Abstract

The COVID-19 crisis has challenged the evaluation profession by altering the framework within which it operates. Evaluators must embrace new realities and respond to changes while not altering their principles, norms, and standards.

A review of how evaluation networks and offices have responded to changing demands showed lack of recognition for the long-term implications to the profession. Commissioners and users of evaluation now have new priorities, and nontraditional actors have entered the traditional evaluation space, offering similar expertise and meeting the demands of evaluation commissioners and users. The extensive development challenges posed by COVID-19 require a comprehensive response capacity from evaluation if it is to be transformative as a profession.

This chapter draws on national and international case studies, examining the concept of transformation from a contextual perspective and noting the relativism in the concept. It draws links between aspects, suggesting that this period is an opportunity for evaluators to learn from practice around transformation, and suggests that flexibility provides an opportunity to remain relevant and advance transformational goals.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Evaluation Must Respond to Global Signals to Be Relevant

This chapter draws on the special session on evaluation for transformation at the 2019 International Development Evaluation Association (IDEAS) conference. Since then, major changes have occurred globally, changing concepts on development and redefining its assessment. The changes in the development discourse mean that multiple reprioritizations are taking place, with major impacts on the global financial, governance, accountability, and knowledge generation systems. Operating within these contexts—and within authorizing political and social contexts—evaluation practice cannot remain detached or static. The new era has triggered new demands for evaluative knowledge and products, now met by the research sector broadly, thereby diminishing the exclusivity that evaluators once held on evaluative knowledge and outputs. Unless evaluation can demonstrate a more compelling value proposition that moves beyond serving traditional oversight and accountability needs, it may lose its privileged position. Its continued relevance will be questioned.

Evaluation does not occur in a vacuum but responds to demands, imperatives, and contexts, which explains both its uneven evolution and resultant variation across the globe. We have no commonly shared perspective as to what evaluation is and should achieve; with various camps of evaluation practice justifying their positions, we lack evaluation consensus and identity. Demonstrating context’s effect on research demand is the COVID-19 pandemic and United Nations (UN) response, which has taken the form of supporting countries’ production of socioeconomic assistance and recovery plans to ensure the most effective development interventions. Although reporting and review are key parts of the plans, they include little mention of evaluation. Such plans do not draw sufficiently from evaluative work at the country or global level. This may signal a marginalization of evaluation in favor of other forms of research during this period that requires more real-time monitoring information to support recovery than detailed and often late evaluation studies. In the era of big data, artificial intelligence, and other forms of data generation and extraction, evaluators are often not engaging with new realities.

Redefinition in the COVID-19 Crisis: Evaluators Are Not Isolated from Changes

With COVID-19 declared a global crisis in April 2020 by the Secretary-General of the United Nations (Guterres, 2020), the UN has responded to support the recovery of countries. One element of the UN response is research and analytical support to help decision making toward recovery. It has resulted in the generation of assessments on the state of development of countries around the world, with the aim of better understanding the impact of the crisis. Evaluation was affirmed for its role in guiding progress toward the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs; Mohammed, 2019). The context now, as indicated by Barbier and Burgess (2020), is one of declining resources and will require targeted interventions to mitigate the impact of the crisis and ensure that lives and livelihoods are protected, to help rebuild in a better, more sustainable manner. Barbier and Burgess specifically highlighted that some SDGs will be sacrificed during this period while focus is on SGDs to curb the spread of the virus and tackle the immediate economic fallout. It means that addressing the SDGs with equal priority will probably not occur, even if they are referenced as important.

