Abstract

This chapter reviews the evidence of the impact on children’s education from the school closures, implemented over the period March-June 2020, as part of the lockdown measures put in place to control the spread of the Covid-19 virus. The sources of information are surveys of the adult population, parents/guardians of school-age children, teachers and students based on representative samples as well as achievement tests that were accessible by early 2021. The lockdowns and associated closures of schools implemented in response to the arrival of the Covid-19 pandemic represented a sudden and unprecedented event for which school authorities, teachers, parents, and students were unprepared. While distance and remote education arrangements were put in place at short notice, they represented an imperfect substitute to in-person schooling. In the short-term, the consequences of school closures and lockdowns appear to have been modest in scale and impact in the reviewed countries. For most (though by no means for all) children, missing 8–18 weeks of face-to-face schooling appears not to have had dramatic consequences for either their academic or broader development, or led to the significant widening of pre-existing inequalities. However, a definitive assessment of the impact of the school closures in the first half of 2020 will not be possible for some time.

William Thorn and Stéphan Vincent-Lancrin are Senior Analysts at the OECD Directorate for Education and Skills. The analyses given and the opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the OECD and of its members. Vivien Liu and Gwénaël Jacotin are gratefully acknowledged for excellent research and statistical assistance.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

15.1 Introduction

The objective of this chapter is to offer some insight into the impact on children’s education from the school closures, implemented over the period March-June 2020, as part of the lockdown measures put in place to control the spread of the Covid-19 virus. The sources of information are surveys of the adult population, parents/guardians of school-age children, teachers, and students, as well as achievement tests that were accessible by early 2021. The information was collected during the period of lockdown or close thereafter. The focus is on evidence from surveys and studies based on representative probability samples—that is, from surveys collecting information from samples designed to be representative of clearly defined target populations. The exception is the discussion of the results of academic achievement tests. The corpus of studies meeting this condition is surprisingly small, even in high-income countries. Consequently, most of the information comes from five countries: France, Ireland, England, and the United Kingdom (UK), and the United States (US) (see Annex A for details). Depending on the topics, the picture is supplemented by information from Australia, Belgium (Flanders), Italy, and the Netherlands. The picture that is drawn is inevitably partial, not only geographically, but also thematically as the studies from which information has been drawn were developed or adapted very quickly to collect information on a range of topics related to the experience and behaviour of individuals and households during lockdown.

The combination of the closure of schools and the broader lockdown/confinement measures affected the life of children and their families, transforming children’s educational experience during the duration of confinement. The setting in which education took place moved from school buildings to the family home for most children. The mode of instruction shifted from face-to-face contact with teachers/instructors to some form of remote learning, often supervised by parents. The home and social environment of children was also affected in many ways that, in its turn, may have affected the educational experience of children. In-person contact with people other than household members was severely restricted. The working arrangements of many parents changed, often dramatically. Many were laid-off on a temporary or permanent basis and many others had to work from home. In addition, parents faced a range of stresses associated with the pandemic: about the health of family and friends, the education of their children, their work, and finances.

While related and interacting with one another, two different aspects of the health crisis should be separated: (1) school closures and education continuity from home (or under new arrangements) for children, and (2) the general social and family environment in which this took place. While the latter is also relevant to the experience of learning under lockdown, the focus of this chapter is the first aspect. Two broad issues regarding school closures are explored: the nature of the educational experience of primary and secondary education students during the period of school closures, and the effect of school closures on students learning.

The presentation covers four main topics: aspects of schooling during lockdowns; learning time during school closures; parental and family involvement in children’s learning; and the positive and negative aspects of home learning. The focus on these topics reflects the fact of which data is available. At the same time, they represent topics of considerable interest for policy makers and analysts wishing to understand the experience of school education during lockdown and its consequences (which is itself one of the reasons that data was collected on them). Whenever possible, the equity dimension (the differences in the experience of pupils from different social backgrounds) is explored.

The approach adopted is deliberately descriptive. This is an inevitable consequence of the small number of countries from which data is available, as well as the partial nature of the data available. While a detailed comparative analysis of the experience and outcomes of Covid-related school closures in different countries would be fascinating, the data does not permit it at this time. The point is rather to present the available information from good quality studies on topics relevant to understanding the experience of learning during school closures with the aim of empirically grounding examination and discussion of these issues in actual examples.

15.2 Aspects of Schooling During Lockdowns

15.2.1 School Building Closures Meant that Most, but not All Students, Changed the Location and Form of Their Schooling

In most, though not all, countries across the world, the measures implemented to control the spread of the Covid-19 virus during the “first wave” of the pandemic from late February to June 2020 involved generalised “lockdowns”—restrictions on movement and the size of gatherings (public and private), the closure of a range of businesses and other institutions, including schools and other educational institutions such as vocational colleges and universities. The duration of school closures over the period February to the end of June 2020 (the end of the school year in the northern hemisphere) was between 0 and 19 weeks (including vacations) in OECD countries, depending on the level of schooling. Accounting for vacations in this period (around 2–3 weeks in most countries), closures meant the substitution of 4–9 weeks of face-to-face instruction with home-based learning in most OECD countries (OECD, 2021). In those countries in which schools were reopened for face-to-face instruction before the end of the 2019–20 school year, the reopening of schools was often staggered. Different year groups returned at different dates and pupils did not necessarily return on a full-time basis. In addition, some parents continued to keep their children at home even if they belonged to the age or year groups eligible to return to school. In some countries, schools continued to be closed from the end of July in the southern hemisphere or did not reopen at the start of the 2020–21 school year.

The closure of schools did not mean that all children undertook their schooling at home. In some countries (including those covered in this chapter), the children of so-called “key” or “essential” workers, of parents who had difficulty looking after children at home during usual school hours, and children in vulnerable circumstances could continue to attend school in-person. The available information suggests considerable variations between countries regarding the proportion of children that attended school in-person during lockdowns. In England, the numbers of children attending school on any day during lockdown were low. From 20 March 2020 until 1 June 2020 when schools started to reopen, between 1 to 3% of enrolled pupils attended school in-person on any day (Gov.uk, 2020), with around 7% of parents in one study reporting that their child aged 5–16 years had attended school in-person during lockdown (NHS Digital, 2020, Table 4.1). In Australia,Footnote 1 17% of parents/guardians reported that the child in their household attended school in-person (ABS, 2020, Table 3.1). In France, 31% of primary schools, 25% of lower secondary schools, and 6% of upper secondary schools remained open for attendance by children of essential workers (Barhoumi et al., 2020, Fig. 7.1), but the number of students involved are not available.

In many countries, there was also a small group of children whose mode of learning was not directly affected by school closures—around 3% of school enrolments in the United States, where the phenomenon is the most widespread (Snyder, de Brey & Dillow, 2019, Table 206.10),Footnote 2 and less than 1% in other countries—e.g., Australia (Chapman, 2020), France (Assemblée Nationale, 2019), and England (Office of the Schools Adjudicator, 2020).

15.2.2 Instruction and Instructional Materials Were Mainly Online or Paper-Based, Although Classes Were Sometimes Cancelled

One of the features of schooling during school closures was the use of online resources and tools to deliver lessons and instructional materials, and to communicate with students. What was the balance between the use of online resources and tools to deliver lessons, access, transmit, and receive instructional materials and student work compared to other, more ‘traditional,’ means?

