Abstract

This introductory chapter sets the stage for the book, explaining the goals, methods, and significance of the comparative study. The chapter situates the theoretical significance of the study with respect to research on education and inequality, and argues that the rare, rapid, and massive change in the social context of schools caused by the pandemic provides a singular opportunity to study the relative autonomy of educational institutions from larger social structures implicated in the reproduction of inequality. The chapter provides a conceptual educational model to examine the impact of COVID-19 on educational opportunity. The chapter describes the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic and how it resulted into school closures and in the rapid deployment of strategies of remote education. It examines available evidence on the duration of school closures, the implementation of remote education strategies, and known results in student access, engagement, learning, and well-being.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1.1 Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic shocked education systems in most countries around the world, constraining educational opportunities for many students at all levels and in most countries, especially for poor students, those otherwise marginalized, and for students with disabilities. This impact resulted from the direct health toll of the pandemic and from indirect ripple effects such as diminished family income, food insecurity, increased domestic violence, and other community and societal effects. The disruptions caused by the pandemic affected more than 1.7 billion learners, including 99% of students in low and lower-middle income countries (OECD, 2020c; United Nations, 2020, p. 2).

While just around 2% of the world population (168 million people as of May 27, 2021) had been infected a year after the coronavirus was first detected in Wuhan, China, and only 2% of those infected (3.5 million) had lost their lives to the virus (World Health Organization, 2021a), considerably more people were impacted by the policy responses put in place to contain the spread of the virus. Beyond the infections and fatalities reported as directly caused by COVID-19, analysis of the excess mortality since the pandemic outbreak, suggests that an additional 3 million people may have lost their lives to date because of the virus (WHO, 2021b).

As the General Director of the World Health Organization declared the outbreak of COVID-19 a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) on January 30, 2020 (WHO, 2020a), countries began to adopt a range of policy responses to contain the spread of the virus. The adoption of containment practices accelerated as the COVID-19 outbreak was declared a global pandemic on March 11, 2020 (WHO, 2020b).

Chief among those policy responses were the social distancing measures which reduced the ability of many people to work, closed businesses, and reduced the ability to congregate and meet for a variety of purposes, including teaching and learning. The interruption of in-person instruction in schools and universities limited opportunities for students to learn, causing disengagement from schools and, in some cases, school dropouts. While most schools put in place alternative ways to continue schooling during the period when in-person instruction was not feasible, those arrangements varied in their effectiveness, and reached students in different social circumstances with varied degrees of success.

In addition to the learning loss and disengagement with learning caused by the interruption of in-person instruction and by the variable efficacy of alternative forms of education, other direct and indirect impacts of the pandemic diminished the ability of families to support children and youth in their education. For students, as well as for teachers and school staff, these included the economic shocks experienced by families, in some cases leading to food insecurity, and in many more causing stress and anxiety and impacting mental health. Opportunity to learn was also diminished by the shocks and trauma experienced by those with a close relative infected by the virus, and by the constraints on learning resulting from students having to learn at home, and from teachers having to teach from home, where the demands of schoolwork had to be negotiated with other family necessities, often sharing limited space and, for those fortunate to have it, access to connectivity and digital devices. Furthermore, the prolonged stress caused by the uncertainty over the evolution and conclusion of the pandemic and resulting from the knowledge that anyone could be infected and potentially lose their lives, created a traumatic context for many that undermined the necessary focus and dedication to schoolwork. These individual effects were reinforced by community effects, particularly for students and teachers living in communities where the multifaceted negative impacts resulting from the pandemic were pervasive.

Beyond these individual and community effects of the pandemic on students, and on teachers and school staff, the pandemic also impacted education systems and schools. Burdened with multiple new demands for which they were unprepared, and in many cases inadequately resourced, the capacity of education leaders and administrators, who were also experiencing the previously described stressors faced by students and teachers, was stretched considerably. Inevitably, the institutional bandwidth to attend to the routine operations and support of schools was diminished and, as a result, the ability to manage and sustain education programs was hampered. Routine administrative efforts to support school operations as well as initiatives to improve them were affected, often setting these efforts back.

Published efforts to take stock of the educational impact of the pandemic to date, as it continues to unfold, have largely consisted of collecting and analyzing a limited number of indicators such as enrollment, school closures, or reports from various groups about the alternative arrangements put in place to sustain educational opportunity, including whether, when, and how schools were open for in-person instruction and what alternative arrangements were made to sustain education remotely. Often these data have been collected in samples of convenience, non-representative, further limiting the ability to obtain true estimates of the education impact of the pandemic on the student population. A recent review of research on learning loss during the pandemic identified only eight studies, all focusing on OECD countries which experienced relatively short periods of school closures (Belgium, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Spain, the United States, Australia, and Germany). These studies confirm learning loss in most cases and, in some, increases in educational inequality, but they also document heterogeneous effects of closures on learning for various school subjects and education levels (Donelly & Patrinos, 2021).

There have also been predictions of the likely impact of the pandemic, consisting mostly of forecasts and simulations based on extrapolations of what is known about the interruption of instruction in other contexts and periods. For example, based on an analysis of the educational impact of the Ebola outbreaks, Hallgarten identified the following likely drivers of school dropouts during COVID-19: (1) the reduction in the availability of education services, (2) the reduction in access to education services, (3) the reduction in the utilization of schools, and (4) lack of quality education. Undergirding these drivers of dropout are these factors: (a) school closures, (b) lack of at-home educational materials, (c) fear of school return and emotional stress caused by the pandemic, (d) new financial hardships leading to difficulties paying fees, or to children taking up employment, (e) lack of reliable information on the evolution of the pandemic and on school reopenings, and (f) lack of teacher training during crisis. (Hallgarten, 2020, p. 3).

Another type of estimate of the likely educational cost of the pandemic includes forecasts of the future economic costs for individuals and for society. A simulation of the impact of a full year of learning loss estimated it as a 7.7% decline in discounted GDP (Hanushek & Woessman, 2020). The World Bank estimated the cost of the education disruption as a $10 trillion dollars in lost earnings over time for the current generation of students (World Bank, 2020).

Many of the reports to date of the educational responses to the pandemic and their results are in fact reports of intended policy responses, often reflecting the views of the highest education authorities in a country, a view somewhat removed from the day-to-day realities of teachers and students and that provides information about policy intent rather than on the implementation and actual effect of those policies. For instance, the Inter-American Development Bank conducted a survey of the strategies for education continuity adopted by 25 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean during the first phase of the crisis, concluding that most had relied on the provision of digital content on web-based portals, along with the use of TV, radio, and printed materials, and that very few had integrated learning management systems, and only one country had kept schools open (Alvarez et al., 2020).

These reports, valuable as they are, are limited in what they contribute to understanding the ways in which education systems, teachers, and students were impacted by the pandemic and about how they responded, chiefly because it is challenging to document the impact of an unexpected education emergency in real time, and because it will take time to be able to ascertain the full short- and medium-term impact of this global education shock.