All of the joint UN government plans reference the SDGs, which have served to date as milestones and targets for achieving Agenda 2030. The evaluation community has been active in supporting the SDGs through providing evaluation capacity to countries, a significant contribution. This is attested to in the proceedings of the National Evaluation Capacities Conference 2019 (United Nations Development Programme, Independent Evaluation Office [UNDP IEO], 2020), where countries presented case studies of their success in using evaluation for SDG attainment. In this context and until the 2020 pandemic, the form of evaluation considered valuable was that which built measurement capacity as a basis for advancing transformation. The emphasis was for evaluation to be people-centered, shown in both the Prague Declaration and, adopted in Egypt, the Hurghada Principles (UNDP IEO, 2020), which also called for a focus on people and collectivism. The UN principle of leaving no one behind, particularly focusing on vulnerable groups such as women, has emphasized the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on the poor. The proposed UN response, apart from acknowledging a serious loss of developmental gains, is to “build back better” (United Nations, 2020). Implicit in the statement is a transformational intention. Patton (2020), in his examination of what needs to change for evaluation to be transformative, asked for an acknowledgment of the changes. Prior to the crisis era, Feinstein (2019) suggested that evaluation could be more dynamic and support transformational change. In the current era, the potential role of evaluation in generating knowledge and creating processes for a more sustainable society, and the new order will be quite different (Schwandt, 2019). Therefore, evaluation that claims to be transformative must address these demands.

Challenges to Evaluation as a Practice and Form of Transformation

Interest in evaluation has increased, reflecting on its identity as a practice with the associated research stipulations and adherence, and questioning whether this practice, if pursued in a particular manner, can be transformative. These debates will continue and Feinstein (2017) argued that evaluation will also influence knowledge management, which is critical in the era of big data, artificial intelligence, and machine learning. Classic evaluation practices and associated norms are challenged as new research formations and data producers could influence the existing oversight architecture at the country and global levels affecting evaluation demand. Efficiency considerations will be important and the old professional boundaries between audit and evaluation may not be viewed as efficient and effective (Naidoo & Soares, 2020).

The Exploratory Nature of This Chapter

This chapter draws on personal experiences to reflect on the evaluation–transformation question from an evaluation leadership perspective. The two case studies demonstrate the relativism around the concept of transformation. In Patton’s (2020) discussion on Blue Marble Evaluation, he illustrated how the COVID-19 crisis has challenged the notion of the nation-state, and shown that the globe, instead, is highly interconnected with porous borders.

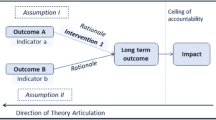

This may challenge evaluators who have traditionally worked within confined boundaries, departments, agencies, and country-level programs but seldom on a macro- and cross-cutting level, where issues of complexity and its multiple influences come in. Moving from units of analysis that are small and perceived as static toward addressing larger units of analysis with interconnections and influences is difficult and will be challenging in contexts of working with partners and big data, at scales larger than most evaluators deal with. This factor alone would challenge the prevalence of classic accountability evaluation, with its bias toward linear thinking and measurement. In this period, other actors will challenge the exclusive domain of judgment that evaluators have held. Very different requirements are now in place for governance in the accountability or fidelity era, as argued in Schwandt’s (2019) discussion on the post-normal era. Inevitably, as resources shift, so too will governance priorities, and this will affect evaluation, irrespective of its type.

Changes to the Evaluation–Transformation Relationships over Time

My work in the field of evaluation over the last 25 years has highlighted its relationship to power and its potential and constraints to be transformational. The broad definition of positive change is making advancements toward better quality standards, and, in the process, improving transparency and accountability. This is universally applicable and, in these contexts, prioritizes elements of fidelity to assure funders and citizens that the organization performs as expected. In this context, independence is an important component for accountability obligations (Schwandt, 2019).

Evaluation by its nature is judgmental and therefore triggers a set of managerial reactions that may not always resonate with the intention of evaluators. Evaluators privilege science and assume rationality in decision-making (Schwandt, 2005). Evaluation works on the assumption that evidence is central in decision-making contexts. The independent type of evaluation generates tensions in organizations given its profile and authority but is largely accepted as a part of organizational practice. The growth in the profession, even at the level of national authorities, has produced policies that show an understanding of the relationship between independence, credibility, and utility.

The Crisis Context and Potential Loss of Judgement Proprietorship

I caution that the word “transformation” has become cliché and used broadly to describe all changes, even those that would naturally evolve over time. Evaluation is often viewed as inherently progressive and transformative, but in practice, unless there are actions to drive this goal, it tends to fail.