The use of online tools and platforms was the predominant mode of delivery of lessons and learning materials for students undertaking their education at home (see Annex B, Table 15.10), primarily through dedicated educational platforms, applications, or e-mail. Real time interaction with teachers represented a relatively small component of the educational experience of schoolchildren during school closures. In the United Kingdom, 25% of parents reported that their child had received real-time interactive learning in the previous seven days, while in England, 32% of parents reported that their child had received one or more online live lesson per day. Fourteen percent of German teachers stated that they had taught classes by video calls. In the US, the average total time spent by all students in households in contact with teachers was 4 h per week (see Table 15.4 below).

Paper materials provided by schools were also used by a reasonably sized minority of students, in most cases in conjunction with digital materials. In France, 11% of students received learning materials in the form of printed documents. In the US, 19–21% of parents/guardians reported that their child’s classes had moved to a distance format using paper materials. Higher rates of usage of paper materials were reported in the United Kingdom, where 34% of children who were home-schooled used some non-digital resources provided by their school. From the supply side, teachers in Germany reported that 33% of learning resources were shared in the form of hardcopies via post or pickup, and 54% of US teachers reported using hardcopy materials as part of distance learning.

The extent of the use of online tools and resources for the delivery of instruction and materials increased with the age of pupils and level of education. The proportion of teachers in France suggesting activities to students that required use of a computer connected to the internet was lowest at primary level and highest at upper-secondary level (see Annex B, Table 15.10). In the United Kingdom, the proportion of children using of school-provided real-time interactive online learning increased with the age of the oldest child and the use of school-provided non-digital resources declined (ONS, 2020, Table 2). Similarly, the share of students having one or more online live lesson per day in the United Kingdom was higher for secondary students (36%) than for primary students (27%) (Benzeval et al., 2020).

The United States is the only country in which there is information on the use of different modes of remote instruction by parental characteristics. The proportion of households in which some or all of children’s classes moved to a distance learning format using online resources increased with the educational attainment of the respondent and household income; it was also associated with ethnic background. Classes were more likely to have moved to online delivery among households in which the respondent was white or Asian (78% and 82% respectively), than Black (65%) or Latino/Hispanic (72%) (US Census Bureau, 2020, Education Table 2).

The positive relationship between education and income and being a member of a Black or Hispanic/Latino household, and the probability of some or all of children’s classes moving to online delivery may have reflected a deliberate choice on the part of their schools to use paper-based materials due to the difficulty (real or perceived) for their students to access materials online. The data suggests, however, that rather than compensate for difficulties with online access by using paper-based materials, schools may have chosen simply to cancel some classes. There were only small differences in the proportion of households in which some or all of children’s classes moved to a distance learning format using paper materials sent home according to the characteristics of the respondent. At the same time, children in low-educated and low-income households and children in Black and Hispanic/Latino households were more likely than children in more advantaged households to have some or all their classes cancelled.Footnote 3

15.2.3 Access to Digital Devices and Networks Was Limited for a Sizeable Minority of the Population

Given the reliance on online delivery of instruction, learning materials, and online communication between students and teachers, access to the necessary devices and networks was essential for students to continue their schooling successfully. What evidence is there regarding access to digital devices and the Internet during the period of school closures and the extent to which access was related to student’s socioeconomic background?

A substantial minority of households and students (Table 15.1) experienced difficulties with access.

Unsurprisingly, access to digital devices and a reliable internet connection was related to social background. In the United Kingdom, lack of devices was more often cited by parents as a reason for their children struggling to continue their education in low-income households than high-income ones. However, no clear relationship with level of parental education was observed (ONS, 2020, Table 4). In the United States, the proportion of parents reporting that it was very or somewhat likely that their child would encounter at least one of three digital obstacles to doing their schoolwork at home (“needing to use a cell phone,” “using a public Wi-Fi network because no reliable internet at home,” and “being unable to complete schoolwork because they did not have access to a computer at home”) decreased with family income (Horowitz, 2020). The share of households with children in public or private schools with a computer always available for educational purposes also increased with household income (US Census Bureau, 2020, Education Table 3). Teachers in the United States working in high poverty schools were significantly more likely to report that their students lacked access to the internet and devices at home (Stelitano et al., 2020). The school or school district played an important role in the provision of computers for use by students in the US. Around 40% of parents/guardians reported that the child in their household had access to a computer provided by the children’s school or school district for use outside school (US Census Bureau, 2020, Education Table 4). The use of a computer supplied by the school or school district was highest among households headed by low-educated and low-income adults and in households headed by Blacks, Hispanics, and Latinos. The importance of the school in the provision of devices in the US is confirmed by a survey in late April/early May 2020, in which 78% of teachers indicated that their school provided students with devices (Stelitano et al., 2020). In contrast, in the United Kingdom, only 5% of parents who “home-schooled” their eldest/only child indicated that their child used a device provided by the school and 73% stated that they provided a device for their child (ONS, 2020, Table 2). Unfortunately, data on the source of the devices used by children to access instructional material and communicate with their school are not available for the other countries covered, which may reflect the fact that the provision of computers by schools was uncommon.Footnote 4

15.2.4 Teachers May Have Lowered Their Ambitions Regarding the Content of Instruction

The closure of school buildings meant that the delivery of education had to be adjusted to allow (most) students to continue their education in their homes. There is evidence from France and the United States that the content and focus of instruction and the amount of work pupils were expected to do was also adjusted to reflect the new circumstances of learning.

French teachers reported that the main priority of their school during the period of closure was to preserve their pupils’ link with learning (53% of primary school and 58% of secondary school teachers), rather than to continue to advance with the teaching programme (cited by 5% of primary and 7% of secondary teachers) or the consolidation of students’ learning (cited by 23% of primary and 12% of secondary teachers) (Barhoumi et al., 2020, Figs. 6.1 and 6.4). The results of the survey of US teachers in late April/early May 2020 suggest that they adjusted their expectations in similar ways. Only 12% of teachers reported covering all, or nearly all, of the curriculum that they would have covered had their building remained open. In response to the question of whether they were focusing on reviewing content that was taught before Covid-19 versus presenting new content, 46% indicated that they were focussing mostly or exclusively on review rather than introducing new content (Hamilton, Kaufman and Diliberti, 2020).

15.3 Learning Time During School Closures

An important indicator of the effect of school closures and the associated changes to the mode of instruction on pupils’ learning is the amount of time that school students devoted to educational activities during this period. This can be compared with normal instruction time at school to give an idea of the impact on the quantity of learning. While informative, some caution is advised in making such comparisons. On the one hand, the estimates of learning time at home are likely to be subject to reasonably large measurement errors as they are usually provided by parents, who may have an inexact understanding of how much time their children (especially older children) spent on schoolwork. On the other, official instruction time is not an error-free measure of the time pupils devote to learning either. Children attending classes are engaged in learning to varying degrees (from staring out the window to giving full attention to the lesson). In addition, in normal times, many students undertake schoolwork at home in the form of self-study, homework, and preparation for exams and tests.