1.2 Goals and Significance of this Study

This book is a comparative effort to discern the short-term educational impact of the pandemic in a selected number of countries, reflecting varied levels of financial and institutional education resources, a variety of governance structures, varied levels of education performance, varied regions of the world, and countries of diverse levels of economic development, income per capita, and social and economic inequality. Our goal is to contribute an evidence-based understanding of the short-term educational impact of the pandemic on students, teachers, and systems in those countries, and to discuss the likely immediate effects of such an impact. Drawing on thirteen national case studies, a chapter presenting a comparative perspective in five OECD countries and another offering a global comparative perspective, we examine how the pandemic impacted education systems and educational opportunity for students. Such systematic stock-taking of how the pandemic impacted education is important for several reasons. The first is that an understanding of the full global educational impact of the pandemic necessitates an understanding of the ways in which varied education systems responded (such as the nature and duration of school closures, alternative means of education delivery deployed, and the goals of those strategies of education continuity during the pandemic) and of the short-term results of those responses (in terms of school attendance, engagement, learning and well-being for different groups of students). In order to understand the possible student losses in knowledge and skills, or in educational attainment that the current cohort of students will experience relative to previous or future cohorts, and to understand the consequences of such losses, we must first understand the processes through which the pandemic influenced their opportunities to learn. Such systematization and stock-taking are also essential to plan for remediation and recovery, in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic and beyond. While the selection of countries was not intended to represent the entire world, the knowledge gained from the analysis of the educational impact of the pandemic on these diverse cases, as well as making visible what is not yet known, will likely have heuristic value to educators designing mitigation and remediation strategies in a wide variety of settings and may provide a useful framework to design further research on this topic.

In addition, the pandemic is likely to exacerbate preexisting challenges and to create new ones, increasing unemployment for instance or contributing to social fragmentation, which require education responses. Furthermore, there were numerous education challenges predating the pandemic that need attention. Addressing these new education imperatives, as well as tackling preexisting ones, requires ‘building back better’; not just restoring education systems to their pre-pandemic levels of functioning, but rather realigning them to these new challenges. Examining the short-term education response to the pandemic provides insight into whether the directionality of such change is aligned to ‘building back better’ and with the kind of priorities that should guide those efforts during the remainder of the pandemic and in the pandemic aftermath.

Lastly, the pandemic provides a rare opportunity to help us understand how education institutions relate to other institutions and to their external environment under conditions of rapid change. Much of what we know about the relationship of schools to their external environment is based on research carried out in much more stable contexts, where it is difficult to discern what is a cause and what is an effect. For instance, there is robust evidence that schools often reflect and contribute to reproducing social stratification, providing children from different social origins differential opportunities to learn, and resulting in children of poor parents receiving less and lower quality schooling than children of more affluent parents. It is also the case that educational attainment is a robust predictor of income. Increases in income inequality correlate with increases in education inequality, although government education policies have been shown to mitigate such a relationship (Mayer, 2010).

The idea that education policy can mitigate the structural relationship between education and income inequality suggests that the education system has certain autonomy from the larger social structure. But disentangling to what extent school policy and schools can just reproduce social structures or whether they can transform social relations is difficult because changes in education inequality and social inequality happen concurrently and slowly, which makes it difficult to establish what is cause and what is effect. However, a pandemic is a rare rapid shock to that external environment, the equivalent of a solar eclipse, and thus a singular opportunity to observe how schools and education systems respond when their external environment changes, quite literally, overnight. Such a shock will predictably have disproportionate impacts on the poor, via income and health effects, presenting a unique opportunity to examine whether education policies are enacted to mitigate the resulting disproportionate losses on educational opportunity from such income and health shocks for the poor and to what extent they are effective.

1.3 A Stylized Global Summary of the Facts

A full understanding of the educational impact of the pandemic on systems, educators, and students will require an analysis of such impact in three time frames: the immediate impact, taking place while the pandemic is ongoing; the immediate aftermath, as the epidemic comes under control, largely as a result of the population having achieved herd immunity after the majority has been inoculated; and the medium term aftermath, once education systems, societies, and economies return to some stability. Countries will differ in the timeline at which they transition through these three stages, as a function of the progression of the pandemic and success controlling it, as a result of public health measures and availability, distribution, and uptake of vaccines, and as a result of the possible emergence of new more virulent strands of the virus which could slow down the efforts to contain the spread. There are challenges involved in scaling up the production and distribution of vaccines, which result in considerable inequalities in vaccination rates among countries of different income levels. It is estimated that 11 billion doses of vaccines are required to achieve global herd immunity (over 70% of the population vaccinated). By May 24, 2021, a total of 1,545,967,545 vaccine doses had been administered (WHO, 2021a), but 75% of those vaccines have been distributed in only 10 high income countries (WHO, 2021c).

Of the 9.5 billion doses expected to be available by the end of 2021, 6 billion doses have already been purchased by high and upper middle-income countries, whereas low- and lower-income countries—where 80% of the world population lives—have only secured 2.6 billion, including the pledges to COVAX, an international development initiative to vaccinate 20% of the world population (Irwin, 2021). At this rate, it is estimated that it will take at least until the end of 2022 to vaccinate the lowest income population in the world (Irwin, 2021).

The educational impact of the pandemic in each of these timeframes will likely differ, as will the challenges that educators and administrators face in each case, with the result that the necessary policy responses will be different in each case. The immediate horizon—what could be described as the period of emergency—can in turn be further analyzed in various stages since, given the relatively long duration of the pandemic, spanning over a year, schools and systems were able to evolve their responses in tandem with the evolution of the epidemic and continued to educate to varying degrees as a result of various educational strategies of education continuity adopted during the pandemic. During the initial phase of this immediate impact, the responses were reactive, with very limited information on their success, and with considerable constraints in resources available to respond effectively. This initial phase of the emergency was then followed by more deliberate efforts to continue to educate, in some cases reopening schools—completely or in part—and by more coordinated and comprehensive actions to provide learning opportunities remotely. The majority of the analysis presented in this book focuses on this immediate horizon, spanning the twelve months between January of 2020, when the pandemic was beginning to extend beyond China, as the global outbreak was recognized on March 11, through December of 2020.

The pandemic’s impact in the immediate aftermath and beyond will not be a focus of this book, largely because most countries in the world have not yet reached a post-pandemic stage, although the concluding chapter draws out implications from the short-term impact and responses for that aftermath.

Education policy responses need to differentially address each of these three timeframes: short-term mitigation of the impact during the emergency; immediate remediation and recovery in the immediate aftermath; and medium-term recovery and improvement after the initial aftermath of the pandemic.

As the epidemic spread from Wuhan, China—where it first broke out in December of 2019—throughout the world, local and national governments suspended the operation of schools as a way to contain the rapid spread of the virus. Limiting gatherings in schools, where close proximity would rapidly spread respiratory infections, had been done in previous pandemics as a way to prevent excess demand for critical emergency services in hospitals. Some evidence studying past epidemics suggested in fact that closing schools contributed to slow down the spread of infections. A study of non-pharmaceutical interventions adopted during the 1918–19 pandemic in the United States shows that mortality was lower in cities that closed down schools and banned public gatherings (Markel et al., 2007). A review of 79 epidemiological studies, examining the effect of school closures on the spread of influenza and pandemics, found that school closures contributed to contain the spread (Jackson et al., 2013).

In January 26, China was the first country to implement a national lockdown of schools and universities, extending the Spring Festival. As UNESCO released the first global report on the educational impact of the pandemic on March 3, 2020, twenty-two countries had closed schools and universities as part of the measures to contain the spread of the virus, impacting 290 million students (UNESCO, 2020). Following the World Health Organization announcement, on March 11, 2020, that COVID-19 was a global pandemic, the number of countries closing schools increased rapidly. In the following days 79 countries had closed down schools (UNESCO, 2020).