In the context of COVID-19, evaluative sources (research think tanks, commissioned reviews, surveys, and social media streams) also feed directly to decision makers. Monitoring information is valued due to its timely delivery, and evaluators may lose their singular propriety to performance information. Further, they may lose their direct access to decision makers as governance and accountability architecture changes. Evaluators’ ability to directly access beneficiaries also will change, given the travel restrictions, and remotely generated evaluations will not carry the same level of authority as those generated from full engagement. The question is, what is the value proposition that evaluators bring into this new context? A further issue is whether the classic accountability framework for evaluation will remain dominant in the era of big data. This needs exploration.

Judging Transformation, the Challenge of Relativism

The backdrop against which an intervention takes place is important, as is whether evaluation is a practice to promote democracy. Many perspectives currently exist as to what transformative evaluation is but there is no consensus. Some scholars and practitioners identify transformation if the subject matter is inherently transformational, such as land reform or addressing discrimination. These are context specific and generally imply a form of redress, which evaluation measures and reports on. The transformative subject evaluations fall into those that promote democracy, as they generate public dialogue on performance for accountability purposes. One of the case studies I describe in this chapter relates to apartheid South Africa. In this context, evaluation was regarded as inherently transformative simply because it gave access to previously unavailable information. This may appear modest, but in such a context, against a backdrop of repression and state control, it was significant.

Context Ascribes Value and Meaning to the Concepts of Transformation

This discussion seeks to illustrate how context may attribute a higher value to change. The concept of positive transformation can be relative to how it brings about changes and is valued as such in these historical junctures. This is a value judgment and projected by a part of the evaluation community, reflecting both its diversity and differences in global growth (Naidoo, 2011, 2012).

This chapter also draws on examples from within the UN situation and highlights how aspects such as evaluation approach, methodology, and increasing evaluation outputs supported transformation. The key shift was moving from using an outsourced and consultant-driven model to a professional cadre one, which helped affect changes in learning and accountability (Naidoo, 2019).

Given the broad scope within this umbrella of political topics, as the case studies illustrate, few global standards exist to judge definitively whether or not evaluations are transformative. This chapter takes the definitional view of a transformational practice as one that brings about more fundamental changes in the sense of being able to trigger and/or sustain major changes on all fronts and meeting societal and developmental aspirations (attainment of SDGs). Transformational change could also include changes in professional identity and approach, showing evaluators as change agents, or redefining evaluation decision making and governance arrangements.

Changes in Evaluation Production and Emphasis

Evaluation, irrespective of what it is termed, is one of many streams of information to influence decision making (Rist & Stame, 2006). In the era of big data, artificial intelligence, and a more active research mode on the part of commissioners and receivers of evaluation (in the form of outputs of reports, briefings, etc.), evaluation is now part of a larger flow of information at decision makers’ disposal. Evaluators need to make stronger arguments about their value proposition when new scenarios, such as those caused by COVID-19, affect their work. It is too early to speculate how this will manifest, at what intensity and form, and in which countries. The new evaluation construct will probably involve very different engagement permutations than those currently in place.

The fidelity role of evaluation currently prevails and although this form has progressed and received much attention (Schwandt, 2019), it is a particular type of evaluation that on its own may not meet all of the transformative criteria of dynamic evaluation as espoused by Feinstein (2020). The fidelity type of evaluation may provide assurance of program value but may not necessarily address issues that move beyond the organizational scope or provide a foresight pitch as called for by Patton (2019). In the COVID-19 context, the classic evaluation criteria would also require another look. Ofir (2020) and Patton (2020) suggested new elements that capture the dynamic nature of changes in the context of the global pandemic. In Picciotto’s (2020) discussion on renewal of evaluation, he argues that the status quo cannot remain and evaluation must be able to produce changes that are more tangible.

When undertaking evaluation for purposes of accountability, the focus is on assessing results against plans. In contexts where evaluation is not independent and focused on supporting internal audiences, its plays a more facilitative, co-creative role toward a utility focus (Patton, 2018). In both these situations, the modus operandi would differ and the actual context would influence the extent to which evaluations may have transformational purposes. Results are challenged in both contexts, and often the self-assessment undertaken by program units tends to be more favorable on ratings than assessment provided by independent evaluation units. Greater organizational dialogue is necessary to help reconcile these differences, in the spirit that evaluation is a part of organizational learning using its independent principles to improve quality.