15.3.1 Around 10 to 20% of Students May Have Stopped Their School Learning Activities

There is evidence that a small, though by no means negligible, proportion of students stopped (school-related) learning activities during the period of school closures. One measure of this is the proportion of students with whom schools had no contact. In the Czech Republic, schools lost contact with over 20% of upper-secondary students enrolled in the vocational track, and between 15 to 20% of students enrolled in primary and lower-secondary education (CSI, 2020). Smaller proportions of children were ‘lost’ to the system in France, where teachers estimated that they had lost contact with 6% of primary school students and 10% of secondary students in their classes while schools were closed (Barhoumi et al., 2020, Figs. 1.9 and 1.10). In line with these estimates, 8% of parents of French high school students indicated that their child had not done any schoolwork set by their teachers during the period of school closures (Barhoumi et al., 2020, Fig. 2.8). In the United Kingdom, 17% of 16–18-year-olds in full-time education surveyed between 7 May and 7 June 2020 indicated that they had not continued with their education in the previous weekFootnote 5 (ONS, 2020, Table 5).

In addition, there were children who did not receive any schoolwork from their schools. In the United Kingdom, for example, around 10% of parents of schoolchildren reported that their child had not received schoolwork to complete at home in April 2020 (Eivers, Worth & Ghosh, 2020). The proportion was highest for children in upper-secondary schooling. Around 25% of the parents of children in Key Stages 4 and 5 (years 10–12) indicated that their child received no schoolwork. For children preparing for exams (e.g., GSCE and A-levels), this may have reflected the fact that they had already covered the relevant curricula by the time schools had closed and there was no need to undertake further study during a period normally devoted to exam revision. In other data from the United Kingdom, 25% of parents reported that children who were educated at home had not undertaken activities using materials provided by their school in the preceding week (ONS 2020, Table 2). It is not possible to determine whether this was because no schoolwork was provided or because children and/or their parents decided not to use it.

15.3.2 Students Spent About Half Their Normal “in-Person” Time on School-Related Learning Activities

The amount of time students spent on schoolwork during the period of school closures is a topic covered in several surveys. The data collected is not completely comparable, however, in terms of the definitions of schoolwork, the reference period (an average day, the previous week), or the exact populations covered. For this reason, Tables 15.2, 15.3 and 15.4 present the available information separately for France and Ireland (Table 15.2), the United Kingdom (Table 15.3), and the United States (Table 15.4). In each of the countries concerned, the source of the estimates is a parent/guardian or another adult in the household.

The situation in the United Kingdom is very similar to that in France and Ireland. At the primary level (ages 5–10), the estimated average hours per day devoted to schoolwork by students during lockdown was 2 and 2.4 h depending on the data source. At the secondary level, the estimates were between 3.0 and 3.2 h (Table 15.3).

In the United States (Table 15.4), an average of 23 h per calendar week was spent on learning/teaching activities per household. A direct comparison of this figure with the estimates in England, France, and Ireland is impossible for two main reasons: (1) it represents the sum of the hours spent by all children in the household on learning activities and all hours spent by all household members on teaching activities with children rather than hours per individual child, and (2) learning/teaching activities are not limited to those based on materials or lessons provided by schools.

In France, Ireland, the United Kingdom, and the United States, the school week generally involves around 4.5–6 h of instruction time per day (23–30 h per week) depending on the country (and in the United States and the United Kingdom, states or regions within countries and even individual schools) and the level of schooling (see for France, Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale, 2021; for Ireland: Gov.ie, 2019; and for the US: NCES, n.d., Table 15.14). Thus, in the four countries for which we have data, the average amount of time (per day or per week) that school pupils spent on schoolwork (however defined) during the period of school closures was less than the hours of instruction time that they would have received at school in ‘normal’ conditions. In England, France, and Ireland (unfortunately the US data does not lend itself to such a calculation), this represents about half the usual instruction time (about 3 h compared to the 5–6 h of formal instruction per day, depending on the level of schooling). In addition, as noted above, in ‘normal’ conditions, many students would also spend some time undertaking additional schoolwork or study activities at home.

As can be seen from Tables 15.2 and 15.3, there was considerable variation in the time spent on schoolwork by individual children. In normal conditions, the time spent by pupils being instructed in classes will not vary greatly, as this is set by the school timetable and the relevant regulations. Variation in the time devoted to schoolwork will be due largely to time spent on schoolwork at home by students (e.g., in the form of study, revision, homework, completion of assignments, etc.). In the period of school closures, time spent on schoolwork was to a greater or lesser extent determined by the students themselves and their parents as opposed to the ‘institutional constraints’ of timetabled classes.

15.3.3 Time on Schoolwork Shows no Strong Relationships with Parental Education or Household Income

The time children spent on schoolwork during school closures shows no clear relationship with either the level of education of parents/guardians (Table 15.5), household income, or ethnicity.

Of the four countries for which data is available regarding the level of education of parents/guardians, the United States is the one country in which hours of schoolwork (in this case, total hours of live contact with teachers and hours spent on their own learning by children in the household) shows a positive relationship with the education level of parents/guardians.

Data on hours of schoolwork during school closures is available by the respondent’s income (UK) and household income (US), and by ethnic background (US). Hours of schooling are highest for students with a parent in the highest income group in the United Kingdom (ONS, 2020, Table 2), but no association exists between household income or ethnicity and hours of schoolwork in the United States (US Census Bureau, 2020, Education Table 1).

15.4 Parental and Family Involvement

Given the limited direct contact students had with teachers, parents and guardians had to take over much of the role of the supervision of their children’s education (including instruction) during the period of school closures. In this section, we explore the role parents, guardians, and other family members played in the education of children. What proportion of parents assisted their children and how much time did they spend doing so? What assistance did they provide and how comfortable were they with supporting their children’s education?

15.4.1 Younger Children Received More Assistance from Parents

Data on whether parents/guardians assisted their children with their schooling during lockdown is available for France, the United Kingdom, and the United States (Table 15.6). The French data refers to the proportion of students reporting that they were assisted by their parents, and the UK data to the proportion of parents reporting that they “home-schooled” their eldest/only child. High proportions of parents/guardians aided with their children enrolled in primary and lower secondary education. In both countries, the proportion of parents assisting their children declined with the age of the child and the child’s level of education. This is likely to reflect the greater autonomy and independence of older children and the lesser expertise of parents concerning the content of the curriculum in the later years of high school.

In France and the United Kingdom, in addition to having a greater probability of receiving assistance from their parents/guardians, younger children (in lower grades) also received more assistance than older children (in higher grades). The time devoted by parents to assisting their children per day decreased as the level of their children’s schooling increased (Table 15.7). A large proportion of parents in both countries reported that they provided very little support to children enrolled in academically oriented upper-secondary education. In France, 40% of parents of students in lower-secondary education and 70% of parents of students in upper-secondary general education assisted their children for less than 30 min per day. In the United Kingdom, 60% and 90% of parents for lower- and upper-secondary students respectively assisted their children for less than an hour per day. The average time devoted by parents in the United Kingdom to assisting children is estimated to be 2 h per day (of assistance) to primary school children and 0.9 h per day for secondary students (Pensiero et al., 2020). In the United States, the total average time devoted to teaching activities during school closures by parents/guardians was around 12 h per week – per household rather than per parent (see Table 15.4).