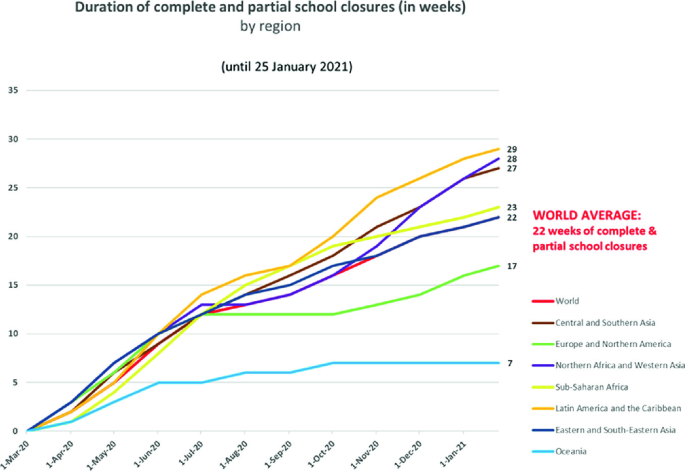

Following the initial complete closure of schools in most countries around the world there was a partial reopening of schools, in some cases combined with localized closings. By the end of January 2021, UNESCO estimated that globally, schools had completely closed an average of 14 weeks, with the duration of school closures extending to 22 weeks if localized closings were included (UNESCO, 2021). There is great variation across regions in the duration of school closures, ranging from 20 weeks of complete national closings in Latin America and the Caribbean to just one month in Oceania, and 10 weeks in Europe. There is similar variation with respect to localized closures, from 29 weeks in Latin America and the Caribbean to 7 weeks in Oceania, as seen in Fig. 1.1. By January 2021, schools were fully open in 101 countries.

Source UNESCO (2021)

Duration of complete and partial school closures by region by January 25, 2021.

As it became clear that it would take considerable time until a vaccine to prevent infections would become available, governments began to consider options to continue to educate in the interim. These options ranged from total or partial reopening of schools to creating alternative means of delivery, via online instruction, distributing learning packages, deploying radio and television, and using mobile phones for one- or two-way communication with students. In most cases, deploying these alternative means of education was a process of learning by doing, sometimes improvisation, with a rapid exchange of ideas across contexts about what was working well and about much that was not working as intended. As previous experience implementing these measures in a similar context of school lockdown was limited, there was not much systematized knowledge about what ‘worked’ to transfer any approach with some confidence of what results it would produce in the context created by the pandemic. As these alternatives were put in place, educators and governments learned more about what needs they addressed, and about which ones they did not.

For instance, it soon became apparent that the creation of alternative ways to deliver instruction was only a part of the challenge. Since in many jurisdictions schools deliver a range of services—from food to counseling services—in addition to instruction, it became necessary to find alternative ways to deliver those services as well, not just to meet recognized needs prior to the pandemic but because the emergency was increasing poverty, food insecurity, and mental health challenges, making such support services even more essential.

As governments realized that the alternative arrangements to deliver education had diminished the capacity to achieve the instructional goals of a regular academic year, it became necessary to reprioritize the focus of instruction.

In a study conducted at the end of April and beginning of May 2020, based on a survey administered to a haphazard sample of teachers and education administrators in 59 countries, we found that while schools had been closed in all cases, plans for education continuity had been implemented in all countries we had surveyed. Those plans involved using existing online resources, online instruction delivered by students’ regular teachers, instructional packages with printed resources, and educational television programmes. The survey revealed severe disparities in access to connectivity, devices, and the skills to use them among children from different socio-economic backgrounds. On balance, however, the strategies for educational continuity were rated favourably by teachers and administrators, who believed they had provided effective opportunities for student learning. These strategies prioritized academic learning and provided support for teachers, whereas they gave less priority to the emotional and social development of students.

These strategies deployed varied mechanisms to support teachers, primarily by providing them access to resources, peer networks within the school and across schools, and timely guidance from leadership. A variety of resources were used to support teacher professional development, mostly relying on online learning platforms, tools that enabled teachers to communicate with other teachers, and virtual classrooms (Reimers & Schleicher, 2020).

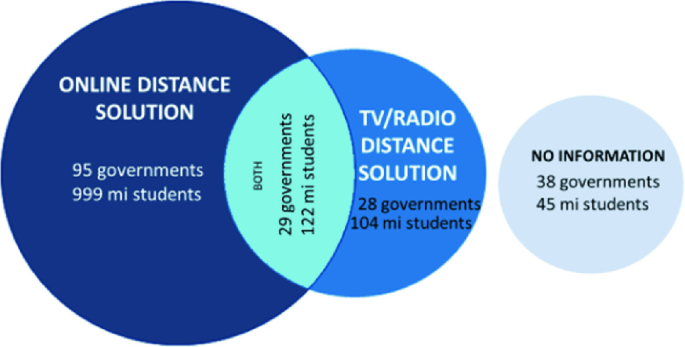

Some countries relied more heavily on some of these approaches, while others used a combination, as reported by UNESCO and seen in Fig. 1.2.

Source Giannini (2020)

Government-initiated distance learning solutions and intended reach.

Source Giannini (2020)

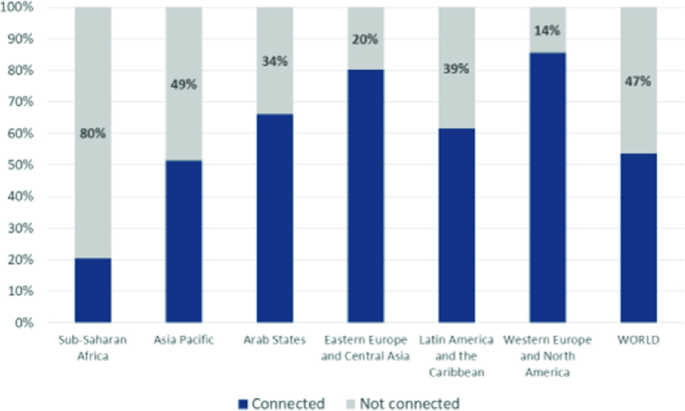

Share of students with Internet at home in countries relying exclusively on online learning platforms.

A significant number of children did not have access to the online solutions provided because of lack of connectivity, as shown in a May 2020 report by UNESCO. In Sub-Saharan Africa, a full 80% of children lacked internet at home; this figure was 49% in Asia Pacific; 34% in the Arab States and 39% in Latin America, but it was only 20% in Eastern Europe and Central Asia and 14% in Western Europe and North America (Giannini, 2020).

Similar results were obtained by a subsequent cross-national study administered to senior education planning officials in ministries of education, conducted by UNESCO, UNICEF, and the World Bank. These organizations administered two surveys between May and June 2020, and between July and October 2020, to government officials in 118 and 149 countries, respectively. The study documented extended periods of school closures. The study further documented differences among countries in whether student learning was monitored, with much greater levels of monitoring in high income countries than in lower income countries.

The study also confirmed that most governments created alternative education delivery systems during the period when schools were closed, through a variety of modalities including online platforms, television, radio, and paper-based instructional packages. Governments also adopted targeted measures to support access to these platforms for disadvantaged students, provided devices or subsidized connectivity, and supported teachers and caregivers. The report shows disparities between countries at different income levels, with most high-income countries providing such support and a third of lower income countries not providing any specific support for connectivity to low-income families (UNESCO-UNICEF-the World Bank, 2020).

The UNESCO-UNICEF-World Bank surveys reveal considerable differences in the education responses by level of income of the country. For instance, whereas by the end of September of 2020 schools in high-income countries had been closed 27 days, on average, that figure increased to 40 days in middle-income countries, to 68 days in lower middle-income countries, and to 60 days in low-income countries (Ibid, 15).

For most countries there were no plans to systematically assess levels of students’ knowledge and skills as schools reopened, and national systematic assessments were suspended in most countries. There was considerable variation across countries, and within countries, in terms of when schools reopened and how they did so. Whereas some countries offered both in-person and remote learning options—and gave students a choice of which approach to use—others did not offer choices. There were also variations in the amount of in-person instruction students had access to once schools reopened. Some schools and countries introduced measures to remediate learning loss as schools reopened, but not all did.