My personal reflections from various leadership functions also indicate that the passage of time can change one’s views and those of people involved at a specific time as to whether the work was truly transformational or, more modestly, contributory. The reflective approach in answering these questions is an appropriate methodology given the nascent state of development of the field of transformative evaluation.

Case Studies on the Evaluation–Transformation Nexus

South Africa National Department of Land Affairs and Public Service Commission

My work as a senior manager at the National Department of Land Affairs and the Public Service Commission (PSC) of South Africa in the post-apartheid era from 1995–2011 provided an opportunity as an evaluation professional to expand on the concept of evaluation for transformation. This was a period when the profession was still evolving as the country began establishing its own professional evaluation association. The South African Monitoring and Evaluation Association (SAMEA) was launched in 2005 and set the pace for important growth of the profession.

In my work at the National Department of Land Affairs from 1995–2000, the very function of monitoring and evaluation (M&E) did not naturally resonate with the administration. The argument was that policy was not negotiable. When assessments of the policy showed weaknesses, it took a long time for the administration to make changes. This was frustrating for evaluators who did not see adequate attention paid to evaluation. The production of basic performance information was regarded as more important than policy analysis and impact assessments.

In the still censorious but changing climate, little qualitative analysis of program worth occurred, the very modality of land reform delivery was examined, and complicated and costly processes meant rapidly rising frustrations among beneficiaries (Naidoo, 1997). Considered decades later, results show that the program continues to struggle because central issues raised at the early stage of the program were not addressed. The key question: When undertaking M&E of purportedly transformational programs, does one take the policy as a given and just assess progress, or does one have the space to question the basis of the policy?

The work of the PSC was to oversee the performance of the public service in using its powers and normative tools and measures to effect transformation. It was expressly set up as part of the democratic constitution to ensure good governance (Naidoo, 2010). This was enshrined in Chapter 10 of the constitution, which sets out nine principles and values for public administration that the PSC was to advance “without fear, favor or prejudice” (Naidoo, 2004, 2010). Its focus was on improving the capacity of the “developmental state,” which was viewed as the key driver for transforming government and the country from its unequal and racially divided past. It sought to advance equity and social and economic transformation as part of the democratic era. The annual work of the PSC culminated in a State of the Public Service report that meta-assessed the organization’s work against the constitution’s values and principles and its demonstrated progress or lack thereof. The PSC’s was a national transformation project that generated information to bring about changes to the South African public sector. However, multiple sources of information indicate governance failures persist.

The sentiment as of 2020 is that the country has not met the expectations of the developmental state, and admissions from the ruling party regarding governance deficits at multiple levels show that one organization, albeit with formal authority, cannot on its own effect transformation. It can assist, but only if those in power act. Thus, evaluation has limits as to what it can do, and its support for transformation would be modest at best in the context described. However, accumulatively with other such directed initiatives, it can make a difference.

Gaining a perspective today on whether the work of the PSC delivered a better public sector over time, as politically promised, requires attention. The setting up of commissions of enquiry to investigate corruption indicates that the ideals of a developmental state, working in the interests of its citizens, was unsuccessful. Therefore, although the PSC sought to advance good governance through its oversight work, it was not able to effect transformational change in the country. The evaluation interventions may have initiated a type of thinking and discourse based on its products, but sustaining momentum was not possible given various political and administrative leadership changes. This has been the experience of many countries around the world that have built M&E capacities only to find them being marginalized based on political appetite for candid performance results.

The Independent Evaluation Office of the United Nations Development Program: Some Strategic Choices

This case study draws from the work that resulted in the transformation of the Evaluation Office of UNDP into the Independent Evaluation Office (IEO). In this case, evaluation successfully influenced country program design toward progressive developmental agendas. This resulted in several international presentations and a UN course drawing on the experience at the International Program for Development Evaluation Training (IPDET).