As expected, the amount of time parents devoted to assisting children with schoolwork was higher for most (but not all) parents during the period of school closures than was usually the case. Overall, 65% of the parents of French high school students said that they spent more time than usual during confinement helping their children with schoolwork, 21% as much time as usual, and 8% less time (Barhoumi et al., 2020, Fig. 5.5). In Italy, two thirds (67%) of adults who cared for children of 0–14 years of age during lockdown reported spending more time in childcare activities (both homework and play) compared to an average pre-Covid day, 30% the same amount, and 3% less time (Istat, 2020, Fig. 4).

There is little evidence of a close relationship between parental socio-economic status and the provision of assistance by parents in the available studies. In the United Kingdom, no relationship is observed between the level of parental education or income and the “provision of home schooling” (ONS, 2020, Table 2) or the hours of assistance provided by parents (Benzeval et al., 2020). A similar picture is seen in the United States, where no clear relationship exists between either parental education or income and the total hours spent by household members on teaching children (US Census Bureau, 2020, Education Table 1), or between income and the provision of additional instruction and resources (Horowitz, 2020). This is somewhat contrary to expectations. However, it is possible that parents with higher levels of education and income had less available time to assist their children during the period of lockdown than their less-educated and lower-paid counterparts. The incidence of temporary inactivity (e.g., furlough, temporary layoff) during lockdowns was lowest for employees in management and professional occupations—i.e., occupations associated with high levels of education and high incomes.

15.4.2 Around Half or Less of Parents Felt Capable to Assist with Their children’s Remote Education

The shift of the setting of school education to the home placed a large responsibility on parents/guardians for supervising and guiding their children’s education. How comfortable with and prepared for the role were parents/guardians?

In both the United Kingdom and the United States, slightly less than half of the parents/guardians of school children appeared comfortable in their ability to support the home schooling of their children. At the end of April 2020, only 45% of parents/guardians in the United Kingdom agreed that they were confident in their abilities to support schoolwork of their children within their household, even if a much larger share (75%) believed that they had access to the resources they needed to help them “home school” their children/child well (ONS, 2020, Table 1). In a national survey of parents of K-12 students in the United States, 56% of parents reported that their child’s remote learning had been difficult or very difficult for themselves and their spouse/partner (Jones, 2020b). Consistent with this, in May 2020, two-thirds (68%) of US parents reported that knowing how to teach children in ways they could learn had been a challenge in terms of the remote distance education of their child (Jones, 2020a).

Very similar results were found in France. Around half or more of French parents of secondary students had some problems finding the time to assist children (51%) and helping their children understand lessons (48%), with slightly lower proportions having at least some problems helping their child understand instructions from teachers (42%) or finding information about the schoolwork that needed to be completed (40%) (Barhoumi et al., 2020, Fig. 5.4).

In Ireland, parents seemed even less confident (CSO, 2020). When asked in August 2020 whether they were concerned about their capacity to provide adequate home learning support if their child’s primary school was closed in the new school year, 85% of Irish parents of primary school students indicated that they had some concerns, with 51% being very or extremely concerned.

The available evidence regarding the relationship of socio-economic status and parents’ perceptions of their ability to provide support for their children’s education is ambiguous, if not contradictory. In the United Kingdom, parents with higher degree qualifications were more likely than other parents to agree that they were confident in their abilities to “home school” the children/child within their household. However, confidence in the ability to support children in their remote schooling was unrelated to income (ONS, 2020, Table 1). In contrast, in Ireland, parents with higher education qualifications were more likely to be ‘very’ or ‘extremely’ concerned about their ability to provide adequate home learning support if schools were closed in the new school year than parents with a highest qualification at secondary level or lower, and less likely to be “not at all” concerned (CSO, 2020). The reasons for the differences in the views of highly educated parents in the UK and Ireland must remain the object of speculation.

15.5 Home Learning: The Positives and Negatives

Did the arrangements put in place to support home learning during school closures allow children to maintain their link with schools and teachers and to continue to learn effectively? Two main types of information relevant to this question exist. First, there is the perception of actors involved. Several surveys sought the views of parents concerning the support provided to their children during the period of closures and remote learning and the difficulties experienced by their children. Second, there are a small number of studies that have compared results on standardised tests for students in the cohorts affected by the pandemic with results for students in the same tests in previous years.

15.5.1 Parents Had Mixed Views: They Were Appreciative of Schools’ Efforts, but Very Concerned About Their children’s Learning

How satisfied were parents with the home-schooling experience and the support offered by schools, and how did they assess the impact of the period of home schooling on children’s learning and social development? Overall, parents/guardians had mixed views. On the one hand, for the most part, they considered that their children had continued with their education and appreciated the efforts made by schools and teachers during the period of school closures. On the other, they were concerned about effects of school closures on their children’s education and, in some cases, on their broader social development.

Over three-quarters of the parents of French secondary school students believed that the activities offered by teachers during the period of school closures had been beneficial to their children (81% of the parents of lower-secondary school students and 75% of the parents of students). They also saw positive effects in terms of increased autonomy of their children (60%) and in the discovery of new methods of learning (60%) (Barhoumi et al., 2020, Figs. 4.5 and 4.6). The amount of work that schools gave to their children was seen as appropriate by nearly two out of three parents of secondary school students, with between 16 and 23% of parents seeing it as being too much and between 12 and 20% as too little (depending on the level) (Barhoumi et al., 2020, Fig. 2.12) At the same time, most were of the view that while their children’s learning had been maintained (66%), it had not progressed (58%) and reported no perceived improvement in their children’s level in certain subjects (63%) (Barhoumi et al., 2020, Fig. 5.7).

In the US, around four in five parents (83%) reported being satisfied with the way their children’s school had been handling instruction during school closure (Horowitz, 2020), and high proportions of parents rated their child(ren)’s school as doing an excellent or good job in terms of teachers availability to answer questions (77%), communication about the distance education programme from the superintendent and/or principal (71%), provision of materials and equipment needed for the child to do schoolwork (75%), and communication about specific assignments from teachers (72%) (Jones, 2020a). Satisfaction with schools was nevertheless accompanied by concern about the impact of home schooling on their children’s educational progress. In late March 2020, 42% of parents of K-12 students were “very” or “moderately” concerned that the pandemic would have a negative impact on their child’s education (Brenan, 2020) and, in a poll conducted in early April 2020, 64% of respondents were concerned about their children falling behind because of the Corona virus outbreak (Horowitz, 2020).

Some 70% of parents in the United Kingdom agreed that children within their household were continuing to learn whilst being schooled from home. At the same time, 43% of the same parents agreed that remote schooling was negatively affecting the well-being of their children, and 42% of parents agreed that their oldest (or only) children were struggling to continue their education remotely (ONS, 2020, Table 4).

In Ireland, in August 2020, only one-third (36%) of parents of secondary school students were worried about their child returning to school because they had fallen behind due to lockdown (CSO 2020, Table 3.6). However, most parents/guardians had a negative impression of the impact of enforced school closures (CSO 2020, Tables 2.1, 2.2, 2.4 and 2.5). Closures were seen as having a major or moderate negative impact on students’ learning by 41% of parents of primary and 46% of parents of secondary students and on their social development (42% and 23% respectively). Few parents/guardians of either primary or secondary students (close to 15% in both cases) viewed the impact of school closures as neutral or positive on either their children’s learning or social development. Irish parents were also rather negative about their child’s school in providing adequate home learning support should schools be closed again, the implication being that they were not particularly happy about the support provided during the closures earlier in the year. Some 38% of parents of primary school students were very or extremely concerned, with only 23% not being concerned at all. Concerns were greatest regarding children in secondary school. The share of parents who were very or extremely concerned about schools’ capacity to support home learning rose to 52% in the case of children enrolled in the junior secondary certificate, and 72% for those enrolled in the leaving certificate.