1.4 The Backdrop to the Pandemic: Enormous and Growing Inequality and Social Exclusion

The pandemic impacted education systems as they faced two serious interrelated preexisting challenges: educational inequality and insufficient relevance. A considerable growth in economic inequality, especially among individuals within the same nations, has resulted in challenges of social inclusion and legitimacy of the social contract, particularly in democratic societies. Over the last thirty years, income inequality has increased in countries such as China, India, and most developed countries. Over the last 25 years there are also considerable inequalities between nations, even though those have diminished over the last 25 years. The average income of a person in North America is 16 times greater than the income of the average person in Sub-Saharan Africa. 71% of the world’s population live in countries where inequality has grown (UN, 2021). The Great Recession of 2008–2009 worsened this inequality (Smeedling, 2012).

One of the correlates of income inequality is educational inequality. Studies show that educational expansion (increasing average years of schooling attainment and reducing inequality of schooling) relates to a reduction in income inequality (Coadi & Dizioly, 2017). But education systems, more often than not, reflect social inequalities, as they offer the children of the poor, often segregated in schools of low quality, deficient opportunities to learn skills that help them improve their circumstances, whereas they provide children from more affluent circumstances opportunities to gain knowledge and skills that give them access to participate economically and civically. In doing so, schools serve as a structural mechanism that reproduces inequality, and indeed legitimize it as they obscure the structural forces that sort individuals into lives of vastly different well-being with an ideology of meritocracy that in effect blames the poor for the circumstances that their lack of skills lead to, when they have not been given effective opportunities to develop such skills.

There is abundant evidence of the vastly different learning outcomes achieved by students from different social origins, and of the differences in the educational environments they have access to. In the most recent assessment of student knowledge and skills conducted by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the socioeconomic status of students is significantly correlated to student achievement in literacy, math, and science in all 76 countries participating in the study (OECD, 2019). On average, among OECD countries, 12% of the variance in reading performance is explained by the socioeconomic background of the student. The strength of this relationship varies across countries, in some of them it is lower than the average as is the case in Macao (1.7%), Azerbaijan (4.3%), Kazakhstan (4.3%), Kosovo (4.9%), Hong Kong (5.1%), or Montenegro (5.8%). In other countries, the strength of the relationship between socioeconomic background and reading performance is much greater than the average such as in Belarus (19.8%), Romania (18.1%), Philippines (18%), or Luxembourg (17.8%). A significant reading gap exists between the students in the bottom 25% and those in the top 25% of the socioeconomic distribution, averaging 89 points, which is a fifth of the average reading score of 487, and almost a full standard deviation of the global distribution of reading scores in PISA. In spite of these strong associations between social background and reading achievement, there are students who defy the odds; the percentage of students whose social background is at the bottom 25%—the poorest students—whose reading performance is in the top 25%—academically resilient students—averages 11% across all OECD countries. This percentage is much greater in the countries where the relationship between social background and achievement is lower. In Macao, for instance, 20% of the students in the top 25% of achievement are among the poorest 25%. In contrast, in countries with a strong relationship between socioeconomic background and reading achievement, the percentage of academically resilient students among the poor is much lower, in Belarus and Romania it is 9%. These differences in reading skills by socioeconomic background are even more pronounced when looking at the highest levels of reading proficiency, those at which students can understand long texts that involve abstract and counterintuitive concepts as well as distinguish between facts and opinions based on implicit clues about the source of the information. Only 2.9% of the poorest students, compared with 17.4% among the wealthier quarter, can read at those levels of proficiency on average for the OECD (OECD, 2019b, p. 58). Table 1.1 summarizes socioeconomic disparities in reading achievement. The relationship of socioeconomic background to students’ knowledge and skills is stronger for math and science. On average, across the OECD, 13.8% of math skills and 12.8% of science skills are predicted by socioeconomic background.

The large number of children who fail to gain knowledge and skills in schools has been characterized, by World Bank staff and others, as ‘a global learning crisis’ or ‘learning poverty’, though the evidence on the strong correlation of learning poverty to family poverty suggests that this should more aptly be characterized as ‘the learning crisis for the children of the poor’ (World Bank, 2018). These low levels of learning have direct implications for the ability of students to navigate the alternative education arrangements put in place to educate during the pandemic; clearly students who can read at high levels are more able to study independently through texts and other resources than struggling readers.

The second interrelated challenge is that of ensuring that what ALL children learn in school is relevant to the challenges of the present and, most importantly, of the future. While the challenge of the relevance of learning is not new in education, the rapid developments in societies, resulting from technologies and politics, create a new urgency to address it. For students with the capacity to set personal learning goals, or with more self-management skills, or with greater skills in the use of technology, or with greater flexibility and resiliency, or with prior experience with distance learning, it was easier to continue to learn through the remote arrangements established to educate during the pandemic than it was for students with less developed skills in those domains. While the emphasis on the development of such breadth of skills, also called twenty-first century skills, has been growing around the world, as reflected in a number of recent curriculum reforms, there are large gaps between the ambitious aspirations reflected in modern curricula and standards, and the implementation of those reforms and instructional practice (Reimers, 2020b; Reimers, 2021).

The challenges of low efficacy and relevance have received attention from governments and from international development agencies, including the United Nations and the OECD. The UN Sustainable Development Goals, for instance, propose a vision for education that aligns with achieving an inclusive and sustainable vision for the planet, even though, by most accounts, the resources deployed to finance the achievement of the education goal fall short with respect to those ambitions. In 2019 UNESCO’s director general tasked an international commission with the preparation of a report on the Futures of Education, focusing in particular on the question of how to align education institutions with the challenges facing humanity and the planet.

1.5 The Pandemic and Health

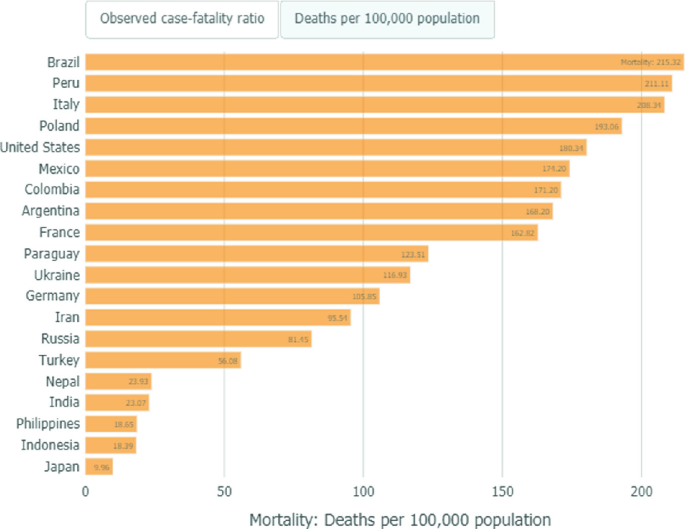

The main direct effect of the Coronavirus disease is in infecting people, compromising their health and in some cases causing their death. By May 27 of 2021, 168,040,871 people worldwide had become infected, of whom 3,494,758 had died reportedly from COVID-19 (World Health Organization, 2021a) and an additional 3 million had likely died from COVID-19 as they were excess deaths relative to the total number of deaths the previous year (World Health Organization, 2021b). As expected, more people are infected in countries with larger populations, but the rate of infection by total population and the rate of deaths by total population suggest variations in the efficacy of health policies used to contain the spread as shown in Fig. 1.4, which includes the top 20 countries with the highest relative number of COVID-19 fatalities. These differences reflect differences in the efficacy of health policies to contain the pandemic, as well as differences in the response of the population to guidance from public health authorities. Countries in which political leaders did not follow science-based advice to contain the spread, and in which a considerable share of the population did not behave in ways that contributed to mitigate the spread of the virus, not wearing face masks or socially distancing for instance, such as in Brazil and the United States, fared much poorer than those who did implement effective public health containment measures such as China, South Korea, or Singapore, with such low numbers of deaths per 100,000 people that they are not even on this chart of the top 20.