This second case study reflects on my managerial and leadership experience as director of the Independent Evaluation Office of the UNDP over an 8-year period. In this context, evaluation approaches and interventions sought to advance the notion of transformation. The movement to greater evaluation coverage created a global audience for our work, thus expanding reflection on results and making the organization more evidence based. The promotion of evaluation conversations or dialogues is better than the classic, formalistic approach to evaluation, which can be transactional (working on reacting, responses, and rebuttals in formal settings). This mode does not build collective responsibility for results and may impede organizational learning. The revised approaches included advancing the support element of evaluation, with the National Evaluation Capacity (NEC) series becoming the largest global event by national authority participation. Where stronger national evaluation capacity exists across countries, the receptiveness to evaluation becomes better with an evaluation culture always supportive of advancing discussions on development transformation. Pitching evaluation as a support for the SDGs provided added legitimacy for evaluation, and brought evaluation directly into the discussions on development. It helped integrate the ideals of the UN and imperatives of the SDGs with the priorities, aspirations, and development plans of countries.

Learning from Both Managerial Roles

In both case studies, the thrust has been that evaluation serves a reform and transformation agenda, promoting transparency and generating dialogues across the tiers and levels of functions, bringing in voices and illustrating the discrepancy between intent and outputs and outcomes. Evaluation’s very nature of challenging vision feeds more into the mission of the institutions, supporting assessment of how this varies among practices. In the case of the PSC, the notion of good governance was measured by assessing and reporting on service delivery. In the case of the UNDP, the agency interventions were assessed and reported to both governing boards and countries. The practice of reflection on results is transformative, and can advance the mandate of organizations within which independent evaluation occurs.

Ensuring evaluation coverage is impactful; in the case of the PSC, the organization spanned the entire public sector with more than 140 departments across nine provinces at the national and provincial tiers of government. The impact for potential transformation increases when evaluation engages a full breadth of governance indicators. Monitoring and evaluating the nine values and principles for public administration against performance indicators allowed for rating and comparison of performance and helped legislatures and parliament hold administrators to account. The success of these measures, however, is still dependent on political will and action on results, which has not been adequately evident from the overall performance of the public sector.

At UNDP, evaluation coverage was also a key feature for increasing the evaluation critical mass. The five-fold increase in evaluation coverage that resulted from a new policy and new approaches beginning in 2013 meant that all of the 130 country programs were assessed and the results presented for action. This increased the basis for meta-synthesis and created more timely opportunities for program revision. Program countries in particular appreciated the exercise of increasing coverage and diversifying products, which provided feedback they found important for their prioritization and decision-making. Other changes to ensure consistent quality assurance through a standing evaluation advisory panel helped create a critical mass and important dialogue to assist with advancing transformation development goals. By the time of my departure, the IEO had struck the sweet spot, with the administrator being a major advocate for the function and the board pleased with the outputs and volume of evidence of UNDP performance globally, helping to justify further funding. This can be considered transformational by pushing into the public domain a sizeable portfolio of work demonstrating the development challenges of countries and bringing attention to the SDGs, the vulnerabilities of people and disadvantaged groups, the constraints, (including inherited structural impediments), and value proposition of the organization.

Some Conclusions

Challenge on the Exclusivity of Judgment

In the context of 2021, evaluators face further challenges as they may potentially lose their exclusivity on judgement ability as action research and co-creation modalities gain prominence with artificial intelligence, machine learning, big data, and reliance on streams over studies. The problem is exacerbated by the fact that assessment is difficult in complex situations (Ofir, 2020) and evaluators will encounter challenges in working in a Blue Marble context of high interconnectivity and fewer boundaries (Patton, 2020).

Reflecting on Transformation Drivers

The experiential backdrop above has laid out some reflections. Evaluation is one part of a broader administrative and political system, and leadership within this plays a role in affirming or marginalizing the process. In the case of national departments, becoming entrenched can be difficult, especially when political leaders with their own imperatives govern the administrative divide between the heads of department or permanent secretary. Further, interpretation of what constitutes administrative and political success, or even transformation, is often at odds with evidence.