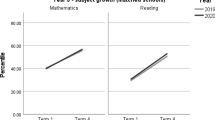

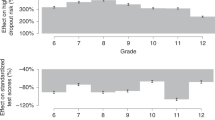

15.5.2 The Performance of Students on Standardised Tests Compared with that of Their Peers in Previous years

The concerns of parents that their children’s learning had not progressed during the period of school closures to the extent that it would have in normal circumstances are echoed by many other commentators. Claims regarding potentially dramatic “lifelong” learning losses and the widening of inequality and long-run economic costs have been made based on simulation studies (see, for example, Azevedo et al., 2020 and Hanushek & Woessman, 2020). Comparisons of the results in standardised tests administered in 2020 following the return of students to school with those in similar tests for students in the same year level in earlier years provide an important source of empirical information regarding the academic progress of pupils during this period. Testing programmes were interrupted due to the pandemic in many countries. However, testing continued in a few others and several comparisons of the performance of students experiencing school closures in 2020 with students in the same year of schooling in 2019 and earlier years have been released. Table 15.8 presents the results of five studies (using data from England, France, Flanders, the Netherlands, and the US).

The most comprehensive and highest quality data concerning the academic progress of the cohort of students affected by school closures comes from France. Results from annual national tests conducted at the start of the school year for students in Years 1, 2, and 6 and in the middle of the year for students in Year 1 have been released for the 2020/21 school year. The tests had very high rates of participation by schools and students in all years covered (including 2020 and 2021). In the other studies, the data come from non-representative samples of schools (England, the Netherlands, the United States) or suffers from low participation by schools in the 2020 testing round (Flanders). In addition, in the countries in which the tests were conducted at the end of the 2020 school year (Flanders, the Netherlands, and the United States), rates of participation by students were low.Footnote 6

Results vary widely. Improvement, as well as stability and decline (both small and large) in the performance of the ‘Covid cohorts’ relative to their peers tested in previous years is observed (Table 15.8). In France, the performance of the cohort of Year 6 students tested at the start of the 2020–21 school year improved relative to their peers tested in 2019 in both French and mathematics, with the improvement being more pronounced in French than in mathematics. The performance of the 2020–21 Year 1 cohort tested in mid-year also improved compared to the 2019–20 cohort in both domains. Interestingly, its performance had fallen relative to students tested in the previous year cohort in the tests conducted at the start of the year, suggesting that, during the first six months of the 2020–21 school year, these pupils had caught up on any instruction that they had missed in March-June 2020. Stability or small declines in performance were found in France (Year 2 in French and mathematics), Flanders (social science) and the United States (reading). Large declines were observed in England (maths and reading), Flanders (Dutch, French, maths, and science), the Netherlands (a composite measure), and the United States (maths).

Evidence regarding the differential impact of the disruptions to education caused by school closures by socio-economic background is also mixed. The French and US studies find little evidence of widening socio-economic gaps in performance between 2020 and previous years. In fact, in France, performance in French improved marginally more for students in Year 6 who attended schools belonging to “priority education networks” that catered for pupils from lower socio-economic backgrounds conditions than for other students. However, in mathematics, students in these “priority education” schools improved to a lesser extent than that of their peers in other schools (Andreu et al., 2020a, p. 37). The studies using Dutch (Engzell, Frey & Verhagen, 2020) and Flemish data (Maldonado and De Witte, 2020) find that the performance decline of the Covid cohorts relative to pre-Covid cohorts is greater among students from lower socio-economic backgrounds. The English study comes to similar conclusions by inference rather than observation (Rose et al., 2021, pp. 10–12), and the evidence is unconvincing.Footnote 7

The difference in the results found in these studies is intriguing and its explanation is beyond the scope of this paper. Apart from issues of sampling and missing data mentioned above, the timing of testing may have some impact. The French assessments were undertaken at the beginning of the 2020–21 school year (September 2020) in conditions far closer to the ‘normal’ conditions that applied in previous testing rounds than was the case for tests conducted in June 2020. In addition, the extent to which the tests evaluate knowledge directly related to the content of the curriculum may differ. For example, the French assessments are primarily diagnostic in focus rather than intended to evaluate what had been learnt in the previous year.

The scale of the effects estimated in the English, Dutch, and Flemish studies deserves some comment. The Flemish study concludes that, on average, the average gain in performance of Year 6 students in 2020 was only half to one-quarter of that expected in a normal year. This effect seems implausibly large. The implication is that the substitution of remote schooling for school-based instruction for a period of seven weeksFootnote 8 (around 20% of yearly instruction time) resulted in a reduction of 50–75% of the normal yearly learning gain. At face value, the Dutch and English results seem more credible, as they suggest that pupils learnt about 80% of what they would be expected to learn in a normal year. However, even here, the inference is that students at best maintained the level of improvement they had achieved when their schools closed—which is surprising given that most students continued some form of school learning from home during the school closures. At the same time, the results that suggest no impact of the disruption to schooling on performance also raise questions. They stand in contrast with the evidence that while most pupils continued with their education, they spent less time, on average, in learning activities than they would have done had the 2019–20 school year continued as normal.

In the end, however, time will be needed before we have a good understanding of the short- and long-term consequences of the period of school closures during the first wave of the pandemic on the achievement and broader development of students. Placing the results for 2020 in the context of longer-term trends is essential for their interpretation, and the next waves of testing programmes will provide vital information. For the moment, considerable caution should be exercised in attributing a causal relationship between the disruption to children’s education due to lockdowns and school closures, and changes to performance for students of the same age at the same stage in their education tested in 2020 and in previous years (not to mention longer time intervals). Many factors can lead to variations in performance between different cohorts at the same point in their schooling: different past experiences, variation in the distribution of demographic and other characteristics in different cohorts, measurement errors (including variation in tests and their administration), and in the case of sample studies, sampling errors. Adjustments can be made to account for some of these factors in analysis, but not for others.

15.6 Summary and Conclusion

The aim of this chapter is to provide the reader with examples of the experience of education during the first months of the Covid-19 pandemic in high-income countries, drawing on data derived from representative samples. The data which meets this condition is restricted to a small number of countries—France, Ireland, the United Kingdom, and the United States—supplemented by information, where available from Australia, the Czech Republic, Flanders, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands. There is also variation in the coverage and treatment of different topics in the different surveys, and often the information collected on similar topics in different surveys is not entirely comparable. This data provides an important, if incomplete, insight into the educational experience of schoolchildren and their families during the school closures and lockdowns of March-June 2020.

15.6.1 The Overall Picture

The closure of schools appears to have led to some students disengaging from their school learning. There is evidence that 10% to 20% of students may have discontinued their school learning in some countries during the “remote learning” period.

In almost all the countries for which information is available, students spent on average about 3 h per (school) day doing schoolwork at home—about half the face-to-face instruction time they would have received at school. Students received assistance from their parents (and from their other family members), but this assistance was fairly limited in duration and scope and decreased as students got older. The most common form of remote schooling in the OECD countries, for which representative information is available, was for teachers to send online resources/exercises to their students—most of the time through online platforms, sometimes also by e-mail, and more rarely as paper worksheets. Teachers also provided virtual instruction and assistance, but to a relatively limited extent.