Source Johns Hopkins University. Coronavirus Resource Center (2021)

Number of reported COVID-19 deaths per 100,000 population in the 20 countries with the highest rates as of May 27, 2021.

1.6 The Pandemic, Poverty, and Inequality

The social distancing measures limited the ability of business to operate, reducing household income and demand. This produced an economic recession in many countries. For example, in the United States, 43% of small businesses closed temporarily (Bartik et al., 2020).

A household survey in seventeen countries in Latin America and the Caribbean demonstrates that the COVID-19 pandemic differentially impacted households at different income levels. The study shows significant and unequal job losses with stronger effects among the lowest income households. The study revealed that 45% of respondents reported that a member of their household had lost a job and that, for those owning a small family business, 58% had a household member who had closed their business. These effects are considerably more pronounced among the households with lower incomes, with nearly 71 percent reporting that a household member lost their job and 61 percent reporting that a household member closed their business compared to only 14 percent who report that a household member lost their job and 54 percent reporting that a household member closed their business among those households with higher incomes (Bottan et al., 2020).

It is estimated that the global recession augmented global extreme poverty by 88 million people in 2020, and an additional 35 million in 2021 (World Bank, 2020). A survey conducted by UNICEF in Mexico documented a 6.7% increase in hunger and a 30% loss in household income between May and July of 2020 (UNICEF México, 2020).

Because schools in some countries offer a delivery channel for meals as part of poverty reduction programming, several countries created alternative arrangements during the pandemic to deliver those or replaced them with cash transfer programs. Sao Paulo, Brazil, for instance, created a cash transfer program “Merenda en Casa’’ to replace the daily meal school programs (Dellagnelo & Reimers, 2020; Sao Paulo Government, 2020).

In the summer of 2020, Save the Children conducted a survey of children and families in 46 countries to examine the impact of the crisis, focusing on participants in their programs, other populations of interest, and the general public. The report of the findings for program participants—which include predominantly vulnerable children and families—documents violence at home, reported in one third of the households. Most children (83%) and parents (89%) reported an increase in negative feelings due to the pandemic and 46% of the parents reported psychological distress in their children. For children who were not in touch with their friends, 57% were less happy, 54% were more worried, and 58% felt less safe. For children who could interact with their friends less than 5% reported similar feelings. Children with disabilities showed an increase in bed-wetting (7%) and unusual crying and screaming (17%) since the outbreak of the pandemic, an increase three times greater than for children without disabilities. Children also reported an increase in household chores assigned to them, 63% for girls and 43% for boys, and 20% of the girls said their chores were too many to be able to devote time to their studies, compared to 10% of boys (Ritz et al., 2020).

1.7 Readiness for Remote Teaching During a Pandemic

Countries varied in the extent to which they had, prior to the pandemic, supported teachers and students in developing the capacities to teach and to learn online, and they varied also in the availability of resources which could be rapidly deployed as part of the remote strategy of educational continuity. Table 1.2 shows the extent to which teachers were prepared to use Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) in their teaching based on a survey administered by the OECD in 2018. The percentage of teachers who report that the use of ICT was part of their teacher preparation ranges from 37 to 97%. There is similar variation in the percentage of teachers who feel adequately prepared to use ICT, or who have received recent professional development in ICT, or who feel a high need for professional development in ICT. There is also quite a range in the percentage of teachers who regularly allow students to use ICT as part of their schoolwork.

This variation, along with variation in availability of technology and connectivity among students, creates very different levels of readiness to teach remotely online as part of the strategy of educational continuity during the interruption of in-person instruction.

1.8 What are the Short-term Educational Impacts of the Pandemic?

The study of the ways in which the pandemic can be expected to influence the opportunity to learn can be based on what is known about the determinants of access to school and learning, drawing on research predating the pandemic.

Opportunity to learn can be usefully disaggregated into opportunity to access and regularly attend school, and opportunity to learn while attending and engaging in school. John Carroll proposed a model for school learning which underscored the primacy of learning time. In his model, learning is a function of time spent learning relative to time needed to learn. This relationship between aptitude (time needed to learn) and learning is mediated by opportunity to learn (amount of time available for learning), ability to understand instruction, quality of instruction, and perseverance (Carroll, 1963).

In a nutshell, the pandemic limited student opportunity for interactions with peers and teachers and for individualized attention—decreasing student engagement, participation, and learning—while augmenting the amount of at-home work which, combined with greater responsibilities and disruptions, diminished learning time while increasing stress and anxiety, and for some students, aggravated mental health challenges. The pandemic also increased teacher workload and stress while creating communication and organizational challenges among school staff and between them and parents.

Clearly the pandemic constrained both the home conditions and the school conditions that support access to school, regular attendance, and time spent learning. The alternative strategies deployed to sustain the continuity of schooling in all likelihood only partially restored opportunity to learn and quality of instruction. Given the lower access that disadvantaged students had to technology and connectivity, and the greater likelihood that their families were economically impacted by the pandemic, it should be expected that their opportunities to learn were disproportionately diminished, relative to their peers with more access and resources and less stressful living conditions.

As a result of these constraints on opportunity to learn, the most vulnerable students were more likely to disengage from school. Such disengagement is, in effect, a form of school dropout, at least temporarily. As students fall behind because of their lack of engagement, this further diminishes their motivation, leading to more disengagement. It is possible that such a form of temporary dropout may lead to permanent dropout as learners take on other roles, and as learning recovery and catch up become more difficult as they fall further behind in terms of curricular expectations. The children who drop out will add to the already large number of children out of school, 258 million in 2018 (UNESCO, 2018). UNESCO has estimated that 24 million children are at risk of not returning to school (UNESCO, 2020a) which would bring the total number of out of school children to the same level as in the year 2000, in effect wiping out two decades of progress in educational access (UNESCO, 2020c, 2). These estimates are based on the following likely processes: (a) educational and socioemotional disengagement, (b) increased economic pressure, and (c) health issues and safety concerns (UNESCO, 2020a).

In addition to the direct impact of the health and economic shocks on student engagement, the lack of engagement of students was a function of the inadequacy of government efforts to sustain education through alternative means and the circumstances of students. In Mexico, for instance, the Federal Ministry of Education in Mexico closed schools on March 23, 2020; these closures remained in effect for at least a year. When the academic year began on August 24, 2020, the government deployed a national strategy for education continuity consisting of remote learning through television, complemented by access to digital platforms such as Google and local radio educational programming, with programs of teacher professional development on basic ICT skills to engage students remotely (World Bank, 2020c; SEP, Boletín 101, 2020). A television strategy was adopted for education continuity during the pandemic since only 56.4% of households have internet access, while 92.5% have a television (INEGI, 2019) and Mexico has a long-standing program of TV secondary school (Ripani & Zucchetti, 2020). Since March 2020, educational television content was delivered through Aprende en Casa I, II, and III (Learning at Home). Some Mexican states complemented the national strategy with additional measures, such as radio programs and textbook distribution, which were planned locally (World Bank, 2020c). Indigenous communities were also reached in 15 indigenous languages through partnerships with local radio networks (Ripani & Zucchetti, 2020). The State of Quintana Roo, for example, which has a large Mayan population, produced and distributed educational workbooks for students on various subjects written both in Spanish and Mayan languages (SEQ, 2020). The State Secretary of Education also created a YouTube channel with video lessons and a public television channel, within Quintana Roo’s Social Communication system, that was solely dedicated to the distribution of educational content (Gonzáles, 2020; Hinckley et al., 2021).