How M&E negotiates this difficult terrain—often pitched toward an authority level beyond the organizational head who may not appreciate the results—requires deft leadership skills. Evaluators in this context need to recognize that their work is but one of many streams of information that decision makers receive, consider, and eventually prioritize. The matter of independence, credibility, and use was a theme of the 2013 NEC Conference that brought this matter to the fore from the experiences of government, showing evaluation’s potential and its constraining parameters. The claim of being transformational in such a context is difficult. Evaluation transforming relationships was the theme of the 2011 NEC conference, which addressed evidence-based policymaking and generated multiple publications. From the evaluator perspective, these indicate the desire for causality between outputs and change and implicit acceptance that evaluation is transformational. In reality, transformation is more complex in practice and measuring such instrumentalism is a difficult task.

The Enabling Environment for Transformation

Apart from an enabling environment to assist with transformation, certain interventions provide the platform from which transformative actions can occur. Evaluators have a tendency to focus more on the output and product rather than the related journey toward this goal. Evaluation quality is as much about the process to arrive at the product as it is about the product itself. A conducive environment for enabling transformation through evaluation will include the following elements.

Political Will and Leadership Support

The signals from the political environment are critical to open the space for evaluative conversations. Policies on their own are insufficient and evaluation or accountability advocates are important. Countries such as South Africa, which has explicitly within its constitution bodies to advance democracy and accountability, have an advantage. However, the extent to which the political masters support such institutions in the form of who they appoint, how they fund the function, and whether they take findings seriously or not is critical. On its own, evaluation policies are insufficient to create the enabling environment, and aspects such as a free press, civil society participation, and activism to hold political and administrative leaders to account are needed to bolster the evaluation function.

Evaluation capacity, including dedicated evaluation units and systems that advance a results culture, is also important. In the international system, the evaluation offices of the UN, bilaterals, and international financial institutions (IFIs) that have dedicated evaluation functions can play a role in advancing the mandate of particular agencies through promoting a results culture. The work that these offices undertake jointly with other agencies and the promotion of national or sector-specific evaluation capacity building helps create space for reflecting on results, of government and of the agencies themselves. The cumulative effect of this is helpful for advancing transformation, especially of agencies that have a normative agenda, such as gender.

The Post-Normal or COVID-19 Era

All of the UN response and recovery plans have used evidence to improve research and oversight collaboration. However, the gap remains and few functional systems feed information back to governments, partners, and citizens on the results of the various policy interventions. This means that the plans remain largely aspirational, serving a purpose of resource mobilization, but may not provide evidence of impact given the lack of M&E systems. All of the plans purport to assist the poor and marginalized, address structural and other inequalities, and build a more environmental and economically sustainable future—in essence, be transformative—but evidence of transformation cannot be known without system-wide approaches to assess the changes and report in them independently.

In this chapter, I have suggested that much relativism is present in dealing with the concept of transformation. All evaluative activity is important, and one should use caution in privileging one form over another. This becomes more important in the context of action research, where many voices and streams of information inform a more democratic and broad-based decision-making architecture. Evaluators need to move beyond only understanding and applying methods; they must recognize context and its complexity in assessment, and work with rather than apart from key players. This will enable them to enter the debate and prove value in a rapidly shifting environment that requires comprehensiveness and ability to work across sectors in a multidimensional manner. This shift certainly means that evaluators need to establish how they can be most helpful, working in teams and coalitions that are multidisciplinary and cross-cutting and working alongside a range of technological applications that support access to beneficiary voices. The ability of the profession to navigate this challenging period will alter evaluator identity and the purpose of evaluation, depending on the success of the transition.

References

Barbier, E. B., & Burgess, J. C. (2020). Sustainability and development after COVID-19. World Development, 135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105082

Feinstein, O. (2017). Trends in development evaluation and implications for knowledge management. Knowledge Management for Development Journal, 13(1), 31–38.

Feinstein, O. (2019). Dynamic evaluation for transformational change. In R. D. van den Berg, C. Magro, & S. S. Mulder (Eds.), Evaluation for transformational change: Opportunities and challenges for the sustainable development goals (pp. 17–31). IDEAS.