The time spent on learning during school closures was related to the age of children. Younger children generally spent less time on schoolwork than older children. In part, this reflects the fact that instruction time in normal school settings is less for primary school than secondary students. In addition, schools and teachers may have wished to avoid overburdening young children (and their parents) with schoolwork and focused on facilitating a continuing link with school and the maintenance of study habits, rather than covering all aspects of the normal curriculum. Younger children also received more assistance from their parents, probably because they needed more, being less able than their older counterparts to work autonomously.

Parents offer a rather mixed evaluation of the impact of lockdowns and school closures on children’s development and educational progress. High levels of appreciation of the work of schools and teachers during school closures was accompanied by concerns regarding the effects of lockdowns and school closures on children’s educational and social development. While most children maintained a link with school and there were some positive features of home schooling for children, such as increasing autonomy in learning and the discovery of new methods of learning, many parents were concerned about lack of progress in some subjects and the possibility that their children were falling behind.

The empirical evidence regarding the extent to which school students ‘fell behind’ or failed to make the same gains in achievement as they would have in normal circumstances (“reduced learning gain” is probably a more accurate description than the often used “learning loss”) is restricted to results from a small number of studies of varying quality and generalisability. Both small improvements and large declines in performance between students tested in 2020 and those tested in previous years have been reported. The most robust available study, from France, suggests that it is possible that the differences in achievement between the students affected by closures in 2020 and students at the same level tested in 2019 was negligible (with both small positive and small negative changes being found). At the other end of the scale, large declines in achievement (in some cases implausibly so) were also found in the studies using data from England, Flanders, the Netherlands, and the United States (in mathematics but not reading). However, these studies were based on convenience samples and/or had low rates of participation by schools and students in 2020. At this point, any judgement on this question must remain provisional. More studies using high quality data representative of the student population are needed.

15.6.2 The Equity Picture

A major concern in all countries is the possible differential consequences of school closures, lockdowns, and the pandemic more generally on schoolchildren from different social backgrounds. Given the well-documented inequalities in housing conditions, access to technology and connectivity, in the educational services they get from their schools, as well as on the impact of Covid on parents’ health and employment, concerns about students from lower socio-economic background being left behind are more than reasonable. Those concerns are largely confirmed by the current evidence, but some aspects of those inequities challenge some common expectations.

There is also good reason to believe that students who disengaged from their school learning came disproportionately from lower socio-economic backgrounds, but there is no direct information at this stage. Some factors for which we have information point to that direction. The availability of devices and access to internet connectivity affected more students from lower socio-economic backgrounds than others. There is clear evidence of this in the United States, where poor access to computers and connectivity disproportionately affected households headed by parents who were less educated, earned less income, or were Black or Latino. In addition, in the US, the pandemic disproportionately affected Black and Latino families, who were about twice as likely as White and Asian people to be hospitalised and/or die from Covid, which was likely to have an impact on the remote schooling of their (grand)children (US CDCP, 2021).Footnote 9

In the countries covered, there is no evidence (yet) of family socio-economic status having an impact on the amount of time spent on schoolwork or the amount of time parents spent assisting children: children from all backgrounds seem to have devoted the same time to their schoolwork and have received the same amount of parental assistance. In fact, students from higher socio-economic status families sometimes received less support than those from lower status families. This may reflect the fact that parents in higher-status jobs had less time to support their children as they were more likely to have been working (rather than being on temporary layoff or unemployed) during lockdowns than adults with less education in lower-status occupations. It may be possible that the effectiveness of the assistance offered was dependent of the level of education of parents. Importantly, however, the interest in and willingness to provide support was equally distributed across households from all backgrounds.

15.6.3 In Summary

The picture offered of the experiences and consequences in high-income countries of the period of school closures in this chapter is a relatively optimistic one. The lockdowns and associated closures of schools implemented in response to the arrival of the Covid-19 pandemic represented a sudden and unprecedented event for which school authorities, teachers, parents, and students were unprepared. Nevertheless, distance and remote education arrangements were put in place at short notice in emergency conditions. This allowed education to continue at home for most children, and a form of school-based education to be offered to children with special needs and the children of parents with no other care options, such as the children of ‘essential’ workers. While few would disagree that the distance/remote education arrangements put in place represented a less than perfect substitute for normal classes, they ensured that most, though not all, children continued to have a connection with teachers and their schools. For the most part, teachers, students, and parents adapted to the new arrangements. Most teachers continued to teach, and most students continued to learn. The fears of significant negative effects on student learning appear to not have been realised. While widening educational inequalities remains very plausible, they seem to have been limited in the high-income countries covered. Such a dramatic and sudden disruption to schooling arrangements can hardly be expected to have been without some impact on students’ learning, especially in the context of the arrival of a pandemic and the disruptive effect of lockdowns on every aspect of social and economic life. However, even if definitive conclusions cannot be drawn at this point, it appears likely that the negative consequences have been modest in scale and impact. For most children, missing 8–18 weeks of face-to-face schooling, even in a situation of lockdown, appears unlikely to have had dramatic consequences for either their academic or broader development, or led to the significant widening of pre-existing inequalities.

A few words of caution are necessary, however. The results presented in this chapter relate to a small number of high-income countries that experienced about 2–3 months of school closure during the first wave of the pandemic. The situation was and continues to be very different in middle- and low-income countries, where schools, in some cases, remained closed for long periods and the establishment of effective alternative delivery arrangements has been a considerable challenge. In those countries, socio-economic disparities are more marked and more likely to widen as time out of school increases.

15.6.4 Looking Ahead

Assuming some effects on student’s learning, an important question is whether students affected will be able to ‘catch up’ on or consolidate any gaps in their learning resulting from the disruption to their schooling during the period of school closures. The scale of any on-going impact of the disruption to students’ education caused by school closures on their academic performance and progress will be related to, among other things, (1) the relevance of what has been missed for their subsequent educational progress, (2) the opportunities they have and support they are given to catch-up on any learning ‘gaps’ resulting from reduced instruction and learning during school closures, and (3) the evolution of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Regarding the former, for many students failing to cover some elements of the curriculum in some subjects may not matter for their subsequent progress (or, a fortiori, for their “human capital” when they enter the labour market). By no means all the content covered in a subject in one year is a necessary pre-requisite for subsequent progress in either the subject area directly concerned or related areas.

In terms of the opportunities for catch-up, consolidation of the gaps in students’ education due to the disruption flowing from school closures was high on the agendas of most governments and school authorities at the start of the 2020–21 school year. OECD (2021, Table 3.3) reports that around three-quarters of the countries for which data is available implemented ‘remedial measures to reduce learning gaps’ when schools reopened after the first period of closures.Footnote 10 In France for example, the priorities for the new school year included support for students to consolidate the aspects of their programmes that they did not cover due to confinement.Footnote 11 In the UK, the government introduced a Coronavirus catch-up premium and a national tutoring programme to support students and young people affected by the disruption of their education.Footnote 12 Even in the absence of specific programmes, it is likely that teachers will adjust their instruction to compensate for what was missed by students. Many parents will make efforts to ensure that their children catch up, as may the students themselves (especially those in senior high school). This is likely to be true regardless of their socio-economic status (although their effectiveness in reaching their goals may vary).