While the choice of a TV-based strategy for education continuity was predicated on the almost universal accessibility to television, and on a long tradition of the Ministry of Education producing educational TV (Telesecundaria), a survey conducted in June 2020 by an agency of the Mexican government showed that 57.3% of the students lacked access to a computer, television, radio, or cell phone during the emergency and 52.8% of the strategies required materials that students did not have in their homes (MEJOREDU, 2020a). In the same survey, 51.4% of students reported that the activities online, on the TV, and on radio programs were boring (MEJOREDU, 2020a). Students reported challenges to learning stemming from limited support or lack of explanations from their teachers, lack of clarity in the activities they were supposed to carry out, limited feedback on the work completed, lack of knowledge about their successes or mistakes in the activities, insufficient understanding of what they were doing, less learning and understanding, and perception of not having the necessary knowledge to pass onto the next grade. More than half of the students (60% at the primary level and 44% at the secondary level) indicated that during the period of remote learning they had simply reviewed previously taught content (MEJOREDU, 2020a).

The same study canvassed teachers for their views on factors which prevented student engagement, 84.6% of the teachers mentioned lack of internet access, 76.3% mentioned lack of electronic devices to access activities, and 73.3% mentioned limited economic resources (MEJOREDU, 2020a, p. 10). Students, in turn, reported the following as factors which excluded them: difficulty in following the activities (“it’s difficult,” “I don’t understand,” “I don’t have time”) followed by stress or frustration, the need to attend to housework, obligation to take care of other people, and lack of motivation expressed as laziness, tiredness, boredom, loss of interest, or discouragement. Half of the students reported that the tasks involved in learning remotely caused stress and 40% reported sadness and low levels of motivation (MEJOREDU, 2020a, p. 10).

Mexico’s approach to education continuity is illustrative of the approach followed by many other countries. Costa Rica, for example, also closed down schools upon the declaration of a national emergency in March 2020, transitioning to a virtual school program, delivered through an online program, and a distance learning program that varied throughout different cantons in the country (Diaz Rojas, 2020). These were supplemented by an educational television program of two hours a day during weekdays for students in the upper elementary grades, a daily one-hour radio program augments these efforts. Five months after the initiation of the virtual strategy, 35% of the students had not logged into the free online accounts provided to them by the Ministry (Direccion de Prensa y Relaciones Publicas, 2020).

Bangladesh also closed schools on March 16th, 2020, and gradually extended what was to be a two week lock down for at least a year, relying on a distance learning strategy of education continuity relying on internet, TV, radio, and mobile phones, which had serious challenges reaching students in a country where only 13% of the population used the internet in 2019 and only 5.6% of households have access to a computer (World Bank, 2019). Access to TV was greater, reaching 56% of the households, but very few had access to radio (0.6% of the population). While access to mobile phones was greater it was not universal, with 92% of families in the lowest wealth quintile with access to mobile phones, but only 19% of the total population with access to a smartphone (Bell et al., 2021; World Bank, 2019).

Some countries found the prospects of developing alternative forms of education continuity so daunting that they suspended the school year entirely. In Kenya, for instance, by July of 2020 the Ministry of Education had decided to close all public schools in the country until January 2021 and then restart the academic school year. The decision was revised in October of 2020, with a partial reopening of schools for the grades in which students take exams (grade 4, class 8, and form 4) in order to prepare students for the official school-leaving examinations and for critical transitions (Voothaluru et al., 2021).

In South Africa, COVID-19 was met by wide-scale school closures, with no practical way to shift to remote learning given lack of student access to the internet (Statistics South Africa, 2019; UNICEF, 2020). In September 2020, schools reopened after several months of being closed, only to close again in January 2021, during the second wave of the pandemic (UNICEF, 2020).

Even well-resourced countries shifted to remote instruction for at least a short period. In the United Arab Emirates, for instance, the Ministry of Education shifted education to remote learning from March to June 2020. Upon resuming in-person instruction at the start of the new academic year, however, families had the discretion to choose whether to participate fully in-person, fully online, or in blended learning modalities. In spite of the strong commitment to inclusion of people with disabilities in the UAE, providing adequate accommodations for them was challenging (Mohajeri et al., 2021).

Among the many challenges faced by schools and education systems, as they relied on these alternative forms of educational continuity, was the assessment of students’ knowledge. Many national assessments were cancelled. Absence of information on student knowledge and skills prevented determining the extent of learning loss and the implementation of remedial programs to address it. Other challenges stemmed from teachers’ limited skills in teaching remotely, as shown earlier.

While the lack of reliable assessments of learning loss to date prevent estimating the full impact of the pandemic for most countries in the world, the limited studies available document deep impacts, particularly for disadvantaged students. A recent study conducted in Belgium, where schools were closed for approximately nine weeks, shows significant learning losses in language and math (a decrease in school averages of mathematics scores of 0.19 standard deviations and of Dutch scores of 0.29 standard deviations as compared to the previous cohort) and an increase in inequality in learning outcomes by 17% for math and 20% for Dutch, in part a result of increases in inequality between schools (an increase in between school inequality of 7% for math and 18% for Dutch). Losses are greater for schools with a higher percentage of disadvantaged students (Maldonado, De Witte, 2020). A review of this and seven additional empirical studies of learning loss, of which one focused on higher education, finds learning loss also in the Netherlands, the United States, Australia, and Germany, although the amount of learning loss is lower than in the study in Belgium. A study in Switzerland finds learning loss to be insignificant and a study in Spain finds learning gains during the pandemic (Donnelly & Patrinos, 2021, 149). These seven out of eight studies that identified learning loss were conducted in countries where education systems were relatively well-resourced and covered relatively short periods of school closures: 9 weeks in Belgium, 8 weeks in the Netherlands, 8 weeks in Switzerland, 8–10 weeks in Australia, and 8.5 weeks in Germany (Ibid). The studies also show that while there is consistent learning loss for primary school students, this is not the case for secondary and higher education students.

In addition to the losses in educational opportunity just described, there may be some silver linings resulting from this global education calamity. The first is that the interruption of schooling made visible how important teachers and schools are to support learning, and how many other activities depend on the ability of schools to carry out their role effectively. As teachers had to depend on parents to support students in learning more than is habitual under regular circumstances, this may have created valuable opportunities for mutual recognition between teachers and parents. As each of these groups is now more cognizant of what the other does, perhaps they have learned to collaborate more effectively. Increased parental involvement in the education of their children may have also strengthened important bonds and further developed parenting skills. For some children, it is possible that the freedom from the routines and constraints of schools, and from some of the social pressures resulting from interaction with peers, may have provided opportunities to learn independently and for greater focus, depth, and reflection.

The emergency also made visible the importance of attending to the emotional well-being of students and showed that integrating this as part of the work of schools is not only intrinsically valuable, but also part and parcel of a good education. In attempting to provide emotional support to students, teachers also had to re-prioritize the curriculum, engaging in a valuable exercise of rethinking what is truly important for students to learn. Facing the challenge of reprioritizing the curriculum, some countries embarked on a process of revision for the long haul.