Feinstein, O. (2020). Development and radical uncertainty. Development in Practice, 30(8), 1105–1113. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2020.1763258

Guterres, A. (2020). A time to save the sick and rescue the planet. New York Times, April 28. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/28/opinion/coronavirus-climate-antonio-guterres.html

Mohammed, A. J. (2019, October 20–24). Opening remarks by the United Nations deputy secretary general. National Evaluation Capacity Conference, Hurghada, Egypt. http://web.undp.org/evaluation/nec/nec2019_proceedings.shtml

Naidoo, I. (1997). The M&E of the Department of Land Affairs, South African Government. In A. de Villiers & W. Critchley (Eds.), Rural land reform issues in southern Africa (pp. 11–14). University of the North Press.

Naidoo, I. (2004). The emergence and importance of monitoring and evaluation in the public service. Public Service Commission News, November/December 8–11. http://www.psc.gov.za/documents/pubs/newsletter/2004/psc_news_book_nov_2004.pdf

Naidoo, I. (2010). M&E in South Africa. Many purposes, multiple systems. In M. Segone (Ed.), From policies to results: Developing capacities for country monitoring and evaluation systems (pp. 303–320). UNICEF. https://www.theoryofchange.org/wp-content/uploads/toco_library/pdf/2010_-_Segone_-_From_Policy_To_Results-UNICEF.pdf

Naidoo, I. (2011, September 12–14). South Africa: The use question – Examples and lessons from the Public Service Commission [conference session]. National Evaluation Capacities Conference, Johannesburg, South Africa. http://web.undp.org/evaluation/documents/directors-desk/papers-presentations/NEC_2011_south_africa_paper.pdf

Naidoo, I. (2012). Management challenges in M&E: Thoughts from South Africa. Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, 25(3), 103–114. https://evaluationcanada.ca/secure/25-3-103.pdf

Naidoo, I. (2019). Audit and evaluation: Working collaboratively to support accountability. Evaluation, 26(2), 177–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389019889079

Naidoo, I., & Soares, A. (2020). Lessons learned from the assessment of UNDPs institutional effectiveness jointly conducted by the IEO and OAI. In M. Barrados & J. Lonsdale (Eds.), Crossover of audit and evaluation practice: Challenges and opportunities (pp. 182–193). Routledge.

Ofir, Z. (2020). Transforming evaluations and COVID-19 [4 blog posts]. https://zendaofir.com/transforming-evaluations-and-covid-19-part-4-accelerating-change-in-practice/

Patton, M. Q. (2018). Principle-focused evaluation: The guide. Sage.

Patton, M. Q. (2019). Expanding furthering foresight through evaluative thinking. World Futures Review, 11(4), 296–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/1946756719862116

Patton, M. Q. (2020, March 23). Evaluation implications of the Coronavirus global health pandemic emergency [blog post]. Blue Marble Evaluation. https://bluemarbleeval.org/latest/evaluation-implications-coronavirus-global-health-pandemic-emergency

Picciotto, R. (2020). From disenchantment to renewal. Evaluation, 26(1), 49–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389019897696

Rist, R. C., & Stame, N. (2006). From studies to streams: Managing evaluative systems. Transaction.

Schwandt, T. (2005). The centrality of practice to evaluation. American Journal of Evaluation, 26(1), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214004273184

Schwandt, T. (2019). Post-normal evaluation? Evaluation, 25(3), 317–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389019855501

United Nations. (2020). COVID-19, inequalities and building back better. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/2020/10/covid-19-inequalities-and-building-back-better/

United Nations Development Programme, Independent Evaluation Office. (2019). Annual report on evaluation 2019. http://web.undp.org/evaluation/annual-report/are-2019.shtml

United Nations Development Programme, Independent Evaluation Office. (2020). Proceedings of the National Evaluation Capacity Conference 2019. http://web.undp.org/evaluation/nec/nec2019_proceedings.shtml

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Naidoo, I.A. (2022). Evaluation for Transformational Change: Learning from Practice. In: Uitto, J.I., Batra, G. (eds) Transformational Change for People and the Planet. Sustainable Development Goals Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78853-7_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78853-7_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-78852-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-78853-7

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)