The evolution of the Covid-19 pandemic represents something of a wild card. At the start of 2021, the school closures of March-June/July 2020 can be seen as the first phase of a period of on-going disruption to school education that appears set to continue until the middle of 2021. Schools reopened in most high-income countries towards the end of the 2019–20 school year, at the start of the 2020–21 year in the northern hemisphere or mid-year in the southern hemisphere. An exception is the Americas, where schools have remained either closed in some countries or opened unevenly due to the decentralised nature of the education governance. However, even where schools reopened, children’s education continued to be affected by the implementation of strict sanitary protocols, the closure of classes and individual schools due to cases of Covid-19 among students and staff, and the introduction of ‘hybrid’ forms of schooling alternating face-to-face and on-line delivery of lessons, as well as further episodes of school closures at regional or national level in some countries. This continuing disruption has the potential not only to complicate the consolidation of previous learning gaps, but also lead to additional learning gaps. Given the relatively low level of continuing disruption in most countries, and the fact that school systems will have learnt from the experience of the spring 2020 school closures (see e.g., NSW Department of Education, 2020), it can be hoped that the consolidation of learning will not be overly affected. However, the possibility that the evolution of the Covid-19 pandemic has more surprises in store cannot be ruled out.

This leads to the issue of data and the long-term monitoring of the consequences of the pandemic (not only the period of school closures in spring 2020) on children’s schooling. Surprisingly, few high-quality data collections were put in place during the period of school closures. This has restricted the capacity of researchers and others to have a good understanding of what occurred during this period, and of the behaviour and views of those involved and affected by closures and the disruption to school education. In this respect, it is important that school systems and Ministries of Education make publicly available as much of the administrative and other data regarding this period as they can, as well as facilitate access to relevant documentation about policies and administrative decisions. Access to data from standardised tests is particularly important, not only from those that took place in 2020 and earlier years but, equally importantly, those that will take place over the coming years.

Notes

- 1.

Where less severe ‘lockdown’ measures regarding restrictions on business activities were implemented than many other countries.

- 2.

In the US Household Pulse, around 5% of parents/guardians in the US reported that their child was ‘already homeschooled’ in waves 1–6 (US Census Bureau, 2020, Education Table 1).

- 3.

For example, the proportion of Black households (48%) in which children had some or all their classes cancelled (and not moved to other fomats) was 10 percentage points higher than that of White households (38%).

- 4.

OECD (2021, Fig. 2.2) reports that over 80% of the countries providing data indicated that they offered support to “populations at risk of exclusion from distance education platforms” in the form of “subsidised devices for access (PCs or/and tablets)” during the first period of school closures. However, no information is available on what proportion of pupils had access to such support.

- 5.

The estimate is based on small numbers, however, and is associated with a large margin of error.

- 6.

The effects of selection biases and non-response on the representativeness of the results are argued to be negligible by the authors of all the studies concerned.

- 7.

The 2017 comparison sample “does not provide data on the performance of disadvantaged and nondisadvantaged pupils” (Rose et al., 2021, p. 10). The authors, instead, compare the standardised achievement gap observed among the 2020 sample with that derived from another assessment carried out in 2019 to estimate whether the gap has grown.

- 8.

Nine weeks of the normal school year including two weeks of holidays over Easter.

- 9.

According to the (governmental) US Center for Disease Control and Preventions, as of February 18, 2021, compared to White non-Hispanic persons, Black or African American and Hispanics or Latinos were 2.9 and 3.2-fold more likely to be hospitalised, respectively, and 1.9 and 2.3 more likely to die from Covid-19, respectively. Black or African American and Hispanics or Latinos were 1.1 and 1.3-fold more likely to get the virus. (American Indian or Alaska Natives are those who were the most likely to get the virus, get hospitalised, and die.) Risk for Covid-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death by Race/Ethnicity | CDC.

- 10.

See also UNESCO, UNICEF, and the World Bank (2020, p. 19).

- 11.

As an example: « Au lycée, la rentrée 2020 se place sous le signe de l’identification des besoins propres à chaque élève et des réponses personnalisées qui peuvent y être apportées, avec pour objectif de résorber les écarts qui ont pu naître pendant la crise sanitaire». (“In senior high schools, the start of the 2020 school year has as its focus the identification of the individual needs of each student and the personalised support that can be offered to overcome the gaps in learning that may have developped during the health crisis”). https://eduscol.education.fr/cid152895/rentree-2020-priorites-et-positionnement.html.

- 12.

References

Andreu, S., et al. (2020a). Évaluations de début de sixième 2020 : Premiers résultats, document de travail, novembre 2020, Série Études, Document de travail no 2020-E05, Novembre 2020.

Andreu, S., et al. (2020b). Evaluations 2020 Repères CP, CE1 : premiers résultats, Série Études, Document de travail no 2020-E04, Novembre 2020.

Andreu, S., et al. (2021). Evaluations 2021 Point d’étape CP : premiers résultats, Série Études, Document de travail no 2021-E07, Mars 2021.

Assemblée Nationale. (2019). Question n°15996. https://questions.assemblee-nationale.fr/q15/15-15996QE.htm. Question n°15996: Assemblée nationale (assemblee-nationale.fr)

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2020). Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey, 12–15 May 2020, Australia. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/household-impacts-covid-19-survey/12-15-may-2020

Azevedo, P., Hasan, A., Geven, K., Goldemberg, D., & Iqbal, S. A. (2020). Learning losses due to COVID-19 could add up to $10 trillion, Brookings Institute, Future Development, Thursday, July 30, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2020/07/30/learning-losses-due-to-covid-19-could-add-up-to-10-trillion/

Barhoumi, M., et al. (2020). Continuité pédagogique—période de mars à mai 2020—enquêtes de la DEPP auprès des familles et des personnels de l’Éducation nationale—premiers résultats, document de travail n°2020-E03—Juillet 2020, Ministère de l’Éducation nationale, de la Jeunesse et des Sports, Direction de l’évaluation, de la prospective et de la performance.

Benzeval, M., Borkowska, M., Burton, J., Crossley, T. F., Fumagalli, L., Jäckle, A., Rabe, B., & Read, B. (2020). Understanding Society COVID-19 Survey April Briefing Note: Home schooling, Understanding Society Working Paper No 12/2020, ISER, University of Essex, https://www.understandingsociety.ac.uk/research/publications/526136

Brenan, M. (2020). 42% of Parents Worry COVID-19 Will Affect Child’s Education, Gallup Panel, March 24–29, 2020, https://news.gallup.com/poll/305819/parents-worry-covid-affect-child-education.aspx

Central Statistical Office (Ireland) (CSO). (2020). Social Impact of COVID-19 Survey: The Reopening of Schools, August 2020, https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-sic19ros/socialimpactofcovid-19surveyaugust2020thereopeningofschools/

Chapman, S. (2020). Australia Homeschooling Trends Over the Last Decade, Home School Legal Defense Association, https://hslda.org/post/australia-homeschooling-trends-over-the-last-decade

Czech School Inspectorate (CSI). (2020). Distance learning in basic and upper secondary schools in the Czech Republic, Česká školní inspekce, https://www.oecd.org/education/Czech-republic-distance-learning-in-secondary-schools.pdf

Eivers, E., Worth, J., & Ghosh, A. (2020), Home learning during Covid-19: Findings from the Understanding Society Longitudinal Study, NFER, https://www.nfer.ac.uk/media/4101/home_learning_during_covid_19_findings_from_the_understanding_society_longitudinal_study.pdf

Engzell, P., Frey, A., & Verhagen, M. D. (2020), Learning inequality during the Covid-19 pandemic. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/ve4z7

Forsa. (2020). Das Deutsche Schulbarometer Spezial Corona-Krise: Ergebnisse einer Befragung von Lehrerinnen und Lehrern an allgemeinbildenden Schulen im Auftrag der Robert Bosch Stiftung in Kooperation mit der ZEIT, Lehrer-Umfrage—Erstmals repräsentative Daten zum Fernunterricht. Das Deutsche Schulportal (deutsches-schulportal.de).