For instance, the South African Directorate of Basic Education has taken a multi-pronged approach to address this complex set of issues. Two such approaches include (1) A short-term―3 year―education recovery plan in response to COVID-19, to address learning loss, and (2) A medium to long-term curriculum modernization plan (2024 onward), aimed at addressing the issue of curriculum relevance and preparing learners for the fast-changing world. The Directorate of Basic Education is working with the National Education Collaboration Trust (NECT) to establish a Competency-Infused Curriculum Task Team (CICTT) mandated to conceptualize and provide a set of policy and implementation recommendations for a modernized curriculum (Eadie et al., 2021).

Creating alternative forms of education delivery during the emergency provided an opportunity for innovation and creativity, an opportunity that many teachers took up, demonstrating outstanding professionalism. The organizational conditions which unleashed such creativity and professionalism need to be better understood, as they may represent a valuable dividend generated by this pandemic, which could be usefully carried forward into the future.

1.9 Methods

To contribute to this book, in July of 2020 I invited colleagues from fifteen educational institutions, the majority of whom are university-based researchers in a variety of countries reflecting various regions of the world and varied education systems in terms of the salient challenges facing those systems and the levels of education spending across them. We agreed to conduct case studies that would analyze available empirical evidence to address the questions below. The case studies were conducted between August of 2020 and January of 2021. We then met at a virtual conference in February of 2021 to discuss the draft chapters, and then finalized them by April of 2021 based on feedback received from other contributors to the project.

-

1.

When did the COVID-19 pandemic reach national attention in the country? Is there a specific date when the government declared a national COVID-19 emergency? What educational policies followed that declaration? Was attendance to school suspended? Where in the school year did this happen –was it the beginning of the school year, the middle or the end?

-

2.

What policy responses were adopted at various stages during the pandemic to sustain educational opportunity? Were there alternative means of education delivery created? Was the curriculum reprioritized? Were platforms for online learning created? Educational radio? Television? Were there special efforts to support the education of marginalized students?

-

3.

What is known about the impact of the pandemic on educational opportunities in the country, for different groups of students? Is there evidence on the degree to which children remained enrolled in school, engaged in their studies, learning?

-

4.

Are there any educational positive effects of the pandemic? Any silver linings? Lessons learned that would be of benefit to education in the future.

-

5.

What is known about the effects of the alternative means of delivery put in place, if any?

-

6.

Given current knowledge, what are the likely educational implications of the pandemic?

-

7.

What are the areas in which more research is needed?

-

8.

What are areas that merit policy attention during the remaining period of the pandemic, and beyond?

In addition to a chapter with a global focus, and a chapter comparatively examining five OECD countries, the book includes chapters focusing on Brazil, Finland, Japan, Mexico, Norway, Portugal, Russia, Singapore, Spain, South Africa, and the United States. A concluding chapter discusses some of the threads running through the cases and the implications of the findings.

What follows is a rich and complex story. While most children of the world experienced some form of educational interruption, the extent and depth varied among countries and among groups of children. Understanding the details of how education systems were more able to preserve educational opportunity for some children and in some countries is crucial to discern what was lost, what lies ahead, and what we can expect from schools as institutions that can build a future that is better than the present or the past.

References

Alvarez Marinelli, H., et al. (2020). La Educacion en Tiempos del Coronavirus. Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo. Sector Social. Division de Educación.

Bell, P., Hosain, M., & Ovitt, S. (2021). Future-proofing digital learning in Bangladesh: A case study of a2i. In Reimers, F., Amaechi, U., Banerji, A., & Wang, M. (Eds.) (2021). An educational calamity. Learning and teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. Independently published, pp. 43–59.

Bottan, N., Hoffmann, B., Vera-Cossio, D. (2020). The unequal impact of the coronavirus pandemic: Evidence from seventeen developing countries. PLoS One, 15(10), e0239797.

Carroll, J. B. (1963). A model for school learning. Teachers College Record,64, 723–733.

Coadi, D., & Dizioli, A. (2017). Income Inequality and Education Revisited: Persistence, Endogeneity, and Heterogeneity IMF Working Paper Fiscal Affairs Department.

Dellagnelo, L., & Fernando, R. (2020). Brazil: Secretaria Estadual de Educação de São Paulo (São Paulo State Department of Education). Education continuity stories from the coronavirus crisis. OECD Education and Skills Today. Retrieved from https://oecdedutoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Brazil-S%C3%A3o-Paulo-State-Department-of-Education.pdf.

Diaz Rojas, K. (2020, March 3). MEP lanza estrategia “Aprendo en casa”. Retrieved from http://mep.go.cr/noticias/mep-lanza-estrategia-%E2%80%9Caprendo-casa%E2%80%9D-0.

Direccion de Prensa y Relaciones Publicas. (2020, August 27). MEP anuncia el no retorno a las clases presenciales durante el 2020. Retrieved from https://www.mep.go.cr/noticias/mep-anuncia-no-retorno-clases-presenciales-durante-2020.

Donnelly, R., & Patrinos, H. (2021). Learning loss during COVID-19: An early systematic review. Covid Economics, 77(30 April 2021), 145–153.

Eadie, S., Villers, R., Gunawan, J., & Haq, A. (2021). In Reimers, F., Amaechi, U., Banerji, A., & Wang, M. (Eds.), 2021. An educational calamity. Learning and teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. Independently published, pp. 277–311.

Giannini, S. (2020). Distance Learning Denied. Over 500 million of the world’s children and youth not accessing distance learning alternatives. Retrieved 10 February, 2021, from https://gemreportunesco.wordpress.com/2020/05/15/distance-learning-denied/.

González, C. J. (2020, September 8). Mensaje del gobernador Carlos Joaquín a la ciudadanía, en ocasión del 4º Informe de Gobierno, desde el C5 en Cancún. Gobierno Quintana Roo, Mexico. Retrieved from https://qroo.gob.mx/cuartoinforme/index.php/2020/09/08/texto-mensaje-del-gobernador-carlos-joaquin-a-laciudadania-en-ocasion-del-4o-informe-de-gobierno-desde-el-c5-en-cancun-8-deseptiembre-de-2020/.

Hallgarten, J. (2020, March 31). Evidence on efforts to mitigate the negative educational impact of past disease outbreaks. Institute of Development Studies. Reading, UK: Education Development Trust, (Report 793).

Hanushek, E. A., & Woessmann, L. (September 2020). The economic impact of learning losses. Education Working Papers, No. 225. OECD Publishing.

Hinckley, K., Jaramillo, M., Martinez, D., Sanchez, W., & Vazquez, P. (2021). In Reimers, F., Amaechi, U., Banerji, A., & Wang, M. (Eds.), 2021. An educational calamity. Learning and teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. Independently published, pp. 191–235.

Irwin, A. (2021). What will it take to vaccinate the world against COVID-19? Nature,592, 176–178.

Johns Hopkins University. Coronavirus Resource Center. Retrieved 27 Mary, 2021, from https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html.

Jackson, C., Vynnycky, E., Hawker, J., et al. (2013). School closures and influenza: Systematic review of epidemiological studies. BMJ Open, 3, e002149.

Maldonado, J. E., & DE Witte, K. (2020). The effect of school closures on standardised student test outcomes. KU Leuven. Department of Economics. DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES DPS20.17 SEPTEMBER 2020.

Markel, H., Lipman, H., Navarro, J. A., et al. (2007). Nonpharmaceutical interventions implemented by US cities during the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic. JAMA, 298(6), 644–654.

Mayer, S. (2010). The relationship between income inequality and inequality in schooling.Theory and Research in Education, 8(1), 5–20.

