function revisited: A survey of the literature on vote and popularity functions after over 40 years. Public Choice, 157(3–4), 367–385.

MacKuen, M. B., Erikson, R. S., & Stimson, J. A. (1992). Peasants or bankers? The American electorate and the US economy. American Political Science Review, 86(3), 597–611.

Martínez, C. A. (2020). Presidential instability in Latin America: Why institutionalized parties matter. Government and Opposition. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2020.18

Mueller, J. (1970). Presidential popularity from Truman to Johnson. The American Political Science Review, 64(1), 18–34.

Mueller, J. (1973). War, presidents, and public opinion. John Wiley & Sons.

Murillo, M. V., & Visconti, G. (2017). Economic performance and incumbents’ support in Latin America. Electoral Studies, 45(February), 180–190.

Nannestad, P., & Paldam, M. (1994). The VP-function: A survey of the literature on vote and popularity functions after 25 years. Public Choice, 79(3), 213–245.

Nickelsburg, M., & Norpoth, H. (2000). Commander-in-chief or chief economist? The president in the eye of the public. Electoral Studies, 19(2–3), 313–332.

Niou, E. M. S., & Ordershook, P. C. (1985). Universalism in congress. American Journal of Political Science, 29(2), 246–258.

Norpoth, H. (1984). Economics, politics, and the cycle of presidential popularity. Political Behavior, 6(3), 253–273.

Paldam, M. (1991). How robust is the vote function? A study of seventeen nations over four decades. In Norpoth, Lewis-Beck and Lafay.

Peltzman, S. (1992). Voters as fiscal conservatives. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(2), 327–361.

Sachs, Jeffrey D. (1989). Social conflict and populist policies in Latin America. Working Paper No. 2897. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Sanders, D. (1996). Economic performance, management competence and the outcome of the next general election. Political Studies, 44(2), 203–231.

Sanders, D. (2000). The real economy and the perceived economy in popularity functions: How much do voters need to know? A study of British data, 1974–97. Electoral Studies, 19(2–3), 275–294.

Singer, M. M. (2013). Economic voting in an era of non-crisis: The changing electoral agenda in Latin America, 1982–2010. Comparative Politics, 45(2), 169–185.

Singer, M. M., & Carlin, R. E. (2013). Context counts: The election cycle, development, and the nature of economic voting. The Journal of Politics, 75(3), 730–742.

Stigler, G. (1973). General economic conditions and national elections. American Economic Review, 63(2), 160–167.

Wagner, Adolph. (2016). Grundlegung der Politischen Oekonomie, Bk. VI, 32. Reprint. Norderstedt, Germany: Hansebooks.

Weingast, B. (1979). A rational choice perspective on congressional norms. American Journal of Political Science, 23(2), 245–262.

Whiteley, P. F. (1986). Macroeconomic performance and government popularity in Britain: The short run dynamics. European Journal of Political Research, 14(1–2), 45–61.

Wlezien, C., Franklin, M., & Twiggs, D. (1997). Economic perceptions and vote choice: Disentangling the endogeneity. Political Behavior, 19(1), 7–17.

Zechmeister, E. J., & Zizumbo-Colunga, D. (2013). The varying political toll of concerns about corruption in good versus bad economic times. Comparative Political Studies, 46(10), 1190–1218.

Acknowledgements

We thank Carlos Madeira, Catalina Morales, Estéfano Rubio, and two anonymous referees for their valuable comments and suggestions; Roberto Cases for very able research assistance; and Natalia Gallardo, who worked with us on an earlier version of this paper. Data and software code necessary to reproduce the numerical results are available in https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/DIIYV3.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cerda, R., Vergara, R. Economic Growth and Political Approval Ratings: Evidence from Latin America. Polit Behav 45, 1735–1758 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09798-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09798-y