Gov.ie. (2019). gov.ie. Education www.gov.ie

Gov.uk. (2020). Attendance in education and early years settings during the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak, https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/attendance-in-education-and-early-years-settings-during-the-coronavirus-covid-19-outbreak/2020-week-33

Hamilton, L. S., Kaufman, J. H. & Diliberti, M. K. (2020). Teaching and leading through a pandemic: Key findings from the American educator panels Spring 2020 COVID-19 surveys. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License, 2020, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA168-2.html

Hamilton, L.S., Grant, D., Kaufman, J.H, Diliberti, M.K., Schwartz, H.L., Hunter, G.P., Messan Setodji, C., & Young, C.J. (2020), COVID-19 and the state of K–12 schools: Results and technical documentation from the Spring 2020 American educator panels COVID-19 surveys. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License, 2020, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA168-1.html

Hanushek, E., & Woessman, L. (2020). The economic impacts of learning losses. Education Working Papers, No. 225. OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/21908d74-e

Horowitz, J. M. (2020). Lower-income parents most concerned about their children falling behind amid COVID-19 school closures, Fact Tank April 15, 2020, Pew Reseach Centre. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/04/15/lower-income-parents-most-concerned-about-their-children-falling-behind-amid-covid-19-school-closures/

Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (Istat). (2020). Fase 1: Le Giornate in Casa Durante il Lockdown: 5 – 21 Aprile 2020, Statistiche Report, 5 Giugno, 2020, https://www.istat.it/it/files/2020/06/Giornate_in_casa_durante_lockdown.pdf

Jones, J. M. (2020a). Social Factors Most Challenging in COVID-19 Distance Learning, Gallup Panel, May 11–24, 2020, https://news.gallup.com/poll/312566/social-factors-challenging-covid-distance-learning.aspx

Jones, J. M. (2020b). Amid School Closures, Children Feeling Happiness, Boredom, Gallup Panel, May 25–June 8, 2020, https://news.gallup.com/poll/306140/amid-school-closures-children-feeling-happiness-boredom.aspx

Kuhfeld, M., Ruzek, E., Johnson, A., Tarasawa, B., & Lewis, K. (2020), Technical appendix for: Learning during COVID-19: Initial findings on students’ reading and math achievement and growth, NWEA, https://www.nwea.org/content/uploads/2020/11/Technical-brief-Technical-appendix-for-Learning-during-COVID-19-Initial-findings-on-students-reading-and-math-achievement-and-growth-NOV2020.pdf

Maldonado, J., & De Witte, K. (2020). The effect of school closures on standardised student test, FEB Research Report Department of Economics. https://limo.libis.be/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=LIRIAS3189074&context=L&vid=Lirias&search_scope=Lirias&tab=default_tab&lang=en_US&fromSitemap=1

Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale de la Jeunesse et des Sports. (2021). Programmes et horaires à l’école élémentairehttps://www.education.gouv.fr/programmes-et-horaires-l-ecole-elementaire-9011

NCES. (no date). State Education Reforms website, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/statereform/tab5_14.asp

NHS Digital. (2020). Mental Health of Children and Young People in England, 2020: Wave 1 follow up to the 2017 survey, Excel Tables, https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-of-children-and-young-people-in-england/2020-wave-1-follow-up/data-sets

NSW Department of Education. (2020). Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic January–July 2020. https://www.education.nsw.gov.au/content/dam/main-education/en/home/covid-19/lessons-from-the-covid-19-pandemic-jan-july-2020.pdf

OECD. (2021). The state of school education: One year into the COVID pandemic. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/201dde84-en

Office of National Statistics (ONS). (2020). Coronavirus and homeschooling in Great Britain: April to June 2020 Opinions and Lifestyle Survey (Covid-19 module), 3 April and 10 May 2020 and 7 May to 7 June 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/educationandchildcare/articles/coronavirusandhomeschoolingingreatbritain/apriltojune2020/relateddata

Office of the Schools Adjudicator. (2020). Office of the Schools Adjudicator Annual Report, September 2018 to August 2019, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/872007/OSA_Annual_Report_Sept_2018_to_Aug_2019_corrected.pdf

Pensiero, N., Kelly, A., & Bokhove, C. (2020). Learning inequalities during the Covid-19 pandemic: How families cope with home-schooling. University of Southampton Research Report. https://doi.org/10.5258/SOTON/P0025

Rose, S., Twist, l., Lord, P., Rutt, S., Badr, K., Hope, C., & Styles, B. (2021), Impact of school closures and subsequent support strategies on attainment and socio-emotional wellbeing in Key Stage 1: Interim Paper 1, January 2021, NFER, https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/public/files/Publications/Covid-19_Resources/Impact_of_school_closures_KS1_interim_findings_paper_-_Jan_2021.pdf

Stelitano, L., Doan, S., Woo, A., Diliberti, M.K., Kaufman, J. H., & Henry, D. (2020). The Digital Divide and COVID-19: Teachers’ Perceptions of Inequities in Students’ Internet Access and Participation in Remote Learning. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA134-3.html.

Snyder, T.D., de Brey, C., & Dillow, S.A. (2019). Digest of Education Statistics 2018 (NCES 2020–009), National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, Washington, D.C., https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2020/2020009.pdf

UNESCO, UNICEF, and the World Bank. (2020). What have we learnt? Overview of findings from a survey of ministries of education on national responses to COVID-19. Paris, New York, Washington D.C.: UNESCO, UNICEF, World Bank, http://tcg.uis.unesco.org/survey-education-covid-school-closures/

United States Census Bureau. (2020). Household Pulse Survey: Measuring Social and Economic Impacts during the Coronavirus Pandemic, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey.html

United States Center for Disease Control and Preventions. (2021). Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death By Race/Ethnicity, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html

Vogels, E. (2020). 59% of U.S. parents with lower incomes say their child may face digital obstacles in schoolwork, Pew Research Center, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/09/10/59-of-u-s-parents-with-lower-incomes-say-their-child-may-face-digital-obstacles-in-schoolwork/

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Thorn, W., Vincent-Lancrin, S. (2022). Education in the Time of COVID-19 in France, Ireland, the United Kingdom and the United States: the Nature and Impact of Remote Learning. In: Reimers, F.M. (eds) Primary and Secondary Education During Covid-19. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81500-4_15

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81500-4_15

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-81499-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-81500-4

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)