MEJOREDU, Comisión Nacional para la Mejora Continua de la Educación. (2020a). Experiencias de las comunidades educativas durante la contingencia sanitaria por COVID-19. Educación básica. Informe Ejecutivo. Retrieved from https://editorial.mejoredu.gob.mx/ResumenEjecutivo-experiencias.pdf.

Mohajeri, A., Monroe, S., & Tyron, T. (2021). In Reimers, F., Amaechi, U., Banerji, A., & Wang, M. (Eds.) (2021). An educational calamity. Learning and teaching during the covid-19 pandemic. Independently published, pp. 313–344.

OECD. (2019). PISA 2018 Results. Volume 1 What Students Know and Can do and 2.

OECD. (2019b). PISA 2018 Results. Volume 2. Where all Students can succeed.

Reimers, F., & Schleicher, A. (2020a). Schooling Disrupted. Schooling Rethought. How the COVID-19 pandemic is changing education. OECD.

Reimers, F. (Ed.). (2020). Audacious education purposes. Springer.

Reimers, F. (Ed.). (2021). Implementing deeper learning and 21st century education reforms. Springer.

Reimers, F., Amaechi, U., Banerji, A., & Wang, M. (Eds.). (2021). An educational calamity. Learning and teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. Independently published.

Ripani, F., & Zucchetti, A. (2020). Mexico: Aprende en Casa (Learning at home), Education continuity stories series. OECD. World Bank Group. HundrED. Global Education Innovation Initiative. Retrieved from https://oecdedutoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Mexico-Aprende-en-casa.pdf.

Ritz, D., O’Hare, G., & Burgess, M. (2020). The hidden impact of COVID-19 on child protection and wellbeing. Save the Children International. Retrieved from https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/node/18174/pdf/the_hidden_impact_of_covid-19.

Sao Paulo Government. (2020). Merenda em Casa. São Paulo Governo do Estado. Brazil. Retrieved from https://merendaemcasa.educacao.sp.gov.br/.

SEP, Secretaría de Educación Pública. (2020, April 22). Boletín No. 101. Quintana Roo. Mexico. Retrieved from https://www.gob.mx/sep/articulos/boletin-no-101-inicia-sep-en-colaboracion-con-googlecapacitacion-virtual-de-mas-de-500-mil-maestros-y-padres-de-familia?idiom=es.

SEQ Secretaría de Educación de Quintana Roo. (2020). Guías De Experiencias Quintana Roo / Ciclo Escolar 2020–2021. Edited by Secretaría de Educación de Quintana Roo SEQ. Gobierno Del Estado Quintana Roo, 2016–2022. Retrieved from https://www.qroo.gob.mx/seq/guias-de-experiencias-quintana-roo-ciclo-escolar-2020-2021.

Smeeding T. (2012). Income, wealth, and debt and the Great Recession; A great recession brief. Retrieved from http://web.stanford.edu/group/recessiontrends-dev/cgi-bin/web/sites/all/themes/barron/pdf/IncomeWealthDebt_fact_sheet.pdf.

Statistics South Africa. (2020). Vulnerability of youth in the South African labour market. Q1: 2020. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/3pgYARd.

UNESCO. (2018). 4.1.5―Out-of-school rate (primary, lower secondary, upper secondary): Technical Cooperation Group on the Indicators for SDG 4. UNESCO. Retrieved from http://tcg.uis.unesco.org/4-1-5-out-of-school-rate-primary-lower-secondary-upper-secondary/.

UNESCO. (2020). “290 million students out of school due to COVID-19: UNESCO releases first global numbers and mobilizes response". 2020–03–12. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20200312190142/https:/en.unesco.org/news/290-million-students-out-school-due-covid-19-unesco-releases-first-global-numbers-and-mobilizes.

UNESCO 2020a. (2020a, June 08). UN Secretary-General warns of education catastrophe, pointing to UNESCO estimate of 24 million learners at risk of dropping out. PRESS RELEASE. Retrieved from https://en.unesco.org/news/secretary-general-warns-education-catastrophe-pointing-unesco-estimate-24-million-learners-0.

UNESCO 2020c. (2020, July 30). UNESCO COVID-19 Education Response: How many students are at risk of not returning to school? Advocacy Paper. Retrieved from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373992.

UNESCO. (2021). UNESCO figures show two thirds of an academic year lost on average worldwide due to COVID-19 school closures. Retrieved 20 February, 2021, from https://en.unesco.org/news/unesco-figures-show-two-thirds-academic-year-lost-average-worldwide-due-covid-19-school.

UNESCO, UNICEF and the World Bank. (2020). WHAT HAVE WE LEARNT? Overview of findings from a survey of ministries of education on national responses to COVID-19. Retrieved 10 February, 2021 from http://tcg.uis.unesco.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2020/10/National-Education-Responses-to-COVID-19-WEB-final_EN.pdf.

UNICEF South Africa. (2020). UNICEF Education COVID-19 Case Study. South Africa. Retrieved 20 February, 2021, from https://bit.ly/3dcr7oY.

UNICEF Mexico. (2020, May 15). Encuesta #ENCOVID19Infancia. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/mexico/informes/encuesta-encovid19infancia.

United Nations. (2020, August). Policy brief: Education during COVID-19 and beyond.Retrieved from https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/sg_policy_brief_covid-19_and_education_august_2020.pdf.

United Nations. (2021). Inequality. Bridging the Divide.

Voothaluru, R., Hinrichs, C., & Pakebusch, M. R. (2021). In Reimers, F., Amaechi, U., Banerji, A., & Wang, M. (Eds.), 2021. An educational calamity. Learning and teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. Independently published, pp. 163–190.

World Bank. (2018). World Development Report 2018. Learning to Realize Education’s Promise. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2018.

World Bank. (2019). Ending learning poverty: A target to galvanize action on literacy. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/immersive-story/2019/11/06/a-learning-target-for-a-learning-revolution.

World Bank. (2020a). COVID-19 to Add as Many as 150 Million Extreme Poor by 2021. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/10/07/covid-19-to-add-as-many-as-150-million-extreme-poor-by-2021.

World Bank 2020b. (2020, June 18). Simulating the potential impacts of the COVID-19 school closures on schooling and learning outcomes: A set of global estimates. IBRD-IDA. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/education/publication/simulating-potential-impacts-of-covid-19-school-closures-learning-outcomes-a-set-of-global-estimates.

World Bank. (2020c). Education systems’ response to COVID-19: Brief. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/data/interactive/2020/03/24/world-bank-education-and-covid-19.

World Bank. (2020d). Individuals using the Internet (% of population)―Bangladesh. (2019). Retrieved December 12, 2020, from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS?locations=BD.

World Health Organisation (WHO). (2020a). Statement on the second meeting of the international health regulations (2005) Emergency committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Published 30 January 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meetingof-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novelcoronavirus-(2019-ncov).

WHO. (2020b). WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. Published 11 March 2020. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-openingremarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020.

WHO. (2021a). WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Retrieved 27 May, 2021, from https://covid19.who.int/.

WHO. (2021b). COVID-19 Global excess mortality. Retrieved 27 May, 2021, from https://www.who.int/data/stories/the-true-death-toll-of-covid-19-estimating-global-excess-mortality.

WHO. (2021c). Director General Remarks at the 2021 World Health Assembly. Retrieved 27 May, 2021, from https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-world-health-assembly---24-may-2021.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Reimers, F.M. (2022). Learning from a Pandemic. The Impact of COVID-19 on Education Around the World. In: Reimers, F.M. (eds) Primary and Secondary Education During Covid-19. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81500-4_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81500-4_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-81499-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-81500-4

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)